Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

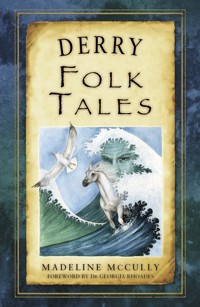

This lively and entertaining collection of folk tales from the County Derry is rich in stories both tall and true, ancient and recent, dark and funny, fantastical and powerful. Here you will find stories of mythical beasts such as the Lig-na-Paiste, banished by St Murrough to Lough Foyle; the dark tales of Abhartach, the Irish Vampire, and the reason a skeleton features of Derry's coat of arms; the cautionary tale of the man who raised the Devil and who never spoke another word for the rest of his life; and, of course, the legends of the great St Columba, founder of the City of Derry, whose prayer reputedly still protects its inhabitants from ever being struck by lightening. These well-loved and magical stories, retold by professional storyteller Madeline McCully and richly illustrated with enchanting line drawings, are sure to be enjoyed and shared time and again.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 282

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

I dedicate this book to my grandchildren, in the hope that they will cherish the wonder of childhood and never grow too old to enjoy a good story.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

How can I begin to acknowledge the people who have contributed to these stories? Some are still alive while others have passed on and left a legacy of stories.

My thanks go firstly to my darling husband Thomas, who was forever supportive and encouraging. Thanks to the family for putting up with my absences (and absentmindedness).

Beth Amphlett of The History Press Ireland was a delight to work with and was considerate, approachable and ready to answer queries at all times.

I thank Margie Bernard of Derry Playhouse Writers who lovingly pushed me to write and Professor Georgia Rhoades who taught me to use those writing skills in her workshops.

I appreciated all the help given to me by Maura, Jane and Linda of the Derry Central Library and the staff of Shantallow Library, Mary, Emma, Diane and Marie-Elaine. They made research a pleasure.

I thank Jim McCallion of North West Regional College for his unfailing patience as he helped me improve my computer skills.

To all of those who shared stories, snippets and factual backup I want to say a big ‘thank you’. Although I could not include all of the material, it is still floating around in my mind and will no doubt emerge in a storytelling session or two or maybe another volume.

Ken McCormack has a treasure trove of strange happenings and was always interested and interesting when I spoke to him. I want also to acknowledge Sean McMahon whose translation from Irish into English of The Waterside Ghost was begging to be included and I thank him for his permission to do so and hope that he forgives the slight meanderings from it.

I would like to mention those who reawakened my interest in folklore and who gave me a listening ear over the years, Liz Weir for her inspirational stories, the late Sheila Quigley who founded Foyle Yarnspinners and who was always so generous with her time, Bertie Bryce who taught me to ‘recite’ and Pat Mulkeen who was my ‘Storytelling friend’.

Lastly I want to let my nurturers, Marilyn, Cora and Ellen, know how much I appreciated their listening and advice as I put this volume together.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

Folk Tales of Derry

1. Columcille: Dove of the Church and Founder of Derry

2. Derry’s Coat of Arms: The Story Behind the Skeleton

The Legends of Lough Foyle

3. The Borrowed Lake

4. Feabhail Mic Lodain and the Origin of Lough Foyle

5. Manannán Mac Lír

6. The Death of Princess Túaige – the Goddess of the Dawn

7. White Hugh (Aed) and the Rout of the Vikings

8. The Mermaid of Lough Foyle

9. Cuil, the Man who made the First Harp

10. Black Saturday on the Tonn Banks

Devil and Vampire Tales

11. The Legend of Abhartach, the Irish Vampire

12. The Man who Raised the Devil

13. Dan and the Devil

14. The Devil and the Bishop

15. The Devil and the Gamblers

Local Tales

16. The Waterside Ghost

17. Cahir Rua O’Doherty

18. Robert Lundy and the Great Siege

19. The Blind Harper, Denis O’Hempsey

20. The Rapparee, Shane Crossagh O’Mullan

21. Amelia Earhart’s First Solo Trans-Atlantic Flight

22. The Legend of Danny Boy

23. The 116-year-old Woman

Sidhe Folk

24. The Gem of the Roe and the Banshee Gráinne Rua

25. The Lovesick Leannan Sidhe

26. Biddy Rua and the Poteen Makers

27. The Whiskey Smugglers and the Fairies

The Fairy Curses and Charms

28. Blinking the Cattle

29. Blinking the Churn

30. John and the Fairy Tree

31. Nursing a Baby That’s Not of My Own

32. Brogey McDaid and the Wee Folk

33. Pauric and the Fairies

Fairy Beasties

34. Lig-na-Paiste (The Serpent in the Pool)

35. The White Hare

36. The Tale of Cadhan’s Hound

Traditional Tales

37. The Wish

38. The Looking Glass

39. What You Want is Not What You Need

Bibliography & Further Reading

Copyright

FOREWORD

I feel I have two homes, though I live in neither. One is Kentucky, which I left over 20 years ago. In a hollow near the house where I grew up, in the right conditions, you can hear a wagon and horses approaching from the top of the hill through the woods. They will pass right by the porch of the beautiful old house in the hollow, but you won’t see them, only hear them. In the house, a starving woman goes through the cabinets in the kitchen at night, looking for bread. Those who live there will tell her to eat her fill, but she never is satisfied.

Some of these places were written about by Lynwood Montell in Ghosts Along the Cumberland, and for us that was a vindication of our history, that our stories had become larger than our small community, and that we were linked in that great web of folklore. Like Madeline, who has listened to storytellers and gathered a great collection of her own stories, I grew up with tales and myths told by old people. In my childhood, I saw butter churned and almost everyone I knew kept a cow or two, so such tales as ‘Blinking the Cattle’ and ‘Blinking the Churn’ are particularly evocative for me. My mother told me of smoke rising from most of the hollows when she was a girl in the 1920s, evidence of moonshine stills and our version of poteen. There were bullet holes in the door of the church, and a story to go with them; a tale of the dog nobody knew who came into a house to bite the son, who could not be cured by the madstone; and a story about two sisters who murdered their father one warm night. These stories may not have the grandeur of the skeleton on the Derry coat of arms or the patina of antiquity in Columba’s exploits, but they do link Kentucky, which the Cherokee called ‘the dark and bloody land’, to the Irish and Scots who settled there and saw stories as a way to narrate who we are and why we are here.

The other place I feel at home is Derry, which I have been lucky to have visited more than twenty times. Through my writing, Derry’s history has become even more important to me than Kentucky’s. In preparation for writing my play The Cook, about the execution of Cecily Jackson at Bishop’s Gate in 1725, I read the Bishop’s diary, where he speaks of his fear of ‘the murderous Rapparee’, given life in this collection by Madeline. I was recently in the excellent Tower Museum, looking for context about Derry in the eighteenth century, and I will return to pay closer attention to Sir Cahir O’Doherty’s sword, now that I know its story. Madeline also makes history alive in such stories as Amelia Earhart’s and Denis O’Hempsey’s.

What is heartening in all these accounts is how they link communities in our need to make meaning, to turn an event into a narrative. The story of ‘The Waterside Ghost’ resonates with what seems to have been a haunting at the house of Ann Haltridge in the Islandmagee legend I recently researched for a play I am writing. The story of Willie the fisherman fits with a wealth of Irish folklore about mermaids, from Lough Neagh’s Liban to the mermaid who sits by Lough Derg, combing her hair. The white hare has a counterpoint in Scotland in the boasting of Isobel Gowdie and in Cornish stories of witches becoming hares, and the Feeny dragon recalls the Arbroath waterhorse who lurks beneath the kirk on the hill, waiting for the unwary who cross the bridge.

Those of us who have been able to hear Madeline tell stories will recognize her powerful voice in these tales and imagine that she is talking to us as we sit in a firelit circle. Her storytelling power is in evidence throughout the book, as in this creepy passage in which she prepares us to approach the place we will meet the Irish vampire: A lone thorn tree would guide you to it but when you’d arrive you would see no grass or vegetation growing there and an enormous stone lies over the grave.

Madeline’s work in compiling these stories helps us know who we are and what we believe possible, or, for some, what we believe probable. In this collection, she honours folk wisdom and creativity, listeners and tellers, and the circle in which we sit together.

Dr Georgia Rhoades

Boone, North Carolina

July 2015

INTRODUCTION

Most stories are unique to the person who tells them and although there are times when reason tells you that something could not have happened the way it was told, it is better just to listen and enjoy the moment. It is well known in Ireland that a wee bit of embellishment has made many a dull story better. The folklore of Ireland is littered with tales of taboos, fairies, superstitions, ghosts and banshees. The list is as endless as the Domesday Book but unfortunately many of our stories are being lost in this modern age when technology provides entertainment for the young and the not so young.

I am old enough and lucky enough to have experienced the ‘big nights’ or ‘ceilidhe nights’. Most summers until I was a teenager I went on holiday to my great-aunt’s house in a rural part of Ireland. In those kinds of places people made their own entertainment; the fiddle and melodeon led the dancing and singing and as the night went on and the music stopped, it was then that the stories began. We youngsters opened the kitchen door a crack and listened to the big folk talk.

I heard many a story in my grandfather’s house too, for he was a countryman who moved into the town. Looking back, the stories were told with such conviction and drama that I believed every one of them at the telling. The tales brought me into a realm beyond the ordinary with their use of rich language and the Gaelic construction of the sentences, for often, the people were barely a generation away from the Gaelic language itself.

One of the recurring things I remember as I look back nostalgically on those evenings is that stories were mainly told in the negative interrogative. It wasn’t enough to say that I met someone on the way to the well, no, it was told in a much more engaging way.

‘Didn’t I decide to go to the well to fill the bucket and what d’ye think happened? Didn’t I see wee Johnnie’s Mickey walking down the road and him all of a fluster. Sure, did I not stop him and say tae him, “What ails ye?”’ And so the story of a normal meeting became a tale, and we pulled our chairs closer to hear what the matter was with Johnnie’s Mickey.

Most of the stories were about life around and about the district but on the occasions of ancient festivals like May Day, Lughnasa and the like, stories echoed the ancient ones. Samhain-Halloween was the time for ghost stories, and sometimes the listeners stayed in the house till daybreak for fear of meeting a ghostly spirit if they ventured out on the way home. If you believed it, the wee folk were more numerous than humans and were always a popular source of stories. There were stories of the colour red, hawthorn trees, fairies and iron, fairy pathways, the new moon, spilling salt, raths, standing stones and if you lived to be a hundred you would still discover more.

Many years ago, I interviewed three marvellous storytellers for the radio. They inspired me, and even though they have passed on, I remember them with gratitude and affection, they were Sheila Quigley, Bertie Bryce and Pat Mulkeen. We will never see the likes of them again.

The tales in this book are a selection of ones that I have heard, and others that I have researched, because my own versions have wandered far from the originals and I needed to pull them back. Most of them I have told in my storytelling evenings.

I hope you enjoy reading these as much as I have enjoyed writing them.

FOLK TALES OF DERRY

1

COLUMCILLE: DOVEOFTHE CHURCHAND FOUNDEROF DERRY

It would be difficult to begin to write anything on the myths and legends of this city, without mentioning its founder Columba – Columcille. He is beloved by all and the people of Derry are rightly proud of him. His presence is remembered everywhere – in the street names, St Columb’s Wells, Columba Terrace and Columcille Court; in the church names St Columb’s Cathedral, St Columba’s church, St Columb’s church; in the naming of one of our most beautiful parks, St Columb’s Park; and, endearingly, in the children’s names, Colm and Columba. So it is fitting that this should be the first story in this book of the folktales of our city and county.

The city itself has been known variously as Daire Calgach, Doire Cholmcille, Derry/Londonderry and even recently as Legenderry.

Tradition suggests that Columcille was the founder of Derry (Anglicised from the Irish Doire, meaning Oak Grove) in August AD 546. Indeed there is a plaque on the wall of the side entrance of St Columba’s church, Long Tower, in Derry that states this fact and inside on the main aisle a white marble stone is embedded which says:

+

SITE OF ALTAR

IN

ST. COLUMCILLE’S

DUBH-REGLES

546-1585

But there is one sure thing about Irish people and that is that they will always find something about which to disagree. And why not disagree about the site of Columba’s monastery? There is a counter claim that his original church was founded where St Augustine’s now stands, beside the Walls of Derry. All I can say is that people will believe what they want to believe and in Derry there is a saying, ‘Why let the truth get in the way of a good story?’

To get back to Columcille, legend has it that he was born in Gartan in Donegal, then he became a student in the monastery at Glasnevin (now in Dublin) and when a terrible plague broke out, the abbot, fearful that his students might contract the Yellow Plague, sent them all back to their homes. It is said that Bishop Etchen of Clonfad ordained Columcille a priest and he made his way to Doire. There, the king offered him some land on which to build his monastery. Columcille refused it at first because he considered it heathen land but accepted it on the condition that he could set fire to it in order to exorcise the pagan ground.

Fire being fire and no respecter of boundaries, it began to creep towards the lovely forest of oaks that Columcille so loved, and the saint fell to his knees to pray that the oaks would be saved. He composed a prayer and, translated from the Latin, it is now known to be the beginning of the superstition that no man, woman or child in Derry would ever be killed by lightning:

Father,

Keep under the tempest and thunder,

Lest we should be shattered by

Thy lightning’s shafts scattered.

Foolhardy young men have been known to run out into a lightning storm, shouting and challenging the lightning to strike. If it ever did, it has not been recorded.

There were also many superstitions about the destruction of oak trees. It was said that an important person who gave orders to have a tree chopped down for firewood died a horrible death and it was called ‘A miracle of Columcille’.

Those who followed him attributed many miraculous cures to Columba, as he was also known, and legends and stories of a Guardian Angel were woven around him.

From Derry, Columba’s light radiated to the far corners of the island, and tradition tells us that he was a great father of the church in Ireland, and that he ranks in importance with Patrick and Brigid. He was a man of learning, a scholar and a scribe, but he was more than that. Legend tells us that he was a son of the soil, born in the country and knowledgeable about country ways, a brother to ordinary men and women. He could cut turf, foot it and stack it, he sowed and harvested crops, fished in rivers, lakes and on the sea, gathered and dried seaweed. When he made mistakes he was open about them and used them to counsel the young.

One of the stories told about him was that as he was dressing he put on one sock and then a shoe, leaving one of his feet naked. Sure, wasn’t that the very time that his enemies crept up on him and he had to run at a great disadvantage with one foot covered and one not? After that it was said that his curse would fall on anyone who dressed in that way. I have my doubts about that one, I must say.

Another curse attributed to him was that if you cut the last sod of turf, danger would follow you. And the origin of this story was that one day he was out at the turf bank, cutting away the sods with the slane and he had just cut the last sod when his enemies (it appears he had a lot of enemies) crept up from behind to attack him. He was unable to escape because, foolishly, he hadn’t left a step up for himself. He’d cut the last step away like the others and he was stuck at the bottom of the bank at their mercy. Luckily, none decided to descend into the trench where Columba stood and they could not reach deep enough to wound him.

Wasn’t he also seen as a prophet who could foretell the future? And there’s quite a few who could quote his prophesies to you to this very day. Unfortunately, with the decline in the native Irish language many of those prophecies are lost or worse, they are of no interest to the present-day Irishman.

Of the stories of his departure from Ireland the one that is most quoted is that of the Brehon Law being invoked, and this is now considered to be the first law of copyright in history. It came about when he copied, without permission, a Latin Psalter that St Finnian of Moville had brought from Rome. When Finnian brought his complaint to the attention of Diarmaid, King of Ireland, the king gave his oft-quoted judgement; ‘To every cow her calf, and to every book its copy.’

Columba, as we know from the stories, had a terrible temper, and when he heard this judgement his anger knew no bounds. He challenged Diarmaid to battle and as he made his way northwards he rallied the men of Ulster and Connacht behind him. At Cul Dreimnhe (Cooldrummon) in AD 561. Columba utterly defeated the king. But when he looked around the battlefield and saw the slain soldiers, bodies heaped upon bodies, he broke down and cried at the terrible loss of life. All told, it was about 13,000 dead, it is said.

In response, Diarmaid called the Synod of Teltown and, to Columba’s great anguish, he was excommunicated, although this decision was later reversed.

But such was Columba’s tortured spirit that he asked his friend from Glasnevin days, St Molaise, to impose a penance upon him. Molaise spoke to him and said that he must be the one to impose his own penance and it should be something very dear to his heart. Only that would bring him peace. Columba pondered on what might be his worst punishment and realised that it would be a fitting penance to leave his beloved Derry of the Oak Groves. So, although he was a stubborn and fiery man by nature, he was also an honourable one and so subjected himself to an exile where he would never again see his beautiful Ireland or step upon her soil.

Were all the tribute of Alba mine,

From its centre to its border,

I would prefer the site of one house

In the middle of fair Derry.

Columba sailed to Iona in a small currach in May AD 563. Before he left he stopped at a rock (now just below the Mercy Convent near Culmore) and took his last look at his beloved Derry. On that rock there are the deep marks of two footprints and one can see the city in the distance. At Shrove Head, the exit from Lough Foyle, he sang his farewell song;

A grey eye looks back to Erin

A grey eye full of tears.

Meanwhile, back in Ireland, the bards were gaining power, much to the concern of the chieftains, so in AD 575, Aedh, the High King of Ireland, called nobles, clerics, poets, storytellers and historians to a convention at the Hill of Mullagh. There he wanted to discuss and clarify and hopefully settle the matter of the power of the Irish bards in the Irish territory of Dalriada and the Scottish Kingdom of Dalriada.

St Columcille was invited to speak on behalf of the bards. It is easy to see how it was a dilemma for him because he had sworn never to see nor set foot on the soil of Ireland again. But legend tells us he found it difficult to refuse the bards. He solved the problem and salved his conscience by being blindfolded and by tying sods of Alba to his feet as he was led into the gathering. That very act made his word honourable and the Drumcait Convention, as it was later called, went down in history as a success.

An old story tells how Viking raiders desecrated Columcille’s grave on Iona. They plundered all of the graves in the cemetery, searching for valuables, since it was the custom to bury items valued in life by the owner with them when they died. Columcille’s coffin was made of fine oak and Mandan the Viking hoped that it would be lined with silver. Not being able to open it there and then, he brought it on board his ship, and when they were far out at sea he opened it. To his great disappointment there was no booty, only the beautifully preserved body of Columcille. In a fit of temper, Mandan closed the coffin and cast it into the sea, where a huge wave carried it away. Eventually, it was washed up on the Irish shore and the peasants who found it brought it to the Abbot of Down. The abbot ordered it to be opened and to his wonder and delight he found that the treasure buried with Colmcille was, in fact, his writings. The abbot was in no doubt that this was the body of Columcille and he ordered it to be buried in the same tomb with St Patrick and St Brigid. This was done with the greatest fervour and reverence by the monks.

One of the clearest examples of the love of Columba for Derry, and the people of Derry’s love for him, is the way he is remembered. On 9 June, his feast day, a congregation gathers at the Long Tower church and the bishop leads a service in the saint’s honour, then a procession of men and women dressed in white robes walk to St Columb’s Well where the water is blessed and ceremonially drunk. The people of Derry traditionally wear an oak leaf in their buttonholes in Columba’s memory.

A stained-glass window on the left side of St Columba’s church, Long Tower, bears the inscription of Columcille’s own words,

Crowded full of heaven’s angels

Is every leaf of the oaks of Derry.

The reason I love Derry is,

For its quietness, for its purity,

And for its crowds of white angels

From the one end to the other.

My Derry, my little oak grove,

My dwelling and my little cell;

O eternal God, in heaven above

Woe be to him who violates it.

2

DERRY’S COATOF ARMS: THE STORY BEHINDTHE SKELETON

The first question that visitors to Derry-Londonderry ask when they see the coat of arms is, ‘Why is there a skeleton on it?’ and that is usually followed by a second question, ‘Who is it?’

Heraldry is history in symbol form and the past history of the area is emblazoned in the coat of arms of the city that joins the St George Cross and the sword of St Paul on the top half. The skeleton and the castle have been variously explained away and many stories have grown up around them.

Some say that the skeleton represents Sir Cahir O’Doherty who held the rank of chieftain of Inishowen from the age of ten all the way down to the reign of James I. He was slain at Doon, near Kilmacrennan, in Tír Chonnail on Holy Thursday in 1607. Others think that the skeleton refers to the starvation experienced during the famous siege of 1688 to 1689.

In fact, the skeleton and the castle quartered on the coat of arms refer to a much earlier date than either of these incidents. In 1305, Richard de Burgo, Earl of Ulster, sometimes referred to as the Red Earl, built Greencastle, which was at that time called Caisleannua, or the New Castle, near Mobyle, Moville. It was later called North Burgh by the Anglo-Normans. North Burgh was a very large building, and Edward Bruce held his court in it in 1316 when he acted as King of Ireland.

From 1310 to 1311, Edward II of England granted Derry-Columcille, Bothmean, Mobyle, (Moville) Fahanmure and portions of Inch to the Red Earl. He occupied this area until his death, when his son, the Dun Earl of Ulster, as he was called, then occupied it. But this Dun Earl had a bitter argument with his cousin Sir Walter de Burgo; it is thought that the argument was over a woman. The Dun Earl seized Walter in a skirmish at Iskeheen, and then imprisoned him in the dungeon where he starved him to death in 1332.

A mark or ring on one of the dungeon’s pillars was supposed to have been made by the ring and chains that fettered him.

The daughter of the Red Earl, having been saved from drowning by this Walter de Burgo, attempted to carry food to him but, being detected, was hurled by her father from the castle walls and dashed to pieces.

The sister of Sir Walter de Burgo greatly resented what the Dun Earl had done to her brother, and encouraged her husband, De Maudeville, who owned extensive territory about Carrickfergus, to avenge her brother’s death. De Maudeville with his men found their opportunity to kill the earl when he was crossing the ford at Belfast, returning from a hunting expedition in Ards in 1333, so his cruelty was avenged.

The death of the Earl of Ulster was the destruction of the Anglo-Norman power in the north of Ireland. The entire estate of the Earl of Ulster was returned to the King of England and remained with him until James I ‘planted’ Derry in 1607 and it was then that the new coat of arms was granted.

THE LEGENDS OFLOUGH FOYLE

3

THE BORROWED LAKE

Long, long ago through the curtain of mist we call Time, there lived two sisters on the western edge of the island of Ireland. There was great jealousy in the oldest sister – some even claim that she was a witch but who is to know? The younger sister was sweet of temper and beautiful of face and loved her older sister. She could refuse her nothing and the witch played upon that loving nature.

Now, the land in the north around the older sister’s abode became dried up and barren and nothing would grow for the sun had parched the land. An unusual happening in the island for this place knew much rain and wind that blew from the great ocean to the west.

The witch connived to get the beautiful lake that her young sister owned near the western shores. Oh, but she was a covetous one and no doubt.

She went to her sister and flattered her about her loveliness and how generous she was and how all the west looked up to her for her sweet nature. The young sister was so delighted that at last her sister seemed to show her affection that she blossomed. She grew even more lovely but didn’t the older witch-like sister’s heart grow darker and blacker and when she’d done enough of the flattery to ask for the lake she sidled up to the young girl one day and said, ‘I would like to borrow your silver lake.’

‘But it is the only water that I have,’ answered the girl, ‘how will I keep my land verdant and fruitful if I have not my lake?’

‘I will return it to you on Dia Luain before the sun sets. Fear not, young sister, would you distrust me so?’

The girl thought for a moment, remembering how sweet her older sister had been recently, and she made up her mind to repay the kindness. She carefully rolled up the lake, but as she gave it to the witch-sister she pleaded, ‘Be careful with my beautiful lough, its sparkle is precious to me. I will wait by the cliffs that fall into the great ocean until I see the ball of fire sink low in the sky. Return my lake on Dé Luain (Monday) before the sun disappears below the dark rim of the earth.’

‘I will,’ promised the witch, and rushed away with the precious lake under her arm.

As the sun began to fall in the sky on the evening of Dé Luain the young girl made her way to the high western cliffs and waited. The setting sun fell lower and lower in the sky and she began to feel anxious.

She called out, ‘My sister, my sister, where are you?’

Just before the sun disappeared into the great darkness, her witch-sister came back empty-handed.

‘Where is my beautiful lake?’ cried the young girl. ‘You promised to bring it back to me.’

‘Alas,’ said the witch; ‘I promised to return it on Dia Luain [Judgement Day] not Dé Luain [Monday]’. It is you who have made the mistake, my dear sister.’

‘Whatever you say to excuse it, you have broken your promise to me.’

‘But promises are made to be broken, my sister. When I laid it like a carpet far to the north, in the in-between land it looked so beautiful. I could not bear to lift it.’

Her young sister’s tears welled up in her eyes and made them shine as bright as the lake she had lost. As the tears ran down her cheeks she begged her sister to return the silver lake that she had borrowed. But, alas, she could not soften the heart of the witch.

And so the lake lay in all its splendour in the north and was given the name Lough Foyle which means the ‘Borrowed Lake’.

On the western limit of the island there lies a barren place blanketed by crisscrossed rocks and beneath that heavy land lies the broken-hearted spirit of a trusting young girl.

4

FEABHAIL MIC LODAINANDTHE ORIGINOF LOUGH FOYLE

If the story of ‘the Borrowed Lake’ isn’t true then perhaps this one is.

Lough Foyle in the Irish language is Loch Feabhail Mic Lodain and that literally means ‘The lough of Feabhail, son of Lodain.’ Now, he was one of the semi-divine people, the Tuatha de Danaan who invaded Ireland, but his magical powers did not save him for he was drowned in the lough and his body was cast ashore.

How he drowned is a bit of a mystery, but the priest and historian Seathrún Céitinn, who lived in the seventeenth century, drew much of his historical knowledge from the Annals of the Four Masters, and in his book the History of Ireland, claimed that eighty-one years after the Tuatha landed on these shores, nine lakes erupted suddenly and burst over the land, and Lough Foyle happened to be one of them.

So the mystery of the origin of Lough Foyle remains. Was it named after Feabhail Mic Lodain who was unlucky enough to be drowned in the flood following the eruption, or did the witch who tricked her sister into parting with it steal it?