18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

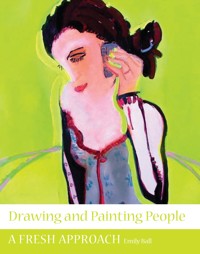

Drawing and Painting People - A Fresh Approach is about confident and defiant art. Written by a practising artist and tutor, it contains inspiring examples, thought-provoking insights and practical advice about how to become more expressive and adventurous with your work. It is a book for people who are serious about painting and want to develop work that is personal and exceptional in quality. An unpretentious, non-academic approach to painting and drawing, which avoids 'painting by numbers' and offers strategies for independent working, building confidence and taking risks. Includes examples from notable artists and is superbly illustrated with colour paintings and black & white sketches.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 270

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Drawing and Painting People

A FRESH APPROACH

Emily Ball

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2009 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Emily Ball 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 184797 788 5

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1.

Mark Making – a Dictionary of Possibilities to Create a Visual Language

2.

Drawing and Painting the Head

3.

The Gaze

4.

The Primitive, the Goddess and the Now

5.

Out of the Ordinary

6.

To Move Forward You Can Look Back and Sideways

7.

Artists in Their Own Words

8.

Open the Door

References

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is dedicated to John Skinner, artist, tutor and friend, for his inspiring teaching and generosity with his experience and passion for painting. He is a fantastic painter who I consider myself privileged to know and work with.

The following people have all also made it possible to write this book: Jane Nash, friend and writer, whose wit and perceptiveness kept me focused on what was important and gave me the confidence to write it in my voice; Gail Elson and Katie Sollohub, who have taught and painted with me for many years – we have shared inspiration, experiences and the highs and lows of being artists together; Katie Sollohub for also being a beautiful model; Georgia Hayes, Roy Oxlade, Rose Wylie and Gary Goodman for their fantastic paintings and wealth of knowledge that they generously shared with me during many conversations; my students, who enthusiastically experiment and take risks with their work and, as a result, encourage and sustain my passion to teach; George Meyrick, who fastidiously and tirelessly photographed all the paintings and drawings; Jeff Hutchinson, who beautifully photographed the artists at work and Katie modelling; Rob Walster at Big Blu Design for his sound advice and feedback about my writing to ‘keep it real’ – just as I would teach it; Seawhite of Brighton (suppliers of art materials and family-run company from whom I rent my studio), where I paint and teach, for their support, vision and belief in what I do; Mum and Dad (George and Lesley Ball): for positively encouraging me to choose a career that was not financially secure and ordinary: and for generally being lovely; Luke, my wonderful and supportive husband; Will and Eve, my beautiful, bright children – my inspiration and motivation to do extraordinary paintings.

For more information about Emily Ball and her work, visit www.emilyballatseawhite.co.uk and www.emilyball.net.

INTRODUCTION

In 1992 I discovered a well-thumbed, plain blue, slim, hardback book written by artist and teacher John Epstein. I was searching for inspiration in the library and on this occasion found a gem. The essays and illustrations within it were the beginning of my understanding of why I find particular methods of working important to me. They felt like a philosophy grounded in something solid and true to my consciousness about creating paintings, but with many possibilities branching off from it.

This was the beginning of my journey to discover what was important to me as a painter and teacher. I incorporated the idea of working with a combination of sensation and observation into my work whilst doggedly pursuing my passion for painting. I then discovered another very important person. This was John Skinner, an artist and teacher who was based in Dorset. John is mentioned a great deal in this book and I have dedicated it to him as a thank you for his inspiring influence and generosity as an artist, teacher and friend. The experience of being taught firsthand by an artist who is so dynamic and eloquent has made a lasting impression on me as an artist and tutor.

During my career I have had the opportunity to work with many remarkable, single-minded people – students, professional artists, writers and teachers – who have been an inspiration to me. They are included in the list of acknowledgements at the front of this book. Some of them feature in the following chapters to illustrate exercises and to demonstrate some possible outcomes of the suggested ideas. As well as illustrations of my work (and that of some of my students who have generously agreed to its inclusion) and the work of John Skinner, this book includes paintings and drawings by Roy Oxlade, Rose Wylie, Gail Elson, Katie Sollohub, Georgia Hayes and Gary Goodman. All of us have taught or still do teach. Many write as an extension of their creative practice or as a tool for critical debate about their work for lectures and articles. Whatever the order in which these activities are undertaken we all practise what we preach, continually testing our theories and challenging our own preconceptions to extend and develop our work. No resting on laurels amongst this lot!

The Purpose of This Book

This book is not intended to be academic, nor is it one that celebrates the usual craftsmanship or accomplished style that many people aspire to attain. I want my own work to be a true and intuitive response to my subject. I have invented, borrowed, adapted and tested many creative exercises to help clarify and unpack the process of creating personal, beautiful and often challenging paintings and drawings.

In this sense this is not a ‘How To’ book, but a book that illuminates the way in which some contemporary paintings appear whilst offering some ideas for unpacking the creative process to enable a greater understanding of the possibilities of painting and drawing. If you feel bored or stuck with your work and want to know how to move forward then this book is perfect for you.

This book is about:

•

celebrating the best that painting can offer (qualities that are sensual, physical, poetic, beautiful and poignant);

•

rigorous, non-fussy, vital painting and drawing;

•

getting rid of the ‘flab’ in your work;

•

stripping away the pretentious, arty, slick cleverness; and

•

giving confidence and courage to artists and students to take risks.

The purpose of painting and drawing for me is to find out what my experiences of the world around me look and feel like, through a painterly visual language. As an artist paints and draws they discover their subject. Each piece of work requires an intuitive and responsive approach. Creating it is a sensual, practical and visual process: one that challenges your preconceptions and conditioned ideas. The artist embraces this challenge, allowing the work to take them in new directions that they could not have anticipated. In doing so the artist is prepared to take a risk, to leave behind the familiar and welcome the unfamiliar.

From the moment we are born we are responsive and search out ways of stimulating our senses. This enables us to discover the world around us, to invent it to suit our needs and, importantly, we find out about our significance and relationship to that world. This need and desire continues for the rest of our lives. John Epstein’s book contains his energetic and direct charcoal figure drawings. The use of the charcoal was searching and gave form to the poise, weight and character of the figure. There are also short essays and one of them in particular has been absorbed into my teaching and philosophy about painting and drawing. It simply states what is obvious, although it is so often under used or even overlooked. It reminds the artist that before any plans or assumptions are made, before any brush is loaded or charcoal is grasped, there is a sensitive and receptive tool attached to the end of each of our arms. This tool can relate its experience back to the artist and it can influence directly the look and feel of the image beyond what the eye can see and the head can imagine:

A montage of hands showing a range of touches.

A picture is made up of marks. It is made by hand.

To understand the mark, the hand must be appreciated.1

The hand:

a)

is not naturally steady

b)

wants to move

c)

wants to touch

d)

wants to hold

e)

wants to dig, to unearth

f)

wants to encompass

g)

wants to fondle

h)

wants to stroke and to rub

i)

wants to pull

j)

wants to pinch

k)

wants to scratch

l)

wants to demonstrate its owner’s nature in its movement, and it wants to stay in contact with hands of the past

m)

when stretched out in front of us, is the furthest part of the body into the world

n)

reaches out and draws in

o)

is the first to touch others

p)

is a divining rod, a blind man’s probe

q)

will unlock the door.

The significance of the hand, in the context of the practical activity of making a painting or drawing and its contribution to the feel and content of the image, cannot be underestimated. Whilst there are now available to us so many different ways of making images that are efficient and seductive in their effects; it is interesting that the hand still seems so important. The reason for this is that the hand reveals the individuality of its owner, its movement, pressure and sensitivity being inextricably linked to the artist’s desires and personality. The drawing or painting will have an integrity and originality of its own revealed through the actions of the hand. For all our sophistication, intellect and technology we are all creatures that respond to and understand the world around us through our senses. The visual sense is obviously one of the essential tools that enable the artist to create images but it is not exclusively the sense that gives the most creative stimulus and information.

‘Drawing and Painting are the Same’

This is true but is not recognized by many students. In this book, therefore, I have not positioned drawing as either something you necessarily do as a preparatory piece for a painting or as something you use to plan with or copy from. Drawing and painting will be ‘side by side’ throughout the chapters that follow. Drawing can:

•

be the beginnings of investigating and studying a subject;

•

be done in response to an ongoing painting;

•

happen during and on a painting; and

•

act as a trigger (but it is never going to be helpful if the desire is to copy exactly).

The Chapters

In all of the chapters there are some or all of the following: practical exercises, creative philosophy, an artist’s work and their thoughts about the process they go through and my own thoughts gained through both teaching and painting.

•

Chapter 1 deals with the visual language of painting and drawing: manipulating it, playing and inventing with it. It introduces the concept of how to combine sensation and observation to create imagery.

•

Chapter 2 is a very practical chapter that should take the scary factor out of attempting to draw a human head.

•

Chapter 3 focuses on the importance of the gaze and expression of a person. This is a good mix of practical exercises and examples of artists’ work.

•

Chapter 4 explores ways of responding to the whole figure, its sensuality and movement, clothed and unclothed. It also discusses the relevance of creating direct and vital images that do not copy a fixed, realistic viewpoint.

•

Chapter 5 looks at the figure used in a context. The space, setting and treatment of the figure reveal the artist’s motivation and interest in their subject.

•

Chapter 6 examines the exciting process of creating work in response to the work of another artist to create new contemporary images.

•

Chapter 7 uses work from each of the artists featured in the book to revisit the many themes that have been discussed. This gives an opportunity to see how the ideas have been applied and to hear from the artists themselves about how they have tackled the work.

•

Chapter 8 concludes the book and prepares you for coping with the ups and downs of working on your own to develop your own philosophy and creative practice.

Truth and Beauty – What is Real

Right from the start of my teaching career I wanted to be a positive, proactive tutor who responds to the needs of the individual rather than teach a particular style. I am interested in finding ways of ‘unlocking the door’ to a creative space for my students. I provide exercises and watch how, through a simple set of moves, students can find themselves completely engaged and respond to the materials and subject. Finding and maintaining this creative space can be a tricky business. All too often a self-conscious state blots it out, returning the work to something safe and predictable. Teaching, for me, is about giving people confidence. I try to unpack the process of drawing and painting using exercises that contain surprises. My job is to keep generating new ways of moving forward to prevent my students from getting ‘stuck’.

The passage I have quoted from John Epstein, about the hand, remains a very important influence even though for me this teaching was not a ‘first-hand’ experience. However, John Skinner did have ‘first-hand’ experience of being taught by John Epstein, and I was curious to know what his teaching had been like and what had made a lasting impression. He emailed me these thoughts:

It was a strong group with a good rapport. John would often turn up with a handwritten piece of writing and hand out copies. I still have a badly kept one about desperation. ‘You only work well when you are desperate…’ He occasionally would do a bit of drawing with a coloured felt-tip or biro. He also got people to talk about their ideas and we once had a slide show of things that people wanted to talk about. I remember showing slides of some late Turner studies; he commented that they looked like the inside of the body. He was always making unexpected connections. A few times we had two models working together. He pinned up a print of a Gauguin painting or maybe a Delacroix and told us how much the models reminded him of this image. Another time the models danced together.

He never told us what to do but I think tried to create an atmosphere in which new things could be found. There was no specific instruction as far I can remember. He was very encouraging and sympathetic and liked new ways of working. The classes were calm but intense. I worked on the floor so that I could get close to the model. I used compressed charcoal and chalk and water. I am not sure how long I attended for, possible one or two terms 1980–81, but these sessions allowed me to really get over some barriers and push forward with my work.2

You Are an Artist

It is more of a challenge to make students aware of the skills they already possess than to give them new skills. Every person has the ability to create great drawings and paintings if they really want to do so. The most frustrating students to teach are those who do not listen, will not take a risk and do not realize that they have so many of their own resources. Like a parent with their child you want them to become independent, resourceful characters who can go out and do it on their own.

Unless one retains a belief in art’s ability to move the viewer and nourish the spirit, then art ceases to be a special kind of activity and becomes humdrum as any desk job.3

The Painting Is the Idea

Much of what I talk about in the chapters that follow concerns ways of either not copying what is in front of you or not following a pre-planned idea of what you think it should look like. It is sometimes a difficult thing to accept that you can just ‘wing it’. Importantly, it needs a shift in our thinking. You are not painting an idea. The painting is the idea. It does not come naturally because we have been used to illustrations and associating a story with an image, to give it meaning, rather than responding to the work purely visually, physically and emotionally.

None of the artists mentioned in this book set out to illustrate an idea that they have about a subject. The painting and the subject become inextricably linked and the artist comes to understand and expand the subject through the painting as it evolves. The artist also specifically creates a visual language to respond to a given subject. The connection and focus is pertinent to the artist and influences the way in which they handle the materials and move in the space of the image.

As an artist I set myself challenges and take risks. As a tutor I encourage my students to do the same. Training and habit seem to impede the process of allowing ourselves a true response to things and our aesthetic censors seem to have very narrow boundaries as to what we perceive to be ugly or beautiful. Refreshingly, though, what I witness frequently in my own work and that of my students is that the best pieces emerge from a procedure of undermining the ordered and ‘nice’. Often when there is a struggle or dissatisfaction, or perhaps boredom, with one’s work, then to challenge yourself aesthetically is an uncomfortable but effective method of pushing you to a new place. The ingredients that are put together to create work of great beauty and presence can be surprising. The final look belies the struggle, the scraping, dragging battle with the paint that created the finished painting or drawing. The viewer is just caught up in the experience of the subject and the paint.

Suspend Your Judgement

Throughout this book I offer not only practical advice about being more expressive and poetic with your work, but I also unpack the stages through which the work goes. The artists whose work illustrates the book create tough and beautiful paintings, but they are not necessarily going to appeal to you instantly or be accessible. This applies when you look at your own work. As you experiment and take risks with your work it will be tempting to return the work to something more comfortable and familiar. Sit with it, work a little harder, consider how it makes you feel, let it wash over you, walk away and then come back again. You have to get past the first reaction that might challenge your aesthetic taste. Good taste is a dubious quality. Rose Wylie described it well when she said to me, ‘I find good taste, as it’s often ignorantly used, very questionable. Usually, it is taste that simply confirms the opinions of the speaker.’4

John Skinner also feels that students and the public alike might widen their definition of what a painting could look like and how it can affect the viewer:

If people want to gain more understanding of painting, they have to work harder at it. Most people like the kind of art they liked when they were thirteen, that dreadful, nostalgic, prepubescent roses-round-the-door stuff. They want the certainty that young children want, whereas adult art is much more sophisticated. As an adult I want to see and produce proper, grown-up art with a full range of meaning. Proper, grown-up painting has layers of meaning – like a Nereid getting in a car. [Illustrated in Chapter 7.]5

Close and Personal

I have deliberately referred to the artists by their full name and first name rather than the more conventional and formal procedure of using just their surname. This is because I am not attempting to articulate a contemporary critique of their work, I am instead shedding light on their working practice and their motivations for working. Unconventional paintings require an unconventional way of discussing them. I am also one of them, a painter, not an outsider looking in. I empathize with and share many of their philosophies and passions. The tone of my writing is thus deliberately personal. I want the reader to feel that the artists are sharing their thoughts.

In fact, this whole book is about sharing and inspiring others to paint. I am pleased to be able to celebrate all the work of the contributing artists. This book is also about how fantastic people are: their characters, their generosity, their striving to find beauty and significance in the things that they do and see. Writing this book has made me reflect on these special people and the times that have helped me form my particular methods and reasons for painting. It is interesting that for me the affecting experiences have been the thought-provoking, rigorous exercises and the passion of the people who have taught me, worked with me and inspired me. Their positive energy, and their ability to reinvent, to move forward and – so importantly – to have a sense of humour, have been a great inspiration to me.

A montage of marks being made.

CHAPTER 1

MARK MAKING – A DICTIONARY OF POSSIBILITIES TO CREATE A VISUAL LANGUAGE

What is the Purpose of a Mark-Making Exercise?

Mark making is an essential tool, without which no work can be created. Creating an exercise around this means that you make marks on a piece of paper, using your chosen materials, not to create an image but with the intention of limbering up hand, eye and brain as you make contact with the tools, materials and sensations. You should seek as much variety as possible in the marks that you make. It is a reminder and refresher for yourself about the activity in which you are preparing to engage; rather like a musician might do their scales or an athlete warm up and gently stretch their muscles in preparation for the task ahead. It is about making a ‘dictionary of possibilities’ and investigating the versatility of your materials to enable you to create individual and poignant paintings.

All artists desire to be more articulate and inventive as they work. How to avoid those ‘stuck’ moments is a frequent request of both students that I teach and artists that I work alongside. Mark making offers the possibility to extend and develop your work. Without any subject in mind you are left free to play and focus purely on the language of paint. This freedom encourages you to experiment, take risks, rework things and make visual comparisons. It offers the opportunity to extend your repertoire and address the problem of repeatedly using the same old marks and colours when you work.

As you use your materials you can be conscious of improving the quality, definition and inventiveness of your marks. If you have been inspired by the touch and textures of other artists’ work, or the sensation and shape of things from your experience, then this is an opportunity to test them out and see how they feel using your materials. Respond to the marks. Let them guide you and seduce you, and then invent new marks that can become fresh additions to your vocabulary.

What is a Mark?

A mark can be a single blob, line or smudge done in a very simple ‘one-hit’ action. It can be developed through several moves by repeating the action in layers, in order to emphasize and clarify it. It can have attachments or other types of marks contained or buried within it. These layers and attachments emphasize the character and form of the mark.

Every mark has a direction that leads the eye from one area of the image to another. This direction can also be descriptive of the surface of the subject as it rises, falls, dips, folds or judders; in making the mark the hand travels at a particular speed, which affects the feel and energy of the mark. The quality of a mark also changes depending on the weight behind it, which can involve pressing hard or gently caressing and producing even or fluctuating strokes.

Every mark has a scale in the context of the space of the paper and in comparison to other marks.

Every mark has a surface quality and character given by the consistency of the material that makes it. For example, paint that is applied thickly, straight from the tube, has a sculptural lusciousness. In contrast, thinned paint can have a transparent delicacy. Charcoal that stabs the paper in a staccato fashion will be black and puncture the white space. In contrast, charcoal that has been rubbed evenly onto the surface of the paper, with the hand or rag, and then lifted off gently around the edges with an eraser will create a soft mark that melts into the space of the paper.

Every mark can create a physical response or association, for the artist and viewer, being comparable to a tactile experience or adjective. With this in mind the surface quality can be deliberately manipulated to heighten that experience. (See the exercise ‘The Touchy-Feely Exercise’, specifically dealing with this concept on page 22.)

Every mark has a form. This fact is not always instantly recognizable, particularly in those marks that are simply made or are irregular in shape. Form, in the context of mark making, means that the artist must have a heightened awareness of the shape and structure of the mark. This requires the artist to be positive with their gesture and application of the materials, and to shape the mark more clearly if necessary. In doing so the mark will acquire more personality and the artist will make a stronger connection to it and use it more effectively.

To help the artist with this idea of every mark having a form, they should remember the following:

•

A mark must have a beginning and an end.

•

It must start and arrive confidently.

•

It must be purposeful, searching and define a space.

•

The character of the form is informed by all of the other qualities: direction, scale, surface and ‘touchy-feely’ association.

If you consider and use to the maximum effect all of these qualities then immediately your work will begin to have a strength and presence it may not have had previously. You will also become more aware of the potential in the visual language you have created.

What does a mark do, what is its job?

•

A mark defines a space and leads the eye around the image.

•

A mark can be a big gesture encompassing and condensing many qualities of a subject or it can be a small but important contribution to the visual orchestra.

•

A mark acts like your sense of touch across a surface. When you are responding to a given subject, for example the head, your mark corresponds to a specific sensation of, say, skin. You are deliberately moving the direction of the mark to follow the rise and fall of the face and manipulating the surface quality of the paint or charcoal to give you a tactile feeling that is true to the subject. You continue to build these sensations on top of each other and then each mark meets and combines with other marks. The image is beginning to form.

The challenge is as the work develops, and the number of marks increase and overlap, the picture surface becomes more complex. So it may help to think of yourself as more of a surgeon or a scientist. You can look at something, dissect it, arrange the elements, and focus and experiment purely with the qualities that interest you.

What makes a good mark?

Quite often the best marks come as a surprise. The creation of a successful and useful mark is governed by the way in which an artist attacks or approaches the task. If you can give yourself permission to play, or perhaps even to produce what you have previously decided are really bad/ugly marks, it gives a psychological release: a feeling of anti-preciousness, a method of testing one’s developed aesthetic judgement. As adults our acquired knowledge, expectations, likes and dislikes undermine this engagement with the practical process.

The foreword of Gaston Bachelard’s book Poetic Imagination and Reverie asserts that the distinction between good and bad is of no value: ‘Good taste is an acquired censorship’. The colours and marks that may not be in ‘good taste’, as you experiment and search, may feel out of character for you to make. This can be just the shock to the system that is required to refresh and extend your vocabulary, which is very important to remember when grappling with a new language of marks. Our aesthetic likes and dislikes can hold back the progress and value of the work. ‘Taste’ is a fickle thing and often hides the true desire and meaning of the work.

Is it beyond redemption? Or could it be ‘crap into gold’?7

Many of the freshest ideas, innovations and most exciting work come out of those desperate moments when all seems lost and the artist has to change and relinquish areas of the painting in order to salvage the work. Things get interesting when you consider them to be ‘crap’: there is nothing to lose and anti-preciousness becomes a releasing ingredient. In order to salvage it you have to be positive, inventive, clear and dynamic, and more often than not the end result is better than all the previous ones. The artist has to respond, invent and let go of preconceived ideas.

With this in mind I always encourage my students to keep all their work for at least a year before they ‘file’ any of it in the bin. With my own work I often find that the pieces I dismissed as weird or a mess at the time of their creation often have exciting elements that I pick up on and develop at a later date. I was just not ready to see it at the time because it did not fit with my idea of what I thought it should be like.

Developing the accidental can greatly assist with this process. This involves noticing qualities that have come about through intentional, or random, layering. These qualities are then extended and repeated further. The original mark may grow, by absorbing other marks into it or by being given additional insertions or attachments. The surface texture, for instance, may be the predominant characteristic that you wish to exaggerate. It is up to you to recognize something and develop it to see how it feels.

If you never push this far you never move forward and it does not take long before you become ‘stuck in a rut’. It is hard! This is where many artists give up and lose courage. If we can undermine the lazy, comfortable option and instead find a new sensation with the marks then the reward is a continual reinvention of our work.

What is Mark Making Not About?

The most common causes of ineffective mark making are:

Always using lines. This is a common rut into which it is easy to fall; many students are wedded to using lines. A line is a fantastically versatile mark but if you insist on using it exclusively then ensure the qualities of the line are rich and varied (in terms of their thickness, direction, length, straightness or speed of application).

Having all your marks travelling in the same direction. This is another common habit that can make for a very bland, repetitive feel to the work.

Doing lots of swishy figure-of-eight movements. This is part of the previous pitfall but also leads to a tendency to create patterns and thin, half-hearted inventions.

Doing what you already know about. Try working in a way that feels uncomfortable and unfamiliar. Challenge and build on what you know.

Filling in.