1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

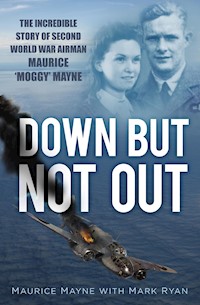

Maurice 'Moggy' Mayne was a cricket-loving air gunner in the Second World War, with a pretty girlfriend back home in rural England. His turret was in a Bristol Beaufort and his pilot had to fly with almost suicidal bravery at giant German warships before releasing the torpedo. No wonder Moggy's first pilot cracked up and his second liked to drink. When he was shot down, Moggy miraculously survived – unlike his best friend Stan. Moggy was sent to Stalag Luft VIIIB, an infamous German POW camp near the Polish border, where he was badly treated. Fearing losing his beloved girlfriend Sylvia forever, and risking recapture and execution, he saw the chance to escape alone, thus beginning an epic journey through Nazi-occupied Germany. As the Gestapo shot other escaped British servicemen, Moggy Mayne came agonisingly close to lasting freedom. Instead, as the war neared its end, he had to face the horrors of the 'long march' west – and he felt his life slipping away. Would he ever see his Sylvia again?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title

Introduction: Nose-Dive

1

Flash of Blade and Thud of Glove

2

The Face in the Window

3

The Boys

4

On Ops

5

The Channel Dash

6

Suicidal

7

Beaufort Down

8

Interrogation

9

Ties

10

Life and Death in Stalag VIIIB

11

The Proposal

12

Meet the Family

13

A Hint of Freedom

14

Berlin and the Coast

15

The Execution Threat

16

Death March

17

Chaos and Salvation

Postscript: Happy Ever After

Plates

Copyright

INTRODUCTION: NOSE-DIVE

1 APRIL 1942

So this was it. The steep dive told me that the pilot, Wing Commander Paddy Boal, had finally selected his target and we were going in for the kill. Pretty soon we’d level out just above the waves, drop our torpedo at the German ship, and turn for home.

These were the seconds that mattered. As a gunner in the turret of a Bristol Beaufort, you had long periods of inactivity. Then suddenly all your senses were heightened, your finger was on the trigger of your Browning, and you were ready to do your bit.

We were just off the Norwegian coast, we’d found the convoy after coming down through the clouds and now there was no time to waste.

Even so, this felt like the steepest dive I’d ever been in. Crazy bugger, Paddy Boal. We all knew he’d had too much to drink in the officers’ mess the night before. The word had gone round like wildfire; he’d danced a jig and played the fool in front of his men. He was the boss; he could do what he liked.

Trouble was, our lives now depended on the speed of his reactions, on his ability to have recovered from the booze. How much was still in his system? He seemed to have lost all fear and the extreme angle of the dive was putting a hell of a strain on the aircraft. I’d just heard some of the furniture cracking up front towards the cockpit. Maybe it was a foldaway table snapping or something; but I was more worried about finding something to shoot at.

I loved to open fire, I don’t mind admitting it. I couldn’t wait, but as I looked out of my turret all I could see was thin air. At the back of the plane, coming down at this steep angle, I couldn’t find a target. It was frustrating; but when we levelled out, I’d be ready to hit those Germans with everything I’d got.

What I didn’t know was that we weren’t going to level out. Those sounds like cracking furniture had been shells coming in from that German ship. Paddy Boal hadn’t taken us into a steep dive because Paddy Boal was dead – hit by a shell, straight up through his seat. The plane was out of control, we were about to slap into the freezing sea.

If I’d known, I might have had time to wonder why the hell I’d stayed as a gunner, when I’d finally been given the chance to train as a pilot. There might have been a few seconds to wonder why the friendships I’d made among my fellow gunners and wireless operators had meant more to me than the chance to control my own destiny. There might have been a moment to say goodbye in my head to Sylvia West, my girlfriend down in Devon, and to my family back in London.

Maybe it was better I didn’t know. There were four of us in our crew. One was already dead, another had only seconds to live … and he was one of my best pals.

1

FLASH OF BLADE AND THUD OF GLOVE

I was lucky to be born at all. My dad, George, was a private in the Royal Fusiliers during the First World War. Somehow he managed to survive being sent over the top in the first wave on the very first day of the Battle of the Somme, when about 60,000 men were killed or wounded.

He charged through the shells and bullets and reached the German trenches alone. Later he recalled:

Out of breath and to gather my wits and strength, I dropped into a shell hole just in front of the German wire. I peeped over the edge, fired a shot at a round hat on a German head that suddenly appeared, rushed the last few yards and jumped into the German trench. I saw nobody there, friend or foe. It was very eerie but I recall facing our old front lines and being appalled at the poor positioning of them. They were absolutely clearly overlooked by the enemy for all those terrible months preceding the battle. Sitting ducks we must have been, I thought.

I then went on to the second-line trench and jumped in, to see a German soldier lying on the parapet. With fixed bayonet I approached, then I saw his putty-coloured face which convinced me he was mortally wounded. The German brought up an arm and actually saluted me. I understood no German language but the poor chap kept muttering two words: ‘Wasser, wasser’ and ‘Mutter, mutter.’ It took me a minute or so to realise he wanted a drink of water. The second word I could not cotton on to. I am glad to this day that I gave him a drink from my precious water.

The other word my dad’s German acquaintance had repeated was ‘Mother, mother.’ My father felt sorry for him and was never ashamed for having shown some compassion. More than a million men became casualties on the Somme eventually. It was a miracle my dad came home in one piece because most didn’t.

Did he receive a hero’s welcome? Hardly. He couldn’t find any work at all in London for the first few months. Eventually a friend managed to get him a job at the Victualling Yard in Deptford. That was where they used to keep all the supplies for the navy, including the rum. My father found himself working in the department where they used to mix rum with lime. Each day all the workers got a ration of rum, same as the navy boys got, but some blokes didn’t want their ration, so they gave it to my father, because they knew he liked it. My mother said he came home one day in a wheelbarrow.

I was born in Deptford and spent my first few years in that part of East London. But as a youngster I used to go up to White Hart Lane with my dad, to watch Tottenham Hotspur play. We’d walk all the way through the city to North London to get to the matches. And if we were running late, he would literally drag me along through the crowds, to make sure we arrived on time. I remember having the skin scraped off my knees in the desperate rush to the Lane. It didn’t put me off, though; the atmosphere was amazing. Those were the days when we all stood, and they passed youngsters over the heads of the grown men and put them down at the front, where they could have a better view of the match. I loved it.

When I was eight years old I asked my father whether he knew how to attack with a fixed bayonet. He said he did and showed me how to put the bayonet on his rifle, which he still had.

‘See? Like this.’ He demonstrated, sliding the thing down once it was on. But he didn’t stop there. ‘First foot forward … plunge! Twist! That’s very important. Pull it out again.’

Some people think you twisted a bayonet to do maximum damage to your enemy’s vital organs, and that could have been a consequence, but the main reason was that if you didn’t twist a bayonet, you didn’t leave enough air around the metal to pull it out again. The ‘meat’ closed in around the blade and then you were stuck. You’d end up tugging for ages and ages, pulling the body along.

‘Thrust! Twist! Come out again!’ He showed me one last time for good measure. ‘In! Twist! Out!’ He didn’t mind teaching me, even though I was so young. Perhaps he thought I might have to fight one day. In a way he was right.

When I was ten or eleven we moved across to West London – Paddington, to be precise – so that my dad could run his brother’s textile shop. I went to the Polytechnic Secondary School there. By then I wasn’t known as ‘Maurice Mayne’ to my friends. For some reason they called me ‘Moggy’ – and the nickname stuck.

Everyone studied a foreign language at the polytechnic, which was a grammar school. You could choose between French, Spanish or German. I chose German. I don’t know why because it wasn’t as if I thought they’d try to invade us or take over the world. I just remember finding it easier than French. German would prove very useful later on – in captivity and then when I was on the run among the Nazis, having escaped on my own.

I also learned to box at an early age, because the school was big on it. Even though I was only small, I discovered that my fists packed a punch and I was nifty on my feet. Quite a few opponents were surprised to find themselves sitting on their backsides before they could land much glove on me.

They had boxing competitions every year at the polytechnic, and the parents were all invited along to watch. I won the first fight I had in a ring because I went in with my fists flying and overwhelmed my opponent. But the second fight I had at school was very different. I went straight in again, as though I was going to murder the other chap, but I left myself exposed and he got me. I took quite a pasting.

I remember going back to the classroom in a state. Mr Chipperfield, the head of the scholarship class, took a good look at my face. It was still smudged with blood and he said to me, ‘Don’t go in for boxing. It’s not nice.’

It may not be nice but it’s a great skill to have and it came in handy during the times of trouble in wartime. When you’re trying to fight for what’s right in a prisoner-of-war camp and some trouble-maker challenges you, what are you going to do if you can’t back up your words with your knuckles? If you’re on a death march in the snow and you have to rip a man’s coat off his back because you think he has stolen it off your mate, you have to be able to give the culprit a look that tells him he’ll get a fearful beating if he tries to fight for that stolen coat. How are you going to do that if you don’t know how to look after yourself? Boxing’s not nice, Mr Chipperfield said. So what? Life’s not nice sometimes.

After I took that schoolboy beating in the ring, you could say I was down but not out. I carried on fighting, partly because the Boy Scouts were big on it too. I was a Scout in Paddington – 43rd Troop, West London. They held boxing bouts every month and I had the opportunity to box against boys in other Scout troops. I don’t think I ever lost a fight in the Scouts. I was learning more about the noble art every time I fought. I understood where to put my hands by then, to keep them up to protect myself from counter-punches.

As well as boxing and football, I loved cricket too. I was good at it and played for an adult team called the Old Vauxonians. In 1934, at the age of fourteen, cricket gave me a special experience, because I met Jack Hobbs! Imagine the current cricket England captain and attach to him the celebrity of David Beckham. Now you’re getting an idea of Jack Hobbs’ status in British sport at the time. He scored 199 first-class centuries and over 61,000 runs, despite his career being interrupted for five years by the First World War, during which he flew for the Royal Flying Corps. How many runs would he have scored if that First World War hadn’t broken out?

He’d already become a journalist by the time I met him, which hadn’t stopped him from scoring 221 against the touring West Indians in 1933 – in his fiftieth year! All the best journalists worked in London’s Fleet Street in those days, so that’s where I went to find him. I was going to pick up an award for the highest-scoring batsman on the London schools circuit that summer.

I climbed some stairs to his office and before I knew it Jack Hobbs, living legend, was greeting me.

‘Congratulations!’ he said warmly. ‘Keep it up! And remember to keep a straight bat!’

Not only did he give me advice, he gave me a junior cricket bat. It was slightly smaller than the average cricket bat, just right for my age and size. And the best thing was, he autographed it for me too. He wrote his initials on it, which for me in 1934 was the cricket equivalent of being blessed by the Pope.

I didn’t have the heart to tell him I’d only come to collect the prize for a mate called Bert Page. But Bert let me use his Jack Hobbs cricket bat whenever I wanted, and I scored quite a few runs with it too! The Old Vauxonians record for 1936 was played 20, won 11, drawn 7 and lost 2 – so I didn’t do them any harm that year.

I won certificates in other sports too. It sounds like boasting but I’m only telling you all this because it helps to explain why I survived while others died as a prisoner of war. I was naturally athletic, you see – even though I was still short and never did grow much beyond 5 feet 7 inches tall. I’d had plenty of practice at racing around. We lived on quite a busy road and there had been a lot of accidents involving bicycles, so my dad told me I wasn’t having one. I’d started to run everywhere instead, especially from the age of fourteen, when I’d begun to get really fit. That’s how I became such a good all-round athlete. It stood me in good stead for the death marches at the end of the Second World War, when only the fittest were going to survive. It also helped me live into my nineties.

Competition is good for you, it’s lovely. Sport at school really is important. People talk about competition not being important when you’re growing up. The same kind of people say boxing is bad for you. What a load of rubbish! When you grow up what chance are you going to have when it’s dog-eat-dog, if you were never encouraged to be competitive at school?

My father knew all this after what he’d been through in the First World War. Now he was doing everything he could to make his family comfortable and was moving up in the world. But he didn’t want us to be soft. He left his brother’s business in Paddington and opened a textile shop of his own in Bermondsey. It sold all kinds of clothing materials and started to do so well that he opened another one in Peckham. That shop began to do even better.

Leaving school at sixteen, I was still a world away from any life-or-death situations – at least to start with. What was soon in danger was my chosen career. The irony was that I played it very safe and joined an accountancy firm. This went well for a couple of years, until I broke the company’s most prized possession – their calculator. I was swinging it over my shoulder when I dropped it. The boss wanted me to pay for it, which would have taken me at least a year on my wages. So I went to work for my father at his textile shop in Peckham instead.

‘Crack cricketer! I’m in the front row (left) in the photograph.’

My family was very friendly with a lot of Jewish people in the East End of London, because a lot of Jews were textile wholesalers. But not everyone was so friendly towards the Jews. Don’t think for a moment that it was only in Nazi Germany where they had anti-Semitism in the 1930s. There was plenty of anti-Semitism in London too, and there were all sorts of derogatory names for Jews flying around – too terrible to mention here. A lot of people down the East End of London, where they settled, didn’t like them at all. If you’ve lived in a place for a long time and it suddenly changes, you take a dislike to the change, I suppose.

But the Jews were trying to integrate and took up a lot of things that the East Enders thought were their prerogative – such as boxing. They found some excellent boxers among their number. The locals were quite surprised by that. And the Jews had musicians – marvellous musicians – people who really understood music.

I had no problem with the Jews; I liked them. I’m not going to lie, though; you had to be pretty sharp when you dealt with some of them, because when it came to business, well … let’s just say they really were business people! You had to fight hard to hold your own and survive alongside them in business. But overall we got on well, the Jews and I. Business was brisk, life was good.

Then the war started and people started joining up. There was a bloke living round the back of my father’s shop and his name was Ken Reeves. When he was on leave, Ken used to walk past the shop in his RAF uniform, all blue and smart. I saw him a few times and thought, ‘Look at that uniform! I want to look that good.’ I was struck by the sheer elegance of his appearance and the way he carried himself. I watched him go past several times and each time I wanted that uniform a little bit more.

‘That’s it,’ I said to myself. ‘I’m going to be a pilot!’

But I didn’t do anything about it until, one Thursday afternoon in the early summer of 1940, I went out for my lunch break and saw a bunch of blokes on a big area of greenery called Peckham Rye. It was a lovely sunny day and I was there to enjoy the fine weather; but these lads were there for a purpose – they were new recruits under instruction. They wore army uniform and they were learning how to fire a rifle while lain down on the ground. I was stretched out on the grass too; but I wasn’t doing anything useful like they were. Suddenly I got this peculiar urge telling me I’d got to join up. But I didn’t want to join the army like them; none of those blokes looked as smart as Ken Reeves.

I went straight over to Eltham, where they were recruiting in a public house called Yorkshire Grey. I told them, ‘I want to join the RAF.’ I could have added, ‘I want to look like the bloke who keeps walking past my dad’s shop in Peckham,’ but they wouldn’t have cared about that. They were more interested in giving me a quick medical – there and then.

A Scot in a long white coat said, ‘Let’s have a sample of yer watter!’

I worked out what he meant and did this little drop in a jar for him. He looked at it and said, ‘I want a bit more than that, laddie!’ So I filled the jar up. I took it over to him and he looked annoyed. ‘I said “a bit more”; I didn’t say have a damn great piss!’ I was staggered at that sort of language from a doctor.

Despite having had the cheek to empty my bladder, they accepted me – or so I thought. My ‘Notice Paper’ to join the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve was dated 29 May 1940. I’ve still got it. Maurice George Mayne of 175 Peckham Rye, Peckham, London SE15, ‘buyer/salesman in outfitters’ became ‘number 1253284’.

Within a couple of weeks they’d sent me for a full air crew medical over at Uxbridge in West London. When I got there though, I quickly realised it wasn’t just a medical, it was a full-scale interview. They put me in front of a panel of high-ranking RAF officers, who asked me various questions.

‘What do you want to be?’

‘I want to be a pilot.’

There was a collective sigh. Then one officer said, ‘Do you realise that every man who comes in here says he wants to be a pilot?’

I nearly said, ‘Of course they bloody do – you’re the RAF!’ Instead I remained silent.

‘There simply aren’t enough places on the courses,’ said another member of the panel. ‘It would be six months before we could even think about sending you on the training course to become a pilot – and the nearest would be Babbacombe in Devon.’

Six months seemed like a long time. Then one of the officers asked me another question. ‘Did you do any sport at school?’

‘Yes, I love sport,’ I said.

‘Did you do any boxing?’

‘Yes,’ I confirmed. ‘I did a lot of boxing and I was good at it.’

‘That’s settled then,’ said another officer, the debate apparently over before it had started. ‘Air gunner.’

Just because I’d done a lot of boxing, they made me an air gunner. No choice! I suppose they thought a gunner had to be a tough, aggressive type. Anyway, the dream of becoming a pilot was over – for now. ‘At least I’m going to be flying,’ I told myself. I was going to see more than my share of danger, too.

Aged nineteen, I took the oath in Uxbridge on 18 June 1940. It went like this:

I, Maurice George Mayne, swear by Almighty God that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to His Majesty King George the Sixth, His Heirs and Successors, and that I will, as in duty bound, honestly and faithfully defend His Majesty, His Heirs and Successors, in Person, Crown and Dignity against all enemies, and will observe and obey all orders of His Majesty, His Heirs and Successors, and of the Air Officers and Officers set over me. So help me God.

‘I’m still only 19 when I join up.’

‘“Present Emergency” … That’s the Second World War!’

‘Allegiance to the King.’

I wasn’t likely to receive any direct orders from King George VI, was I? It was more about getting me to obey the orders of the officers. Disobey your superior officer and it was like disobeying the king. That was the gist of it. I didn’t intend to disobey, I wanted to do my bit ‘For King and Country’ and I was excited about it, proud to take that oath. It was the beginning of quite an adventure, I can tell you.

2

THE FACE IN THE WINDOW

Britain faced invasion and the Battle of Britain loomed. Despite this critical situation, no one seemed in too much of a hurry to get me into the air, or even into the war for that matter. I was sent home and told to wait for a letter. Eventually, after about ten weeks, that letter arrived and I was told to report to St Pancras station on 4 September and catch a train to Blackpool.

My mother and father and younger brother came to the station with me. There were crowds of people waiting on the platform, photographers too. As a young man you feel such a fool when your parents are there and your mother is making a tearful fuss of you. It’s nice to be loved but it was also a relief to get on the train and sit down, four lads to each group of seats.

I was happy and excited when we set off. I was also in the money because I’d withdrawn £40 from my account to make sure I had a bit of spending power for my first few weeks in the armed forces. We knew it was going to be a long journey and we needed something to pass the time so one of the lads said, ‘Fancy a game of cards?’ Well, you can probably guess the rest before I tell you. By the time we reached Blackpool, I’d lost my £40.

The very first night we were in Blackpool, twenty-six of us were put into a boarding house. The blokes were all getting friendly with one another by then. They weren’t just going to go quietly to bed; this was a seaside town and a potential adventure awaited. Everyone decided to go out into town and they chose the ‘Manchester Bar’ as the place to meet up but I couldn’t go because I didn’t have any money. Another Londoner was in the same situation. It was just the two of us, left in the boarding house while all the others went out. We felt sad, forlorn and foolish – we didn’t know what to do. We were just twiddling our thumbs, thinking of all the others having a great time out on the town when suddenly we saw a solution.

In the corner of the front room we spotted what looked like a Christmas stocking, with some coins in it. I know, you normally find chocolate coins in a Christmas stocking; but these coins weren’t made of chocolate. I’m ashamed to say it, but it didn’t take long to empty the coins out of the stocking and join the others in the Manchester Bar. I promised myself I’d make sure that money found its way back into the stocking as soon as I got luckier playing cards! I’m not sure it ever did, though.

By day, at least, military life in Blackpool involved a strict routine: square-bashing or gym work in the mornings, Morse code in the afternoons. The next day they’d do it the other way round to give us some variation. Lessons in Morse were held in the sheds where Blackpool’s famous trams were housed overnight. I enjoyed Morse code more than drill. It was like a refresher course for me because I’d already learned Morse in the Boy Scouts, along with semaphore. You might wonder why I wasn’t firing any machine guns yet; but officially I was training as a ‘WOP/AG’ – a Wireless Operator and Air Gunner. Blokes were supposed to be interchangeable in those two roles. If you were going to be an air gunner, you had to be trained to work the radio too.

In October we had a photograph taken of our group – Class 1, Squadron B, Wing 5. In that photo I’m sitting down at the very front of the group and I look about as proud and relaxed as it’s possible to look in a military snap. I was a serviceman, I liked this new life, and it showed on my face.

Our time in Blackpool drew to a close before Christmas because you never stay in any one place for too long when you’re training. Suddenly we were sent right down to the other end of the country. That didn’t mean the routine changed, though. At Yatesbury in Wiltshire there was more radio in the morning, drill in the afternoon and vice-versa. We might just as well have stayed in Blackpool, except that it was midwinter by now.

When was I going to be allowed to start firing a machine gun from the turret of an airborne plane? When could I learn the trade for which I’d been earmarked in the first place? We were just getting settled in Yatesbury when it was time to move back up north again. At the end of February 1941, at Catterick in Yorkshire, my new radio skills were at least put to the test in more of a wartime environment. Except that I didn’t have to be very skilful. I had a job based in a caravan just off the base, surrounded by sheep and newborn lambs. There was a fighter squadron at Catterick and they were practising their landings. Where did I come in useful? I’d be in this caravan which had an aerial on top. Camp headquarters would phone through to tell me where to point the aerial. This gave the fighter pilots a fix on where they were supposed to be coming in. But they were training too and there was always the potential for disaster.

One night I heard and felt a terrible twang and realised one of the fighter aircraft had hit the aerial on the caravan. I was just below the collision, right there inside the caravan! It could so easily have been the end of my war, not to mention the flying days of that dodgy pilot. But luckily the aerial didn’t bring the plane down, so we both lived to fight another day. I was happy to hear that my next destination was to be Stormy Down in Porthcawl, Wales. It wasn’t that I had any special connection with Wales; I was just pleased to be leaving Catterick at the end of April before a pilot could land on me.

Stormy Down was where I was going to do my gunnery course. I’ll never forget arriving at the air base. Just inside the gate we saw a Fairey Battle, a monoplane, which had crashed and was still up on its nose. That was the angle it had gone in at by the look of it, so the wreckage looked a bit horrific. I wondered whether they had left the aircraft there as a warning to us, or if the crash had just happened.

The bloke who was driving us into the base in a lorry, a very nice chap, saw us eyeing the crash scene and said casually, ‘That prang happened the other day. Two men killed, including the pilot.’ We went right past the plane, almost as though we were being given a stern lesson in the cost of being careless in the air. Terrible, that was.

My mood didn’t improve when we were told there was so little accommodation that we’d have to sleep on the beach. Were they trying to toughen us up or were they just incompetent logistically? The result was the same. We weren’t billeted anywhere, there were no huts or anything, so we were left to our own devices at night. There were some fairground merry-go-rounds on the sea-front and I slept under one of those every night. A lot of the lads did the same. We’d go into town and have a pint if we could, then down to the beach for the night. It was early spring but the weather was still terrible, so it was miserable being out on the beach. I paddled in the sea once or twice to try to cheer myself up but I never dared take a proper swim there – the water was too cold.

‘Young and proud! I’m in the front row, second left.’

Not having a roof over our heads at all seems a bit of an RAF oversight, looking back. We were issued with ground sheets and a couple of blankets; but basically we were sleeping rough. It was chilly and I got terrible back-ache down there. Still, we were young, we thought we were tough enough to cope with it, and we just got on with it. Luckily Stormy Down offered more exciting things than back-ache too. The first time I laid my hands on the Vickers Gas Operated machine gun (VGO) was on the ground there. I had a bit of instruction on how the weapon worked from a member of the ground staff. Then I went up with a pilot in a Fairey Battle and fired the VGO from the air. I was sitting just behind the pilot and he would point to the aircraft ahead, which was towing a tubular drogue behind it. We got a diagonal angle on it, so that I wouldn’t be shooting my own pilot or firing into the plane dragging the drogue. Then I was given the signal to open fire. The murderous clatter of the VGO was music to my ears. I suppose if a new gunner like me had got over-excited, he could easily have fired into the other plane and brought it down. Fortunately I didn’t do that and I never heard of anyone who did. You had to stay cool and concentrate on what you were doing.

There were a hundred rounds in each pan and so it only lasted about five seconds. Then you had to slap a new pan on top of the breech. So there was a lot to be said for making sure you were economical and accurate with your fire. It was a thrill to fire the machine gun and I was good at it too. You left marks on the drogue if you’d hit it and every tracer had a different colour, so you knew whether you were hitting the target or not by the trajectory of the tracer and the holes you created. I was accurate alright; my pay-book carries a note from my instructor saying ‘very efficient at air-gunnery’.

Inevitably it was soon time to move on to a fresh training centre, one I hoped might even have a bed waiting for me under a roof. My back-ache had become so bad that I needed a couple of the blokes to carry one of my kit-bags out of Stormy Down. I had two huge bags, absolutely full of kit, and I couldn’t carry them both any more. Sleeping rough had taken its toll.

Elated at my success with the machine gun and buoyed by the news that my back wasn’t going to have to get any worse, I moved on to Chivenor, a nice little base in North Devon at the start of June 1941. When we got there, I was the one given the official papers, which meant I was more or less in charge of sixteen other blokes. Trouble was, I soon lost them all. A big group just left the base and went down the pub in Braunton, a few miles away. I booked them all in at Chivenor and then decided to go and look for the ones who had gone down the pub. Just to make sure I hadn’t forgotten anyone, you understand me, because then I’d have been in trouble. It was nothing to do with wanting a beer myself!

I’d walked a fair way on a warm day and I was feeling tired by the time I reached Braunton, so the sight of a park there was very welcome. It gave me the chance to sit down and have a little rest in the sunshine. I didn’t take my shirt off, I had to keep my uniform on, but at least I could relax a bit. There were some houses bordering the park, just across the road from where I was. I looked over and that’s when I spotted her. A face in the window of a house, quite some distance away, looking out towards me. I couldn’t make out her features too clearly at first, but it was a female face, I could tell that much; and that was enough to attract my interest. She looked at me and I looked at her. She looked quite pretty as far as I could tell, but we were so far away from each other, I wasn’t even sure if she was smiling. Still, we both knew our gaze had met, because she moved away from the window when I looked at her. After a short time she came back to the window again, to see if I was still there, I thought. When I looked over again, she moved away once more. This went on for quite a while, like a game of cat and mouse. She’d sneak back, I’d catch her looking over, she’d move back from the window again. It was quite fun, but an older man, who was probably her father, suddenly appeared at another window and that broke the spell a bit. Eventually I had to move on to find that pub and check the blokes were there. It had been thirsty work, that long walk, so I enjoyed a pint with the rest of the lads once I’d found them. For a day or two I thought no more of the girl in the window, because I had plenty to think about at Chivenor.

We discovered we were going to be flying in Bristol Beauforts, quite chunky planes which could carry bombs or even torpedoes in theory. There was nothing very beautiful about a Beaufort, but she had a reputation for being quite a sturdy aircraft. She had two windowed areas jutting out at the front. The main, Perspex nose housed the navigator, who was closest to any land or sea target which might loom below us. But above and slightly behind the navigator was the pilot’s cockpit, which was also surrounded by Perspex windows. Naturally the cockpit contained all the most important controls, and the pilot’s steering column featured a button. Press that and he could drop bombs or a single torpedo if ever we were to be given one.

Behind the pilot, just the other side of a thin steel screen, you had the wireless operator and his radio. He could walk round the screen if he wanted to get to the pilot or down to the navigator for any reason; he wasn’t closed off in his own little room. But generally it was easier to communicate with each other over the intercom. That was especially true for me as gunner, because I was nowhere near the rest of the lads, really. Way back from the other three, much nearer the tail than the nose; that was my domain, in a little machine-gun turret at the rear. It didn’t have its own door from the outside and I had to climb in through a hatch nearer the front with the radio man and the navigator (the pilot had his own hatch and dropped straight down into his seat in the cockpit). Then I’d step through a bulkhead, walk to the back and squeeze into the turret. The two machine guns were on a platform which you could move from left to right or vice-versa using pedals, to give yourself the maximum angle of fire. I realised it was going to take some pretty nifty footwork if I was going to give myself a chance of hitting an enemy plane flying straight across my field of vision. But I relished the prospect of making a difference in my new role. If I could find something worth firing at, I’d be able to blast away from my turret and make the target sorry it had ever aroused my interest. The first priority of course was to miss our own tail, which stretched out below me. As long as the target wasn’t crafty enough to place itself in a position where my own tail was blocking my line of fire, he was going to be in trouble.

Beauforts weren’t very glamorous and apparently they weren’t that easy to fly either. We all tried to make ourselves as comfortable and efficient as we could be in our respective compartments. We’d need a lot more training to make sure our roles and different compartments became one in action – a true team capable of destroying our enemy. But the first thing to do at Chivenor was to sort ourselves into these four-man crews, so that we could begin to gel.

Chivenor was being run by a larger-than-life, twenty-six-year-old Northern Irishman called Wing Commander Samuel McCaughey ‘Paddy’ Boal, DFC. He had flown Beauforts, seen plenty of action, and won a DFC before completing his tour. Paddy Boal was happy to let us ‘crew up’ of our own accord, because that was the typical RAF way. It was as easy as adding two plus two. Crewing up meant I needed to team up with another WOP/AG (wireless operator/air gunner) – and then find a pilot-and-navigator partnership to make up a four-man crew. We were just told to find ourselves other people – and when we got over the shock at being handed this sudden power, we found it was a marvellous process, very informal. What we didn’t realise during this strange ritual was that it could be such a lottery. Indeed this game of chance and how it unfolded might well decide whether you lived or died later.