7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Errislannan, or Flannan's peninsula, juts out into the North Atlantic on Europe's western extremity south of Clifden, Connemara, Co. Galway. The home of Alannah Heather, it gave shape to her life, and to this book. The Heathers were minor Protestant gentry and estate-owners who occupied Errislannan Manor for five generations from the 1790s to the 1960s. The author tells their story, using family diaries and letters salvaged from a coach-house loft before the auction, and enlarges upon it in this remarkable self-portrait, articulating a childhood and landscape peopled by cottagers and fisherfolk, islanders and evangelicals, and a richly eccentric body of relatives. Their history reveals Ireland's in microcosm – touching upon the Great Famine and subsequent diaspora, the 1916 Rising and civil war, the Alcock and Brown landing on Derrygimlagh bog, and the more intimate dramas of unrequited love, bereavement and isolation, in a perpetual cycle of exile and repatriation. Aslant of an Anglo-Irish upbringing, Alannah Heather's career as an artist took her to the Slade and London in the 1920s, to St Ives on her marriage in the 1940s, and to Sark in the Channel Islands, with painterly excursions to Bruges and Budapest during the 1930s, returning time and again like a salmon to its beloved spawning-ground in Connemara. The voice in Errislannan is immediate, affectionate and unobtruding – the narrative, illuminated by shards of memory, restores a personal and collective past. It is a singular journey of self discovery, and an enduring masterwork, resonant as its subject's canvases.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1993

Ähnliche

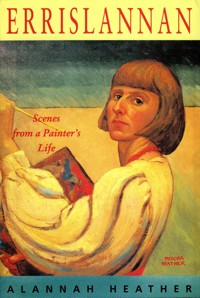

Errislannan

SCENES FROM A PAINTER’S LIFE

Alannah Heather

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

Contents

Title Page

1 The Fall of the Loft

2 Journeys to Dublin by Bianconi Car and Canal Boat

3 The Great Famine and Queen Victoria’s Visit

4 Achill Island and County Sligo

5 England, and the Road to Paradise

6 The Heather Family

7 The Manor Interior

8 Tinkers and Tenants

9 France, the Great War, and Back to Errislannan

10 The 1916 Easter Rebellion

11 Picnics

12 Alcock and Brown; Sundays at Home

13 The Galley, and the Lake

14 Johnie Dan, Val Conneely, Anne Gorham, and Mrs Molloy

15 Civil War, and Leavetaking

16 London, Bruges; a Grandmother’s Funeral, and Brother’s Death

17 The Journey Home

18 My Father’s Death, and Departure from Knockadoo

19 Sark and the Slade

20 The Gate Lodge, and the Road to Clifden

21 Return to Errislannan

22 The Races at Omey, and Crumpaugn Boathouse

23 The Charlotte Street Studio

24 Hungary

25 Autumn in Sark, and War

26 Cornwall and Marriage

27 St Ives, and a Homecoming

28 The Connemara Pony Show, Seaweed Harvest, and Dances

29 The Bishop and the Baptist

30 Post-War Sark, Roger and Connemara

31 Night Falls on Errislannan; Roger’s Death

32 Return to the Islands

Plates

Copyright

CHAPTER 1

The Fall of the Loft

‘There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth.’

Huckleberry Finn, Mark Twain

If one thing more than another made me write this book it was the fall of the loft over the coach-house in the stable yard. All the beams gave way at once and down came sacks of letters and diaries, trunks of clothing and linen, crates of honey, boxes of china and broken furniture. Regimental flags wrapped in old corsets, dozens of sermons, my great-grandmother’s will and a huge block of wood on which mutton had been chopped up. All this, draped in cobwebs, fell on the carriage (known as the coach), which took six inside and three on the box, the side-car and the trap. The sacks of letters and diaries were put in a dark wet outhouse in the yard. Ranging in date from 1790 to the 1960s, they give fascinating glimpses into the lives of the last five generations living in Errislannan, Burmount Manor (the previous family home in Co. Wexford) and the Dublin house. To read them one needs a magnifying glass, and they are so full of biblical quotations that they are tedious except for the unusual or tragic event.

Connemara, that land of mountains, lakes and bogland, stretches out into the Atlantic protected by many small islands. The high rocky fingers of land are divided by bays which wind far back nearly to the foot of the mountains. One of these fingers is the peninsula of Errislannan, which is almost an island, so close do the seas come at its neck. The Manor in the centre is beautifully situated, with the lawn – a hayfield in summer – running down to a small lake, Loch Nakilla. It is sheltered from the north by a horseshoe of trees which slopes down to the lake on each side of the house. Its stone plastered over, with three small dormer windows and one big one facing out across the lake to the distant line of sea and the beam of Slyne Head lighthouse, the house is half covered with ivy and takes its place among the trees.

Among the papers of the 1790s I found the sad story of my great-great-grandmother, Jane Wall (née Frayne), written on bits of paper sewn together to form a little diary. ‘I was married in Furlonge Cornmarket in the presence of … and was remarried in the Church of Castlebridge on 24th June 1790 in the presence of … ’, and here followed a list of officers and titled gentlemen and their ladies. Obviously the second wedding was a respectable one. ‘Sarah was born in October 1790, Richard Henry Wall’ – my great-grandfather, who bought Errislannan – ‘born 1793’. Then, ‘Parted with my dear mother to return to Dublin being near lying down of my Dear Little Daughter, and met a very unfriendly welcome from her father at my return, which Alas! was often the case with me.’ That baby, little Mary Jane, died when she was three ‘and was buried in Carnolway Graveyard in the County Kildare near the big thorn bush on the off side of the Church about a yard from the thorn, the side next to the Church’. Later ‘My Sarah and Richard were taken away from me by their father and left in the County Kildare. I parted with them beyond Ballareen Church … that day miserable! May the Lord protect them and grant me a happy sight of them in this world and in the world to come, Amen.’ Perhaps it was being taken away from his mother as a child which made my great-grandfather so difficult to live with and accounted for there being none of the usual expressions of regret when ‘Papa left us.’

There is a photograph of him – ‘The Rev. Richard Henry Wall D.D. and his wife and daughters’ – posing on the lawn at Errislannan among the haycocks; the women in crinolines, the men in top hats. My great-grandfather is sitting on the only chair, hand on stick. The women stand meekly round with smooth hair parted in the middle; beautiful gentle faces caught by the camera for future generations to see. Their brothers were far away; Henry, whose fascinating naughty diary I found, was killed in the Indian Mutiny; George was an army surgeon and was killed in India. James, in the navy, died, with all his shipmates, of yellow fever in Jamaica and was buried under a palm tree on the beach. Walter died unmarried though he was a great ‘ladies’ man’ and spent much time dressed in wrinkled stockings and knee-breeches at the Viceregal Lodge.

Of the girls in the photograph, Great-aunt Sarah was extremely musical, playing the harp and singing the famous Tom Moore’s Irish Melodies with Tom Moore playing her accompaniments to ‘Oft in the stilly night’ and ‘Believe me if all those endearing young charms’. She longed for Dublin and did escape to Paris, but made the mistake of letting her father know where she was. He wrote saying she was insane, and her defiant reply has survived the years: ‘Dear Papa, I am not insane but on the Seine.’ He forced her to return to Errislannan, where she literally pined away and died of misery. I found her harp in the attic of Drinagh covered in mould, with the strings lying on the ground like seaweed.

Then came Great-aunt Rachael, who was loved by everyone and was the mainstay of Errislannan. Then my grandmother, Henrietta.

The West of Ireland does not breed husbands. George Moore’s book about the maidens of the West of Ireland, A Drama in Muslin, gives a tragic picture. They were pretty, healthy girls, but all their brothers went to school in England and then into the British army or navy, and their sisters were left pining for young men. Mercifully when my grandmother was about to pine, a young clergyman called George Heather came along and asked her to marry him. On the wedding day in 1866 a full gale was blowing. The rain fell, the wind blew and howled around the church for this, the first wedding to be celebrated there since it was built in 1855, and the last for over a hundred years.

Henrietta kept her bridegroom waiting at the church for two hours as a bridesmaid’s dress had not come from Clifden. One can imagine the bridegroom’s cold feelings, both physical and mental, and the shivering of the guests until the bride was seen to enter the churchyard. Then the storm took over and her veil went sailing over the tower until another gust blew it down tangled in the gorse. The wedding guests had to retrieve it and were soaking wet before the laughing bride passed up the aisle.

Great-aunt Alice was a memorable character, though I only knew her when she was over eighty. She then had a mass of white curly hair, cut fairly short so that it stood out round her head like a halo, and magnificent bright blue eyes, under which she smeared in with her finger a large patch of black grease-paint. Alice would walk fifteen miles when she was eighty-two, dressed in a flowered kimono and an old felt hat, gone to a point with the rain, and carrying a long black stick with a silver knob – not for support, but to tap the road and poke at people and things. She was very deaf so did all the talking, and would make up witty limericks and rhymes about people as she approached them; then, flourishing the stick, she dramatically recited her piece, reducing the victim to silent hate. One farmer got the full treatment over a period of years: up came the stick and a deep voice intoned, ‘Who stole the pig?’ referring to an embarrassing episode of the past. A plain cousin staying with us got this at the dinner table:

M stands for Mabel,

Who sat at the table

And tried to eat more

Than she really was able.

With the lean kine of Egypt

She dared to compete

And vox populi thundered

Her success was complete.

From then on she and her sisters were always referred to as the ‘Kine’.

I remember my brother and me cowering behind walls when Great-aunt Alice passed, we were so afraid of her. Once I sat on a bag of eggs and she heard the crunch. Her black-ringed eyes appeared over the wall and we flew away over the hill, working ourselves up into nightmare fears, which were quite groundless.

She built two stone bathing-boxes on a high rock from where one could dive into the deep green sea. She considered our bathing-dresses indecent and herself wore a long gown of butcher-blue with slits for arms, tied only round the neck. She mounted the rock, put back her shining white head, raised her arms and took a spectacular leap into the air, sailing down with the gown acting as a parachute. It was then our turn to be embarrassed.

Great-aunt Alice’s diaries are much livelier than the others, even as a child in 1854: ‘We made Paddy get up early and catch our ponies for us. Very cross. We saw the sun rise over the mountains and saw it set, coming home from Ballyconneely, over the Atlantic.’

I have managed to trace some love affairs, but they were very one-sided as all the local men were married or about to have weddings, after which she always wrote RIP. ‘Walked home in the dark arm in arm. Ecstasy … delicious … exquisite … he talked to me for a long time.’ Or, ‘He did not speak to me. Miserable and agony of mind. Could not sleep for thinking of Capt. P. Went skating with Capt. P. and fell in. Very cold and wet. Nearly died.’ The next day ‘very ill’. But the following day, ‘Rode Capt. P’s horse into town and walked home.’

The next year, ‘Called on Mr C. and he would not notice me. Stayed late with Irelands, in Clifden, sea rough and nearly dark; tide too far out for boat.’ ‘Went by long car 40 miles to Westport and on by carriage to Cahille. Janie and the children well [Heathers]. Ben cruel to me. I don’t like him any more. Do not break the bruised reed.’

‘Wedding day of Francie Robinson to Dick Pelley. Cried a lot. Mr Paddon proposed to Kathleen. Mr Corry married to Sec. Awfully depressed.’ (‘Sec’ was the disparaging name always given to Mrs Corry, who had been a secretary.) ‘Capt. P. said I would be in a lunatic asylum yet.’ ‘Illuminations for Daniel O’Connell. Sec was there. He only said good-night to me and he is going to Dublin tomorrow. Tired to death.’

Then among the texts and biblical quotations, some blasphemous hand has written in a different ink, ‘Went to Errismore races and lost £5. I drowned my sorrows in eight pints of beer. Johnnie took me home and put me to bed.’

Great-aunt Alice finally married a clergyman much younger than herself: Charles Heaslop, who had come as a curate to Mr Corry, the Rector of Clifden, the earlier object of Alice’s love. Charles proposed and was refused, but Great-uncle Walter, who was hidden under the table, ran after him and brought him back. The superstition that it is unlucky to return to a house without sitting down was fully justified. He stood and found himself engaged, to rue many the day.

Alice and Charles had two very beautiful, saintly daughters, Phedora and Viola, but their mother put an end to all their love affairs. I found their love letters stuffed into a dressmaker’s dummy in the Drinagh attic – and they died spinsters. They are the only members of the family to be in the peerage, under the heading of Lord Byron, of all people. Phedora, who comes into this story later on, was born with difficulty at Letterfrack, a few miles from Errislannan; Great-aunt Rachael describes the dramatic event. Her father, the son of an Admiral Heaslop, had an intense love of the sea and removed himself from domestic disharmony in Errislannan by taking to a half-decked boat, with a cubby-hole in which he slept.

After Viola’s birth Charles left home for seven years, discarding his family. He became a chaplain in the navy, where he was tutor to King George and the Duke of Clarence as young boys. Charles is important to me only because he built a boat-house, which fifty years later I used as a studio and sometimes slept in. After leaving the navy he had twenty-seven parishes, driven on by his eccentric wife. When Great-aunt Alice thought she was about to die she returned to lay her bones with the family. She pounded on the piano with great vivacity until the day she died and was buried exactly as planned, in her beloved Errislannan. Perhaps her best memorial was the letter-box in the stone wall near the lodge. She disliked government green, so took any paint she had by her and produced ever-changing works of art to delight anyone going to post a letter. Animals, flowers, all very cheerful.

That generation were more active, happier and far better educated than later ones. The local schoolmaster came before breakfast to teach them Latin, Greek and astronomy. They also learned excellent French and German: Great-aunt Rachael taught my aunts French to such a high standard that they were moved to the top class for languages in their English boarding-school. They learned historical dates and geographical facts in rhymes that were never forgotten, and fascinating jingles came out at meals when they were over eighty.

The most important thing in the life of the family was the church, which was built partly by the Irish Church Missions – one of whose founders was my great-great-grandfather – but mostly by my great-grandfather, with the donations he extracted by sending round the following letter in 1853.

‘Therefore we His servants will arise and build.’

All ye who feel a desire that Protestantism should take root in our land, – all ye who would wish to see the blessings of CIVILISATION, INDUSTRY, CONTENTMENT, LOYALTY AND PEACE grow up in this remote and unvisited peninsula, instead of BARBARISM, SLOTH, DISCONTENT, DISAFFECTION AND TURBULENCE, a change which a knowledge of God’s Blessed Word and the inculcation of its principles, are eminently calculated to produce … It is twelve months since, relying on Him who can use weak instruments as well as strong, I laid before the public the spiritual wants of the truly primitive and interesting people of Errislannan …

I will spare you the rest, it was a long letter. What incredible conceit! And what a vivid picture those few lines give of the attitude of the Protestant landowner fired with missionary zeal. The tragedy of the Famine was only four years behind them; Connemara was dotted with ruined houses; thousands of acres were going back into bog; landlords were being murdered and the Irish Republican Brotherhood was to start its long bloody fight for freedom only eight years ahead, but families like ours survived with their eyes shut. My youth was enclosed in this pious and contented atmosphere, and it has taken a lifetime and extensive reading to discover what was happening in Ireland in this century.

The church was finished in 1855 and consecrated by Lord Plunkett, Bishop of Tuam, on July 31st. The next day in the diary has the entry, ‘George gone to the Crimea in Imperatrice,’ and inserted later, ‘6th Gibraltar, 11th Malta. Close to Constantinople, Balaklava – Genoa’. But brother George died later in India.

In the seventh century there was a village on the site of the Manor, near our good spring well. St Flannan is said to have come from the Aran Islands one day driving a cow, and asked where he could spend the night. Only on the island in the lake, he was told, the lake at that time extending to the foot of Look-out Hill. In the morning he was ensconced on what had been an island and the lake had retreated to its present level. Flannan built a small beehive church of stones and a beehive hut beside it, in which he lived. In 1684 Roderick O’Flaherty wrote, ‘No bodies are to be buried in it, or they will be found above ground in the morning,’ but the Morris family from Ballinaboy are still buried there and seem to rest peacefully. By it is a holy well with a bullaun – a hollowed-out stone – where coins, Rosaries, buttons are still placed after prayers and walking clockwise round the well. Long ago I used to draw groups of women kneeling there. There must have been a religious house on the site of the Manor, as small bits of carved stone have been found in the walls.

The family diaries indicate the astonishing amount of social life in Connemara between 1850 and the turn of the century: the calling, dining, dancing and parties; tennis with thirty-four players, picnics and boating expeditions. They drove in the carriage and pair as far afield as Westport – forty miles – visiting friends and staying the night; ‘The gentlemen walked part of the way.’ Also to Boffin Island, spending the night with the Hildebrands: ‘We danced and then slept eight girls to one room.’ Next day, ‘Back to Cleggan in rough seas, but transferred to the Adamsons’ boat and on to Kill, where we dined and stayed the night … Called on the Irelands on our way home.’ The next day, ‘We rode to Roundstone [twelve miles] to the Robinsons and called on the Hazells on the way home.’ And so on, day after day, calling or being called on. Men came to fish or shoot – ‘Hares, partridges and the simple rabbit.’ ‘Captain Palmer shot a black cat in mistake for a black rabbit.’

My great-aunts thought nothing of walking the five miles into town, or rowing the two miles across the bay. Once they rode their ponies nine miles to Shinenagh for breakfast with the Sheas and then drove to the mountains, which they climbed ‘Right to the very top in the rain. Soaked through so we stopped at a farm and sat by the fire and drank tea.’ The next day the only entry was ‘Very stiff.’

The next generation did none of these things; they could not ride, swim or row boats, which resulted in a very confined life. When my turn came I found I could easily walk into town, or row across the bay and go fishing by myself, but I had no pony or even a bicycle. Great-aunt Alice’s diary strikes a sympathetic note: ‘Rowed to town, coming home in the dark, it was very rough. Terrified and could not find my way in’ – this is exactly what happened to me several times. Nearly a hundred years later I rowed my little boat home in the dark and moored to the same rocks and walked the same path up to the house; this continuity is what makes Errislannan the most loved place in my life.

In the middle of the nineteenth century the D’Arcys were at Clifden Castle across the bay and later moved to the dower house, called Glenowen. Their descendants, the Eyres, came to the castle and were friendly enough until one night Great-uncle Walter drove Miss Eyre home in the ‘coach’ very drunk and handed her in to her angry father.

There were Blakes at Renvyle who had to leave because of poverty; the last, Miss Julia Blake, died in London of starvation. There were Mansfields at Faule, Kendalls at Emlanabehe, Hazells, Morrises, Armstrongs, Corrys, Palmers, Irelands, Browns, and, on Errislannan, Byrnes at Boat Harbour. Most impor-tant for the family was a large family of Irwins in our rectory (Drinagh) near the church. Ben was greatly fancied by Aunt Jane when they were in their teens, and Alfred was for generations a much-loved doctor in Connemara. Now all those houses are empty, ruined, or turned into hotels owned by foreigners.

Great-aunt Rachael’s diaries cover the greatest span. She tells of all the children being sent to England during the Famine, the journeys by canal boat across Ireland and later: ‘Trelford [the coachman] is very angry at doing the churning. May [the cook] has fled. Gone to America I think.’ And when her loved young cousin died at Burmount, ‘Aunt Rachael and Louisa bowed to the earth with grief, but John is happy in Heaven with Jesus in the Blood of the Lamb.’

Years later, when the Manor was being sold, I plunged my hands into those sacks in the yard at Errislannan and drew out, among nineteenth-century deeds and trivia, letters from those two great protagonists, the Duke of Wellington and his victim, Daniel O’Connell: a strange find for our stable yard. That from the Duke was to one of our ancestors, General Munro, a Waterloo friend, inviting him to breakfast ‘between one and two o’clock to meet their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess and Princess Augusta of Cambridge, and the princess Sophia Matilda … at Walmer Castle.’ Daniel O’Connell’s letter was to my great-grandfather on a business matter, but his signature was thrilling to me. In 1843 he had held one of his ‘monster’ meetings in Connemara in the fight for Catholic emancipation and the repeal of the Union. One hundred thousand people gathered round Clifden, but he stayed the night with the Martins at Ballynahinch Castle and many travelled there to meet him. There were no proper roads then so the people must have come on horses and donkeys or by sea in their curraghs or puchauns. An amazing sight it must have been, like a modern refugee camp without any of the helpers or suppliers. Our now empty harbour must have been crowded with boats. A year or two after this, Daniel O’Connell was defeated in his most glorious hour by the Duke of Wellington; he had cannons trained on one of these ‘monster’ meetings, and to avert slaughter O’Connell ordered his followers to disperse. He died a few years later during the Famine in 1847.

Another find in the sack was the notice fastened to our wall at the time of the Fenians, about 1870 when many landlords were murdered; we received only the following:

To you who pay rent by work and labour in Errislannan to Mr Wall or any other unmerciful land jobber, this manifestly proves your determination to stand antagonistic defiantly to the voice of the nation and the public press. You need not expect to prevaricate us – if you attempt to shroud in distant solitudes in crevices of rocks, in the bowles of the earth, you shall be detected. You parcel of infernal vipers we notify you to desist, desist, desist.

John Conneely Dan Val Conneely Martin

The families of the two signatories still live in Errislannan. The notice shows to advantage the vocabulary taught by the local schoolmaster. One tenant brought a calf down from the back of the hill as a present to my great-grandmother as he dared not pay rent.

With the collapse of the loft floor, the ‘coach’ was sent to be mended, but it was left out in the rain until it fell to pieces. After a century of use its loss was felt very much, not only for its shelter coming over the hill on dark nights and in bad weather; its musty blue felt seats and mirrors were tangible reminders of the past generations who wore lovely dresses and went to dances and parties; while all we knew were dreary entertainments in the parish room, dressed in black woollen stockings.

Before the coach is forgotten for ever, I must tell of one stormy night when we arrived home to see the cook, Mrs Keegan, in the light from the carriage lamps, waving her arms and screaming in at the window: ‘Murder! Murder! Pat has cut Tommie’s throat and he’s bleeding in the sink. Oh! Glory be to God I saw him, I saw him.’ The blood flowed into the sink all right but Tommie was still standing. The boy Pat was sitting at the table with the bread-knife still in his hand, his eyes like black buttons in his white face. In the dimly lit kitchen the cook was walking up and down gesticulating and shouting: ‘He called him a bastard, and why not? Isn’t he Big Biddie’s bastard found under the garden wall by Miss Edyth?’

Aunt Jane plastered Tommie’s throat and threatened him with death if he moved during the night. The next morning Pat had gone. We were very worried about him as we knew he had no money, but he found his way to Galway and joined the band of the Connaught Rangers, who were just off on their ill-fated trip to India. This must have been about 1920. The men were mostly from the West of Ireland, and when they heard of the terrible things being done to their families at home by the Black-and-Tans, fifteen of them mutinied, refusing to obey orders until the British army left Ireland. They were treated with barbaric cruelty and one, Jim Daly, was shot by firing squad: the last British soldier, I believe, to suffer this penalty. The other fourteen, by order of the court martial, were sentenced to penal servitude for life and sent, under harsh conditions, to Portland. The feeling was so strong in other Irish regiments that those in Dorset had to be confined to barracks while the prisoners were being taken through. Mercifully our Pat was not in trouble and came back to us for his leaves. Many years later Uncle George found him working as a porter at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York.

CHAPTER 2

Journeys to Dublin by Bianconi Carand Canal Boat

When winter came, my great-grandparents and the family went to Dublin, and to dances at the Castle and the Viceregal Lodge. A photograph shows Great-uncle Walter in court dress and the girls in white satin long dresses with tiny waists. There were plenty of army officers for partners, but the season was short, Connemara a long way off and they never met again. Everything at the Castle was on a fantastically lavish scale and they seem to have been unaware of the starvation and dangerous unrest that surrounded them as they made their leisurely way across Ireland in safety, though threatened at home from time to time.

These journeys were made by Bianconi car to Ballinasloe near Galway. This was a double-length side-car drawn by two horses, with a third horse waiting at steep hills to help it to the top. It carried nine or ten people, according to width, and there was a deep well between the seats for luggage. The road from Clifden to Galway must be one of the most beautiful in Ireland, winding round the foot of the mountains, among the lakes, over heather-covered moors, between banks of flaming yellow gorse, but in the last century it was little more than a track. Even in my youth I have been held up by raging waterfalls across the road, so it must have been quite perilous in the heavy four-wheeled side-car. Maria Edgeworth gives a horrifying description of the road and how the wheels had to be taken off the carriage and the whole thing carried across the streams, when she paid a visit to the Martins at Ballynahinch in 1834 at the age of sixty-seven. She describes it as the ‘haunt of smugglers, caves, murders, mermaids, duels and banshees’, and refers to ‘the wonderful ways of going on and manners of the natives’.

I remember the road being frightening, lit only by the flickering light of the candles in the carriage lamps. On a grey day when the mountains are purple, the moorland seems dark and threatening; the solitary scarlet holly and rowan trees, wings spread, seem to try to fly from the west wind, but are anchored to the ground by their slender silver trunks. Black-faced sheep stare and run away; little dark figures of men, far away, dig their turf: the silent clouds sail over the hills casting fingers of light like searchlights, turning the land to rusty red, and the gulls’ bellies shine white against the sky. All this must have been exactly the same when the family travelled that road in the middle of the last century.

Reaching Ballinasloe after the sixty-five mile drive, they went on board a canal barge which they hired to take them to Dublin; once, they shared it with the Martins of Ballinahinch. The journey took three days and was enjoyable if the weather were fine and they could walk along the tow-path with the horses. They must have been an attractive sight in their crinolines and the circular scarlet hooded cloaks which hung in the porch at the Manor for seventy years; I always slipped one on for wandering about Errislannan.

Those journeys across Ireland by canal were not as Spartan as they sound. For sixty years of the nineteenth century canals were the best form of transport; the Grand Canal Company had large comfortable hotels along their quays – at Portobello, Robertstown, Tullamore and Shannon Harbour on Lough Derg. Some had handsome Georgian façades and the one at Portobello was described in an 1821 guide-book as

a very fine edifice situated on the banks of the Grand Canal … a very fine portico and the interior is fitted up with great elegance for the accommodation of families and single gentlemen. [Note, no single ladies!] The beauty and salubrity of the situation, enlivened by the daily arrival of the canal boats, renders it a truly delightful summer residence.

The entry in my great-great-aunt’s diary refers to canal barges but most of their journeys must have been on the ‘fly-boats’, which travelled at eight miles an hour, including the time spent on the locks. The cabins were comfortable with stoves for warmth, cushioned seats, a kitchen and pantry. The slow boats had two horses; the fast ones, three. Two postilions rode on the horses armed with pistols and blunderbusses to protect the boat, and the crew comprised a captain, a steerer, a stopman, a barmaid and cabin-boy. The boats were a magnificent sight when travelling fast.

In the last half of the century the passenger services were largely given up except for the hire of barges, but freight was profitable, especially when they began to carry coal for the railways.

After the Famine, when emigration was draining the life-blood of the country away to America, the emigrants travelled west in their thousands from Dublin to Shannon Harbour by canal. The people of Shannon baked them large oaten cakes to feed on during their voyage across the Atlantic. In one year the canals carried 110,000 passengers and thousands of tons of freight; hence the great ruins of warehouses all along the way. One little item was the carrying of illegal fighting cocks and bantams, for which the company charged 6½d per stage.

By 1830 the rival canals – the Royal and the Grand – had come to an agreement to run a through service without changing boats, from Dublin to the west and back. During the 1798 insurrection in Ireland, Lord Cornwallis embarked an army in barges in Dublin and moved it to Tullamore in a day and a night. They were to meet a French force that had landed at Killala in Co. Mayo.

Wolfe Tone had persuaded Bonaparte to send troops to Killala. Only one thousand arrived, who distributed arms to unwilling Irish on the west coast, and marched on Castlebar with seven hundred men. The British were three to one against the French, but, after pillage and outrage, were in no state to fight and ran like rabbits: this became known as ‘The Races of Castlebar’. The Franco-Irish army later were overwhelmed by ten thousand British at Ballinamuck in County Longford

The old Shannon Harbour on Lough Derg is now derelict, but was used in 1913 for cargoes. Now the waters of the great lake run south down the Shannon to work the hydroelectric dam at Ardnacrusha before reaching the ocean. A plaque on the wall of the last lock leading to the Shannon reads:

The extension of the Grand Canal from Tullamore to the River Shannon being a distance of eighteen Irish miles, consisting of ten locks, three large aqueducts and fifteen small aqueducts or tunnels and twenty bridges, commenced on January 1st 1802 and opened, complete for navigation, on 25th October 1803.

A very rapid bit of work.

It is strange to think that Ireland owes its canal system to the Huguenot refugees, who were good businessmen and had come to Ireland from southern France with a knowledge of the Languedoc Canal, built in 1681. Work had been started on a canal from Dublin to Tullamore in 1756, but failed in 1771 due to bad engineering. The new company, the Grand Canal Company, first pushed one branch southwards and then in 1803 connected Dublin with the Shannon at a cost of two million pounds. It was very successful in spite of competition with the Royal Canal, which ran almost parallel a little to the north. Country districts were well served with ‘lorries’ or wagons for delivery. They were one of the first to introduce steam – and later diesel – driven barges. Now all is gone; until its recent restoration the Royal Canal was silted up and many of the branch lines were invisible.

So the family travelled in comfort for the greater part of the journey, but the long drives on the Bianconi cars must have been a trial of endurance – especially when it was raining and cold, with none of the mackintoshes we know today. Perhaps it was while sitting on those cushioned seats in the barges that they wrote their diaries: hopefully, going to town; sadly, returning with no rings on their fingers.

Judging by the diaries, my great-grandparents and their eight children thought nothing of this difficult journey, and divided their time between Errislannan and 6 Hume Street, Dublin, although some members of the family remained until the middle of the century in the previous family home, Burmount Manor on the river Slaney in Co. Wexford, where the Errislannan relations often joined them. Burmount was a beautiful house and the writer of one diary continually bemoans the fact that Errislannan was ever heard of. Jane Heather’s diary describes its tragic history:

Our ancestress Jane Worth, who lived in the early seventeenth century, was also ancestress to the Arran family. A great deal of money has been spent trying to get back some of the Wexford property that we feel convinced belongs to the Frayne side of the family. My great-great-grandfather, Major Frayne (whose uniform button and wife’s wedding ring I have), raised a contingent of men in the troubled times for England. He was thrown off his horse and drowned crossing the River Slaney at Ferry Carrig. (There is a bridge there now.) His little widow and two sons were at Burmount when the rebellion of 1798 started. The rebels came to Burmount and took the eldest son out of bed where he was ill of a fever. They dressed him in a rebel coat and held him up on a horse, and so to the Battle of Ross. Here they threw him down with a pike beside him, and owing to the rebel coat he was killed by his own side.

The second son was put in jail at Wexford, and three times he was brought out on to the bridge to be piked and thrown into the river, and each time he was saved by a Roman Catholic priest, the Rev. Father Michael Healy.

Then the boy’s mother devised a way to get him out. In those days there was a lot of illicit spirits made, which went round the country in small barrels, dressed like a woman in a red cloak, riding pillion behind a man on a horse. Mrs Frayne dressed like this, and, carrying clothes for her son, got into the jail and they came out together. When they got near Burmount they heard great lowing of cattle, and saw that the rebels had cut steaks out of the live cattle. It is hard to believe but they did worse. At Sculla Bran they put the women and children inside and set fire to the barn. The women threw out the babies but they were caught on pikes and thrown back into the flames. At Vinegar Hill they had barrels lined with nails, into which they put the people and rolled them down the hill.

These things really happened and it should be told, as those people are now held up for veneration and have monuments erected to their memory.

It was from Burmount and the Fraynes that most of our silver and better furniture came, including the famous Nelson chairs, of which more anon.

The rigours of the Dublin journey were alleviated at the beginning of this century when a railway was built from Galway to Clifden, but now there is hardly a trace left of that great engineering feat except where portions turn into a fine new road. In my youth I travelled on it many times and had to witness the heart-breaking scenes of parents saying goodbye to their children for the last time on earth as they left for America. The men clung to each other and cried aloud; the women in their big black shawls collapsed on to the ground swaying and weeping, raising cries like the keening at a funeral. The emigrants, having spent the previous night at parties, looked like death and heaven help me if they came into my carriage! Some of our Errislannan parents have parted with seven or eight of their children in this way, mostly bound for San Francisco, but now they part with the hope that the emigrants will fly back one day for a holiday, and more and more go to England and return to help with the turf and the hay.

CHAPTER 3

The Great Famine andQueen Victoria’s Visit

Before advancing further into this century, I must go back to the Famine of 1845–9, as it had such lasting effects. The ruins of the houses that were emptied in those years are dotted all over Errislannan.

Reading my family’s diaries of those terrible years, one realizes that it was a time of starvation of the poor – chiefly those in the country districts – while the rich went almost unscathed; the country landlords suffered financially but did not go really hungry. In one day-by-day diary written in Dublin by my Great-aunt Rachael, there is not one mention of famine or shortage, but in others, written in Errislannan, one reads of the terrible isolation, the helplessness to relieve horrifying distress on a small peninsula without even a horse to ride and everyone too weak to walk. My grandmother and all her brothers and sisters had been sent to England, but my great-grandmother in Errislannan collected what food she could, and some Indian corn came from the depot in Clifden, brought in carts under armed guard. She boiled it in the copper of the old laundry on the back drive and distributed it to whoever could come, but they were often too weak to leave and lay on the ground in the laundry garden, where some died.

My great-grandfather planted turnips in the meadow that encircles the graveyard by the lake. Unfortunately starving people ate them raw and died round the field. There was no one strong enough to bury them and so they remained.

In the winter of 1846–7 snow fell in November, and later there was such a heavy frost that the Errislannan lake froze over. Terrible icy winds blew over the desolate land; people had been too weak the year before to save the turf for warmth and cooking and this was not taken into account when supplies such as raw maize were sent. It was not only our people, but islanders and those from nearby headlands, that came, and lay dying along the roads. On Clare Island there were 576 deaths. Digging ditches in the years to come meant finding bones. In 1969 a grave with about fifty skeletons in it was uncovered. In all the houses on the back of our hill, only one old woman remained alive and she eventually came down to live with us. The dogs they were unable to catch and eat eventually ate them when they were dead, and these dogs were one of the worst horrors, prowling about the woods howling like wolves.

One diary entry for 1849 describes how the ladies went out in a boat to see a ship laden with ‘three hundred paupers bound for America’. The fact that it was in Clifden Bay shows that it was too small to reach America with that number of people crowding the decks; but drowning must have seemed a merciful death compared with that awaiting them at home. The great granaries on the quay in Clifden were full of corn, which was loaded under military guard and sent to England while people died of hunger in the streets.

In Clifden the Union or workhouse and the lane leading up to it were full of people, packed together, dying of starvation, the relapsing fever, typhus and pestilence. Eventually the bodies had to be burned. In 1847 the Union went bankrupt and people were living in caves, in holes in the bogs – probably the warmest homes – and shelters put over ditches. In other parts of the country, houses were pulled down by soldiers for the landlords, for non-payment of rates or rent, but I think the houses round us were deserted because they had dead people in them. In one house near the church, Rockstrow, a sow being kept for her litter ate the baby in the cradle.

The people had no savings to fall back on; the men had been paid wages of 7d a day and the women 4d, and then it was only casual work such as building out-walls round Errislannan. With no potatoes and no turf it is strange that there were any survivors. Road-works were started and the south road was built on Errislannan running out to Coronagh Harbour, but the men were too ill to continue and soon gave up altogether; I remember it being referred to as the Famine Road. The Famine also ruined nearly all the land-owners in the West. Their houses emptied and the land went back into bog.

All over Ireland from these years onwards wholesale evictions were taking place as by constant division the farms had become too small to be economic. In 1879 6000 were evicted, in 1880 10,457; and then in four years 23,000 were made homeless. I remember an old song that ran something like this:

‘Oh rise up Rory darlin’ for there’s knocking on the door.

We must leave the little cabin that we built in days of yore …

There’s no place for us in Ireland, the place is ours no more.

We must go now Rory darlin’ far away across the sea … ’

and across the sea they were sent, under most unhuman conditions; many in the holds of the ships that had just unloaded wood at Cork.

On Errislannan, being a small place, only one family was evicted, and they had two houses; one in Clifden and one on the spit of land that is almost an island. Here they had dug out a cellar where they made poteen. They thought they were safe from the police as they could see any boat coming up the bay, and the smell was carried away by the wind. They had a big black pot for a still and when the police did eventually arrive they threw this pot into the channel; we used it for many years as a turf container. The house was pulled down and the evicted family camped on our back drive in tinker-like shelters to extract pity. It was very unpleasant, but in the end they retired to their town house.

Much has been truly said about the cruelty of the absentee landlords and their agents, but not enough about the landlords who lived on their land and were fathers to their people. The D’Arcys of Clifden Castle, our next-door neighbours, suffered financial ruin through their generosity; the Martins of Ballynahinch and the Gore-Booths of Lissadill in Sligo were famous for their humanity to their tenants, but such landlords were few in numbers. In Errislannan it was taken for granted that help would be given, even after the Land Commission had taken over all the tenants in the 1920s. They were still our friends; they might want something we had, and in return do a day’s work, or bring endless presents. One common request was for ‘the loan of a shirt for the corpse’, so Aunt Jane always kept a supply – ostensibly ‘Master John’s’ – for the occasion, and every grave was lined with flowers from the Manor garden. I think this last was a mistake and not always appreciated; it spoilt the natural simplicity of the funerals. The loss of the big houses after the Famine meant loss of livelihood and great hardship for many of the people.

Errislannan survived because the family had resources other than land, but from that time on mortgages were to strangle the place and make life difficult for the future generations.

One good thing that survived for seventy years were the boys’ and girls’ orphanages, started by my great-grandmother and Mrs D’Arcy, who went round the stricken houses and collected the babies whose parents had died during the Famine. The boys were housed in a large building at Ballyconree at the end of the next peninsula; now it is a gaunt ruin, burned down by the Republicans in 1922. It was an excellent orphanage, which I knew well as I used to stay with the Master’s daughters. They did all their own farming, turfcutting up on the mountain, and had a boat for fishing. The girls’ home, which reminded me of the school in Jane Eyre, was in the D’Arcy dower house, Glenowen, in Clifden. The girls were dressed in maids’ uniforms and were sent into service at fourteen, with no knowledge of where they had come from. As these were Protestant homes, sometimes Roman Catholic relatives kidnapped the children off the side-car on their way to Ballyconree.

The Famine reduced the population from over eight million to less than five million; mostly by starvation and disease, the rest by emigration – forced or voluntary. In five years from 1846 a million people emigrated. From the workhouses were sent the old and infirm and many children while their places were filled by men who were worth feeding so that they could work: shades of the Germans’ gas-chamber selection. Everyone went who could reach a port and take ship to Canada. Diseased, naked and destitute, they were very unwelcome when they arrived, and in 1848 Canada passed legislation forbidding entry to paupers. Then good-class farmers who could pay a fare started emigrating, a new disaster for Ireland. From Cork, a thousand a week were leaving; just walking out of their unsaleable farms, leaving unpaid rates which would be levied on any purchaser. In Ballina (I quote Woodham-Smith in TheGreat Hunger)

thousands of acres looked as though they had been devastated by an enemy; in Erris seventy-eight townlands were without a single inhabitant or four-footed beast. The landlords could not deal with the farms abandoned and large arable tracts were either deserted or squatted on by paupers living in a hut or a ditch and with no chattels whatever distrainable for poor rate.

This taking of any chattel was the final cause of collapse, as without even a spade a man cannot dig turf or plant seeds or potatoes. Although no rents came in, landlords were responsible for rates and this it was that caused them to be sold out under the Encumbered Estates Act. In Connemara the last of the Martins of Ballinahinch had a rates bill of £11,000 which he could not pay after all his generosity to his people, and so the family were driven out.

Even the big towns such as Athlone were being deserted, and many streets in Dublin and Cork were empty and derelict. In Mayo a landlord wrote, ‘Thousands are brought to the workhouse screaming for food and cannot be relieved.’ The starving people became violent and even armed police could not control them. In 1848 there was an insurrection which was put down quickly and martial law declared. ‘In Westport, 26,000 people are destitute of food, fuel and clothing and 200,000 people are crowded into workhouses built for less than 100,000.’ Fever, typhus and relapsing fever were still prevalent and then came cholera, which spread from Belfast all over Ireland. There were also 13,812 cases of opthalmia, which took its greatest toll among the young: it became common to see one-eyed children.

Children and young people were committing crimes in order to get into prison or be deported. The Quakers were the best helpers but eventually their funds ran out. The English government had helped in the first two years to the tune of eight million pounds, when it was sorely needed at home, but this had dried up by 1848 and the people, by the Poor Law Act, were thrown back on the bankrupt workhouses, many of which were shut.

By 1849 Ireland had reached rock-bottom in misery, but there were 10,000 British troops in Ireland, well fed and leading a gay social life round Dublin. At this point it was thought that a visit from the Queen would be an uplift and so, in face of much opposition, it was arranged. Lord Fitzwilliam refused to have anything to do with the visit. He wrote, ‘A great lie is going to be acted here … false impressions are going to be made … then false government will ensue. I would not have her go now unless she went to Killarney workhouse, Galway, Connemara and Castlebar.’ Some hotheads planned to seize the Queen and hold her prisoner in the Wicklow mountains, but when the time came only two hundred men turned up at the rendezvous, not enough to beat the garrison, so they dispersed.

Queen Victoria was then thirty; pretty, vivacious and friendly, and although at first there were many against her, after four days she had won all hearts and vast crowds lined the streets and ran beside the carriage for miles in the country.

On 2nd August 1849 the Queen, Prince Albert and four of their children, with the ladies and gentlemen, made up a party of thirty-six. They landed from the Victoria and Albert paddle-steamer near Cork, where there were several ‘war-steamers’ to escort them. Boats crowded with people swept past the royal yacht cheering and thunders of artillery were heard. The Queen toured the beautiful harbour in the Fairy before landing at a gaily decorated pavilion, where she received Protestant and Roman Catholic clergy in equal numbers, judges in their robes and other dignitaries. On the yacht she knighted the Mayor of Cork. She graciously named the place ‘Queenstown’ and a flag was run up with the name in gold on it. (Since independence it has reverted to its Irish name of Cobh.)

The Queen re-embarked and steamed up to Cork, commenting on the beauty of the landscape. They paused to receive a salmon from the poor fishermen of Blackrock and then the Fairy came alongside the Custom House, Cork. The whole side of the building was covered with scarlet cloth embroidered with golden shamrocks, the rose and the thistle; above the entrance the famous Irish greeting which was everywhere during her tour, Céad Míle Fáilte, ‘a hundred thousand welcomes’. The steps to the water were covered in scarlet, a triumphal arch had been erected on the quay and a stand for 400 ladies under an awning of scarlet. Flags were flying, bands were playing and the artillery continued to deafen everyone. The Famine was forgotten. Queen Victoria’s own account written in her diary ran:

We landed and walked a few steps to Lord Bandon’s carriage. The Mayor preceded us and many followed on horseback or in carriages. The 12th Lancers escorted us and Infantry lined the streets. It took two hours … the streets were densely crowded, decorated with flowers and triumphal arches … the heat and dust were great. We passed one of the four college buildings that have been ordered by act of Parliament. The crowd is noisy, excitable, running and pushing about and laughing, talking, and shrieking. The beauty of the women is quite remarkable; almost every third woman was pretty, some remarkably so. They wear no bonnets, and generally long blue cloaks. The men are often raggedly dressed and wear blue coats, short breeches and blue stockings.

The next day the sea was rough and they put into Waterford Harbour for the night. The Queen and children were very seasick. The following day they arrived at Kingstown. The diary again:

With this large squadron we steamed slowly and majestically into the harbour of Kingstown which was covered with thousands and thousands of spectators cheering most enthusiastically … We were soon surrounded by boats, and the enthusiasm and excitement of the people was extreme.

More addresses and the party reached the train through a covered way where ladies and gentlemen strewed flowers.

In Dublin a miracle of camouflage had taken place. The Viceregal Lodge and Dublin Castle had been done up at a cost of £3400; more had been spent on the decorations and illuminations. Especially magnificent was Nelson’s Column at night; the lights had to be turned out at intervals so that the other illuminations could be seen. The Bank of Ireland had spent £1000 on lights. The Queen’s secretary had warned that no bills were to come in later. The procession made its way to the Viceregal Lodge among arches, decorations and huge crowds. Victoria was very touched:

At the last triumphal arch, a poor little dove was let down into my lap, with an olive branch round its neck … a never-to-be-forgotten scene; when one reflects how lately the country had been in open revolt and under martial law.

Dublin was like a city risen from the dead; it was the second city of the empire and possibly the most beautiful. Empty derelict houses were painted; muslin curtains were hung in the windows, and window-boxes full of flowers gave a misleading impression of prosperity. My great-grandfather’s Dublin house was on the route of the procession, but tantalizingly my Great-aunt Rachael’s diary has four blank pages over the days which would have been so interesting. The children had been sent to school in England during the worst of the Famine, but in 1849 in Dublin the last entry before the Queen’s visit was, ‘Papa insists that we go to Burmount for our Summer Vacation.’ Perhaps dear papa thought of the expense of fitting out so many daughters for the drawing-room at the Castle. They would have received invitations as my great-grandfather was chaplain of the Chapel Royal, and their aunt Sarah Munro could have presented the girls. One entry just after the visit says that General Munro – friend of the Duke of Wellington – had died and was buried in Dublin; later, by order of the duke, he was reburied in Canterbury Cathedral.

For the levee the Queen wore a dress of green Irish poplin lavishly embroidered with gold shamrocks, the blue ribbon and the star of St Patrick, and a brilliant diamond tiara. The gentlemen were in full-dress uniform. The Queen sat on the great gilt throne and more than 4000 people were present; 2000 were presented. She then returned to the Viceregal Lodge for dinner, an evening party and a concert.

The most popular part of the visit was the great review in Phoenix Park. The Queen left the Viceregal Lodge in an open barouche with her four children. The Prince, in the uniform of a major-general, rode a magnificent chestnut.

Carriages remained in Phoenix Park all night – many had acted as henroosts since the Union, when society forsook Dublin. Every carriage, cart or side-car was packed amidst the mass of walkers and horseback riders that filled the streets. Of the 10,000 troops in Ireland at this time – more than in the whole of India – 6000 were at this review. After evolutions by hussars and lancers and other troops, the whole body moved to the far end of the review ground, to the music of their regimental bands. The infantry with fixed bayonets, in double-quick time, charged forward with the Irish yell and British hurrah, until within twenty yards of the Queen’s carriage.

The cheers and enthusiasm were tremendous and continued all the evening as the Queen drove through Dublin to the Castle for the levee-room. The next day the welcomes followed her into the country to the Duke of Leinster’s home. She noted the raggedness of the people running beside the carriage, remarking, ‘they will do anything at a word from the Duke, he is so kind to them’.

At last the four-day gala ended and the Queen and her family embarked on the Victoria and Albert at Kingstown Pier, amidst unprecedented cheers. ‘Her Majesty paced the deck for a little time until, approaching the lighthouse, she looked towards the crowds, ran along the deck and, with the sprightliness of a young girl and with the agility of a sailor, ascended the paddlebox.’ On the summit she was joined by Prince Albert, and, taking his arm, ‘gracefully waved her right hand towards the people on the pier’. The Queen wrote, ‘I waved my handkerchief as a parting acknowledgment of their loyalty. The night was thick and rainy, and we feared a storm.’

Dublin settled back; poorer but happier. All this! And not two hundred miles away to the west were thousands of men, women and children starving and homeless.