32,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

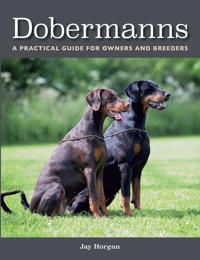

As a breed, Dobermanns have acquired an unjustified reputation as 'devil dogs' due to their courage, loyalty, intelligence and physical strength. This book aims to dispel the myths surrounding this magnificent dog, and shows how Dobermanns can be loving and gentle family pets, as well as their more traditional role as guard dogs. Dobermanns - a practical guide for owners and breeders traces the development of the breed from its early beginnings in the nineteenth century through to the present day, and offers the reader advice on every aspect of rearing and caring for these beautiful dogs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Dobermanns

A PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR OWNERS AND BREEDERS

Jay Horgan

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2017 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2017

© Jay Horgan 2017

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 309 7

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

1The History of the Breed

2The Dobermann in Great Britain and Ireland

3Character and Temperament

4Choosing a Breeder and Buying a Dobermann

5Bringing Your New Puppy Home and the First Year

6Working and Training the Dobermann

7Conditioning and Exercise

8Nutrition and Feeding

9Breed-specific Healthcare

10General Health and Welfare

11The Breed Standard

12Showing the Dobermann

13Judging the Dobermann

14Breeding, Pregnancy, Whelping and Rearing

15The Stud Dog

16Genetics

Glossary

Further Information

Recommended Reading

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My gratitude to the many people who helped me with this book. I am indebted to all the photographers and people who donated images of their beloved dogs, which have been invaluable. The people who donated images of their beloved dogs have been invaluable to the success of the book, as have the friends who proofread the chapters for me. I have made every effort to be as accurate as possible, but inevitably there will be some errors which I hope you will forgive.

I am deeply indebted to my husband Martin, without whose support and indulgence I could not have had the time or resources to complete this task.

As any owner will tell you, the Dobermann is unique and I am lucky to share my life with all the great dogs we have owned who have taught me so much. I cannot imagine life without a Dobermann by my side.

1THE HISTORY OF THE BREED

The Dobermann is by nature a protector, guardian and companion. Kept in a home and in intimate touch with people, he will display his inherently watchful, willing, obedient and brave character.

Phillip Gruenig

The Dobermann began life in Apolda, Thüringen, in central Germany in the late 1800s. Much of its history is based on hearsay and conjecture, which in part adds a touch of mystery and intrigue to the breed. The breed was named after its original creator Karl Louis Friedrich Dobermann, who was born in Apolda on 2 January 1834, where he remained resident until his death on 9 January 1884, at fifty years old.

During his lifetime Herr Dobermann had a variety of occupations, including working in the slaughterhouse as a skinner, being the local dog catcher, and some say acting as a police officer in the evening hours; but his most famous role was as municipal tax collector for the Niederrossla-Apolda Chamber of Accounts. This was as unpopular a role then as it is today, and necessitated having a dog by his side that would be a disincentive to anyone who might cause him trouble on his rounds. In 1870 he owned such a dog, called Schnupp, described as a black male with red markings and a grey undercoat. (Schnuppe/Schnupps/Schnuppine was a very common name for dogs at that time, meaning grey.)

Although the dog seen at Herr Dobermann’s feet was apparently this dog Schnupp, it was not the dog used in his breeding foundation, as it was castrated at nine months. Schnupp was remembered by Herr Dobermann’s son, Unser Louis Dobermann, as ‘a dog of such great intelligence as is seldom found. He was clever and fearless and knew how to bite. My father could not have chosen a better one.’

Dog breeding was very popular throughout Germany, and particularly in the Apolda region at that time. An annual dog market was held there at Whitsuntide from 1860, when about a hundred or more dogs would be on sale and on show, and would attract many buyers and sellers of dogs. Dogs would be classified as hunting breeds, butcher’s dogs, ratters and terriers, guard dogs and small toy luxury dogs, and others. This market also included food stalls and music, and it became such an important event that it is officially recorded in the history of the city of Apolda.

The only known photograph of Herr Dobermann with friends and dogs.

Market square in Apolda with a sculpture of Dobermanns.

Herr Dobermann was a regular visitor to this dog market, because with his various occupations it provided him with the ideal opportunity to select dogs with the physique and character that particularly interested him for his breeding plans. From the outset his motivation was to breed dogs not just for the sake of it: his intention was to breed a dog that would be capable of reproducing itself – to create a new and particular breed.

In the early days of his ambitions he could only breed the occasional litter as his homes were too small to cope with the larger scale plans that he had; but in 1880 he finally moved to large enough premises to breed more litters. In the meantime he was fortunate to have had two colleagues, night-watchman Herr Rabel and Herr Stegmann, who were eager to join him in his plans for the breed, and with whom he was able to place stud dogs and breeding bitches.

EARLY INFLUENCES

Herr Dobermann’s vision was of a large, terrier-type dog, sturdy but agile, with a sharp mind – and most importantly it had to be an unparalleled personal guard dog of fearsome reputation. With the sources available to him, and with a selection of various dogs from other breeds in the region, he began to breed his ideal dog. This part of the history of the Dobermann is open to speculation, as no breeding records were kept; consequently disagreement has always existed over the original types of dog used to create the breed.

Trying to place ‘Dobermann’s dogs’ into any category at this time is quite impossible, as they were wholly different from the Dobermann of today. They were short (35–40cm/14–16in) and squat, and appeared more terrier-like than anything else. The consensus of opinion is that up to the first half of the 1900s the probable originators of the breed were a type of dog predominant in the region colloquially known as the ‘German butcher’s dog’, the Thüringian Shepherd (a smaller herding breed than the model of the breed that we know today), the Thüringian (German) Pinscher, and the Beauceron (an old French hunting dog).

The ‘butcher’s dog’ was the type of dog that accompanied Mr Stegmann on his journeys to Switzerland to buy in new stock. Butcher’s dogs were not a uniform type, as the term seemed to refer to the divergent types of the Metzgerhund, the ancestor in type to the Rottweiler, including a larger, more ponderous animal used for draft work and in particular for pulling the butchers’ meat carts, and a smaller, more agile type used mainly for herding. Although the butcher’s dog is credited as being one of the originators of the Rottweiler, in 1925 Max Kuensler wrote that ‘the sheep dog, the Weimaraner and the German Pinscher were involved, but certainly no Rottweilers or Terriers were known in Apolda at that time.’

The Thüringian Shepherd, which is now extinct as an individual breed, was known in the Apolda region before Herr Dobermann began breeding, and these were a cross between a type of Pinscher and a sheepdog. A German dog magazine article dated 1898 reads as follows:

At the end of the 1860s, the owner of a gravel pit at Apolda called Dietsch had a blue-grey bitch, a sort of Pinscher, which he mated with a black butcher’s dog. The sire already had the characteristic tan markings and was a cross between a sheepdog and a butcher’s dog. Herr Dobermann, a skinner who unfortunately died too early, crossed the issue of these two dogs, which became good guard dogs, with German Pinschers. That is the origin of today’s Dobermann.

Beaucerons dated back to the 1500s and were known to be in the region of Apolda at that time, having been left behind from the occupying forces of Napoleon’s army. The Dobermann shares many similarities with the Beauceron in the shape of its head, body and working characteristics. Beaucerons are known for their unique double hind dewclaws, and these occasionally surface in Dobermanns. (A litter born to the author in 2006 contained three puppies, each with double hind dew claws.)

German Pinscher (Arco v.d. Lauter, 12 April 1912).

Prinz Lux v Rhein, born 1904 (Graf Belling v. Gronland × Lucca v. Braunsfeld).

Beauceron, also known as Bas Rouge (Red Stocking). Int/Ir Ch Jupiler du Regard Mordant, owned by Steve and Jackie Barnes.

The town of Apolda is the capital of the Weimar region, and it is known that the Weimaraner hunting dog was in existence in the region from the 1600s. Certainly the shape, the close hair and the occasional (and highly undesirable) light eye in the Dobermann hold similarities. It is believed that the Weimaraner introduced the blue colouring to the breed, along with the blue Great Dane and the Beauceron.

The markings, colouring, shape and character of the various breeds have obviously drawn attention to their relationship with the Dobermann. The Thüringian Pinscher and Thüringian Shepherd both had a smooth black coat with red markings, and both were known to have an aggressive and sharp character.

Great Dane 1890 (working type).

The ancestor of the Rottweiler, the Metzgerhund, carried the same coat colour and markings as the Dobermann, although the coat was a lot thicker and wavier: this is still seen today, especially in dogs of Eastern European breeding. They were also the same height, but were solid in body, and had a much heavier head shape, with a shorter foreface-to-skull length: it is worth noting that head shape will readily revert to this proportion if breeders do not breed to keep the head as a blunt wedge instead of a triangular wedge.

The head shape of the French Beauceron resembles that of the Dobermann more closely than any other breed. Also in the varying colours all have the tan markings, with what were called Bas Rouge, or red stocking, which referred to the red rust leg markings. Beaucerons may also have a few white hairs on the chest, and although these are considered highly undesirable in Dobermann breed standards, they do still appear in Dobermanns worldwide.

The German Pinscher, the Beauceron and the greyhound all carry brown and tan, blue and tan, and fawn and tan in their genes. Phillip Gruenig and other references suggest that the English Black and Tan Terrier, which later became known as the Manchester Terrier, was used in the formation of the Dobermann, but breed authorities Otto Goeller and Herr Strebel both discount the use of them in the original formation of the breed because they were not known in the region of Thüringen until well after 1890, by which time the Dobermann was well established.

One cross breeding with a Black and Tan Terrier is recorded much later, in 1900, one cross breeding with the greyhound in 1906, and then some time later again with the Manchester Terrier. Karl Peter Umlauff, who was for many years President of the Dobermann Pinscher Club of Germany, bred Black and Tan Terriers for a short time in addition to his breed of choice, the Great Dane. His daughter Gerda was a noted breed authority in her own right.

Black and Tan Terrier, Zürich 1899.

The first dog show in Germany was held at Hamburg in 1863, but the first German Dog Stud Book was only established in 1876. In the 1882 issue it was noted that: ‘In the German dog shows there is some confusion about the English Black and Tan Terrier, also known as The Manchester Terrier, and our shorthaired Pinscher.’

In 1901, Richard Strebel (a German authority on canine matters) wrote: ‘It is doubtful if the Dobermann Pinscher is a true Pinscher; it should probably be classified more as a sheep dog.’ In 1933 the ongoing question as to the origins of the breed was once again raised by the German Dobermann Club, and the opinions of many old breeders were sought, including those of Goswin Tischler, who knew Herr Dobermann personally, and Robert Dobermann, Herr Dobermann’s youngest son.

The conclusion was that the German Pinscher was the main ancestor of the Dobermann. In 1947 Gruenig wrote that the Dobermann probably descended more from the Beauceron, as he did not believe it would have been possible to raise the shoulder height of the German Pinscher from 30cm to 70cm in only thirty years. Although Gruenig is an undoubted and unparalleled authority on the breed, this comment did come nearly seventy years after Herr Dobermann bred his first dogs, and a great deal may already have changed in this period.

The German Shepherd Dog (GSD) is also said to have a place in the history of the breed, but as a specific breed they themselves did not come into existence until 1899, well after Herr Dobermann’s dogs became established.

Discuss this as we may, just as our forefathers did, the exact origins of our breed will all remain subject to conjecture, and in reality it is as difficult to confirm them as it is to confirm those of a crossbreed.

In 1863, at the age of just twenty-nine, Herr Dobermann presented his ‘Dobermann Pinschers’ at the dog market in Apolda, where they were received most enthusiastically. With Herr Dobermann as their leader, the three men – Herr Dobermann, Herr Rabel and Herr Stegmann – soon became renowned for the quality of their fierce guard dogs, which fetched high prices and were sold as fast as they could be bred.

The Dobermann at this time was virtually unrecognizable from today’s dog in both character and looks. Ever alert, he was hair-trigger quick to react, with little or no bite restraint at the first hint of trouble, and over-keen to take on opponents, from other dogs to human aggressors. Responsive to the slightest provocation and with a high nerve threshold, this dog had become the ultimate deterrent to any attacker, and one that guarded his master without any thought for himself.

One of the most prominent bitches bred by Herr Dobermann was Bissart. She was originally named Bismarck, until a senior officer stated that it was unlawful to give a dog the same name as a great statesman (Count Otto von Bismarck lived in that time). Bissart was black with tan markings and a grey undercoat, and Herr Dobermann’s son Louis reported that his father bred some quality puppies from her. Most were black with red markings, although two were mainly black with red and white markings. Bissart had a daughter named Pinko, who was a natural bobtail, and he subsequently bred her to a bobtailed stud, but there was only one bobtailed puppy in the litter. There were also blue puppies in that litter, which gives credence to the early influence of the other breeds mentioned that were known to carry this colour.

ESTABLISHING A BREED STANDARD

After Herr Dobermann’s death in 1884 it was recognized that the development of the breed up until that time had been conducted in a very haphazard manner. Popular though it was, dog breeding was not highly regarded as a profession, and although there were by now several fanciers of the breed, the lack of any formal registration system impeded progress. Dogs that were bred or kept in their owners’ name, usually changed names with subsequent ownership, so tracing the parentage of these dogs was often very difficult.

Herr Oskar Vorwerk of Hamburg encouraged several hobby breeders to join forces and establish a breed standard that could be recognized by the German National Kennel Club. Existing Dobermann owner and breeder Otto Göller and his wife were persuaded by Vorwerk to take up the task of developing what was still a very undeveloped and rough breed. Göller eventually became known as the architect of the breed, and he further substantiates the origins of the Dobermann when he wrote:

I am quite convinced that it was principally the German Shepherd dog, the smooth-haired Pointer, the blue Great Dane, and the German smooth-haired Pinscher which played a remarkable part in the creation of this breed. Those dogs that I bought in the villages had no undercoat, or very little, red markings, short, absolutely black hair like hounds, little marked lips, and long toes. Those dogs which came from Apolda were more like German Shepherd dogs and Pinschers.

When the number of dogs overwhelmed their accommodation, they were often placed in suitable ‘breeding homes’, and this remains common practice in Germany and other countries.

Even by this stage the Dobermann was physically not particularly advanced in type, and a contemporary show report in that year describes them as being ‘coarse and heavy-headed, inclined to be long and wavy-coated with thick grey undercoat and straw-yellow markings’. White spots on the chest were commonplace, and they generally appeared to look like a small Rottweiler.

Göller was already familiar with the exceptional intelligence of the Dobermann, but he also recognized that the dogs were too fierce and vicious, and although he wanted to retain its superb guard-dog characteristics, he knew that if these dogs were to be accepted into general ownership a more amenable temperament was required (though what we term as generally amenable, and what was the case at the turn of the century, were very different indeed!)

Otto Göller’s breeding name was ‘von Thüringen’. On 16 May 1896 he bred a litter by the sire Lord v. Thueringen (alias v. Dennstedt/v. Gröenland) out of the bitch Schnuppine v. Dennstedt; the male pups were Lux, Schnupp, Landgraf and Rambo, and the females Tilly1 NZ17, Helmtrude, Hertha and Elly. These dogs are among those that formed what is termed the ‘germ cell’ of the breed, as so many important lines descended from them.

Hertha v. Gröenland.

A founding breeder who bred closely with Herr Göller was Goswin Tischler, whose kennel was named ‘von Gröenland’. In 1898 his black female Tilly 1 NZ17, bred by Otto Göller, was bred to Lux v. Gröenland (Nero × Ceres), and the resulting progeny were of such high quality that they were known as the ‘five-star litter’. They included Greif DZ184, Tilly ll NZ28, Krone DZ2, Lottchen DZ8, and Graf Belling NZ1 (the last two were later known as Lottchen v. Thueringen and Graf Belling v. Thueringen, after they were bought by Otto Göller). It is impossible to choose just one particular dog from this litter as a breed example, as they were all fundamental to the creation of the breed, but what is of greater importance is how those early dogs were bred together to provide its foundations.

Graf Belling and Gerhilde v. Gröenland/v. Thüringen. Graf Belling v. Gröenland was the first Dobermann registered with the National Dobermannpinscher stud book, number NZDB1, in 1898.

We know that many of the dogs were mated very closely together to create a Dobermann type, as it is otherwise impossible to create a breed that produces itself to type in such a relatively short time from completely unrelated dogs. During these early years of breed development in the late 1800s, this very tight line-breeding would have consisted of matings between half and full siblings, and grandparents to grandchildren, to cement breed type and powers of heredity; thus the combination of the apparent quality and hereditary powers of Göller’s 1896 litter and Tischler’s five-star litter resulted in dogs such as Hellegraf, who carried great hereditary powers. Although some of the bloodlines of these dogs have died out, many others of these early litters are still found throughout the world, and the progress of the breed would undoubtedly have been considerably slower without these incestuous breeding combinations.

REGISTRATION

In 1899 Otto Göller and his colleagues founded the National Dobermannpinscher Club, and the breed standard for the Dobermann became adopted by the German Kennel Club in 1900, requiring every breeding animal to be registered.

The German Kennel Club (DPZ) had for some years formalized pedigree dog breeding, and dogs were usually registered in one of the stud books that accorded to the locality in which they were born and the clubs of that area. The stud book prefix of NZ refers to the National Dobermannpinscher Stud Book. DZ was the stud book published by the Dobermannpinscher Club of Hamburg, the Dobermannpinscher Verien, and the Dobermannpinscher Verband, and the prefix ‘DPZ’ refers to the German Kennel Club.

Initially the colour of the Dobermann was listed solely as black and tan, but in 1901 the standard for colour was changed to include brown and tan, and blue and tan, and remains as this today.

The first Dobermann registered (retrospectively) with the German Kennel Club was Louis Dobermann’s female Schuppine, who was registered as DPZ1 as a tribute to him. Graf Belling v. Gröenland (alias v. Thueringen) was the first Dobermann registered with the National Dobermannpinscher stud book, number NZDB1, in 1898.

The male Bosco born in 1893 and female Cäsi in 1894 were the oldest Dobermanns to be entered in the new Dobermann stud books. Although they were not initially registered themselves, they became registered when their most famous son Prinz Matzi von Gröenland was born and registered in 15 August 1895 DZ7. Prinz Matzi von Gröenland was shown in Berlin where he became the first Dobermann Sieger. He was purchased by Otto Göller, and later given to Otto Vorwerk in Hamburg.

Matzi was not a perfect Dobermann even for those days: he was of a coarse type with long hair and thick undercoat, his eyes were too light and his skull was very heavy. He also had a very tough and sharp temperament, which he passed to his progeny. A story is told of the day of his arrival in Hamburg, where he attacked and apparently killed a Great Dane that Herr Vorwerk had just purchased for the great sum of DM 1100. Matzi was promptly returned to Otto Göller in Apolda with the message ‘before I shoot him I want you to use him for breeding’. Otto Göller did indeed use him for breeding, but it seems he never was shot because after a few years he was sold as a stud to Frankfurt. He sired some good local dogs, such as Siegwart v. Hochheim, but after a few years there was no record of his progeny, and he was of no real importance in the founding of the breed.

Of particular value to the breed were the v. Ilm-Athen dogs of Herr G. Krumpholz from Wikkerstedt near Apolda. In 1899 his kennel marked the beginning of a very important turning point in the development of the breed, with a Dobermann female named Lady v. Ilm-Athen. Her parents were reputedly Bosko vom Hensdorf (himself sired by Bosco) and Ada v. Apolda, who were both unregistered, but Lady v. Ilm-Athen carried the blood of the Manchester Terrier, and her value to the breed in the whelping box was significant, providing a clean outline and dark markings.

When she was mated to Greif v. Gröenland (Lux × Tilly) they produced Prinz v. Ilm-Athen in 1901, who became a highly influential stud dog, benefitting the breed with new genetic input especially in terms of depth of colour and refinement of style. His progeny had a greatly improved shape, and bore what became the distinct and dark markings such as the thumbprint on the cheeks and feet. These traits were passed on through many of his descendants and are synonymous with the breed as we know it today. Prinz v. Ilm-Athen is behind the many great breeding and show dogs of the early twentieth century.

The previous two decades had brought particular kennel names to the fore, and in addition to the v. Thueringen and Ilm-Athen importance, Aprath, Isenburg, Burgwall and Luetzellinden were also significant.

(Landgraf) Sighart v. Thueringen, 14 November 1900, was of significant value to the emerging Dobermann breed and produced a very dominant male line: five distinct main bloodlines emanated from him. One of the most important Dobermanns of this time was his son ‘Hellegraf von Thüringen’ DZ172, born in 1904 out of Ulrichs Glocke v. Thueringen, whose dam Freya v. Thueringen NZ3 (bred by Herr Seifert of Weimar under the Thueringen name) was one of the great brood bitches. The famous Dobermann historian Philipp Gruenig later wrote of Hellegraf that ‘he was a paragon of beauty, perfection and power. His was a degree of genuine “Adel” that will be difficult to surpass or even equal. Let the name be written in letters of fire’.

Hellegraf was brown, but from his sire Sighart’s line he carried all four colours, so clearly the genes for all colours were already established by this time. Landgraf Sighart was known to be the carrier of colours, as his sons Hans and Hellegraf were both brown, and his grandson Gunzelin (Prinz v. Ilm-Athen × Suse v. Thueringen) was blue. Hellegraf was reportedly hard to fault in himself, but even more notable was his power to transmit breed quality. Ten main lines radiate from him, and many more minor lines.

A bitch which is often under-reported for her significance to the breed is Lady v. Calenberg: although unregistered (she was part – probably half – Manchester Terrier), she and her progeny became renowned for throwing close, smooth and short coats with great depth of colour. She is best known as the grand-dam (through her son Tell v. Kirchweyhe × Thina v. Aprath) of two important brown brothers, Fedor v. Aprath and Hans v. Aprath (later v. Walde). Both these males became known for contributing a great depth of dark brown coat colour with strong rust markings on their progeny, and had long, elegant and balanced heads influenced in part by the Manchester blood. Neither were big males, but both were said to have had particularly good front angulation and sound conformation. Hans was sold to Switzerland, where he played a large part in establishing the breed there. The line was also noted for their high predatory inclination.

Fedor v. Aprath b.1906.

The Greyhound was introduced to the breed for speed and elegance, and although many breeders used Greyhounds or Greyhound blood in their breeding, it did not bring such positive benefits as the Manchester Terrier blood had done. Not everyone was pleased with these crosses, with many specialists warning that the working abilities of the Dobermann would be diluted by the prey drive of the Greyhound, and that physically the dogs were too slender and lacking in substance, with a narrow pigeon chest and arched back. The head type was also markedly different.

At a general meeting of the National Dobermannpinscher Club in Apolda in 1905, it is reported that Otto Göller warned against these crosses, and instructed judges of Dobermanns to withhold first prizes at shows from terrier-type dogs, those with heavy, coarse Dane and Rottweiler-type heads, and ‘brindled’ dogs. Herr Gruenig also later warned against further Manchester Terrier cross breeding, as the shoulder position caused restricted (terrier-like) movement, which impeded the ‘free flowing movement of the Dobermann, who must be able to gallop and move freely without being hampered by such construction’.

In 1906 a blue male, Gunzelin v. Altenburg, was born (Prinz v. Ilm-Athen), as was another in 1908 from almost pure v. Ilm-Athen lines, named Loni v.d. Wendendburg. The depth of colour in the markings was something that breeders were endeavouring to achieve on all colours at that time; in particular tan markings were more a faded yellow than the desired dark rust tan that had been introduced by Manchester Terrier breeding.

Nevertheless a recognizable and consistent physical type had begun to emerge, and a few individuals stood out as particularly good examples of the breed. Sturmfried v. Ilm-Athen, born in 1906 (Prinz v. Ilm-Athen × Betti 1 v. Ilm-Athen), was said to lean heavily to his grandsire, Greif v. Gröenland, on both sides of his pedigree, and he was renowned for throwing both great attitude and particularly deep colour in the black and red markings, notably from his grandmother’s (Lady v. Ilm-Athen) Manchester Terrier blood. Sturmfield’s many successful descendants, in particular his grandson Prinz Modern v. Ilm-Athen, have assured him of a place in the history books.

Greif v. Gröenland.

Lord v. Ried, born 1907, was from the sire Hellegraf to Nora v. Ried, whose pedigree carried dogs of very strong hereditary powers on both sides. Lord v. Ried inherited his imposing stature and ‘Adel’ from Hellegraf and his dam Nora, whose pedigree, as mentioned above, returns to dogs of great hereditary value, such as Graf Wedigo v. Gröenland. In this year Gruenig noted that the Dobermann had ‘achieved an advanced degree of evolutionary development’, and remarked how he well recalled the sensation created at the time when this novice was first exhibited at Frankfurt, where he won the Sieger title. Gruenig also observed that ‘mere astonishment was heightened to dumb wonder when Helmuth v. Aprath and Annemarie v. Thueringen also appeared’.

Lord was a well used sire, with many of the show dogs of the 1930s being sired by him and his progeny, along with other dogs of high quality. Their influence was therefore now being spread over a wide geographical area, resulting in a rapid expansion of the gene pool of a renowned and recognizable type.

In 1908 a bitch called Stella was born from Max v. Kaisering/v. Isenburg × Flora v. Reid. There were various breeding experiments in the region at that time, and it was believed that her breeding included a black (English) Greyhound. Her daughter Sybille v. Langen was apparently ‘visibly like a Greyhound’. Other references for the period demonstrate a clear line pedigree back to v. Reid, v. Ilm-Athen, and v. Thueringen breeding. Whichever was the case, Sybille became the foundation bitch of the Silbergberg kennels; the Blankenburg line also had a marked influence on the breed.

This was a great era for the breed, with an enthusiastic following of Dobermann fanciers, thriving clubs, many dog exhibitions, and breeders uniting to improve the breed. The reputation of the Dobermann was beginning to reach far beyond Germany.

It was also in 1908 that Dobermanns first arrived in America. Bertel v. Hohenstein and Hertha v. Hohenstein were imported by a Mr Jaeger, who with a partner named Mr W. Doberman (perhaps related to the original Herr L. F. Dobermann) established their kennel which they called ‘Doberman’. Of course no one would be permitted to register a kennel name with the name of a breed these days, but perhaps this is where the spelling with a single ‘n’ originated. Hertha became Hertha Doberman, and the following year a dog they bred called Doberman Dix became the first US Champion Dobermann.

From the earlier experimental matings that had been so denounced by pillars of the breed, a dog was born in Germany in 1909 that was to take the breed forward in a new direction. The dog was Prinz Modern Ilm-Athen, by Lux Edelblut v. Ilm-Athen out of Lotte v. Ilm-Athen, the bloodline returning through Edelblut to Hellegraf. Lotte was the daughter of the very prominent Sturmfried v. Ilm-Athen, who was a refined black dog of quality type, and transmitted the strong, clear markings from his paternal grand-dam Lady v. Ilm-Athen with her Manchester Terrier blood.

Prinz Modern v. Ilm-Athen.

The pedigree of Prinz Modern v. Ilm-Athen shows the practice of repeated incestuous breeding to stamp type. Very close incestuous matings were not uncommon in the formative years of the breed to create type. It is also noteworthy that almost a hundred years later, on 1 September 1997, full siblings Astor and Arielle d’Amour del Citone produced the world famous Gino Gomez del Citone.

Apart from his smaller stature, Prinz Modern v. Ilm-Athen had the breed type and shape of the Dobermann as we know it today, although his head was apparently too wide and heavy. Furthermore reliable references report that his character was cowardly, and according to Gruenig ‘much damage was done to the breed by the spread of this character’. Nonetheless he was a very important sire.

Aside from the total lack of record keeping it is impossible to put together a factually correct pedigree from these formative years of breed history, so pedigrees from this era may contain inaccuracies. Names were frequently changed on ownership transfer, different birthdates were listed for the same dogs, and all the variations of Schnuppe were widely used, just as Max, Zeus and Apollo are these days. From 1912 to 1928 there are at least six Dobermanns listed with the name Lux, six Trolls, five Lords and six Lottes, not even counting the Prinzes. The subject of original pedigrees and significant dogs in this period of history requires so much investigatory detail that it merits a book to itself. (See Recommended Reading.)

THE WAR YEARS 1914–1918

Dogs have been used in war from ancient times, giving great advantage to their accompanying forces. The Germans had been developing formal training for dogs from the late 1800s onwards by encouraging people to attend village training schools, with regular competitions between clubs. Therefore by the time World War I broke out the Germans had literally thousands of dogs trained for a variety of roles, including for defence or attack, to act as sentries, and to search for prisoners – these alone saved more than 4,000 Germans who would otherwise have died or been taken prisoner. The British and Allied Forces had no formal dog-training programme for service work until at least 1910, so were way behind the Germans in the advantages of using dogs for war work.

However, not all dogs were trained in war work or ready for action, and for those that were not, times were very hard for any dog, let alone for pedigree dog breeding. As Phillip Gruenig observed:

Most of the German breeders were at the front, and inescapable necessity compelled their remaining dependants to have their highly prized and dearly loved household pets put to a merciful death as the only alternative to starvation and suffering along with their owners. How deeply this cut into the heart of a true dog lover can be testified by me. On the second day of mobilization, the day on which I was ordered to the front, no less than eighteen half grown pups from my kennel fell victims to strychnine. It had to be, to safeguard them from the more horrible fate of death from slow starvation. In a moment of weakness induced by the hope of saving them, I retained two of my best dogs, Walhall v. Jaegerhof (a litter sister of Edelblut) and Ebbo v. Adalheim (a son of Marko v. Luetzellinden). They died miserably of malnutrition in 1916. Untold thousands suffered the same pain I did, for wives and children barely escaped the same fate of starvation. How wonderfully far has our much-touted civilization brought us!

Phillip Gruenig

Dobermanns were used to advantage by the Germans in the war, particularly as messenger dogs, and dogs were both chosen from private owners and bred by the military. It therefore seems odd that so many potentially good dogs were destroyed when they could have made great use of such dogs for service. Despite having been shot through the bone, one extraordinarily good Dobermann male named Schreck von Peronne continued to deliver a message, finishing his task on three legs. Dogs were also used to carry cables, and another Dobermann called Hans carried a telephone line for more than half a mile in two minutes whilst under artillery and gunshot fire. Hans was apparently shown to Hitler on a formal visit as an example of the excellent German breed.

THE WAR YEARS

Many breeders managed to save their dogs’ lives by sending them to neutral countries, and the loss of so many good dogs from Germany was often the gain of other countries.

Private breeding did still continue in some regions of Europe less affected by the battlefronts, and the stud dog Edelblut v. Jägerhof, 25 January 1913 (Prinz Modern v. Ilm-Athen × Tatjana v. Jägerhof) was advantageously placed in the relatively safe area of the Rhineland near to Holland, to be used widely at stud. By the time he died he had been bred to 104 females, and his name can be found on most important Dobermanns in the world today.

This preponderance of Edeblut’s bloodline prompted Gruenig to make dire warnings about the dominance of one dog on the breed, par-ticularly with respect to transmitting not only their positive attributes, but also their negatives. Edelblut had few faults, but is reported to have had ‘loose shoulders’, which he passed on to all his progeny until, according to Gruenig, ‘all of Western Germany has succumbed to its evil’.

World War I military Dobermanns.

Exactly the same problem was perpetuated with the over-use of Lux vd. Blankenburg. It was warned that by relying too largely on a leader dog at any time or in too tight a region, the leader’s faults would be established to too great an extent to rid the breed of faults. Gruenig’s warnings against oversaturation by any one blood, with its attendant faults, still hold true today.

The arrival of Dobermanns in other countries due to the war prompted a surge of interest by overseas breed fanciers, and German breeders began to rapidly re-establish the breed. In 1916 the brown male Salto v. Rottal settled in Czechoslovakia, where he helped found the breed; in 1919 the Austrian Dobermanpinscher Club was formed; and in Holland, Edelblut’s brown progeny Urian and Undine v. Grammont were important for the breed.

Burschel v. Simmenan, b.1915 (Arno v. Glucksburg, down from Sturmfried, Prinz v. Ilm-athen, Stella and Lotte, x Gudrun v. Hornegg, down from Lord v. Ried, Hellegraf, and Betty) had survived the war and later became a Sieger winner. Burschel played a major role in re-establishing the breed in post-war Germany, and his son Lux vd. Blankenburg was one of the top sires ever in Germany.

Burschel v. Simmenau, 1915.

In 1921 the Dutch-bred brown male Favorit vd. Koningstad (Carlo vd. Koningstad × Angola v. Grammont) was born, and he had great success throughout Europe at shows and stud. Favorit was sold for a large sum to America. He was said to be the best sire to be seen yet in America, where he greatly increased the popularity of the breed.

Prinz Favorit vd. Koningstad, about whom Gruenig wrote ‘a well built Dobermann with a perfect head, the desired goal for permanent head type’.

The twenties and thirties were boom times for the Dobermann, and the enthusiasm for pedigree dog breeding reflected the positive post-war mood of the era. Membership of the Dobermann clubs in Germany was around 3,000 members, and the breed thrived.

Post War

Just four years after the end of the war, in 1921, 119 high quality Dobermanns were shown at the Munich Sieger Show. The following year at the Sieger show in Berlin the quality was even better, with 233 Dobermans entered.

In that same year of 1921, the Doberman Pinscher Club of America (DPCA) was formed, and just two years later, in 1923, three German breed specialists were invited to judge in America.

Sgr Muck v. Brunia.

Three generations of Sieger and BIS-winning dogs started with Sgr, Int. Ch. Muck v. Brunia b. 1929 (Luz v. Roedeltal × Hella vd. Winterberurg), who became a Sieger and was used to advantage in Europe before being sold in 1933.

Before he left Germany, Muck sired double World Sieger Troll vd. Engelsburg b.1933 × Adda v. Heek), whose bloodline lies behind many Russian dogs. Troll is also behind the founding dogs to the UK. One of Troll’s best known sons was the male Ch. Ferry von Rauhfelsen (of Giralda). Ferry’s dam was Ch. Jessy v. Sonnenhoehe b.1934, also from Germany, and was said by the DPCA to be the most important dam of her time.

Ferry von Rauhfelsen.

Ferry von Rauhfelsen with owner Geraldine Rockerfeller-Dodge (Giraldo).

Jessy v. Sonnenhoehe.

THE WAR YEARS 1939–1945

In World War II times were again hard for both the individual and the breed. However, having already established military breeding and training centres in World War I, the Germans were well prepared for the use of dogs in service again. Dobermanns and other breeds were used for guarding prisoners in concentration camps, tracking escapees and helping to find wounded soldiers.

Chief of Staff of The German Army Dog Office was Dr Bruckner, who knew a great many dogs of all breeds. Dr Bruckner stated that:

The Dobermann usually follows a trail with his nose rather high, but is as sure a trailer as the breeds which work close to the ground. As a result a Dobermann can follow the scent, especially when artificially laid, very fast. When in training the breed is inclined to be a trifle more headstrong than some other breeds, particularly the easily handled German Shepherd, however, he enjoys working and learns quickly, and in spite of a fondness for running, he is serious about his work and will always give satisfactory results when properly bred for working qualities.

Dobermanns in Service for the Americans

Before 1942 the Americans did not have a formal training programme for dogs in the military. However, although they did not become involved in the war in Europe until much later, they did need to regain and protect the Pacific islands, which had been occupied by Japanese forces. Having seen the successful use of Dobermanns and German Shepherds by the Germans in World War I, it was felt that a dog unit was necessary, and in 1942 the Marine Corps War Dog Training Facility was established at Camp LeJeune, North Carolina.

Dobermann in training to release his master in World War II.

The Dobermann Pinscher Club of America (DPCA) was approached to procure Dobes for the newly formed unit, and DPCA officials gave their own time and money to help find and assess suitable dogs for them. Many Dobermanns were offered by private owners and members of the DPCA, and an initial fourteen were chosen to go the Marine Corps under the direction of Captain Samuel T. Brick. The First Marine Dog Platoon and their Dobermanns landed on Bougainville, Solomon Islands on 1 November 1943.

First Marine Dog Platoon landing at Bougainville, South Pacific 1943.

The dogs were used in advance positions as sentries, and for searching out enemy combatants in caves and dugouts. Their incredible senses enabled them to detect the threat of danger, and on one occasion they detected the presence of Japanese troops half a mile away.

The Marine Dogs earned the nickname of ‘Devil Dogs’, and the people who lived through the Japanese occupation remember them with great awe and respect for their invaluable part in the liberation of the islands. The dogs were revered by their handlers who naturally became very close to them, and any injured dogs were carried on stretchers to be treated by camp doctors as carefully as any human soldier.

Soldier and his injured Dobermann with a captured Japanese flag at Okinawa.

The Marine Corps and their Devil Dogs were officially credited with leading 350 patrols during the battles, accounting for over 300 enemy killed or captured.

A DEEP BOND

Soldiers wrote home to their own families, and those of the dogs, and Dogs For Defence HQ in New York received a constant stream of letters home from the dogs to be forwarded to their owners. One such letter was from a Marine who wrote to the owners of his Doberman: ‘During the past months, Judy and I have been through a lot together and I have become very fond of her. I would like to have her after the war. So if you can possibly see your way clear to part with her I would be forever grateful to you and although I am not a person of any wealth, I would be only too happy to pay any amount I could afford, if I could have her.’ Owners understood the deep bond that their dogs now had with their handlers, and invariably agreed to the requests.

FANGO THE GUIDE DOG

One story from the end of the war was of a German soldier who was blinded. He was allocated a Dobermann called Fango as a guide dog who after just three months training, took his owner out and back home on the underground each day. The soldier wrote: ‘I could have no better comrade. He gave me back my self assurance and I feel now that my fate will be bearable only with my Dobermann as a companion.’

The ‘Always Faithful’ memorial statue in Guam was commissioned by the United Dobermann Club and sculpted by Susan Bahary. It is a permanent remembrance of the courageous Dobermanns that gave their lives in service to America and the US Marine Corps during World War II.

THE POST-WAR YEARS

In October 1950 the German Dobermann Club were allowed to hold the first working dog trial since the war, and Dobermann breeding once again resumed.

The acquisition of so many of Europe’s top Dobermanns by the Americans was the saving grace of the breed, as the six years of war took its toll on the breed in the homeland, where many Dobermanns and their breeders died. Most remaining breeders had lost their homes and had few, if any Dobermanns to start breeding again.

Meanwhile the Dobermann in America had been thriving, with some serious and dedicated sponsors including Mr Fleitmann (Westphalia), Mr Glenn Staines (Pontchartrain), and Mr Moore (White Gate). These gentlemen collectively imported many great dogs, and with George Earle III, were among the founding members of the DPCA. They gradually diverged in their view of the ideal Dobermann, and although they remained lifelong supporters and friends, their dogs became markedly different in style.

Pathfinder Dobermanns

In 1936 Glenn Staines had begun training Dobermanns as guide dogs for the blind under the name of ‘Pathfinder’. He did not use the top winning dogs ‘for fear of introducing undesirable character to his breeding’. He donated many dogs to blind people who simply couldn’t afford to pay, and in 1945 donated dogs to blinded veterans. By 1951 over 1,000 Pathfinder Dobermanns had been placed with blind owners, and they were in demand right up to his death in 1951.

Four ‘Leader’ Dobermanns. Note the height of the breed.

Joanna Walker of the world-famous Marks-Tey Dobermanns was one of the pioneers who promoted the popularity of Dobermanns in the early years. She was a passionate supporter of the ‘seeing eye’ Pilot Dobermann programme, which started in Ohio in the 1950s. That Dobermanns are used for so many service dogs in the USA is largely credited to the pioneering efforts of people such as Joanna Walker and Glenn Staines. It is a great shame that service dog organizations in the UK have a policy not to use guarding breeds.

Am. Ch. Marks-Tey Shawn CD and Joanna Walker. This dog’s pedigree returned to Dictator v. Glenhugel and the old Damasyn lines famed for their heads, the quality of which is evident in this image.

Names of Influence

The 1940s were a golden era for the breed, with many great dogs. Peggy Adamson, who is considered to be one of the early architects of the Doberman in the USA and would become a fundamental part of US history, wrote of what she called ‘Illena and the Seven Sires’. These seven dogs and one bitch each produced over ten champions. Their names were Ch. Dow’s Illena of Marienland, Ch. Favoriet v. Franzhof, Ch. Westphalia’s Uranus, Ch. Emperor of Marienland, Ch. Domossi of Marienland, Ch. Alcor v. Millsdod, and Ch. Dictator v. Glenhugel.

These dogs and the inter-marriages of their progeny collectively formed the backbone of a great and lasting legacy for the American Dobermann.

Damasyn: Peggy Adamson became world famous for her Damasyn kennels, established in 1945. Ch. Dictator v. Glenhugel b.1941 was bred by John Cholley and owned by Peggy, and where Ferry could not be touched, Dictator had a hugely beneficial effect on the perception of the breed by extending a gentle paw to greet children and being as elegant and dignified as his owner. He won a Group 1 at Westminster, and sired over fifty-two champion progeny and many more grandchildren champions.

Ch. Dictator v. Glenhugel.

All the Damasyn dogs were trained to a minimum of CD standard. Peggy’s dogs were always expected to have excellent breed type and temperament, and the Damasyn head and character are still imprinted on the breed.

Ch. Rancho Dobe’s Storm: In 1949 another all-time great dog, Ch. Rancho Dobe’s Storm, was born from Ch. Rancho Dobe’s Primo × Ch. Maedel v. Randahof ×. Bred by Mr and Mrs Brint Edwards, Dobe’s Storm was a sensation in the ring and became the first Dobermann to win BIS at Westminster in both 1952 and 1953. He is one of only eight dogs to win BIS at Westminster more than once, and the only Doberman to have done so. Notably, his grandsire Ferry v. Rauhfelsen was the first Dobermann to win BIS at Westminster. Royal Doulton modelled their Dobermann figurine on him, and Rancho Dobe’s Storm is so famous he even has his own Wikipedia page.

2THE DOBERMANN IN GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND

Despite the breed being well established in the USA, only a handful of dogs were imported to the UK before World War II. One of the first Dobermanns in the UK was seen at Crufts Dog Show in 1928 at Crystal Palace, where it was then held. The dog was owned by a famous cookery writer, Mrs Elizabeth Mann, and for most, it was the first time a Dobermann had been seen. Her name was Ossi v. Stresow b.1925 (Cuno v. Stoizenberg × Flora v. Stresow), and she was flown in from Berlin in 1928 in whelp by (yet another) Harras v. Wendelstein, who was downline from Prinz v. Ilm-Athen. Ossi’s litter produced six puppies born in late 1928, and records show that only one was subsequently bred from: a dog called Otto, who was later mated to an imported bitch Wally vd Margaretenau b.1928, whose great grandsire was Troll v. Blankenburg.

Names of Influence in the 1940s

Birling: George Lionel Hamilton-Renwick was born in 1917 at Birling Manor, Northumberland, and had a founding impact on the development of the Dobermann in the UK. He appeared in the Crufts Best in Show ring on no fewer than eleven occasions with three different breeds. He also judged many times at Crufts and abroad. Hamilton-Renwick was the first person to import Pharaoh Hounds to the UK but he was most famed for his Dobermanns, which were his real passion.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!