7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Unicorn

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

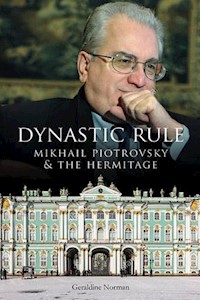

Published to coincide with the centenary of the Russian Revolution in 1917, Dynastic Rule celebrates one of the great success stories of a stormy period of Russian history. This book tells the story of two directors of the State Hermitage Museum, who (for over five decades between them) have presided over what has become one of the greatest museums of the world. Saved from the Bolshevik revolution in 1917, the Hermitage was run from 1964 until his death in 1990 by Boris Borisovich Piotrovsky. His son, Mikhail Borisovich Piotrovsky, took over the reins in 1992; his tenure has recently been extended until at least 2020.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

DYNASTIC RULE

MIKHAIL PIOTROVSKY & THE HERMITAGE

Geraldine Norman

CONTENTS

View from the Victory Chariot on the roof of the General Staff Building, looking towards the Winter Palace

INTRODUCTION

It was February 1993 and I was an art market journalist on a London newspaper, intent on getting to know the post-Soviet art scene in Russia. I had determined that my big piece from St Petersburg was going to answer the question: ‘What has happened to the Hermitage since the Revolution?’

Peter Batkin, Sotheby’s ‘fixer’ in Russia, had promised to introduce me to Mikhail Piotrovsky, the new director of the Hermitage. That was the start of it. Peter, a small, stocky figure who sported stylish black-and-white brogues (of the sort once dubbed ‘co-respondent’1) had previously worked as Sotheby’s chief clerk. He had a gift for finding unlikely solutions, and his Russian assistant, Irina, was similarly talented – it was necessary in the Soviet Union.

We caught the overnight train from Moscow and Peter closed the compartment door and secured it with his belt – against robbers. Irina had negotiated a mini-van to pick us up at the station which contained two bunk-beds and numerous photographs of naked girls. It was in this vehicle that we went to pick up Mikhail Piotrovsky and his wife to take them out to dinner. Peter disappeared to collect them and was gone a long time. He explained later that there had been a murder in the flat below the Piotrovskys’ and Mikhail was concerned that his wife should not glimpse anything as they went out past his neighbour’s door.

There followed a very enjoyable dinner in a casino – the only place, Peter averred, where you could get a decent meal. I talked to Mikhail and found him easy to get on with and obviously highly intelligent.

Mikhail arranged for me to go round the museum with a party from UNESCO headed by Ted Pillsbury, director of the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth. To my eyes, the vast building seemed a Rococo masterpiece; it was only later that I learned it was Russian Baroque. And the art – room after room after room of it – was mostly great and very moving. On the way round I found and bought a booklet of stories recounted by Mikhail’s father to a journalist about the noble and extraordinary history of the Hermitage, and it sowed the seed of an idea in my mind. What about writing a book?

The Hermitage from the Winter Palace to the Theatre

A party from London’s Royal Academy was also visiting – the ending of the Soviet Union had unlocked the marvels of the Hermitage, and everyone was avid to come to see and help. We sat around the table in Mikhail’s office, and the group from the Royal Academy in London explained how a museum can form an organisation of supporters and how they are able to help – the Friends of the Royal Academy is a famously successful organisation; ‘and you want to attract some very rich Friends who will become your sponsors’, they explained, ‘there must be some rich Russians.’ ‘But all the rich Russians are crooks’, expostulated Mikhail. I included his comment in my article, which I duly sent to him for checking. He rang me in London to say that the article was fine but there was one quotation he’d be happier to do without: ‘I’m sure I said it. But it could ruin me’, he said. I agreed to drop it.

I believe that was a turning point in our relationship. I could, perhaps, be trusted. After the article was printed I wrote to him and asked whether he would support me if I were to write a history of his museum. For a year I got no answer. Then we met by chance at the opening press conference of the Maastricht Art and Antiques Fair in Holland. ‘Hullo Geraldine’, he said. ‘I never answered your letter. I’ll just open this Fair, then we’ll find a corner to discuss your idea.’ We did just that and he agreed to help me.

Maybe he had asked some of his museum colleagues about my reputation and had been told not to touch me with a bargepole. I had been writing a series of articles about fakes in the Getty Museum and elsewhere which had not pleased those in authority. He must have wondered how to respond to my letter and decided that the easiest way was not to answer it at all. When he met me again, he made a snap decision. It was madness to let a ‘dangerous’ Western journalist loose in a Soviet museum. Well, it may have been post-Soviet by then but only just. It was a sign of intuitive trust for which I am very grateful.

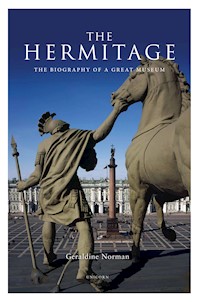

For me, it was the start of a life-changing adventure. I wrote The Hermitage: The Biography of a Great Museum covering the period from Catherine the Great to about 1990, and it was published in 1997. I was then employed by Lord Rothschild to start up the Hermitage Rooms at Somerset House – an exhibition space that ran for seven years from 2000. I started the Hermitage Magazine and the UK Friends of the Hermitage in 2003. And now I have written this book to explain to myself – and hopefully to others –the extent of Mikhail Piotrovsky’s achievements for the Hermitage.

You might surmise from this account that Mikhail and I are friends. But you would be wrong. Mikhail doesn’t ‘do’ friends – he hasn’t time for it. He doesn’t invite them to visit his flat in St Petersburg or the wonderful dacha in Komarovo, on the Gulf of Finland, that his wife has built for him. He attends – and hosts – many, many receptions and dinners in his working life; his private life remains a carefully guarded retreat.

All the same, he is convivial, humorous, good company. What else he is, this book will explore – a born leader, a natural innovator, a clever manipulator, firmly rooted in his family and more widely in his devotion to Russia. Read on …

The arch of the General Staff Building

CHAPTER 1

THE STORY OF THE HERMITAGE

The State Hermitage Museum is the most magnificent gift of the former Soviet Union to posterity – both to Russia itself and to the rest of the world. The imperial collections and the Winter Palace of the Tsars – now home to the museum – were taken over by the Soviet state after the revolution in 1917. Subsequently, nationalisation of great family collections added further masterpieces to the museum.

Some revolutions destroy everything that has gone before, while others deliberately preserve the artefacts of the previous regime so as to demonstrate its wickedly luxurious nature. Happily, Russia adopted the second strategy, so, for example, the magnificent 19th-century Kazan Cathedral in St Petersburg, inspired by St Peter’s in Rome, became (with a few additions) the Museum of Atheism. Religion was out, but there was no destruction of historic buildings or liturgical treasures. On the night of 7th November 1917 when the Winter Palace was stormed by the Bolsheviks, Lenin himself sent a posse of guards to protect the wing housing the Hermitage museum, and both the building and the collection remained.

The Hermitage collection owes its greatest masterpieces to the imperial family, the Romanovs, but its holdings were soon swelled by paintings and decorative arts from the palaces of the Stroganovs, Yusupovs and other noble families. The remarkable Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings that arrived at the Hermitage between 1930 and 1950 hail from the collections of two Moscow textile merchants, Sergey Shchukin and Ivan Morozov.

Before the Revolution in 1917 Shchukin and Morozov had built themselves palaces in Moscow which they filled with extraordinary modern paintings. Shchukin was one of the first collectors anywhere to appreciate the work of Matisse and Picasso. After the Revolution both collections were nationalised and the palaces that housed them were opened to the public. In 1923 the two collections were administratively combined under one title, the Museum of New Western Art. In 1928, both collections were brought together in Morozov’s grandiose mansion on Prechinska Street. But there was not enough space to cram the two collections into one building and some 90 paintings were sent to the Hermitage as an ‘exchange’ for the 250 Old Masters which the Hermitage had been forced to give to the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. Others were rolled up and put in storage in various places and a few were sold. When war struck Russia in 1941 the collection was evacuated to Sverdlovsk in the Urals. The paintings returned to Moscow in 1944, but the Museum of New Western Art never reopened.

The Winter Palace and Palace Square

In 1948 the paintings were dubbed a ‘breeding-ground of Formalist ideas and servility to the decadent bourgeois culture of the period of Imperialism’ and the museum was formally discontinued. The collection was then split between the Pushkin Museum in Moscow and the Hermitage in St Petersburg. Joseph Orbeli, director of the Hermitage, stepped in at this point, sending his wife, art historian Antonina Izergina, to Moscow with orders to ‘get everything you can.’

The Hermitage took the most ‘avant-garde’ because Izergina understood them and was happy to keep them in storage. Over the ensuing 60 years, they were gradually put on show and they now form one of the museum’s main attractions. The Hermitage, with more advanced taste than Moscow, got the bulk of the Matisses and Picassos. Matisse’s paintings Music and Dance, naked figures schematically etched against green grass and blue sky, have been exhibited round the world, becoming something of a hallmark of the museum.

View from the roof of the Winter Palace

In the chaos of the early 1920s, numerous old institutions died out and new ones sprang up. These conditions favoured Joseph Orbeli – a remarkable man, who combined scholarship, charm and a fiery temper – allowing him to create a new Oriental Department. Orbeli amassed a collection for it by scouring first the Hermitage itself and then the rest of the country, helping himself to whatever he liked from institutions and private collections on behalf of the museum. In the space of only ten years it became possibly the most remarkable department in the museum, both for the items in it and for its scholars. Orbeli himself, a future director of the Hermitage, was Armenian by birth and, like Piotrovsky, of noble descent. He never took no for an answer.

In 1941 the Russian Department was added. A collection of some of the finest silver, porcelain, furniture and works of art from former imperial palaces and nationalised private collections had originally been assembled by the Russian Museum, then passed to the Museum of the Revolution (which for a time was located in the Winter Palace) only to be redirected to the Ethnographical Museum which had no space to show it. Finally, in 1941, the collection was acquired for the Hermitage; it comprised some 200,000 items, including imperial clothes and treasures from the Winter Palace that had survived the Revolution.

Henri Matisse, Music, 1910, oil on canvas, 260 x 389cm

The Soviet authorities favoured archaeology, or ‘the history of material culture’ as it was known at the time. As a result, the Hermitage was run by a succession of archaeologist directors, from 1934 to 1990, and became the country’s leading archaeological museum. Archaeology was a crucial part of the museum’s three new departments: the Oriental Department (established 1920), the Department of the Archaeology of Eastern Europe and Siberia (1930) and the Russian Department or Department of the History of Russian Culture (1941). Their summer excavations all over the Soviet Union, on sites dating from Neolithic times to the Middle Ages, have been the chief source of the museum’s new acquisitions since the Second World War. For example, the oldest carpet in the world, dating from around 400 BC, came from a princely tomb found above the snowline in the Altai mountains where very low temperatures had allowed textiles, leather and wood carvings in the tomb to survive in superb condition. The carpet has a sophisticated pattern of knights on horseback and reindeer rendered in only slightly faded blues and reds.

The end of the Second World War saw army brigades dispatched to remove industrial equipment – and art – from Germany as compensation for the havoc that Hitler had wrought in Russia. A range of items from German museum stores and private collections – today referred to as ‘trophy art’ – was shipped to Russia by train. Art from East Germany was returned in a comradely gesture in 1958. Then, abruptly, the Soviets had a change of heart, and the remaining holdings of art from Germany, stored in the museums of Moscow and St Petersburg, became cloaked in secrecy, a situation which was to remain unchanged until after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Mikhail Borisovich Piotrovsky

Following the collapse, the outside world discovered that the Hermitage possessed star collections of Impressionists – first revealed in 1995–96 in an exhibition called ‘Hidden Treasures Revealed’ – not to speak of rich holdings of medieval stained glass, Buddhist wall paintings, Neolithic bronzes, and so on. German efforts to reclaim art moved to Russia in the 1940s continue to this day. However in 1998, legislation was enacted in the Duma establishing that, as far as Russia was concerned, all trophy art was now State property.

Mikhail Borisovich Piotrovsky was born in 1944 while war was still raging. His father was first a Hermitage curator, then Deputy Director, then Director from 1964 for 26 years. The family lived in a building next to the Hermitage, the so-called Reserve Palace – Russian emperors did not have a mere spare room, they had a spare palace. Asked when he first came to the Hermitage, Mikhail replies: ‘When I could walk.’ The apartment where he grew up is currently being converted into storage space for the Hermitage archives, including a memorial room containing his father’s personal archive. As a child, Mikhail attended educational courses at the Hermitage and when he was 20, he gave his first scholarly paper in the Oriental Department on Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra.

For a while in his twenties and thirties, Piotrovsky escaped the Hermitage, studying Arabic at university in St Petersburg and then working at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences (located just 100 metres along the Neva River embankment from the museum). At the same time, he was making trips all over the Arab world, first as a student, then as an interpreter and finally as an archaeologist and scholar in his own right.

The bell tolled to recall him to the Hermitage in 1991 when, following the death of his father, he was appointed Deputy Director. In 1992, when Yeltsin’s new Russia dawned, he was a youthful 48-year-old whose reformist drive was recognised as a positive asset entirely in tune with the times, and he became Director, the fourth archaeologist to serve in this role. (His predecessor, Vitaly Suslov, was a paintings man but he had lasted only 21 months.) Small wonder that Mikhail identifies with the museum in an almost mystical way. ‘The Hermitage is telling me what to do’, he says, ‘it’s not me deciding for the Hermitage.’

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, David and Jonathan, 1642, oil on panel, 73 x 61.5cm

Piotrovsky has now occupied his commanding position at the Hermitage for over 20 years. The museum has spread across Palace Square to incorporate the east wing of the General Staff Building, a magnificent Neo-Classical affair that was formerly home to the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Finance. It contains some 800 additional rooms which he has had no difficulty in filling. Meanwhile a new storage and restoration facility has been built at Staraya Derevnya, on the outskirts of town. This has gradually become a second vast museum whose open storage can be visited by the public.

The Tauride Venus, Greek original 2nd century BC, marble, height 169cm

But it is the globalisation of the museum for which he will be best remembered. There is now a Hermitage Museum in Amsterdam, and there will soon be two more in Barcelona and Shanghai. He had a seven-year flirtation with a branch in London from 2000 to 2007 which finally closed for lack of funding, as did his branch in a casino hotel in Las Vegas, run in partnership with the Guggenheim Museum from New York (2001–07). Within Russia, he has initiated branches in Kazan, on the Volga, and in Vyborg, close to the Finnish border. In 2014 he signed agreements for further branches in Omsk in Siberia, Ekaterinburg in the Urals and Vladivostok on the far Pacific coast.

Scythian gold buckle representing the resurrection of a dead hero, 5th–4th century BC, 15.2 x 12.1cm

Servicing so many outstations presents complex problems of organisation and staffing, but the collection is so rich and so large that it can easily provide for many simultaneous exhibitions. Swelled by the archaeological and Oriental additions of Soviet years, it is now encyclopaedic, offering the opportunity for exhibitions covering virtually every branch of art and artistic endeavour.

Mikhail likes to see his Hermitage as preserving and displaying Russian history – especially the history of the imperial family. With an archaeologist’s sensibility, he sees as a living memorial of cultural history the clothes they wore, the porcelain and silver they ate off and the paintings, jewels and furniture they chose to live with. He also sets great store by preserving the architecture of the rooms they inhabited, believing that showing the collections in a palace environment adds psychologically to their impact and helps the visitor to grasp their significance.

The story of the imperial collections began with Peter the Great’s decision to build a city, St Petersburg, on marshy land around the estuary of the river Neva. In 1703 he had defeated the Swedish army and captured a stretch of coast on the Gulf of Finland, a victory that was of supreme importance to him. He had already built two navies on the landlocked rivers and lakes of his country; now he had access to the ocean. He started by building a fortress on the mouth of the river Neva as protection against Swedish reprisals. This became the Peter and Paul Fortress and formed the base from which he began to construct the city of St Petersburg, forcing his nobles to build new homes there. In 1712, he transferred the government from Moscow to St Petersburg.

Watch on a chatelaine, gold set with rubies and diamonds, designed by Pierre Le Roy, 1740s, diameter of watch 4.7cm, length of chatelaine 18.6cm

His new city was to be a ‘window on Europe’, and Peter himself, after visiting Amsterdam, London, Paris and parts of Germany, began to amass a great art collection. He bought Dutch paintings in Holland, including Rembrandt’s David and Jonathan, a psychologically intense rendering of the parting of the two friends. He bought the work of the best French artists of the day in Paris and had his envoys in Venice and Rome collect an extraordinary group of sculptures, including the Venus of Taurida, a Greek statue of the third century BC which had been dug up in the Alban Hills above Rome. When he failed to get an export license for the Venus, his tireless envoy persuaded the Pope to donate the Venus to Peter in exchange for the relics of St Bridget from Sweden – which were never delivered.

But Peter’s greatest acquisition, from the point of view of the future museum, was his collection of Scythian gold – buckles and ornaments wrought as animals and human figures, stolen by tomb robbers from princely graves in Siberia dating from the 7th to the 3rd centuries BC. He was the first ruler to make grave digging illegal, requiring all gold figures found in local burial mounds to be sent to St Petersburg. The Scythians were a nomadic people, divided into many tribes, stretching from the Danube across Eurasia to Manchuria. Their brilliantly worked gold items were decorated with griffins, wild cats, eagles and many other exotic creatures.

Jean-Antoine Houdon, Voltaire Seated, 1781, marble, height 138cm

Peter established the first museum in St Petersburg – the Kunstkammer – which still exists, although many of its best exhibits have found their way into the Hermitage collection. He built a Winter Palace and a Summer Palace on the banks of the River Neva, as well as several palaces in the surrounding countryside.

It was his daughter, however, Empress Elizabeth, who commissioned the magnificent Baroque Winter Palace that survives today. It resembles a wedding cake, with ornamental clusters of white pillars and white window surrounds contrasting with the pale, olive-green background of the walls. The roof is edged with larger than life-size sculptural figures and emblems that seem as if made of sugar. Designed by Elizabeth’s favourite architect, Bartolomeo Rastrelli, it fills one complete side of Palace Square and dominates the whole.

Besides this architectural masterpiece Elizabeth is chiefly remembered for her jewels. Preserved in the Hermitage Treasury, there are marvellous watches on chatelaines encrusted with diamonds, rubies and emeralds, as well as bouquets of jewelled flowers – pieces that were to inspire Carl Fabergé when he was working there as a restorer a century later.

Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn, Return of the Prodigal, c.1666, oil on canvas, 262 x 205cm

The Winter Palace had only just been completed at the time of Elizabeth’s death in 1762 and it was left to Catherine the Great, the wife of her heir, to furnish it, extend it and give the extension a new name – her ‘Hermitage’. The Russian idea of a Hermitage had been picked up by Peter the Great in France, where Louis XIV referred to the Château de Marly as his Hermitage, a place where he could retreat with his friends, enjoy himself and avoid all the elaboration of court etiquette. Peter built a ‘Hermitage’ in the grounds of his palace at Peterhof where he caroused with his friends. And Elizabeth had a ‘Hermitage’ built at her palace at Tsarskoe Selo. Catherine followed suit when she built the first extension to the Winter Palace and called it her Hermitage; she also used the term for the informal parties she held there away from the spying eyes and ears of servants. There were Petits Ermitages and Grands Ermitages – the grand ones usually including a theatrical performance and a ball.

Catherine was one of the greatest collectors of all time and the founder of the Hermitage Museum. A German princess brought to Russia at the age of fifteen to marry the future Peter III, she had survived seventeen years at court, learned Russian, studied Russian history and converted to the Russian Orthodox faith. The coup instigated by her to unseat her husband was genuinely popular. A week later he was killed by her lover’s brother in a brawl. Her son, Paul I, never forgave her.

Catherine was something of a bluestocking and fascinated by the writings of the French Encyclopédistes. She pursued a long correspondence with Voltaire, acquired Diderot’s library and invited him to St Petersburg. She also tried to persuade Jean d’Alembert, the mathematician and philosopher, to come to Russia as a tutor for her son Paul, but did not succeed. After Voltaire’s death, she bought his library and had a scale model made of the château he had built for himself at Ferney, with the intention of constructing a replica. The marble statue of a seated Voltaire that she commissioned from Jean-Antoine Houdon is exceptional – a sensitive study of an old man, still appearing strikingly intelligent and alive in the last months of his life.

The best pieces in almost every department of the today’s Hermitage were bought by Catherine. She loved the work of Rembrandt and acquired many of his paintings, including The Return of the Prodigal Son, a brilliant study of penitence and forgiveness described by art historian Kenneth Clark, one-time director of the National Gallery in London, as possibly the greatest picture in the world. An enthusiastic billiards player, she hung the Rembrandts round her billiard room the better to appreciate them.

Cameo of Catherine the Great as Minerva by her daughter-in-law, Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna, 1789, 6.5 x 4.7cm

By the time of her death Catherine had acquired around four thousand Old Master paintings, mainly by buying up entire collections. That of Count Heinrich von Brühl, the former Minister of August III, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, brought her four more Rembrandts as well as many other masterpieces, including views of contemporary Dresden painted with almost photographic realism by Bernardo Bellotto. The collection of Sir Robert Walpole, Britain’s first Prime Minister, included works by Raphael, Murillo, Velasquez and a whole array of portraits by Van Dyck. When she bought the collection of 250 antique classical sculptures formed by John Lyde Browne, a director of the Bank of England, there was an unfinished Michelangelo thrown in. The only Michelangelo in the Hermitage, it is a sculpture of a crouching boy digging a thorn from his foot, a great anatomical study quirkily enhanced by having a rough surface as opposed to the usual smooth finish.

Michelangelo Buonarotti, Crouching Boy, marble, height 54cm

But Catherine’s great love was engraved gemstones – cameos and intaglios. She ended up with a collection of some 10,000 of them and encouraged her relations and friends to make new pieces to add to it. Her daughter-in-law engraved a spirited cameo of Catherine as Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, which is among the most popular images of her today.

Antonio Canova, The Three Graces, 1813–16 marble, height 182cm

Gonzaga Cameo showing Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II, 3rd century BC, sardonyx, 15.7 x 11.8cm

Her son, Paul I, enhanced the imperial collection by buying a large group of terracotta models by Algardi and Bernini in Venice and quantities of the best French furniture in Paris – setting a fashion that filled St Petersburg’s salons with delectable works by Carlin and other great French cabinet-makers.

Paul’s son, Alexander I, is still extensively honoured for his defeat of Napoleon. The Alexander Column was placed, in the manner of Ancient Roman victory columns, in the centre of Palace Square, while a Victory chariot, harnessed to six bronze galloping horses, tops the arch opposite the Winter Palace. After riding triumphantly into Paris at the head of his army, Alexander became friendly with the former Empress Josephine. In gratitude for his support, she gave him an incomparable cameo portrait of Ptolemy II of Egypt and his wife Arsinoe II, carved from a sixteen-centimetre oval of sardonyx in the 3rd century BC. Known as the Gonzaga Cameo, it was already famous, having belonged to two of the greatest female collectors of all time, Isabella d’Este and Queen Christina of Sweden. After Josephine’s death, Alexander bought 38 star paintings and four sculptures by Canova from her collection. The gallery where the Canova statues stand is still one of the most arresting spaces of the Hermitage, with its famous Three Graces, depicting lightly draped young girls apparently chattering in each others’ arms.

Alexander’s brother, Nicholas I, added the finishing touches by building onto the palace a museum wing of such extraordinary richness and distinction that it remains a place of pilgrimage to this day. He had been impressed in Munich by the Glyptothek built to house the Greek and Roman sculptures belonging to Ludwig I of Bavaria and invited its architect, Leo von Klenze, to St Petersburg. The only art worth considering at the time were Old Master paintings on one hand and Greek and Roman antiquities on the other. Klenze’s wing housed Classical art on the ground floor in rooms lined with coloured marble or scagliola in a stunning variety of colours and the Old Masters in spacious galleries on the first floor. The arrangement is not like that of a contemporary museum – regiments of paintings hung on a white walls for this is a palace interior, where paintings are mixed with tables topped with lapis lazuli, giltwood chairs, sculpture and elegantly carved hardstone vases.

Nicholas’s wife came from the Prussian court and it was when visiting Berlin that he came across the work of the great romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich, subsequently securing many paintings and drawings by Friedrich and his contemporaries. Moonlight lies on townscapes, and figures are etched against the sky as the seas roll in. This was also the time of romantic dreams of the Middle Ages and Nicholas dreamed and collected, notably ancient arms and armour. A whole arsenal assembled by him was originally housed in the park of his palace at Tsarskoe Selo and later came to join the Hermitage collection.

Left: Leonardo da Vinci, Madonna and Child (the Litta Madonna), mid-1490s, tempera on canvas transferred from panel 42 x 33cm

Right: Leonardo da Vinci, Madonna and Child (the Benois Madonna) 1478–1480, tempera on canvas transferred from panel, 49.5 x 33 cm

The later Tsars paid less attention to art, though Alexander II acquired the best of the Campana collection of Classical Antiquities, which comprised so many Greek vases and marbles that finding room for them required a complete reorganisation of the display in the New Hermitage. He also secured the first painting by Leonardo da Vinci to enter the museum, known as the Litta Madonna (it came from a Milanese collector, Count Litta). In this late painting the peace and serenity evoked by the image of a mother and suckling child is continued in the blue Tuscan landscape glimpsed through the casement behind them.

The Hermitage’s second Leonardo, the so-called Benois Madonna, is, by contrast, an early work. The young mother is playing with her son, holding out to him a four-petalled flower, a symbol of the Cross, which he greets with childish joy. The Benois were a St Petersburg family of architects and artists and the painting had always been known among them as a ‘Leonardo’, without conviction as to its attribution. When it was exhibited in 1908, the Hermitage curator Ernst Liphart recognised it as a genuine work. Nicholas II bought it for the Hermitage at the highest price ever paid for a painting, a record that was not superseded until the 1960s.

Leonardo Gallery with the Benois Madonna in the foreground

That is only to give the briefest, summary history of the Hermitage collection on the eve of Revolution. As already mentioned, it was cherished and expanded in the Soviet period and even survived the depredations of Stalin’s government which, in the 1930s, distributed some of its paintings to other museums, principally in Moscow but also in provincial towns and cities. Realising how straightforward it was to convert paintings from the Hermitage into desperately needed hard currency, the government started to sell some of the collection to international museums such as the National Museum in Washington. It was thanks to the intervention of Joseph Orbeli, who became director of the Hermitage in 1934, that these sales finally came to an end.

While there were sales from every department of the museum, the Old Master paintings sold to Andrew Mellon and Calouste Gulbenkian were the greatest losses and are still mourned today. Mellon’s collection went to found the National Gallery in Washington including such stars from the Hermitage as Raphael’s Alba Madonna, Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi, and Van Eyck’s Annunciation. However there have been no sales since the 1930s and since Mikhail considers such sales as an even greater crime than executing curators on trumped up charges (another feature of the Soviet era), there are not likely to be in future. It was a remarkable collection, combining imperial purchases and extraordinary Soviet extensions, that he took over when he became director in 1992. He also became responsible for some 2,000 staff including around 200 curatorial specialists, each in charge of a specific section of the 3 three million odd items in the collection. It was a city within a city, a state within a state.

Piotrovsky tackled the task as the archaeologist and historian he is. He likes to explain that when an archaeologist runs expeditions, he must learn to manage both his team and the money allocated to him. These are exactly the skills that a museum director must have on a larger scale, and they meant that he at least knew how to make a start on running the Hermitage. The historian, meanwhile, was evident in his dedication to scholarship. He wanted his team to engage in original research, to plan exhibitions to show off the resulting knowledge, to write catalogues of real quality, to contribute to scholarly journals in their fields and to prepare complete catalogues of the items in their charge. Since many curators have charge of collections of 30,000 or more items, their catalogues, often in numerous volumes, have been emerging from the presses for many years.

Burgonet helmet made in Milan, possibly by L. Piccinio, mid-16th century, bronze, gold and velvet, height 26cm

So who was this new director? What was he like? He says now that his experience as an Arabist had given him the confidence of an achiever. He was already someone with a good reputation in his field, and he had sufficient faith in himself to tackle all challenges, relying on his own judgment. He is a good listener and after he listens he decides. He has structured the museum in such a way that he takes virtually all decisions. He has deputies and department heads, of course, but their role, in the main, is to advise him, not to take decisions themselves.

Scythian shield plaque from the village of Kostromskaya c.600 BC gold cast and chased 19 x 31.7cm

He could have chosen otherwise. But he prefers an authoritarian model. Perhaps he knew his staff too well. He had grown up with them. It is a characteristic of the Hermitage that once you are employed there you never leave. You climb gently from intern to junior assistant, to curator and maybe to department head. But you never leave. Those rare individuals who do so are frowned on and considered disloyal. In this way, it is not unusual for several members of a family to work there. When your child leaves school or university you get him or her a job at the museum and they then begin to climb. There are cases of five generations of a family working in the Hermitage, and two or three is considered quite normal.

Piotrovsky cares about this army of employees, cares about them individually, and is extraordinarily loyal. He even looks after them in death. Hermitage staff have their funerals in the Hermitage, with Mikhail himself speaking in most instances.

One curator, who shall be nameless, was talking to me recently about various challenges faced by the museum recently: ‘The Hermitage thinks – or rather Mikhail Borisovich thinks – well, they are really the same thing. I can’t see the difference …’ Mikhail has stamped his image so firmly on the museum that many people can’t tell the difference between Mikhail Piotrovsky the man and Mikhail Piotrovsky the museum. I certainly find difficulty distinguishing one from the other. I doubt if Mikhail himself knows the difference

Naturally, when Mikhail took over his father’s job there were many people who disapproved, who felt that they themselves should have had a turn or that their friend should have got it. The best way to deal with challenges and resentment was to impose his will absolutely. And this he has done.