22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

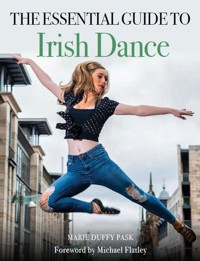

The Irish Dance genre is an essential part of the heritage and culture of Ireland. From its early roots in Celtic history, to the global growth inspired by shows such as Riverdance, to the modern- day competitive championships and Feisanna, it continues to be a vibrant and evolving dance form. The Essential Guide to Irish Dancing delves into the history and culture behind the world of Irish Dance, offering technical instruction from beginner-level to advanced, including how to prepare exciting set dances and choreograph innovative sequences. Topics covered include: Irish dance music; the fundamentals of solo dancing; traditional dance movements and set dances; Céilí dancing; competitions and careers; choreography, and finally, physical fitness and mental health.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 327

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

First published in 2022 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2022

© Marie Duffy Pask & Michael Pask 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4074 6

Cover design by Maggie Mellett

CONTENTS

Foreword

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Preface

Introduction

1.The History and Development of Irish Dance

2.How do I become an Irish Dancer?

3.Music of the Dance

4.Solo Dancing

Part One: The Fundamentals and Basic Steps in Solo Dancing

Part Two: Other Solo Traditional Dance Movements and Set Dances

5.Céilí Dancing

6.Examinations, Qualifications and Competitions

7.Opportunities after Competition

8.Choreography

9.Mental and Physical Fitness, and Health and Safety

10.Concluding Remarks

Appendix I: Suppliers of Irish Dance Wear

Appendix II: The Language of Irish Dance

Bibliography

References

Index

FOREWORD

When Marie Duffy told me she was writing a book on the A-Z of Irish dance, I knew that she would be the only person in the world that could do this! Her involvement and true dedication to the teaching and progression of Irish dance from competition to performance, from pastime to professional, makes her the undisputed expert on all things Irish dance.

Michael Flatley.

She has worked alongside me for the past twenty-five years and it has always been a pleasure. What has been refreshing for me has been Marie’s in-depth understanding of the evolution of a dancer from amateur to professional, a more complex transition than it may seem, and until the late 1990s was not an option for most. Her expertise and willingness to embrace all the possibilities for a dancer to become the best they can be, is a dream we have both shared for the next generation of dancers. At a time in the world where nobody believed in my dream of transforming Irish dancing from the rigid upper torso to the freedom of the Irish spirit using upper body movements, Marie’s belief in me and my vision made the world open its eyes to this fascinating art form.

Marie’s acute attention to detail makes this book the definitive source of information on all things Irish dance and will guide its readers every step of the way!

She is a dear friend, a true blue, and the Queen of Irish Dancing!

Michael Flatley

DEDICATION

To all my Irish dancing friends worldwide.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Throughout my life I have been privileged to know fantastic people who have been there for me through the good and in particular the bad times. It is not possible to mention everyone by name, but I know that you know who you are, and you will be forever in my heart.

I am fortunate to have been a part of many families throughout my life. I was brought up in a great paternal family with a lovely gang of brothers, and a mother and father who had big dreams for me, and sacrificed a great deal to help me make them happen.

I will always be indebted to the Maoileidigh family, and the teachers, dancers and parents at the Inis Ealga Dance School in Dublin where I started my Irish dancing teaching education.

Also, my thanks to all those who helped me establish The Marie Duffy Dance School, to all the dancers who attended classes, and to those who went on to win championships all over the world. Also to my friends from the Irish dancing world in Dublin who supported me throughout this period, in particular Brendan O’Brien, Eugene Harnett and Isabella Fogarty, and all the colleagues with whom I worked in CLRG over fifty years.

Sincere thanks to the Board of Management of CLRG for allowing me to use extracts from many of their articles and publications to assist with the compilation of this guide. Also to Dr John Cullinane and Orfhlaith Ni Bhriain, both renowned authors and members of An Coimisiun, for their contributions on Irish dance history, the Gaelic League, Irish vocabulary and set dances.

I have had a fabulous, fulfilling life through Irish dancing, culminating in working for one of the best Irish dance shows in the world: ‘Lord of the Dance’. I will never forget the opportunity Michael Flatley gave me to join the show, and am profoundly grateful to Michael and Niamh for their close and continuing friendship over the last twenty-five years. Also a big thank-you to all the cast members, musicians and production staff whom I met and worked with during my time with Lord of the Dance. We had a great adventure all over the world, with an abundance of excitement, dramas, laughs and tears. Special thanks to Bernadette Flynn, Damien O’Kane, Tom Cunningham, James Keegan, Aisling Murphy, and all the other leads and dance captains I had the pleasure to work with.

I am hugely indebted to my very close friends Hilary Joyce Owens and Barry Owens for all their help, advice, monitoring, proof reading and contributions on music and dance over the last eighteen months. Also to their daughter Ella Owens, a fantastic dance pupil and talented model, who kindly agreed to help us with most of the photographs for the guide, taken by our professional photographer, Grant Parfery from Glasgow.

Marie, Hilary and Team Céim Óir celebrating at the Worlds in Glasgow 2016.

Marie Duffy Pask at home.

In addition, thanks to Greg at GS Photos in Gerrards Cross for his help in scanning many of the photographs used in the guide.

I am also deeply grateful for the assistance provided by the teaching staff and dance pupils of Scoil Rince Ceim Óir, for many of the photographs, particularly those used in the chapter on céili dancing. Similarly, my thanks to Fernanda Faez, from Brazil, studying for a MA at the University of Limerick, for her photographs, and her insights into the choreographic work combining Irish and Brazilian dance.

It is impossible to mention everybody who has helped me over the years, but specifically I wish to thank my good friend James McCutcheon for all his diligent work as Chairman of the Marie Duffy Foundation, and the tireless efforts he has made to contribute to its success. Also many thanks to Michael O’Doherty, Mary Kerin, Peter O’Grady, Bernadette Flynn, James Moran and Sean Hennigan for their help and contributions to Chapter 9, Health and Safety for Irish Dance Schools.

Thank you to Mona Lennon, John Carey, The Academy Boys and Paula’s Wigs and Blings for the use of their photographs in the céilí dancing and headwear sections of the guide.

Finally an enormous thank-you to Mike Pask, my husband, without whose vision, help, encouragement, tenacity and hard work this guide would never have been completed.

PREFACE

Marie is one of the best choreographers in the world. She is like my twin sister. I will love her forever.

Michael Flatley

I was born on the Cashel Road, Crumlin, Dublin, in 1945, a daughter in a family of seven brothers. My dancing career began at the age of six with dance teacher Maitiu O’Maoileidigh at the world-famous Inis Ealga Dance School in Dublin. By the age of thirteen I had started to create steps for the dance class. Having passed the TCRG exam at the age of twenty, I continued as co-director and teacher at Inis Ealga alongside Maitiu. During this time the school enjoyed success in every category, in every age, and in both the male and female sections at the All Ireland and World Championships, winning over 400 titles in total. The school also won the gold medal for Ireland at the Folk-Dance Olympics in Dijon in 1981. In 1988 I decided to set up the Marie Duffy Irish Dance School in Dublin, which enjoyed continuing success throughout the world and particularly at all ‘Majors’ – the highest level in competitive dancing.

Marie Duffy Pask relaxing.

Lord of the Dance cast performing on a European tour.

My dance show career began in 1996 when I was invited by Michael Flatley to work on Lord of the Dance as Dance Director and Associate Choreography. This was followed by Feet of Flames (1999) and Celtic Tiger (2007). I was also involved with the production of all the Lord of the Dance and Celtic Tiger videos. I have travelled all over the world with Michael’s shows, touring Taiwan in 2009 with Feet of Flames, and around Europe in 2010 with The Return of Michael Flatley Tour.

Throughout this period I also worked on many prestigious events including The Prince’s Trust and the Ryder Cup in the UK; the Oscars in Los Angeles; Prince Albert’s Red Cross Ball in Monaco; and more recently for HRH Prince Charles at Buckingham Palace. Television shows include Dancing with the Stars and Superstars of Dance in the USA; and Tonight’s the Night, Strictly Come Dancing and Britain’s Got Talent in the UK; as well as Irish dance and music shows, including Irish television’s Beirt Eile and Club Ceile.

As an adjudicator and examiner for CLRG I have judged and examined competitions and exams all over the world, and have been an external examiner for the graduate and masters’ courses for Irish Music and Dance at the University of Limerick. I have served on CLRG continuously since 1969, and on many occasions have been the Vice President for England. At the 2011 World Championships, held in my home town of Dublin, I was presented with the first ever Lifetime Achievement Award, which recognized my dedication and contributions to the world of Irish dance and culture.

Marie’s CLRG Lifetime Achievement Award with Sean McDonagh and Éilis Uí Dhálaigh (née Nic Shim).

Later that year, I and my husband set up the Marie Duffy Foundation, a charity formed to help the Irish dancing community. The MDF is a not-for-profit organization to help young dancers follow their dreams and achieve their full potential in Irish dance. The Foundation offers grants to encourage and stimulate creativity, flair and entrepreneurship in the promotion of Irish dance skills and performance.

A Marie Duffy Foundation flysheet.

In March 2015 I retired from Lord of the Dance after twenty years of unbroken service and returned to my first love: teaching Irish dance to the next generation of dancers. I joined Hilary Joyce Owens and her dance school, Scoil Rince Ceim Óir, based just outside the west of London as a dance teacher. Later in 2015, partnering with Eddie Rowley, I wrote my autobiography, Lady of the Dance, which was published in March 2017. However, my story has not ended yet – as is the motto of our Foundation:

We go onwards and upwards, improving all the time!

Ar aghaidh linn í bhfeabhas

INTRODUCTION

Consciousness expresses itself through creation. This world we live in is the dance of the creator. Dancers come and go in the twinkling of an eye but the dance lives on. On many an occasion when I am dancing, I have felt touched by something sacred. In those moments I felt my spirit soar and become one with everything that exists.

Michael Jackson

An innovative modern interpretation of an Irish dance movement in 2021.

BACKGROUND

Ireland is known throughout the world for its dancing. The Irish dancing genre is a very important part of the heritage and culture of Ireland together with traditional Irish music, Irish language and Gaelic sports such as hurling and Gaelic football.

Whilst the origins of Irish dancing are uncertain, it is likely that it originated with the Celts and Druids who roamed the Irish countryside before the advent of Christianity.1 Over the centuries dancing progressively evolved to the form it takes today. Although originally it was a social pastime, in recent times, and particularly over the last 100 years, it has evolved into a global dance form and is actively performed in over thirty countries in five continents. The nature of Irish dance has therefore developed and adapted over recent years to accommodate and reflect changing attitudes and the demands of this wider audience and participants. Nevertheless, it still retains many of the traditional ethical values and dance steps practised in the early days. The control and regulation of worldwide dance schools and competitive events are still based in Ireland, thus ensuring that in the future Irish dancing will continue to be centred in Ireland.

The teaching of Irish dancing is an increasing and regular extra-curricular activity in numerous Irish schools, and is a practice that has expanded into the UK and beyond. The early introduction of dance lessons at infant and junior level has provided a continuous supply of youngsters to the specialist professional Irish dance schools that have grown worldwide in the last thirty years. In recent years the phenomenal growth and globalization of the art form has also been inspired by the world-wide television exposure of Irish dancing at the Eurovision Song Contest, held in Ireland in 1994. This growth has been further fuelled by the subsequent, universally popular, successful dance shows that have been initiated in recent years.

CONTENT

This guide has been formulated to appeal to all members of the Irish dancing community. It offers a basic introduction for newcomers and novices, and also provides comprehensive and practical instruction for existing Irish dancers, at all levels, from beginners to top level championship dancers. It will provide an invaluable reference manual for Irish dance teachers, dance schools and dance and choreography students. At the same time it is hoped that it will be of great interest to all parents, Irish dance fans and enthusiasts all over the world. It therefore offers a dialogue that encompasses all aspects of the art of Irish dancing from its early beginnings to the modern day, and describes how it has developed globally whilst maintaining the core elements of Irish language, music and culture.

A typical modern Irish dance school in action in 2021.

Our story starts with the early beginnings and history of Irish dance and music, dating as far back as the 1600s, and then summarizes the most significant developments since those days to modern times. The changes and advances in dance music, dances and dancing are discussed. In addition, the changing role of the dance master and the evolution of teaching methods are highlighted, together with the influence of innovative musicians and bands and the development of musical instruments. Other major changes in costumes and new fashions to the present day are also outlined.

Moving on, we pose and answer the basic question ‘How do I become an Irish dancer?’.

First, the answer to this is dance schools – what they do, and why, where they are, and what is involved.

The key dance steps and formations are discussed in detail, and the main elements of solo dancing, céilí dancing, figure choreography and show dancing are featured. The importance and basics of Irish dance are examined, such as posture, use of the arms, time and rhythm. As with most dance genres, a unique language is used in Irish dancing, and a list and explanation of the most commonly used words and phrases is included. Newcomers to Irish dancing are always keenly interested in the dance wear worn – what it is and when it is worn. The following main fashion items are therefore covered:

Shoes: A description of the types of shoe commonly used for different dance – where to get them, and typical costs.

Dresses: The types of dress commonly used for different dance forms – where to get them and typical costs, from simple tunics to championship dresses.

Headwear: The various types of wig and alternatives – when to wear them and where to buy them, and typical costs.

Make-up: Advice on the best techniques, and how to use make-up to enhance your appearance and appeal.

Musicality in Irish dance is explored, together with an explanation of the critical music terms as they relate to Irish dancing. The music is an integral part of Irish dancing, and a unique library of scores has evolved over the years – the one doesn’t exist without the other! It is essential that the Irish dancer has an appreciation and understanding of how important the music is, and how the various tunes relate to the dance.

The aspiring dancer is guided through all the key elements involved in the specific dance steps, music formations and patterns that feature in solo dancing, céilí dancing and figure choreography at all levels. These are presented in an easily understandable way with the aid of sketches and photographs.

Modern Irish dancing is highly professional, and a section is therefore included on teacher and adjudicator qualifications – what they are, what you need to know, how to apply to get them, and most importantly how to be successful. The guide then explores the worlds of competitive and show dancing, with many practical tips and a great deal of advice on how to succeed in these fields. A range of other educational and career opportunities potentially open to Irish dancers is identified for those wishing to remain in Irish dancing when their competitive careers are over.

Irish dancing is part of our heritage and culture, but it has become a very athletic pastime, and in conjunction with some notable contributors, the importance of factors such as diet, training, preparation, mindset and how to succeed is discussed. ‘Best practice’ in these essential areas is defined. The guide also provides a comprehensive reference manual for dance schools and dance teachers in the management and running of their schools, particularly with respect to child protection and health and safety matters.

HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE

I truly hope that The Essential Guide to Irish Dance will become the instructional bible for all those involved in Irish dancing at all levels. To the newcomer it can be used as a road map into dance to help them become an enthusiastic social dancer, or as a comprehensive manual to establish a professional career in the world of dance. To the championship dancer it can be used to develop a greater understanding of the intricacies of advanced steps, to help them appreciate the artistic qualities necessary to prepare exciting set dances, and above all show them how to choreograph that exclusive and innovative piece of Irish dance.

An early shot of Irish dancing at a crossroads on the outskirts of an Irish village.

To the dance teacher and dance school it can be used as a textbook on all aspects of Irish dancing, from the first steps, through céilí dancing, and to the ultimate challenge of choreographing innovative figure dances and dance dramas for world championships. In addition it will provide schools with the detail and procedures necessary to obtain formal dance qualifications. Finally, the reader will find invaluable advice and programmes on other crucial aspects such as musicality, and the influence of body and mind, all of which will enable dancers to achieve their full potential and fulfil their dreams in the world of Irish dance.

CHAPTER 1

THE HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF IRISH DANCE

Dance is the timeless interpretation of life. Through synergy of intellect, artistry and grace came into existence the blessing of a dancer.

Shah Asad Rizvi

Lord of the Dance performing to an excited audience during the return of a Michael Flatley tour.

HISTORY

Opinion is divided as to the exact origins of Irish dance. However, what is certain is that it has been around in some form for centuries, although its earliest form would be far removed from modern-day Irish dance. I have researched the history of Irish dance for this guide, and have pieced together extracts from a number of sources to provide a possible picture of the evolution of the dance form to what it is today.

The Early Records

But when and how did it all start? It is likely that the early history of Irish dance grew from a variety of factors, such as migration, wars and invasions over the centuries, resulting in a significant change in the population demographics. The arrival of these foreign nationalities introduced a variety of new cultures, including dance and music, that were ultimately to herald the birth of Irish dancing in its earliest form. Clearly the history of Irish dance is interwoven with the overall history of Ireland itself, and it is likely that influences resulted from the four most recent civilizations prevalent in Ireland, namely the Druids, the Celts, the Vikings and the Anglo-Normans.

There are only vague references to the early history of Irish dancing. For example, there is some, albeit sketchy, evidence of the Druids dancing in religious ceremonies in which they worshipped a number of idols such as oak trees and the sun. In addition there is evidence that extracts from some of their circular dances survive in the ring dances of today.2 So maybe this can be considered as the start of dance in Ireland.

It is generally accepted that the Celts arrived in Ireland around two thousand years ago, bringing with them their own folk dances and music – another possible influence on dancing in Ireland. Then in about the fifth century, in spite of the conversion to Christianity in Ireland, the indigenous peasants continued to retain the same qualities in their music and dancing.

The Vikings first invaded Ireland in AD795, when a small group of Norse warriors attacked a monastery on the east coast. They plundered the monastery of its valuables, such as relics, and laid them to waste. The history of the Vikings in Ireland spans over 200 years, and although it can be considered shortlived, the Viking invaders did make important contributions to the Irish way of life: they settled, intermarried, and shared their culture with the Irish, and this almost certainly included music and dance.

Following the collapse of the Viking era, the Anglo-Norman conquest of Ireland began with the Anglo-Norman invasion in 1169, and this brought Norman customs and culture to Ireland. These included the Norman dance known as ‘the Carol’: this combined singing and dancing and featured a circle of dancers, and was regularly performed in Irish towns.2

The ‘Ireland’s Eye’2 identifies a number of possible forerunners to today’s dances. Three Irish dances often mentioned in sixteenth-century articles were notably the Irish Hey, the Rince Fada and the Trenchmore (see below). An early reference to dance is contained in a letter written by Sir Henry Sydney to Queen Elizabeth I in 1569, which spoke about magnificently dressed and first-class dancers performing enthusiastic Irish jigs in Galway. He reported that the dancers were in two straight lines, which perhaps suggests they were performing an early version of the long dance.

During the mid-sixteenth century dancing was becoming increasingly popular, with regular performances in the newly built castles and stately homes. The Hey was very popular at the time, and involved the female dancers winding in around their partners – an early version of the modern-day reel. Another popular dance was the Trenchmore, which was adapted by the ‘English Invaders’ from an old Irish peasant dance. It was common that when royalty arrived in Ireland, they were met by women performing local dances. Typically, three people, holding the ends of a white handkerchief, stood abreast: then advancing to slow music, they were followed by dancing couples. The tempo of the music then increased, allowing the dancers to break out into a range of other dance formations.2 Dancing was also regularly performed at wakes, held to remember and celebrate the life of a departed soul. The mourners followed each other in a ring round the coffin, dancing to the bagpipe music popular at the time.

There is also some documentary evidence that dancing was widespread throughout rural Ireland at the start of the seventeenth century. It is at this time that the Irish word for dance emerged: ‘rince’. An earlier report also mentioned that Irish dances closely resembled English country dances, further confirming the early English influence on the development of Irish dance. The distinctive hornpipe rhythm of the Irish dance tradition had developed by the 1760s, and with the arrival of the fiddle from the European continent, a new class of dance master began to emerge.

The development of traditional Irish dancing steps and formations almost certainly grew in association with the trends in Irish music. The features commonly associated with Irish dance were born at this time: the local dancing venues were usually small, and often dances were demonstrated on table tops, where space for expansive movement was inevitably restricted. Consequently it was necessary to hold the arms rigidly at each side of the body, given the lack of space for lateral movement. This is possibly one of several credible explanations for this highly visible characteristic of Irish dancers. In time, larger dance venues became available, and so there was greater opportunity to include more movement in and round the dance area.

The Irish Dance Master

You dance love, and you dance joy, and you dance dreams. And I know if I can make you smile by jumping over a couple of couches or running through a rainstorm, then I’ll be very glad to be your song and dance man.

Gene Kelly

As mentioned earlier, the advent of the dance master occurred around the end of the 1700s, and travelling dance masters regularly taught across rural Ireland as late as the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. ‘Ireland’s Eye’ highlights the role and importance of the dance master. He was a wandering dancing teacher who travelled, within an area, around the many villages teaching dance to peasants. They were flamboyant characters who wore bright clothes and carried staffs.2

Group dances of a very high standard were developed by the masters to hold the interest of their less gifted pupils and to give them the chance to enjoy dancing. Solo dancers were held in high esteem, and often doors were taken off their hinges and placed on the ground for the soloists to dance on. Every dance master had his own district and never encroached on another’s territory. However, it was not unknown for a dance master to be kidnapped by the residents of a neighbouring parish. When dance masters met at fairs, they challenged each other to a public dancing contest that only ended when one of them dropped with fatigue. Several versions of the same dance were to be found in different parts of Ireland. In this way a rich heritage of Irish dances was assembled and modified over the centuries. Today, jigs, reels, hornpipes, sets, half sets and step dances are all performed.2

Early Costumes

Irish dancing dresses have changed dramatically over the years. Dancers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries wore their ‘Sunday best’, simply wearing the outfit that they normally wore to church. Typically, early costumes were made of hand-woven tweed fabrics. The costumes were loosely based on the leine (tunic) and the brat (stole or cape), as depicted in images from eighth-century illuminated Irish manuscripts.1

Dancers started to develop more formal dance wear from around the early 1900s. In the mid nineteen-fifties dresses were based on the Irish peasant dress worn two hundred years ago. Most of the dresses were adorned with hand-embroidered Celtic designs and copies of the Tara brooch were often worn on the shoulder. The brooch held a cape that fell over the back.

Dance costume of the 1950s showing a cape and Tara brooches. Marie’s first dance costume!

Development of women’s and men’s costumes in the 1960s: longer sleeves, Irish wool dresses and more Celtic designs for the women’s dresses, and Irish tweed jackets and wool socks for the men.

Each school of dancing has its own distinct dancing costume. From the 1940s onwards one of the ways in which dance schools defined themselves was through the wearing of class costumes with specific colours and embroidery motifs. These simple knee-length dresses with long sleeves and full skirts had embroidery on the skirt, bodice and cape, with crochet lace collar and cuffs worked in cotton. For male dancers it was common to wear a kilt, with shirt and tie, under a wool blazer.1

Major changes to dresses in the early 1980s with the use of velvet for dresses, deep Irish lace crochet collars, and more elaborate Celtic embroidery.

World céilí champions in the 1990s: the Marie Duffy School.

World-class style of costume from the early 1980s.

World-class style of costume from the late 1980s.

World-class style of costume from the early 1990s.

World-class style of costume from the late 1990s.

In the 1970s and 1980s solo dancers began to wear heavy A-line dresses embroidered with a variety of Celtic patterns. The dancing dresses of today are designed to the dancers’ individual taste, and each one is unique. Different colours, patterns and materials ensure that each solo dancer stands out from the crowd. Apart from dresses, wigs are also worn by dancers, and fake tan, make-up and tiaras are also commonplace. This is vastly different from the early 1900s when the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) was formed to promote Irish culture and heritage:3 then the design of the dresses was based on the style of dress worn by Irish peasants. However, the Irish dancing industry has moved with the times, and large competitions (feiseanna) are held in huge arenas and theatres complete with proper stages and lighting.

Originally, the dresses worn by women were copies of the traditional Irish peasant dress; they were adorned with hand-embroidered Celtic designs based on the Book of Kells and Irish stone crosses. The dancers of today who compete at country and world level need to stand out from the crowd with their flamboyant dresses, fake tan, make-up and tiaras! The material has changed from Irish wool to velvet and the lightweight materials of today. Embroidery has gone out of fashion, and the addition of plenty of sparkles and ‘diamonds’ is far more popular today.

There are two types of costume traditionally worn by boys who compete in Irish dancing competitions: a kilt or long black trousers. Kilts have been worn for many years, but nowadays the dancers prefer to wear long black trousers when competing, with an embroidered waistcoat or jacket.

As you can see from the photographs, today’s dresses have changed dramatically from those worn in the early years. The success of the World Championships over the last fifty years has fuelled a revolution in costume design for both females and males. The popularity of curly wigs and elaborate dresses shows no signs of diminishing, and has led to a growth industry for commercially produced Feis costumes. For grade competitions the costumes are simpler and more traditional in style.1

Irish Dance Music

Irish dance and the music of Ireland have been inextricably linked over centuries. An assortment of instruments has provided the music for dancing throughout this period, and these are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

Historically the traditional accompaniment for Irish dancing was a harp and bagpipes, or just singing, known as port a beil. However, as the dances became more complex, so did the music, and there is a now a wider variety of music and instruments to accompany the music. Some typical Irish instruments include the fiddle, the bodhran (a handheld drum), the tin whistle, the concertina, the button and piano accordions, and the uilleann pipes.4

In the seventeenth century bagpipers and harpers were the principal musicians – but when they were prevented from playing in public by legislation, an assortment of other musicians provided the beat. Many of these musicians were blind or had other physical disabilities, and music offered them a reasonable regular income. In later years the harpers teamed up with the dance masters for their regular visits and dance classes.

From the end of the eighteenth century dancing at wakes was another familiar sight. The mourners would follow each other in a ring round the coffin to the music of the bagpipes. When no instrument was available the lilter provided the music. Lilting, or port a beil, is a unique musical sound produced with the mouth.5 The music was never written down, and musicians played and learned tunes by ear. Their tunes were passed from one generation to the next. They must have had excellent memories as a skilled musician could play any one of several hundred tunes on request.5

World-class style of costume from the 2020s.

The majority of Irish jigs are native in origin and were composed by pipers and fiddlers in conjunction with the dance master. In addition, some of the tunes were rearrangements of English or Scottish tunes, for example the ‘Fairy Reel’, which was composed in Scotland in 1802, became popular in Ireland a century later. Often, many dance tune titles had no musical connection with the actual tunes – the musician often looked around his immediate environment for inspiration when naming a composition.

Music at céilíthe today is provided by a céilí band, with musicians playing an assortment of instruments including the fiddle, drums, piano and accordion.5 Live music is always employed at registered feiseanna (dance competitions), usually with one or two accomplished musicians playing the music.

Formation of the Gaelic League

In 1893 the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) was founded as an organization to promote and encourage all aspects of Irish culture in Ireland. The primary purpose was to promote a national pride in Irish language, literature, music, song, dance and sports.3 Although the promotion of dance and music was not the primary object of the League, it was at that time that dancing was referred to as Irish dancing and the dances were termed the national dances of Ireland.6

Prior to the Gaelic League, formal dance classes were centred round rural areas such as Cork, Kerry and Limerick. The League spawned a desire for more Irish dancing, for entertainment, exhibition and competition. It organized formal competitions, lessons and rules. This resulted in an increased demand for more and regular dance classes, including a geographic expansion into places such as Dublin and London. More often than not dance classes were held in conjunction with Irish language classes, particularly outside the traditional Irish centres. As the League grew in popularity in the dance world it introduced regular weekly dance classes; dance competitions called feiseanna; regional, national and international championships called oireachtaisi; and special costumes and céilí dances for both social and competitive occasions.6

The League’s interest in and guidance for the control of Irish dancing continued from its inception in 1893 through to the 1930s. However, in the late 1920s behaviour at feiseanna deteriorated, and the local dancing teachers’ associations appeared to be unable to control this. Accordingly, the League became even more involved in the administration of Irish dancing, and after a series of initiatives, finally set up Coimisiún an Rinnce (the Dancing Commission) on 8 March 1930. Ultimately responsible to the Gaelic League, this commission was responsible for the administration of Irish dancing, both solo and figure dancing, throughout Ireland. The title remained unchanged until 1943 when it was modified to An Coimisiún le Rincí Galelacha (CLRG), a title it has retained to this day.6

THE GROWTH OF IRISH DANCING GLOBALLY

The world-wide success of Riverdance and Lord of the Dance has placed Irish dance on the international stage. Today, dance schools worldwide are filled with young pupils keen to imitate and learn the dancing styles that brought Jean Butler and Michael Flatley international acclaim. Today there are many opportunities to watch, enjoy and practise Irish dancing. It is still a regular part of social functions. Dancing sessions at céilíthe are usually preceded by a teaching period where novices are shown the initial steps. During the summer months, céilíthe are held in many Irish towns. Visitors are always welcome to join in, and with on-the-spot, informal instruction, anyone can quickly master the first steps and soon share the Irish enthusiasm for Irish dance.2

The growth of Irish dancing since the formation of CLRG has been phenomenal. Initially very much Irish, and to a smaller extent British based, the organization became an international body in the 1960s and 1970s when it registered its first teachers from America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Examinations in both Ireland and the New World countries significantly increased in this period as international travel became cheaper and more readily available. The number of dance schools registered with CLRG also dramatically increased, usually in traditionally Irish-based communities, and as a result there were significant increases in dancer numbers. This growing globalization led to the first Irish Dancing World Championships in 1970.

Mixed céilí team costume style in the early 1960s.

This further fuelled the huge increases in the number of schools and dancers, as the international appeal of a truly top-class competition generated huge interest. The first World Championships, held in Dublin, attracted entries from the USA, Canada, England, Scotland and Ireland. This prestigious annual event was scheduled to celebrate its fiftieth anniversary in Dublin in April 2020, but unfortunately was cancelled due to the Covid 19 pandemic. By this time the international appeal and interest in Irish dancing had grown to such an extent that competitors from no fewer than thirty countries were registered for the event. Thankfully the event took place in Belfast in April 2022.

New Irish dancing schools and dancers have sprung up in east and west Europe, Russia, China, Taiwan, South Africa, Mexico and Latin America in the last ten years. There are currently over 2,300 Irish dance teachers registered with CLRG, and an estimated 500 dance schools world-wide. Over 5,000 competitors were expected to compete at the 2020 World Championships, attracting an estimated audience of around 40,000.

Present-day ladies’ team costume style.

The Role and Growth of Competitive Dancing

The Irish word céilí originally referred to a gathering of neighbours in a house intent on having an enjoyable time, dancing, playing music, singing and storytelling. Today it mainly refers to an informal evening of dancing. Céilíthe are held in large towns and country districts where young and old enjoy group dances together. The céilí can be traced back to pre-famine times, when dancing at the cross-roads was a popular rural pastime.

These dances were usually held on Sunday evenings in the summer when young people would gather at the cross-roads. The music was often performed by a fiddler seated on a three-legged stool with his upturned hat beside him for a collection. The fiddler began with a reel such as the lively ‘Silver Tip’, but he had to play it several times before the dancers joined in. The young men would be reluctant to begin the dance, but after some encouragement from the fiddler, the sets of eight filled up the dancing area.2