5,85 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: STORGY Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

From Trumpocalypse to Brexit Britain, brick by brick the walls are closing in. But don’t despair. Bulldoze the borders. Conquer freedom not fear. EXIT EARTH explores all life – past, present, or future – on, or off – this beautiful, yet fragile, world of ours. Final embraces beneath a sky of flames. Tears of joy aboard a sinking ship. Laughter in a lonely land. Dystopian or utopian, realist or fantasy, horror or sci-fi, EXIT EARTH is yours to conquer.

EXIT EARTH includes the short fiction of all fourteen finalists from the STORGY EXIT EARTH Short Story Competition, as judged by critically acclaimed author Diane Cook (Man vs. Nature). EXIT EARTH EXTRA contains additional stories by award winning authors M R Cary (The Girl With All The Gifts), Toby Litt (Corpsing), James Miller (Lost Boys), Courttia Newland (A Book of Blues), and David James Poissant (The Heaven of Animals), in addition to stories by Tomek Dzido, Ross Jeffery, Alice Kouzmenko, Tabitha Potts, and Anthony Self. With exclusive artwork by Amie Dearlove, HarlotVonCharlotte, CrapPanther, and cover design by Rob Pearce.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 548

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

EXIT EARTH

Duncan Abel

Virginia Ballesty

Erik Bergstrom

Michael Bird

Jessica Bonder

M R Carey

Rachel Connor

Tomek Dzido

Francisco Gonzalez

Philip Webb Gregg

Robin Griffiths

Ross Jeffery

Alice Kouzmenko

Richard Lee-Graham

Toby Litt

Tomas Marcantonio

James Miller

Courttia Newland

David James Poissant

Tabitha Potts

Alan Robson

Anthony Self

Guy Smith

Paul Turner

Copyright © 2017 by STORGY®

All rights reserved

STORGY.COM

First Published in Great Britain in 2017

by STORGY Books

Copyright © STORGY Ltd 2017

STORGY

LONDON

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the express permission of the publisher.

Published by STORGY Ltd

London, United Kingdom, 2017

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

eBook ISBN 978 1 9998907 1 1

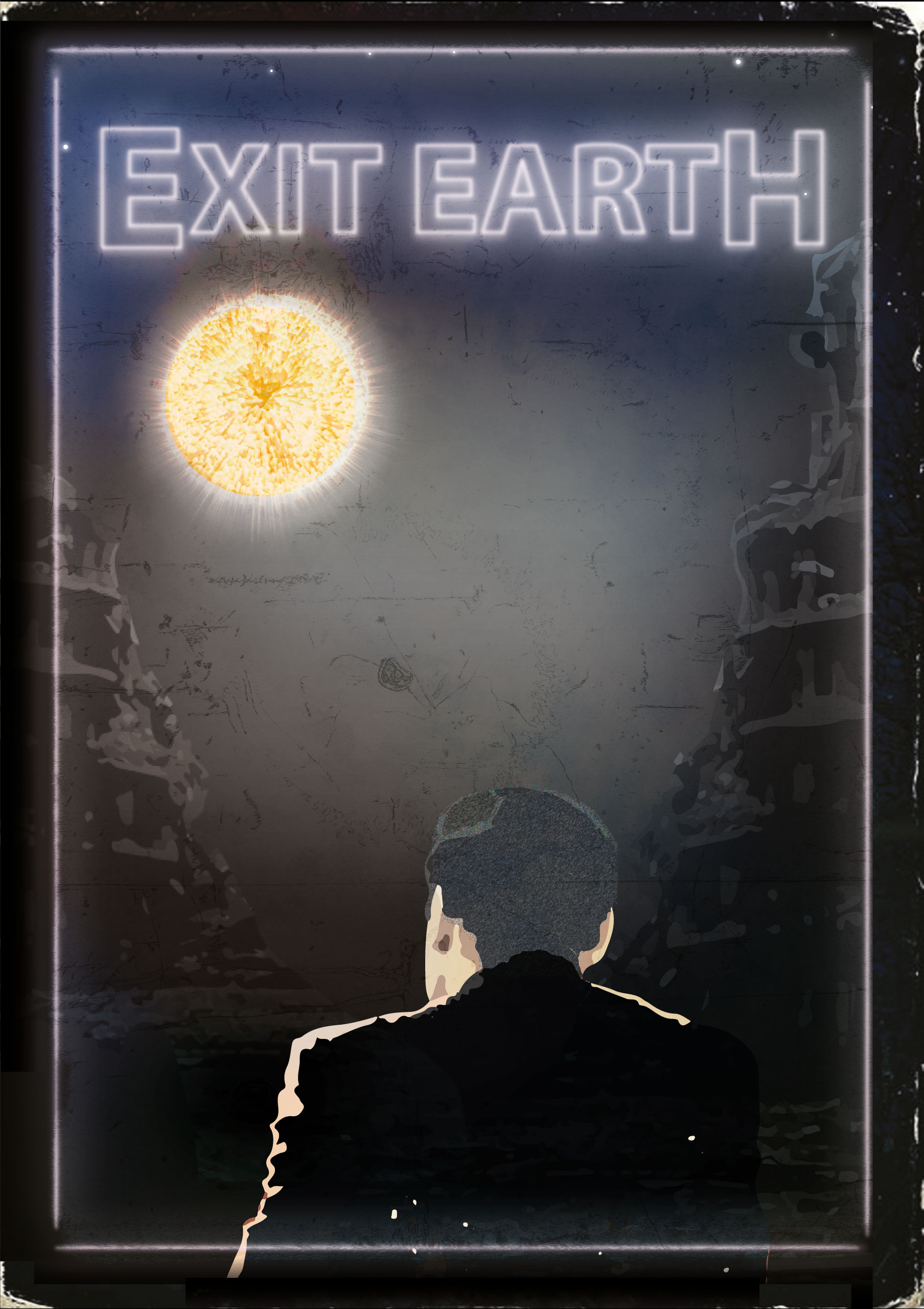

Cover design by Rob Pearce

Contents

Foreword

HOW TO CURATE A LIFE

Rachel Connor

Afterword

DON’T GO TO THE FLEA CIRCUS

Duncan Abel

Afterword

WHEN THE TIDE COMES IN

Joseph Sale

Afterword

CROW RIDES A PALE HORSE

Erik Bergstrom

Afterword

SONGS THAT ONLY SQUIRRELS CAN HEAR

Francisco González

THE SUPERHERO

Tomas Marcantonio

Afterword

THE EUTH OF TODAY

Richard Lee-Graham

Afterword

CAKE

Virginia Ballesty

Afterword

FALLOUT

Michael Bird

Afterword

KEN

Jessica Bonder

Afterword

AND THE WAVES TAKE THE WORDS

Philip Webb Gregg

Afterword

EARTH 1.O

Robin Griffiths

Afterword

RECORDED INTERVIEW 3

Guy Smith

Afterword

NO STATE

Paul Turner

Afterword

EXIT EARTH EXTRA

THE SONS OF TAMMANY

M. R. CAREY

THE FANGLUR AND THE TWOOF

TOBY LITT

SIX MONTH ANNIVERSARY

JAMES MILLER

DARK MATTERS

COURTTIA NEWLAND

THE BIRDS, THE BEES

DAVID JAMES POISSANT

ARTICLE ELECT

TOMEK DZIDO

DAYLIGHT BREAKS THROUGH

ROSS JEFFERY

RED

ALICE KOUZMENKO

THE RECKONING

TABITHA POTTS

BIRTHDAY TREAT

ANTHONY SELF

INTERVIEWS

Interview with Duncan Abel

Interview with Joseph Sale

ILLUSTRATORS

COVER DESIGN

JUDGE PROFILE

Interview with Diane Cook

Acknowledgments

DEDICATIONS

Also Available From

STORGY MAGAZINE

“What the caterpillar calls the end of the world, the master calls a butterfly.”

- Richard Bach -

Foreword

So, here we are. The EXIT EARTH Anthology. We made it.

Some of you may have read our previous anthologies, or the short stories we publish on our website, or experienced the work of our artists, and may even know a little about who we are and what do. For those of you who haven’t, and for whom this is your first STORGY BOOK, welcome.

I feel no greater urge than to express our immense gratitude to an array of talented and dedicated people with whom we have worked on EXIT EARTH. Whilst it is most common to give thanks as the finale of a book, this is our beginning, and we begin with thanks and praise.

Thank you to everyone who has ever submitted their writing for our consideration, whether it was selected for publication or not. Each and every story we have read has enriched our lives and taught us lessons beyond the craft. Thank you to everyone who has read the short stories we publish and visited our website. Your continued encouragement and support is truly treasured.

Thank you to all our regular writers and reviewers who continue to offer their words for our - and your - consumption. The list is long, but each of you has enabled us to keep the faith. We would not exist were it not for your commitment to our cause. Your contributions have been - and will hopefully remain - invaluable to us and all our readers. You have helped to keep the dream alive.

Thank you to all the artists who have worked with us on EXIT EARTH and all our previous e-books; HarlotVonCharlotte, Amie Dearlove, CrapPanther, Rob Pearce, and Henry Davis. Your phenomenal artwork never fails to enhance the quality of our books and working with each of you has been an immense privilege.

Thank you to all the writers contained within this anthology; Rachel Connor, Duncan Abel, Joseph Sale, Erik Bergstrom, Francisco González, Tomas Marcantonio, Richard Lee-Graham, Virginia Ballesty, Michael Bird, Jessica Bonder, Philip Webb Gregg, Robin Griffiths, Guy Smith, Paul Turner, M. R. Carey, Toby Litt, James Miller, Courttia Newland, and David James Poissant. This book would not exist without your amazing words.

Special thanks to Diane Cook for judging The EXIT EARTH Short Story Competition and for helping us choose the stories you will soon discover.

Thank you to everyone who pledged their hard-earned money to our Kickstarter campaign. Publishing a print book has long been a dream of ours and each of you helped to make it finally come true. What you now hold in your hands is a product of your passion and faith in STORGY and all our authors and artists. You have enabled us to print EXIT EARTH and enter the publishing world, a world in which we plan to stay.

Thank you to the incredible team at STORGY. Alice and Tabitha you have both enlightened me with your endless enthusiasm and determination. Without your hard work we could not have published EXIT EARTH. I feel blessed to have met you, friends.

Lastly, thank you to Anthony Self and Ross Jeffery. From the very beginning of EXIT EARTH you have never wavered in your commitment and dedication. STORGY would not exist in all its forms were it not for your fervent belief in everything that we are and aim to be. I will never forget this unbelievable journey. Thank you for making it fun.

Finally, thank you to all our family and friends and thank you to you for buying this book. The only thing we ask is that if you enjoy EXIT EARTH, tell others about it. Encourage them to buy a copy, or give yours away. Take photos of the book or the stories or artwork contained within and share them on social media; #exitearth. We hope you enjoy it as much as we have.

Right, that’s it from me.

No back-story or bullshit.

This is EXIT EARTH

...welcome...

Tomek Dzido

HOW TO CURATE A LIFE

by Rachel Connor

It has taken a week to harvest the girl’s life. Jesse’s device is connected to hers by a flex that curls across his desk like an umbilical cord. She was haphazard in her digital existence. Over six months of life-log footage, none of it edited. All that’s left of her now, though, is powder; food for some memorial bush. The anachronism of a freshly-dug bed in winter. The garden of her parents’ house, suburban, detached, red brick. He remembers, as they sat in the kitchen, the father’s rolled-up shirt sleeves, his tanned forearms. The easy way he slid the notes across the chestnut counter.

Jesse couldn’t remember the last time he’d seen real cash. It was stacked in piles, centimetres from his bag. It would have been easy to scoop it up and leave, bargain struck. The urge to touch it was strong. No wonder transfers were the sanctioned means of exchange. Less messy that way, no coins or paper rubbing against fabric, or flesh.

‘They’ll want to know where it came from.’

‘They won’t ask,’ the father said. ‘Not at my bank.’

The wife, opposite, with her indolent eyelids. The warm spiced smell, churning out from the vent: cloves and cinnamon. It made him think of a distant December. Hands around a mug, feeling the heat spread across his palms and his mother’s face, eyes closed, satiated by the moment.

‘More than a hundred times its electronic value.’ The father caught his eye.

Jesse would become a man with capital; the owner of a box held deep in the innards of a building. He’d heard about those who visited their bank just to touch it. He imagined the texture of ink against his fingers, the pattern in relief of some long-dead monarch.

‘I don’t have the authority,’ Jesse said. ‘Not without a will. Your daughter’s digital estate — it still belongs to her.’

‘We’re her parents.’ The mother’s voice was stretched tight like a rubber band. ‘Surely we have a say?’

‘Legally she was an adult. There’s no loophole. I can’t just —.’ He looked at the father.

‘We hoped you’d consider it. Discreetly of course.’ The mother nodded at the money.

Jesse had only once pressed delete. He didn’t know if he was ready to do it again. He looked at the sister. She didn’t want this, he was sure. ‘If your daughter had come to me —’. He opened the laptop. ‘Look, I can still collate her data.’ He clicked open the tab and angled it towards them.

‘Why don’t you take a look at the designs?’

‘If she were alive, we wouldn’t need you.’

At the mother’s words, there was an intake of breath from the sister. She turned sharply away. He saw, through the window, a bird table in the centre of the lawn. The ground was strewn with rotting leaves.

The mother sat forward, back ramrod straight. ‘Have you ever lost anyone?’

‘My parents,’ Jesse said. ‘Both of them.’ He realised they were waiting for more. There was silence and a blast of warm air from the room conditioner as they sat staring at each other: the sister, the mother, the father, and him.

‘Then you’ll know. You’ll know what it’s like. You’re online and her face pops up. Photos you didn’t know existed, maybe even one you’ve taken.’ She looked at him. She was in the hard phase of grief, he could see, the angry part. The echo in Jesse’s ears, the words he wanted to say. That once it is done, there’s no going back.

A movement across the partition makes him look up: Sal sliding from one end of her desk to the other, the sound of casters on the hard floor. She initiates a FaceTime and he hears her caffeinated laugh, thinks of the freckles in that dip below her throat. Some days, when it’s hot, he sees the sheen of sweat on her skin, a suppressed urge to taste it again. That last time on her kitchen floor. He’d had a sense, even as she opened the door, that she was going to end it. But that word — passive — jabs at him even now.

‘You plan on taking a break this month?’

Django’s voice behind him, at the entrance to his booth. It’s almost violent, being wrested away from the world he’s been populating, the world of the dead girl. Footage of summer days, light cutting across the lens, the fizz of orange and yellow at the periphery of vision. Insta images. Haystacks in a field, perfectly spaced.

‘Lunch?’ Django sticks out his thumb and motions to the door, a hitch-hiker in an old movie.

Jesse opens the drawer to retrieve his cards, turns to the window to assess the day. Bright winter sunshine. He pockets his sunglasses. They walk down the corridor together, Jesse trying to match Django’s pace. He follows him down a flight of stairs to the ground floor until they push through the automatic doors and into the light.

It’s just about mild enough to sit in the quad, the central square of green that is subdivided by wooden decking and bamboo grass. They pick up soba takeaway from one of the coloured trucks parked at the entrance. A runner in a fluorescent vest laps the perimeter, tracking his progress on a watch.

‘So.’ Django’s mouth is full of noodles, sauce dripping onto his chin. ‘The file you’re working on. Want to tell me about it?’

Jesse is aware of the knot of office girls sitting nearby. They’ve brought those thin, plastic-backed travel rugs with them. Even wearing coats and cardigans, they stretch out their legs to catch the sun. One of them has her eyes closed. He wonders if she is listening.

Jesse nods towards them. ‘Best not.’ He tastes tofu and peppers, a sharp hit of chilli. ‘Anyway — you know the pact. It’s lunch.’

Django turns to look at him. Wide open eyes, fringed with black lashes. Jesse sees why women go crazy for him. ‘I checked the drive. You haven’t set up a template.’

He feels a prickling at the back of his neck, that cold clamminess he’s experienced before. A flash of his father’s dying face. The rasping breath. The hand on top of the sheet that everyone expected Jesse to hold. But he couldn’t bring himself to do it.

He focuses on the action of his chopsticks. He needs to be careful, even with Django. ‘The parents haven’t come back on the design yet.’

Django leans into him. ‘They made you a deal, didn’t they?’

Raucous laughter erupts from the office girls. One holds her hands over her mouth and the others are ribbing her about something.

‘In your job, it’s always going to happen. It did to Rasmus. Remember him?’

‘The Danish guy?

Django nods. ‘The client’s husband was cheating on her. When he died, she got Rasmus to —.’ He makes a cutting gesture across the throat. Jesse checks to see if the office girls are watching.

‘He made a will, though, right?’ Jesse whispers. ‘The husband?’

Django shakes his head.

The runner has stopped, stands with hands on hips, face contorted.

‘How do you know this stuff?’

‘I keep my eyes on the drive. You start to see the patterns.’ Django takes a swig of water and offers the bottle but Jesse thinks of the black bean sauce residue, shakes his head. Django looks back at him. ‘I don’t see what’s taking you so long.’

The office girls are on their feet, shaking out their rugs, collecting the remains of their lunch. Django darts a look at them, then turns to Jesse.

‘If you’re going to delete everything,’ he hisses, ‘why bother to collate it?’

There’d been very little of his father. A few scanned-in photos with a thick white border, taken in his sporting days. Rows of young men with long hair and green jerseys, those at the front squatting. His father in the middle, the grinning and victorious captain, the ball by his feet. When Jesse hit delete, he erased the photograph. But he couldn’t forget the smile.

Django reads something in his face and his laugh reveals disbelief, frustration. ‘You haven’t decided.’

‘I’ve got ’til the end of the week.’ Jesse can’t tell his friend that he hears the dead girl breathing. He knows her. ‘I just think — ’ The runner is lying on the ground, legs vertical, stretching his hamstrings. ‘They might change their minds.’

‘You’re insane. You know that?’ Django gathers up their detritus — the empty cartons, drink bottles — signaling the end of lunch. The way he dumps it in the canister makes Jesse’s irritation rise.

By Friday afternoon, he’s gone through everything but the video content. She preferred Polaroid Swing, so her YouTube is minimal. In the first film, she’s in a park; a dot moving amongst the trees, so far off that he wonders if it’s her at all. A face comes into the frame. A boy. Downy hair on his cheekbones catching the light. He is smiling, confident in the knowledge that, even across the distance, he has her in his grasp. Jesse can trace the boy’s movements, the sensation of grass under bare feet. Then the screen goes dead. What happened? Did the boyfriend grab her? Did they collapse on a blanket, his hands on her hot skin?

Jesse clicks on the Polaroid folder. He hadn’t watched them when he was collating, just used the still of the first image as an index. There are so many images of her at parties, gardens in the dark, fairy lights strung in the background; girls wearing too much make up. He hovers over the icon, risks being pulled in to the memories of places she’s been. Travels around Europe; festivals. It’s not so long since he was doing the same, and he remembers the American backpacker in Prague. The hostel’s musty sheets. The way the ends of her hair felt against his chest and thighs.

The file has somehow opened. Jesse’s fingers are on the mouse. A still of the girl’s face: dead but very much alive. She’s laughing, pulling back a strand of blonde hair. It must be hot because she is wearing very little. There is the whisper, underneath her shirt, of a bikini; cornflower blue. It brings out the colour of her eyes. She is looking at him. He activates Swing and the image becomes real; a woman’s body moving in time and space, the hand settling the hair back into place. She turns away but, over her shoulder, her smile, broadening.

Jesse is mesmerised. He’s there, on the sand dunes; the prickle of marram grass against his legs, gritty sand in his mouth. She is soft. The heat of her midriff under the shirt. He closes his eyes as she hoists herself on top of him, because he knows what will happen next. She will touch him. He will grow hard. Hidden in the hollow of the dune, the heat on their backs; he’ll feel her breasts brush against him. He will enter her gently and she will be wet, making it easy to work inside her.

He feels overheated, pushes back his seat. In her cubicle, Sal is staring at her screen, earbuds jammed in. Across the way, Django grins. In the toilets, Jesse closes his eyes but can’t prevent the images replaying. He splashes his face with water and looks at himself in the mirror. How is it possible to feel desire for a dead girl? He can’t believe she isn’t here, laughing, dancing, having sex. He swears he can feel her mouth on his neck.

He leans over the basin, breath into his lungs: the biological function that keeps him alive. It stopped, suddenly, for her. He never asked how she died. There are photos of her grinning from a kayak, helmeted, paddle in hand. He imagines her slipping under the surface, her foot catching on a reed or a piece of metal on the riverbed, toiling and fighting to break free and finally relenting, everything slowing down. The last thing she would see: her boyfriend’s face.

Jesse looks at the scar under his left eyelid; the stubble on his chin. Signs of the body being alive, trying to heal itself. He turns the tap on again, washes his hands. He remembers the first time his father took him to visit his mother in hospital, the chemical smell, her tight smile, welts across her wrists: her only means of escape. Only later did he realise how persistent she must have been.

Back at his desk, Jesse puts his headphones on and selects a soundtrack. Deep Focus. He’ll need it for what he’s about to do.

By the time he’s finished, everyone has gone. As he leaves the office, the sensor lights activate and the corridor twitches into life. He feels, momentarily, like an actor on stage. The muscles in his legs ache from the strain of clenching them at his desk. He longs for the rhythm of the tram and a few minutes’ sleep before he’s spewed out of the station and onto the streets.

At reception, the reflections in the windows make it difficult to see where the outside begins. Starkey is in his usual seat, head down, staring at a tablet. Jesse recognizes the porn site. His dick twitches, involuntarily. He thinks of her.

Starkey closes the cover of his tablet. ‘A late one for you.’

Jesse nods, hands over his staff ID and Starkey files it away with the others.

‘No devices tonight?’

Jesse smiles. ‘Giving myself the weekend off.’

He pushes his bag through the X-ray scanner and pictures what the machine won’t pick up: a piece of paper. A handwritten letter that he’ll deliver to the girl’s parents tomorrow.

Jesse wants to be outside, to feel the evening cold against his skin. The revolving door is slower than usual and he waves as he goes through: see you next week. There’s no need for Starkey to know. He’ll find out soon enough when the email reaches Jesse’s boss on Monday with news of a job elsewhere. He wonders, briefly, if Sal will miss him.

The bag is so light. The girl no longer exists. But what he’s done is much more creative: a new template, a record of her life. He has managed her online presence, locked it away so no one can retrieve it. No one — not even her parents — will know she’s there. The data is encrypted. She’s indelible, anyway, for him; stored in that part of his brain he vaguely remembers from his ancient science class. The limbic region. The hippocampus.

Jesse thinks about tomorrow, how he’ll sleep until late, watch movies in bed and eat takeaway from the carton. At some point, he’ll cross the threshold to run along the river, altering his route to take in the suburbs. The sun will set slowly. He’ll breathe as he runs, inhaling water vapour, the girl’s molecules; her biological traces.

1st PRIZE

HOW TO CURATE A LIFE

by Rachel Connor

Rachel Connor is a novelist, dramatist and short story writer based in Yorkshire, where she teaches creative writing at Leeds Beckett University. In addition to writing plays for stage and site-specific performance, she has published short fiction and is the author of a novel, Sisterwives. Her debut radio drama The Cloistered Soul was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2015 as part of their Original British Dramatists season. She is currently exploring how technology can facilitate powerful experiences of immersive

storytelling.

Rachel is on Twitter @rachel_novelist

Afterword

There is something fascinating about imagining a future we cannot yet see or know, just as we might reconstruct a past that is out of our reach. ‘How to curate a life’ began as an idea from something I found online about careers that will be ubiquitous in the future. It is predicted that, some day, there will be a job for people overseeing the digital estate of a person after death: a digital death manager. This prompted so many questions. When we die, who owns the self in virtual form — the deceased person, or the next of kin? Are we ever truly dead if there are traces of the self in images and our exchanges online? And where, in all this, is the soul? Once the body has expired, is our online footprint a repository of the soul, a means of achieving immortality?

Of course, there are no answers. Being human is a mystery that has puzzled us for millennia and will surely continue to, whatever era or cultural context we exist in. ‘How to curate a life’ is my attempt to explore the fundamental needs we have, as humans, to connect, to touch and be touched, physically and emotionally; to matter.

And, there’s the thing. We are matter: simply collections of atoms, cells and stardust. But the human condition can also contain, if we allow it, the feeling of something bigger; something that is both burden and gift. Our connection to other beings makes us, in the end, weightier than bodies, more powerful than the constellations of energies clustered in the stars.

DON’T GO TO THE FLEA CIRCUS

by Duncan Abel

We were dying of hunger. Uncle Horatio had been the first to go. I wanted to draw him as he lay there, cold and bone-thin in just his underpants. Mumma wouldn’t let me. She said we had to bury him before the Circus came for his body. But that was yesterday.

This morning, in the kitchen, Grandpa was ripping the tongues out of my school shoes.

‘There’s nutrients in the leather,’ he said. ‘Did you know that, Ely?’

‘They’re my only pair, Grandpa.’

He continued hacking at them with his penknife.

I looked past him, through the frayed curtains to the snow-covered street below. People just walked past the bodies that lay on the pavements now. There were too many to bury. No one had the strength.

I took what was left of my shoes from Grandpa and sat on the cold linoleum to pull them on.

The front door clicked and Mumma came in, the bottom of her coat wet from the snow.

‘How’s the broth?’ she said.

‘It’s getting there,’ Grandpa said, ‘Hey, Ely?’

‘Yes, Grandpa.’

He dropped the shoes’ tongues into the pot, along with a tangle of leather belts, which really we needed because our trousers had all grown too big.

‘I managed to get this piece of carrot and a sachet of sugar,’ Mumma said.

She was shivering beneath her coat, tensing her shoulders as if to hold her bones together.

‘Drop ’em in the saucepan, then,’ Grandpa said. ‘We’ll eat today. Like kings, we’ll eat.’

I side-stepped to the door, hoping neither of them would notice.

‘Where are you going, Ely?’

I looked back to him, to both of them. There was a feeling these days that the last time you saw someone, it might be the last time for good. I did a mental sketch. They were both a mismatch of skin, bone and ragged clothing. I suppose I was too.

‘I’m going for a walk,’ I said.

I could see Mumma weighing up whether to say it or not. Grandpa spoke for her. He was serious now. Moral.

‘Don’t you go to the Flea Circus.’

Outside, people moved slowly and silently. Oversized coats drooped over their curved spines and dragged in the snow. There were fewer people each time I came outside, and those left had grown so pale they were almost transparent. I kept my eye out for the men from the Circus. But I didn’t really know what they looked like. I only knew the rumours.

Across the street from our tenement, I saw Mr Henry coming out of his house; he used to be my art teacher before the Big Starve. His suit hung from his bones as if he were a scarecrow made of broom-handles and old coat hangers. He still wore the flower on his lapel.

‘Good God, Ely. It’s wonderful to see you alive,’ he said, the creases in his face turning almost to a smile. ‘Where are you going?’

I found the strength to shrug.

‘Are you still drawing?’ he asked.

‘Doesn’t seem much point if we’re all going to die.’

‘We were all going to die anyway, Ely. You must draw what you see. Leave something so people will learn about all of this.’

He cast his hand out at the streets. It made me see it all anew. Ransacked buildings. Looted shops. Decayed limbs poking out of the snow. Up on the hill, you could see the high fences the government erected to keep us in – or was it to keep us out? I couldn’t see any of the border-guards patrolling them, though. But they were there. We knew that.

‘How’s your family?’ he asked, and then lowered his voice, ‘I heard you had all…’

‘Mumma and Grandpa are still alive,’ I said. ‘And I’m still here. How have you been managing, sir?’

He took too long to answer, and I could see it in his eyes.

‘You haven’t been going to the Flea Circus, have you, sir?’

‘These are difficult times, Ely.’

I thought of Mumma and Grandpa – what they would say if they knew what I was thinking? But these days I mostly thought with my stomach. I whispered, as if to prevent my own conscience from overhearing.

‘Will you take me with you?’

‘The Circus, Ely. It’s not a place for children. Not anymore. I bet you don’t even have any money, do you?’

I put my hands in my pockets, my fingers prospecting for any coins I might have forgotten about. All I could feel was my leg. Bony. And cold.

‘I have this watch.’

‘No one’s keeping time, here, Ely.’

‘But what’s the point in money?’ I said. ‘You can’t eat it, and there’s nowhere to spend it.’

But something in what I said seemed to snag his ear. His yellowy eyes searched for whatever secrets he thought my own eyes might be hiding. But there were no secrets here anymore. Women had stopped dyeing the grey out of their hair, stopped shaving their legs. And the men, once proud and private, had become beggars on street corners. Hunger had made us equals. Starved out our hidden truths the way a poacher smokes a rabbit out of its warren. Mr Henry held his stare.

‘You don’t know about the Bottleneck?’

‘Is it a way out of here?’ I said, but he didn’t answer, just began walking down the street, my footprints in the snow a pace or two behind his.

In the doorway of what used to be the library, two men in long, grey coats were loading a stretcher with the frozen corpse of a young woman. A blue-lipped smile frozen to her face. She almost looked happy. They stopped when they realised I was watching, and met me with a stare that remained unbroken, even when a swirl of wind flecked their beards and eyebrows with snow.

Mr Henry pulled my shoulder. ‘Come on, Ely,’ he said, his eyes remaining on the men in grey coats. An understanding between them to which I was not privy.

‘Are they from the Flea Circus?’ I said, glancing back. They were still watching me. ‘Are they the men from the Circus, Mr Henry?’

‘Look, if you’re coming with me, please, Ely, don’t ask questions.’

The Flea Circus used to be an old flourmill before the river that ran through here grew to a trickle and then to a puddle and then to nothing at all. The wheels and gears of the grain mill were rusted together and the wooden structure had rotted to a sagging skeleton, but the stone structure remained mostly intact.

Candlelight wobbled as Mr Henry and I stepped inside; the shadows took a moment to settle back into the sunken eyes of the men and women who hunched in silence. The place reminded me of the opium dens I once read about in Victorian stories of London, Bangkok and Burma. In the corner, a lady was quietly shushing a baby, the tired hint of a lullaby on her breath. She pulled from her cardigans a breast, floppy and empty. She put it to the child’s lips and tried to wring out the last drips of milk. No one spoke. Mr Henry patted the seat next to him.

Before The Starve, Jonah and I used to go to the Flea Circus after school. We’d save our lunch money to buy the Madame’s honeycomb and chocolate covered raisins. Some people said she used dead flies instead of raisins, but I could never tell. She would wind up an ancient pipe organ and, on the millstone-stage, command her fleas to perform their tricks. They would walk across a tight rope, score goals with tiny footballs, pull chariots through a maze. Once, I saw a flea pedalling a tiny Penny-farthing. I had once tried painting what I had witnessed at the Flea Circus, but I always found it difficult to draw from memory, and Mumma never liked those paintings. She said there was something sinister in the fleas that scared her. Mr Henry said he liked the way I pulled a darkness out of primary colours. I gave one of my paintings to the Madame once, hoping she would display it in the auditorium. I never saw it again.

A dust sheet lay over the pipe organ now, silence the only accompaniment.

Soon, a curtain swung open, and the Madame entered.

‘I thought your family was too good for us,’ she said.

I went to speak, but she didn’t care for it.

‘Everyone ends up at the Flea Circus one way or another,’ she said. ‘Did anyone follow you?’

‘It’s just me and Ely, here,’ Mr Henry said.

‘How much have you got?’

Mr Henry held out his hand to show her a few coins. She sighed.

‘Is it for both of you?’

‘Ely’s starving, Madame.’

‘Everyone’s starving,’ she said, and pocketed the money before disappearing behind the curtain. Mr Henry and I sat together on a small bench that was church pew cold. I couldn’t stop myself from looking at him. Funny how teachers looked so different out of school. He was almost like a real person. Sad. And tired. His eyes stayed forwards, and his nerves made me nervous.

The Madame returned with two steaming bowls of soup.

‘Are you sure no one followed you? Not the police? None of those border-guards…’

‘Quite sure, Madame,’ Mr Henry said.

She handed us the bowls and pulled two spoons from her apron. The lady who was nursing the baby looked up, but when our eyes met, we both looked away.

I balanced the bowl on my knees and stared into the soup. When I brought a spoonful to my lips, a thought of Mumma made me hesitate.

‘Don’t deny yourself, Ely,’ said Mr Henry. ‘We have no choice.’

But it was as if he were convincing himself as much as anyone else – his conscience made easier by spreading the immorality out among us all. There was no going back.

I had heard people say that human flesh tastes like chicken, but in the weak, thin soup it tasted of nothing at all. No sooner had we begun eating, it was nearly all gone. I slowed to make it last. Not just the food, but the damp warmth of the Flea Circus. The heat from the pot-stove. I could feel my body coming back to life as if it had been a deciduous tree, clenched against winter. Mr Henry stood to leave. The Madame appeared from behind her curtain.

‘See you again,’ she said.

I had never been inside Mr Henry’s house, even though we were friends long before The Starve. He had always let me stay after school to use the art equipment, while he marked students’ papers or planned his lessons. My friends said it was weird that I wanted to spend time with him. Grandpa said it was weird that he wanted to spend time with me. I just thought he was friendly. Mumma said he was lonely.

His house was a jumble of bric-a-brac, and the damp air made the dust stick thickly to everything. The walls were covered with paintings.

‘Did you paint these, sir?’

He hesitated. The look on his face was one I hadn’t seen before. Embarrassment, I think.

‘Just that one,’ he said.

I positioned myself in front of the painting. Maybe even tilted my head. The colours were such an intense mix of greys and dirty whites that, at first, I thought it was a just a pattern, some expression of monotony or disillusionment. But a closer look revealed figures, people so faded that they were almost invisible within the heavy brushstrokes. It was very ugly, and I didn’t know how to compliment him on it.

‘Can I see more of your paintings?’

He didn’t answer, just lit the fire and set a brass kettle over it. He dropped some nettle leaves in two mugs and added the water when the kettle boiled.

‘Let it absorb the nettles’ nutrients for a minute,’ he said.

I held the cup in my hands the way Mumma did when she was trying to warm herself. Mr Henry sat in a high-backed chair and spread a blanket over his legs. I stood with my back to the fire, the warmth crawling up my spine. It became so hot that it burned, but I wanted to somehow store the heat in my bones for later.

‘You won’t tell my mumma that I’ve been to the Flea Circus, sir?’

He sipped his nettle water. I copied. It was nice. I wondered about asking Mr Henry if I could take some nettles home for Grandpa’s next batch of broth.

‘How on earth is she sustaining you all, your mumma?’ he said.

‘Grandpa survived the last starve,’ I said. ‘He finds calories in all sorts of things.’

‘I don’t know how they’ve managed to keep such a tight grip on their morals. God knows, Ely, I tried not to go to the Flea Circus. I resisted for so long, but hunger – it’s a kind of madness, isn’t it?’

I thought of Grandpa, eating postage stamps because he said there was nutritional value in the glue.

‘I thought I’d go, just the once,’ Mr Henry said, ‘just to get my head clear so I could make some kind of plan. But once you cross that line... God knows, I’ve sat next to people down there, Ely, people I’ve known all my life. They don’t acknowledge you. They don’t even look up. No one wants to admit to being there. Even to themselves.’

‘Grandpa said it’s illegal, what the Madame does down there?’

‘Of course. But I’ve seen police officers eating with the rest of us. The laws we make are only ever as robust as those who enforce them. No law will stop us trying to survive.’

Mr Henry swirled the nettle leaves in his mug and slurped.

‘Have you ever wondered, sir, how long it will be before there’s just one person left, having eaten everybody else? Just one huge person surrounded by bones and old clothes.’

He thought for a moment, his hands together like a steeple. ‘Perhaps that’s the subject of your next painting. Here, have some more water.’

‘What’s the Bottleneck, sir?’

He added a few nettle leaves to my cup.

‘A secret is what it is.’

‘But what is it, actually?’

Mr Henry’s smile sagged in defeat.

‘There’s a bridge. You know where the river used to bottleneck through the woods.’

‘But the army fenced right around behind those woods. I went there on my bike when everyone was making a run for it.’

‘Some of the guards who work that section, they smuggle one or two people out every night. Sold to the highest bidder.’

‘So why have you not bought your passage, sir? You have money, don’t you?’

‘I’ve tried. God knows I’ve tried. I’m outbid every time by one of the Madame’s family, and the days when the bids are low, I’ve been so mad with hunger that I’ve spent my money at the Flea Circus. We all inch closer to death as the Madame and her family, one by one, find their way out.’

We fell quiet then. A renewed futility crept in. If survival was bound to wealth, there was no hope for Mumma and Grandpa and me. We had sold anything of value, and we’d even begun burning our furniture for warmth. We were the ones for whom the fences were built, that was clear.

Days passed. And then weeks. Each morning I made an excuse to go to

Mr Henry’s house. I told Mumma that we were drawing, and that he was showing me his paintings. I’d take my sketch pad and brushes, but each day we’d go to the Flea Circus.

Back at Mr Henry’s house, we did draw. Even though the energy used was a cost. He worked on a sculpture using dried twigs. He said they looked like bones and was the only medium he wanted to work in. I began composing sketches for my picture, ‘The Last Survivor’. We worked together in a busy silence. We enjoyed each other’s company. Treated each other as equals. His sculpture began to take life. A contorted human being, knee deep in bones. My composition was ready to transfer to canvas. But there was no end to The Starve.

Rumours that aid was on its way were met with counter-rumours. We stopped believing anything. We had been abandoned. That was all there was. It was each for his or herself. Each town for itself. Each country for itself. Grandpa grew weak, but it was Mumma who died first. I hadn’t realised that whatever morsels and rations she had, she had been giving to Grandpa and me. The world was growing silent.

Once Grandpa died, I stayed at Mr Henry’s. In time, we noticed that the portions at the Flea Circus had grown smaller. The dead were so skinny that even human meat grew sparse. The men in grey coats were waiting on people to die. Stalking us. We couldn’t go on like this. The end was near. I could see it in Mr Henry’s eyes, hear it in his dusty cough. He knew he was on his way, and maybe that meant that I was too.

He looked peaceful in his chair, the morning I found him, his head resting on his shoulder. The room had a different smell. Quietly, as if he might wake up and catch me, I looked through his belongings. His own paintings were hung on his bedroom wall. Mostly nudes of a young man. For a moment, I thought it was me, but most of them had been painted before I was born. I missed him even more for knowing this about him.

I was on my own. And yet, I still believed that things would change. I’d lost everything, but still wanted to survive.

The Bottleneck was my only hope. I ransacked Mr Henry’s drawers, looking for anything of value – a few coins, bits of old jewellery. Each night, I went up to the bridge to watch the bidding, pleading, and the greed. The bids fluctuated over the days, growing too high and then crashing. I had collected coins from wherever I could but money was of increasingly low value. The global markets had crumbled. Currencies were failing. People wanted tangible items like food, clothes, medicine. The true value of gold and silver had been revealed – it was just metal. I broke into unoccupied houses and grabbed tablets, tools, matches – items of intrinsic value.

My rucksack was filled with everything I thought valuable, but I was growing weaker and had to fight myself from trading it all in down at the

Flea Circus. Just hold on, I told myself, the bids were decreasing; I would soon be there.

The night for me to travel had come. It was now or never, I could feel it. But the hunger. I couldn’t control it. If I just spent a few pennies at the Flea Circus. Just a…

I wrapped myself up like an Arctic explorer. It was so cold, each step through the snow heavier than the last. I was so weak that my vision blurred, but I was close… so close… the Flea Circus… a small piece of food, just to get me to the bridge, and then…

I don’t know when I fell, but there I was. I hadn’t the strength to stand and, like someone drowning, I lost all sense of up, down, left, right. Was this really it? The end. The spot where I would die. I knew of hypothermia and the insidious way in which it gives the impression of warmth, tricking you into giving up the fight. So, I fought to stay awake. Wait for someone to see me. But my eyes… my eyes kept…

I didn’t know how much time had passed, but I could feel someone moving me. Was I really still alive? I could see the blurry grey shape of two men. I tried to speak, but my voice was numbed by the cold. I put every remaining scrap of strength into swallowing, trying to clear a passage for my words. My eyes were too weak to open, but in the cold blackness I heard my voice, as if in a dream. ‘Please, please… Take me to the Flea Circus?’

The bag zipped up over my head. And a strange warmth.

‘Yes, Ely,’ said one of the grey coats. ‘We’re taking you to the Flea Circus.’

2nd PRIZE

DON’T GO TO THE FLEA CIRCUS

by Duncan Abel

Duncan Abel’s short stories have been published by Unbound Press and Spilling Ink. His short story, “A Good Son”, was performed at London Lit 2012. His novel, The Way Home, was shortlisted for the 2010 Luke Bitmead Award. Duncan Abel has written for BBC Radio drama; his Afternoon Play, When I Lost You (co-written with Rachel Wagstaff), was broadcast in 2013. His monologue (also co-written with Rachel Wagstaff) based on the life of Isambard Kingdom Brunel was performed and recorded by Hugh Bonneville, for Sing London. For the stage, Duncan Abel is currently under commission to The Original Theatre Company and Marion Theatrical Productions.

Afterword

I’ve always been struck by the fact that we live in a world where a great number of the population is dying from starvation, while a similarly great number is dying from over-eating. “Don’t go to the Flea Circus” came from the concept of mass starvation. I took some inspiration from accounts of those who had survived the Leningrad Blockade, the Blockade of Germany and from survivors of shipwrecks, and the lengths to which they went in order to stay alive: cooking their shoes, licking the glue from envelopes and, in the end, eating human meat.

With this story’s post-apocalyptic vision, I felt that an unspecified time, place and ‘event’ would allow the reader to project and recognise aspects of their own town, their own country, and not consider it to be a story about a problem faced by “other” people but, rather, a potential problem faced by us all.

WHEN THE TIDE COMES IN

by Joseph Sale

We knew exactly when it was going to happen because they told us, so we went down to Nauru Coast to watch the sunrise.

We set out at 3:00am and clambered down the dust-slick cliffs, using palm trees as handholds. We found our usual perch, an old World War II bunker, the red sun flag scrubbed off through erosion and buried under layers of crude graffiti.

Hidetaka brought two crates of Asahi and a cooler. We swigged it like westerners, watching the darkness in silence. The sky was moonless and starless, deeper dark touching the rippling mirror of the ocean. Ayako wore a short white skirt of all things; it shone like a luminous, giant lily. I imagined the goosebumps on her legs from the cold. Her hair shone that kind of purple-black, making her shoulders look like they were draped with a mantle of night itself.

After a while, Hidetaka broke the spell.

‘If you could have sex with one person right now, who would it be?’

Ayako didn’t hesitate.

‘Solid Snake.’

‘What?’

‘He’s fictional,’ I reminded her.

‘So? There weren’t any rules about that.’

‘Okay, explain your reasoning,’ Hidetaka grinned like a talk-show host. He had hair that looked like a mop and was always falling in his face. His teeth were slightly yellow from all the sugary sweets he loved. From a distance, I imagined he’d look something like a scarecrow – all gangly limbs, clothes dangling from a wire frame. I guess all three of us must look like scarecrows. There was no one else around.

‘He has a perfect body,’ Ayako started, putting a finger to her lips playfully. She could be a model, a magazine cover-girl, a stripper, a superstar, anything with those looks, but she is just the world’s most-tipped hotel receptionist.

‘The best that computers could render in 2008.’ Hidetaka nodded.

‘And it’s that gravelly voice too. David Hayter’s so sexy.’

David Hayter was the American-born actor living in Japan who voiced Solid Snake in the Metal Gear Solid video-game series for 20 years. Ayako is an avid gamer. Another reason most men go crazy over her.

‘You prefer him to the Japanese guy?’ Hidetaka was incredulous.

‘Definitely. Something about him. I think Kiefer Sutherland made a good Snake too. But nowhere near as good as David Hayter. I think there’s something boyish about his voice which makes him cute. You know. He’s all rugged but also like a child. It pushes all the buttons.’

Hidetaka stuck out his lower lip and nodded.

‘Okay, Ryu, what about you?’

In my head I said: Ayako, Ayako, Ayako and only Ayako.

Out loud, I said:

‘Natalie Dormer.’

‘You’re both traitors!’ Hidetaka cried, throwing his hands in the air. ‘Bloody westerners taking the hearts of our best and brightest.’

‘But isn’t she really old?’ Ayako said, raising an eyebrow.

‘She’s thirty-five.’

‘Ancient!’

‘Ayako’s right. She’s too old for you, Ryu.’

‘She doesn’t look it though, does she?’

‘Well...’ The expression in Ayako’s eyes was hard to read in the dark.

‘You see, my theory is, Natalie Dormer is one of those people whose beauty comes down to bone structure. Therefore, she’s not really going to age. She’s just going to mature into her looks. I guess the same way men do.’

‘It’s true, old men are hot.’ Ayako nodded fervently.

‘So in choosing Natalie Dormer I play the long game,’ I concluded, raising a beer. ‘To Margaery of House Tyrell!’

Ayako laughed. The sound was like sea foam rushing up my body, the cold a secret, balmy blessing. Hidetaka chinked his beer bottle next to mine, downed it, and threw it out onto the beach. It hit the sand with a dull thud.

‘Hidetaka!’ Ayako shouted. ‘The environment!’ She pointed a stern finger and narrowed her eyes.

We all froze for a moment, then burst out laughing.

‘Come on Hidetaka, you tell us yours now.’

Hidetaka put his chin in his hand, doing his best impression of Socrates pondering some weighty question about reality.

‘Hmm, hmm, hmm, this needs some thought.’

‘Come on!’ Ayako poked him in the ribs. He yelped and swatted her hands away. She tickled him, digging her fingers beneath his armpits. Hidetaka squealed and rolled around, batting her hands away as though they were hornets. I watched, drinking, wishing I could have such easy physical contact with her. Ayako never starts this kind of thing with me. I wonder if it’s because she knows I couldn’t handle it, that I would think it meant something more.

‘Okay, okay, it would have to be Lucy Liu!’

Ayako opened her mouth in shock.

‘You’re a traitor too?’

‘At least she’s Asian!’

Ayako crossed her arms and turned away from Hidetaka.

‘Unacceptable.’

She winked at me and giggled. My heart attempted to beat regularly, but ended up cascading, like a fall of blossoms, shed all at once.

‘So the truths are out,’ Hidetaka exclaimed. ‘That’s all. That’s all I wanted.’

We laughed, finished our drinks, got new ones, then settled into silence again. I checked my watch. It was 4:00am. The cold deepened to stinging point. There was still time.

‘What happens when the tide comes in?’ Ayako stared out at the water. There were grey rock formations a few hundred meters out that looked like gravestones, casting sundial shadows over the waters. I wasn’t sure what she was asking, what she could possibly mean. I’m not even sure she knew what she is asking, just talking to fill the void.

‘I guess all the tourists just pack their bags and leave,’ Hidetaka said.

I nodded in agreement.

‘High tide puts the whole beach under, right up to the treeline.’

We shared contemplative silence again.

‘You ever been skinny dipping?’ I couldn’t believe the words spilling from my mouth, but then, things were different now we knew.

‘What’s skinny dipping?’

‘Sounds western.’ Hidetaka couldn’t hide his suspicion.

‘It’s when you swim naked in the sea.’

‘You crazyman!’ Ayako grinned, her teeth eerily like the Cheshire cat’s, two frightening sickles. I wondered if she’d had whitening. ‘I’m cold enough already. Don’t need to get any colder.’

‘It won’t be cold once you get swimming.’ I lied. ‘Besides, the sea is always two months behind the weather. It should be ok now.’

‘Who told you that?’ Hidetaka looked a little bit like The Rock, his eyebrows at mathematically impossible angles.

‘Natalie Dormer.’

They both laughed. Laughter can be like a drug. You get addicted to hearing it, until you want it after everything you say.

‘So how about it?’ I stood up, gesticulating wildly and shouting about the wonders of skinny dipping, half of it made up and the other half incomprehensible; I felt like I’d never felt before, some kind of religious leader with ideology and purpose. The reality was just some drunk trying to get his friends to run butt-naked into the sea with him.

‘Okay, okay! If you won’t shut up about it!’ Hidetaka stood up and threw his beer into the sand (a little pile of brown beer bottles had formed at this point). He ripped off his T-shirt, exposing a body entirely without musculature or fat.

Seeing his bare chest made me realise it was real, and a terrified shiver ran through me. I remember studying abroad in England for 3 years and going to London, seeing St Paul’s Cathedral for the first time, standing beneath the magnificence of that art, its colossal, dwarfing architecture like something from the realm of the shinigami, striking down those unworthy to look upon it. No wonder, I’d thought, westerners walk with a hunch when they have to live beneath such terrible structures. I was filled with awe but also fear. I understood, I thought, their God, and heaven and hell, and righteousness, as I stared at the gold-plated Christ, writhing in agony amidst this helical, Gothic wonder. The shadows of that place were deep, but the light, incredible. I felt so nervous then, as if I might be crushed any minute by sheer awe. Buddhism has nothing like that. There is awe, yes, to stand beneath the Emerald Buddha, but Faceless Compassion does not carry with it the destructive omnipotence of their holy, tortured God.

Hidetaka whipped off his belt, dropped his pants, showing thick black tights.

I burst out laughing.

‘It’s cold!’ he exclaimed. ‘It’s cold, alright? So I wore tights.’

Ayako pushed him and he tumbled from the bunker, falling into the sand with a squawk. She stood, pulled off her top like there was nothing in the world to be afraid of. I had to fight not to stare, so tackled my own T-shirt, but I could barely get it over my head, I was sweating so profusely, fingers weak.

I felt her hands on mine. She yanked and the T-shirt came loose. We stood face to face. I don’t know what my eyes showed, but Ayako’s expression was cool as ice. She winked again. I almost fell off the bunker myself.

‘Hey, come on! I don’t want to be the only one naked here!’

I looked down at the beach and saw Hidetaka, fully nude, cupping his hands over his groin.

‘Where the hell’s your pubic hair, Hidetaka?’

‘I shaved it off! The ladies love it!’ He threw up his hands, realised he had revealed all, then quickly covered his penis again. ‘Whoops!’

Ayako threw her bra at Hidetaka, covering her breasts with the other arm. They looked a lot smaller out in the open. She must have been wearing a bra with padding in it. That didn’t change a thing.

‘Look away you perverts!’

I turned my back to her, blushing red as a cherry blossom. I kicked off my trousers and dropped my pants, cupping my groin at all times. I had a second wave of terror at the thought of getting an erection. It was bitterly cold but for some reason that was only making it worse. The wind on my balls was like that awful peppermint shower-gel.

‘Okay you can look now!’

I looked over my shoulder and saw Ayako, one hand over her chest, the other between her legs. It reminded me of a painting I’d seen in a museum in London: Aphrodite, or as the Romans called her, Venus, emerging from the clam, shrouding her sex, the mystery of it so evocative, so primal. I think, sometimes, there is an honesty in western work that is mistaken by people like Hidetaka as primitiveness. By the same token, westerners do not understand the expressive nuance of eastern art and thereby think it is all the same, or else, repressed.

Ayako stepped from her pile of shed clothing, legs supple as the deer that roam Nara; she looked unearthly. Nothing like the painting. Her skin was tanned, not white. Her hair was black, not red. Her bust was small. But she looked – to use a western word – like heaven.

‘Okay go!’ Hidetaka roared.

We ran, the sand like cold rice beneath our feet. As we touched the water, all three of us let out a scream. A wave came in, slapping our knees out from under us. We toppled in, yapping like wild animals, foam washing over us. This was a different cold, a cleansing, cold that made me think of draughty temples, of silence, of something understood.

Yet, we were not silent, but screaming with delight. Hidetaka shook his hair like a shaggy dog and sprayed our faces with freezing water. I felt every droplet, as though I was perceiving the world in slow motion. Ayako splashed him back with both hands, no longer concerned with covering herself up. What was there to cover? We are all human.

I was rock-hard beneath the water. My erection fears had come true. I swam out, crawling through the waves, feeling the pull on my back muscles, tasting the salt, the richness of it, thinking of a thousand delicious meals in that moment. I plunged my head beneath the water, letting the cold engulf me, feeling held in that dark place, feeling my mother again in the shushing of the waves above, heard only dimly, as though through the veil of a dream.

When I emerged, the others were calling my name.

‘There you are! We thought you’d drowned!’ Hidetaka splashed towards me, put his hands on my shoulders. I prayed my erection did not touch him beneath the water.

I gripped his shoulders in return.

‘Ikigai!’ I bellowed it at the top of my lungs.

‘Ikigai!’ He and Ayako chorused me. I threw Hidetaka into the water. Ayako waded out to us, began splashing us with flecks of foam. I dived under, re-emerged, threw water at her. We played like children until light crept across the ocean, banding the glistening water with incomplete halos. The sea turned translucent, the sand beneath shimmering like undiscovered gold.

‘Ikigai,’ I said again, this time just to myself.

‘Let’s get back.’ Ayako beckoned to us. We ran as fast as we could for the shore (thankfully my erection had finally died down), towelled ourselves off, then dressed again, sheepish as children. I became aware of Ayako, as though seeing her for the first time; her beauty, as the sun stripped away all shadow from her, was as complete and holy as tanku. I imagined, somewhere far off, a bell tolling, once for each of the 108 illusions, my addictions and vanities being stripped from me, until there was only the contemplation of that which was perfect and beatific.

We sat, shivering a little, opening the last beers. We cheered in the European fashion and drank. The Asahi had been left out of the cooler and so was lukewarm but we were glad of it.

‘Pin,’ Hidetaka said, slowly.

Me and Ayako shared a look. Ayako was sitting to Hidetaka’s left, between us.

‘Pon,’ she said.

‘Pan.’ I pointed at Ayako.

‘Pin.’

‘Pon,’ I chimed.

‘Pan.’ Hidetaka pointed at me.

‘Pin!’

Ayako cried out ‘Pon’, being the first to miss the pattern. Together, me and Hidetaka chanted iki iki iki even though we weren’t drinking Ikis. She downed her drink.

‘Wuhoo!’ Hidetaka roared, rocking back on his butt, balancing with his two legs in the air, like a freeze-frame of someone falling off a roof. ‘Who needs video-games, eh Ryu?’

‘Yep. I never could have made a better game than Pin Pon Pan.’

‘Kuso! Now I don’t have a drink left!’ Ayako pulled a pouty face.

‘Have mine.’ I handed her the Asahi, stood up, and dusted my hands of sand. ‘Hidetaka, can I talk to you for a second?’ I winked at Ayako. ‘Boy talk.’

‘Ooohh.’ But she didn’t ask. Again, I thought about whether she already knows.

Hidetaka got to his feet, outrageously lurching. He looked like a parody of drunkenness: Jackie Chain in the Drunken Master