Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polaris

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

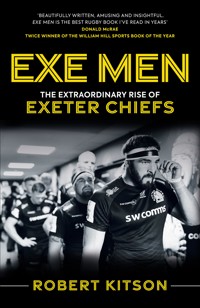

Winner of the Telegraph Sports Book Awards Rugby Book of the Year Among the best stories in modern British team sport has been the rise of Exeter Chiefs. How, exactly, did an unfashionable rugby team from Devon emerge from obscurity to become the double champions of England and Europe? What makes them tick? What are their secrets? Exe Men is a compelling story of regional pride, fierce rural identity, larger-than-life local heroes, remarkable characters, epic resilience, big city snobbery, geographical separation, steepling ambition and personal sacrifice which will strike a chord with anyone who enjoys a classic underdog story. This is not any old rugby book, it is the inside story of Exeter's incredible journey from the edge of nowhere to the summit of the English and European club game.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 494

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

EXE MEN

‘A beautifully-written, amusing and insightful book that gets to the very heart of Exeter Chiefs – a rugby club with one of the most remarkable stories in British sport. Exe Men is the best rugby book I’ve read in years’

Donald McRae, twice winner of the William Hill Sports Book of the Year

‘Forensic, funny, captivating, a story told with relish as well as insight’

Mick Cleary, The Telegraph

‘No Exeter fan should be without this book, nor any sports fan who loves a fairy tale grounded in professionalism. Splendid stuff’

Stuart Barnes, The Times

‘Exeter Chiefs – the community club that grew into a European giant. This is how they did it. A quite brilliant combination of great story and great storyteller’

Tom English, BBC Sport

‘Beautifully told, this is a rare insight into the remarkable rise of the Chiefs, from their homespun roots to the pinnacle of European rugby – surely one of the most heart-warming tales in all of British sport’

Alastair Eykyn, BT Sport

‘Punchy and penetrative, Robert Kitson has done justice to one of sport’s greatest stories. If you don’t already love Exeter, you will now’

Alan Pearey, Rugby World

‘So much more than a rugby book and full of genuinely funny anecdotes, this is a read for anyone interested in building a winning team’

Chris Bentley, Express and Echo, Exeter

EXE MEN

THE EXTRAORDINARY RISE OF

EXETER CHIEFS

ROBERT KITSON

First published in 2020 by

POLARIS PUBLISHING LTD

c/o Aberdein Considine

2nd Floor, Elder House

Multrees Walk

Edinburgh

EH1 3DX

www.polarispublishing.com

Distributed by

ARENA SPORT

An imprint of Birlinn Limited

Text copyright © Robert Kitson, 2020

ISBN: 978-1-913538-01-9

eBook ISBN: 978-1-913538-02-6

The right of Robert Kitson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

The views expressed in this book do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions or policies of Polaris Publishing Ltd (Company No. SC401508) (Polaris), nor those of any persons, organisations or commercial partners connected with the same (Connected Persons). Any opinions, advice, statements, services, offers, or other information or content expressed by third parties are not those of Polaris or any Connected Persons but those of the third parties. For the avoidance of doubt, neither Polaris nor any Connected Persons assume any responsibility or duty of care whether contractual, delictual or on any other basis towards any person in respect of any such matter and accept no liability for any loss or damage caused by any such matter in this book.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Designed and typeset by Polaris Publishing, Edinburgh

Printed in Great Britain by Clays, St Ives

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

1. ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST

2. GET ON, EXE!

3. TAKE ME HOME, COUNTRY ROADS

4. THE SPEED MERCHANT

5. WAITING FOR THE GREAT LEAP FORWARD

6. ROAD WARRIORS

7. CHARIOTS OF FIRE

8. THE HARDER THEY COME

9. INCH BY INCH

10. THE MEMORIAL HEIST

11. READY FOR THE CHOP

12. SOUTH COAST OFFENSE

13. MODERN FAMILY

14. PROPER JOB

15. TOOT, TOOT!

16. ROOTS AND WINGS

17. KNOCKING ON HEAVEN’S DOOR

18. THE INNER GAME

19. MEN IN BLACK

20. FIGHT FOR ALL

21. OUT OF DARKNESS

22. SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER

23. THE EXE FACTOR

APPENDIX I: FIRST TEAM PLAYERS SINCE 2010

APPENDIX II: REGULAR SEASON PREMIERSHIP RECORD

APPENDIX III: HONOURS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

List of Illustrations

The 1905 All Blacks kick for goal during their match against Devon at the County Ground. Dave Gallaher’s tourists won the match 55–4, which an incredulous sub-editor reported as a 55–4 victory for Devon.

A vintage postcard featuring the County Championship replay between Devon and Durham at Exeter in1907. The Championship was shared between the two teams. Getty Images

At Redruth in 1973, among them John and Paul Baxter.

Eight Devon players were selected to face the touring All Blacks

The way they were. Exeter’s team, including John Baxter (front row, far left), Bob Staddon (front row, fourth from left) and John Lockyer (middle row, far left), for the Devon Cup final against Torquay Athletic in April 1971. Exeter won 35–3.

The main stand at the County Ground. The Tribe, rugbynetwork.net

Rob Baxter plays his last game at the County Ground in 2005. Phil Mingo/Pinnacle Photo Agency

Gareth Steenson passes the ball during the Championship playoff final match, first leg, between Exeter Chiefs and Bristol at Sandy Park on May 19, 2010. David Rogers/Getty Images

The party starts in the Chiefs’ changing room after defeating Bristol in the Championship final at the Memorial Stadium on 26 May 2010 to secure promotion to the Premiership for the first time in their history. Stu Forster/Getty Images

James Phillips wins the ball for Exeter as the Chiefs make their Premiership debut against Gloucester at Sandy Park on 4 September, 2010. Hamish Blair/Getty Images

Richard Baxter (left), John Baxter (centre) and Rob Baxter pictured on their farm in Devon in 2020. They played over 1,000 first-team games for Exeter between them. Phil Mingo/Pinnacle Photo Agency

Tom Johnson and Jack Nowell hold the Triple Crown trophy after England’s victory over Wales at Twickenham during the 2014 Six Nations. David Rogers/Getty Images

Dean Mumm lifts the LV=CUP after beating Northampton Saints at Sandy Park in 2014. Mike Hewitt/Getty Images

The Chiefs parade through the streets of Exeter with the LV=CUP trophy. Phil Mingo/Pinnacle Photo Agency

Jack Nowell at Newlyn Harbour. Tom Jenkins

Tony Rowe celebrates receiving the Freedom of the City of Exeter in September 2015 by driving a flock of sheep through the city centre. Gary Day/Pinnacle Photo Agency

Gareth Steenson kicks the match-winning penalty against Wasps in the 2017 Premiership final at Twickenham. David Rogers/Getty Images

Champion Chiefs. Jack Yeandle (left) and Gareth Steenson (right) lift the 2016/17 Premiership trophy. Dan Mullan/Getty Images

Thomas ‘the Tank Engine’ Waldrom celebrates at full time with his two sons. Phil Mingo/Pinnacle Photo Agency

Tom Johnson, Ben Moon, Matt Jess, Haydn Thomas, Phil Dollman and Gareth Steenson: the ‘Originals’ who have all shared the incredible journey from the Championship to the summit of the English game. Phil Mingo/Pinnacle Photo Agency

Kai Horstmann lifts the Anglo-Welsh Cup after a 28–11 victory over Bath at Kingsholm on 30 March, 2018. Jordan Mansfield/Getty Images

The brains trust: Rob Baxter is surrounded by his coaching team at Ashton Gate, 17 October, 2020. Phil Mingo/Pinnacle Photo Agency

From Teignmouth RFC to a crucial cog in the Chiefs’ pack, Sam Simmonds dynamic impact at No.8 saw him named European Player of the Year in 2020. Andy Styles (left) and Henry Browne/Getty Images (right)

The Maunder family celebrate with Sam after an England Under 20 match. From left to right: Jack, Felicity, Sam and Andy. Courtesy of the Maunder family

Olly Woodman soars over the line to score a remarkable try against Bath at Sandy Park in March 2020. Dan Mullan/Getty Images

The King of the North: Scotland captain Stuart Hogg in full cry for Exeter. Bob Bradford/CameraSport via Getty Images

Power play: the strength of the forwards is the heartbeat of the Exeter game plan – demonstrated perfectly by Harry Williams, who scored crucial tries in both the semi-final and final of the 2020 Champions Cup campaign. From five metres out, the Chiefs’ pack are virtually unstoppable. Dan Mullan/Getty Images

But there is grace allied to power as Henry Slade glides in to score a game-changing try in the 2020 Champions Cup final at Ashton Gate. Tom Jenkins

Master and Commander: 23-year-old captain, Joe Simmonds, roars in delight with Jack Yeandle after referee Nigel Owens finally signals full time in the Champions Cup final. Tom Jenkins

The ‘impossible’ dream comes true. Exeter Chiefs are crowned champions of Europe. Tom Jenkins

In howling wind and pouring rain, Jonny Gray steals a Wasps line-out on Exeter’s five-metre line in the Premiership final at Twickenham. Eighty metres later, captain Joe Simmonds bisects the Wasps’ uprights to secure a 19–13 victory for the Chiefs.Phil Mingo/Pinnacle Photo Agency

The Devon Double. Ten years after they clinched promotion from the Championship, Exeter complete the fairy tale by adding the 2019/20 Premiership trophy to their European Cup triumph. Phil Mingo/Pinnacle Photo Agency

For Fiona, Alex, Louisa and Greg.

And for Dad, who would have loved the Chiefs.

‘The roots run deep, in this rocky red ground

And I could feel that pull, every road I went down’

‘Growing Up Around Here’, Will Hoge

‘I begin to think there is something in the air of Devonshire

that grows clever fellows. I could name four or five, superior

to the product of any other county of England.’

Thomas Gainsborough, 1727–1788

PROLOGUE

The thwack of deflated rubber on damp tarmac is unmistakable. Oh no. Not now. Not tonight. At least there is space to pull over on a steep terraced street in Bristol but the bigger picture is a concern. Barring a laptop malfunction on deadline – imagine Edvard Munch’s The Scream with a set of posts in the background – being late for an important game is every sportswriter’s recurring dread.

What to do? Hidden in the recesses of the boot is one of those strange-looking space-saver tyres. There should be time later to replace the punctured original with this temporary, slim-fit alternative. Right now, though, the only option is to run the final mile and a half to the Memorial Ground, as people of a certain vintage still call it. Shouldering my heavy laptop bag, I set off down the hill, alternating between a stiff jog and a hobble. It’s a glamorous life, working in the media, until the ticking of the clock drowns out all else.

Luckily there is one seat left for a sweat-soaked, dishevelled latecomer in the tightly packed press box. Immediately to my right are some unfamiliar faces. A second glance suggests they are the visiting side’s coaching staff. This is no time, though, for idle chat. If Exeter Chiefs can defeat Bristol in this Championship play-off final second leg – they already hold a 9–6 lead from the first leg – and win promotion to English rugby’s top tier it will be the greatest achievement in the club’s 139-year history.

It also means that, by accident, the Telegraph’s Rob Wildman – otherwise known as ‘Borneo’ – and this correspondent have the best seats in the house. Thrashing away at my keyboard, praying for a readable first-edition piece to emerge, it strikes me how unnaturally calm the Exeter contingent seem. For the most part there is no great shouting or arm-waving. It is almost as if everything on the field is pre-programmed. When the head coach speaks – which is seldom – he is composed, precise and appears at least three phases ahead of the play. Out on the field his team look similarly well drilled. Where are the supposed nerve-riddled underdogs? With the weather worsening there is only one winner long before Simon Alcott’s last-minute try caps a 29–10 victory on the night. The Chiefs are going up.

On-the-whistle filing, sadly, allows scant time for leisurely reflection. There is the aggregate scoreline to get right, for a start, plus the small print – the teams, scorers, attendance etc. – and the headline facts. If Guardian readers want poetry they will have to find another newspaper. With a flurry of breathless adjectives safely sent, the next job is to squeeze out of the press box in the main stand and scuttle around the clubhouse to the distant media Portakabin where the post-match press conferences will be happening. If ever there was a night for gushing ‘We’re over the moon, Brian’ quotes, this is surely it.

Except they never come. The same tall, strong-jawed head coach who has largely kept his counsel during the game – aside from the occasional clench-fisted celebration towards the end – now speaks at length, without a trace of hyperbole, about his belief that this is just the start. ‘This hasn’t just happened overnight,’ he tells the anorak of reporters clustered around him. ‘We’ve been planning this for years.’ After he leaves, his audience are briefly silent. ‘Blimey,’ says someone eventually, ‘that Rob Baxter’s impressive, isn’t he?’

The slow crawl home offers an opportunity to mull over a few more things. The Kitson household has always looked west with affection. My father was raised in the Quantock Hills outside Taunton, his father lived and farmed on Dartmoor and there are strong Devon links on both sides of the family. Dad’s job as a land agent took him away to rural Hampshire but almost every family holiday involved a pilgrimage back down the A303 or A30. His timeless local sporting heroes – Harold Gimblett, Arthur Wellard and Bertie Buse – were similarly embedded in our consciousness, the County Ground in Taunton a spiritual home from home.

We did once buy Dad a Plymouth Argyle mug for Christmas but, otherwise, Exeter’s promotion was the biggest sporting success story in the West Country since the Somerset team of the late 1970s and 1980s started making Lord’s one-day finals. A generation of Wessex country boys imagined they could see something of themselves in apple-cheeked local heroes like Peter ‘Dasher’ Denning from Chewton Mendip, Frome’s Colin Dredge and Vic Marks from Middle Chinnock. Pride in those who make it big from small rural communities, on the rare occasions they leapfrog the city slickers, is among sport’s deepest and most genuinely heartfelt emotions.

Some of us felt similar romantic stirrings whenever Cornwall came good in rugby’s County Championship. The days of major touring teams being turned over down in Redruth’s Hellfire Corner, though, were long gone even before professionalism’s arrival. Despite the non-existence of elite-level football, Premiership rugby had never been sighted further west than Bristol. Good players – and there had always been plenty of those – with ambition had little option but to go and play elsewhere. No wonder Exeter’s elevation to the big league felt as refreshing as a cold cider on a warm day. By coincidence we were also due to be moving house to the Somerset/Devon border the following month, back down to the steep-sided country lanes and evocative red fields my fondly remembered dad loved so much. Someone, somewhere was smiling down benignly on us.

Good timing indeed. The seed sown that evening – Wednesday 26 May 2010 – has since become one of the best upwardly mobile stories in modern British team sport. Perhaps only Wimbledon’s ‘Crazy Gang’, Brian Clough’s European Cup-winning Nottingham Forest and Sir Alex Ferguson’s Aberdeen have risen as steeply from such humble beginnings. None of that round-ball triumvirate, though, sustained their success in the way Exeter are looking to do as they approach the club’s 150th anniversary year. Already the Chiefs have rewritten the accepted map of English club rugby and transformed how their region feels about itself. An everyday tale of county folk? Not remotely. The individuals who made it happen are an extraordinarily eclectic bunch: misfits, rejects, fishermen, farm boys, local lads, exiled Zimbabweans, Aussies and Celts, cider drinkers and cake lovers. This is their story, not mine.

ONE

ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST

Tucked into the low-slung, metal cattle shed otherwise known as the East Stand, it feels deceptively mild for the last weekend in December. Streaks of pale-blue sky are discernible and up on the horizon, above the corner flag diagonally across the pitch, is the hulking outline of Haldon Hill. Wintry, asset-stripped trees with grey, swaying halos peer over the top of the South Stand. To the right, beyond the David Lloyd fitness centre, is the Baker Bridge over the dual carriageway, named in memory of a long-serving council employee. It becomes an unofficial amusement park on match days, swaying and wobbling beneath the feet of the approaching patrons. For unwary newcomers it is a disconcerting welcome. It is an early sign that not everything at Sandy Park, the Chiefs’ hilltop lair, is entirely as it seems.

The distant far bottom corner of the north-east terrace is another educational vantage point. Among other things it offers a chance to appreciate fully the vast acreage of English rugby’s biggest in-goal areas. Not only could they accommodate a fair-sized flock of sheep but they lull first-timers into a false sense of security. Plenty of room down there, think the visiting playmakers – only to find a strengthening wind has mysteriously propelled the ball dead. Scrum back, Chiefs’ ball, have some more of that, my lovers. Entire chapters could be written on the vagaries of ‘Windy Park’: the swirls and hair-raising gusts, the deceitful calm spots. The Chiefs have lost the odd game on a ball’s capricious bounce but, over the years, local knowledge has won them loads more.

Today the mood is particularly thoughtful. Technically it is a 3 p.m. kick-off but there is a high-noon feel. Exeter v Saracens is that kind of fixture nowadays. The embattled gunslingers from the Big Smoke, heading out west to dish out some summary justice to the country boys; the narrow-eyed Chiefs on their porch fronts, silently watching them trot into town. Wayne Barnes is the referee but John Wayne would have been right at home. Every ticket was sold weeks ago. As Exeter take their usual deliberate jog in front of the East Stand ‘Library’ regulars before heading back down the tunnel, you can almost see tumbleweed blowing across the West Stand.

Victory over Saracens would settle a few scores, real and imagined. There is the Premiership salary cap saga, last season’s heartbreaking Cup final defeat, assorted personal rivalries and, last but not least, good old-fashioned bragging rights. The two clubs are not bosom buddies. The customary pre-match crunch of body on tackle pad has an extra urgency, the warm-up less about loosening muscles than preparing for a title bout. The director of rugby, Rob Baxter, stands on his own a few metres back, watching intently, as if auditioning to be the world’s sternest exam invigilator. Motivation is not going to be a problem today.

Because this date had been circled in Devon diaries for months, even before Saracens’ defrocking. Baxter stitches together a music-backed highlights package of every Chiefs victory to show his players prior to their next fixture but this week motivational speeches are superfluous. ‘I made a conscious effort not to say very much. Very early in the week, players were in meetings talking very emotively about the game. I was concerned about us mentally playing the game too early. I just talked very matter-of-factly. It was one of those games when I was at my most confident we’d be very good. The way the lads were talking, the things they said, their ambitions for the game. You could just feel it.’

Saracens, in festive red and featuring seven players involved in the World Cup final the previous month, also understand their champions’ aura is not as iron-clad as it once was. Their pre-match tally of -13 points and rock-bottom status in the table means they are now perceived differently, not least around here. Worse still, they have turned up on a day when local pride is practically dripping from the stands. Out of the tunnel emerge the familiar figures of Jack Nowell and Luke Cowan-Dickie, each celebrating his 100th appearance for the Chiefs. What an image it is: two rock-hard sons of Cornish trawlermen, blood brothers since the age of five, now among England’s finest. The stadium announcer, James Chubb, reckons the atmosphere is as charged as any he can recall in eight seasons of doing his job. Nowell is carrying his young daughter, Nori, in one of his ink-decorated arms. As the bloke next to me observes, she’s done well to have played a century of first-team games at her age.

Nowell, though, is determined to mark a special personal landmark for himself and his growing family. ‘Times like that don’t come around often. If I’m honest, during the warm-up, I was thinking about that moment more than the game. It’ll probably never happen again and I wanted to enjoy it for what it was. A packed-out Sandy Park, Nori in my arms and my best mate beside me. Running out to play for a club we signed for when we were 17. What made it even more special was the way the crowd reacted – and how the boys reacted as well. Nori enjoyed it until I gave her back to one of our conditioners. She took one look, thought, “I don’t know you,” and started crying. But when I show it to her in 12 years’ time she’ll say, “That’s cool.”’

By now the collective anticipation swirling around the record attendance of 13,593 is seriously intense. In many respects this unflashy place already has a different vibe to other grounds. Never, for instance, has the humble pasty been elevated to such lofty gastronomic heights. Not to be clutching one feels as culturally insensitive as walking into the Ritz and ordering a packet of pork scratchings. On an average match day here they sell almost 3,500 pasties and pour 35,000 pints; the all-time single day record for bar takings is £187,400. ‘My wife said that was just my bar bill,’ jokes Tony Rowe, the club chairman. There is also a hog-roast roll so vast and popular there was uproar when it (temporarily) disappeared from the media menu last season. No army marches on its stomachs quite like the ever-ravenous – and thirsty – press pack.

On top of everything else – and that is where he prefers it – is Derek the Otter. For a long time no home game was complete without a large furry otter chasing members of the public around the pitch at half-time accompanied by a Benny Hill soundtrack. Until recently, the man in the suit was an undercover officer with the National Crime Agency who spent the rest of his week busting drug dealers. Hurtling around in defiance of all health and safety directives and flattening patrons who just had to have it, ‘Derek’ soon became a cult figure. There were occasions, though, when even he came off second best, not least the day his previous occupant, Patrick McCaig, whose family run Otter Brewery, was tackled by a member of the Military Wives choir. Everyone laughed at the time – ‘My back’s never been the same since I was sat on by a Military Wife’ is a line rarely heard at Twickenham – but, eight years on, McCaig was still in sufficient pain to require an operation to fuse two of his vertebrae together.

Today’s first half is almost as punishing. Chiefs seize on a loose ball to register a kick-and-chase score for Nic White, as reassuringly irritating at scrum-half as ever, but make too many errors themselves. It allows Sarries some respite but Owen Farrell, unfortunately for him, is not privy to the secret of mastering the local wind conditions. Twice the England captain takes aim with kickable penalties and twice the ball fades stubbornly right when, theoretically, its flight should have been straight. Seven-nil at half-time does not sound much but, with the diminutive Joe Simmonds having held up the heftier Jamie George over the try-line just before the break, it feels like more from a psychological perspective.

Beneath dappled, darkening skies the third quarter is clearly going to be crucial. The last time Saracens were rendered scoreless turns out to have been 2010. There is no way they are going to drive home without firing a solitary shot. A gentle Otter-fuelled hum ripples around the ground, with some wondering aloud if Sarries have been on the Christmas sauce. Probably just the cranberry but they are looking distinctly mortal.

Local sympathy is not in plentiful supply. Exeter, in fact, are actively looking to wind their opponents up: Jonny Hill ruffles Will Skelton’s hair after Barnes spots a knock-on which prevents the big Australian lock from making some rare yardage. There is also a terrier’s snap to the home side’s tackling which Billy Vunipola is not appreciating. A skein of 17 geese fly high and purposefully over the West Stand, heading towards the Exe Estuary. Their formation is significantly tighter and more impressive than anything Sarries have yet managed.

Once the relentless South African flanker Jacques Vermeulen touches down beneath a pile of bodies to register Exeter’s second try, crisply converted again by the dead-eyed Simmonds, the visitors know there is no way back. Elliot Daly’s chip ahead rolls too far and Mako Vunipola needs lengthy treatment. The strains of the Tomahawk Chop, the hosts’ familiar battle cry, echo more loudly around the ground, reinforcing the slightly ghoulish feel. Appropriately, with darkness falling, on comes Ben Moon, one of the ‘Originals’ who have been around for every yard of the incredible journey from the Championship to the summit of the English game.

The lights are fast going out on Sarries: their quarterback Farrell is sacked behind the gain line, their forwards are being driven backwards. When White and Duncan Taylor tangle near the touchline, players from both sides rush in and a mass fracas takes place next to the advertising hoardings. The substituted Harry Williams, previously sin-binned, gets involved and is shown a red card from Barnes for his trouble.

Later, a different narrative emerges. The confrontation was significantly inflamed, according to the home players, by a comment directed at White by Billy Vunipola. In the view of England’s No. 8, Sarries had hoisted the silverware when it really mattered and this result changed little. Baxter still argues that the visitors were out of order: ‘When you see how disappointed our players have been and the things they’ve not had to celebrate and you then hear a Saracens player telling Nic White: “Unlucky, you haven’t got a Premiership winners’ medal,” that sticks in the craw. That’s what some of their lads were saying. They were rubbing in the fact they were quite happy to cheat to win titles. If people had experienced that, they would really understand what it has been like.’

Among Exeter’s players the widespread view is that Saracens have ‘a reputation of saying narky things when they lose’. Don Armand, the Chiefs’ outstanding Zimbabwean back-row forward, believes they have shown insufficient respect at times to him and his teammates. ‘It’s not necessarily their players’ fault but when they’ve won all those titles and been as gloaty as some of them have been . . . if you’ve been caught cheating and you know you’ve done it the wrong way and that cheating has helped you get those titles, surely you should have a bit of humility?’

On this midwinter occasion there is absolutely no argument about the better team. Saracens secure a consolation penalty try but, at 14–7 down, then kick the ball away rather than try and steal a last-gasp draw. Baxter is in no mood to spend the entire evening talking about Saracens but, eventually, delivers a blunt assessment to BBC Radio 5 Live: ‘There are supporters of rugby clubs who have watched coaches getting sacked and players leave and all different kinds of things. Part of that has been because of Saracens cheating.

‘You can’t run away from it. Sometimes the people who have pointed out that Saracens have cheated almost get painted as the bad guys. Well, the people who have made comment on it aren’t the cheats. And that is the bit some rugby supporters have felt frustrated about.’ Rowe, who has presided over Exeter’s ascent since taking over in 1998, has also been outspoken in his public criticism of Saracens. Baxter cannot understand why some have disapproved of him doing so. ‘I’ve seen some of the criticism of Tony and I don’t get it. What people don’t understand is that he feels for the players. That’s what really hurts him and that’s what really bothers me. When you live day to day with the players and see what they have been prepared to put in . . . I can see how some guys would use that as a really big motivation.’

That is precisely how Armand feels. He firmly believes the whole sorry saga will have the effect of propelling Exeter to greater heights. Even with Saracens removed from the frame, he also suspects the Chiefs’ agonising defeat in the 2019 final will, ultimately, prove a blessing in disguise. ‘In the next two to three years you’ll see the benefit. There are things that don’t need to be spoken about but will go forward as part of our psyche and our culture.

‘If we’d have won we wouldn’t have learned as much and wouldn’t have done as much to Saracens’ momentum as I think we did. Even though they won, it was one of those games when you know the opposition has really come at you physically and that the next time you play them it’s going to be tough.’ Hence the home side’s confidence on this last Sunday of the year. ‘Some of their players you just didn’t notice – and some of them were guys they’d normally rely on. I think it was a subconscious carry-over.’

Back outside in the evening gloaming, Cowan-Dickie, Nowell and full-back Stuart Hogg, swiftly settled into his new surroundings having swapped his native Scottish Borders for the small town of Ottery St Mary, embrace their loved ones and pose for selfies. Cowan-Dickie and Nowell have already had some photos taken in the dressing room, proudly standing with their fellow local hero, Gareth Steenson, who has just clocked up his 300th appearance in an Exeter jersey. As one Chiefs fan, Dave Church, tweets: ‘When they make the M5 embankment under the East Terrace into a Mount Rushmore-style sculpture, I’d imagine this is what three of the faces will look like.’ It is not the worst proposal for the side wall of the proposed new Sandy Park stadium hotel, the next part of the masterplan to secure Exeter’s finances for the long term.

Walking back to Digby & Sowton station car park – £4 in the charity bucket, beware the waist-high bollard halfway down the dimly lit lane – another thought occurs. At certain venues around the country it is possible to walk away from a club ground and wonder whether enough people truly care. Not at Sandy Park, not when Saracens have just been sent packing. If you yearn for old-school sporting fulfilment – and a decent pint – there are worse places to look for it.

* * * * *

It is another grey afternoon, almost 10 months later. Otherwise, much has changed. Normally 27,000 noisy supporters would be jammed inside Ashton Gate. Not any more, with fears of a second wave of Covid-19 infections on the way. The biggest occasion in the European club-rugby calendar, the Heineken Champions Cup final, is going ahead behind closed doors. It feels like a high-society wedding without any guests.

The tension, even so, is unbearable in every West Country living room. Just over an hour ago all was fine. Exeter had taken a 14–0 lead over France’s Racing 92 inside the first quarter, making the inconceivable look almost routine. Two close-range drives had produced a brace of converted tries for Luke Cowan-Dickie and Sam Simmonds and a disjointed Racing, beaten in two previous European finals, looked odds-on for a hat-trick. The Chiefs, having never previously advanced past the quarter-finals, were bossing the game.

Now the scoreboard reads 28–27 with just over five minutes left. Exeter have also been reduced to 14 men, their replacement prop Tomas Francis yellow-carded for what the referee Nigel Owens has been advised is a deliberate knock-on. It is only a reflex finger-tip graze of the ball but these days that merits 10 minutes in the sin-bin. ‘I don’t make the laws,’ says Owens, apologetically, as he explains his decision. No matter, Francis’s match is over.

In his absence, the Chiefs are under siege. They have already weathered 18 brutal phases close to their own line but how much more punishment can their bodies and minds withstand? Which is exactly what Antonie Claassen, whose father Wynand captained South Africa in the early 1980s, is thinking as he takes a flat pass from his scrum-half Maxime Machenaud five metres out and charges for the line. One slightly mistimed or weary tackle and the No. 8 will be over, destined to be feted in his adopted city of Paris for years to come.

Standing in harm’s way is Sam Skinner, another Exeter replacement facing the most pressurised moments of his sporting life. Now or never. The 25-year-old goes low and somehow stops his rampaging opponent six inches short. Just behind him the red-haired Jannes Kirsten, who like Claassen used to play for the Blue Bulls in Pretoria, dives in bravely and twists the Racing man’s upper body skywards as he drives for the line. With Claassen on his back, the ball is momentarily exposed. Sam Hidalgo-Clyne, Chiefs’ replacement scrum-half, spots the opportunity and clamps his body straight over the top. For the defending side, the peep of Owens’s whistle is the sweetest-possible sound. Penalty to Exeter, disaster averted.

At last the clock is the Chiefs’ friend. Another penalty following a line-out allows Henry Slade, scorer of his side’s vital fourth try, to swing a cultured left leg and punt his forwards even further up the touchline. Exeter can now attempt to dictate proceedings. A few close-quarter phases eat up further precious seconds but, as ever, a tiny miscalculation could still wreck everything. Entering the final minute Racing’s desire to force a turnover spills over and Owens spots another ruck offence 45 metres from the French line. Surely this must be it?

Instead, chaos ensues. Exeter seem uncertain whether or not to go for goal and Owens decides they are delaying too long. The referee orders an extra five seconds to be factored into the equation but when he asks for the clock to be restarted nothing happens. Ignoring the confusion, Exeter’s impressive young captain Joe Simmonds kicks the long-range penalty to widen his side’s advantage to 31–27. No one on the pitch seems entirely certain if the 80 minutes is officially up or whether the game should restart.

The world momentarily seems to have frozen like some mad H. M. Bateman cartoon. Is it possible that homely Exeter, just 10 years on from their Championship promotion in this same city, are about to become the champions of Europe? Can a team who were playing Havant, Aspatria, Walsall and Redruth in Courage League Division Four when the Heineken Cup was launched in 1995/96 really have conquered the ultimate club peak? Or is it all a cruel illusion, about to be shattered in one of the more extraordinary late twists of the modern era?

Owens, who has had an excellent game, is still frowning and talking. Gradually it seems a consensus is being reached. In theory the ball bisected the posts three seconds before the clock turned red. Because of the delay in re-setting it, however, the timekeeper instructs Owens that the game is officially over. Cue a lilac-and-purple haze of delirium. Devon is suddenly home to the best club team in Europe, the first side since the introduction of the English leagues to have hoisted every trophy from the fourth-division title upwards. The steepest ascent in British club history is complete.

In their moment of euphoria it is almost forgotten that the Chiefs still have a Premiership final to play the next Saturday. Even the absence of a crowd briefly ceases to matter, at least until players start pulling out mobile phones and making emotional calls to their families and loved ones at home. Up soars the trophy into the Bristol evening sky as Racing’s beaten players and coaches, gracious in defeat, stare on blankly. They are not the first to discover that the country boys of Exeter have hidden depths. As Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid used to mutter, while gazing down at the mysterious posse continually on their trail . . . ‘Who are those guys?’

TWO

GET ON, EXE!

Across the River Exe from the northern fringes of Devon’s cathedral city, it would be easy to miss the unpretentious farmhouse tucked away in a quiet valley off a narrow winding lane. The sun is making a timely reappearance after months of incessant rain and shafts of golden spring light flood in through the windows. It is bright enough for Bobbi Baxter to offer to draw the curtains to ensure her beloved husband, John, is not completely dazzled as he settles into his chair in the front room.

The enchanting Devon sunshine is what brought the Baxter family south from Lancashire in the first place. Even now John vividly recalls the day his life turned upside down. It was the late 1950s and the Baxters were looking to move from the village of Upholland, just outside Wigan, where the family had been well established for years. His father, Ted, had heard there was a small farm in the Lake District that might be worth a look. On the day the family visited, though, all they saw was rain. Gallons and gallons of it, cascading down from slate-grey, depressing northern skies. It was not the kind of weather to make the heart soar, let alone yearn for a fresh start in the saturated locality.

Sixty years on, every detail of what happened next remains sharp. The following week Baxter senior received details of another property, 250 miles away in Devon. When the family headed south to check it out it was as if Walt Disney himself had choreographed the backdrop. The sky was cornflower blue, the birds were singing, the hedgerows were alive with wild flowers and the Lake District felt like a different universe. It would have taken a heart of granite to resist so much bucolic charm and the Baxters were instantly bowled over.

What if it had rained instead? There is every chance the whole extraordinary Chiefs story might not have unfolded. Even at the time it cannot have been a straightforward decision. The family roots in Upholland ran particularly deep. Locals still refer to Baxter’s Pit, once a prominent mine in the West Lancashire coalfield, while other members of the extended Baxter clan ran the local grocery store and butcher’s shop. In 1929 the Wigan Observer’s report on the golden wedding of a Mr & Mrs Baxter of Brooklands House offered some insight into the extended family genes. ‘They were married at St Peter’s Swinton on Oct 29, 1879 and have had ten sons and three daughters . . . all ten sons were over 6ft in height, the tallest being about 6ft 4¼ in.’

Ted Baxter and his wife, Annie, were never going to rear shy, retiring kids. John’s brother, Paul, was named Alexander Paul Baxter after Alexander the Great. For John they chose the first name William, after William the Conqueror. Young W J Baxter, however, was less interested in great historical characters than rugby league. Wigan were the mightiest force in the land and his absolute favourite was Billy Boston. One day, walking across the car park towards the boys’ enclosure at Central Park, he spotted Boston ahead of him. Unable to contain himself, he rushed up and tapped the latter on the shoulder. Far from being irritated, Billy turned around and rewarded his besotted young fan with a smile wider than the Pennines. John knew in that split second what he wanted to do in life: to emulate his hero and play for Wigan himself.

Instead, aged 15, he was uprooted to a place where rugby league was an entirely alien concept. At school in Crediton it was union all the way. It was also swiftly apparent that the newcomer with the northern accent was a more than useful player. At the local town club the senior players took him under their wing and dropped him back home to the family farm after games. Playing-wise, he went on a couple of tours to the Midlands, rubbing shoulders with English internationals who, to his eyes, were nothing special. Back home, people started to whisper in his ear. ‘John, come and join us . . . you’ll get your county and international cap if you come to Exeter.’

It was unquestionably a club with proud traditions. Founded in 1871, the same year as the Rugby Football Union, Exeter had been around longer than allegedly more distinguished sides like Gloucester, Bristol, Leicester and Northampton. Another attraction for the abrasive young forward was the chance to play with Dick Manley, one of the rare breed of Exeter players to have caught the eyes of the faraway England selectors. It said it all, though, that even the well-regarded Manley, a cabinet maker, was a month short of his 31st birthday when he was finally capped at flanker against Wales at a straw-strewn Cardiff Arms Park in the long, freezing winter of 1963. Exeter was seen as a distant backwater and the club struggled to gain fixtures with the top London sides, with travel not easy in the years before the M5 opened fully in 1977. Baxter senior remembers the interminable coach trips well. ‘To get to anywhere in the early 1960s was very difficult. We used to kick off every season with Moseley away. Trying to get up there for a 3 p.m. kick-off around the holiday period, before the M5, was impossible. We were as good as anybody; it was just geography. Us, Bristol, Bath, Gloucester . . . we were all on a par.’

As well as good, hard local players, there was also a ready supply of talented student teachers from St Luke’s College. Among them were distinguished future England players and coaches such as Don Rutherford and Mike Davis, both of whom helped to raise standards. Importantly, too, there was Bob Staddon, originally from Ilfracombe in north Devon, who would become one of Exeter’s most loyal servants.

A talented all-round sportsman – he also opened the batting for Devon – Staddon had been quietly thrilled to arrive at St Luke’s to discover his personal tutor was Martin Underwood, who won five caps on the wing for England in the early 1960s. One Friday night in October 1964, Underwood had been due to play against Bristol at the Memorial Ground but was forced to cry off. The inexperienced Staddon was taken aback to receive a phone call inviting him to make his first-team debut. He was even more surprised to be asked to play at centre, a position he had never previously occupied. The opposition were more than handy – the erstwhile England captain Richard Sharp was at fly-half with Roger Hosen at full-back – and Staddon’s first taste of senior rugby involved having his hand trodden on by Bristol’s Jimmy Glover, whose daughter Helen Glover would strike Olympic rowing gold half a century later. Exeter, despite everything, lost only 19–16 and the youthful Staddon was warmly welcomed into the fold. More than half a century of selfless service later, he is the club’s president.

When it came to no-nonsense forward play, Exeter could also be relied upon to supply a certain – how to phrase this – physical vigour. Baxter could always be found in the vanguard. ‘It was physical in a different way. The scrum was totally different. It was a genuine competition. Front rows would not go down because they knew if they did they’d get the hell kicked out of them.’ Staddon recalls some particularly lively exchanges with Plymouth Albion, and not just on the field. ‘We played one game there in the early 1970s when the referee stopped the game and asked for the club secretary to come out of the stand and have old man Baxter removed from the ground. The secretary was too afraid to do it.’

Nor was John Baxter the kind of opponent with whom to take liberties. ‘John was the enforcer in our team. He had a reputation and it was richly deserved. There was a famous Cup final in Torquay when there was an incident involving me. I wasn’t the bravest of rugby players but John took exception. In front of the referee he came up to the prop in question, who was a chef, and gave him a haymaker. We thought he’d be sent off but the ref just said, “Don’t do that again.” John was a hard, physical player and a very good one.’

He was also not renowned for communicating in flowery rhyming couplets. Staddon’s former teammate, great friend and Shaldon neighbour, John Lockyer, had moved up to play for Exeter from his local club Teignmouth in 1969/70 when it was just becoming de rigueur for hookers to throw in. Lockyer, who also captained Exeter and remains a passionate summariser on BBC Radio Devon – ‘I think we’ve got ’em now, Nigel!’ – was understandably keen to keep his line-out jumpers happy.

‘How do you want it, John? Quick and flat?’

‘Just chuck the fucking thing in. I’ll catch it.’

It was not unknown, either, for the occasional unidentified clenched fist to emerge from the second row if a member of the opposition took too many liberties, although Exeter’s front-rowers argued they accidentally copped the majority of them. There were plenty of other characters in the squad, not least Paul Baxter who, when it came to team photographs, liked to roll his sleeves up to emphasise how big his forearms were. It was also the latter who, as captain in the club’s centenary season of 1972/73, decided it was time for Exeter to abandon the amateur tradition of the team being picked by committee men in smoke-filled rooms. ‘Right,’ he said, looking around the room at the old boys all puffing on their pipes. ‘From now on, as captain, I’m going to be chairman of selectors.’

Other pivotal figures included Andy Cole, a Cullompton farmer who narrowly missed out on a Cambridge blue. He could play prop as well as back row and captained the club for four years. His teammates reckoned he was the hardest, fairest player around, not to mention the strongest. Witnesses still talk about the day he arrived to help Staddon move house and picked up the chest freezer all by himself. Cole also had the whitest boot laces of anyone in the West Country, courtesy of his mother who boiled them clean after every match.

Even before you laced up a pair of boots, playing rugby for Exeter also required serious commitment from a geographical point of view. Staddon, for instance, soon grew familiar with every twist and turn of the A35 on his way from Bridport, where he was teaching, to attend training on Tuesday and Thursday nights and play at the weekends. Away fixtures were an even bigger undertaking in those pre-motorway days. When playing, say, Bridgend in South Wales, Exeter would leave home at 6 a.m. and travel up to Gloucester before winding their way slowly back down through the valleys. Clubs like Leicester would head on tour to Devon at Easter but not every leading club fancied getting dragged into the mire at the reliably wet, clay-based County Ground. As Staddon put it: ‘Teams didn’t like to come to the County Ground. It was invariably a very difficult place to play rugby.’

Even touring Springbok sides found life awkward in the Devonshire mud, while Exeter’s rising profile was increasingly reflected in the make-up of the Devon side which was prospering in the County Championship. Perennial high-fliers Gloucestershire were beaten at Torquay, with eight Devon players selected in a combined Devon and Cornwall XV to face the All Blacks at Redruth in January 1973. Lockyer featured at hooker alongside the renowned Cornish stalwart Stack Stevens and John’s brother Paul Baxter with the 18-year-old John Scott at lock, although local rugby politics – and a partisan local printing firm – meant only the Cornish-based players had their full biographies printed in the match programme.

Circumstances, though, frustrated John Baxter’s ambitions to win a full Test cap. He was picked to play in an England trial but the timing was unfortunate. ‘I hadn’t played for six weeks beforehand because I’d twisted my knee. “Sod it,” I thought, “at least I’ll get a decent meal.”’ He finished on the losing side but the invitation was a vindication of sorts. He was ‘carded’ for an England summer tour but, as with Manley a few years earlier, felt obliged to decline the invitation. ‘I couldn’t go because I couldn’t bloody afford it. That was the end of it.’

He also had to stop turning out for Exeter in 1973, aged just 27. ‘I’d suffered some hearing problems and I was going deaf. Money was tight and I just couldn’t afford to carry on playing. I had too many other responsibilities. You try milking cows on a frosty morning when you’re injured. Trying to put the cups on with freezing fingers when you’ve just played a big game the previous day. It wasn’t Mickey Mouse rugby, it was proper stuff. If I couldn’t get into the club I’d train on the farm in the evenings, carrying a sack of potatoes around. I used to keep weights in the barn. Whether I was ever fit I don’t know but I always thought I was pretty strong. Rugby was a release, a pleasure; a chance to get away from it all and let off steam. I like to think I gave as good as I got.’

By now, John was also a family man. One fateful evening he and a mate had driven up from Morchard Road to Barnstaple to attend a dance at the Wrey Arms. From her vantage point across the room, Bobbi instantly decided she liked the look of the tall, muscular stranger. Coincidentally she had also moved down from the north-west as a young girl and settled with her parents in Braunton. The shared connection was immediate and, before too long, they were married. Four children – two girls and two boys – followed as the family moved between various farms. Joanne arrived first, followed by her brother Robert, who was born in Tavistock Maternity Hospital on 10 March 1971.

Both he and the couple’s third child, Richard, were chips off the solid old Baxter block. Soon enough the two young boys were running around behind the posts at the County Ground, collecting balls and helping out with the ground’s old-fashioned scoreboard on match days. They did their best but, all too often, a vital number or a crucial supporting pin would be missing. Spectators had little option but to fill in the blanks mentally until the next score materialised.

No one seemed to mind too much, not least because the team were winning regularly. Throughout the mid-1970s they enjoyed consistent success, particularly when they beat the mighty Bristol and, to their rivals’ consternation, qualified ahead of them for the national John Player Cup. In January 1978 they were drawn at home to Bath, with England’s John Horton at fly-half, in the first round of the Cup and won, convincingly, by 20–6.

In rugby, though, success is tough to sustain. By the early 1980s, many of Exeter’s stalwarts were growing older and the lack of a formal recruitment strategy was starting to tell. Results began to nosedive: between 1983 and 1985 Exeter were beaten by, among others, Crediton, Sidmouth, Devon and Cornwall Police and Tiverton. To make matters worse, their old rivals Plymouth were growing stronger. All concerned could feel the balance of power shifting. ‘We got a bit arrogant,’ acknowledges Staddon. ‘You could almost hear other clubs muttering, “That’ll teach you, Exeter.” People were not exactly broken-hearted.’

* * * * *

Illustrious Devon sportspeople were also a lesser-spotted breed. A case could arguably be made for the Tavistock-born Sir Francis Drake, although details are hazy as to whether he actually did continue playing bowls on Plymouth Hoe as the Spanish Armada approached in 1588. Alternatively, step forward Sir Walter Raleigh, born in East Budleigh, who sailed similarly far and wide and introduced multiple generations of British athletes to the concept of the relieving pre-match fag.

Twentieth-century contenders in team ball games are even harder to find. Perhaps the outstanding individual was the Exeter-born Dick Pym, Bolton’s flat-capped goalkeeper in three victorious FA Cup finals in the 1920s, during which he conceded not a single goal. Pym was very much his own man, famously deciding to return with a parrot from an Exeter club tour to Brazil. When the parrot died it was buried beneath one of the goalmouths, only to be exhumed after supporters started to fret about the Grecians’ lack of goals at that end. Within days of the old bird being dug up, the goals began to flow again. Pym, who won three caps for England, hailed from a fishing family and, after retiring from football, returned to spend his latter days catching fish on the Exe Estuary at his native Topsham.

The Plymouth-born Trevor Francis also represented his country but never played first-team football for the Argyle. Neither Plymouth nor Exeter City have ever featured in the top tier of league football despite being founded in, respectively, 1886 and 1904. Otherwise, apart from Sir Francis Chichester (the son of a north Devon clergyman and the first yachtsman to circumnavigate the world single-handed), Tom Daley, Sharron Davies, Jo Pavey and Sue Barker, the ranks of non-equine world-beating performers from England’s third-biggest county have been relatively few.

It is a curious phenomenon given that Devon – with its plentiful fresh air and wide open spaces – has all the makings of a sporting hotspot. There are surfers and sailors everywhere and – viruses permitting – the granite uplands of Dartmoor are covered in teenagers competing in the annual Ten Tors hiking challenge. Cyclists, jump jockeys, golfers, cricketers and open water swimmers jostle for recognition as well.

First among equals, though, remains rugby, as synonymous with the south-west peninsula of England as the cream tea. It has ever been thus. They were playing a version of the game at Blundell’s School in Tiverton in 1868, Exeter played their first official match in October 1873 and, following the reorganisation of the English County Championship in 1896, Devon emerged as one of the country’s strongest teams. They won the title in 1899, finished runners-up in 1900 and then either won or shared the title in five of the next 12 years.

The most frequently recited story from that time, however, involved a defeat so big some simply could not believe it. Within a week of Dave Gallaher’s 1905 All Blacks arriving in Plymouth by boat, they faced Devon at the County Ground in Exeter on 16 September. When the final score was phoned through to a London agency it read ‘Devon 4 New Zealand 55’. Convinced it must be a mistake, a sceptical sub-editor reversed the result to read ‘Devon 55 New Zealand 4’. A long-running debate also rumbles as to how, exactly, the first recorded reference to the ‘All Blacks’ appeared in the paper. While the touring team’s kit was black, some claimed it was actually a spelling error and referred to the ease with which every visiting player ran and passed the ball. As one breathless newspaper correspondent wrote, they were ‘all backs’.

In an effort to establish the truth, the respected Kiwi sportswriter, Ron Palenski, dug his way back into the archives and came across the following post-match reference in the local Express & Echo: ‘The All Blacks, as they are styled by reason of their sable and unrelieved costume, were under the guidance of their captain (Mr Gallaher) and their fine physiques favourably impressed the spectators.’ What no one disputed was that Devon’s finest came a distant second, prompting Lord Baden-Powell, of subsequent boy scout fame, to suggest England’s youth were in decline and comprised ‘thousands of young men, pale, narrow-chested, hunched-up, miserable specimens smoking endless cigarettes’.

For the next century and more the south-west generated few national sporting headlines. Yeovil’s sloping pitch did briefly capture the public imagination following a 1949 FA Cup giant-killing win over Sunderland, while Argyle memorably reached the FA Cup semi-final at Villa Park in 1984. The sight of Trelawny’s Army pouring up to Twickenham in 1991 to watch Cornwall win the County Championship final and claim their first title since 1908 was similarly evocative. To more youthful observers, though, there was an analogue feel to much of it. Celebrating the Wurzels, Jethro and the Beast of Bodmin Moor is all very well but, eventually, you need something more in your locker. If ever there was a sporting region desperately seeking a fresh hero or two it was the slow-paced, success-starved south-west.

THREE

TAKE ME HOME, COUNTRY ROADS

A new era, of sorts, was starting to dawn in English rugby. The game was still officially amateur, of course, but on the field Bath were setting fresh standards under the canny Jack Rowell. Jeremy Guscott, Stuart Barnes, Richard Hill, Jon Hall, Gareth Chilcott and Graham Dawe were a collective cut above: there was only one champion team in the West Country and it wasn’t Exeter. In 1982/83, to underline the point, the latter endured their worst season playing-wise since 1957/58, losing to Sidmouth, Barnstaple, High Wycombe, Tiverton, Camborne and Devon & Cornwall Police. When they ventured up to the Rec it was not even a contest, Bath setting a new points record in a painfully one-sided 74–3 victory.

It was hardly a surprise, then, when the first official merit tables were drawn up and Exeter did not feature among the country’s top 24 sides. Only in the following 1985/86 season were they included in the imaginatively named Merit Table C alongside Nuneaton, Roundhay, Morley and Metropolitan Police. They were fortunate still to be involved in the third tier when the Courage National Leagues – consisting of three divisions of 12 with sides playing each other only once – were finally launched in 1987/88. Even faithful club servants like John Lockyer could not ignore reality. ‘Had the leagues been formed a year earlier we might have gone. We were that poor.’