16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

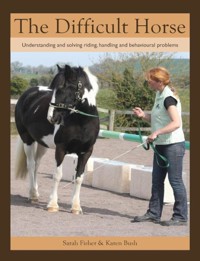

The Difficult Horse provides many insights as to why a horse may develop unwanted behaviours. 'Problem' behaviour is usually more of a problem for the handler than the horse, which is likely to have established patterns of behaviour as a way of helping him feel safe in situations he finds mentally and/or physically stressful. As well as explaining the reasons for a horse's reactive and sometimes dangerous responses, this book suggests a number of practical exercises that can help to address a wide range of commonly encountered issues. Even if you consider your horse to be problem-free, these exercises will still be invaluable in helping you and your horse to develop a closer, more pleasurable and successful relationship.Topics covered include: The causes of stress; Lifestyle and stress management; Reading a horse's 'body language'; Addressing phobias; Uses of TTouch and NLP. An invaluable guide to discussing why a horse may develop unwanted behavioural problems. Suggests practical exercises that can help address a wide range of common issues. Aimed at all horse owners and riding instructors. Superbly illustrated with 120 colour photographs. Sarah Fisher is a TTouch Instructor and animal behaviour counsellor and Karen Bush is a BHS Intermediate Teacher.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 383

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

The Difficult Horse

Understanding and solving riding, handling and behavioural problems

Sarah Fisher & Karen Bush

Copyright

First published in 2012 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book edition first published in 2013

© Sarah Fisher and Karen Bush 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 663 5

All photographs are © Sarah Fisher and Bob Atkins, except those on pages 11 and 23, which are by Bob Atkins, courtesy of Horse & Rider magazine.

Dedication For the Horse, our greatest teacher and valued friend – Sarah For Mum, with thanks for all the encouragement over the years – Karen

Acknowledgements Our thanks go to Linda Tellington Jones, Robyn Hood, Peggy Cummings, Tina Constance, Mags Denness, Shelley Hawkins, Vicki McGarva, Tuesday Lewis, Rachel Denness, Amanda-Jayne Bell and Alison Bridge at Horse & Rider magazine for their help with this book – plus the horses Myrtle, Ginger, Equinox, Panj, Sage, Bailey, Wellington, Toto and Moomin.

Disclaimer The authors and publisher do not accept any responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury, adverse outcome or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it.

Contents

Foreword

I focus on working with the different personalities of each horse I ride, recognising that each one is an individual. I am continuously assessing where each horse’s strengths and weaknesses lie, encouraging them into different outlines to develop correct muscle structure. The neck must be free and supple and the hind legs need to be active. I want the horse to be responsive to a light aid at all times, whether I am asking for an upward or downward transition.

The two basic principles are the same, regardless of the age of the horse or its level of experience – I want him to accept the leg and accept the rein, but I will vary the exercises according to the needs of each horse, as I want him to develop good physical balance and true self-carriage.

By sticking to those two principles, and ensuring that the hands are effective and elastic, the legs are effective and light, and that the aids are consistent, the horse is less confused. Both horse and rider can enjoy their time together, whether out hacking, schooling, jumping or competing in dressage, because the horse is happy and comfortable in his work. Even an Advanced horse may still be fearful of a competition environment, but he can become more confident in his rider and the environment if he understands that the partnership is strong via the correct use of the aids and good training has been established.

The Difficult Horse gives horse owners new ways of understanding the reasons for many unwanted behaviours, but perhaps more importantly it offers simple tools for change that anyone can learn. The aim of this book fits in with my own philosophy and beliefs; that a solid foundation and trust must be in place, that more complex tasks and movements should be developed slowly to ensure that softness and suppleness is maintained, that good balance is essential for physical and mental well being, and that battles can be avoided by going back a step at any stage in training if the horse is struggling with what he is being asked to do.

Lee Pearson CBE Nine times Paralympic Dressage Gold Medallist at Sydney 2000, Athens 2004, Beijing 2008

Introduction

Good horsemanship should look effortless, with horse and rider working in harmony to create a perfect partnership that is a pleasure to watch and a rewarding experience for both parties. This same principle should apply to all aspects of horse management.

Many problems occur because early warning signs that the horse was struggling were overlooked or ignored, or foundation steps in handling and training were rushed or not put in place at all. All horses benefit from a calm and quiet approach, but as unwanted behaviours begin to develop or become increasingly difficult to manage, our own fears and concerns can trigger more forceful handling. This in turn exacerbates the stress that the horse is already under, giving rise to more volatile reactions and the creation of new and more dangerous behaviours. It is this lack of understanding that causes the relationship between horse and man to break down, and compromises the horse’s natural willingness to be a co-operative partner. As Xenophon stated so wisely in 400BC: ‘Where knowledge ends, violence begins.’

There is always a reason for unwanted behaviour. The skill comes not in relying on force to push the horse through his difficulties, but in understanding the motive for that behaviour, and learning kind and effective techniques to help address his concerns. A horse that is able to think and to move freely through the body will be safer and easier to handle and ride than a horse that is stressed and/or physically compromised through ill-fitting equipment, inappropriate training and poor posture. Even if he lacks education, a horse that is calm is able to process and retain new information more easily than a horse that is tense, enabling you to work on advancing his skills rather than simply doing your best to work around or manage behavioural concerns on a daily basis.

Take time to observe your horse and understand his body language.

Horses, like humans, have different personalities and different capabilities. Taking time to observe your horse and to learn how he uses his body language to communicate with you will help you to take any necessary steps to ensure that he is happy and comfortable in every aspect of his life.

There is always a reason for unwanted behaviour; the owner needs to learn kind and effective techniques to address the horse’s concerns.

When working through a problem remember that all behaviours are connected. For example, a horse that always carries himself in a high-headed frame may find it hard to stand still for the farrier, may move off at the mounting block the moment your foot is in the stirrup, and spook, spin or nap when ridden. He may also be difficult to handle from the ground. Teaching your horse to lower his head and release his top line, and learning exercises that you can do in the stable, in hand and under saddle that will strengthen his back, enabling him to work more efficiently and effectively, will go a long way to helping you address all the connected and unwanted behaviours. You may need to adapt the way you ride, manage and care for your horse, as there may be several contributory factors such as poor dentition, saddle fit and foot balance – but with increased knowledge you can help him reach his full potential whether you want a horse that is a pleasure to hack out in open countryside, or have more ambitious goals for yourself and your equine friend.

Key to Exercises

As well as suggesting specific exercises for particular problems, the reader is also referred to other exercises that might also be helpful. Below is an alphabetical list of the exercises given in this book, with the name of the problem opposite, where it is explained. We hope this will enable the reader to find these cross-referred exercises quickly and easily.

For example, in the problem ‘Girthing issues’ the exercise ‘Belly Lifts’ is given as helpful, and it is also suggested that the reader might try the exercise ‘Lick of the Cow’s Tongue’: to find this exercise, locate it in the alphabetical list below, see which problem it is contained in, then locate that problem – most are in Part 3, the A–Z Directory. (The problems in the A–Z Directory are also listed alphabetically.)

PART 1

IDENTIFYING PROBLEMS

1 Understanding the Equine Character

So what is a ‘problem’, and why do ‘problems’ arise? A ‘problem’ may be a minor irritation which inconveniences you, or something which prevents you from achieving certain goals – or it could be a serious behaviour that puts lives at risk.

From your horse’s point of view, his actions may be a perfectly sensible response to a situation he finds himself in. The fact that they cause difficulties for you isn’t his fault, and may not be yours either; but it is your responsibility as owner or carer to try to understand why he behaves as he does, and to help him learn how to cope with things he finds challenging in a way which is acceptable and safe for both of you. Failure to do so may lead to an escalation of his misbehaviour, and will certainly make it difficult for you to develop a true partnership.

Horses are not difficult on purpose: they do not intentionally set out to annoy us. On the contrary, the fact that they allow us to climb on their backs at all, let alone perform the physically and psychologically demanding tasks we ask of them, is a testament to their willingness and desire to co-operate as much as to their courage.

If you encounter any difficulties it is therefore important to consider all possible reasons for them; furthermore, as well as involving a certain amount of honest and objective self-assessment, it’s also helpful to have a basic understanding of what makes your horse tick, both as an equine and as an individual.

UNDERSTANDING THE HORSE’S SURVIVAL TRAITS

Like dogs, the modern-day horse is a product of human intervention as well as of evolution, with intensive breeding for specific qualities giving rise to a whole range of different breeds. But horses have changed far less than our canine friends, partly because they have only been domesticated for around five to six thousand years as compared to around thirty thousand for dogs, and have not been subject to such constant and close human companionship.

It is also due to the fact that so many of the physical and behavioural traits which originally helped the horse survive – such as his sensitivity, being quick to react, co-operative, and able to gallop and jump – are also a key part of what makes him so good at the things we want to do with him. On the whole, horses cope remarkably well with the challenges of the modern-day environment, but domestication can sometimes be a thin veneer, and the very characteristics which make him so suited to our purposes can also underlie behaviours we consider undesirable.

Instinctive Responses

The horse’s instinctive responses might be described as the five ‘F’s: flight, fight, freeze, faint and fool around. Regardless of where an animal is on the food chain, the majority of animals prefer to respond to fear by running away. It is not conducive to survival to engage in conflict, since the risk of injury and even death is increased through fighting. Only if the ability to flee is inhibited for any reason will the majority of animals, including people, either go into ‘freeze’ or respond with displays of aggression (fight).

When a horse is in ‘freeze’ his head will be raised, his nostrils may be flared and his eyes will be wide. You may also notice that his heart rate is elevated and his body is tense. Trying to push or beat a horse out of freeze can lead to an explosive reaction, risking injury to both horse and handler. It is far safer, as well as kinder, to encourage him to move a little by stroking along the lead line (or one rein if you are mounted) so as to gently turn his head, or to lower his head without forcing it down (see Exercise ‘Stroking the Reins’ – seeKey to Exercises). He will probably jog or move off a little sharply for the first few strides and may go back into freeze after a couple of steps, but if you stay calm, and keep encouraging him to release through his body with your hands and/or your own body, he will recover more quickly.

A horse that is defensive in his behaviour is not being ‘dominant’, but is under duress and communicating high levels of concern. If pushed, he may ‘faint’. This fear response can be triggered by forceful handling – when loading, for example – and some people sadly believe that the horse is lying down because he ‘knows’ that by dropping to the floor he cannot be forced into the lorry. ‘Faint’ is an indicator of extreme levels of stress, and no horse should ever be pushed to this point.

‘Fool around’ is often misinterpreted as the horse being ‘naughty’ or lacking focus. The horse may grab the lead line, toss his head around, paw the ground, fidget and so on. It is usually triggered by confusion because the horse is struggling with the situation, but it can be due to anticipation of something either pleasurable or worrying, and is often accompanied by areas of tension through the body. Even if, for example, your horse is working well initially or is enjoying being groomed, if he starts to fool around, stop what you are doing. You may have worked him for too long – even though you may have considered the session brief – or have touched a sensitive area, or he may have become distracted because he did not understand what was being asked of him. Look for the pattern: there will be one, and by noting when and why your horse starts to lose focus or change his behaviour, you can make any necessary alterations to the way you handle and train him.

Physical Senses

Modern-day horses may not look much like their distant ancestors, but their senses – vision, hearing, taste and smell, and touch – remain much the same, and are designed to aid in survival. The way a horse perceives the world around him can differ slightly from the way in which we do, and may affect his response to the environments and situations he finds himself in.

Vision

Eyesight is one of the horse’s most important senses with regard to warning of potential danger. The positioning of the eyes to the side of the head provides good all-round vision – about 350 degrees, with ‘blind spots’ created by the head and body just in front, at the back of the head, and immediately to the rear – hence the advice always to approach from the side, so as to avoid startling him.

If something seen with one eye catches the horse’s attention, by turning his head to look at it he can use binocular vision (both eyes at the same time), which improves his depth perception. But once the object is within three or four feet, the length of his nose begins to obscure it, and to continue looking at it he needs to turn his head again and observe with one eye. Visual information can be transferred from one eye to the other: nevertheless, it is often noticed that a horse will spook at an object he has already seen when passing it for the first time in the opposite direction and seeing it with the other eye.

Horses are very sensitive to movement – not just of people, animals and inanimate objects, but also of shadows moving on the ground or light reflected from the surface of water. The ability to detect motion is greater in their peripheral vision, and this, combined with a reduced ability to see in detail in this area and the wide field of vision, can explain why horses may sometimes appear to spook at nothing.

Although better than us at seeing in low light conditions, horses’ eyes adjust less quickly to abrupt changes, which is why they may be reluctant to enter a dark stable or trailer, or may refuse at a show jump or cross-country fence positioned in a shady area.

Some individuals may be long- or short-sighted, and as with humans, ageing can lead to a deterioration in eyesight. The gradual loss of sight in one eye is generally coped with well – often so well that the owner doesn’t realize a problem exists. Given time and good care, some horses even learn to manage well with a loss of sight in both eyes. However, horses with poor vision may be more noise-sensitive, and anyway care must also be taken to warn them of your approach through the use of your voice.

When riding, the horse’s head carriage can also affect vision; when asked to work in an outline it can limit what he is able to see ahead, in the same way as your own vision is inhibited if you look downwards. If he is overbent, it decreases still more. For a horse, working in an outline requires not just correct training of his physique, but that he places great trust in the rider to keep him safe, both from possible predators and from bumping into anything.

Hearing

Our own hearing range is around 20Hz–20kHz, and that of a horse is around 55Hz–33kHz: this means that he can hear some high-pitched sounds that we can’t, but not some of the lower frequency ones. For example, depending on how close and loud it is, he may be able to hear, and be disturbed by, ultrasonic rodent repellers if you use this form of pest control.

Each ear can be rotated to give all-round hearing without having to move the head, and its funnel shape helps in focusing on a particular sound, just as you might cup a hand round your own ear to shut out extraneous noise to help you hear what someone is saying.

Music is often played on yards, and studies have shown that it can be beneficial in reducing stress in elephants in zoos, soothing dogs in rescue shelters, and calming newly weaned foals. But avoid leaving radios on constantly, and choose the sort of music which horses show definite preferences for – rhythmic and calming instrumental melodies. Consider volume as well: sounds can be muffled to a certain extent by pinning the ears back, but can’t be shut out altogether.

Some individuals appear more reactive to sound than others, but sudden noises can startle any horse – not just extra loud ones such as fireworks, shotguns and bird scarers, but dropped mucking-out tools and slammed doors too, which can contribute to raising a horse’s stress levels. Noises which he finds worrying or irritating, but which he can’t identify, may also cause increasing anxiety. Adrenalin can increase noise sensitivity, and a horse that is stressed will be more reactive to sound.

Equine sensitivity to sound can be usefully employed: for example, a low-pitched, soothing tone with long drawn-out syllables can have a calming, steadying effect – although bear in mind that shouting and high-pitched tones can have the opposite result. Talking while working around your horse will ensure that he knows where you are at all times if you move into a ‘blind spot’ or if he has vision issues, and when approaching him this can also be a more reliable form of identification for him than your appearance or smell, both of which can change from day to day (and even during it) depending on what deodorants, scents, aftershaves and soaps you use and what clothes you take off or put on.

As with vision, hearing can deteriorate with age, or be compromised by health issues. Never trim the hairs inside the ears, as they have a sensory function and help keep out dirt and flies. Note whether an ear is flicked towards the source of a sound: reduced or loss of hearing will affect his ability to respond to verbal cues, and may cause him to be more easily startled by anything approaching from the rear.

Taste and Smell

Taste and smell are very closely linked: they are well developed senses which, together with mobile lips, enable horses to differentiate between different foodstuffs, and to reject those which are unpalatable. Smells can be detected over far greater distances than humans are capable of, and with considerably greater acuity; scent recognition plays an important role in greeting and identifying other horses – for example between mares and foals – and in detecting possible threats. Strange, strong or unusual smells can cause alarm, where the horse is reluctant to approach the source of the smell, while a change of feedstuff or drinking water, or the addition of supplements or medications, may lead to the horse refusing to eat or drink.

Can horses smell fear? Although nervousness is also betrayed by body language, it is quite possible that chemicals produced and emanated by the body in response to stress can be detected. As with hearing, stressed horses are likely to have an increased sense of smell.

Touch

Horses are highly sensitive to touch, able to detect as tiny and light a thing as a fly landing on them, and to twitch the skin to dislodge it; some areas of the body are more sensitive than others – the flanks, beneath the belly and between the thighs, for example.

They enjoy having certain areas scratched with the fingertips, and field companions can often be observed enjoying mutual grooming sessions. When using touch as a form of praise and reward, stroking and scratching is preferred to patting, which can seem abrupt and may be perceived as a punishing action.

The long whiskers on the head also function as sensory organs: deeply embedded in the skin, each is rooted in a specialized follicle with a rich supply of nerves. These help foals locate the teat when suckling, they aid grazing by determining the length of grass and proximity of the ground, and help prevent facial damage by warning of nearby objects; it has even been suggested that they may be able to detect sound and vibrations. Although little research has been done with regard to horses, these whiskers – or ‘vibrissae’ – have been shown to be sufficiently important as a sensory organ in other animals that trimming them has been banned in Germany.

2 Investigating Problems

Behavioural problems in horses can have various underlying causes; these might include the effects of stress, the influence of genetics (inherited behavioural traits), physical problems, or previous experiences.

THE UNDERLYING CAUSES OF UNDESIRABLE BEHAVIOURS

Stress

Stress, both physical and psychological, can be a major cause of undesirable behaviours. The relatively short amount of time the horse has been domesticated has done little to equip him for the modern world and the increasingly artificial environments in which he is kept today.

Individual horses react differently to stressful situations, with some coping better than others, depending on factors such as temperament and previous experience. Where stress is ongoing as opposed to an isolated event, the constant release of the stress hormones which prepare the body for action can have an adverse effect on health. As well as increasing the risk of colic, gastric ulcers, laminitis and diarrhoea, they can inhibit the immune system and growth, reduce reproductive capacity, affect bone integrity and hoof growth, and may lead to the appearance of stereotypies such as crib biting and weaving, and behaviours such as spookiness. Common stressors and stress management are discussed in more detail in Part 2.

Inherited Behavioural Traits

Just as physical characteristics can be inherited, so can behavioural traits. They can be breed related, and/or passed on through family bloodlines – though it is important not to tar all horses with the same brush. It is easy to develop subconscious prejudices based on previous experiences and popular mythology, and these can often be unfounded. Yes, temperamental chestnuts, flighty Arabs and lazy, unflappable cobs do exist – but there are just as many placid chestnuts, laid-back Arabs and reactive cobs, so it’s important to view each and every horse as an individual.

Bear in mind also that environment, handling and training each play a critical role in how a horse behaves, and where less desirable traits such as fearfulness, reactivity or a predisposition to various stereotypies have been inherited, they become even more important in helping the horse to develop into a balanced personality.

Physical Problems

An out-of-character behaviour can often be due to physical discomfort, especially if it appears suddenly; where low-grade pain is concerned, behaviours can be slower to develop and a link between the two may be less obvious. Horses also have varying pain thresholds, so what can be borne by one may be intolerable for another.

As a first step in tackling undesirable behaviours, always ask a vet to check for any physical problems so that health issues can be remedied or eliminated as a cause. Even if nothing is found, don’t rule it out completely but continue to monitor and observe closely, as getting to the root of health issues is not always straightforward; some ailments can be difficult to diagnose, and you may have nothing more than intuition to guide you. Be prepared to ask for referrals and further tests if necessary – this can be a time when you will be grateful that your horse is insured.

Although an improvement may be noticed, removal of the source of the discomfort does not always lead to the immediate resolution of a problem, as the horse may still anticipate, or make associations with pain which can take time to change.

Horses were never designed to be ridden; the spine and associated musculature is intended to help suspend the large and bulky belly, not to support the weight of a rider or to sustain the exaggerated athletic efforts and way of moving that we demand. The spine is not the only part of the body that can feel the strain, so as well as constant observation and awareness of changes in movement, willingness, temperament, posture and general appearance that may indicate physical health issues, a case could be made for preventive health care, with physiotherapy and other modalities being usefully employed for the maintenance of physical wellbeing, and not just when a problem is suspected.

Early experiences both good and bad will influence how the horse matures – forceful handling of a youngster can trigger defensive responses. Long schooling sticks are ideal for initiating contact with any horses that are threatened by the presence of humans as they enable you to keep a distance and allow the horse to move away if necessary.

Previous Experiences

Horses have good memories, and can form deep and lasting associations, particularly for traumatic events. Even when the cause of an unpleasant experience has been removed, the horse may continue to anticipate it for a long time to come – for example, continuing to spook at a certain point on a ride where a bag flapped across the road and scared him, or to flinch, pull faces or nip when being saddled if it has previously been a source of pain.

Likewise, lack of experience can predispose to difficulties too: horses that have been kept in relatively isolated circumstances, or were orphaned or weaned early, are more likely to be fearful and to exhibit unwanted behaviours. Over-handling orphaned youngsters, particularly if they have grown up without the company of another youngster in their early years, can give rise to extremely dangerous behaviours as they mature.

If early signs of concern are ignored when the horse is touched on specific parts of the body he has no choice but to increase his body language. Punishing the horse for his reactions reinforces his anxieties, breaks down the relationship and is likely to trigger more volatile outbursts.

Although they may be more settled and established in their behaviour, older as well as young horses can be adversely affected by negative experiences – though remember that it is also possible to provide positive experiences, producing changes in behaviour for the better.

RESOLVING PROBLEMS

Do all problems need resolving? Equally, is it possible to resolve all problems? And should you give up on a problem, or persevere at all costs? The answer to each of these questions is both yes and no, and depends on a number of factors.

Warning Signs

Some behaviours may not directly affect you, or may be sufficiently minor that it is easy to overlook and live with them. But any atypical behaviour can be an indicator that all is not well in your horse’s world, so every effort should be made to discover and remedy the cause. Failure to do so will affect your horse’s quality of life, may affect his health and performance, and could lead to more serious developments – many major behavioural problems can trace their origins back to seemingly small and trivial beginnings.

Achieving Success

Can all problems be cured? It may be possible to resolve some problems so successfully that they don’t occur again, but this isn’t always the case, and you should be realistic about how much change you can achieve. It may only be possible to partially remedy some undesirable behaviours, and others may prove impossible, depending on a variety of factors; these might include:

The nature of the problemHow long it has been in existence – the more ingrained a behaviour is, the longer it may take to remedy it, and the more difficult this may beYour expertise and skillHow feasible it is to make changes to the environment and managementThe presence of any ongoing physical trauma or health issuesStereotypies such as box walking, weaving, cribbing and windsucking can often prove particularly troublesome to eliminate, and may sometimes continue even when the underlying cause has been dealt with. These behaviours trigger the release of ‘feel-good’ chemicals in the brain, and it is thought that consequently there can be an element of addiction involved. But as any smoker trying to quit the habit will tell you, it is not just about chemicals – established habit can play a part, too.

Sometimes horses will revert to behaviours you thought had been ‘cured’ when placed under pressure or stressed, so it may be necessary not just to change the environment and daily care, but to rethink the work the horse is asked to do.

Working Through a Problem

Sometimes you may need to decide whether it would be best to give up on a problem, rather than persevering at all costs. While working through and resolving difficulties can be an immensely rewarding process, which can lead to the forging of close bonds between you and your horse, in some instances it may not always be feasible or safe for you to do so.

Much depends on the nature of the problem, whether you are skilled enough to deal with it, or are able to find expert help, and have the time available both to work on the problem and to wait until it has sufficiently improved to a level where you are satisfied. Finances can also be an aspect: some problems may be expensive to resolve.

If a behaviour has eroded your nerve, even after it has to all intents and purposes been resolved, you may continue to experience feelings of anxiety. Although modalities such as TellingtonTouch (TTEAM) and Neuro Linguistic Programming (NLP) can be brilliant in helping to develop confidence and restore damaged trust, sometimes a change of owner is the best solution for everyone. Persisting when intuition and common sense tell you it isn’t something you feel comfortable doing may lead to another hiatus, and one which may have more serious consequences. However, do not pass on a problem without telling a potential buyer about it – and for your horse’s sake be very careful about any choice of new home.

Professional Assistance

At what point should you consider getting professional help? Never battle on alone if you are struggling to cope, or failing to make any headway in resolving a problem, or if it is becoming worse. There is nothing wrong about admitting that you don’t feel knowledgeable or able enough, or are too nervous to deal with a problem by yourself. Seeking out expert and competent help is the sensible course of action!

Sometimes you may find that several people come forward willing to offer advice – but be careful about which to accept: even ‘experienced’ people aren’t necessarily knowledgeable, and those who subscribe to dangerous, inhumane or outmoded practices are definitely to be avoided. This isn’t always as easy as it sounds, especially when the person offering the advice has perceived status and acceptance, and you may need to resist well meaning but not always well informed pressure from friends and acquaintances, for your own and your horse’s wellbeing.

Flexibility, adaptability, open-mindedness and a willingness to try different approaches are important, but any advice or training method you follow must suit both you and your horse: it must be humane, and must absolutely avoid any bullying, coercive techniques.

Just as important as training methods, you need to trust and feel comfortable with the trainer, too: no matter how good they may be, if there is any kind of personality conflict you will not get the best result. Sometimes people have an aversion to a certain breed, type, colour or sex of horse, and this can lead to a certain rigidity of thinking and consequently poor handling or inappropriate training techniques. Empathy with you and your horse is vital, and a trainer needs to be able to communicate well with both of you, and to show you how to replicate the work he or she does, rather than keep it a jealously guarded secret.

Finding the right advice may take time: if necessary give your horse a holiday while you search for it. Whether you find someone through personal recommendation, advertisement, Yellow Pages or online, don’t engage their services until you have first discussed your problem, asked how they intend to work through it, investigated the likely outcome, found out how much all this is going to cost you, and in particular have watched them at work with other horses and riders, because what people say is not always what they do.

Obviously it is more convenient for everyone – and will be cheaper, too – if you can find someone reasonably local; but if you can’t find the right person on your doorstep, be prepared either to travel to them, or to pay for them to come to you.

Enlist the help of someone who can help you with your horse, but make sure that it is someone who will hear you and work with you, rather than trying to ram their own opinions down your throat. You should feel supported and inspired by any person who helps you, and not be made to feel intimidated or fearful in any way.

Don’t Blame Yourself!

No one becomes an expert overnight: on your journey to becoming a knowledgeable and experienced horseperson, it is inevitable that you will make some errors – although it is to be hoped that you won’t make too many, or of too serious a nature. Sometimes problems are not of your making, but inherited from previous owners.

If your horse does develop a problematic behaviour it is important not to go on a guilt trip about it: rather, award yourself a pat on the back for noticing it, and deciding to do something positive about it. Feeling excessively guilty or sorry for the horse can inhibit the growth of a balanced relationship between you, and is likely to interfere with your ability to make the right decisions and take the correct actions.

PART 2

PROBLEM SOLVING

3 Understanding Horse Behaviour

Labels are given to equine behaviour as a way of identifying various issues, but this can limit our ability to help the horse, as they can cause us to overlook the reasons why the behaviour became established in the first place.

Two labels commonly used (and frequently incorrectly applied) by many trainers and owners with regard to behaviour are ‘submissive’ or ‘dominant’. These labels can be misleading, and certainly when it comes to ‘dominant’ behaviour, can trigger inappropriate handling and unsuccessful behaviour modification techniques which not only break down the equine/human bond, but fail to address the underlying reasons that caused the more dominant behaviour to manifest itself in the first place.

In terms of behaviour, the true application of the word ‘dominant’ should be to describe a very specific behaviour around a resource – such as food for example – when another being or beings are present. ‘Dominant’ should never be used to describe a personality, and even if the word is being correctly used in the right context, our own perception of that behaviour may be incorrect. For example, a horse which expresses what we may view as aggressive behaviour around food may in fact be sore in the mouth, suffer from gut problems, or be stiff and therefore less mobile when grazing or eating hay in the field. If the horse has been stabled for long periods of time and subjected to poor management and an inappropriate feeding schedule, he may have learnt to become more protective and reactive around his feed, which has become the highlight of his day. If he experiences any stress or discomfort when being groomed, tacked up or ridden, his hostile response to you approaching him in the field or stable may in fact be linked to a negative association with you, rather than an aggressive action intended to keep you away from his food.

Once applied, labels also tend to focus attention on that particular issue, with other, less obvious ones, which may overlap, going unnoticed or ignored, while positive and appropriate behaviours may be overlooked and go unrewarded, which seriously limits the possibility for change. Another drawback with labels is that they tend to stick and can be difficult to remove, influencing all future work with the horse.

THE BEHAVIOUR SPECTRUM

In order for us to develop appropriate and successful strategies to help horses, it can be more beneficial to look at behaviour in a different way.

First, to take the earlier example, how about replacing the words ‘dominant’ and ‘submissive’ with ‘extrovert’ and ‘introvert’ instead? This immediately changes the way in which you view the behaviour, and a rather black and white image is replaced with one which is open to a wider variety of interpretations and doesn’t conjure up images of violence and subjugation which will invariably colour your response. Bear in mind we are talking about behaviour at this point, not trying to establish whether a horse is introvert or extrovert in his nature.

The behaviour spectrum.

Secondly, few horses remain in one state all of the time. Behaviour is not fixed, but in a state of constant change from minute to minute, and day to day. Understanding that behaviour is a continuum and not fixed can open our eyes to seeing horses in a new way, and help us understand how we can use the many tools at our disposal to bring each horse into a better state of emotional and mental balance. If we think of extreme introvert behaviour as being at one end of a spectrum, with extreme extrovert behaviour at the other, we can see that most horses (and people) are generally continuously moving through that spectrum to some degree, depending on many factors including the current environment, interaction with other horses and people, diet, training techniques and so on.

For further clarity, let’s apply colour to that spectrum: at one point on the scale the colour is dark blue (excessively introvert), and at another it is orange (excessively extrovert). If you consider this spectrum as a circle rather than as a straight line it will also serve as a reminder that the horse can move from one extreme state to another in either direction, or even directly across the diameter of the circle, without necessarily moving through the entire colour range first. When moving around the circle you’ll notice that the colours merge into each other with no obvious definitions between each shade, just as there are often no clear boundaries or beginnings and endings between behaviours.

The balance point can be placed at the centre of a horizontal line drawn across the circle. A horse which is well balanced in temperament will be in, or close to, that middle point, although he will still continue to move through the spectrum according to the influence of a variety of factors. These factors will also dictate to a degree both how far and how quickly he moves, and whether he is able to return to a more balanced state or not.

A horse that we would generally consider to be in balance would be able to move effortlessly through these phases without the need for much intervention from his owner or carer. For example, there will be times when a horse is exuberant and joyful, such as when he is first turned out, but also times when he may be hesitant, such as going into a horsebox or when approached by a vet. He may be active when ridden (extrovert), but peaceful and calm in his stable (introvert).

Most horses, like people, will of course have a tendency to be naturally more introvert or extrovert in character and therefore behaviour, but problems tend to arise when the horse is stuck in one phase and has moved, or is moving, further away from the point of balance in the spectrum. If this occurs or has occurred in the past we may see more obvious signs of imbalance.

These examples of extrovert and introvert attributes are by no means comprehensive, and are not necessarily exclusive to either behaviour or phase. They are intended merely as a guide to help you adopt an observant and flexible approach, and to enable you to start thinking about what sort of work and training techniques may be most useful to bring your horse into a better balance.

Always remember that behaviours overlap and merge, and that any experience the horse has can drive him in one direction or the other, regardless of the starting point within the spectrum. For example, quiet horses are often ‘pushed’ too quickly, and one which is naturally more introvert may be forced to become more outwardly reactive in order to make his fear or confusion known. Similarly, a naturally outgoing and tactile horse subjected to forceful handling and aversive training techniques in a bid to curb his exuberant behaviour may shut down and become withdrawn as a result.

Looking at behaviour in this way will help you to understand that the horse is not necessarily making deliberate choices about how he responds to the environment that humans have created for him. We would encourage you all to start making notes about how the horses that you work with and/or own respond to a variety of situations. As already explained, ideally you should see a mix of both introvert and extrovert behaviours, depending on circumstance and even the time of the day. Begin trying to develop or think of strategies that can help you have a positive influence on the behaviour that you see at the time.