16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

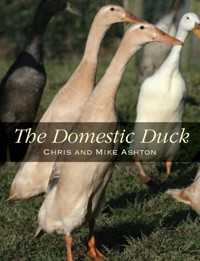

Most domesticated ducks are descended from the wild mallard and over the centuries many different breeds have been created. They have been kept as pets, or for their ornamental value, or have been farmed for their meat, eggs and down. In The Domestic Duck, Chris and Mike Ashton explain how these breeds have been developed and how to look after them. Contents include: Breeds, their origins and characteristics; Classic ducks from all over the world; 'Designer' ducks of the twentieth century; Management of adult stock; Breeding and rearing ducklings; Common problems and ailments. Fully illustrated with over 170 black & white photographs and 35 colour photographs depicting examples of the pure breeds and all aspects of their management, this is the essential manual for all duck-keepers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 540

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

The Domestic Duck

CHRIS AND MIKE ASHTON

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2001 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

Paperback edition 2008

© Chris Ashton 2001 and 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 970 4

All ducks and photographs are the authors’, unless otherwise credited. Diagrams by the authors and David Fisher, unless otherwise credited.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part 1

Breeds of Ducks: History and Characteristics

Chapter 1

Classic Ducks: The Old Established Breeds

Chapter 2

The Designer Ducks

Colour plate section

Part 2

Adult Ducks: Behaviour and Management

Chapter 3

The Origin, Physiology and Behaviour of the Mallard

Chapter 4

Purchasing Stock

Chapter 5

Managing Adult Stock

Part 3

Breeding Ducks

Chapter 6

Selecting and Managing Breeders

Chapter 7

Eggs and Incubation

Chapter 8

Rearing Ducklings

Appendix:

Keeping Ducks Healthy – Preventative Care

Useful Addresses

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Many people have contributed to the shared knowledge of the breeds recorded in this book. Some of this material has not been previously written down and much of the written source material from the nineteenth and early-twentieth century is now difficult to find. We therefore felt it useful to record what is known about domestic waterfowl breeds in Britain at this time.

Special thanks are due to John Hall whose extensive knowledge and life-long involvement with waterfowl has proven especially valuable in the sections on Call, Crested, Cayuga and Hook Bill Ducks.

Tom Bartlett, Vernon Jackson, Stephanie Mansell, Gilbert May, Anne Terrell, Fran Harrison and many other British Waterfowl Association members have also played a part in giving their views on particular breeds.

On the continent, Kenneth Broekman and Hans Ringnalda have given advice on the Dutch breeds, and Evelyne van Vliet, Marie Buttery and Holgar Heyken have translated material from Dutch and German.

On the technical side, F. M. Lancaster was kind enough to check over, and give advice on, the introduction to plumage colour genetics in the ‘Designer Ducks’ section. Victoria Roberts has given up her time to proof-read and her help is much appreciated.

Thanks are also due to Poultry World and Sacrewell Poultry Trust for access to old copies of Poultry World; also The Feathered World for access to magazines from the early twentieth century.

Introduction

For thousands of years ducks have been a source of interest for human beings, mainly for very practical reasons – food and warmth. Duck down from many species, including the famous Eider, has continued to provide very efficient insulation for clothes and bedding. Duck eggs are a good source of protein and in many cultures duck meat has long been a favourite food. Traditionally these were obtained by rifling nests or capturing the birds themselves. For nomadic peoples, raiding nests and trapping or shooting the ducks would have been common activities in many parts of the world. Only when settled communities evolved, around the development of cereal agriculture, were more permanent means of keeping ducks made possible.

Although most ducks are good fliers, it is very easy to ‘clip their wings’ and impose simple captivity and, because many species nest on the ground, obtaining hatching eggs would be fairly straightforward. What is amazing is that out of 147 living species of ducks, geese and swans, only four of them have provided the bulk of domestic waterfowl throughout the world. Two of these are geese: the Greylag (Anser anser) and the Swan Goose (Anser cygnoides). Two of them are ducks: the Muscovy (Cairina moschata) and the Northern Mallard (Anas p. platyrhynchos). It is the latter that appears to be the ancestor of all but one of the breeds of domestic duck. The Common Mallard is the same species as the big Rouen and Aylesbury as well as the little Black East Indian and the tiny Call Duck. This is all too evident if a Wild Mallard drake flies into the breeding pens and manages to fertilize whatever domestic ducks are on the premises. These birds are highly sexed and highly successful. This is one of the prime reasons for choosing the Mallard in the first place.

Fig 1 The Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata), a perching duck from South America, now common around the world as a farmyard duck. This is a different species from the Mallard, which produced all of our other domestic ducks.

‘Mallards rank among the most successful of all avian species, and throughout their wide distribution (which encompasses most of the Northern Hemisphere) they occupy a tremendous variety of habitats, ’ writes Frank S. Todd in his Waterfowl: Ducks, Geese and Swans of the World (1979). He goes as far as to assert that the Mallard may well have been the first domesticated bird, pre-dating even the chicken. There are records of the Romans establishing a duckery in the first century using Teal or Mallard eggs. The Egyptians certainly kept Mallard several centuries before the birth of Christ and the Chinese were probably keeping them much earlier. One tell-tale piece of evidence lies in the curled tail feathers of the Mallard, a feature found in all but one of the domestic breeds. Charles Darwin asserts: ‘In the great duck family one species alone – the male of Anas boschas [now Anas p. platyrhynchos] – has its four middle tail feathers curled upwardly’.

Another characteristic shared by domestic and wild surface-feeding ducks is the speculum, a patch of iridescence on the secondary flight feathers. It is common to both male and female ducks and tends to be accompanied by black and white bars on the secondaries and greater coverts. This feature is retained in many of the domestic breeds, although it is obscured in some cases by masking genes and various dilutions.

Ancestors

Whether all of the breeds, other than the Muscovy, are derived from the single species of Northern Mallard is a matter for speculation. Certainly, in the wild there are close relative species that will interbreed with the Mallard, just as the two geese species mentioned above will hybridize to produce viable breeds like the Steinbacher and some of the Russian geese. One of the closest to the Mallard is a subspecies, Anas p. conboschas, known as the Greenland Mallard. It is larger and lighter-coloured than its common relative, partly marine in its habitat and requires two years to reach sexual maturity. It looks very similar to the Trout Indian Runner, apart from the upright stance and the Runner’s single year to maturity. Another close full species is the American Black Duck, Anas rubripes, which will certainly hybridize with the Mallard, according to Todd (1979). This is a contender for the ancestor of the Cayuga and the Black East Indian Ducks, both of which were developed within the breeding range of Anas rubripes.

The question remains, however: if so many domestic breeds have emerged from such a small family of wild ducks, most of which are very similar to each other, why are the domestics so different? Why are there massive ones and minute ones, black ones, brown ones, white ones, pied ones and Mallard-looking ones? The answer is likely to be ‘natural variation’ or mutation. Within any species there is a range of genetic material. It is even possible to get the odd white blackbird, but within the constraints and competition for survival of the natural habitat only the most conservative and viable will survive. It is theoretically possible for wild Mallards to generate large white Aylesbury lookalikes, yet what would their chances of survival be in the wild compared to their lightweight, camouflaged, high-flying siblings? Natural selection favours the most efficient adapters to the specific environment. Take away the constraints of the wild; protect the birds from predators and bad weather; give them buckets full of high-protein food and the Aylesbury will survive as well as its wild brothers or sisters – at least until cooking time.

Fig 2 The common tame duck (the Mallard), ancestor of all our domestic ducks except the Muscovy.

The Mallard has the potential for tremendous variation in size and colour, yet it is humankind that has seen fit to exploit this to develop the multiplicity of domestic ducks. This may even be fairly quick to achieve. The Rev. Dixon described his attempts to breed wild ducks. The eggs were taken from a wild Mallard’s nest and hatched under an ordinary duck.

Until a month old, we ‘cooped’ the old duck, but left the youngsters free. They grew up invariably quite tame, and bred freely the next and following years. There was one drawback however. Although not admitted when grown to the society of tame ducks, they always, in two or three generations, betrayed prominent marks of deterioration; in fact, they became domesticated. The beautiful carriage of the Wild Mallard and his mate, as seen at the outset, changed gradually to the easy, well-to-do, comfortable deportment of a small Rouen, for they, at each generation, became much larger.

Their wings no longer crossed over the rump in a ready flight position, but dropped down at their sides like the larger domestic ducks.

Classic Ducks

During the course of this book we will refer constantly to two kinds of domestic duck: the ‘classic’ and the ‘designer’. We make no apologies for such coinage: the terms refer to very different forms of development, as we will try to explain.

The ‘classic’ ducks are typically those featured in the earliest books of waterfowl standards and those still tending to win most prizes in major exhibitions. They include the Aylesbury, Cayuga, Pekin and Rouen, in the heavy breeds, as well as the Bali, Black East Indian, Call, Hook Bill, Indian Runner and the Crested Duck, in the lighter varieties. What is special about these birds is the nature of their evolution compared with the more deliberate engineering of the later ‘designer’ ducks. Classic ducks evolved in different geographical areas over what may have been long periods of time. They were developed in some cases for meat, like the white Aylesbury with its clean-looking carcass, large body and light-coloured meat. They were also developed as economical foragers, like the so-called Indian Runner that gleaned its food from the padi fields of Indonesia and was famed for its prodigious egglaying. They were developed as Decoy Ducks, the alternative name for the Call Ducks, because of their portable size and loud quacking, which brought wild ducks down to the guns of wild-fowlers or into the mouths of great cage traps (koys). Each ‘breed’ of duck had a very special pool of genetic material. Until the nineteenth century it is very unlikely that the last three mentioned birds were ever ‘live’ in the same continent together, let alone the same collection. They were unique simply because they were not mixed.

Fig 3 The Muscovy Duck, Anas moschata. (Illustrations from Willughby, 1678; photocopy; by permission of the British Library)

Although based on the same ancestor, the birds evolved in different geographical areas because of the limitations of human travel. As long as it took months to journey to China by horse, camel or sailing ship, there was little chance that voyagers would bother carrying anything so trivial as a duck, apart from the odd dinner. It is only when transport became easier and the Western nations began to open up their empires all over the globe that an interest in exotic waterfowl really ‘took off. Until then the British slowly developed their Aylesbury; the French developed a parallel form in the Rouen; the Chinese produced the Pekin; and the archipelagos of South East Asia concentrated on the perambulatory egglayer, the Indian Runner Duck. These bird populations were largely restricted to distinctive gene pools because of the original travel problems.

Fig 4 Pekin drake. The property of Mr F. A. Miles: first prize Crystal Palace 1910, etc. (The Feathered World, 23 June 1911)

Whilst global contact was limited, the ancient duck populations of Indonesia and China remained relatively isolated from Western culture. Exotic specimens were a rarity and usually arrived back in Britain stuffed, skinned or preserved. However, during Victorian times there was a transport technology revolution, which accompanied the manufacturing revolution, so that journey times were shortened and it became more likely that livestock would survive long journeys back from the Far East. The Dutch and British had also established their colonies and trading posts in Indonesia, Malaya and India giving the West the contacts to bring these new breeds home. The American trade with China and Japan resulted in the USA importing live birds from the Far East, including Chinese and ‘African’ geese as well as the Pekin duck. The more affluent cultures of the West with their Victorian mania for collection and cataloguing were not only interested in the birds for their commercial potential; the new imports also caused much interest in their novelty and aesthetic appeal. So although the Pekin did revolutionize the duck industry in both Britain and America, the imported birds were also of interest at a show.

It was in Victorian times that the idea of the show or exhibition actually began. The show was for entertainment as well as a shop window for agricultural produce. Initially the show duck was just a carcass; the dressed duck was all that was on exhibit, amongst the goose and chicken carcasses in the poultry section. However, as the era progressed, so did the number of breeds. The Aylesbury competed with the Pekin in the commercial world and the Rouen was also developed as a heavy duck. The Indian Runner arrived as a novelty egg-layer, probably at considerable individual expense. Call Ducks and Black East Indians were noticed as new and unusual ducks. Why show them dead? These breeds had not only commercial but aesthetic appeal, and the idea of showing valuable, newly imported breeds alive took off after the first show of feathered exhibits at the Crystal Palace in 1845. Classes were provided for:

•

Aylesbury or other white variety duck;

•

any other variety duck;

•

common geese;

•

Asiatic or Knob Geese;

•

any other variety geese.

The idea of the duck, goose and chicken as an exhibition bird and hobby began to replace their original image as a meal.

Designer Ducks

Almost as soon as the imported ‘classic’ ducks reached Europe they were mixed with local blood lines. Indian Runners in Cumbria were crossed with farmyard birds until their carriage was half-way between the vertical Runner and the horizontal Aylesbury. The Americans too crossed their own Aylesbury with newly imported Pekin; as a result the standard American Pekin is still much less upright than those coming from Germany. Although there was a danger of contaminating the purity of the imported blood lines, it was soon found that there were serious advantages. Completely new gene pools were merged, allowing greater variety of shape, size and colour. There was an influx of vigour common to many hybrids and an opportunity for people to create their very own breeds. The late nineteenth century opened the flood-gates of innovation and experimentation. Those breeders who could stabilize a pattern or colour were able to claim celebrity status, especially if they could make capital on the hybrid vigour that certainly gave a boost to the egg-laying production. Basically, the situation at the turn of the last century was one of playing with the new genes rather than genetic engineering in the modern sense.

There is also the chance to ‘customize’. If you have a sufficient range of varieties, it is always possible to plan the next generation of waterfowl. By mixing an egg-layer with a table bird, then crossing it back to another variety, you can develop a multipurpose variety or one with even more extreme capabilities in the table or egg department. By concentrating also on the colours of the birds you can also end up with something both unique and surprising.

It does not take a great leap of the imagination to appreciate the ‘glory’ attached to having a breed named after you. It is almost as good as having a country, Rhodesia, for example, or America, Bolivia or Colombia. The Victorians particularly loved that aspect of notoriety; that is partly why they scattered named grave-stones so liberally around the countryside, and even named their trout flies ‘Greenwell’s Glory’ or ‘Wickham’s Fancy’. Create a special new breed of ducks and immortality is yours … at least if you are called Campbell, or live in Orpington or if your farm is called the Abacot Duck Ranch!

The ducks developed from the crossings and recrossings of the new imports, especially the Indian Runners and the Pekins at the end of the nineteenth century, are what we have chosen to call the ‘designer’ ducks. You will notice that most of them have been classified in the show programmes as ‘Light Ducks’. This tends to indicate an egg-layer or general purpose bird derived from the Runner. They include the Abacot Ranger, the Campbell, the Magpie, the Orpington and the Welsh Harlequin. The later ‘heavy ducks’ have often got more than a trace of Pekin in their make-up. They include the Blue Swedish, the Saxony and the Silver Appleyard. These are just the ones standardized in Great Britain and should also include the two small breeds originally named after Reginald Appleyard.

Fig 5 William Cook’s new breed: a Buff Orpington duck and drake, bred and owned by Mr Gilbert. Each first at the Dairy and the International at Crystal Palace 1908. (The Feathered World, 1908 Vol. 39, No.1015)

Part 1

Breeds of Ducks: History and Characteristics

1 Classic Ducks: The Old Established Breeds

The Hook Bill

The Hook Bill was mentioned in Willughby’s Ornithology of 1678:

… as very like the common duck, from which it differs chiefly in the bill, which is broad, somewhat longer than the common duck’s, and bending moderately downwards, the head is also lesser and slenderer … it is said to be a better layer.

This description was written well before the acceptance of the Aylesbury or Rouen. William Ellis, in The Country Housewife’s Companion (1750) wrote:

The common white duck is preferred by some, by others the Crook-Bill [Hook Bill] Duck, some again keep the largest of all ducks, the Muscovy sort; but the gentry of late have fell into such good Opinion of the Normandy [Rouen] Sort that they are highly esteemed for their full Body and delicate Flesh.

The Hook Bill was found in the Netherlands, Germany and in the old Soviet Union, and was reported by A. Buhle (1860) as being widespread in Europe but particularly in Thuringia, where it was kept on garden ponds for its delicious meat and egglaying capabilities.

Schmidt (1989) says that Durigen referred to the breed as Haken-oder Bogenschnabel Ente (Hook- or Bow-Bill Duck), Anas domestica adunca, where the shape of the beak is more down-turned than that of the domestic duck. The Hook Bill may have been created so that it could easily be distinguished in flight from the Mallard. Hunters could then refrain from shooting the birds on their way home at night when the wild Mallard were culled. However, to make their quick identification in flight more certain, the White-Bibbed Hook Bill was also created.

Harrison Weir wrote that the breed was said to be of Indian origin. The Dutch Historian van Gink (1932) also said that they were from the Far East and there is acceptance in Holland that the most likely place of origin is East Asia, from where they were taken and brought to the Netherlands by Dutch seafarers in the ‘Golden Age’. K. Broekman (personal communication), who works in the oil industry and has travelled extensively in the Far East, has looked many times for these birds, so far unsuccessfully. One day, he asserts, he will find them if they exist.

Fig 6 Anas rostro adunco, The Hook-bill’d Duck. (Illustration from Willughby, 1678; photocopy; by permission of the British Library)

Hook Bills in Holland

Writing in Waterfowl (1987), Broekman said that Hook Bills were once kept by the hundreds of thousands in the province of North Holland (Bechstein and Frisch, 1791). The Dutch method of keeping ducks did not actually cost anything; this particular duck went off in the morning to the rivers and canals to find food and returned home before dark to spend the night and lay eggs. These domestic ducks were expected to fly quite a large distance to find their own food, so it could not be a heavy duck.

Edward Brown wrote in detail about the Dutch egg-production industry in the Landsmeer district of North Holland, in the early 1900s. Dairy farmers in the area hatched and reared the ducklings but the ‘plants’ where the eggs were produced were highly intensive. The ducks themselves did not show a trace of the Indian Runner type, but were rather small bodied and level from front to back:

Some closely follow the Mallard or wild duck in coloration of plumage and markings. A considerable proportion, however, show a white cravat or crescentic marking across the throat, in which case the plumage is black or very dark. Some specimens with Mallard marking carried a very long bill, which curved downwards – the upper and lower mandibles being alike in this respect. These were reported as most prolific layers.

Brown appears to have seen the North Holland Hook Bills being used as commercial ducks in these intensive farm systems, where the birds were kept in yards bordering on the canals where they had continual access to water. The birds were fed on maize and small fish caught in the Zuider Zee, which were fed live to the ducks and were said to indispensable for the ducks’ diet.

Unfortunately, in more recent times, word was spread that paratyphus (salmonella) was passed on through duck eggs. Broekman comments too that the water became polluted, and five years ago he says (in 1982) there were only thirty Hook Bills left. Many buyers chose to eat poultry meat instead of duck and, at the shows, there was a lot of competition from other ‘ornamental’ waterfowl for, in Holland, wildfowl such as Mandarins are still shown. This small number quoted was the Bibbed Hook Bill with the white heart of feathers on the breast rather than the dark wild colour, which has been crossed many times with other birds (Ringnalda, personal communication).

Broekman also reports that through the efforts of the Dutch Domestic Waterfowl Association the breed is back again in its full glory. At Ornithophilia 1987 (Utrecht) twenty-seven Krombekeenden were on show, and in 1988 the Hook Bill was allowed the ‘introductory process’.

Hook Bills in Britain

Weir (1902) described birds imported from Holland, which were kept on the lake at Surrey Zoological Gardens between 1837 and 1840 when ‘they were the ordinary colours, mostly being white or splashed with red, yellow and brown or grey. The carriage was somewhat upright, and the necks and bodies long and narrow’. He also commented that years after, far better birds were shown at Birmingham; these were white with clear orange-yellow bills, shanks and feet, and had a top-knot towards the back of the skull. They weighed about 61b (2.7kg). These perhaps belonged to Bakers (of Chelsea – see the Black East Indian) who exhibited their Tufted Hook Bills at the first West Kent Poultry Exhibition in 1853 (Hams, personal communication). Wing-field and Johnson (1853) also noted that White Hook Bills, imported from Holland, were the type most often seen.

Fig 7 These North Holland White-breasted ducks are bred to be egg-layers rather than fliers like the Hook Bill. Their bill is also straighter. Some sources claim that the Hook Bills originate from the North Holland Bibbed and although most ‘hook billed’ stock was disposed of, some breeders kept them and bred them in order to create a new breed. This photograph from 1916 shows the trapnesting system used to record how many eggs were laid by each duck and so allowed selective breeding. (Photograph courtesy of Avicultura, September 1994)

The breed must have become rare in Britain; they do not appear to have been mentioned in later show reports. A plea to readers of The Feathered World in 1913 to find the ‘old Dutch Hook-billed duck’ drew only the suggestion of the Muscovy, depicted with a rather hooked end to its bill. The original correspondent patiently produced two sketches of the skull of the Mallard and Hook Bill to illustrate what he meant (Staveley, 1913):

I enclose a rough sketch of the skull of (a) a ‘wild duck’ with a straight dished bill [sic] and high cranium, and below it (b) the sketch of ‘Dutch hookbilled duck’ with hooked bill and flat cranium. The latter breed were common in Holland up to 1870, and were known as ‘everyday layers’. Are they quite extinct? Or could a few be found? Perhaps you have some readers in Holland who could rediscover the old utility breed.

As in Holland, the Hook Bill has had a chequered career. A white variety was kept in the UK at Kew Gardens and a few were kept by Reginald Appleyard in the Mallard colour, or in black(?) with a white bib. A few small, White Hook Bills still survived in the 1940s on a moat round the house on a farm at Metfield Hall (J. Hall). The breed was re-introduced to Britain around 1985 and again about 1993 by Tom Bartlett who brought in the Dutch standard for recognition by the British Poultry Club and BWA in 1997.

Fig 8 The skull of the Mallard compared with the Hook Bill.

Characteristics of the Breed

The Hook Bill is characterized by a slender head with a rather flat skull. In profile, the bill, head and upper neck are curved, approaching a semi-circle in shape. The neck itself is carried vertically. The body has a well-rounded, almost prominent breast yet is long and carried fairly upright at 35–40 degrees. Weights range from 3¾ to 51b (1.8–2.3kg) in the duck and 5–5½lb (2.3–2.5kg) in the drake. Note Broekman’s comment that the birds should not be too large. The modern varieties in Schmidt seem to be restricted to the Dunkel (dark or dusky) and Wildfarbig (natural, wild Mallard) colour, which may also have a white bib. In addition, there is a crested variety. The white variety has been recently re-created on the continent by using the White Campbell in the 1980s when eggs exported from Britain were used.

The British standard also restricts itself to the Dark Mallard, the White, and the Bibbed varieties. The Dark Hook Bill shows ‘dusky’ characteristics, in that the duck lacks the typical Mallard eye-stripes and the bright blue speculum of the secondary feathers. The better continental birds have a rich ground colour and clear pencilling on the larger feathers. In the Bibbed varieties the margin of the bib should be clearly defined. The bib itself is white and is accompanied by two to six white primary feathers.

Hook Bill Characteristics

Colour

Dark Mallard

Drake: green-black head; absence of neck ring; body feathers mainly steel blue; speculum dull brown. Bill: slate green.

Duck: Similar to Mallard but no eye stripes; speculum dull brown. Bill: slate grey.

White Bibbed

Same as Dark Mallard except for white, heart-shaped bib and white outer primaries.

White

White plumage; white or flesh bill; orange legs.

Shape

Slightly upright; medium in proportions; bill strongly curved downwards.

Size

Light: 3¾–5½lb (1.8–2.5kg)

Purpose

Utility egg-layer

Fig 9 Head of a Hook Bill duck exhibited by Richard Sadler, Stafford, in 1998. She shows the almost semicircular shape of the head and neck in profile. The breast has a neat, white bib.

The Aylesbury

Everybody has heard of the Aylesbury duck. Its fame has spread all over the world. Point to a large, white duck in the farmyard and some one will say authoritatively: ‘That’s an Aylesbury!’ But the chances are that it is not Most farmyard white ducks have their origins closer to Beijing than the English town in the Thame valley. If the bird has an orange bill, a smooth breast and stands more than slightly upright, it has Pekin blood in it and is nothing like a true Aylesbury.

The pink-billed Aylesbury was the mainstay of the English duck industry until well into the nineteenth century, when it became the victim of its own success and eventually was little more than a trade name, like Thermos and Hoover. Aylesbury became the synonym for any big, white duck. Then it was ousted in popularity by the influx of new foreign breeds, namely the Indian Runner, which had a phenomenal track record for egg-laying, and the large, cream-coloured Pekin, which could be crossed with the Aylesbury or the Rouen to produce more fertile and vigorous offspring. By the final quarter of the nineteenth century, the real Aylesbury had almost disappeared, whilst its name lived on like a ghost to haunt its virtual extinction.

The Aylesbury Duck Industry

For the interested reader, Alison Ambrose’ book The Aylesbury Duck, published by the Buckinghamshire County Museum, is a fascinating account of the social and economic effects of the duck industry in that area. Even in the 1750s, ‘the poor people of the town are supported by breeding young ducks; four carts go with them every Saturday to London’. It was the buying power of the rich in the capital that provided the market for the industry. The impetus for further growth came with the railway. The railway companies or agents even collected the ducklings (aged six to eight weeks) from the village homes for transport in ‘flats’. These were wicker hampers in which the dressed carcasses of the birds were packed.

Small duckers reared perhaps 400–1,000 ducks a year but large breeders, like the Westons and the appropriately named Fowlers, sold many thousands. The small duckers were the labourers who had saved enough capital to start rearing the ducks, for they generally bought the eggs from the breeders. The stock ducks were kept on the farms where the conditions (for the ducks) were healthier, to promote fertility and hatchability. Many of the eggs were hatched by the cottagers who lived in the town and who had town jobs.

One part of Aylesbury was known as ‘Duck End’ and accounts of it at that time indicate it to have been a slum. It suffered from the cholera epidemic in 1832. This was not surprising because of the sewerage of the town terminating there and the existence of a large number of ducks and other animals, which were kept in the houses and yards of the area. It was so wet that the sewage from the duck ponds in the back yard of one house passed under the floor of the living room, causing the soil to ooze up through the bricks. Ambrose quotes the Rev. John Priest from 1810 to give the flavour of a ducker’s cottage:

In one room belonging to this man (the only room he has to live in) were ducks of three growths, on 14th of January 1808, fattening for the London market: at one corner about seventeen or eighteen four weeks old; at another corner a brood a fortnight old; and at a third corner a brood a week old. In the bedroom were hens brooding ducks in boxes, to be brought off at different periods.

As you can see from this account, the table ducks were not permitted swimming water and were not even permitted out of the ‘purlieus’ of the dwelling house till they were killed. They were fed on chopped, hard-boiled eggs, mixed with boiled rice. This was given to them several times a day and ‘their clamour as feeding time approaches is terrible’. Bigger producers fortunately kept them in sheds covered with barley straw and the birds were fed barley meal and bullock’s liver as well, though the less reputable producers were accused of using horse flesh and even carrion. Fowler’s account (in Wright) pointed out that this intensive rearing was only the strategy employed for producing the table ducks, which were generally killed at about six to eight weeks old and weighed about three to four pounds each.

Yet the days of the specific Aylesbury trade were numbered. After 1890, the increase in demand for ducks was not met by the original producing area, but by large-scale industries, which developed in Lancashire, Lincolnshire and Norfolk. In addition, there was the challenge of the Pekin. These ducks had been imported from China in 1873 and, having no bagginess of flesh on the chest, soon gained favour as a commercial cross.

Exhibition Birds

Whilst the Aylesbury Duck industry was at its peak in the second half of the nineteenth century, the Victorian exhibitions also gave the breed additional prestige. At the first National Poultry Show for live specimens held in the Zoological Gardens in 1845, there was a class for the ‘Aylesbury or any other white variety’ and, soon after that, the major agricultural shows began to include a poultry section in their schedule of events.

Birds intended for exhibition, or egg production on the farms, were reared using methods still more akin to the exhibition breeders today, for care was needed to produce the best. Ordinary ducks weighed only 6–71b (2.7–3kg) at a year old, whereas the heaviest pair exhibited by Fowler at Birmingham weighed 201b (9kg) in the late 1800s. Weighing by the pair was customary at the shows in those days and this led to elaborate preparation. Ducks were fattened to the state of obesity; there are records of birds being stuffed with worms and sausage meat, sometimes with dire consequences, such as death from ‘apoplexy’ in the show-pen.

Fig 10 Aylesbury Ducks bred by Mrs Mary Seamons of Hartwell: cup at Aylesbury 1870 and many other cups and prizes. (Outline drawn from Ludlow’s painting in Lewis Wright, 1874)

In early illustrations of the Aylesbury, such as that of the artist Ludlow in Lewis Wright, Mrs Seamons’ prize-winning pair of ducks did not show a keel. This seems to have been developed as an exhibition feature, so that by the late-nineteenth century there came to be two separate strains of the duck – one for the show-pen and one for the table. This did not always meet with approval. Harrison Weir (1902) wrote that the modern Aylesbury of 1902 ‘has been so much increased, though not in beauty, that it now has the appearance of a body inside a feathercovered skin that is at least a size too big’.

Despite this adverse comment on the exhibition Aylesbury, Weir did concede that the Scottish breeder, Gillies, grew drakes at six months old, which reached 121b (5.4kg). It was this type of bird that was now to dominate the show-pen. In the 1920s and 1930s, Huntly and Son (with their Coldstream type), together with the Westons, won at the Palace Show. New names arrived. Vernon Jackson improved his own Aylesbury strain with the MacBean line from Cornwall in the 1930s and, together with Nick Thomas, these two breeders continued the exhibition line post-war as well. At 85 years old in 2000, Mr Jackson can look back on nearly seventy years with this breed.

Exhibition Aylesburys are huge, oblong-shaped ducks in white plumage. The 1901 standards specify that six-month-old ducklings should not be less than 91b (4kg) for the duck and 101b (4.5kg) for the drake. ‘The second year and afterwards, the duck should equal the drake in weight, and neither should be under 111b (5kg). Anything over these weights to count extra merit.’

Fig 11 White Aylesbury Ducks. The property of Captain Hornby of Knowsley Cottage, 1852. These were selected as typical Aylesburys for The Poultry Book (Wingfleld and Johnson, 1853). They had pink bills, pink shanks and feet. (By Harrison Weir)

Fig 12 The Aylesbury in 1905 for comparison. The Countess of Home’s Aylesbury drake. Winner of the first and challenge cup International (Alexandra Palace) and first and challenge trophy Crystal Palace in 1905. (This was the Coldstream strain.) (The Feathered World, March 1907)

Such a massive body needs strong legs and feet set in the middle to support the weight, but these birds are surprisingly agile for their rather unwieldy appearance – as long as they have exercise. The body carriage is horizontal, with the shoulders slightly raised when alert in a show-pen – a characteristic liked by Vernon Jackson in fit ducks. Aylesburys should not droop down or sag at the shoulders; the bird should be able to manage the keel, which starts on the breast and runs under the body, touching the ground. One should get the impression of an oblong duck that is neither cut away, nor baggy, at the back. The body is so big that the wings have to fold neatly at the sides rather than cross over at the rump.

The head is a very important feature of the exhibition bird. It should measure 6–8in (15–20cm) in length from the back of the crown to the tip of the bill. The top line of the bill is dead-straight and it should join the head smoothly without an abrupt rise to the crown. An old, apt description was that it should look like a woodcock in profile.

Despite being a white duck, colour is important in breeding too. The legs are bright orange, though in Weir’s colour print (Wingfield and Johnson, 1853) the legs are the same colour as the bill. The bill must be ‘as pink as a lady’s fingernail’, a requirement once thought only possible to meet in the Thame Valley, where the river gravel wore off the top layer of skin as the birds dabbled in the river. However, it is now realized that putting gravel in their water troughs, and keeping them away from too much grass and sun, will maintain the desired exhibition colour.

The exhibition Aylesbury is not easy to breed, but some of the reasons for Vernon Jackson’s years of success can be identified. Young, fit drakes without too much keel (which gets in the way for mating) should be used with mature (two- or three-year-old) ducks in the ratio of 2:5. The birds, according to Mrs Seamons too, ‘are very fond of green food and … plenty of room’. Perhaps most telling is Edna Jackson’s quip ‘Half the pedigree is by mouth’. As with all heavy ducks, size and quality is only achieved with attention to diet at all stages of production.

Fig 13 Young Aylesburys at Tom Bartlett’s in 1999. The keel on the breast is well-developed and the underline of the bird is parallel to the ground. The birds have a long, pink, straight bill — essential in this breed. A black bean sometimes develops in the females with age, but should be avoided in the breeding stock if possible.

Aylesbury Characteristics

Colour

White plumage; pink bill; orange legs and webs

Shape

Long, horizontal and deep body, keel parallel to the ground; long bill

Size

Heavy: 9–121b (4.1–5.4kg)

Purpose

Table bird originally; exhibition

Fig 14 Head of an exhibition Aylesbury drake. Paul Meatyard’s winning Aylesbury at Stafford, 1999. The eye is fairly close to the top of the head, but not as high in the skull as in a Runner.

The Rouen

Origins

Rouen, Rhone or Roan: these have all been offered as the breed’s original name. The latter two could easily be the result of mispronunciation or corruption of the more acceptable ‘Rouen’, yet each has a logic of its own. Roan is used to indicate the intermingling of grey and colour so prevalent in the breed. Rhone is, of course, another area of France famous for its cuisine and wines and the term ‘Rhone’ does seem to have been used as a name for the duck in 1815. However, many authors acknowledge that these large ducks were successfully selected in Normandy, hence the name of the regional centre, the city of Rouen. Even in 1750, William Ellis reported that ‘the Normandy Sort … are highly esteemed for their full Body and delicate Flesh; they are great Devourers of Grain…’. In A Treatise on Poultry, Fuller (1810, quoted in Weir) wrote of the Rouen:

The large, fine species that answers so well in the environs of Rouen on the banks of the Seine, on account of its being in the power of its keepers to feed them with earth worms taken in the meadows, and which are portioned out to them three times a day under the roofs where they are cooped up separately.

Fig 15 Richard Waller’s traditional commercial Aylesbury Ducks were recently featured in Poultry World. His birds and the business belong to a family tradition that goes back over 200 years and the ducks still show the huge Aylesbury head and the pink beak, but the rounder and tighter breast of the table strain. His is probably the last of the original Aylesbury businesses. Birds such as these could be used to reinvigorate the exhibition line, which is becoming increasingly difficult to breed.

Weir stated that this indicated that the Rouen duck was ‘merely the wild duck enlarged by domestication and high feeding’. Many of the best Rouens in the south of England had a French origin. He quotes (no reference) that in the period 1800–10:

… ducks are therefore a trade of the coasting captains of this nation (the English) who, in passing to return home, sell again to rich landowners wise enough to reside in their domains. The profit of exporters depends on fair weather and shortness of passage which keeps off, more or less, a mortality among their passengers [ducks].

The author was therefore dubious that the import of Rouen ducks in the 1840s by Bakers of Chelsea was the novelty they made it out to be. One of Harrison Weir’s pictures of the breed (Wingfield and Johnson, 1853) shows the birds to be little different from the Mallard in colour but about three times larger than the Black East Indians next to them in the print, placing them at an estimated 61b (2.7kg). In the same volume, the authors refer to drakes reaching 61b each at only ten weeks old.

The breed was developed to exhibition size and status in Britain. Ludlow’s painting of a Rouen pair in Lewis Wright’s Victorian Book of Poultry shows specimens with less well-developed keels than large birds possess today. The duck is rather dark by today’s exhibition standards and although some double chevron marking can be seen on the flank feathers, the wing coverts remain similar to the Mallard’s.

Characteristics of the Breed

Plumage of the Duck

When looking for a really good bird, there are five areas on which to concentrate: shoulders, wing coverts, rump, chest and head.

Shoulder (or scapular) feathers demonstrate the essential characteristics. The big feathers should have a rich golden brown colour. Depending on the strain, and also the effect of the sun, this ground colour can range from what the standards book calls ‘almond’ to deep chestnut. Within the ‘ground’ should be two clearly defined chevrons of almost black lines. The smaller feathers tend to have a central line surrounded by a single chevron. Above all, these should be clear. The poorer birds will be dark, drab and indistinctly pencilled.

The smaller wing coverts too should be clearly marked, each tight feather being clearly laced to give a ‘honeycomb’ effect. The greater coverts, which overlie the secondary feathers (which carry the blue speculum), should also be clearly marked with distinct bands of black and white.

On the rump, the poorer birds will have simply a dark or fuzzy ‘mass’ of plumage. Good birds will have contrast and clarity in these minor feathers. In the show-pen these qualities stand out blatantly. Look then at the chest. Clear un-blurred markings are the things to go for.

The head is the final key area for colour. Sometimes, Aylesbury blood has crept into the strain. It may have been useful at some time to reinvigorate the breed, add size or perhaps give better ground colour, yet it has had numerous negative effects. It is seen most clearly in the bill colour of the male but also in the female head. She should have an orange bill with a dark saddle extending over the sides and roughly two-thirds towards the tip. Aylesbury blood can add a pink paleness and a lack of saddle. Over the course of a year the bill colour will tend to change somewhat, going quite dark in the summer months, yet a constant, overall slate colour should also be avoided. The head plumage resembles a female Mallard. There should be a dark line that seems to go ‘through’ the eye itself, as well as the broad, dark band that extends from the neck to over the crown.

Plumage of the Drake

The drake’s plumage is beautiful and strikingly similar to that of the Wild Mallard. The rich claret bib on the drake should be a solid and clearly defined patch of colour. Any fine, pale fringe to the feathers is a fault. Young drakes often show this defect when they first grow their adult plumage, but the claret colour often intensifies and the fault clears later in the autumn. The bib’s outline should be clear and sharp, neither blurring into the grey flank feathers nor trailing down towards the leg coverts as in the Silver Appleyard.

Fig 16 Good definition of the lacing on the smaller wing coverts and a well-defined white bar are prized in a Rouen duck. She should also have clearly defined dark pencilling on the larger feathers, seen in the foreground.

Fig 17 Head of a typical Rouen duck showing the Wild Mallard face markings-pale lines above and below the eye, and a darker stripe through the eye. The bill also has the darker central saddle and dark bean.

The standard Rouen drake’s grey feathers should persist all along the flank till they join the black rump. Quite often there are several light-edged feathers in the grey flank feathers close to the stern, but this is regarded as a fault.

Spinke (1928) used the term ‘chain armour’ or French grey where each of the drake’s grey feathers is ‘pencilled’ with wavy lines. This pencilling is quite different from the pencilling on the duck, where the dark lines are concentric in form, following the outline of the feather. In the drake, these dark lines cross the feather (another definition of pencilling). The lines appear wavy and even discontinuous, as if stippled with a stiff paintbrush; they are the standard body feather pattern of the male Mallard.

The back, rump and under-tail cushion are a rich green-black, whilst the tail and primary feathers are a dark brown slate. The secondaries carry the speculum as in the duck.

Size and Shape

Apart from colour, the Rouen also has to have the right size and shape. Wright described the birds as ‘massive’. They must be a big duck in the show-pen reaching 9-lllb (4–5kg) in the female and 10–121b (4.5–5.4kg) in the drake. The long, wide bill must be in proportion to the strong head. The body is long and broad with a deep keel. They are oblong in appearance but when moving in the field have tremendous strength and get about very easily.

Breeding for Colour

In the 1920s, there was a trend for double-mating in the Rouen, described by Spinke in The Feathered World (1928). This meant that two breeding pens were kept One was for breeding richly coloured males with a strong claret breast and no white-edged feathers around the stem. The female counterpart was rather dull but, for the ‘drake pen’, these females were ideal.

The emphasis for exhibition on the chestnut females with sharp, even pencilling, meant that lighter coloured males were used for breeding. It is when drakes are in their juvenile feathers that they are selected as breeders for next year’s ‘duck pen’. This is because a male in his ‘duck feathers’ at ten weeks old shows the pencilling and ground colour of the brightly coloured females that he has the potential to produce.

Fig 18 Feather markings in the Rouen. The larger feathers of the duck show double-pencilling in dark brown on the lighter ground (left). The drake’s feathers also show ‘pencilling’ of a different type. Dark lines go across the feather giving a stippled effect (right).

Exhibition

To produce any pure strain, a certain amount of inbreeding is necessary but this continued practice, which restricts the gene pool, eventually restricts viability. In the 1930s pure exhibition Rouens were becoming very difficult to breed, but they were a favourite at the exhibitions. Show results from the Crystal Palace and the Dairy Show in 1930 included Spinke and Alty, who specialized in this breed for many years.

By the 1950s, Rouens were nearly impossible to reproduce (Jackson, personal communication). Appleyard too commented that the exhibition birds were not very prolific; with continuous inbreeding, the eggs are simply infertile. Import initiatives in the 1970s revived the fortunes of the breed. So, although some of the older breeders do not think that Rouens are as beautiful as they were before 1940, at least they do reproduce. John Hall’s birds dominated the show-pens in the 1980s, a typical duck being illustrated in Roberts’ Domestic Duck and Geese in Colour (1986). Such birds provided the foundation stock for many breeders during that time.

Breeding

Rouens do not usually lay as early as the Aylesbury, which, in a young duck, starts in February. Rouens usually bide their time until March and, quite frequently, these early eggs are infertile. This does not matter to the pure-breed enthusiast. The best Rouens are often hatched from the later eggs laid in late April or May. The disadvantage of hatching late, of course, is that the birds take a long time to mature, so that it is difficult to select the best for retention. Rouen drakes take over twenty weeks to gain complete adult feathers and, after that, they can take a year to complete their size. This is especially true of the exhibition strains.

Fig 19 Breeding-pen of two Rouen drakes and four ducks.

Because of their colour and slower gain in weight, Rouens have never figured in the duckling trade but were traditionally used for the autumn market The early slaughter age of commercial ducklings now means that Rouens are totally uneconomic. They are mainly kept as very ornamental, useful birds in Britain but nevertheless stock should be selected with care. Size and colour should be preserved, and also shape. The standard says the body should be long, broad and square. Certainly birds that look oblong in profile seem healthier than those with over-rounded or ‘roach’ backs. Older birds tend to droop at the shoulders and at the rear but young ones must not have these faults. The birds should be kept fit. Plenty of grass, exercise and a stream will ensure that they breed.

The Rouen Clair

Although this breed may be as old as the Rouen, it has rarely been described, perhaps because it has not been exhibited a great deal in the show-pen. The first official standard in Britain was in 1982, when a number of breeds of ducks and geese, many of which had been in collections for over a century, were finally admitted to the Poultry Club Standard.

This revival of interest in standards was after a period of great difficulties for the exhibitions in the early 1970s. The International Poultry Show and the Dairy Show at Olympia had both closed down, and the devastating fowl pest outbreak of 1971 severely restricted poultry movement. However, following a visit to the Hannover Show by Poultry Club members, the Club set up its own National Show at the Royal Show Ground at Stoneleigh. There was an enormous influx of members – both old and new – which resulted in the Poultry Club administration being kept busy ‘approving, adapting and revising standards to permit these old and new breeds to be classified for exhibition. Happily, waterfowl too figured in this resurgence …’(Will Burdett, 1979).

This resurgence resulted in the British Waterfowl Association producing standards for the newly imported Trout and Mallard Runners, plus the Blue Swedish, Harlequin, Appleyard, Saxony and Rouen Clair. There was also a revival of the Blue and Black Runner standard and the Decoy (Call), a breed that was about to make a huge come back. Burdett further commented ‘… what a wonderful addition a full colour WATERFOWL STANDARDS would make to the list of BWA books!’.

The Rouen Clair Standard

Nobody really knows the true story of how the Rouen Clair was produced in France. Somewhere the Rouen had been crossed with birds that introduced new colours. This could have happened before 1853 when it was spotted that there were two colours of ducks imported from France,

the one with plumage like that of the Rouen, the other a much darker bird, both the duck and the drake being of a very drark brown, almost black, each having a white mark on the front of the neck, but not encircling it

The latter could have been an early sort of Duclair, a white-bibbed, dark bird. There was probably no specific reference to the Rouen Clair until Charles Voitellier (1909) recognized not only the Rouen and the Duclair, but also the Canard de Rouen, variété clair.

It seems unlikely that our modern birds go back directly to this stock. van Gink, writing in The Feathered World in 1933, referred to the ‘new French Rouen duck’ from Picardy:

In France, the Rouen ducks are bred in two colour types nowadays: dark (foncé) and light (clair). The light-coloured Rouen is a new production, bred in order to get a purely utility duck with all the beauty and size of the English Rouen duck

It was a certain Monsieur Rene Garry who produced this new type of Rouen duck by crossing and careful selection … [he] selected the breeding stock, to start with, from ordinary Rouen ducks, as they were found on the farms of Picardy, which are the lighter colour type, the ground colour being of a pale buff, a colour usually called ‘isabel’ on the Continent …

We have carefully studied these light-coloured Rouens at the Paris shows, and liked them very much, but could not get away from the impression that Pekin blood had been introduced into France at some time. The shape of the head is too Pekiny not to be related to this wonderful Asiatic breed and we all know that this type of head was unknown in Europe before the Pekin ducks arrived.

In crossing Pekin ducks into Rouens one gets brownish-black crossbreds which, to a great extent, show the markings of the Duclair ducks, so much akin to the Rouen. We are giving sketches of an almost ideal drake, seen in different ways, showing the deep and broad shape of this variety, and also sketch a winning duck drawn from a photograph, which plainly shows the thick, rather short Pekiny head.

The 1982 standard gave only slightly different weights from Brown’s description, and stressed that the breed ‘must remind one of the Common Mallard – a body long and well developed’. Like the Wild Mallard female, the duck must have the characteristic Mallard eye stripes, and the paler throat. The drake, too, looks like a large Mallard. He has a white collar, which fails to encircle the neck completely, a mulberry bib, typical Mallard-pattern body feathers and glossy green-black rump. Unlike the Rouen, the stern must be white. Both sexes have a brilliant speculum – indigo rather than blue – and the duck is more highly prized if she has welldefined pencilling in the form of a chevron on the larger feathers. Today, the beak colour is similar to the Mallard, an orange-ochre bill with a dark saddle being preferred to grey in the female. The bill is yellow with a greenish tint in the male.

Fig 20 Three outline sketches of the Light Coloured French Rouen Drake. (van Gink, 1931)

Fig 21 Head of a Rouen Clair female showing the typical, but exaggerated, face markings of the Mallard, i.e. the darker stripe of feathers through the eye, and the paler feathers above and below. The throat is paler but these paler feathers do not continue onto the breast. (Heather Birkett, Stafford Show, 1999)

Fig 22 A group of Rouen Clair females. (Tom Bartlett’s, August 1999)

Fig 23 Rouen Clair drake showing typical markings. His white collar almost encircles the neck and the stern of the bird is white. These birds should be large, weighing up to 9lb (4kg). (M. Hicks at the Poultry Club National, 1999)

Utility Ducks

These birds have never really been developed for the show-pen in large numbers. The Rouen Clair has probably always been very variable because it was designed as a utility farmyard type. Because the duck can be made from crosses, this explains its variability and also its rapid growth as a table bird, plus its capacity to lay a lot of eggs. Cross-breeding produces big, healthy ducks, which can be prolific. The breed is perhaps an early ‘designer duck’ – a deliberate or accidental cross that resulted in a useful utility duck. Dave Holderread (1985) notes its variability too, because the duck has long been bred for its utility qualities, not its appearance. His ducks typically lay 170–200 eggs and grow to 7–8lb (3–3.6kg); the largest drakes reach 10lb (4.5kg).

Rouen Characteristics

Rouen

Rouen Clair

Colour

Developed from the wild Mallard

A lighter version of the wild Mallard

Shape

Horizontal; keel parallel to the ground; long and deep body; long bill

Slightly upright (10–20 degrees); long body; little evidence of keel; medium bill

Size

Heavy: 9–12lb (4.1–5.4kg)

Heavy: 6½–91b (2.9–4.1kg)

Purpose

Table bird originally; exhibition

Table bird

Call Ducks

Call Ducks have instant attraction. They have appealing baby features to which we are programmed to respond: round faces, big eyes and diminutive size. Apart from being visually attracttive, Calls can also become very tame. They have an in-built blase attitude towards people. Buy a pair of young Calls, perhaps reared with a large number of other birds that have never received much attention, and they will be rather wild initially. But keep them in your back garden for a few weeks and they will end up quacking at the kitchen door.

Fig 24 Two exhibition-quality white Call Ducks showing the round head, bright eye and short, broad body.

Standard Features of the Exhibition Call

Although people often say to breeders that they do not want expensive show birds, they only want pets, it is the standard features of the exhibition Call, which are difficult to breed, that make it so attractive. The birds have a broad, deep body and when viewed from above (on judging them) the body is short. Any birds that have a long or thin, boat-shaped body are rejected. The legs are set about halfway along the length of the bird so that they usually have a horizontal carriage.

With the round body goes a round head with a high crown, set on a short neck. The large, bright round eye is set nearly central to the face, a bit above the half-way line. This gives the bird its baby-like look. The beak should also preserve the same quality. All newly hatched ducklings have instant appeal because, proportionately, their beaks are smaller in length than the adults, even in Runners. As the ducklings grow, the beak lengthens. In baby Calls the beak is minute, often as broad as it is long in a good show strain. As the birds grow, some of these beaks will lengthen but hopefully some ducklings will become the show birds. The standard bill length is a maximum of 1¼in (3cm) but good exhibition Calls have even shorter bills. More important than the actual length, though, is the proportion of length to width, which should be 2:1. A wide bill appears to be shorter than it actually is. A bill that is set at 90 degrees to the skull will also appear to be longer. Lou Horton (1995) suggests that the symmetry of the head, and the bird as a whole, is better when the bill is set 5–10 degrees lower.

The size of the birds is important too. In Germany, the stated weight of the zwergente