Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Editorial Bubok Publishing

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

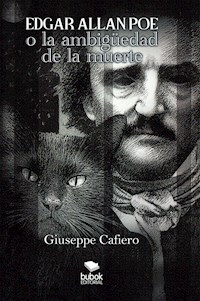

This book is a journey through the life of Edgar Allan Poe, a man wounded by a deep malaise, immersed in alcohol and drugs, at the mercy of an irascible and self-destructive aggressiveness. In order to understand Poe, it is necessary to go to the root of his writing and investigate the essential moments of his life. Thus, Giuseppe Cafiero offers us an analysis of Poe's disturbing writing in the light of conversations with the characters who marked his life and who live in the painful and dark pages of his work. Also, of the friendships and enmities that contributed to the frustrating and delirious restlessness of the great writer.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 254

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

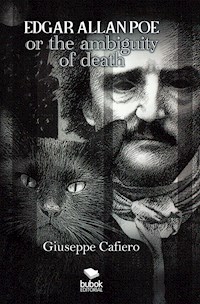

EDGAR ALLAN POE

or the ambiguity of death

Giuseppe Cafiero

© Giuseppe Cafiero

© Edgar Allan Poe or the Ambiguity of Death

Cover illustration: Sergio Poddighe

July 2022

ISBN paper: 978-84-685-6832-4 ISBN ePub: 978-84-685-6831-7

Edited by Bubok Publishing S.L.

Tel: 912904490

C/Vizcaya, 6

28045 Madrid

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing by the Author, or as expressly permitted by law, by license or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Index

PROLOGUE

NOTES FOR AN ACCOUNT OF A LIFE

MS. FOUND IN A BOTTLE, 1833

BERENICE, 1835

THE NARRATIVE OF ARTHUR GORDON PYM OF NANTUCKET, 1837

LIGEIA, 1838

THE FALL OF THE HOUSE OF USHER, 1839

THE MAN OF THE CROWD, 1840

THE MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE, 1841

THE OVAL PORTRAIT, 1842

THE BLACK CAT, 1843

THE OBLONG BOX, 1844

THE RAVEN, 1845

THE SPHINX, 1846

ULALUME, 1847

EUREKA, 1848

LANDOR’S COTTAGE, 1849

PROLOGUE

“Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore”1 was heard in the distance. Thus silence was broken by the rigor of morbid verses. No other breath to comprehend those souls willing to be relegated to obscure omens. Each was what he was, and was determined to seek sensible reasons when, for rash causes or for reasonable motives, he was dragged into a tavern to drink dreadful wines, albeit served well, and reflect upon a man who had received ignominious praise and esteemed criticism and who some time before had been accompanied to the cemetery of the Presbyterian Church in Baltimore so that Rev. William T.D. Clemm, a Methodist pastor, could celebrate an appropriate rite. It was October 8, 1849. A Monday. “Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore” was recited from a distance, or someone thought he had heard those verses.

One member of this small group gathered in the tavern was assuaging his conscience. Another was reflecting upon good and evil, and how good and bad actions could sway his judgment. The third instead was gathering original or spurious knowledge, listening to all the other two had to say, accepting counsel and direction. Resentments as well, long-held and never aged, just as affectionate compassion spurred by the love for a man and his art, because that man had also been a poet.

Best then to find oneself in a tavern to adjudicate, amid healthy or unhealthy beverages, between a man who had an unconscious desire and duty to inquire about the deceased, offering others a series of obscure mysteries so that to someone it might seem legitimate and wise to abstain from tainting his memory, and another man eager for proper or improper knowledge who longed to know about the unfortunate ambiguities of the dead man, a poet who had yielded, both in his writing and in his life, to unjust anxieties and inappropriate inclinations. Certainly that poet had also undertaken tasks superior to his ability in the reasonable desire to understand his longing to antagonize even himself if he could not, or thought he could not, aspire to anything else.

Why die, and not even worthily, in Cooth and Sergeant’s Tavern, there on Lombard Street, next to High Street, leaving unresolved both reproachable and irreproachable inquiries into ambiguous ways of living and other stories? At that time, fools of all sorts and proven ill repute offered free glasses of wine without explaining or even mentioning why, perhaps to facilitate their sinister schemes and nefarious plans. So someone probably wanted him to guzzle liquor to unconsciousness to make him forget facts and actions while the days passed. And the days went by, five of them, without any sense when with urgency and on a promise he determined to take a train that would lead him far away, to a place he yearned for, to forget his worries and embark on a period of intense writing.

Then someone said “dipsomania”. What? And the doctor and man of letters Joseph Evans Snodgrass, present at that gathering of engaging individuals, replied: “An irrepressible impulse to ingest any type of beverage, particularly alcoholic ones, typical of certain mental illnesses. Benjamin Rush first used the term in 1793. Then the Englishman Thomas Trotter. Then Samuel B. Woodward, superintendent of the Worcester insane asylum here in Massachusetts in 1838.”

Why, why? The ancient and bastard game of living and dying, of dying and living without satisfaction or joy, almost out of oblique necessity.

He was treated at Washington College Hospital upon the recommendation of Dr Snodgrass, who had come there through friendship and duty to do what was possible, in his incredible incompetence, to yank from the grip of death someone who contentedly remained there.

And before: it’s true, the irreparable had occurred. In Philadelphia, in that tragic summer when, amid debauches and fits of delirium, he had attempted suicide and was later arrested for raucous, crazy and hallucinating conduct and had to spend a night in the Moyamensing Prison, between Passyunk Avenue and Reed Street.

An unfortunate story, even though that prison was a model of humanity, as the architect Thomas Ustick Walter wished it to be in its various wings, despite its somberness due mainly to its Gothic style set among towers and battlements.

Thus losing the consciousness of a real existence. Invoking phantasms, invoking the living as already dead, yielding to the frenzies of a mortal opiate, attempting perhaps to speak with his other self. Doubling himself. Seeing himself. Killing him who pretends to be what he is not, namely another ignominious self. The madness of a madness beyond time and space, when one is lost in the indolence of prostration, in the comforting essence of therapeutic laudanum with its liturgical and revered mix of opium, sugar, powdered cinnamon and cloves in the fragrance of Malaga wine.

Philadelphia was something else and more: losses and unconscious recoveries. Forgiving when it was necessary. Dr Snodgrass was very generous when speaking to the group. Not so Reverend Rufus Wilmot Griswold who was also there at the Old Swan Tavern in Richmond, unabashedly uttering bitter remembrances. It was he who, in an obituary in the New York Tribune in honor of the deceased about whom he was gossiping, who went by the name of Edgar Allan Poe, had written unjust words, signing them with a pseudonym: Ludwig: “He had, to a morbid excess, that desire to rise which is vulgarly called ambition, but no wish for the esteem or the love of his species”.

Someone then confirmed, with bitter animosity and arrogant manners, the story of ambiguous hallucinations and persecutory delusions so that the editor of the Courier and Daily Compiler, the third member of the group gathered at the table in the Old Swan Tavern, might acquire proper knowledge of something bizarre and worrisome. And this was even more than he desired, he who had asked that a group be convened so that he could hear suggestions and stories about the poet, that is Poe, who had died at dawn, at the H hour, at the time when anyone can unite his essence with that of Jehovah in that primal unity into which everyone is dissolved.

After several earnest interviews and informative encounters, this editor felt the need and the will to write a succinct article in homage to the life of this poet whom he had also in some way criticized, albeit without malice. Indeed, in an article of 1836, when Poe was the sole editor of Richmond’s Southern Literary Messenger, someone from the Courier had written in reference to the Messenger: “the editors must remember that it is almost as injurious to obtain a character for regular cutting and slashing as for indiscriminate laudation.”

Philadelphia, once again. Philadelphia, where some occurrence perhaps brought about the beginning of an inevitable end. It was July 1849 when strange phantasms began to haunt the poet so that the nights were ineluctably filled with thoughts urging him toward violent suicidal acts. He donned ragged clothes and changed his appearance to escape from his persecutors, from the fierce torturers of his own fantasy, even to the point of shaving his moustache. He hid from the oppressors of improper dreams and sought refuge along a river, in the silence of waters marked by the darkness of night.

Glittering reflections of moonlight. The Schuylkill River. The impalpable figure of a woman suddenly began to turn in the air. A woman. Which woman? Perhaps a mother or even a child-wife. An ethereal appearance. Or only a phantasm of the imagination? Flying over the city. Going, taken by the hand by the low susurration of this ineffable figure. Who? Sweet vision, impalpable and dulcet. Going, without any fear since this girl was splendidly radiant. The sky of Philadelphia, also a river and a hundred city lights. Suddenly dark shadows of the mind and strange wishes perverted any guarded imagination and a black bird seized the girl, a rash scream marking the desperation.

“The beginning of the end began there, in Philadelphia”, said Mr Rufus Wilmot Griswold, and he began to whisper: “Ghastly grim and ancient raven wandering from the Nightly shore.”

Then Dr Joseph Evans Snodgrass began to speak with calm and mitigated complacency, observing that it was wise to give a chronological account if one wished to narrate a life. He began by saying that it was best to consider the poet’s ancestry to better understand the story of that short life. Also the obscure and tragic events that had marked the existence of a poet who died not long ago and who left piles of documents with suggestive and ambiguous writings.

“Mere allusions!”, added Dr Snodgrass. But opportune and logical ones when no one, by experience and by improper wishes, had a desire to recall, in a philanthropic mood and without seeking lucrative benefits, a childhood and a youth of that Poe, lost in the memory of years gone by and certainly in miserly wills. It was best, or so it was believed, to conceal all that it was prudent to conceal in deliberate forgetfulness.

In the meantime the Old Swan Tavern had filled with gauche patrons. Clamor everywhere and also some laughter, with no qualms or moderation. Most were drinking, lost in the accounts of colorful lies, above all to forget the fatigue from physical labor and the road dust that chafed the soles of boots and scorched the metal of wagon wheels. Outside a freezing wind chafed the somber faces and hands. Some stood in the loggia sustained by wooden columns, furiously drawing smoke from stinky cigarettes while awaiting delayed acquaintances.

Scattering dust in their path, cabs, coaches and hay carts traversed a tree-lined road filled with rows of thorny bushes. Suddenly was heard the neighing of skittish horses. Black, dun and spotted horses began foaming at the mouth, held by their bits. Wild bridles abandoned in the wind. The blow of the whip to reestablish an order lost in the chaos of hooves and painful whinnying. Then uncivilized screams and blasphemies. A crowd gathered in a jiffy. The former Reverend Griswold, Dr Snodgrass and the editor poked their heads out of an open tavern door. And it was then that, in an instant, they saw a shiny black, diabolical cat steal away with the swiftness of a rat.

A witch then? What was it? Perhaps only terror since its intention was, with balanced fear and incoherent boldness, to avoid a madness narrated by others or simply to attempt to dodge a madness that enraptured and imparted lessons of unusual customs.

Who then could have claimed to possess the legitimacy to criticize, with ordinary notes and confidential reports, the miserable life of a poet some deemed to be despicably disturbing and who had precipitated with reckless folly into a labyrinth of affirmations that were only unusual in the ambiguity of displaying fantasy and very singular observations?

“My tormentor came not. Once again I breathed as a freeman. The monster, in terror, had fled the premises forever! I should behold it no more2 !”, exclaimed Dr Snodgrass and he invited his companions to return to the Old Swan and sit at the table they had previously occupied. Restoring an order full of acceptable, or at least legitimately tolerable, stories, albeit amid petulant denials, composed quarrels, opposing beliefs. The editor was there ready to acquire partial confidences and confidential partialities; it was he who had gathered two individuals on that same day around a dirty table in a Richmond tavern amid healthy glasses of sherry, certainly Amontillado (chosen not only for its mellowness and aroma but also to render worthy homage to Mr Poe and his short story The Cask of Amontillado – but why then not drink the red wine from Chios mentioned in Shadow?). These men, certainly illustrious and of renowned intellectual virtues, were invited so as to express beliefs and thoughts, undoubtedly very different, about this poet and novelist named Edgar Allan Poe who had left a mark, for better or for worse it was said, on the intellectual life of that young nation in the years just passed.

Dr Joseph Evans Snodgrass and former Reverend Rufus Wilmot Griswold had been summoned to answer the eager queries of that editor. Thus he would listen, with painstaking attention and healthy skepticism, to the succession of reminiscences very different in nature even when dealing with a unique event and the same man. Discrepancies, in mark and in value. One of the men, Dr Snodgrass, perceived the unfortunate events that had defined Mr Poe’s cruel life as an inevitable offence of fate against which nothing else could have been done. The other, former Reverend Griswold, did not deem it obligatory, in any way or for any reason, to absolve Mr Poe. He proclaimed that the poet had been offered many valuable opportunities but his innate and presumptuous arrogance had prevented him from leading a modest life and from having the humility to be who he could have been, even if, and this was acknowledged by Mr Griswold without paraphrases or explanations, Mr Poe had (in his own words) “many occasional dealings with Adversity – but the want of parental affection has been the heaviest of my trials3.”

Then Dr Snodgrass began to talk, with no holds barred or untimely hesitations, about Poe’s ancestry. He attempted to speak calmly, despite the frenzy of sherry drinking, saying that it had all begun with Mr Poe’s parents ranging the east coast from Massachusetts to Virginia plying to the best of their ability the trade of being diligent stage artists. They roamed among challenging destinations gaining only miserable wages and various injustices, especially the cruel slander that accompanies the unusual and wretched lives of actors.

Thus David Poe Jr. and Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins, Edgar’s father and mother, found themselves groveling, with their poor art, on a stage that could at least offer a chance for survival. It was 1803 and they were wandering, interpreting their decadent theatrical scenes from Newport to Providence, from Norfolk to Charleston, from Philadelphia to Washington, from Baltimore to the entire state of Virginia.

A surly city, Baltimore. Ferocious? Maintaining order. Above all preventing slaves from fleeing. Also a splendid city of one hundred fifty thousand inhabitants. Majestic churches and splendid monuments. A monument to Washington as well. Thus he surveyed a magnificent white race from a 50 yard-high column surrounded by gardens and vast meadows. Healthy tranquility, broken only by the daredevil escapes. Meanwhile fabulous sailing ships slid by on the channels of the Patapsco. Barges navigated the river bellowing steam. And carriages, carts and coaches ran frenziedly through the confident, lively city. That was Baltimore! Baltimore Street. Baltimore Museum. The Art Gallery. The Merchant Trust Building. The omnibus in Pennsylvania Avenue. Samuel Kirk & Son silversmiths. Carroll Hall. The Emerson Hotel. Phillips & Co. clothiers. The clock on Calvert Street. A very pretty city indeed. A city of wealth where prosperous landlords multiplied their fortunes a hundredfold. Hunting for Negroes, hunting for Negroes. Not missing a beat. Breeding Negroes and selling them to the highest bidder. In the new states in the far southwest. Hunting for Negroes. Reward: one hundred dollars. Two Negroes to be apprehended: Henry Collins and Charles Collins, young and also of polite manner. Or two hundred dollars for a certain Dan, five feet six or seven inches high, very black and stout made, has a scar on his left temple. Or a young Negro named James Hart, rather stout, about five feet six or seven inches high, with a mark on his arm like a leaf. Or Isaac Dorsey, just 15 years old, rather small for his age. Keeping up with escaped Negroes was hard work.

The editor then learned, when Mr Griswold spoke up to rudely interrupt Dr Snodgrass’s speech, that Poe’s lineage was of high origin and confirmed European blood, as well as of apparent respectability ever since one of his ancestors landed on this strange continent. It was John Poe who came to America in 1748 from his homeland: from emerald Ireland, carrying in his genes all the presumed and nefarious peculiarities of his race, above all the fabled reverie and capricious extravagance. John Poe chose to live in Baltimore, in the swampy plain of Maryland on the banks of the Patapsco, a land where in 1749 the “Toleration Act” mandated religious freedom, albeit only for those confessions that recognized the Christian dogma of the Holy Trinity.

It was then, in the sweat of contaminating emotion and in the midst of groggy words, that the group decided to drink another round of sherry, to calm down and better assimilate a past that lived only thanks to mischievous mouths that reported stories that were no longer stories but only gossip and tales having the shameless ambition of being credited as historic memoirs of a life. The life of Poe, who seemed to be famous and thus a source of financial security if one could hastily hold meetings and recount these events to the general public.

A toast as well. And then silence.

It is vile to discredit a lineage in a spirit of duplicitous antagonism and with colorful chronicles. This was the thought of the editor, who thus considered it best to jot down also his feelings and concerns while his two interlocutors were blurting out remembrances too old to be completely true, despite their conviction and facility which rendered them expert conjurers of words and stories. Good people, indeed!

Ancestors that came from faraway lands and became coarsened by frequenting

theaters: this could readily be alleged since there was no one willing to discredit these rumors. How was it possible to give credit to such an ambiguous truth? Strange rumors, those! Whom to trust and why? And if it were true that they had wandered as indecorous actors from one miserable stage to another to gain the applause of a wretched audience, it must also have been true that an itinerant troupe, first called the Virginia Players and later the Federal Theater of Boston, had a very distinguished and well-regarded repertoire. In fact Mrs Poe received enormous praise and authentic acknowledgment, with one critic writing “her conceptions are always marked with good sense and natural ability”. Instead, her husband, Mr David Poe Jr, was deemed a weak actor, lacking in temperament. Nothing, therefore, to be ashamed of or to be justified in the face of the ill-mannered arrogance of those who blatantly drank sherry in the Richmond tavern, who had the effrontery to disparage the ancestry of a man who, miserably and intentionally, had drowned himself in alcohol.

Someone said: “another round!” And there was another round. Of sherry, obviously!

“Tuberculosis”, said another one. And on to another round.

Sherry numbed the mind but helped to fantasize more rapidly about facts and events.

“Tuberculosis!”, someone said forcefully. Was it Dr Snodgrass or former Reverend Griswold? They remained in silence for a couple of seconds ruminating. “A biblical plague!”, someone recalled. Was it Dr Snodgrass or former Reverend Griswold? And it was also mentioned that that plague struck all sinners and descended with “terror, consumption, and the burning ague, that shall consume the eyes, and cause sorrow of heart4.”

And thus the Poes, David Jr. and Elizabeth Arnold, died young. Of tuberculosis. Struck down by the biblical plague? Divine punishment? Hence someone had to take care of the orphans abandoned amid memories of a happy life, albeit spent in the indigence of a sleazy room in the back of a seamstress’ workshop. The date was December 8, 1811.

But by then David Jr. had abandoned his wife and children. “Perhaps he was already dead”, said Dr Snodgrass. A truly horrific and sad story, if it were believable. Was it? Recounting what was learned through unreliable gossip and ambiguous stories. Initially he spoke about Elizabeth Arnold’s first marriage to Charles Hopkins, an actor. Then about how, after being widowed, Elizabeth moved on to a new marriage to David Poe Jr. Later about the children born from their union: first William Henry Leonard, soon to entrusted to his grandparents, then Edgar, born on January 19, 1809 in Boston, and finally an illicit pregnancy of Mrs Poe’s. “Illicit”, muttered someone with malice and a sour gurgle. Indeed Rosalie was born in December 1810 and David had been far away for too long for that baby to be his.

“An indecent death and a shameful life are often accompanied by infamous omens of bad fortune. It is sufficient to read what is written in the Bible, Chronicles II 34: 25; ‘Thus saith the Lord: my wrath shall be poured out upon this place, and shall not be quenched’”. Thus shouted Mr Rufus Wilmot Griswold, as a good former reverend, compulsively sipping a fair quantity of sweet wine.

What did he mean?

A man was at a nearby table full of dirty bowls of miserable soup and large drinking glasses; he was filthy, his clothes torn in various places and grease-spotted, his hands and face scandalously dirty. Inebriated more than ever and barely able to utter words mixed with foamy spittle, he added to the accusation a legitimate and unexpected observation: “The fire! The famous one of December 26, 1811… Seventy-two victims… Who could forget it?”

And he hurriedly drank a nasty greenish liquid from a dirty mug. Absinthe? Christ! But wasn’t it forbidden to sell that horrible anise-flavored distillate made from an infusion of flowers and leaves of Artemisia absinthium which should be drunk with ice water and a sugar cube? I want you to stay sober! A lovely story, indeed! From Tarragona by way of the Spanish Antilles, smuggled, overcoming any prohibition. The Europeans: sellers of civilization! A depraved people. And France, in particular, which had spread syphilis throughout the world.

“The fire! I remember it well!”, exclaimed someone in a low voice. Was it truly the Lord’s revenge because “Thus saith the Lord: my wrath shall be poured out upon this place, and shall not be quenched?”

Seventy-two victims. Someone loudly exclaimed: “Richmond the great is fallen, is fallen, and is become the habitation of devils, and the hold of every foul spirit, and a cage of every unclean and hateful bird”. Apocalypse 18: 2. And the death of Mrs. Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins Poe, the actress? Miserable innuendo. What happened was meant to happen. For what sins? Purifying fire, someone said with the faintest voice. Peace be on their souls. Seventy-two souls.

The theater, built a year before on the north side of H Street, suddenly became an incandescent trap when the chandelier, illuminated by lit candles, was raised toward the ceiling and brushed against one of the hanging scenes which immediately caught fire. A multitude of sparks began to rain down on the structure built to accommodate up to six hundred people. It was then that Mr Robertson, the editor, suddenly shouted: “The house is on fire”. It all happened at the start of a performance of the play Raymond and Agnes; Or, The Bleeding Nun which followed the comedy The Father, or Family Feuds. The news was well reported, with a detailed account of the events, by the Richmond Enquirer whose editor was present.

A blazing trap? An Apocalypse then? “Richmond the great is fallen, is fallen”, shouted some puritan. A miserable innuendo attributed the disaster to the behavior of Mrs. Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins Poe, the actress, recently deceased. From that moment only screams: “Save me, save me!” among the grim sound of bells and the sizzling of burning wood. The fire was devouring the whole place. Then the nauseating stench of bodies burning amid deafening screams: 54 women and 18 men died in the flames. Cruel fire. Many of the victims belonged to Virginia’s most illustrious families, including the Governor Mr George William Smith and the former Senator Mr Abraham B. Venanzoni. There were even several Negroes among the victims but few knew or wished to remember their names. It was true, however, that Gilbert Hunt, a black slave whose blacksmith shop was next to the theater, saved at least a dozen people. For some the deaths symbolized a supreme purifying act. Giving meaning to rigor, to moral intransigency and to the fundamentalism of rank. The fire gave inspiration and occasion for the rousing preaching of Evangelists, Baptists and Methodists against the monstrosities of a dreadful modernism, such as the immoral obscenity of theatrical shows and similar pastimes. Thus each catastrophe became the sign of a divine punishment for transgressive perversions. Mrs Elizabeth Arnold Hopkins Poe, the actress who had conceived a daughter out of wedlock? Someone then spoke of the Black Death and then tried to transform the entire event by talking about a red death.

Another round of sherry. More than one indeed to forget hideous events, when someone, Dr Snodgrass or Mr Rufus Wilmot Griswold? recalled that the terror for that purifying blaze resembled the memory of a tale. Edgar’s spirit seemed to be present at that obscene feast among glasses refilled with slow movements and obscure wills to forget whatever could be forgotten. Edgar, in fact, and a sad masquerade to give breath to the carnival legitimacy of a night. It happened in 1842: “The Masque of the Red Death”, someone murmured. Or was it The Masque of the Black Death?

“Alcohol purifies!”, exclaimed someone who was becoming inebriated with mediocre wine and who had joined the table of the three. “I know everything there is to know about alcohol”, he added, “I also know how to enjoy the shameless whirlwind of drinking myself senseless, even while aware of having to endure a beastly divine punishment. Because suffering a penitential punishment is inevitable if a community becomes infected with insolent strangers, people who are different, men of a different skin color, which is why there’s nothing left but to shamelessly inebriate ourselves”. Black death or red death: it doesn’t matter. It’s just death. Edgar would have smiled gladly.

He spoke no more and walked away. Arriving at his table he started counting the glasses he had before him, because he always drank wine in various glasses, almost to keep score of how much he was drinking.

Hence a sower of death seemed to mark a turning point when a community became debased by its inane and inhumane humanity. Difference was difference like the Red Death. Revenge and death then! Killing whomever attempted to subvert an order. In fact, Deuteronomy 7: 16 stated: “And thou shalt consumeall the people which the Lord thy God shall deliver thee; thine eye shall have no pity upon them: neither shalt thou serve their gods; for that will be a snare unto thee”. Thus “healthy and wise” friends were called together and they retreated into a healthy isolation. In this way it was possible to defy the contagion, that intruder who was about to appropriate their land, their culture. Outside the Black Death had been isolated. Thus entrenched in their new community, they imagined they could live without fear of contamination while outside there was only a devastated area tainted by men of a different skin color.

“Then there was the story of the slave-trading brigantine Creole that further increased

the discomfort and fear of the unfamiliar”, said that man as soon as he had downed a few glasses of vinegary wine. He came to join the three men once again. “You remember, don’t you?”, he asked stuttering. “Facts that prompted a reconfirmation of the faith in their ethical integrity by those who had the craving to rebel, with principled wisdom, against obscenity and immorality, considering despicable and perilous the reckless obsessions and woeful whimsy of granting freedom to slaves without properly protecting the rights acquired by the slavers.”

The Creole indeed, and it was 1841. A slave-trading brigantine transporting 135 slaves along the east coast, from Hampton Roads, Virginia, to New Orleans, Louisiana, where the market was more prosperous and one could obtain a better price for the sale of a Negro. It happened on November 7. It was evening. A band of nineteen slaves led by Madison Washington rebelled and took over the ship. A mutiny with no hesitation or qualms. Only a few wounded. However, John Hewell, a slave-trader, was murdered and one slave died from severe wounds. And the ship was turned toward Nassau, on the island of New Providence in the British Bahamas, a land of freedom since slavery had been abolished in the British colonies. In the American States it was declared that ill wills wished to question the sacredness of slavery.

Who was recounting this story in Richmond’s Old Swan Tavern? Nobody uttered adequate words, for or against. Everyone chose to remain in silence waiting for the man who had spoken about the Creole to retrace his steps and take his place among his glasses of sour wine. However, one by one, each person began to reflect on what that man had said. Pondering without talking to each other. Reconsidering what was ambiguous in that tale Mr Poe told in The Masque of the Red Death. Purifying fire and slavers’ will? Events, entirely fortuitous, that seemed to intertwine with the premises of a tale. The Masque of the Red Death!

What could come from thoughts wounded by scrupulous people and thrown onto the table of the imagination? There were many considerations in comparing events and lavish words of a tale born under the indelible sign of blood, of death as atonement. Hence the deaths in the fire in the Baltimore theater, hence the shameful and deadly offense against the white crew aboard the Creole which had suffered brutal violence without any respect for the canons of a judicious and moderate civilization.

Thus the conscience of innocence was destroyed by two life episodes that marked the shocking manifestation of a sort of subversive immorality. Contamination by nefarious dishonesty and wearing licentiousness for which it was necessary, in order to restore legitimate morality, to exile oneself from the community and wait for salvation through redemption. Protecting oneself through isolation to prevent further contamination while having to lose, ab initio