Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

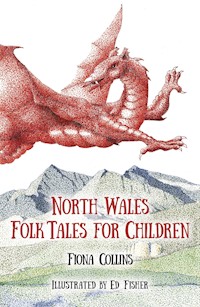

The county borough of Wrexham is rich in folklore, with an abundance of tales to capture the wonders of the Welsh landscape and all its denizens, both real and imaginary: animal, human and even superhuman. This collection, which includes both traditional tales – passed down through generations by word of mouth – and archive material, brings to life the local legends, mysteries and stories of ordinary people doing extraordinary things that make Wales so magical. A speaker of both languages of Wales, the author has collected some unusual material sure to enchant both Welsh and non Welsh speakers. Beautifully illustrated by local artist Ed Fisher, these tales bring to life the ancient wisdom of Wrexham.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 275

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have given me help and inspiration while I have been writing this book. I should like to thank first of all my partner, Ed Fisher, for his beautiful illustrations; Katharine Soutar for the cover picture and Declan Flynn and Ruth Boyes, my editors at The History Press, for their patience and confidence.

My thanks to staff at Wrexham County Borough Library and Information Service; to staff at Wrexham County Borough Museum and Archives, especially Jonathan Gammond and Karen Harris; to staff at the A.N. Palmer Centre for Local Studies and Archives, especially Joy Thomas; to staff of Wrexham Countryside Services, especially Liz Carding and Martin Howarth; to members of the Wrexham Heritage Forum; to members of the Brymbo Heritage Group; to members of Brymbo Local History Group, especially Brian Gresty; to staff and pupils of St Mary’s Aided Primary School, Brymbo, especially Rachel Roberts; to everyone who contributed memories to Wrexham Countryside Services’ Pontcysyllte and Cefn Mawr Community Arts Reminiscence Project; to Siân Owen, who asked me to create a Welsh language story tour around Wrexham County Borough, and to the coach load of intrepid Welsh learners who came on the tour with us; to members of the Glyn Ceiriog branch of Merched y Wawr; to my friend and fellow Welsh learner David Mawdsley for advice on railway matters; to Anne Uruska and Iestyn Daniel for help in finding the poetry of Richard Gwyn; and to my friends and fellow storytellers Michael Dacre, Amy Douglas, Nicola Grove, June Peters, Mike Rust and Dez and Ali Quarrell for their help in finding, shaping (and sometimes pronouncing!) material.

The books and online resources that I have consulted are listed in the bibliography. They have been essential, and I have benefited greatly from the work done by those who have explored this material before me, including Alfred the Great’s biographer, Asser; the Victorian adventurer George Borrow; and Wrexham’s contemporary collector of ghost stories, Richard Holland.

However, it is to the people of Wrexham that I owe my greatest debt, for the stories, poetry and information they have shared with me in the old way, by word of mouth (and sometimes by its modern cousin, email). Most especially I am grateful to Pol Wong, martial artist and Welsh patriot; to Colin Davies and Brian Stapeley of Brymbo; to Deryn Poppitt of Chirk; and to four variously crowned, chaired and eloquent bilingual poets of Wrexham County Borough, who are carrying the flame of an age-old oral and literary tradition: Siôn Aled, Les Barker, Aled Lewis Evans and Peter Jones. This book is dedicated to these four poets, Y Pedwar Bardd.

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Map

BANGOR-ON-DEE

1 The Massacre of the Monks

BROUGHTON

2 Jack Mary Ann

BRYMBO

3 The Twelve Apostles

4 Alice in the Circle: St Mary’s School Ghost

BWLCHGWYNANDROSSETT

5 Fauna and Flora

CAERALYNANDTHEFAIRYMOUND

6 The King of the Giants

CEFNMAWR, MARCHWIEL, ACREFAIR, TREVOR,

GARTHANDFRONCYSYLLTE

7 Wartime Tales

CHIRK

8 The Red Hand of Chirk

9 In the Black Park

COEDPOETH, GRESFORD& RHOSLLANNERCHRUGOG

10 Mining Tales

ERDDIG

11 The Three-Way Crossroad

FRONCYSYLLTE

12 The River that Runs in the Sky

GLYNCEIRIOG

13 A Living Witness

GRESFORD

14 A Wrexham Werewolf

HANMER

15 The Marriage of Owain Glyndwr

HOLT

16 The Boys Beneath the Bridge

LIGHTWOODGREEN

17 Robin Ruin’s Ruin

MAESMAELOR

18 The Old Un o’ the Moor

MARFORD

19 Lady Blackbird

MINERA

20 Dancing with the Fair Folk

OFFA’SDYKE

21 Offa’s Offspring

OVERTON

22 Some Wonders of Overton

PENLEY

23 The Witch of Penley

PENYCAE

24 The Pig of the Valley: John Roberts the Cunning Man

RHOSLLANNERCHRUGOG

25 Buried Alive for Eight Days

RUABON

26 The Red River

WREXHAM

27 One of Six

28 Balaclava Ned

29 Fred and Frances

30 Two Saints

Bibliography

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

The Seven Wonders of Wales

Pistyll Rhaeadr and Wrexham steeple,

Snowdon’s mountain without its people,

Overton yew trees, St Winefride’s well,

Llangollen bridge and Gresford bells.

This little rhyme was written sometime in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, probably by an English visitor to North Wales.

Three of these seven wonders are in Wrexham County Borough in North East Wales, and in this book you will find stories from Wrexham, Overton and Gresford as well as many other parts of this interesting bro, the Welsh word for one’s local district.

The County Borough is a relatively new entity, having been formed in 1996 by uniting parts of Denbighshire and Flintshire with Wrexham Borough. However, the movement of frontiers is nothing new in this borderland part of Wales, and the national boundary with England has been redrawn many times over the centuries. A good example is Offa’s Dyke, the seventh-century creation of a Mercian king, which was probably built as a defensive barrier between Mercia and Wales but now runs right through the middle of Wrexham County Borough. A common description in Welsh for someone who has moved to England is ‘one who has crossed Offa’s Dyke’. However, in Wrexham County Borough one can live to the east of the dyke and still be in Cymru Gymraeg, Welsh-speaking Wales. According to the census of 2011, 12 per cent of the population of Wrexham County Borough consider themselves Welsh speakers, and nearly 21 per cent understand and use some Welsh.

Wrexham itself is the biggest town in North Wales and the seventh largest in the country. Since the beginning of this century, there have been three campaigns to gain city status for Wrexham, but each time it has lost out, most recently to the smaller and quainter new city of St Asaph in neighbouring Denbighshire. However, in 2009, members of Wrexham Council were delighted when UNESCO awarded the status of World Heritage Site, one of only three in Wales, to Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, together with 11 miles of the canal it carries across the Dee Valley, on the grounds that it is ‘a masterpiece of human creative genius’.

The town of Wrexham, or Wrecsam, as it is spelt in Welsh, dates back to at least the eleventh century and has variously been spelt: Writtlesham, Wrechessan, Wrightesham, Wriffam and Gwrecsam. Local poet Siôn Aled told me a shaggy dog story about how it was named after a tavern run by a certain Sam and his wife (gwraig in Welsh), which was known as Ty Wraig Sam (‘Sam’s wife’s house’). However, the Clwyd-Powys Archaeological Trust suggests the Old English personal name ‘Wryhtel’ was combined with ‘hamm’, meaning a water meadow, to give ‘Wryhtel’s river meadow’. This, perhaps on the low-lying ground between the Gwenfro and Clywedog rivers, might have been the original settlement. It must be said that neither Sam nor Wryhtel are Welsh names!

And here is the tension that pulls at the heart of this borderland town. Should it look for its history, or indeed for its future, east towards England or west towards Wales? Roman remains have been unearthed to the west of the town, while Offa put his dyke right though the middle of it, as did Wat, whose earthwork lies parallel to Offa’s Dyke at several points in the borough.

By 1161 there was a Norman castle at de Wristlesham, which has been identified with a motte at Erddig. Holt Castle was built by John de Warenne shortly after 1282, on land granted to him by Edward I, creating one of the Marcher Lordships intended by their new English overlords to keep the Welsh in check.

St Giles’ church was built in 1220, and by Tudor times Wrexham was a prosperous market town. In the industrial era it became the ‘smoky valley’ of collieries, furnaces and clay works, which George Borrow saw as he walked over the border into Wales in 1854. In 1952 Llay Main Colliery was the deepest pit in Britain, and the Miners Welfare Institute there was one of the largest in the country.

Now exhausted land is being reclaimed for housing and industrial estates and Wrexham is re-inventing itself as a tourist destination. Its country parks, historic houses, areas of industrial heritage and places of natural beauty are all worth a visit. So too are its people, who are full of tales, poetry, songs and ready wit.

Wrexham County Borough was the birthplace of two of Wales’ foremost Welsh language poets: John ‘Ceiriog’ Hughes and I.D. Hooson, as well as the influential novelist Islwyn Ffowc Elis. The English language Welsh poet R.S. Thomas was curate in the Wrexham borderlands in the early 1940s at Chirk, where he met and married the artist Mildred Eldridge, and at Tallarn Green, about four miles from Hanmer.

Llŷr Williams, the fine concert pianist, is from Wrexham County Borough and so too are the members of the Fron Choir, or Côr Meibion Froncysyllte, as they were known locally before they hit the big time. Miss World 1961, Rosemarie Frankland, was born in the Wrexham village of Rhosllannerchrugog, a Welsh-speaking enclave which has its own unique dialect words for ‘snow’, ‘that’ and ‘there’.

Wrexham influence abroad is felt at Yale University in Connecticut, for one of its main founding benefactors, Elihu Yale, had family connections in this part of Wales, lived in Wrexham after retiring from the East India Company and is buried in the churchyard of St Giles’ church.

But it is not the famous, but rather the unsung heroes and heroines of Wrexham County Borough whose stories make up the backbone of this book. Jack Mary Ann, Mrs Five O’ Clock, Robin Ruin, Queen Eadburh, Lady Blackbird … you will meet them all in these pages. I hope you will feel you know this corner of Wales a little better as a result.

This book contains just thirty of the many stories with which Wrexham and its surrounding area teem; among those I’ve included are my favourites, as well as stories so well-known that they could not be left out if the collection were to be in any way representative – and also stories that were quite new to me and so delightful they had to be in …

But some of the stories I wanted to retell simply eluded me.

If only I could have found a shred of evidence to support a tantalising rumour that Lady Primerose of Berse Drelincourt had taken Bonnie Prince Charlie as her lover! That she secretly financed the Jacobite cause, even that he turned up unexpectedly at one of her parties in London, although in exile … all this can be verified, but – unfortunately for me – there is no way now of knowing if their relationship went any further.

If only I could have persuaded myself that Ruabon is named, not after St Mabon, the son of Bleiddyd ap Meirion, but rather after Mabon ap Modron, the lost hero who is rescued from prison in the great ancient tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ by two of Arthur’s knights, riding up the Severn Bore on the back of the giant salmon, which is the oldest of all creatures. However, to connect the story with Wrexham was a leap of faith too far, so I contented myself with retelling but then discarding that tale.

There are many more Wrexham folk tales than I could include, so I apologise if a story you hoped to find here is missing. You will not read about Brymbo Man here or any of the Sir Watkins Williams-Wynns who declared themselves ‘Princes in Wales’ over the generations.

But I hope you will find stories to delight you, to make you squirm, or snigger, or snooze …

If you like these stories, please take them and tell them in your own way. They belong to us all and are worth passing on. There is an old kind of wisdom in the tales, which should not be lost in this careless modern world.

And if you don’t like these stories, then please come to Wrexham County Borough to find some you do like. Come by train, bus, coach, car, canal boat, kayak, bicycle, motorbike or on foot, like George Borrow, to search out the stories that speak to you – and tell them instead! I shall look forward to hearing them.

Note

For more on the history of Wrexham see www.cpat.org.uk/ycom/wrexham/wrexham.pdf and Real Wrexham by Grahame Davies.

If you would like to read Mabon’s story and the rest of Culhwch and Olwen, since I couldn’t include it in this collection, I recommend Sioned Davies’ translation of The Mabinogion (Oxford University Press, 2007).

MAP

BANGOR-ON-DEE

1

THE MASSACREOFTHE MONKS

When the heathen trumpet’s clang

Round beleaguered Chester rang,

Veiled nun and friar gray

Marched from Bangor’s fair Abbaye;

High their holy anthem sounds,

Cestria’s vale the hymn rebounds,

Floating down the sylvan Dee.

O Miserere, Domine!

On the long procession goes,

Glory round their crosses glows,

And the Virgin-mother mild

In their peaceful banner smiled:

Who could think such saintly band

Doomed to feel unhallowed hand!

Such was the Divine decree,

O Miserere, Domine!

Bands that masses only sung,

Hands that censers only swung,

Met the northern bow and bill,

Heard the war-cry wild and shrill;

Woe to Brochmael’s feeble hand,

Woe to Aelfrid’s bloody brand,

Woe to Saxon cruelty,

O Miserere, Domine!

Weltering amid warriors slain,

Spurned by steeds with bloody mane,

Slaughtered down by heathen blade,

Bangor’s peaceful monks are laid;

Word of parting rest unspoken,

Mass unsung and bread unbroken;

For their souls for charity,

Sing, O Miserere, Domine!

Bangor! O’er the murder wail!

Long thy ruins told the tale,

Shattered towers and broken arch

Long recalled the woeful march:

On thy shrine no tapers burn,

Never shall thy priests return;

The pilgrim sighs and sings for thee,

O Miserere, Domine!

Written by Sir Walter Scott and set to music by Ludwig van Beethoven, 1817.

The massacre described in this poem is part history, part legend. Certainly it is historical fact that a great monastery once stood on the bank of the River Dee, in what is now Wrexham County Borough. It was described as ‘the mother of all learning’ but was so completely destroyed that archaeologists have found no trace of a religious centre that housed over 2,000 monks and an unknown number of lay brothers. The poet, however, is unlikely to have been correct in his assumption that there were also nuns there, for there is no evidence that the monastery at Bangor-on-Dee was a ‘double-house’ of the type established at Much Wenlock, Shropshire, by St Milburga.

When trying to reconstruct events which took place so long ago, history and legend soon collide. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and Brut y Brenhinoedd, its British equivalent, the battle recalled in this poem took place in AD 604, though more recent scholars give the date as AD 616. The historical facts of this bloodbath are difficult to determine. Legend, however, is quite definite in its version of events.

It was St Dunod who established the monastery of Bangor-on-Dee, or Bangor-is-y-coed, as it is named in Welsh, in the late sixth century. In the ancient verses known as the Welsh Triads, it is named as one of the Three Perpetual Harmonies of the island of Britain, for 2,400 monks lived there, divided into groups of 100. Each group ‘continued in prayer and service to God, ceaselessly and without rest’ for an hour at a time each day, so that there was never a moment when words of worship could not be heard there.

When St Augustine arrived in Britain from Rome in AD 597, his mission from Pope Gregory was to convert the pagan Angles of the kingdom of Kent to Christianity. The king of Kent, Aethelberht (sometimes called Ethelbert), was married to Bertha, the Christian daughter of the King of the Franks, so it is possible that he was already a Christian before Augustine arrived.

Augustine, having won over and baptised many of the Saxons, turned his attention to the Christians in the west of Britain. He wanted them to acknowledge the supremacy of Rome and accept the Pope as head of the Church; this the British were loath to do, as their Church had a tradition of its own, reaching back to the Romano-British era. However, they were prepared to enter into dialogue with Augustine, and so the seven foremost bishops of Wales agreed to meet with him at a certain tree, known as Augustine’s Oak, on the borders of Herefordshire and Worcestershire. The bishops were accompanied by monks from Bangor-is-y-coed, as it was regarded as a great seat of learning.

On their way, the monks met an old man, who asked where they were going.

‘We are going,’ they said, ‘to meet Augustine, who was sent by one he calls the Pope of Rome to preach to the Saxons. Now he asks us to obey him and to follow the ceremonies set out by the Church of Rome. Pray tell us, what is your opinion on this subject? Shall we obey him or not?’

The old man answered, ‘If God has sent him, obey him.’

‘But how can we know whether he is sent by God or not?’ they asked.

‘If Augustine is a meek and humble man, listen to him, but if not, have nothing to do with him.’

‘How shall we know whether he is proud or humble?’ asked the perplexed monks.

‘That is easily done,’ said their advisor. ‘Make your way to the appointed place slowly, to make sure that Augustine arrives before you and takes his seat. Now, he is only one, and I know that there are many learned and respectable men among you. If Augustine receives you humbly, you will know it at once, for he will not remain seated while you stand. But if he does not rise from his chair to greet you, you will know that he is a proud man. If this is the case, do not obey him.’

The monks accepted this advice gratefully, feeling that the old man must have been sent by God to help them in their hour of need. They thanked him and made their farewells, continuing their journey at a steady but slow pace, to ensure that they arrived after Augustine, so that the simple test proposed by the old man could be put into action.

When they reached the oak, they saw Augustine seated under its canopy in an elaborately carved chair, with seven empty chairs arranged around him, ready for the bishops of Wales to join him. However, as the monks approached, Augustine made no move to stand or even to greet them.

Instead, his face cold, he launched straight into a speech: ‘Dear brothers, though you hold many ideas contrary to our customs, yet we will bear with you, as long as you will, at this time, agree with us in three matters: to observe the feast of Easter according to the ways of the Church of Rome; to perform the ministry of baptism in the manner practised by the said Church; to assist us in preaching the gospel to the Saxons. If you will submit to us in these matters, we will bear with you, for a time, in other matters now in dispute between us.’

The monks exchanged glances. One of the bishops stepped forward to speak for them all.

‘We will not follow the Church of Rome, nor will we acknowledge you as our Archbishop,’ he said. ‘For as you were too proud to rise from your seat to greet us today, how much more will you despise us if once we submit to your authority?’

The chronicler gleefully records that Augustine’s blood ‘boiled within him’ as he replied.

‘Is that your story? Perhaps you will repent later. If you do not think it proper to join us in preaching the gospel to the Saxons, the time will come, and come soon, when you will receive death at their hands!’

This concluded the fruitless meeting. The bishops and monks of Wales returned to their homes, shocked by Augustine’s threatening words, but more convinced than ever that they had done the right thing in rejecting his proposals.

Augustine, however, set out to make sure his prophecy came true by urging the newly-converted Saxon king of Kent, Aethelberht, to take up arms against the troublesome Britons. Aethelberht raised his war band and called on his fellow Saxon, Aelfrith, king of Northumbria, to join him. The two armies set out for the floodplain of the River Dee, where now it marks the border between Wales and England, Wrexham and Cheshire.

From the decaying Roman stronghold of Chester, Brochfael, grandson of the great Powys leader Brychan Brycheiniog, prepared to defend the land and its people. He sent heralds to the Saxon leaders to sue for peace, but the Saxons killed the messengers and sent back their bodies as a silent and deadly answer. The battle which followed is known in the Welsh Triads as the Contest of Bangor Orchard.

Out from the monastery came a solemn procession of hundreds of pious monks, who had fasted for three days and were not afraid to die. They came to support Brochfael with the power of prayer, and gathered at the side of his troops, singing and calling for divine aid with such loud and united voices that Aethelberht demanded to know who they were.

‘We are the priests of the most high God,’ rang out a voice from the throng, ‘come to pray for the success of our countrymen against you!’

When he heard this, Aethelberht was furious, and ordered his men to attack the monks. The monks of Bangor-on-Dee put up no resistance, nor made any attempt to defend themselves but fell like barley at the harvest before the Saxon long knives, still singing as long as there was voice left in them. Then the Saxons turned on Brochfael’s troops and continued the slaughter. Bede calculated that about 1,200 monks who had come there to pray were slain that day, and only fifty or less escaped in flight.

The battle was a decisive victory for the Saxons and of great strategic importance in their campaign to control the island of Britain, for it pushed a wedge between the British kingdoms of Strathclyde and what is now Wales, leaving both increasingly isolated.

The Saxons went on to raze the monastery to the ground: no trace of it remains.

Note

The story of Augustine’s role in foretelling and ensuring the massacre of the monks of Bangor-on-Dee comes largely from Theophilus Evans’ Drych y Prif Oesoedd, literally translated as ‘a mirror of the early times’. This book, published in Bangor in 1740, is described in the National Library of Wales’ Dictionary of Welsh Biography as a ‘prejudiced and uncritical but very entertaining version of the early history of Wales’. Bede, writing in AD 731, gave an alternative version, more favourable to Augustine, in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People (book 2, chapter 2). Geoffrey of Monmouth gave a third account of the same events in his History of the Kings of Britain (xi 12 and 13).

BROUGHTON

2

JACK MARY ANN

Jack ‘Mary Ann’ Jones lived in Broughton at No.12 Top Boat Houses, Stables Road, Moss, with his long-suffering wife. She, of course, was Mary Ann.

They had a little stone house in a terrace on the hillside, with an excellent view down onto the single-track railway between Moss and Ffrwd. In fact, there was a good chance of seeing a train passing while you were sitting in the petty, the privy at the bottom of the garden, as long as you left the door ajar.

Jack worked for a while in the signal box on the GWR railway line down the valley. He might have worked there a lot longer if it hadn’t been for an unexpected visit from the district signalling inspector.

‘This is just a routine visit, Jack,’ said the inspector, ‘so I’m hoping you won’t mind answering a few questions.’

‘Fire away,’ urged Jack cheerfully.

‘Very well.’ The inspector took this as permission to give Jack a true grilling. ‘Say a passenger train were coming towards you up the line, but a coal train, heavily loaded, were running away downhill at speed because of a brake failure, and both were on the same track. As signalman, what would you do?’

‘Well, now,’ said Jack, looking confident, ‘I’d pull these levers here, which would move the signals to Danger, and that would let the two drivers know they need to brake.’

‘Very good, Jack, very good,’ nodded the inspector approvingly, ‘but suppose the signal wire were broken and the signal failed to operate?’

Jack Mary Ann

‘Then I’d change the points, fast as a nail in a sure place, and set the road to switch one of the trains – probably the downhill – into the sidings.’

‘Ah, but what if the points were jammed and couldn’t be moved?’ asked the relentless inspector.

‘Well, there’d only be one thing left for me to do,’ said Jack after due deliberation.

‘And that would be?’ prompted the inspector.

‘I’d run like hell to the Clayton Arms for Dic Dal-Deryn. He’s bound to be there. Then we’d both get back here as quick as …’

Jack got no further because the inspector interrupted him.

‘Just hold it a minute! Why would you be fetching this Dic Dal-Deryn? He’s not a railway employee, is he? What good would he be in this sort of trouble?’

‘Well, no good at all, of course,’ agreed Jack, ‘but we’re old mates, you see, and I know he’s never seen a train crash either.’

Sadly, this encounter, and particularly Jack’s attitude to the inevitable disaster the inspector had conjured, brought a sudden end to a promising career with the railway. However, never downhearted for long, Jack applied to join the police force instead. While waiting for his application to make its way through the official channels, he thought he’d have a night out with his friend Dic Dal-Deryn – a night poaching. Dic was an expert in this field, as shown by his nickname, which means ‘bird catcher’.

Dic and Jack arranged, over a pint in the Clayton Arms of course, to meet late on the night of full moon.

‘I’ll call for you from your house about two, Jack,’ said Dic. And so it was agreed.

Mary Ann went to bed at her usual time, but Jack said he would sit up a while longer before he followed her upstairs. Though she knew Jack well enough to be sure that something was up, Mary Ann simply sighed, kissed the top of his head and left him by the fire.

Jack was dozing in his chair when Dic tapped gently on the door. And tapped again. By the time Jack finally stirred, Dic was bashing at the door like one possessed. Upstairs, Mary Ann lay still, apparently fast asleep but actually listening to every word.

‘Jack, come on, Jack boi. Open up! What are you waiting for?’

Dic’s voice whistled through the keyhole, passed Jack’s snoring form and made its way upstairs to reach Mary Ann’s ears. She waited for Jack to respond, quietly amused to notice that he was almost as slow in replying to Dic as he would be to her.

‘Hmm? Umm? O, yes, Dic, yes, I’m coming. I’ll be right there.’

Blearily, Jack picked up his jacket and let himself out the back door. Mary Ann heard it close quietly behind him. She settled down with a sigh. Dic greeted Jack with another sigh.

‘What took you so long, Jack? I’ve been here for ages … let’s get going!’

‘I just need to go to the petty first,’ said Jack, ‘I shan’t be long.’

Dic almost groaned in frustration, but then thought: ‘Fair’s fair, when a fellow’s got to go …’

He leaned on the wall, while Jack blundered down the path to the privy, his jacket over one shoulder. Dic gazed at the moon and waited. And waited. And waited. Five minutes went by. Ten minutes went by. Why was Jack taking so long? Dic’s thoughts worked their way slowly from annoyed to concerned to worried. At last he decided he had better go to see what the matter was.

As he went down through the garden, Jack appeared from the privy at last.

‘You’ve taken your time,’ said Dic.

‘My jacket fell down the hole,’ said Jack. ‘I’ve been all this time trying to fish it out with a stick.’

‘Duw, boy, you won’t be able to wear that again, even if Mary Ann were to wash it for you,’ said Dic, wondering why on earth Jack had wasted valuable time on such a thankless task.

‘Well, I know that,’ replied Jack scornfully, ‘It’s not the jacket I’m bothered about. It’s my butties – they’re in the pocket!’

Up at the bedroom window, Mary Ann stifled a snort of laughter and climbed back into bed.

It was only a few days later that a letter arrived, inviting Jack to present himself for training as an officer of the law. He embarked on his new career with enthusiasm, and was soon a familiar figure faithfully patrolling his beat. It did not take him long to get to know every inch of it, particularly the many taverns and ale-houses, which needed visiting frequently to make sure that everything was in order. Of course, it would have been churlish to refuse any refreshment he might be offered by the landlords he visited, all of whom needed to keep on the right side of the law, and hence of Jack.

Jack liked his ale, so he continued to frequent the many drinking holes of Broughton, just as he had done before he had his ‘official’ reason for being there.

One night, as he propped up the bar in the Clayton Arms, his helmet on the counter beside him and his pint in his hand, an unfamiliar figure pushed open the door.

‘Is PC Jones in here?’ asked a deep unknown voice.

Jack saw the glint of metal buttons and heard the unmistakable heavy tread of standard-issue police boots.

‘I am,’ he said, coming forward into the light, pint glass in hand, ‘and you must be the new Police Sergeant.’

There was no reply, as Jack’s newly appointed senior officer stared in disbelief at the unkempt and unsteady figure of his constable.

Jack put his head to one side and admired the Sergeant’s trim uniform, before breathing beerily into his face, raising his glass in a toast, and saying: ‘You’ve got a good job there, boi, so mind you hold onto it as long as you can, for sure as eggs is eggs, I’ve just lost mine.’

In this, as in so many other things, Jack was quite right, and the long-suffering Mary Ann found herself once more trying to make ends meet and keep body and soul together, without a penny coming in from Jack.

Soon they fell behind with the rent. It didn’t take long until they were so far behind that it seemed as though the landlord might have to pay them to live there. Instead, of course, he sent his agent with a notice to quit. Jack was home alone at the time and saw the agent coming towards the house. Recognising him for what he was by the hat on his head and the papers in his hand, Jack didn’t answer the door. The agent knocked and knocked, and when no reply was forthcoming, crouched down to push the envelope under the door. Jack looked around, his mind working overtime, and grabbed the bellows from the fireside. Pumping them vigorously, he blew the notice to quit back out through the gap under the door. The agent tried again. Jack puffed it out again. And again.

Shaking his head in frustration, the landlord’s agent went round to the back door to try there. But Jack was ready, bellows in hand, and made sure that the papers fluttered out before they were properly in. At last the agent gave up, stuffed the papers in his pocket and turned away, muttering as he did so: ‘I’m not surprised Jack won’t pay the rent on a draughty old place like that.’

Jack felt pretty smug about this and thought he’d solved the problem, at least for a while. But the landlord came up with a more permanent solution, which, to everyone’s surprise, didn’t please Jack at all!