24,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Empire, Colony, Postcolony provides a clear exposition of the historical, political and ideological dimensions of colonialism, imperialism, and postcolonialism, with clear explanations of these categories, which relate their histories to contemporary political issues. The book analyzes major concepts and explains the meaning of key terms.

- The first book to introduce the main historical and cultural parameters of the different categories of empire, colony, postcolony, nation, and globalization and the ways in which they are analyzed today

- Explains in clear and accessible language the historical and theoretical origins of postcolonial theory as well as providing a postcolonial perspective on the formations of the contemporary world

- Written by an acknowledged expert on postcolonialism

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 366

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title page

Acknowledgments

1 Introduction

I

II

2 Empire

Empire and Civilization

The Geography of Empire: Land vs. Global Maritime Empires

The Governance of Empire

Two Models of Empire

Empires and Diversity

3 Colony

The Temporality of Colonization

The Colony as Settlement

Colonization, Migration, and Indigenous Peoples

Colonizer and Colonized: Intimate Enemies

The Colony as Trading Factory

The Colony as the Laboratory of Modernity

4 Slavery and Race

Slavery

Race

5 Colonialism and Imperialism

Colonialism

Imperialism

Imperialism without Colonies

6 Nation

The Nation as the Product of Colonial Expansion

The Nation and Human Rights

The Nation, Human Rights, and Slavery

7 Nationalism

8 Anticolonialism

Anticolonialism

Anticolonial Nationalism: Italy and Ireland

The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917

Strategies of Resistance: Rebellion or Reform

Culture as Soft Power

On National Culture

9 Decolonization

Phase One: 1776–1826

Phase Two: 1826–1945

Phase Three: 1945–Present

10 Neo-colonialism, Globalization, Planetarity

Neo-colonialism

Globalization: Free Trade and Advanced Technology

Resistance to Globalization

Planetarity

11 Postcolony

The Postcolony as Former Colony

The Settler Postcolony

The Postcolony as a Zone of Dysfunction

12 Postcolonialism

Knowledge and Theory

Orientalism

Culture

Language and Translation

Race, Ethnicity, Identity

Subalternity

Indigeneity

Nomadism

Migration

References

Name Index

Subject Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

v

viii

ix

x

xi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

Empire, Colony, Postcolony

Robert J. C. Young

This edition first published 2015© 2015 Robert J. C. Young

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UKThe Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Robert J. C. Young to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Young, Robert, 1950– Empire, colony, postcolony / Robert J. C. Young. pages cm Summary: “The first book to introduce the main historical and cultural parameters of the different categories of empire, colony, and postcolony, and the ways in which they are analysed today”– Provided by publisher. Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4051-9340-5 (hardback) – ISBN 978-1-4051-9355-9 (paper) 1. Colonies. 2. Imperialism. 3. Post-colonialism. I. Title. JV105.Y68 2015 325′.3–dc23

2015004134

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

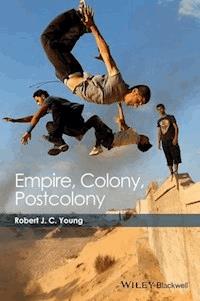

Cover image: Palestinian youths practising parkour, southern Gaza strip. © Mohammed Salem / Reuters / Corbis

For Ann

dearest companion and friendthrough generations

Acknowledgments

I would like to begin by thanking Emma Bennett, for suggesting to me that I should write a short book that would develop some of the conceptual and historical categories first presented in my Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction (Wiley-Blackwell 2001). The present volume is intended to complement, develop, and update that earlier account in a different form; the reader who is interested in more specific and detailed histories of the anticolonial movements in the Soviet Union, South America, Africa, and Asia will find extended analyses of them there. In general, given the intended length of this book, and against the academic’s natural impulse to give a long list of relevant sources, I have tried to keep references to a reasonable minimum. Although this book is designed to be read as a book, that is, in sequence, the individual chapters have also been designed to be relatively free standing; this necessarily requires occasional small repetitions.

At Wiley-Blackwell I would also like to thank Bridget Jennings and Ben Thatcher, and especially my former editor, the ever genial Andrew McNeillie.

I have been very fortunate in having a number of expert readers for the manuscript of this book at various stages. Stephen Howe read a late version with his customary attention to detail and dazzling encyclopedic historical knowledge, offering a host of useful suggestions and corrections. Douglas Kerr responded with characteristic elegance that made me consider unthought possibilities, rethink some knotty problems, and attend to my grammar; Hélène Quiniou read the manuscript with a Francophone philosophical brilliance that opened up a range of new possibilities, some of which must be held over for the future. Rita Kothari grappled with an early draft and asked some simple but characteristically penetrating questions about it; Mélanie Heydari read through a late version and pointed me towards many detailed improvements. I am sincerely grateful to them all and hope they feel that the final version is worth their very generous efforts. Virginia Smithson of the British Museum kindly located the Asante Ewer for me. I owe special thanks to Omar Mahdawi for walking me through Shatila Camp in West Beirut.

I would like to express my gratitude to New York University for supporting my research; Christopher Cannon for being such a considerate head of department; my colleagues on the Postcolonial Studies Project at NYU Toral Gajarawala and Jini Kim Watson; and also for collegiate discussions of all kinds, my colleagues John Archer, Tom Augst, Jennifer Baker, Una Chaudhuri, Patricia Crain, Patrick Deer, Carolyn Dinshaw, Juliet Fleming, Elaine Freedgood, Ernest Gilman, Lisa Gitelman, John Guillory, Richard Halpern, Phillip Harper, Josephine Hendin, David Hoover, Julia Jarcho, Wendy Lee, Larry Lockridge, John Maynard, Paula McDowell, Elizabeth McHenry, Maureen Mclane, Perry Meisel, Haruko Momma, Peter Nichols, Crystal A. Parikh, Mary Poovey, Sonya Posmentier, Catherine Robson, Martha Rust, Sukhdev Sandhu, Lytle Shaw, Jeff Spear, Gabrielle Star, Gregory Vargo, and John Waters. An especially big thank you to our administrators Lissette Florez, Susan McKeon, Taeesha Muhammad, Patricia Okoh-Esene, and Shanna Williams. My assistant, Hannah May Jocelyn, has helped to put me and my house in order, for which I remain very grateful. In Comparative Literature and elsewhere at NYU, many thanks too to Arjun Appadurai, Emily Apter, Lauren Benton, J. Michael Dash, Ana Maria Dopico, Allen Feldman, Dick Foley, Jay Garcia, Gayatri Gopinath, Hala Halim, Ben Kafka, Jacques Lezra, David Ludden, Nicholas Mirzoeff, Mary Louise Pratt, Arvind Rajagopal, Mark Sanders, Ella Shohat, Richard Sieburth, Robert Stam, Kate Stimpson, Jack Tchen, and Jane Tylus, and in New York more generally, Meena Alexander, Kate Ballen, Akeel Bilgrami, Tanya Fernando, Simon Gikandi, Kyoo Lee, Arwa Mahdawi, Rosalind Morris, Nick Nesbitt, Bruce Robbins, Mariam Said, Gayatri Spivak, Megan Vaughan, Tony Vidler, and Michael Wood. My thanks also to my students and graduate students over the past few years, particularly Shifa Ali, Durba Basu, Suzy Cater, Keren Dotan, Mosarrap Khan, Laurie Lambert, Jo Livingstone, Nick Matlin, Rajiv Menon, Omar Miranda, Joe Napolitano, Adam Spanos, Alice Speri, David Sugarman, and Shirley Lau Wong. At NYU Abu Dhabi I have been fortunate to have many productive conversations with colleagues, particularly Awam Ampka, Alide Cagidemetrio, Walter Feldman, Ama Francis, Wail Hassan, Stephanie Hilger, Paulo Horta, Dale Hudson, Philip Kennedy, Masha Kirasirova, Martin Klimke, Sheetal Majithia, Judy Miller, Cyrus Patell, Maurice Pomerantz, Gunja Sengupta, Werner Sollors, Bryan Waterman, Katherine Williams, Shamoon Zamir; many thanks too to Hilary Ballon, Al Bloom, and Fabio Piano, for making it all possible.

I have learnt much from colleagues and contributors while editing Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, particularly my fellow editors Neelam Srivastava and Teju Olaniyan, Sahar Sobhi Abdel-Hakim, and Stuti Khanna, as well as my patient assistants over the years Adrienne Ghaly, Weishun Lu, Kerrie Yang, and Heather Zuber. Many thanks too to our production editor Ben Wilcox, and Adam Burbage, our Managing Editor at T&F. I owe special thanks to Jack Messenger, our excellent, ever watchful copyeditor over many years, and also for this book.

My former colleagues at Wadham College, Oxford, have continued to provide inspiration and sustenance. I am always grateful to the College, and in particular to Terry Eagleton, Robin Fiddian, John Gurney, Stephen Heyworth, Christina Howells, Colin Mayer, Ankhi Mukherjee, Bernard O’Donoghue, Reza Sheikholeslami, and Oren Sussman, and elsewhere at Oxford, Elleke Boehmer, David Bradshaw, Maria Donapetry, Vincent Gillespie, Dhana Hughes, Sue Jones, David Keen, Hermione Lee, Laura Marcus, Peter McDonald, Heather O’Donoghue, William Outhwaite, Sowon Park, and the late Jon Stallworthy.

In talks and travel in many countries, including my own, I have been lucky to enjoy extended, hospitable conversations with many friends and colleagues over the years, particularly Marian Aguiar, Mai Al Nakib, Corina Angel, Isobel and Michael Armstrong, Derek Attridge, Deepika Bahri, Etienne Balibar, Emilienne Baneth-Nouailhetas, Cristina Baptista, Geoffrey Bennington, Omar Berrada, Homi K. Bhabha, Rosa Braidotti, Nadia Butt, Dipesh Chakravorty, Amit and Rosinka Chaudhuri, Caterina Colomba, Leyla Dakhli, David Damrosch, Theo d’Haen, Arif Dirlik, Maria Renata Dolce, PrathimMaya Dora-Laskey, Tobias Döring, Maud Ellmann, Rita Felski, Farah Ghaderi, Luke Gibbons, Paul Gilroy, Lucy Graham, Sabry Hafez, Stephen Heath, Diana Hinds, Elaine Ho, Habib Imtiaz, Maher Jarrar, Claire Joubert, Tom Keenan, Jean Khalfa, Dirk Klopper, Abhijit Kothari, Fran Kral, David Lloyd, Chandani Lokuge, Cristina Lombardi-Diop, Paul Lowndes, Jo MacDonagh, Elissa Marder, Susan Matthews, Achille Mbembe, Matthew Meadows, Ana Mendes, Ranjini Mendis, Aamir Mufti, Susanne Mühleisen, Francis Mulrea, Parvati Nair, Esmail Nashif, Siri Nergaard, Lynda Ng, Sarah Nuttall, Annalisa Oboe, Sandra Ponzanesi, Chris Prentice, Ato Quayson, Ruvani Ranasinha, Jacqueline Rose, Nicholas Royle, Sara Salih, Abdelahad Sebti, Rumina Sethi, Mark Stein, Stephanos Stephanides, Robert Stockhammer, Weimin Tang, Harish Trivedi, Vron Ware, John Wilkinson, Clair Wills, and Thanos Zartaloudis: I warmly thank them all.

My family, as always, has been my best resource: Ann, to whom this book is dedicated, Elizabeth, my companion through all my years, Amtul, who is ever hospitable and generous, my wonderful and always loving Maryam, Yasmine, and Isaac, and my dearest Badral.

A small amount of material in chapters 3 and 5 draws on my article “Colōnia and Imperium” in Barbara Cassin’s Dictionary of Untranslatables, trans. Emily Apter et al. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014). The citation from The Little Prince in the final chapter is also invoked in my article “What is the Postcolonial?,” Ariel 40: 1 (2009) 18–19.

1Introduction

Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.

(Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1852)

I

In an era of globalization, why should we care anymore about empires or colonies? Have not times moved on? Why should anyone be bothered with the history of fifty or more years ago when the world has changed so dramatically? Why carp on about the past when the Chinese and Indian economies are expanding exponentially and altering the economic and political landscape? Have not neoliberal economics totally transformed the global political scene? Surely progress and a desire for the new, not the presence of the past, are the constant state of things?

Or are things really so different? Has the history of the world had so little to do with the way that we live today? Are forced labor and slavery really just history? Do the many wars and civil wars of the twenty-first century, the civil strife and unrest, the ubiquitous presence of terrorism, exist only in the present, with no relation to the past? Do the problems of the West or of the global South have nothing to do with the very formation of the nations that are identified with those opposing terms? Have neoliberal economics merely perpetuated a new form of empire that has moved into a different phase?

There are many ways of understanding the world and the complexities of our present. One way is to examine how we are living out our lives in part as the product of our past. To fathom the many issues and conflicts that today seem to pose almost insurmountable problems – terrorism, fundamentalism, wars in Africa and the Middle East, insurgency in India, Sri Lanka, or Thailand – it helps to understand where those problems have come from and under what conditions they have emerged. Sometimes it can even help to guide our political judgments: with their knowledge of what had happened before, few historians would have advocated the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. As the Spanish philosopher George Santayana famously put it: “those who cannot remember the past, are condemned to repeat it.”

Some things continue in other forms. Colonialism and imperialism involved the subjection of one people by another, and developed in their modern varieties in conjunction with other kinds of domination: of women, of slaves, of minorities, of the poor, of relatively powerless sovereign peoples, of the resources of the earth. So long as oppressive power of that kind continues, then analysis of the forms and practices of colonialism and imperialism remains relevant to the problems that we face today.

II

Order something on the Internet and you soon come to the moment of entering your address. At this point you will often be presented with a drop-down box that contains a predefined list of the names of all countries, starting with Afghanistan and ending with Zimbabwe. The list is almost two hundred and fifty countries long. Suddenly, your country is put on an equal footing with all others: you may live in one of the western countries which took part in the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, but here Afghanistan sits proudly at the top of the list, and you will have to scroll down almost the whole way to the bottom to find the United Kingdom or the United States. We take it for granted that everyone lives in or comes from a particular country, and that the world is made up of diverse, separate nations that are all represented in the organization called the United Nations, which oversees the governance of the world.1

Open Bartholomew’s The Century Atlas of the World, published in London in 1902, and you will find a list of “Principal States with their Colonies and Protectorates.” The number of such states here amounts to only thirty-seven. What happened, then, between 1902 and today? Not only are there fewer countries – neither Afghanistan nor Zimbabwe are to be found – but the names are also different. Here the names are not listed alphabetically, as on the Internet drop-down box, but by the size of the territory that they designate:

British Empire

Russian Empire

Chinese Empire (including Korea)

France

United States (including Hawaii, Cuba, Porto Rico [

sic

], the Philippines, Guam, and Tutuila, &c)

Brazil

Argentine Republic

Ottoman Empire

German Empire

Congo Free State

Portugal

Netherlands

Mexico

Peru

Persia

Bolivia

Columbia

Venezuela

Morocco

Sweden and Norway

Chili [

sic

]

Italy

Siam

Austria-Hungary

Abyssinia

Spain

Central America (5 states)

Japan

Ecuador

Denmark

Paraguay

Rumania

Bulgaria and E. Rumella (included in Ottoman Empire)

Greece

Servia [

sic

]

Switzerland

Belgium

It’s an interesting list. Several countries that existed at that time, such as Liberia, are not even mentioned. Apart from the ranking by territorial size, what distinguishes it from a modern list is that some states are described as empires (if so, it now seems strange that France, Austria-Hungary, or Japan were not described as empires at that time). Portugal and Spain were no longer considered empires, though they had been empires and still had colonies; Denmark and Belgium if not empires certainly had colonies. Technically, the Congo Free State at that time was an independent fiefdom of the Belgian King: it would be assimilated into the Belgian Empire as a colony in 1908 after the scandalous conditions there were exposed. Morocco, whose coastal territories were already (and still are, under a different name) a Spanish “protectorate,” would be divided up by France and Spain two years later in 1904.

Many of the countries on the list had been part of other empires over the previous one hundred and fifty years: Belgium itself, Italy, Greece, Serbia, Romania, the United States, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, Columbia, Venezuela, Chile, Central America, Ecuador, Paraguay. Even Switzerland had been occupied by the French between 1798 and 1815. In fact very few of the countries had not been colonies of some kind in modern times: some that were themselves empires – Britain, China, France, Russia, Turkey – plus Abyssinia, Japan, Persia, Siam. Abyssinia was then invaded and occupied by Italy in 1936; Persia (Iran) was occupied by the British and Russians in 1941; Japan was occupied by the United States in 1945. Thailand was the only country that managed to avoid colonization, even by the Japanese, though like China and Japan itself in the nineteenth century, it was obliged to grant extraterritorial “concessions” and is often described in the period as a “semi-colony.” Though repeated attempts have been made to conquer Afghanistan since the nineteenth century, it has never been successfully colonized, apart from brief periods in which the colonizers rarely if ever controlled the whole country; in earlier times, it did, however, form part of the Persian Achaemenid, Sassanid, and Safavid empires. China which was already conceding territories to the imperial powers in the nineteenth century (by World War I, ten of the world’s most powerful countries had concessions in China) was then invaded and partially colonized by the Japanese in the twentieth century. France was occupied by Germany; Russia underwent a convulsive revolution which prompted the international twelve-nation alliance invasion of 1917, followed by the German invasion of 1941, defeated at the cost of millions of lives. Turkey, which the Allied powers tried to dismember almost entirely in 1923, managed to hold them off enough to create its modern boundaries. During the period from 1750 to 2000 only Britain, Russia, Thailand, and Turkey have remained autonomous states throughout, albeit in changing geographical and political configurations. This autonomy has not preserved them from invasion, sequestration of their territory, internal revolution, or separatist campaigns. All these countries face movements demanding independence or political autonomy – from Scotland, Chechnya, the Malay Pattani, and Kurdistan.

We perhaps think of the world as it is as permanent, but it is chastening to reflect that in the last two hundred and fifty years, scarcely more than a breath in human history, its political stability has been minimal. Go back a few more hundred years, and the story hardly becomes more encouraging. State formations, whether as empires, nations, or unions, come and go, across the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. From a longer perspective, the history of the world amounts to the formation and reformation of empires, appearing, expanding, and contracting like biological forms constantly emerging, growing, usurping, transforming, overpowering, retreating, disintegrating.

Historically most empires gave way to further empires. The end of the European empires, by contrast, produced a new global political formation that distinguishes them from all empires that preceded them: the world of nation-states. It was in that environment that the postcolonial emerged as a specific way of addressing the inequities and injustices of both imperial rule and its global aftermath. As V. S. Naipaul put it in 1967: “The empires of our times were short-lived, but they have altered the world forever; their passing away is their least significant feature” (Naipaul 1967: 38).

Note

1

Yet at the United Nations only 192 countries are represented. Where do the additional fifty or so names in our address list come from? Some of them are uninhabited, such as Bouvet Island, in the Antarctic, a colony of Norway. Others have names such as “Palestinian Territories, Occupied,” “United States Minor Outlying Islands,” “Netherland Antilles,” or “British Virgin Islands.” None of these addresses or destinations is a sovereign country.

2Empire

“My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings: Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!” Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare, The lone and level sands stretch far away.

(Percy Bysshe Shelley, “Ozymandias,” 1818)

Considered from a historical perspective, what is most extraordinary about empires is the constant metamorphosis intrinsic to their very existence, their rise and fall, formation, reformation, and deformation. Every empire changed the culture of the territory under its rule, but that transformation would in turn give way to another. Despite their grandiosity, power, and claims of endurance, empires have historically been unstable, their boundaries constantly altering through the course of their existence like the protean shifting outlines of living amoeba. Empires in fact can only be charted properly with varying or animated maps – in general they were modified so frequently that any map can only be a snapshot of an empire’s extent at any particular moment. Against this constant transformation of boundaries, and pattern of rise, fall, and extinction, the reiterated ideology of empires has been one of stability and endurance, a paradox highlighted with reverberating irony in Shelley’s famous poem “Ozymandias” about the Egyptian pharaoh better known as Ramesses II. At the end of the poem, Shelley cites the grand imperial claim made in the statue’s inscription on its base, but centuries later its wrecked state, its location in the middle of the empty desert, works to ironize and completely reverse its original intended meaning.

As any empire expanded, so did the extent of its boundaries: on the one hand this only prompted the desire for further conquests, while on the other hand it made those peripheries harder and harder to defend, more open to attack. Every new conquest or annexation produces more borders to secure, and further limits against which to push and which territory to conquer. At any sign of weakness, those already conquered might take their chance to rebel. Meanwhile, far distant frontiers become less and less determinate the further away they are, and imperial authority grows ever more tenuous at those points. This principle forms the inherent vulnerability of all empires, and one reason why most of them remained unstable and eventually collapsed. Empires have almost always been destroyed by competition for power from without or from within. The story of empire is consistently one of expansion, usurpation, contraction, and dissolution.

Many empires have been driven by ambition and the aspiration for empire of individual conquerors like Ozymandias (Ramesses II c.1303–1213 BCE)—such as Cyrus the Great (576–530 BCE)—Alexander (356–323 BCE)—Julius Caesar (100–44 BCE)—Timur (Tamerlane) (1336–1405)—Genghis Khan (1162–1227)—Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821), and Hitler (1889–1945), or developed by a series of such figures, as in the case of the Ottoman Empire (Murad II, Mehmed II, Selim I, Suleiman the Magnificent). Some empires, such as the British, expanded, contracted, expanded, and contracted again more episodically without being driven by a particular sovereign ruler (in the nineteenth century the historian John Seeley famously claimed that the British Empire had been acquired in a “fit of absence of mind”) (Seeley 1971: 33). Nevertheless the motivations for empire, whether of sovereign, trader, or explorer, have usually been similar: glory, power, and money. As Jane Burbank and Frederick Cooper put it in their Empires in World History: “The men who sailed forth from Western Europe across the seas in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries did not set out to create ‘merchant empires’ or ‘western colonialism.’ They sought wealth outside the confines of a continent where large-scale ambitions were constrained by tensions between lords and monarchs, religious conflicts, and the Ottomans’ lock on the Eastern Mediterranean” (Burbank and Cooper 2010: 149). These explorers were the entrepreneurs of their time, trying to bypass the constrictions of class and rank in their own societies. Most empires have been driven by the desire for wealth extracted from somewhere else: Julius Caesar invaded Britain for the same reason the Spanish invaded the Americas: gold. The other motivation has been religion: whether for religious freedom (the Pilgrim Fathers), or more often for religious proselytization. In allocating the division of the Americas between the Spanish and the Portuguese, the Pope, as God’s representative on earth, had justified their colonization on the grounds of the promise of the conversion of the indigenous peoples to Christianity, in an era when Catholic missionaries such as Francis Xavier were also moving into Africa and the East. The Islamic Caliphate expanded from Saudi Arabia from the time of the Prophet Mohammed; in accordance with the Constitution of Medina, religious tolerance for “the people of the book” (Jews, Christians) was the normative rule, even if in practice it was not always observed, particularly with respect to Sunni–Shi’a relations, and there were certainly missions that produced, or enforced, large-scale conversions.

Many European empires were also created in part through the drive for emigration and settlement producing settler colonies on the original Greek model, in order to get rid of surplus, unemployed and unproductive populations: the Spanish in the Americas, the Dutch in South Africa, the English in North America and Australasia, the Italians in Libya – just as today the hungry, the unemployed, or the underpaid of the world migrate in search of a better life. The settlement colonies where such people landed, far from the metropolitan center, have always been prone to detach themselves from the empire, particularly if they were an ocean or two away.

However diverse their political formation, all empires have been geographically extensive: for an empire to be worthy of its name, its boundaries must be far-reaching. To call your territory an empire when it is the size of a city, state, or a province merely suggests unrealistic aspiration – no one quite seems to know why New York calls itself “the Empire State.”1 Traditionally, empires were political formations that were developed over time from particular geographical areas or through nomadic occupation. For the most part, they grew by conquest, though sometimes by dynastic marriage. Most empires have existed simultaneously with others, along with local kingdoms, states, or nomadic tribal groups that lived outside any imperial umbrella. To the extent that empires trace extensive and sometimes enduring political formations, they offer ways of constructing large-scale historical narratives on a global scale. Today, globalization has meant that historians often present world history as the history of its empires. That is one way of organizing it, a return in fact to the perspective of the eighteenth century when Enlightenment historians such as Gibbon or Volnay were preoccupied with the decline and fall of empires. During the nineteenth century’s age of imperialism, with its attendant racial and cultural hierarchies, attention switched to a focus on civilizations. In the twentieth century, traditional history in western countries preferred to employ the narrative of the expansion of Europe, beginning with the history of “Ancient” civilizations by which was meant Greece and Rome, moving on to the development of European culture during the Renaissance, the flowering of modernity with the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century, the expansion of Europe and the formation of European empires, followed by the world wars, the Cold War, decolonization, and the advent of a world of nation-states. All this could be presented implicitly or explicitly as part of a larger narrative, of the progress of (western) “civilization,” often identified with “modernity,” as such.

Empire and Civilization

What is the difference between an empire and a civilization? Very little in practice, for many are identified as both. Some “civilizations” of course did not aspire to the status of empire, but they probably did not call themselves a “civilization” either. That is what we call them now because we classify them as societies that produced their own distinct forms of settlement, agriculture, technology, trade, writing, religion, and art, all things that are also often characteristics of empires. The choice of term depends more on whether you wish to foreground the cultural or the political category. We speak of the early Indus Valley Harappan civilization only because it is so early that we have little detailed information about its political organization – even its duration is a matter of debate. As a cultural category, though civilization has always been in the eye of the beholder, it has usually been identified with the development of cities and their urban culture (the word itself derives from civis, citizen). Civilization has typically been opposed to foreign societies regarded as uncivilized, “barbarian,” “savage,” or “primitive.” Many empires have claimed to be bringing civilization to the territories that they appropriated. One of the major justifications of empire in the nineteenth century was that westerners were fully civilized while non-westerners existed in varying states of non-civilization – imperialism therefore was claimed to bring “civilization” to them, an ideology most acutely formulated by the French in their concept of the mission civilisatrice, founded on their assumption that there was (or is) a civilisation française. Civilization in this instance functioned as a secular version, appropriate for a Republican state, of a much older justification of empire and colonization: Christian conversion. It was only the Spanish and the Portuguese who had been formally obliged to justify colonization and empire through missionary work, but all colonies were subjected to missionary endeavors, and missionaries utilized any available colonial outposts to facilitate their efforts, even at times urging further colonization on their behalf. Though in practice their relation with colonial administrators was often somewhat conflictual, the link between missionary work and colonization was a means of giving the practice of empire an aura of moral purpose. Civilization and missionary work on behalf of civilization’s religion, Christianity, became almost identical in the mind of many imperialists, with both being regarded as a self-explanatory good, much like overseas “aid” and “development” in more recent times.

This imperial history has made the whole idea of “civilization” difficult to employ today, since the very concept is widely recognized to involve many ethnocentric cultural assumptions. As a result, historians now prefer to use the term “empire,” which suggests a more comparative, historical, less judgmental perspective. If the two are often still identified, it remains the case that some empires have produced more “civilization,” in the sense of more distinctive and enduring cultures, than others. Those that lasted longest, such as that of Egypt, had the best chance of creating a civilization of their own. Egypt, unusually, was comparatively uninterested in spreading its own culture abroad; most empires, by contrast, have tried to impose some mark of the imperial realm on the territories that fell under imperial sway: a common sovereign, followed by a common language, script, law, coinage, architectural style, and, sometimes, religion. In this respect, the first major “empires” were generally also distinct civilizations – Egypt, Assyria, Babylon. At its greatest extent, in the fifteenth century BCE, the boundaries of the Egyptian Empire extended as far as modern Turkey in the North, and Eritrea in the South, but despite its size it was only one of the great powers of its day, coexisting in the territory of what is now called the Middle East with many rival empires, such as the Babylonian and Assyrian. Subsequent empires in Asia included the Achaemenid or Persian Empire under Cyrus the Great, the Macedonian Empire under Alexander the Great (which stretched to the Himalayas), and the various dynastic Chinese empires whose geographical borders habitually shifted. Empires on the Indian subcontinent changed many times between the time of Alexander and the arrival of the Mughals. The history of the Indian subcontinent has been the constant creation, dissolution, and reconfiguration of multiple empires, of varying geographical extent, the largest of which included the Mauryan Empire under Ashoka the Great, the British Indian Empire, the Buddhist Pala Empire, the Muslim Mughal Empire, and the Hindu Gupta Empire. Other major empires elsewhere before the modern period would include empires outside the Eurasian landmass such as those in Mali, and in Central (Aztec) and South (Inca) America, and, back on the Eurasian landmass, the Greek and the Roman, the second Persian Empire, followed by the religious empires of the Byzantine and Holy Roman Empires and the Abbasid Caliphate. By the seventeenth century the Ottoman Empire stretched from the Persian Gulf to Algiers to the borders of Vienna. The largest empire in terms of contiguous landmass in any period, however, was the Mongol Empire of the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries founded by Genghis Khan, which extended from the Pacific to Europe and is supposed to have included 30 percent of the world’s population within its no doubt somewhat tenuous boundaries.

The Geography of Empire: Land vs. Global Maritime Empires

Despite their differences, all these empires had one thing in common that enabled the transmission of their particular cultures or civilizations: they were made up of contiguous territories on a single landmass. The Islamic caliphates, for example, spread out wherever the undemanding dromedary camel could take the conquerors (Silverstein 2010: 6). Alexander the Great extended the eastern boundary of the Greek Empire into India, while founding the city of Alexandria in Egypt. Expansion over adjoining territory was also the basis of some modern empires, such as Napoleonic France, Nazi Germany, and the Russian (Soviet) Empire, all of which operated in the more traditional form of landmass expansionist empires. Russia, proclaimed an empire by Peter the Great in 1721, has consistently incorporated, or reincorporated, adjacent territories from the original Kievan Rus’. By 1866 it had moved overseas, or rather over ice, reaching from North America (with settlements in Alaska and California) to the Baring Sea, from the Arctic to the Baltic. Having given up much of its imperial territory during World War I, then regaining it after World War II, and then losing it again with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, by 2014 Russia had resumed its expansionist mode, annexing the Crimea and fermenting separatism in Eastern and Southern Ukraine – a development impressively forecast in 2001 by the political scientist and analyst of the structure and dynamics of empires, Alexander J. Motyl (Motyl 2001).

The United States in some sense operated as a mirror image of Russia. While Russia expanded ever eastwards, as soon as they achieved independence in 1776, American colonists started expanding westwards from the original thirteen colonies on the Eastern seaboard of North America into territory hitherto explicitly designated by the British as Native American reserves; in 1803 the United States contracted for the Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon and bought the remaining French territories in North America. An imperial policy was followed more deliberately under President Polk when the United States annexed Texas in 1845, leading to the Mexican–American War which in turn led to the incorporation of Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah. Having reached the western limit of the Pacific Ocean, from 1845 the United States began to acquire territories beyond its own immediate landmass, starting with a concession in China negotiated in the Treaty of Wang Hiya. Alaska was purchased from Russia in 1867. More controversially, Hawaii was incorporated in 1898 after Queen Liliʻuokalani had been overthrown in 1893 (Hawaii remains the only US state whose flag contains the British Union Jack). At that point, the United States began to take the form of a maritime empire, absorbing overseas territories taken by military force. Yet the difficulties soon became apparent: only two of these, Alaska and the islands of Hawaii, have been made into a state of the union. Other territories, many of which were annexed at the time of the Spanish American War (1898) – Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, American Samoa, Northern Mariana islands, the Marshall islands – were either subsequently granted independence, became independent, or remain suspended in the curious status of “unincorporated territory.” In 1913, with a change of president, the United States’ sixty-year period of seeking to be a global empire in the Pacific was changed dramatically in favor of national self-determination for all colonies around the world. Empire and democracy have coexisted uneasily as US national policy ever since.

Before achieving independence, the United States itself had been a part of a very different kind of empire that was not formed on a single landmass but stretched around the world: the global maritime empire of Britain (Darwin 2013). This was the other form of empire, involving the occupation of landmass on far-away continents (Howe 2002). Such empires are best understood as global maritime empires, operating as transoceanic economies based on trading posts networked around the world and an aggregate of geographically dispersed colonies, all held together by the new technology of ocean-going ships and, later, undersea telegraph cables.

For the most part, earlier empires consisted of proximate territories across a single landmass. From the eighth to the eleventh centuries, however, the Vikings traveled extensively, in their extraordinary long ships which used an advanced technology that enabled them to sail against the wind as far as North America, Russia, and the Eastern Mediterranean, not only raiding as is well known from popular mythology, but also founding colonies in present day Newfoundland, Labrador, Greenland, Iceland, and even Southern Italy. While Vikings set up colonies, they were never agglomerated into a connected empire, in part because there was no stable state in the modern sense at home to be its center. By the early sixteenth century, Europeans were building ocean-going “caravels” that used navigational aids such as the astrolabe, compass, and cross-staff (technology in part derived from maritime Asia) that enabled sailors to return across the oceans. As a result, it became possible to form empires that were not geographically proximate. Unlike the Vikings, these later colonists were able to keep in touch with their homelands relatively easily, however distant they may have been.

This one factor distinguished modern European empires from all others that had preceded them. Combined with the development of other forms of military and communications technology, such as firearms and cannon (first used in China) (Goody 2012: 274), or later the machine gun and the telegraph, European states were able to control territories all over the world to which they had no geographical proximity. In this vast imperial web whose fundamental organizing principle was the flow of trade, three different kinds of colony can be distinguished: the settler colony, the unsettled exploitation colony, and the fort or naval base, which we may call the garrison colony.2 In the modern era, the garrison colony has not comprised a city, as in Roman times, but a military base, such as the sovereign territories of Britain and the United States on the islands of Cyprus (Akrotiri and Dhekelia) and Cuba (Guantanamo), respectively, which are wholly military enclaves. The strangest case is Diego Garcia, which was sold to the United Kingdom by Mauritius while still a British colony in 1965; the British Labour government then forcibly resettled the Chagossian inhabitants in order to lease the island to the United States for use as a naval base; since 2001, it has operated as a site for extraordinary rendition.3 The island’s former residents continue to campaign for their return home, despite losing their last legal case against the British government in 2008.

While oceanic economies made up of trading networks such as those of the Indian Ocean or Southeast Asia certainly existed in the past, globally dispersed maritime empires were an exclusively European entity until the advent of the Japanese Empire at the end of the nineteenth century. International trade in luxury commodities had been going on since at least Greek and Roman times, but in the sixteenth century the