Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

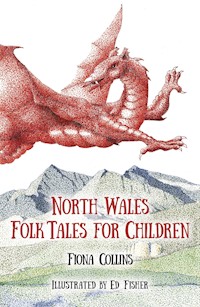

Wales is especially rich in the folklore of place, and this collection brings a new perspective to the history of Denbighshire, the oldest inhabited area of Wales. With hills, valleys, moorland and coast, this varied land has inspired many tales of ancient battles, strange creatures and curious customs. This compilation of stories from the ancient lore of the modern county of Denbighshire includes local legends, folk tales, stories of magic and mystery and tales of ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Discover dragons and devils, ghosts and giants, witches and cunning men, poets, heroes, saints, kings and queens and, of course, Y Tylwyth Teg, The Fair Folk. A speaker of both languages of Wales, the author has collected some unusual material which will be of particular interest to non-Welsh speakers, who will meet these tales for the first time here.With illustrations from local artist Ed Fisher complementing the tales, this volume will be enjoyed by old and young alike. Mae'na groeso cynnes Cymreig yma i bawb. There is a warm Welsh welcome here to all.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 285

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FIONA COLLINS

ILLUSTRATED BY ED FISHER

To my mother – Cymraes i’r carn. And for the next generation, especially Sam, Ellen, Jeroen, Anna, SJ, Peter, Lauren, Matt, Ceri-Rhys, Beth, Hannah, Emma and their Australian cousins

First published in 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

© Fiona Collins, 2011

The right of Fiona Collins, to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 7043 6

MOBI ISBN 978 0 7524 7044 3

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

One

The Smallest Cathedral

Two

The White Stag of Llangar

Three

The Devil’s Picture Book

Four

Ghosts of Bodelwyddan Castle

Five

John Henry

Six

Strange Sightings:

The White Lady of Dyserth

A Corpse Candle at Melin y Wig

Ghost Monks at Rhuddlan

The Gwyllgi at Ruthin

Seven

The Beings of Bodfari

Eight

The Dragon of Denbigh

Nine

Catrin of Berain

Ten

The Phoenix, the Turtle and the Traitor

Eleven

Giant Endeavours:

Jumping Giants

Building Giants

A Flaming Giant

Twelve

The Washer at the Ford

Thirteen

Griffiths the Ghost Hunter

Fourteen

Tegla’s Well

Fifteen

Big Bella

Sixteen

Six and Four are Ten

Seventeen

Foxes or Not?

Eighteen

The Three Tasks

Nineteen

The Speckled Cow

Twenty

Siôn Robert the Harper

Twenty-one

The Sad Tale of Ffowc Owen

Twenty-two

Idris and Huw

Twenty-three

Collen and the King of the Fairies

Twenty-four

The Devil’s Music

Twenty-five

Myfanwy Fechan

Twenty-six

Arthur in Ruthin

Twenty-seven

Queen Corwenna

Twenty-eight

The Sleeping King

Twenty-nine

Owain Glyndr

Thirty

The Hill of Seven Knights:

A Retelling of the Second Branch of the Mabinogion

Notes on the Stories

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I have received a great deal of assistance and support in collecting and preparing the material for this book.

I am grateful for the help, encouragement and advice of my friends and fellow storytellers Cath Aran, Amy Douglas, Andy Harrop-Smith, Anne Johnson, Daniel Morden, June Peters and Joe White.

The following people generously shared personal knowledge, and have really enriched this collection: Sam Bennett, Linda Crossley, Edna Ellis, Aled Lewis Evans, Graham Hindley, Teleri and Nia Jarman, Ian Lebbon, Alison Leyland, Penny Mawdsley, Bob Peters, Chris and Jenny Potter and Ioan Talfryn. Valmai Webb of Carrog shared a wealth of local and personal tales from her hospital bed. Sadly, she died before she could see her stories in print.

I have also been helped by: Hedd ap Emlyn, Community Librarian for Wrexham; Fiona Gale, County Archaeologist for Denbighshire; Geraint Jones, Cadw; Kevin Mason, director at Bodelwyddan Castle Trust; Llangollen Library staff and Denbighshire Tourist Information Centre staff. My grateful thanks to them all. All remaining errors and omissions are my own responsibility.

My thanks also to my partner, Ed Fisher, for the evocative pen and ink drawings that bring the stories and their settings to life. Diolch iti am bopeth.

INTRODUCTION

Hiraeth is the Welsh word for a nostalgic, melancholic longing for home: there is no exact equivalent in English. When asked what drew me to live in Denbighshire I can only answer, ‘Hiraeth’. My mother, who was fiercely proud of being Welsh, came from Llansawel, Briton Ferry, in South Wales, and I was born and brought up in England. Yet somehow I always felt hiraeth for North Wales. As a result, I lived variously and for short periods on Môn, Anglesey, in Gwynedd and in Powys, before finding my home in Sir Ddinbych, Denbighshire, in 2003.

I had no family connections here before meeting my partner Ed, whose fine pen and ink drawings illustrate the stories. He has lived in the same house in the village of Carrog for nearly forty years, during which time alterations to the county boundaries of Wales have changed his address from Sir Feirionnydd, Merionethshire, to Clwyd, and then to Sir Ddinbych, Denbighshire.

Although the present boundaries of the county are relatively new, I have used them to decide, for the purposes of this collection, what counted as a Denbighshire folktale. However, the important thing is that these stories are intimately connected to the land, not to administrative pronouncements that have defined it.

Stories are communicated through language, and Wales’ two languages mean that she is doubly rich in tales and words in which to tell them. English is my mother tongue, and Welsh my second language. There are stories here that I have collected through the medium of Welsh, and with the support and encouragement of Welsh speakers.

I have sometimes been acutely conscious of being an outsider, wondering if I really know my adopted ‘square mile’ well enough to write this book. Life-long and long-term residents of the county have been generous in their help and enthusiasm for the project. I am also aware that, traditionally, the place of the storyteller is outside the community, so that he or she can see, voice and remember what happens on behalf of those who are so busy being and doing that they cannot stand back and observe.

We storytellers respectfully acknowledge the tellers ‘standing behind us’ when we retell an old tale: a long chain of ancestors, wordsmiths, bards and poets, connecting past and present. I can feel the presence of those invisible tellers in all these tales; their tongues have licked the stories into shape over many tellings. My thanks to the tellers who first told these tales, to the early collectors who wrote them down and saved them from being lost, and to the storytellers and writers who continue to share and pass them on, whether to earn a living or just for the sheer pleasure of linking past and present in a circle of words.

Now it’s time for you to play your part, and keep the stories circling. I hope you will enjoy this book, whether the stories you meet here are new or old friends. If you like the stories please pass them on – and when you do, tell them in your own way, not mine. If you have never been to Sir Ddinbych, Denbighshire, perhaps the stories will inspire you to visit. If you are already familiar with this part of Wales, I hope you will feel that you know it in a different and deeper way after reading this book. Maybe it will spur you to search for other folk tales of Denbighshire: there are many more in this green and lovely area of Cymru, Wales.

Fiona Collins, 2011

One

THE SMALLEST CATHEDRAL

This story begins in Scotland, with Glasgow’s patron saint. However, the tale soon travels across the sea to Denbighshire and comes to Britain’s smallest cathedral, which stands near the River Elwy in Llanelwy, St Asaph.

The saint is Cyndeyrn, who lived during the sixth century. He is probably better known outside Wales by the Scottish version of his name, Kentigern, or else as Mungo, the affectionate nickname that his teacher, St Serf, gave to him. He became Bishop of Strathclyde, but political unrest forced him to flee across the sea to Wales, probably in a curragh or sea-going coracle, about the year AD 550. His story was recorded by Josselin of Furness, whose words I sometimes quote in this retelling.

Dewi Sant, the Patron Saint of Wales, welcomed Cyndeyrn warmly to Menevia in Pembrokeshire, and the two holy men spent much time together.

Cyndeyrn felt a call from God to build a monastery in Wales, and set out to find the right place. He followed the Roman Road northwards through Caersws and then across the Berwyn mountains to the southern end of Dyffryn Clwyd, the Vale of Clwyd. As he wandered up the valley with a crowd of disciples, searching for the place to found his settlement, a white boar came out of the forest and first approached him, looking fixedly at Cyndeyrn, and then walked away from him, turning back constantly to see if he were following. Cyndeyrn followed the boar until it reached the banks of a winding river. There it stopped and began to root and delve in the soft earth. Seeing the boar already preparing the ground for the foundations, Cyndeyrn gave thanks to God and declared that he would found his monastery on this spot.

Perhaps Cyndeyrn was influenced not only by the sign or miracle of the boar but also by hiraeth, that untranslatable Welsh word meaning a longing for home. After all, he came from Strathclyde, which, like its Welsh equivalent Dyffryn Clwyd, means the Vale of Clyde or Clwyd. I hope he did feel a little at home in such a beautiful spot. The place he chose was on the southern bank of the River Elwy at its confluence with the Clwyd, in the kingdom of Maelgwyn, King of Gwynedd.

For a time, things were difficult for Cyndeyrn. He incurred King Maelgwyn’s wrath by granting sanctuary to one of the King’s men and refusing to give him up. The King threatened vengeance and interrupted the building work again and again, but at last the monk’s dignified courage won him over and he converted to Christianity. From then on he favoured Cyndeyrn and confirmed him in all his privileges.

Cyndeyrn set his mind on building a monastery in which ‘the scattered sons of God might, for their soul’s health, come together like bees.’ Building work proceeded apace, for the monks were as full of zeal as the bees, and soon the monastery rose. They built it all of wood, ‘in the manner of the Britons, because they were not yet able to build in stone as they did not have that skill.’ The settlement flourished, and the community soon numbered 965 monks, of whom 365 were sufficiently scholarly to form three choirs of over one hundred choristers each, which would continually follow each other to sing in the church, so that it was never without the sound of praises to God.

When the King of Strathclyde had defeated his enemies, he summoned Cyndeyrn to return from exile and convert the pagans in his kingdom. At first it seemed that it would be hard for Cyndeyrn to choose from so many dedicated and devout monks one to lead the monastery in his place. He was quite a hard act to follow, for in his fervent pursuit of sanctity, he slept on a bed of stone with a rock for a pillow. On rising, the first thing he did every day was to strip naked and wade into the centre of the River Elwy, to stand up to his neck for hours in the water until he had sung ‘all the psalms in their entirety’. But a worthy successor was at hand, in the form of his pupil Asaph.

Asaph was the grandson of a sainted King of northern Britain called Pabo Post Prydain, which means Pabo the Pillar of Britain. The legend tells that Pabo renounced his kingdom to become a hermit at Llanabo on Anglesey, where his grave can still be seen. Pabo divided his kingdom in the Old North between his sons when he retired from secular life, and was the grandfather of a trio of saints, Tysilio, Deiniol and Asaph.

Young Asaph was sent to the College of Elwy to be taught by Cyndeyrn, and was soon recognised by everyone there as an exceptional student. This young paragon ‘shone in virtues and wonders from the flower of his earliest puberty. He was diligent to follow the life and teachings of his master.’ What marked Asaph out as a worthy successor to Cyndeyrn, though, was not his application to his studies. Rather, it was a miracle.

One winter morning Cyndeyrn, having sung his psalms, emerged from the freezing waters of the Elwy to dry and dress himself. But he could not get warm, and shivered so much that his followers were afraid that he was going to fall into a fit. Cyndeyrn turned to young Asaph and, his teeth chattering so hard that Asaph could not at first understand what he wanted, asked him to fetch fire from the kitchen, so that he could warm himself.

As soon as he could make out what his master was trying to say, Asaph ran willingly to the kitchen of the monastery and asked for fire. But he had come in such haste that he had not brought anything in which to carry the burning wood back again. The lay-brother in the kitchen, laughing at his lack of preparation, jokingly said, ‘Stretch out your garments if you have the strength to take away these live coals, because I do not have anything at hand in which you may carry them.’

Asaph did not baulk at this, but immediately gathered up his robe and scooped the hot embers into it with his bare hands. Then he turned and dashed back to where Cyndeyrn was waiting, shivering and shaking. He tipped out the embers at his master’s feet, gathered them into a tidy pile with his bare hands and blew on them until they blazed up in a merry conflagration. When Asaph sat back on his heels to look up at his master, Cyndeyrn was staring at him with such a mixture of astonishment and delight on his face that the lad was nonplussed.

‘What is this that you have done, my boy?’ asked Cyndeyrn in wonder.

‘Only brought a little fire to warm you, master,’ whispered Asaph in confusion, ‘I had no brazier to carry it in. I am sorry.’

‘Sorry, lad? Don’t be sorry! Stand up. Let me see your robes. Show me your hands.’

Asaph obediently did as he was told. There were no scorch marks on his clothing, no burn marks on his hands. In fact they were so clean that he, like his teacher, might have stepped out of the scouring waters of the river.

Cyndeyrn knew a miracle when he saw one. From that moment, Asaph was marked out as his successor, and when Cyndeyrn went back to Strathclyde around AD 573, Asaph was installed as the second Bishop.

When Cyndeyrn left, he went out through the north door of the cathedral, which from then on was kept always closed, and ever after the monks showed their reverence for him and their grief at his departure by refraining from using it. ‘Only once a year … was it ever suffered to turn upon its hinges.’ Perhaps this used to happen on his saint’s day, which is variously given as the 13th or 14th January.

I asked the Dean of the cathedral, Chris Potter, if this is why they now use the west door and keep the north door closed, but he explained that he simply prefers the great west door because it gives a finer aspect of the cathedral as one enters. He went on to point out, gently, that it is not really the same door anyway, for the cathedral has been burned and razed to the ground several times: by the English in the thirteenth century, under Edward I, and in the seventeenth century, under Cromwell, and between the two by Owain Glyndwr and the Welsh in 1402.

After Asaph’s death, the church, and later the town, took his name rather than that of Cyndeyrn. Perhaps this was because Cyndeyrn was buried far away in Glasgow, where his shrine still stands in the cathedral named for him. Asaph, however, ended his days on the banks of the Elwy, and was buried in the cathedral. In fact, it was Asaph who elevated the monastery into a cathedral. It may also have been Asaph who moved the cathedral from the river bank to its present site on the top of the hill, but when that happened is not known, for written records were not kept in the early years of the Christian Church in Wales, and much has been forgotten.

The little cathedral soon became a place of pilgrimage, as the faithful came to venerate the memory of a saint who, according to The Red Book of St Asaph, was noted for ‘the sweetness of his conversation, the symmetry, vigour and elegance of his body, the virtues and sanctity of his heart and the manifestation of his miracles.’

It is not only the cathedral and the town that commemorate Asaph’s existence; so too do many beautiful natural places around the River Elwy. As well as the village of Llanasa, on the other side of the county boundary with Flintshire, one can also find Pant Asa (Asaph’s Hollow), Onnen Asa (Asaph’s Oak), and Ffynnon Asa (Asaph’s Well).

It is said that, one time, Asaph urged his horse to a mighty leap from Ffynnon Asa. Horse and rider landed beyond the cathedral in the high street, where a stone with the impression of the horse’s hoof was still being shown to visitors fifty years ago. It sounds like a marvellous leap, especially as Ffynnon Asa is almost six miles away, as proved by the map of North Wales that Chris Potter has on the wall in the Deond, the Dean’s House.

The Dean was scrupulously impartial on the legends of Asaph’s miracles, for he showed me that R.D. Thomas suggests that the legend of the burning coals is based on a mistranslation of the Welsh word tanwydd (firewood), and that all Asaph was doing was bringing fuel to light a fire for Cyndeyrn. But Jenny Potter, the Dean’s wife, said, ‘Surely the message of the legend is in the loving care and kindness that Asaph showed to his teacher.’

I think she is right. But I still like the story.

Two

THE WHITE STAG OF LLANGAR

In lovely Dyffryn Edeyrnion, the Vale of Edeyrnion, just above the place where the River Alwen joins the Dee, stands a little whitewashed church that was built there in medieval times. All Saints’ Church Llangar served the parish of Cynwyd through many years, as the graveyard shows, until a new, larger church was built in the mid-nineteenth century in the fast-growing village of Cynwyd itself, a bare mile upstream along the Dee. Llangar Church then fell into disuse and disrepair until it was restored in the 1970s. The church is now in the care of Cadw: Welsh Historic Monuments. During its restoration, eight layers of wall paintings were discovered, including medieval representations of some of the Seven Deadly Sins and a fearsome eighteenth-century skeletal figure of Death, standing over burial tools and carrying a spear and hourglass, with twin babies visible inside the bony pelvis. The churchyard is crowded with gravestones, many engraved with englynion, a complex Welsh verse form, while two small, unmarked stones indicate the place where over 300 skeletons were re-buried by the local vicar after being exhumed from beneath the church’s earth floor during the restoration. Llangar Church is first mentioned in records as early as 1291, and the site seems ideal for peaceful prayer and meditation; but it was not the first choice of the medieval builders who raised the church. The legend of the church’s founding is still alive in the area.

Building work began, so the tale tells, on a level patch of land further upstream, where the village of Cynwyd now stands, not far from where the river was bridged in 1612.

All day long the workers laboured; digging out the foundations, dressing the great stones, raising the beginnings of the walls of their new and much longed-for church. Pleased with their efforts, they retired at the end of a long day for a well-deserved night’s rest. But when they returned next morning, they found that all their work had been ruined overnight. The tools they had stacked so neatly had been thrown this way and that; the excavated heaps of earth had poured back down into the foundation trenches; the stones stacked and sorted had been hurled to the far corners of the site. Their hearts grew cold within them as they surveyed the chaos.

‘Someone has done this,’ muttered one of the masons in hushed tones. ‘It couldn’t have happened by chance.’

‘Perhaps it was an accident?’ wondered the second, but his voice sounded unsure.

‘Come now, you two. Why should we waver? This is God’s work we’ve undertaken, to raise a new church to His glory. Surely there is nothing we need to fear!’ With these words, the third mason took up a shovel and began to clear the trenches.

His companions watched him for a moment and then, heartened by their fellow’s good cheer, they began to work too. By midday they had made good the damage once more, and by dusk the first course of the wall lay straight and true. Well pleased with their progress, and after making sure that everything was left safe and secure, the masons trudged homewards.

But as they arrived for work the next morning they could see that all was not well. Once again the evidence that confronted them was clear: everything they had done during the day had been undone in the night.

‘There is something more than human at work here,’ trembled the first mason.

‘Something stronger than us,’ agreed the second, his voice full of fear.

‘Stronger than our Lord’s work? Impossible! Come on, boys, let’s to it!’ exhorted the third, dragging out his spade from beneath a tumbled heap of stones and earth, and wielding it with a will. The others stood nervous and unsure, but after a while, seeing that nothing was going awry, they joined him. All three worked hard, and they worked well, and by evening they had remade what had been unmade, and done more besides. But when it was time to leave, they gazed anxiously around. They were unwilling to leave, but equally unwilling to stay in case of meeting some terrible thing that was undoing their work. At last, they turned their backs and walked homewards. But their hearts were heavy and their thoughts full of fear. Rightly so.

On the third morning, once again all they found was damage and destruction.

‘This is more than we can manage,’ said the first.

‘We are facing something beyond our understanding,’ said the second.

‘Then we must needs take advice,’ said the third as stoutly as he could, for he, too, was now concerned lest their work was cursed. His friends looked at him, waiting to hear what he might suggest.

‘We will go to y Dyn Hysbys, the Cunning Man,’ he declared. ‘He will know what we should do. He will tell us if we have offended the Lord … or some other thing.’ His voice faltered at the thought of what that ‘other thing’ might be. But he rallied. Come on then, lads!’

So they set off to the cottage of the Cunning Man. They feared him, but not as much as whatever was interfering with their work. And they knew him for a wise man, with powers beyond those of normal men. Sure enough, when the Cunning Man saw them approaching his door, he knew only too well why they were there.

‘You are building in the wrong place,’ he told them. ‘Though the site seems good to you, it is not a sacred space in the eyes of our Lord. You must search for and hunt a white stag. It will be sent as a sign, to show you where to build the church. You must move to the appointed place. Until you do, all your efforts will be in vain.’

The three masons listened to his words, gave him gifts and thanked him, and then set out to look for a white stag. They ranged up and down the east bank of the Dee, until they came to the place where the River Alwen joins it from the west. There, from a thicket just above the confluence, a magnificent white stag stared impassively at them as they approached. Only at the very last moment did it turn and bound away. They went after it, and the hunt was long and hard, but at last they brought down the beautiful creature.

Perhaps there was a need for its death because, in those times, a blood sacrifice was often required to ensure the strength and solidity of new walls. Or perhaps the white stag, its colour standing for purity and holiness, was a symbol of Christ, who had to die so that the sins of humans might be forgiven.

Whatever the reason, the meeting place of the rivers, where the stag had first been seen, was chosen as the new site for the church. The building work went quickly and easily, and there was no more supernatural interference. The new church was named Llan y carw gwyn, the church of the white stag, and this was shortened over time, first to Llan-garw, and then to Llangar.

Today the church is a place of serenity and peace, where the visitor can sit on a bench in the churchyard and watch the movement of wild flowers and grasses in the surrounding fields, listening to the murmur of the two rivers merging across a gravel bank just below. But new tales are spun about it still, as I found when I took the members of my Welsh class there. We were welcomed to the peaceful church by Mr Geraint Jones, who, after being Corwen’s postman for forty-one years, became keyholder and guide of Llangar Church – working with Rachael Williams, Cadw’s Custodian of both neighbouring Rhug Chapel and Llangar Church. Mr Jones told us the story of the white stag and explained the wall paintings to us in his mother tongue. Later, as I sat on the graveyard wall beside the porch of the little church, he told me more.

The little church, being off the beaten track, receives few visitors. On one occasion, a couple arrived to look round the church. The gentleman explained to Mr Jones that he had an artificial leg, which made it hard for him to climb the uneven stairs up into the gallery, but nonetheless he persevered. The lady remained in the body of the church, talking with Mr Jones. Hardly any time had elapsed when the visitor came down again.

‘You were very quick, dear,’ said his wife. ‘Ah, well, a lady in a long dress came to me and said I was sitting in her seat, so I thought it best to move.’

Needless to say, there was no one else in the church. When the gentleman had gone out into the churchyard his wife confided in Mr Jones: ‘He’s very sensitive, and often sees and hears things that others don’t.’

On another occasion, as Mr Jones arrived to open the church, he distinctly heard a choir singing inside. At first he froze, but then reasoned to himself that, when closing up the day before, he must have forgotten to turn off the CD player on which he plays hymns and folk tunes sung by some of Wales’ justly famous male voice choirs, to add atmosphere to the little church. He relaxed at the thought, and was fumbling for the key in his pocket, when it dawned on him that though the power might still be on, the CD would long since have finished playing. A chill ran down his back, but nonetheless he turned the key in the lock. As he did so, the voices ceased, and all was quiet. He opened the door, calling out in Welsh, ‘Excuse me for interrupting you. It’ll only be for two hours, and then you can continue with the service.’

There was no reply, and when he opened the door, the church was of course empty, but undoubtedly his courtesy was appreciated, for nothing else happened to trouble him all that day.

Three

THEDEVIL’S PICTURE BOOK

Dewi ap Hywel was a popular fellow in and around Rhuddlan, and plenty of young people came along whenever he held a Noson Lawen, or Merry Evening, at his farm, Henafon. However, older and more respectable members of the community shook their heads in disapproval when stories began to circulate about what went on around Dewi’s kitchen table after the songs and sketches had finished.

‘Cards! They play cards! What kind of recreation is that for honest Christian folk?’ asked Mrs Jones T Mawr in disgust.

‘Gambling on card games … there’ll be trouble, mark my words,’ answered her neighbour, Mrs Parri T Gwyn. ‘The pack of cards is not called “the devil’s picture book” for nothing, Mrs Jones. They are on a slippery slope there, mark my words.’

Clicking their tongues and shaking their heads, the two upright ladies went on their way, turning their righteous eyes away from Henafon Lane. And from behind the hedge, out came Dewi and his good friend Geraint, stifling their laughter.

‘Oh, we are doomed, doomed!’ intoned Dewi between snorts of laughter, while Geraint, one hand on his breast, executed a mock slow march, as if following a funeral procession.

When they had finished laughing, Geraint asked, ‘When will the next Merry Evening be then, Dewi bach?’

‘Tomorrow night. There will be quite a crowd, I think. John Jenkin of Dyserth has promised to bring his fiddle, so there will be plenty of dancing.’

‘And after the dancing?’ asked Geraint hopefully.

‘Don’t worry, there will be cards, of course, and a chance for you to lose more money to me,’ laughed Dewi.

‘Or to win it back and double it!’ declared Geraint optimistically.

‘I don’t think that’s very likely, but you can certainly try!’ Dewi clapped his companion on the back and the two friends set off together, laughing and joking, towards Henafon.

Once they had turned the corner into the lane, someone else stepped out from behind the hedge. Tall, dark and striking, he had a neat pointed beard and sleek black hair set off by two small horns, one on each side of his forehead. The gentleman cocked his head to one side, then took a little notebook from the breast of his coat and made a few jottings and calculations, which seemed to give him a great deal of satisfaction. Then he disappeared in a discreet puff of smoke, leaving nothing but a whiff of sulphur, which was soon cleared by the breeze.

That evening and the next day went by slowly for Geraint and all the other young people, who were eager for the fun to begin at Dewi’s. But at last, the sun set and the lads turned up at Henafon dressed in their finery, with bright neckerchiefs poking out of their jacket collars and coins jingling in their pockets. John Jenkin Dyserth played his fiddle, and there was dancing and singing.

But it wasn’t long before the table was put back in the centre of the room, chairs were set around it and packs of cards came out. The girls sighed and went off to sit in the parlour, knowing they would have no further opportunity to make an impression on the lads now that gambling was to begin. The young men formed into parties and settled down to play. But hardly had they begun when there was a tap at the door and a stranger looked in.

‘Excuse me,’ he began in an English accent, ‘I seem to be lost. Could I trouble you for directions to help me on my way? Aha! I see you are at cards. Might I be so bold as to join you? It is a great passion of mine, and I would be pleased to make up a party, for I see you are one short, young sirs.’

This last remark was addressed to Dewi, Geraint and John Jenkin the fiddler, for they were indeed the only trio among the several groups of four spread around the room. They exchanged meaningful glances, eager and ready to fleece this well-heeled fool.

‘Come in, come in, by all means. Everyone is welcome here if they have the money to make a little bet and keep up with the rest of us,’ smiled Dewi, the perfect host.

‘Oh, I think I can manage that,’ said the stranger smoothly, as he sat down.

They eyed up his expensive frock coat, his silver tipped cane, his elegant cravat – though it is doubtful whether any of them knew the correct name for this piece of neckwear. Geraint gave a slight nod to Dewi, as if to say, ‘Yes, we’ll do ourselves proud here.’ And the game began.

However, much to Geraint’s surprise, the elegant stranger did not prove to be such an easy touch after all. He watched the other players like a hawk, kept his own cards close to his chest, and bet lavishly, which they liked, but won consistently, which they did not. One by one the other parties folded their games in order to watch what was going on at Dewi’s end of the table.

Now it was the stranger who grinned – somewhat wolfishly, Dewi thought, noting the sharpness of his small front teeth – as he drew small piles of their hard-earned, swiftly-lost money towards himself.