Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd.

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Serie: QuintEssentials of Dental Practice

- Sprache: Englisch

Bleaching has been scientifically proven to be simple, safe and effective. It has revolutionised dentistry. When used sensibly this non-destructive approach has enabled many patients to benefit significantly at very low biological risk and reasonable financial cost. Inside/outside bleaching has dramatically reduced the destruction of teeth caused by the placement of post crowns in already damaged teeth.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 142

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Quintessentials of Dental Practice – 38Operative Dentistry – 6

Dental Bleaching

Author:

Martin G D Kelleher

Editors:

Nairn H F Wilson

Paul A Brunton

Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd.

London, Berlin, Chicago, Paris, Milan, Barcelona, Istanbul, São Paulo, Tokyo, New Delhi, Moscow, Prague, Warsaw

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Kelleher, Martin Dental bleaching. - (Quintessentials of dental practice; v. 38) 1. Teeth - Bleaching I. Title II. Wilson, Nairn H. F. 617.6’34

ISBN: 1850973199

Copyright © 2008 Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd., London

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 1-85097-319-9

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Titelblatt

Copyright-Seite

Foreword

Preface

Chapter 1 Chemistry and Safety of Dental Bleaching

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Chemistry

Chemistry of Hydrogen Peroxide

How Hydrogen Peroxide Works

How Teeth Become Discoloured

Safety of Carbamide Peroxide

Sensitivity

Soft Tissues

Tooth Resorption

Pulpal Considerations

Effects on Hardness of Teeth

Amalgam Restorations

Tooth-coloured Restorative Materials

Adhesive Bonds and Rebound

Chair-side Bleaching

Unfounded Fears

At-risk Groups

Efficacy and Effectiveness

Mouth Rinses

References

Further Reading

Chapter 2 Nightguard Vital Bleaching

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Development

Patient Management

Pre-examination Questionnaire

Protocol

Clinical Procedures

Tray Design

Trays with Reservoirs

Scalloped Trays

Straight-line Trays

Single-tooth Trays

Combination Trays

Technical Procedures

Fitting the Tray

Evaluation of Colour Change

Instructions for Patients for the Use of 10% Carbamide Peroxide

Notes

Sensitivity

Rebleaching

Bleaching dos and don’ts for the dentist

Reference

Further Reading

Chapter 3 Management of Discoloured Dead Anterior Teeth

Aim

Outcome

Discoloured Dead Teeth

Assessment

Aetiology

Mechanisms of Discolouration

Monitoring

Inside/outside Bleaching

Protocol for Inside/outside Bleaching

First Appointment

Making the Tray

Second Appointment

Instructions for Patients

Problems and Troubleshooting

Poor Patient Compliance

The Neck of the Tooth Does not Bleach

Failure to Bleach

Discolouration Difficult to Manage

“Walking bleach”

Chair-side bleaching

Restorative Options

Porcelain or composite veneers

Crowns and post crowns

Further Reading

Chapter 4 Bleaching of Teeth Affected by Specific Conditions

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Fluorosis

Appearance of Fluorosis

Cause of Fluorosis

Swallowing Toothpaste

Management of Fluorosis

Protocol for Bleaching Fluorotic Teeth

Treatment Times

Troubleshooting

Microabrasion

Tetracycline Discolouration

Mechanisms of Discolouration with Tetrocyclines

Breakdown of Tetracyclines

Clinical Presentations

Bleaching vs Conventional Prosthodontics for Tetracycline Discolouration

Differential Diagnosis

Prevention

Treatment ProtocolM

Banded Tetracycline Discolouration

Efficacy

Time and Cost Implications

Congenital Conditions

Dentinogenesis Imperfecta

Clinical appearance

Treatment

Amelogenesis Imperfecta

Hypoplasia, hypocalcification, hypomaturation

Further Reading

Chapter 5 Chair-side Bleaching

Aim

Outcome

Chair-side Bleaching

History

Mechanism

Technique

Patient Assessment

Safety

Isolation of the Teeth

Isolation using rubber dam and caulking material

Using rubber dam and floss

Sensitivity

The Bleaching Material

Storage

Application of Bleaching Material

Acceleration Techniques

Increasing the Concentration of Hydrogen Peroxide

Use of Light-activated Catalysts

Use of Heat and Light

Concentration and Efficacy

Effectiveness

Light-assisted Chair-side Bleaching

Lights and Heating Devices

Proprietary Bleaching Systems

Cost of Lights and Materials

Further Reading

Chapter 6 Over-the-counter Bleaching Products

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Bleaching Strips

Paint-on Gel

Problems with Over-the-counter Products

Whitening Toothpastes

Further Reading

Chapter 7 Frequently Asked Questions

Aim

Outcome

What Causes Tooth Discolouration?

Are There Any Other Causes of Discolouration?

What Happens During Bleaching?

Are There Any Contraindications to Bleaching Teeth?

How Much will it Cost?

Does the Patient Have to Sleep with the Bleaching Tray or Mouth-guard in Position?

Are there any Side-effects?

Can the Sensitivity be Reduced?

Which Toothpaste Should be Used when Bleaching?

How Long will Bleaching Take?

Is Chair-side (also Known as “Power” or “In-surgery”) Bleaching Better than Nightguard Vital Bleaching?

How Long does Bleaching Last?

What is the Best Material to Use?

Why Not Use Over-the-counter Products as Advertised on TV and in Magazines?

Are Whitening Toothpastes Effective?

How Much Carbamide Peroxide Gel is Swallowed During Bleaching with a Bleaching Tray?

Is Swallowing Hydrogen Peroxide Harmful?

Further Reading

Chapter 8 Information for Patients

Aim

Outcome

Nightguard Vital Bleaching

What Does Nightguard Vital Bleaching Involve?

How Long Does it Take?

Will I Have to Keep Bleaching?

Is it Safe?

Is it Effective?

When Does it Work?

Discolouration linked to ageing and diet

Fluorosis

Tetracycline discolouration

Will There be Problems with Existing Restorations, Fillings or Crowns?

What about Side-effects?

Sensitivity

Soft tissue discomfort

What about Chair-side Bleaching?

Other Methods of Treating Tooth Discolouration

Microabrasion

Composite

Porcelain Veneers

Crowns

Extraction

Chapter 9 Complications and Contraindications

Aim

Outcome

Overbleaching

Wrong Order of Bleaching

Bleaching of Teeth Restored with Composite

Inappropriate Timing of the Placement of Restorations

Failure to Recognise Restorations

Very Dark Teeth

“Retchers”

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Xerostomia

Further Reading

Foreword

Bleaching, although not new to dentistry, has recently become extremely popular. It has the great advantage of being minimally interventive and, assuming correct use, safe. In addition, the appropriate application of bleaching agents and techniques does not adversely affect the integrity or properties of sound tooth tissues.

As emphasised in this most attractive addition to the multidisciplinary Quintessentials series, practitioners and students must not be lulled into a false sense of complacency by the apparent simplicity and versatility of most bleaching techniques. Careful diagnosis, informed treatment planning, patient consent and cooperation and effective troubleshooting are all critical to predictable success and good, long-term clinical outcomes. Bleaching is best provided as part of the holistic care of patients seeking, together with other outcomes, an improvement in their dental attractiveness. While long-term outcomes of bleaching can be excellent, monitoring and “top-up” treatments may be required as part of longitudinal, patient-centred care.

Whatever your views on bleaching and your application of tooth lightening techniques in your clinical practice, this Quintessentials volume will be a great asset. It is succinct, authoritative, beautifully illustrated, affordable and, above all else, of immediate practical application and relevance. What more could the busy practitioner or student wish of a book? Pragmatism: well it has that too, and in abundance. For a fraction of the cost of a bleaching treatment, this Quintessentials volume is, in common with all its sibling volumes, quintessential value for money.

Bleaching is firmly established as an element of the modern clinical practice of dentistry, and practitioners and students must understand the mechanisms, application and pitfalls of the relevant techniques. This book meets these needs, and provides an opportunity to be one step closer to satisfying the ever-increasing expectations of patients.

Congratulations to the author on a job well done.

Nairn Wilson Editor-in-Chief

Preface

Bleaching has been scientifically proven to be safe and very effective in altering the colour of teeth. Discoloured teeth are up to five times more worrying to patients than crooked teeth.

While bleaching has been used in dentistry for nearly 200 years, the recent impetus for its use came from the seminal work of Haywood and Heymann in 1989.

Diagnosis of the causes of discolouration, assessment of patients’ expectations and full discussion with patients about their available options are all important aspects of bleaching.

Bleaching is now well established as one of the most important appearance-enhancing aspects of modern, evidence-based clinical practice. This book outlines the mechanisms and techniques involved. It also draws attention to some of the pitfalls of dental bleaching and how many of these can be avoided with a sensible, patient-centred, deductive, pragmatic approach.

Bleaching in combination with composite or porcelain bonding can produce results that compare very favourably with much more destructive and expensive traditional crown techniques. Unlike bleaching, many of the alternative more destructive techniques produce negative biological outcomes at considerably greater expense in terms of tooth tissue, time and money.

Bleaching leaves patients with one of their most important assets – good, clean looking, healthy, attractive enamel. Dentists have sought for years to produce natural looking replacements for enamel. Many of the supposedly miraculous porcelain materials produce dismal long-term results. If dentists just had the good sense to leave enamel on the teeth in the first place, there would be many fewer biological and aesthetic problems with teeth in the longer term.

It is prudent to reflect that “less is more” in dentistry. The change away from a destructive mechanical approach to a biological minimally invasive one is to be welcomed. This could be best described as a change from “Meccano to microns” with the gradual realisation that much less damaging dental procedures are worth more to patients than destructive ones. Bleaching in this context, if sensibly applied according to scientifically validated principles, can reasonably be expected to produce good long-term results. This confidence is based on multiple, randomised, double blind, controlled trials.

The book also draws attention to some of the highly publicised but less well proven, if not unsubstantiated, claims made in respect of certain forms and aspects of bleaching.

This book could not have been done without the help of Margaret Buck, who patiently typed all my drafts. My wife Annette provided invaluable (usually constructive) criticism throughout the project.

My thanks are also due to Nairn Wilson for his skilful editorial assistance.

Martin Kelleher

Chapter 1

Chemistry and Safety of Dental Bleaching

Aim

The aims are to introduce the chemistry of bleaching, to describe how teeth become discoloured and to demonstrate the safety of bleaching techniques.

Outcome

On reading this chapter the practitioner will be more familiar with the chemistry of bleaching discoloured teeth and be reassured as to the safety of dental bleaching.

Introduction

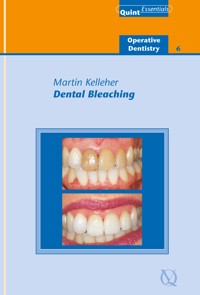

Bleaching is a chemical process involving the oxidation of organic material which is broken down to produce less complex molecules. Most of these smaller molecules are lighter in colour than the original larger molecules. Figs 1-1 and 1-2 show teeth before and after bleaching.

Fig 1-1 Before bleaching.

Fig 1-2 After bleaching.

Chemistry

The oxidation/reduction reaction which takes place with bleaching is known as a redox reaction. In a redox reaction hydrogen peroxide – the oxidising agent – releases free radicals with unpaired electrons, thereby becoming reduced. The discoloured molecules within the teeth accept the unpaired electrons and become oxidised, with a reduction in the discolouration.

Hydrogen peroxide is an oxidising agent which produces free radicals HO2• and O• which are very reactive. The perhydroxyl ion HO2• is the stronger and more reactive of the two free radicals. For HO2• to be made readily available the bleaching material needs to be alkaline. The optimal pH for HO2• release is around pH 10.

Chemistry of Hydrogen Peroxide

The empirical formula for hydrogen peroxide is H2O2. The structural formula is HO–OH. The molecular weight of hydrogen peroxide is 34.0.

The empirical formula for carbamide peroxide is CO(NH2)2H2O2. The structural formula is

The molecular weight of carbamide peroxide is 94.1.

How Hydrogen Peroxide Works

The whitening effect is caused by the degradation of high molecular weight complex organic molecules that reflect a specific wavelength of light responsible for the colour of the stain. The degradation products have relatively low molecular weights and, as such, are relatively simple and with less colour reflectance. Bleaching results in a reduction or elimination of the discolouration. Both enamel and dentine change colour as a result of the passage of the peroxide through the tooth.

During dental bleaching hydrogen peroxide, which has a low molecular weight, readily penetrates through the interprismatic substance of the enamel to enter dentine and pulp. Because the free radicals have unpaired electrons they readily react with, and attack, most organic molecules. In the process, they generate other radicals. These radicals react with unsaturated bonds, resulting in the disruption of the electron configuration of those molecules. Hydrogen peroxide is capable of undergoing numerous reactions, including molecular additions, substitutions, oxidations and reductions. It is a strong oxidant and can form free radicals by homolytic cleavage.

The various chemical reactions produce a change in the absorption energy of large discoloured molecules within the enamel and dentine. The large molecules are broken down into smaller molecules, with the loss of the unsightly discolouration.

Complex molecules, in particular those forming metallic compounds, look dark whereas simpler molecules look lighter. By breaking down the larger molecules into smaller ones, most are dissipated. Those remaining tend not to have a darkening effect. The result of these various changes is a lighter-looking tooth. In the process of bleaching, highly pigmented carbon ring compounds within the tooth can be broken down and turned into relatively simple chain molecules. Many of these chains have consecutive conjugated double bonds which are further broken into single bonds. These are hydrophilic colourless or lightly pigmented structures.

Theoretically, if bleaching is carried on indefinitely, damage could occur to the enamel matrix. This, however, is largely a theoretical concept. Optimal bleaching involves lightening the teeth to an aesthetically pleasing shade, usually agreed with the patient, while preserving the hardness and strength of the enamel.

How Teeth Become Discoloured

The interprismatic substance between enamel prisms acts like a wick, drawing up ions and small molecules from the oral fluids. Complex molecules – pigments and dyes – stain the interprismatic substance. A pigment is a coloured substance composed of a colour-bearing group (a chromophore) and other molecules. Pigments may, or may not, attach to the organic material in the interprismatic spaces (Fig 1-3).

Fig 1-3 Definition of a pigment.

A dye is a pigment with reactive (hydroxyl or amine) groups which can attach to organic matter (Fig 1-4). Common dyes come from coffee, tea, curry, tomato sauces and red wine. Melanoidins are formed from the breakdown products of cooked vegetable oils. Metal compounds can interact with dyes to form larger compounds, which produce different colours of stain. Metal compounds containing iron and copper are often involved (see Figs 1-5 to 1-7).

Fig 1-4 Definition of a dye.

Fig 1-5 Gradual assembly of complex stains within the teeth. Note the contrast with the old crown at the upper left lateral incisor, which previously matched the teeth.

Fig 1-6 Discolouration build-up in teeth.

Fig 1-7 Breakdown of stain.

An increase in the size of a dye increases the affinity of the dye for the organic matter in the interprismatic space. Hydrogen peroxide breaks up large molecular stains into smaller molecules, most of which are expelled through the surface of the tooth. The perhydroxyl ions may attach to molecular stain as well as the protein matrix.

Bleaching produces oxidation which involves the breakdown of ring structures and consecutive, conjugated double bonds in complex molecules. This results in loss of colour caused by unwanted dark molecules in the non-cellular matrix. Hydrogen peroxide works by converting these large molecules into alcohols, ketones and terminal carboxylic acids. As these are smaller molecules which may be expelled from the tooth, the clinical effect is that the tooth is lightened (see Figs 1-8 and 1-9).

Fig 1-8 Discoloured upper left central incisor before bleaching.

Fig 1-9 Upper left central incisor after bleaching.

Safety of Carbamide Peroxide

Carbamide peroxide is formed from hydrogen peroxide and urea. About one-third of carbamide peroxide is released as hydrogen peroxide. A 10% solution of carbamide peroxide releases about 3.5% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2 ). A 15% solution of carbamide peroxide releases about 5% hydrogen peroxide. Urea is a normal bodily constituent. The urea component of carbamide peroxide used in dental bleaching is of no biological consequence. Hydrogen peroxide is found in all body cells as an endogenous metabolite. The human liver, the principal site of metabolism, produces up to 270 mg of H2O2 per hour.

Hydrogen peroxide is rapidly decomposed by enzymes, in particular catalase and various peroxidases. Saliva contains catalase and peroxidases which rapidly break down any hydrogen peroxide released in the mouth during bleaching. These protective mechanisms ensure that the intraoral release of hydrogen peroxide from carbamide peroxide used in dental bleaching has no adverse effects.

All body cells contain enzymes which protect against hydrogen peroxide. The highest levels are found in the liver, duodenum, spleen, blood, mucous membranes and the kidneys. Most of the catalase is found in the red blood cells, which can degrade gram quantities of hydrogen peroxide within a few minutes. The overall decomposition reaction of hydrogen peroxide in the presence of catalase is

H2O2 + H2O2 → 2H2O + O2 (water and oxygen)

In the presence of peroxidases the reaction is

H2O2 + 2RH → 2H2O + R-R

Hydrogen peroxide is broken down into oxygen and water by enzymes such as catalase, peroxidases and selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidases. If any bleaching gel is present in the mouth then the catalase and peroxidase enzymes in saliva will rapidly inactivate it.

Dermal toxicity is low. There is no evidence in the available literature that hydrogen peroxide is a skin sensitiser in humans. Very occasional positive patch tests have been reported.

Biological membranes are highly permeable to hydrogen peroxide. Hydrogen peroxide is readily taken up by the cells of the oral mucosal surfaces, but at the same time it is quickly metabolised. There is uncertainty as to the extent to which hydrogen peroxide enters the bloodstream, given the variable amounts of existing endogenous hydrogen peroxide. In any event, hydrogen peroxide is, as indicated above, rapidly metabolised by red blood cells.

The risk posed by the use of carbamide peroxide for dental bleaching is very small, but there is nothing to which human beings are exposed that is entirely free of risk. The concentration or the dose is the critical issue in any consideration of toxicity. According to toxicologists, “the dose makes the poison”. Provided that the concentration of hydrogen peroxide is low and the dose is small, any risk of adverse reaction is very limited.

The toxicology of hydrogen peroxide was reviewed by the International Association for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 1985, by the European Centre for Ecotoxicology and Toxicology of Chemicals (ECETOC) in 1993 and by Li in 2003. These reviews concluded that there are no reasons for concern about the use of hydrogen peroxide in the concentrations employed in dentist-prescribed at-home bleaching.