11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Glass can add an unusual and ethereal quality to a piece of jewellery. Its transparency, colour and unpredictability make glass a unique material to work with, but it also presents its own challenges. This book introduces the techniques of working with glass to jewellers, and explains how to decide which is the most suitable approach for your design. It covers specific properties of glass, tips for design and ideas for assembling a piece. Hot forming - includes fusing, casting and pate de verre, as well as lampworking. Cold forming - explains how to shape a piece of glass and then bond pieces together Decorative - explains how to embellish your pieces, from painting to photography transfers and metal leaf inclusions. It is a practical guide but, with a wealth of stunning finished pieces, and also provides inspiration for jewellers of all experiences.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 168

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

DESIGNING AND MAKING GLASS JEWELLERY

DESIGNING AND MAKING GLASS JEWELLERY

Mirka Janeckova

First published in 2019 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© Mirka Janečková 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 678 4

Photographs by Mirka Janečková except where specified otherwise

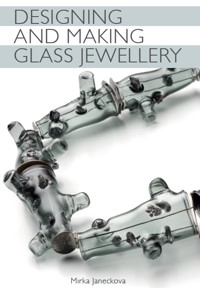

Frontispiece:Glass Drops necklace, Mirka Janečková.

Acknowledgements This book couldn’t have been brought to life without the help of many people. I want to say a big thank you to all the wonderful artists who allowed me to use their images in this book – it would have been a boring book without you! Big thanks to my colleague David Mola for his specialist advice and huge help, especially with explaining copper foil technique. I am grateful to all the people from whom I learned about glass over the years – Petra Hamplová, Martin Rosol, Kristýna Fendrychová, and the teachers and technicians at RCA’s Jewellery & Metals and Glass & Ceramics Departments and the Glass & Ceramic Department at the University of Wolverhampton where I was an Artist in Residence at the time of writing this book. I am very grateful for the awards from the Association of Contemporary Jewellery and the Edinburgh Council, which meant I was able to have dedicated time to explore and write outside my normal working and teaching schedule. Thanks also go to my studio buddy, photographer Brenda Rosette, for helping me with the images.

And special thanks go to all the family and friends who were so patient with me during the writing process.

Photos and sketches in this book are by the author, unless otherwise specified.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

1 GLASS AS A MATERIAL

2 DESIGNING GLASS JEWELLERY

3 HEAT FORMING TECHNIQUES 1: KILNWORKING

4 HEAT FORMING TECHNIQUES 2: LAMPWORKING

5 COLD FORMING TECHNIQUES

6 DECORATIVE TECHNIQUES

FURTHER READING

INDEX

PREFACE

I am a jeweller originally from Czech Republic but now living in Edinburgh, Scotland. When I started my training as a jeweller I was fascinated by the properties of the metals involved and wanted to learn as much as I could about these, but later I wanted to add some different elements to my work. The first material I explored was porcelain: this is an amazing material with huge sculptural possibilities but what I was missing was transparency. I wanted to use material which could transmit the light. I was considering using plastics but they just didn’t feel satisfying and precious enough. So my next choice was glass.

I started to work with glass in jewellery during my MA studies at the Royal College of Art in London. At that point I didn’t know anything about how to work with glass so I searched for guidance in the literature. All the books I was able to find at that time were very technical, not that suitable for jewellery, and it looked as if a lot of strange, expensive equipment was needed to do even basic things. It scared me a bit but eventually I learned how to work with glass with the help of many people and with much of my own experimentation. And I fell in love with this beautiful material. A few years later, I thought that it would make sense to write a book which would help other people to enter the amazing world of glass jewellery and which would be easy to follow and understand – the book which I needed as a student years ago. This is it and I hope you will enjoy it!

Subterranean Rivers, Mirka Janečková. One of my first glass pieces from when I was studying at the Royal College of Art in London: I was experimenting with ways of casting findings such as chains directly in glass.

INTRODUCTION

Glass is a fascinating material which has been part of our material culture for a very long time. It is one of the earliest man-made materials: some sources say that the use of glass by humans dates back over 5,500 years.1 The earliest glass items found were small objects such as beads, amulets and statuettes.

From a jewellery perspective it is very interesting that early makers were using glass to mimic precious and semi-precious stones such as lapis lazuli or turquoise, or even precious metals such as gold. However, at that time, glass was not seen as a cheap substitute but as a material of equal value to the real gemstones. In ancient Egypt the glass was poetically called the ‘stone that flows’ and was seen as a luxury material, evidenced by the fact that most early glass was found in places such as temples, palaces or richly equipped tombs.2

Later, the knowledge of glass forming spread from the ancient kingdoms of what is now called the Middle East to the Roman Empire and then to other parts of Europe – Italy, Germany, Bohemia and as far as Britain and parts of Asia. The use of glass in jewellery has continued uninterrupted until the modern day but has flourished particularly in specific places.

Aventurine Green Glass Bubble Multilink Silver Neckpiece, Charlotte Verity. (Photo: Charlotte Verity)

One famous example is the Italian island of Murano which has been especially well known for its lampworking advancements (among other glassmaking skills) since the thirteenth century CE. The Venetians grouped all their glass manufacture on one island to keep the rest of the city from the potential fire risk but also to protect their advanced glass technology from being stolen and copied.

Another glass jewellery centre in Europe is Northern Bohemia (now Czech Republic), well known for manufacturing glass jewellery and beads from about the eighth century CE. Small seed beads from Bohemian factories have been used in tribal costumes as far away as Africa and North America.

Glass technology has continuously developed and invented; for example, lead glass with its brilliant shine was developed in seventeenth-century Britain. With industrialization in the nineteenth century, glass become more affordable and was not seen as a luxury item any more. Its manufacture spread over the whole of Europe, America and further.

In the twentieth century we can see the renaissance of hand making in the rise of the Studio Craft Movement. Many artist jewellers started to employ glass in their work once again. In this book I will be introducing the contemporary generation of jewellers who are using glass in their work to show the variety of approaches. It is exciting and satisfying to see that glass has been an inspiring material for jewellery artists and craftsmen for thousands of years and continues to be so.

How to Use this Book

My main motivation for writing this book is to make glass techniques available for everyone: for people with no experience of making, for jewellers who want to employ a new material in their practice and for glass makers who want to learn how to use glass as a wearable item. I have done my best to explain all the glass techniques in a way which is easy to follow.

At the beginning of this book you will find out a little about the history and use of glass in jewellery through the ages. Then we look at the different properties of glass: there are various kinds, each of them suitable for a different use. This knowledge can then help you with your design decisions. In the chapter about designing we look at the designing process and the challenges and specifics of using glass for jewellery purposes. This chapter also includes a brief introduction to glass techniques (hot forming, cold forming and decorative techniques). This overview may help you to decide which technique will be the most suitable for your design.

Detailed explanations of glass techniques are discussed in the next few chapters. In the two chapters on hot forming we will look closely at using kiln forming techniques and then go on to lampworking. The cold-working chapter looks at various techniques of shaping glass in its cold form. The final chapter considers ways in which to embellish your pieces. Each technique is explained in words but there are also many photos, illustrations and visual guides.

Card with sample beads from the collection of the Glass and Jewellery Museum in Jablonec nad Nisou, Czech Republic, where costume jewellery making has a very long history.

To really understand jewellery, glass or any making technique it is not enough just to know it in theory. It is a good start, but then it is necessary to start practising and gain direct experience of working with the material. There are two levels of knowledge in the making process: the first is to know something in your head (reading this book will help you with this); then there is ‘the intelligence of your hands’, which is gained only through practice. This applied knowledge requires you to be physically involved in the making process. You need to acquire both levels of understanding to be able to successfully create your pieces.

I would encourage you to try things, keep practising and don’t be discouraged if something doesn’t go well at the beginning. Glass is one of the most beautiful but also the most challenging material I have ever worked with. Once the glass is broken it can’t be ‘fixed’ like, let’s say, metal. When something goes wrong it is usually better to start again from scratch. But the sense of achievement if something goes well is definitely worth all the struggle.

There are so many more exciting glass techniques to be discovered but for the purpose of this book I decided to choose simpler ones and especially the ones which are appropriate for smaller-scale jewellery making. So I will be omitting hot glass and some complex casting techniques as it would be unrealistic for a beginner to use these. If you fall in love with glass (and I am sure you will if you try a few projects), please keep learning and experimenting. I am attaching further literature at the end of this book for your reference.

I hope that this book will be an inspiration and encouragement to all readers.

CHAPTER ONE

GLASS AS A MATERIAL

Glass is a fascinating material unlike any other on earth. It does not fit into any of the three states which we use to describe our material world – solid, liquid or gas. Scientists have had to name a fourth state of matter for glass, calling it ‘supercooled liquid’, which means that glass keeps some properties of its liquid state even when it appears hard.

Science does not qualify glass as a solid because it lacks the crystalline molecule structure which is characteristic of solid objects. The inner molecules of glass are comprised of an open, unstructured and moving matrix. Most solid objects lose their crystalline structure when liquid but regain it when becoming solid but glass is the exception here: it does not have any crystalline structure, either when heated and liquid or when it is in its solid state at room temperature.

Heated glass actually never becomes fully liquid as, let’s say, water. Even when reaching its highest melting point it keeps a toffee-like consistency. At this state, the glass is mouldable and can be used for all heat forming techniques.

Gummy Bears pendants, Emma Gerard. (Photo: Emma Gerard)

Apart from the use of glass as an artistic material, it is widely used in domestic and industrial settings. For example, the ability of glass to transmit light is used in fibre optic broadband conductors, which can transfer information for long distances. Apart from its obvious use in architecture as windows, glass is used as an isolating material in science and medicine, as TV and computer screens or in renewable energies. If you look closely around you, you will find that glass is practically everywhere in the urban environment.

You can find glass appearing in nature too; sometimes these ‘natural’ glasses are sold as gemstones. These can be obsidians, made of rock melted by volcano action (also called ‘volcanic glass’), or fulgurites formed by lightning strikes on deserts or beaches. Another interesting example comes from my home country, Czech Republic, and this is moldavite – an olive green gemstone which was created by the impact of meteorites crashing down on the earth thousands of years ago. These are still found today, often in the river Vltava – hence the name ‘vltavín’ in Czech. The real mineral is relatively rare but there are many fake ones cast from green bottle glass.

Glass has been man-made since ancient times and although the technology has advanced, the basic ingredients are still the same. Glass is made of about 70 per cent silica sand. The finely ground silica is then mixed with additional chemicals, such as soda ash, lime or lead, and heated together. Various oxides can be added to achieve colours. The liquid mass of glass can then be formed into a wide range of forms depending on what is needed – sheet, rods or ingots, for example. We will now look at the various types and properties of glass to help you understand which kind of glass will be the most suitable for your project.

Sketch of molecular structure of glass. Glass has an interesting uneven crystalline structure unlike any other material, which is why it is classified as a ‘glassy’, not as a ‘solid’, state of matter.

Fish brooch by Tomáš Procházka has a body made of Czech moldavite, a stone popular because of its intriguing story of originating from extraterrestrial forces. (Photo: Tomáš Procházka)

Types and Properties of Glass

As we have said, glass is made from heating and fusing silica sand with soda-lime (silica, sodium and calcium oxide), potash, lead, metal oxides or other chemicals. There are countless variations of this recipe, each addition giving the glass different properties, such as hardness, purity, electrical conduction or weight. It is not necessary to know the exact chemical composition of the glass but it is useful to understand which kind of glass is good for certain kinds of work.

Here are the main kind of glasses which are common in artistic practice, divided according to their chemical composition.

Crystal Popcorn Necklace, Petra Hamplová. Beads in this necklace were made by the lampworking technique, using soda-lime clear glass rods. (Photo: Petra Hamplová)

Soda-Lime Glass

This is one of the commonest types of glass and is used for manufacturing glass bottles, tableware and windows. It is suitable for most heat forming or cold forming techniques. There are countless variations in the glass with this composition – each manufacturer would have their own recipe.

Lead Glass

This is sometimes referred to as ‘crystal’ glass. It was invented specifically to maximize the reflection of light and is used whenever you need a great sparkle – for example, cut drinking glasses, chandelier elements, glass beads and crystals. The disadvantage for jewellery use is that the lead content makes this kind of glass a bit heavier.

Borosilica Glass

This is the hardest of the glasses used for artistic work. For this reason it is also used in the industry for making chemical and medical containers, light bulbs and oven-proof dishes. Its high durability gives it an advantage when making jewellery exposed to heavier use, such as bangles or long pendants. The disadvantage is that this kind of glass needs to be heated to very high temperatures to become workable and there is a somewhat limited colour palette compared to other kinds of glass at the moment. However, this situation is changing as manufacturers are bringing new products onto the market all the time.

It is useful to know that there is a wide variety of different shapes and forms of glasses, each of which is good for certain techniques. Glass can take the form of sheets, rods, ingots or smaller decorative elements such as frits and stringers. There are also ‘special’ glasses which have specific optical properties, such as very clear colour effects.

Sheet Glass

This is especially useful for fusing and some cold forming techniques. It comes in different colours, transparencies and surface effects. The sheets are usually sold in flat form, but there are glasses with different patterns available as well.

The most common type of sheet glass is float glass: this is what you would know as ‘window’ glass. The name ‘float’ comes from the way in which this glass is manufactured. The liquid glass mass is poured onto large pans filled with liquid tin; glass ‘floats’ on the tin and later it solidifies and forms the sheet. That is also why window glass has always two different sides – tin and not-tin. Float glass comes in different thicknesses and sizes and is one of the cheapest options for your fusing or slumping projects. However, it is not usually compatible with other kinds of glass.

Sheet glass comes in different thicknesses and a very wide variety of colours. Here you can see 3mm glass sheets with a CEO of 96, ready for fusing.

Glass for Casting

If you want to cast a transparent piece of jewellery then you need a chunk of glass. Glass for casting comes in slab, marble or round ingot form, depending on the producer. For the pâte de verre technique you use a granular glass called ‘frit’.

Various forms of glass ready for casting. For jewellery practice it is helpful to get smaller pieces of ready-crushed glass, otherwise you will have to cut or break bigger slabs yourself.

Rods

Long thin rods are needed for lampworking techniques. They come in various thicknesses from 0.5 to 1mm. Some of them may contain several colours in one rod.

Lampworking rods come in a huge number of shades and effects. They can be transparent or opaque or ‘special’ ones with effects, such as alabaster or metal.

Decorative glass can be used in heat forming processes such as fusing or lampworking, perhaps on the surface of your pieces or as inclusions.

Decorative Glass

There is a very wide selection of decorative glass. Frit is a finely ground glass of various colours or colour combinations; stringers are very thin rods of glass used for decorative stripy surfaces; and confetti is comprised of thin shards of glass. The ancient decorative technique of millefiori (translated poetically as ‘thousand flowers’) is another option: this comes as patterned bead-sized elements with various intricate coloured patterns inside them. These could be traditional flower patterns but also little animals or geometric shapes. You may be familiar with paperweights containing millefiori pieces enclosed in transparent glass form. All these decorative glass elements are particularly suited for fusing and lampworking techniques.

Special Glasses

If you are looking for some more unusual colour effects then you may like dichroic glass. These are glasses which appear to be multi-coloured. They change colour depending on the angle of your view and this effect is enhanced if the glass is used over a black or white background. They are made with a thin film coating technique and there is a variety of different effects available on the market.

Photon Necklace, Yuki Kokai. This necklace was made from a hand-crafted glass rod mounted in 925 silver end caps and chain. The electric blue colour in this glass only appears when it has a dark background; it looks totally clear on a light one. (Photo: Yuki Kokai)