Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

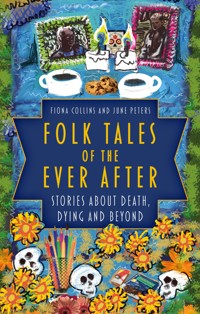

There is a time and a season to all things, and death is an inevitable part of the circle of life. Oral traditions from all over the world are full of stories giving shape to the very human wish to defy death – our own death and the deaths of others. Folk Tales of the Ever After is a collection of traditional tales from a range of cultures which is, by turns, funny, challenging and touching. From a man in Baghdad who tries to outrun Death, to Sir Lancelot's ride on the hangman's cart and an Ancient Sumerian ball game that leads to a trip to the underworld, storytellers Fiona and June invite you to share stories from their repertoire, and insights into their working practice, as a journey through the mysteries of death, dying,bereavement, loss, grief and the ever after.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 223

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In Memory of Ed and Robbie

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Fiona Collins and June Peters, 2023

The right of Fiona Collins and June Peters to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 395 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

Death is Part of Life

1 Death in a Nut

2 An Unexpected Meeting

Connections Between the Dead and the Living

3 Why Stones Live Forever

4 The Bedouin’s Gazelle

5 The Companion

6 Grandfather’s Flute

Defying Death

7 To the Mountains for a Brother, Through the Furnace for a Lover

8 Inanna’s Descent to the Underworld

Views of the Afterlife: Ancient Sumer

9 Enkidu

10 Gilgamesh

Views of the Afterlife: The Medieval World of Chivalry

11 Sir Orfeo

12 Lancelot and the Hangman’s Cart

The Dark Humour of Death

13 Sam’l and the Great Worm

14 The Hodja and his Death

Can Love be Stronger than Death?

15 The Long Welsh Tramping Road

16 Savitri and Satyavan

What Makes a Life Worth Living?

17 Death by the Pool

18 Oisin and St Patrick

Afterword

Acknowledgements

FOREWORD

BY ALIDA GERSIE

This is an intimate book. Oral storytelling is, of course, an ancient and intimate human tradition. However, the words ‘death and intimacy’ are less frequently uttered in one breath. And when they are, it is primarily to convey a sense of brokenness or rupture. Grief wounds us so. The death of people, pets and other beings hurts.

So, how can a collection of finely retold traditional stories about dying and death be intimate? The book generates intimacy mostly through the authors’ choice of stories. Taken together, this is an intriguing, occasionally defiant, and at times, a witty bunch of tales. Quite a few stories will be comfortably familiar, yet fresh in their retelling. Others are new gems. A warm quality is also generated through the stories’ arrangement in carefully thought through sections. Each section has a stirring personal introduction in which the authors’ creative humanity shines through.

The presence of birth, growth and death in our life is ubiquitous and irrevocable. Our own death is inevitable. This remarkable collection enables us to embrace the life that is ours to live that bit more humanely.

It is a bighearted gift.

Alida Gersie PhD, Enfield, August 2022 Writer, story-gatherer and consultant in personal change

INTRODUCTION

BY FIONA

The idea for a book of folk tales about death and dying was born when my partner Ed died, after a long illness, in January 2020. Ed and I had worked together on five books for The History Press, with me choosing the words and Ed creating images. This is the first book I’ve written that he hasn’t illustrated, and I was really glad when my closest friend June said she would work on it with me, contributing both images and stories.

My interest in death, and how humans think and feel about it, had already been fostered by taking part in Dying Matters Week events over some years, and by attending and hosting Death Cafés.

The traumatic death of my mother in 1990 had a long and profound effect on me. Family, friends and professionals were at a loss as to how to comfort me, until the wise storyteller Mary Medlicott suggested I read Alida Gersie’s book on bereavement, Storymaking in Bereavement: Dragons Fight in the Meadow.

Alongside her advice on the processes of grieving, and how to live with and through them, Alida’s book includes summaries of folk tales, myths and legends from around the world, exploring death, dying and grief. In all this treasure store, there was one image that really spoke to me: Inanna in the Underworld, hanging ‘like a corpse’ from a hook on the wall. This was exactly how I felt then: numbed, helpless, hopeless and cut off from life.

Reading Alida’s book created a connection between me and that story that has nurtured me for more than thirty years. Inanna had to be in this book. If you want to know more about the story, the goddess and the culture from which she comes, look for Diane Wolkstein’s book, co-written with the scholar, Samuel Noah Kramer.

Folk tales are made for retelling, and in the retelling, we all have the opportunity to use the tale to explore our beliefs and views and create new beliefs and new views. June and I have worked as professional storytellers in many settings for thirty years. We have chosen the stories for this book, both from our own repertoires and from the stories that other storytellers have offered us. We are telling these stories here, in our own words and in our own ways.

Our narratives contain fragments of folk wisdom, foolishness, belief, knowledge and jokes about death that have been passed on, first orally, then in written forms, around the world. Now we two tell them. When you’ve read them, you can tell them too.

REFERENCES IN THIS INTRODUCTION:

Alida Gersie, Storymaking in Bereavement: Dragons Fight in the Meadow (London: Jessica Kingsley, 1991).

Diane Wolkstein & Samuel Noah Kramer, Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth (New York: Harper & Row, 1983).

Dying Matters Week – www.hospiceuk.org/our-campaigns/dying-matters

Death Cafés – deathcafe.com

If you are troubled by anything in this book, the Samaritans offer a free and supportive listening service. They can be contacted by phone, letter, email or online chat.Samaritans’ website – https://www.samaritans.orgFreephone: 116 123Welsh language free phone line: 0808 164 0123.

DEATH IS PART OF LIFE

Oral traditions from all over the world are full of stories giving shape to the very human wish to defy death – our own death and the deaths of others. The Western, British culture, in which we were both raised, is notoriously resistant to thinking about death, although evidence that we are mortal and our lifespan time-bound is all around us.

Oour tendency is to behave as though we will live forever. This is often part of the shock when someone close to us dies – at some level, we didn’t really believe they would die, even if they were clearly very ill.

The story ‘Death in a Nut’ is, in many ways, our key text. A simple folk tale in the ‘Jack stories’ tradition, with a touch of humour as well as pathos, it carries at its heart a profound truth, that death and life are intertwined, and one could not exist without the other.

The story examines the denial or acceptance of death and their consequences. It carries to a logical conclusion the question ‘What would happen if nothing died?’ Jack learns that life extended beyond its purpose becomes unliveable and suffering inevitable.

The second story, ‘An Unexpected Meeting’, explores the same notion of ‘the right time to die’ from a different perspective. This is an Iraqi version of a common story motif, which again reminds us that death is invincible, and that there is no way to escape, trick or outrun it. There is a time and a season to all things, and death is an inevitable part of the circle of life.

1

DEATH IN A NUT

Imagine a cottage by the sea. Smoke curls from the chimney, chickens strut in the yard, fruit trees shade a pigsty.

That’s Mary’s home, where she lived with her son, Jack.

She had raised him from a baby on her own and, on the whole, she felt she had done a good job. He was even-tempered, kind to small children and animals, and useful for jobs that needed more than one pair of hands or required a bit of heavy lifting.

A cottage by the sea.

As Mary got older, she was more and more glad of his help. She was lucky with her health for a long time and neighbours complimented her on ‘keeping so well’, which she tried not to hear as a comment on her state of preservation, as though she were a pickle in a jar. But she knew, of course, that she was getting older, getting weaker. She tried to prepare Jack and get him thinking about what he would do when she was gone. But he always shied away from the subject. He just didn’t want to think about it.

Which is why Jack had a shock the morning he came downstairs to find the fire out, the kettle cold, the chickens still cooped up. What was going on? Mary was always up before him. Then he heard her call from upstairs …

He went back upstairs and put his head round her bedroom door. To his surprise, Mary was still in bed. She turned a pale face to him.

‘Jack, love,’ she said, ‘I’m not too good today, not good at all. In fact, I think my time must have come. I’ve had a good life, and I’m not afraid to go …’

Jack interrupted her. ‘Mam, what are you talking about? Don’t say such things! You’ve just got a bit of a cold, a touch of a virus. I’ll get you a nice cup of tea and you’ll soon be right as rain.’

‘Well, Jack,’ smiled Mary, ‘I wouldn’t say no to a cup of tea, but I do feel in my bones that Death will be calling for me today. And I do feel ready to go, though I’m sorry to be leaving you on your own …’

‘Mam, stop it now! Don’t say such things. Don’t even think them! Just lie there quietly and get better, and I’ll make your tea.’

And Jack scarpered downstairs before he could hear any more. He did the jobs his mother usually did, and he did them reasonably well. He lit the fire, set the kettle, went out to see to the chickens and pig, and came back to the singing of the kettle.

He made the tea and took it upstairs. His mother’s face looked grey and somehow transparent, and though he chattered away as though she would soon be fine, he felt a tightness round his heart that he had never known before.

Mary took his hands and made him meet her eyes. ‘Jack,’ she said, ‘I’ve had a good life, and I’m not afraid to go. I know you’ll be sad, but there’s nothing wrong with a bit of grief, and in time you will be fine. Now it seems to me that Death will be coming for me sometime today, so if you’d rather not be here when he calls, why don’t you go down to the beach for a while?’

Jack blustered and flustered for a bit, and even told his mother she was talking a load of rubbish, but eventually he agreed he would go and walk by the sea for a bit, though he insisted that by the time he came back she would be right as rain. He wouldn’t say goodbye, though he did let his mother kiss him.

When he came back, he was looking rather pleased with himself. Mary was sitting at the breakfast table. She smiled at him, though her face still looked pinched.

‘Are you feeling better, mam?’ asked Jack, giving her a hug. She felt thin and fragile in his arms, but he shrugged off any doubts. He kissed her cheek. ‘I said you would feel better after a bit of a rest, didn’t I?’

‘Well, yes, you did, Jack. I could have sworn that I was on my deathbed. But now … well, I do feel a bit better. I got downstairs. Are you hungry?’

‘Oh yes, mam. Are you?’

‘Not really, Jack …’

But Jack interrupted her.

‘You need to build yourself up now, mam. I’ll go out and get some eggs and scramble them for us.’

Jack went out and soon came back with a warm, brown egg in each hand. He carefully put one in a dish and tapped the other on the side of the pan. But it didn’t crack. He tapped harder. Then harder. Nothing happened. He tried the second one. But he couldn’t break that one either.

‘This is very odd,’ he said. ‘I really fancied scrambled egg.’

‘Well, never mind,’ said Mary. ‘There are some mushrooms and tomatoes in the larder. Would you like those on toast?’

So that’s what he had.

But for the rest of the day, Mary kept contemplating those stubborn eggs; rolling them in her hands and surreptitiously dropping them on the floor when she thought Jack wasn’t watching. She was wondering what was going on.

Because something definitely was going on.

This became clear the next day when Jack decided to go into the yard to kill their pig.

He was gone a long time. Mary looked up when Jack returned.

‘I can’t kill the pig,’ he said in a bemused voice. ‘The knife won’t go in. It just bounces off.’

In the days that followed, strange stories began to circulate in the village.

Lowri Davies’ pony broke its leg, and the vet simply couldn’t put it down.

Little Jimmy Jones, fishing in the creek, got so upset by the way his trout flapped on the bank for half an hour that in the end, he threw it back.

Granfer Phillips, 92 and at death’s door last week, seemed stuck on the threshold. He couldn’t pass over, but he couldn’t come back either.

No one, and nothing, could die. First it was a wonder. Then it was a mystery. But soon it became a crisis.

Stories began to circulate from the county abattoir: unkillable sheep, immortal swine, eternal cattle, coming in through one door and eventually being led out through another, alive and whole, when the place got too crowded to bring in more. Then news started coming from the area hospital: patients trapped in the grip of the most painful diseases; chronic infections going from bad to worse to unbearable; hopelessly premature babies clinging to life by the thinnest of threads that just wouldn’t break.

Mary knew Jack so well that she could read him like a book. She became convinced, by his guilty shuffle whenever some new oddity was reported by the neighbours, by the way he wouldn’t meet her eye when she tried to talk about her aches and pains, that there was a connection between her son and this strange new world in which nothing, and no one, could die.

She tried several times to broach the subject with him, but he always managed to find something urgent that needed doing, until one day she pinned him down.

Literally.

Mary got up early, groaning at the pains in her joints, and made two cups of tea. She took them into Jack’s bedroom and sat down on the edge of his bed, deliberately trapping him under the tightly drawn covers. ‘Jack,’ she said, ‘I’ve brought our tea up here this morning, so you and I can have a little talk.’

She looked at him meaningfully on the word ‘talk’, but he looked away, tugging at the counterpane, tight across his neck, and beginning to blether about thinking of going down to the beach to fish. But Mary was not to be deflected.

‘Well, Jack, it’s funny you should mention the beach, because I’d like to know a bit more about what happened on the beach, that day I woke up so poorly. What did you see, Jack? Or should I say, whom did you see?’

‘No one, mam, no one. The beach was deserted – it was quite a grey day, if you remember. Like today, but I still think it’s worth me seeing if I can catch something …’

‘And if you do, Jack love, how will you kill it? Do you want to see the poor fish out of its element, struggling and suffocating, and no end to its suffering? Because that’s what’s happening, Jack, all around us. Not just to fish, but to all kind of things – every kind of thing. What happened on the beach that day, Jack? What did you do, to change the way things always were, the way they should always be?’

Jack squirmed and squiggled, but Mary’s bottom was pulling the covers tight across his arms and legs, her eyes were boring into his. Even though he closed his eyes and turned his head, he knew she could see him – probably see his thoughts.

Jack cracked.

‘His scythe and all.’

‘O mam, I couldn’t bear to think of losing you. I saw him coming, coming to get you, with his scythe and all, and … and he thought he was so clever, but –’ Here, Jack’s voice grew more confident, and a gleam of triumph brightened his eyes. ‘But I tricked him!’

And Jack told his mother how he had flattered Death into showing off.

‘I tricked him! First, I asked if he could make himself big. He went really huge. He filled the sky! It was terrifying, to be honest, mam. But then I asked if he could go small as well. And he made himself tiny and helpless, so small he could fit into a nutshell. And I trapped him in it!’

‘And what did you do with the nut, once you had trapped Death inside?’ asked Mary, her voice gentle.

‘I threw it into the sea, mam, so he couldn’t take you, and then I came home, and you were alright!’

‘But I’m not alright really, Jack, am I? I was weak and in pain that day, and if it was bad then, it’s worse now. And there’s no release for me, Jack, no peace. Don’t you see, son, there is a time to live and a time to die, and if you push on past your time to go, then you suffer for it. I know you thought what you were doing was for the best, but it wasn’t right, Jack. And now it isn’t just me in trouble and pain, but every living thing whose time has come. It’s true that Death sometimes comes before we are ready, and that is hard for everyone. But for those who are ready, it’s much more terrible to be stuck in suffering and pain, when you could be free, believe me.’

Jack burst into sobs, and Mary gently reached out to him.

‘Son, don’t cry. I know you meant well, and I know you don’t want me to go, but it was my time that day. And now it isn’t just for you and me that the times are out of joint. You have to find a way to let Death back into the world. His work is as important as anyone’s.’

She let him sit up then, and as they drank their tea, they talked heart to heart. And what they said is none of our business. But the upshot was an agreement that Jack would go back to the beach to look for Death and let him out.

So off he went.

Even as he reached the beach, Jack was thinking, ‘This is ridiculous. This is impossible. It was a tiny hazel nut. I threw it into the sea. The great big sea …’

He wandered hopelessly along the high tide line, kicking at lumps of seaweed. ‘This is completely crazy,’ he thought. ‘I’ll never find it.’

Then his belly tightened. ‘But what if I don’t? Everything that’s going wrong: it’s all my fault. All I cared about was myself, not what mam wanted.’

A sob rose in his throat, and he threw back his head to stare despairingly at the indifferent sky. Then he dropped his gaze once more to the infinite beach.

And he saw it. Balanced on the edge of a little dip in a grey stone: a hazel nut. But surely not the hazel nut? That would be too incredible, too unlikely.

Jack knelt down and looked at it closely. He saw a little hole where a creature had gone in to eat the meat and come out again. And he saw the splinter that he himself had pushed into that hole, to keep the other creature, the one he had tricked, inside.

Gingerly, he picked up the hazelnut and cradled it in his palm. Feeling rather foolish, he nonetheless addressed it earnestly: ‘Is there anyone in there?’

A reply came, in a tinny little voice, ‘Yes, of course, where else could I be? Jack, is that you? You tricked me into this. You are the only one who can let me out. Do it, Jack. Now, please.’

‘But if I do, aren’t you going to do something terrible to me, in revenge?’ quavered Jack.

‘Is there anyone in there?’

‘Jack, I don’t take revenge. I don’t get emotional like humans. But I am getting tired of being cramped in here. And you know what a backlog of work I have got to deal with.’

‘Yes, it’s been really strange …’

Jack started to tell Death what the world had become without him.

But Death tutted impatiently. ‘Jack, I don’t need to hear your story. I just need to get on with things. Now stop chattering and do something useful, will you?’

Jack steeled himself, gripped the tip of the splinter and tugged it out of the hole. It was followed by a cloud of smoke, which quickly coalesced into a shadowless shadow on the sand.

Death harrumphed, shook out his robe, adjusted his cowl, inspected his scythe, got out his hourglass and tutted over it, then lifted his head and looked full into Jack’s eyes. ‘Jack,’ he began, not unkindly. ‘Do you understand things a bit more clearly now? Why life needs death and death needs life?’

‘Yes,’ muttered Jack, hanging his head. ‘Yes, I do. I’m sorry for meddling in the natural order of things. Mam explained it to me. And I saw it with my own eyes, too. Sometimes Death is cruel, and sometimes kind. It isn’t for me to interfere. But … but I do love my mam, and I don’t know if I can manage without her.’

Jack broke into sobs at this point.

Death, who wasn’t used to touching living flesh, patted him awkwardly on the shoulder. ‘Jack, you’ll be fine. Sad, but fine. And there’s nothing wrong with being sad – or so they tell me. Feelings are a bit of a mystery to me. But I really must go now. I am miles behind. If it’s alright with you, I’ll start with your mam. She is a wise one, and ready to go. Why don’t you stay on the beach for a while and watch the sunlight on the waves?’

‘Yes, I will, and thank you, and I’m sorry,’ mumbled Jack, looking out bleakly at the horizon.

‘There’s no need to apologise, only please, don’t try it again. At first, I was grateful for the break, but doing nothing soon palled. And that nut was terribly cramped. But now I really must be off. Goodbye, Jack, until we meet again.’

Jack looked round in alarm at these words.

‘No, don’t worry,’ said Death with a gravelly chuckle. ‘Of course, eventually we will meet again, but not for a long, long time.’

‘O, right. Goodbye then, Death,’ said Jack. ‘Until we meet again.’

And resolutely he fixed his eyes on the horizon, as Death set off towards his delayed appointment with Mary, who calmly welcomed him into the little cottage by the sea, with a last soft sigh.

2

AN UNEXPECTED MEETING

A rich merchant living in Baghdad sent his most trusted servant to the market to buy spices. As the man pushed through the crowds jostling around the colourful stalls, someone bumped into him. He turned to warn them to take care, only to find himself staring into the face of Death. Death looked straight into the horrified man’s eyes, opened her mouth to speak and reached out her hand.

He did not stop to hear the words he dreaded. He turned and fled. When he got home he threw himself on his master’s mercy. ‘Lord, help me!’ he begged. ‘In the market place Death came for me. I saw that terrible face, close to mine. That bony hand reached out to clutch me … I am not ready to die! I beg you, lend me a horse so that I can outrun it!’

‘When Death comes, it surely is our time, even though we may not think so,’ said his master, who was a student of philosophy. ‘But, since you are so afraid, I will do my best to help you. Take the fastest horse, with my blessing. Where will you go?’

‘To Samara – thank you!’ cried the servant, running from his master’s presence straight to the stables.

A few moments later, the merchant heard the clatter of hooves over the cobbles. He sat and listened, until the sound grew fainter and faded away.

Four hours of fast riding.

‘Hmm,’ he said to himself, ‘He has fled, and Samara is more than 130 kilometres away. But I ask myself whether anyone can escape Death when she truly comes for them. And now I must go to the market myself, if I am to have the spices I need.’

He rose with a sigh, and went down to the market, which was still in full swing. As he made his way towards the pungent stall where the finest spices were on display, the merchant saw that Death was still there in the marketplace. She passed unnoticed among the busy shoppers, but this merchant was a learned man, and he recognised her at once.

He was also a fearless man, for instead of imitating his servant and running away, he went straight up to Death and engaged her in conversation. ‘Death,’ he said, courteously but firmly, ‘Only a short while ago, you gave my good servant a terrible fright. He told me that you reached for him, as though to speak.’