2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Delphi Classics Ltd

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Delphi Great Composers

- Sprache: Englisch

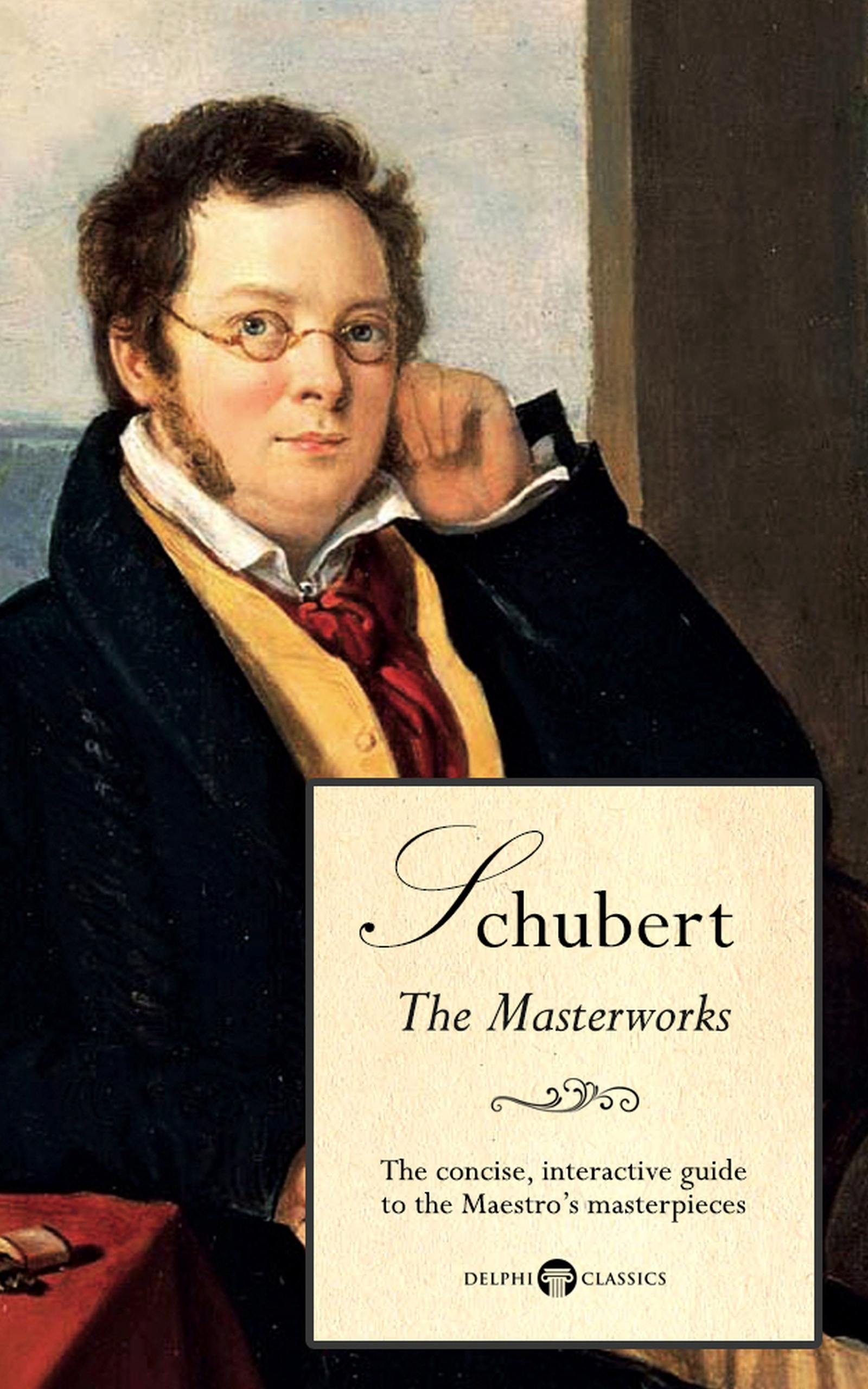

Renowned for melody and harmony, the Austrian composer Franz Schubert represents the foremost bridge between the worlds of Classical and Romantic music. In spite of his short life, Schubert left behind a vast oeuvre of original and inspiring works, including more than 600 secular vocal works, seven complete symphonies, sacred music, operas, incidental music and a large body of piano and chamber music. Although appreciation of his music during his lifetime was limited to a small circle of admirers, his reputation has increased significantly in the decades following his death. Today, Schubert is ranked among the greatest composers of Western music. Delphi’s Great Composers Series offers concise illustrated guides to the life and works of our greatest composers. Analysing the masterworks of each composer, these interactive eBooks include links to popular streaming services, allowing you to listen to the pieces of music you are reading about. Evaluating the masterworks of each composer, you will explore the development of their works, tracing how they changed the course of music history. Whether a classical novice or a cultivated connoisseur, this series offers an intriguing overview of the world’s most famous and iconic compositions. This volume presents Schubert’s masterworks in succinct detail, with informative introductions, accompanying illustrations and bonus texts. (Version 1)

* Concise and informative overview of Schubert’s masterworks

* Learn about the classical pieces that made Schubert a celebrated composer

* Links to popular streaming services (free and paid), allowing you to listen to the masterpieces you’re reading about

* Features a special ‘Complete Compositions’ section, with an index of Schubert’s complete works and links to popular streaming services

* Includes links to rare compositions

* Also features five biographies — explore Schubert's intriguing musical and personal life

Please visit www.delphiclassics.com to browse through our range of exciting eBooks

CONTENTS:

The Masterworks

Symphony No. 1 in D major, D 82

Symphony No. 3 in D major, D 200

Symphony No. 5 in B-Flat Major, D 485

Three Marches Militaires, Op.51, D 733

Mass No. 5 in A-flat major, D 678

Piano Quintet in A major, D 667; “Trout Quintet”

Symphony No. 8 in B Minor, D 759; “Unfinished”

Fantasie in C major, D 760; “Wanderer Fantasy”

Rosamunde, D 797

String Quartet No. 14 in D Minor, D 810, “Death and the Maiden”

Symphony No. 9 in C major, D 944

4 Impromptus, Op.90, D 899

6 Moments musicaux, Op.94, D 780

String Quintet in C major, D 956

Fantasia in F minor, D 940

Winterreise, D 911

Complete Compositions

Index of Schubert’s Compositions

The Biographies

Schubert, Schumann and Franz by George T. Ferris

Franz Schubert by Daniel Gregory Mason

Schubert by Francis Jameson Rowbotham

Franz Schubert by William Henry Hadow

Franz Schubert by Harriette Brower

Please visit www.delphiclassics.com to learn more about our wide range of exciting titles

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 357

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Franz Schubert

(1797-1828)

Contents

The Masterworks

Symphony No. 1 in D major, D 82

Symphony No. 3 in D major, D 200

Symphony No. 5 in B-Flat Major, D 485

Three Marches Militaires, Op.51, D 733

Mass No. 5 in A-flat major, D 678

Piano Quintet in A major, D 667, “Trout Quintet”

Symphony No. 8 in B Minor, D 759, “Unfinished”

Fantasie in C major, D 760; “Wanderer Fantasy”

Rosamunde, D 797

String Quartet No. 14 in D Minor, D 810, “Death and the Maiden”

Symphony No. 9 in C major, D 944

4 Impromptus, Op.90, D 899

6 Moments musicaux, Op.94, D 780

String Quintet in C major, D 956

Fantasia in F minor, D 940

Winterreise, D 911

Complete Compositions

Index of Schubert’s Compositions

The Biographies

Schubert, Schumann and Franz by George T. Ferris

Franz Schubert by Daniel Gregory Mason

Schubert by Francis Jameson Rowbotham

Franz Schubert by William Henry Hadow

Franz Schubert by Harriette Brower

The Delphi Classics Catalogue

© Delphi Classics 2019

Version 1

Delphi Great Composers

Franz Schubert

By Delphi Classics, 2019

COPYRIGHT

Delphi Great Composers - Franz Schubert

First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by Delphi Classics.

© Delphi Classics, 2019.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78877 949 4

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: [email protected]

www.delphiclassics.com

The Masterworks

Franz Schubert was born in Himmelpfortgrund (now a part of Alsergrund, a district of Vienna), Austria on 31 January 1797.

The house in which the composer was born, Nußdorfer Straße 54

The Masterworks: A Short Guide

In this section of the eBook there are concise introductions for Franz Schubert’s most celebrated works. Interactive links to popular streaming services are provided at the beginning and end of each introduction, allowing you to listen to the music you are reading about. The text is also accompanied with contextual images to supplement your reading and listening.

There are various options for streaming music, with most paid services charged competitively at the same rate and usually offering a similar range of albums. Various streaming services offer a free trial (GooglePlay Music, Amazon Music Unlimitedand Apple Music) and Spotify offers a free service after you watch a short advertisement. Amazon Prime members can also enjoy a wide range of free content from Amazon Prime Music. If you do not wish to subscribe to a streaming service, we have included YouTube links for free videos of the classical pieces. Another free option is MUSOPEN, a non-profit organisation that provides recordings, sheet music and textbooks to the public for free, without copyright restrictions.

Please note: different eReading devices serve hyperlinks in different ways, which means we cannot always link you directly to your chosen service. However, the links are intended to take you to the best option available for the piece of music you are reading about.

High-resolution scores for the music would be too large in size to include in an eBook; however, we have provided links to free scores available at IMSLP, the International Music Score Library Project, which can be accessed from the SCORES links in each chapter.

Now, settle back and relax as you immerse yourself in the music and life of Schubert...

Symphony No. 1 in D major, D 82

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

Franz Schubert was born in Himmelpfortgrund on 31 January 1797 as the twelfth child of Franz Theodor Florian Schubert (1763–1830) and Maria Elisabeth Katharina Vietz (1756–1812). His father was the son of a Moravian peasant and had risen in status as a successful parish schoolmaster, operating his own school in Lichtental (Vienna’s ninth district), with numerous students in attendance. The great composer’s mother was the daughter of a Silesian master locksmith and had been a housemaid for a Viennese family prior to her marriage. The family home was not without its share of tragedies. Of their fourteen children, nine died in infancy.

A precocious musician from the very beginning, Schubert received regular instruction from his father at the age of five and a year later he was enrolled at his father’s school. Although it remains disputed in what manner Schubert received his first musical instruction, we do know that he was given piano lessons by his brother Ignaz. However, these lessons did not last long, as within a few months Schubert had excelled his teacher. Ignaz later recalled:

“I was amazed when Franz told me, a few months after we began, that he had no need of any further instruction from me, and that for the future he would make his own way. And in truth his progress in a short period was so great that I was forced to acknowledge in him a master who had completely distanced and out stripped me, and whom I despaired of overtaking.”

Schubert received his first violin lessons from his father when he was eight years old and it was not long until he could play duets proficiently. It was at this time that his father realised that his talented son required more extensive tuition from outside of the family. Schubert was given lessons from Michael Holzer, the organist and choirmaster of the local parish church in Lichtental. Holzer often declared to the boy’s father, with tears in his eyes, that he had never had such a gifted pupil. Indeed, the lessons largely consisted of conversations and expressions of admiration. Holzer gave Schubert instruction in piano and organ, as well as lessons in figured bass — a form of musical notation in which numerals and symbols indicate intervals, chords and non-chord tones for playing the piano, harpsichord, organ and lute.

In 1804 the seven-year-old Schubert came to the attention of Antonio Salieri, Vienna’s leading musical authority since the early days of Mozart. Schubert’s extraordinary vocal talent was recognised and in November 1808, he became a pupil at the Imperial Seminary through winning a choir scholarship. At the Seminary, Schubert was introduced to Mozart’s overtures and symphonies, the symphonies of Joseph Haydn and his younger brother Michael Haydn, and the overtures and symphonies of Beethoven, a composer for whom he would develop a life-long admiration.

The young Schubert’s exposure to the masterpieces of the world’s greatest composers helped lay the foundations of an excellent musical education, combined with visits to the opera and concerts. During his time at the Seminary, Schubert formed a lasting friendship with Joseph Ritter von Spaun (1788-1865), a wealthy Austrian nobleman with high connections. Schubert was eight years younger than Spaun, who supported his friend financially, enabling the aspiring composer to attend the opera and theatre. Spaun also furnished Schubert with much of his manuscript paper. The patronage would last until Schubert’s death, as Spaun hosted the very last Schubertiade on 28 January 1828.

The early 1810’s was a trying period for Schubert, as his mother died suddenly in 1812, leaving the family household in disarray. Nevertheless, he continued in his musical studies undaunted. At the seminary Schubert’s genius emerged through his early compositions, so much so that Salieri himself decided to train him privately in music theory and composition. The youth’s first composition for piano was a Fantasy for four hands,whilehis first song, Klagegesang der Hagar was written the following year. Nothing, it would seem, could daunt the ambitious young composer. He was even permitted to lead the Stadtkonvikt’s orchestra — the first orchestra he would write for. Meanwhile, Schubert devoted the majority of his time at the Seminary to composing chamber music, piano pieces and liturgical choral works. By 1813, he had advanced so much that he felt ready to emulate his great hero Beethoven by writing his own first symphony.

Composed when he was just 16 years old, Symphony No. 1 in D major, D 82 stands as an impressive piece of orchestral music, belying its relative size. The symphony is scored for one flute, two oboes, two clarinets in A, two bassoons, two horns in D, two trumpets in D, timpani and strings. The orchestration, equally balanced between strings and winds, renders it as a suitable piece for both small chamber orchestras and larger ensembles. As found in many of Schubert’s early works, the trumpets are scored particularly high, perhaps signalling a touch of youthful bravado. The symphony comprises four movements and typically last a little under 30 minutes:

Adagio - Allegro vivace

Andante in G major

Menuetto. Allegro

Allegro vivace

A legend survives that tells how the symphony was first performed by the orchestra of the Seminary as a leaving present in honour of the director, Innocenz Lang. From the opening bars, it reveals the influence of Mozart’s late and Beethoven’s early symphonies. After the example of Joseph Haydn, the first movement features a slow introduction, followed by an Allegro vivace (very fast) in the customary tripartite form, reminiscent of Haydn’s Symphony No. 104 in D major (H. 1/104). The exposition — the initial presentation of the thematic material of a musical composition — provides two contrasted subjects, while the central development ends with a return of the theme from the introduction. Beethoven’s influence is most keenly felt in the melodic material of the movement, while the occasional textures and turns of phrase recall Mozart’s style.

The second movement, the G major Andante (moderately slow), opens with gently lilting strings, though the mood shifts in the second section, causing a surprise for the listener. The key of the first movement, allegro (fast and bright), is reprised in the third movement for the Minuet, which is structured as a scherzo rather than a dance, with a contrasting Trio in the style of a Ländler (a folk dance in 3/4 time that was popular in Austria). In the final movement, the first violins introduce the principal theme, as well as the more lyrical second subject. The movement is prominent for how Schubert pushes the trumpet players up to a high D6 in a repeated fashion, calling for multiple doublings between horns and trumpets.

Symphony No. 1 in D major is a surprisingly developed piece of music, representing a work of clear optimism, adequately marking the close of the composer’s school career, with promising signs of his future masterpieces.

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

A reputed portrait of Schubert at the age of 16, when he composed his first symphony

The first page of the score

The first violin’s opening bars

Portrait of Salieri by Joseph Willibrord Mähler, 1815

Joseph Ritter von Spaun, c. 1859. Spaun was an Austrian nobleman, who is best known for his friendship with Schubert.

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler, 1820. Beethoven was Schubert’s lifelong hero and would exact a lasting influence on his life’s work.

Symphony No. 3 in D major, D 200

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

Schubert left the Seminary at the end of 1813, returning home to receive his teacher training at his father’s school, St Anna Normal-hauptschule. In spite of his undoubted talents as a musician and composer, Schubert’s father feared that his son would be unable to earn a living through his music and that a career as a school teacher would provide him the security of a stable wage. Schubert entered the school as teacher of the youngest pupils and for over two years he endured a monotonous time, far from the dazzling hopes he had entertained in his final year at the Seminary. Nonetheless, there were compensatory interests at this difficult time. He continued to take private lessons in composition from Salieri, who provided a more detailed technical training than any of his other teachers.

It was not long until Schubert had fallen in love. The young lady was a soprano named Therese Grob, the daughter of a local silk manufacturer. Therese sang in the Lichtental parish church, which Schubert had been attending since he was a child. For the church’s centenary celebrations, Schubert completed his first mass in late July 1814 — the Mass in F, D 105 — and Therese sang the soprano solo at the premiere performance, which Schubert conducted himself. He wanted to marry Therese, but was prevented from doing so due to the harsh marriage-consent law of 1815, which required a bridegroom to demonstrate he had the means to support a family. In November 1816, he attempted to win a musical post in Laibach, in order to support his proposed marriage, but this plan failed too. Alas, the marriage was never to be and on in 1820 Therese married a baker named Johann Bergmann; together they had four children. Schubert himself never married.

1815 was one of the young composer’s most prolific years, when it is estimated he wrote over 20,000 bars of music, more than half of which were for orchestra, including nine church works, a symphony and nearly 150 Lieder. He was still living with his father at home, while teaching at the school and providing private musical instruction, earning enough money for his basic needs, though with little left over for luxuries. His close companion Spaun was well aware that Schubert was discontented with his life at the school and feared for his intellectual development. It is believed that Schubert suffered from cyclothymia throughout his life, partly due to the depression he experienced working as a schoolteacher for his father. In May 1816, Spaun moved from his apartment in the centre of Vienna to a house in the Landstraße suburb. After settling into his new home, he invited Schubert to spend a few days with him. This was most likely Schubert’s first visit away from home or school, offering a rich source of excitement and diversion.

Composed a few months after Schubert’s eighteenth birthday, Symphony No. 3 in D major, D 200 was written between 24 May and 19 July 1815. Like the other early symphonies, it was never published during his lifetime, appearing instead many years later in the first Schubert complete works edition of 1884. Scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, timpani and strings, the symphony is arranged in four movements and typically lasts 23 minutes:

Adagio maestoso – Allegro con brio

Allegretto in G major

Menuetto. Vivace

Presto vivace

One of the composer’s most instantly recognisable and melodic pieces, the first movement opens with a broad introduction reminiscent of the French Overture (a musical form widely used in the Baroque period) in two parts, the first slow and dramatic, the second more lyrical. Then follows the Allegro con brio (fast tempo with brilliance), noted for its charm and the interplay of solo clarinet with syncopated strings, revealing how Schubert’s style had developed from the chamber music to the larger sphere of the symphonic form. It is an extremely dramatic movement in sonata form and its overture-like structure reveals the influence of Rossini, whose music was popular at the time. The long-sustained octaves in the introduction also recall the style of Haydn, as the music gradually shifts to harmonies that migrate into a sullen D minor. After the slow introduction, the Allegro con brio prepares the way for a clarinet that announces the first subject, while an oboe takes the second, joined by a bassoon, before the intervening transition replicates the theme of the introduction.

The second movement is a delightful Allegretto (fairly brisk) in ternary form, evoking a mood of grace and humour, imitating a peasant’s dance, as its rhythms merge into the subsidiary melody. The sprightly Minuet of the third movement is noted for its accented up-beats, giving the impression of a scherzo (a vigorous, light, or playful composition), before being contrasted by a charming Ländler-like trio.

The final movement, marked Presto (quick tempo), is written in sonata form, featuring a tarantella (a rapid whirling dance from southern Italy) rhythm, with bold harmonic progressions and dynamic contrasts to entertain the listener. Once again the resemblance to Rossini’s compositional style is evident in Schubert’s use of rhythm, dynamics and the harmonic relationships between the varying sections. The movement culminates with a brave display of energy, serving in many ways as an opera buffa ensemble conclusion.

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

The site of Schubert’s father’s school, St Anna Normal-hauptschule in 1886

Schubert’s first love, Therese Grob, a soprano singer, painted by her cousin Heinrich Hollpein, c. 1830

Gioachino Rossini as a young man, c. 1815. Rossini (1792-1868) was an Italian composer that gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote many songs, some chamber music and piano pieces and popular sacred music.

The first page of the score

Symphony No. 5 in B-Flat Major, D 485

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

Schubert’s despondency working as a teacher increased and in 1816 he applied for the post of kapellmeister at Laibach, only to be disappointed again with another rejection. His frustration at being unable to live on his musical talents was at no time greater, when a new friend made an opportune offer that would provide him a much needed respite from his daily toils. Franz Schober, a philosophy student and poet, who came of good family and enjoyed ample means, invited Schubert to room with him at his mother’s house. Dashing at the opportunity, Schubert took the brave step of resigning his teaching duties at his father’s school, dedicating his life’s work to music. By the end of the year, he was a guest in Schober’s lodgings.

Schubert sought to increase the household resources by giving music lessons, though these were soon abandoned, as he devoted himself to composition. In a surviving letter, he announces: “I compose every morning, and when one piece is done, I begin another.” He focused principally on orchestral and choral works, although he continued to produce Lieder. The majority of his work remained unpublished, yet manuscripts and copies circulated among friends and admirers, as his name as a young composer of extraordinary talents and virtuosity gradually filtered through the music-loving city.

One of the jewels of this time of great productivity is Symphony No. 5 in B-Flat Major, D 485 — an especially melodic and distinctive piece of music making. The symphony was performed in October, only a month after its composition, at the house of Otto Hatwig, a violinist friend that was a member of the Burgtheater orchestra. Along with Hatwig and his friends, Schubert played viola in an amateur orchestra that was small enough to fit in an apartment. It was at one of the eclectic ensemble’s meetings that Symphony No. 5 was first performed. The piece resounds with the harmonious magic of Mozart, whom Schubert described as “the immortal” in his diary. Schubert was reportedly infatuated with the Austrian composer at the time, exclaiming, “O Mozart! immortal Mozart! what countless impressions of a brighter, better life hast thou stamped upon our souls!” Though Mozart had died over 25 years ago, his music was as popular as ever and for an aspiring composer like Schubert, Mozart’s symphonies were the models to emulate.

Schubert’s Symphony No. 5 is noted for its particularly light instrumentation, in keeping with the spirit of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550 (sometimes referred to as the “Great G minor symphony”). The pieceemploys the smallest orchestra of all Schubert’s symphonies and it is the only one not to include clarinets, trumpets or timpani. Arranged in four movements, it is scored for flute, pairs of oboes, bassoons, horns and strings:

Allegro

Andante con moto

Menuetto. Allegro molto

Allegro vivace

Also in contrast to his previous symphonies, Schubert chose not to open the piece with a slow introduction. Instead he employs a four-bar structural upbeat section, before the main theme starts on the fifth bar. This provides a charming melodic theme, instantly recognisable from its widespread use in various forms of media over the last 100 years. The theme is eventually interrupted as the movement experiments with stranger keys. Eventually, there is a recapitulation of the first theme in the key of E flat, followed by the restoration of original key of the movement.

The slow movement opens with a theme in two repeated stanzas, before a modulation to C flat, which is characteristic of Schubert’s compositions. Then there is a return to the main theme, passing through G minor. The third movement is reminiscent of Mozart’s Menuetto for Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K. 550 in terms of chromaticism — when composers intersperse the primary diatonic pitches and chords with other pitches of the chromatic scale. The piece only gradually introduces instruments, beginning with the bassoon and strings, giving the subtle suggestion of a pastoral mood. The final movement, marked Allegro vivace, is the shortest of the four movements. It opens with a characteristically cheerful tune, which soon gives way to numerous harmonic surprises and developments.

This remarkable work of youthful ingenuity showcases Schubert’s early mastery of symphonic writing, manifesting a piece that is full of youthful exuberance and bursting with appealing tunes. Incidentally at this time, Schubert had commenced his studies for a law degree. Thankfully for us, his work on this symphony was enough to convince him to give up one path to follow another.

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

The first page of the score

Franz von Schober (1796-1882) was an Austrian poet, librettist, lithographer, actor in Breslau and Legationsrat in Weimar. Schober wrote lyric poetry and in 1821 the libretto for Schubert’s opera ‘Alfonso und Estrella’, as well as several other vocal pieces.

An 1821 drawing of Schubert by Josef Kupelwieser

Mozart wearing the badge of the Order of the Golden Spur that he received in 1770 from Pope Clement XIV in Rome. The painting is a 1777 copy of a work now lost.

Three Marches Militaires, Op.51, D 733

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

In the summer of 1818 Schubert found employment as a music teacher to the family of Count Johann Karl Esterházy at their château in Zseliz, in modern-day Slovakia. The pay was relatively good and his duties teaching piano and singing to the Count’s daughters — the sixteen-year-old, Marie and her twelve-year-old sister, Caroline — were relatively light, allowing him the freedom to compose. It is believed that he wrote his celebrated Marche Militaire in D major for the Count’s two daughters, in addition to several other piano duets. One of Schubert’s most memorable melodies appears as the first of the three marches in the collection The Three Marches Militaires, Op.51, D 733. All three pieces were written for piano four-hands and published eight years later in Vienna by Anton Diabelli.

Widely known as “Schubert’s Marche militaire”, March No. 1 in D major is composedin ternary form, with a central trio leading to a reprise of the main march. Certainly among Schubert’s finest works of the period, itevokes a cheerful mood of strength and vivacity, which despite its lack of technical difficulty, is a surprisingly mature piece of music. It adequately epitomises the composer’s buoyant spirits, now that he had escaped the drudgery of a life as a school teacher and was finally enabled to pursue the career of a composer.

The march was written for the concert-hall rather than the military parade and it has enjoyed a long history of critical approval, proving its worth as a piece of influential prowess. March No. 1 in D major has been arranged for full orchestra, military bands and many different combinations of instruments. It has been quoted in numerous other works, notably Franz Liszt’s paraphrase Grand paraphrase de concert and Stravinsky’s Circus Polka. It later achieved prominence in Walt Disney’s animated short Santa’s Workshop. In advertising, the march was used as the theme music by the Autolite company to promote its products, especially in a 1940 promotional film produced by the Jam Handy organisation, famous for its closing sequence, featuring stop motion animation of the products marching past Autolite factories.

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

The first page of the score

Schubert House or Owl Chateau, where Schubert lived during his time serving Count Johann Karl Esterházy and where he likely composed his Three Marches.

Schubert as a young man

Mass No. 5 in A-flat major, D 678

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

In 1819 Schubert’s friends were settling into regular employment and marriage and so the composer felt that he too must seek a source of regular employment. There were few options available at the time to an aspiring composer, although the writing of church music was one viable option. His previous sacred compositions had been mostly written for the parish church at Liechtenthal, where Schubert had enjoyed public success in 1814 with his Mass in F major. However, as the decade was drawing to a close, it appears he gave the composition of church music a more professional and ambitious approach.

Schubert began work on Mass in A flat major, D 678 in November 1819, though it would not be completed until 1822 and he would return to revise it in 1826, when he was applying for the position of Court Vice-Kapellmeister. In a surviving letter of 1822, written to his friend Joseph von Spaun, Schubert declares his satisfaction with the mass and refers to a possible dedication to the Emperor or Empress. However, it appears no performance took place, despite the frequent revisions. When he showed the work to Josef Eybler, the Kapellmeister of the Royal Chapel, in 1826, he was told that it was not in the style favoured by the Emperor, who preferred a more conservative sacred work. Nevertheless, today the Mass in A flat major is regarded as one of composer’s most accomplished sacred works and it is evident that Schubert himself must have regarded the piece highly due to his extended revisions of the setting.

The Mass in A flat majorD 678 is classed as a Missa Solemnis (Latin for ‘solemn mass’), a genre of the mass ordinary, festively scored and rendering the Latin text extensively, opposed to the more modest Missa brevis. It is scored for flute, pairs of oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns and trumpets, three trombones, timpani, strings and organ, with four solo voices and choir. The mass consists of six movements and a full performance usually has a duration of 46 minutes:

1, Kyrie, Andante con moto, A-flat major

2, Gloria, Allegro maestoso e vivace, E major, 3/4

Gratias agimus tibi, Andantino, A major, 2/4

Domine Deus, Rex coelestis, A minor

Gratias agimus tibi, Andantino, A major, 2/4

Domine Deus, Agnus Dei, Allegro moderato, E major

3, Credo, Allegro maestoso e vivace, C major

Et incarnatus est, Grave, A-flat major, 3/2

Et resurrexit, Allegro maestoso e vivace, C major

4, Sanctus, Andante, F major, 12/8

Osanna in excelsis, Allegro, F major, 6/8

5, Benedictus, Andante con moto, A-flat major

Osanna in excelsis, Allegro, F major, 6/8

6, Agnus Dei, Adagio, A-flat major, 3/4

Dona nobis pacem, Allegretto, A-flat major

Compared to his four previous masses, the handling of the instruments is noticeably different, employing an idiomatic use of the woodwind. In the first movement, Kyrie, the two upper voices are answered by the tenors and basses, while the Christe eleison is introduced by the solo soprano, followed by the other soloists. The mass adopts a musically interpretive stance to the Latin text, revealing Schubert’s increasing confidence in his technical capabilities and knowledge of harmony. Due to his experience in composing sacred music, he now felt able to add further meaning to the standard text with his own explorative approach. In his previous masses he was known for omitting certain passages from the text to suit his musical needs, but now he takes even greater freedoms in the composition, adding and removing text while deepening expression and enhancing aspects of sacred meaning.

The final Dona nobis pacem is another notable section of the mass. It restores the original key of A flat major and conveys a sacred and hushed conclusion, providing a powerful end to the piece. Although Schubert had worked for three years on Mass No. 5, which would be the last of his settings of the Catholic liturgy, the result is one of the most beautiful settings in musical literature, celebrated for its devotional nature and the balanced brilliance of the composition.

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

The first page of the score

Franz Schubert in a watercolour by Wilhelm August Rieder, c. 1825

Joseph Leopold Eybler (1765-1846) was an Austrian composer and contemporary of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Joseph Ritter von Spaun (1859-1788) was an Austrian nobleman, an Imperial and Royal Councillor, lottery director, and honorary citizen of Vienna and Cieszyn. He is best known today for his friendship and correspondence with Schubert.

Piano Quintet in A major, D 667, “Trout Quintet”

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

A genre that flourished during the nineteenth century, the piano quintet is a work of chamber music written for piano and four other instruments. Among the best known and most frequently performed piano quintets, aside from Schumann’s, is Schubert’s “Trout” Quintet in A major. It was written close to the time of Mass No. 5 in 1819, though it was not published until 1829, a year after the composer’s death. Turning his back on the usual piano quintet arrangement of piano and string quartet, Schubert arranged his Trout Quintet for piano, violin, viola, cello and double bass. The fourth movement is a set of variations on Schubert’s earlier Lied “Die Forelle” (“The Trout”), explaining the piece’s popular sobriquet. The quintet was written for Sylvester Paumgartner, of the city of Steyr in Upper Austria, who was a wealthy patron and amateur cellist. Previously, Paumgartner had convinced Schubert to produce a set of variations on the Lied and he also inspired the composer to write numerous other pieces.

The quintet is arranged in five movements:

Allegro vivace (A major)

Andante (F major)

Scherzo: Presto (A major)

Andantino – Allegretto (D major)

Allegro giusto (A major)

The work is distinctive for employing a rising sextuplet figure from the song’s accompaniment, which acts as a unifying motif throughout the five movements, as related figures appear in four out of the five movements.

Written in sonata form, the first movement’s exposition shifts from tonic to dominant. Schubert’s harmonic language is innovative. After stating the tonic for ten bars, the harmony shifts abruptly into F major in the eleventh bar. The development section opens with a similar abrupt shift, from E major to C major. Harmonic movement is measured at first, though it becomes quicker with the return of the first theme and the harmony modulates in ascending half tones.

The second movement is composed of two symmetrical sections, the second being a transposed version of the first, except for differences of modulation, allowing the movement to end in the same key in which it began. The middle movement also contains mediant tonalities, such as the ending of the first section of the Scherzo proper. The fourth movement provides variations on Schubert’s “Die Forelle”, choosing not to transform the original theme into new thematic material, but instead concentrating on melodic decoration and changes of mood. In each of the first few variations, the main theme is played by different instruments. In the fifth variation, Schubert uses the flat submediant, creating a series of modulations that eventually lead back to the movement’s main key.

The final movement, marked Allegro giusto (strict allegro — neither too fast nor too slow) also features two symmetrical sections. It contains three lengthy, almost identical repeats of the same musical material. Although the movement lacks chromatic ornamentation, its harmonic design is particularly pioneering: the first section ends in D major, the subdominant — contradictory to the aesthetics of the Classical musical style at the time, which usually demanded that the first major harmonic event in a piece should shift from tonic to dominant.

The Trout Quintet is a leisurely work, characterised by lower structural coherence, underlining Schubert’s melodic inventiveness. The movements feature unusually long repetitions of previously stated material, sometimes transposed, with little or no structural reworking, aimed at generating an overall unified dramatic design. Today, it is regarded as an important piece in the history of classical music due to its original harmonic language, which is rich in mediants, chromaticism and timbral characteristics. Unlike the other famous piano quintets of world music, the Trout Quintet boasts a unique sonority in the piano part, which for substantial sections concentrates on the highest register of the instrument, with both hands playing the same melodic line an octave apart. The work would go on to exert a major influence on the later Romantic composers, especially Frédéric Chopin, who admired Schubert’s ingenious approach to piano composition.

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

The Swiss piano quintet, giving an illustration of a typical piano quintet arrangement: sitting Willy Rehberg (piano) and Rigo (viola), standing Louis Rey (first violin), Emile Rey (second violin) and Adolphe Rehberg (cello), c. 1900.

The opening bars of Piano Quintet in A major, D 667

The first page of the score

Frédéric Chopin, daguerreotype by Bisson, c. 1849

Symphony No. 8 in B Minor, D 759, “Unfinished”

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

During the early 1820’s, Schubert was associated with a close-knit circle of artists and students, who liked to host social gatherings known as Schubertiads. Many of these intellectual meetings took place in Ignaz von Sonnleithner’s large apartment in the Gundelhof (Brandstätte 5, Vienna). Schubert, who was only a little more than five feet tall, was nicknamed “Schwammerl” by his friends, translating as “Tubby” or “Little Mushroom”. According to surviving accounts, it seems that he enjoyed a busy social life and occasionally drank to excess. However, his close circle of friends was dealt a blow in 1820, when Schubert and four of his friends were arrested by the police, who in the aftermath of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars were on their guard against revolutionary activities and duly suspicious of student gatherings. One of Schubert’s friends, Johann Senn, was put on trial, imprisoned for a year and then permanently banished from Vienna. The other four captives, including Schubert, were severely reprimanded for “inveighing against officials with insulting and opprobrious language”.

Schubert’s compositions of this period demonstrate a marked advance in development and maturity of style. The unfinished oratorio Lazarus, D 689 was begun in February; later followed by the Wanderer Fantasy in C major for piano, D 760, whileSchubert had two operas staged: Die Zwillingsbrüder and Die Zauberharfe. Although up to this time his larger compositions had been restricted to the amateur orchestra at the Gundelhof, his reputation as an accomplished composer was in the ascendant, winning for him a more prominent position in the wider public. Nonetheless, publishers still remained distant, with Anton Diabelli only hesitantly agreeing to print some of his works on commission. The first seven opus numbers, which were all songs, appeared on these terms.

It was during this particularly fruitful period of his career that Schubert commenced work on the piece that would be later numbered as Symphony No. 8 in B minor, D 759. It was famously left unfinished, being left with only two movements; although the composer would live for another six years, for some reason or another he never found the time to complete it. Still, it is a piece of rare dramatic power and pioneering vision, which has been called by some the first Romantic symphony due to its emphasis on the lyrical impulse within the dramatic structure of a Classical sonata form. Interestingly, its orchestration is not solely structured for functionality, but experiments with combinations of instrumental timbre, foreshadowing the later advances of the Romantic movement. Musicologists still disagree as to why Schubert failed to complete the symphony, with some speculating that he stopped work in the middle of the scherzo in the fall of 1822 as he associated it with his initial outbreak of syphilis, while others have proposed that he was distracted by the inspiration for his Wanderer Fantasy, which occupied his time and energy immediately afterward.

Symphony No. 8 in B Minor, D 759 isscored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani and strings:

Allegro moderato

Andante con moto

The first movement opens in sonata form with softly playing strings, in turn followed by a theme shared by the solo oboe and clarinet. The second subject opens with a well-known lyrical melody, stated first by the cellos and then by the violins to a gentle syncopated accompaniment. This is interrupted by a dramatic closing group alternating heavy tutti sforzandi (playing a note with sudden, strong emphasis) interspersed with pauses and developmental variants of the G major melody, ending the exposition. A remarkable feature of the movement takes place in measure 109, when Schubert holds a tonic B pedal in the second bassoon and first horn under the dominant F-sharp chord, reminiscent of the conclusion of Beethoven’s development in the Eroica Symphony.

Composed in E major, the second movement is marked Andante con moto (slowly, but with motion) and alternates two contrasting themes in sonatina form (sonata form without development, with a quietly dramatic, elegiac, extended coda). The first theme is lyrical in nature and is introduced by the horns, low strings, brass and high strings performing in counterpoint. The second theme is mournful in a minor tone, as four simple unharmonised notes in transition stress the tonic chord of the relative C-sharp minor quietly.

The coda (the passage that brings the piece to an end) later assumes a new theme framed as a simple extension of the two-bar E major cadential figure that opened the movement, before giving way to the laconic triadic first-violin transition motto and a restatement of the first theme by the woodwinds in distant A-flat major. This is followed by the motto once more leading back to the tonic E major for a final extended transformation of the first theme.

Symphony No. 8 in B minor was never played in Schubert’s lifetime, only to be rediscovered 43 years later, when it was given its first performance in Vienna in 1865. Schubert had given the manuscript to his friend Josef Huettenbrenner as a present for his brother Anseim, who later arranged a piano duet version of the movements, which he and his brother played together. For many years the manuscript remained in Anseim Huettenbrenner’s possession, its existence only known to a few, until it finally came to the attention of the conductor Johann Herbeck. After the release of the two completed movements, several music scholars made great endeavours to prove that the piece was indeed complete in its two-movement form. Whether or not this is true, Symphony No. 8 continues to captivate the listening public with its abbreviated structure and today it is widely considered to be one of Schubert’s most cherished works, inspiring many composers to produce their own ‘completions’ for the enigmatic composition.

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

Ignaz von Sonnleithner in 1827 by Josef Eduard Teltscher. Von Sonnleithner (1770-1831) was an Austrian jurist, writer and educator, who also founded the Society of Music Friends of the Austrian Imperial State in 1812.

Brandstätte 5, Vienna, where the famous ‘Schubertiads’ took place

Brandstätte in 1870

The opening page of the original manuscript

The first page of the score

The opening melody of Symphony No. 8 in B Minor, D 759

Third movement, first page, facsimile, 1885, in J. R. von Herbeck’s biography

Fantasie in C major, D 760; “Wanderer Fantasy”

AMAZONAPPLEGOOGLEMUSOPENSPOTIFYYOUTUBESCORES

Popularly known as the ‘Wanderer Fantasy’, Schubert’s Fantasie in C major, D 760 is widely considered the composer’s most technically demanding composition for the piano. Schubert himself is known to have declared that “the devil may play it,” in reference to his own inability to render it correctly. A four-movement fantasy for solo piano, the piece was composed in late 1822, immediately after Schubert ceased work on the Unfinished Symphony. In hope of remuneration, it was dedicated to Carl Emanuel Liebenberg von Zsittin, who had studied piano with Johann Nepomuk Hummel. As well as a technically formidable challenge for the performer, the piece is also a structurally challenging four-movement work that combines theme-and-variations with sonata form. The entire piece is based on a single basic motive from which all themes are developed. This motive is distilled from the theme of the C-sharp minor second movement — in essence a sequence of variations on a melody taken from Schubert’s song Der Wanderer, D 493.

The original lied (German for ‘song’) was composed in October 1816 for voice and piano. The words were sourced from a German poem by Georg Philipp Schmidt. The song commences with a recitative, describing the setting: mountains, a steaming valley and the roaring sea. The wanderer is strolling quietly, unhappily, and asks with a sigh the question: “where?” The following section consists of 8 bars of a slow melody sung in pianissimo, describing the feelings of the wanderer: the sun seems cold, the blossom withered, life is old. The wanderer expresses his conviction of being a stranger everywhere. This 8 bar section was later employed by Schubert as the theme on which the Wanderer Fantasy is based.

The four movements of the fantasy are played without a break, as each transitions into the next instead of ending with a definitive cadence. Each movement opens with a variation of the opening phrase of the lied Der Wanderer. The second movement, marked adagio, states the theme in virtually the same manner as it is presented in the song, whereas the three fast movements provide variants in diminution. The first movement is written in a monothematic sonata form in which the second theme is another variant, the third, “presto,” a scherzo in compound time and the finale presents a quasi-fugue that makes increasing demands on the performer’s technical and interpretive powers as it races on to its conclusion.