18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

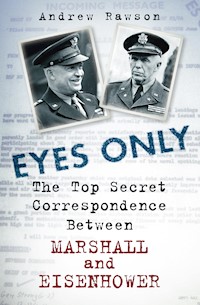

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

When you arrived at work today, what was on your to-do list? On 6 February 1944, this landed on the desk of General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the United States Army, a request from General Dwight D Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe: 'Count up all the divisions that will be in the Mediterranean, including two newly arrived U.S. divisions, consider the requirements in Italy in view of the mountain masses north of Rome, and then consider what influence on your problem a sizable number of divisions, heavily engaged or advancing rapidly in southern France, will have on OVERLORD.' It puts that late delivery or forgotten invoice into perspective. Eyes Only is not a history of the campaigns that swept across Europe between June 1944 and May 1945 – it is military command at its rawest, in real time and with no benefit of hindsight. It follows the planning, execution and aftermath of the campaigns through the highest security level day-to-day correspondence between the two Generals; the 'Eyes Only' cables. These candid words passed over their desks between December 1943 and December 1945, here fully annotated with background information. The cables start with the fraught six-month planning period for D-Day, followed by the establishment of the beachhead and the exhilarating advance across France. A difficult winter followed, culminating in attack and counterattack in the Ardennes. As Germany's collapse became imminent, attention focused on how to conclude the war without coming into conflict with the Soviet Army. After V-E Day, the problems of occupying Germany, de-Nazification, redeployment and humanitarian efforts are all on the agenda. Messages from the key politicians – Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin – are included. The two Generals have to deal with differences between the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the British Chiefs of Staff, the effect of the Mediterranean battles on the Western Front campaign — and of course 'man management' of figures such as Patton, Montgomery and de Gaulle. Judge for yourself how two of the United States' greatest military leaders dealt with the burden of command in the eye of the storm of history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

Introduction

1 December 1943—January 1944, Setting Up SHAEF and Choosing Commanders

2 February 1944, Landing Craft Shortages; Can Southern France be Invaded?

3 March 1944, Concerns over the Italian Campaign while Organizing Support

4 April 1944, Discussions over Operation ANVIL and Patton Speaks Out

5 May 1944, Dealing with French Issues and Last Minute Problems

6 June 1944, Operation OVERLORD and Securing the Normandy Beachhead

7 July 1944, The Battle of the Bocage and Changes in Command

8 August 1944, The Breakout Begins and the Invasion in Southern France

9 September 1944, The Race Across France and Operation MARKET GARDEN

10 October 1944, Logistics Problems and Supply Shortages

11 November 1944, Grinding along the Siegfried Line and Rear Area Dilemmas

12 December 1944, The Lull Before the Storm and the Battle of the Bulge

13 January 1945, Erasing the Bulge and Plans for Defeat of Germany

14 February 1945, Slow Progress toward the Rhine in Atrocious Weather

15 March 1945, Crossing the Rhine and Plans for the Final Battle for Germany

16 April 1945, The Collapse of Nazi Germany and Meeting the Soviet Army

17 May 1945, VE-Day and Tense Times with the Russians and the Czechs

18 June, July and August 1945, Occupying Germany

19 October 1945, De-Nazification and a Looming Humanitarian Crisis

Epilogue

Plate Section

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

This book is not another history of the European campaign; this is the story of two men and the immensity of their appointments. This first man is General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the US Army, from September 1939 to November 1945. The second is General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force from December 1943 to December 1945.

The text in these pages is the transcripts of the EYES ONLY cables between Marshall and Eisenhower between January 1944 and July 1945. There are also transcripts of cables issued by General Walter B. Smith, Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff before, during and after this period. The cables came at the top of the highest secrecy hierarchy, of EYES ONLY, TOP SECRET and SECRET. They went from Marshall’s desk to Eisenhower’s desk, or vice versa, and to no one else except their Chiefs of Staff.

This book is not a combined biography of the two great men either. Neither Marshall nor Eisenhower gave commentaries on their work or responsibilities. Instead the cables tell us what they were dealing with on a daily basis, providing primary source material at its best. Usually the discussions are about what might happen in the days and weeks ahead and the decision taken to stop a problem arising or minimize it. The cables tell us what the Pentagon and SHAEF knew about what was happening behind German lines; more often than not it was very little and sometimes mere speculation. Occasionally we get glimpses of just how little the Chief of Staff knew about the conduct of the European campaign, illustrating to what extent Eisenhower was left to get on with the war against Nazi Germany.

While this book is not a complete history of the war in Europe, it does reveal both how the Allies conducted the campaign and the debates that dictated why it was conducted as it was, more than any post-war diary or history. Within these pages are references to some of the most important periods of the war: the six-month build up before D-Day; the 18-month campaign across France, the Low Countries and Germany; and the difficult four-month negotiation period with the Soviets over the future of Europe.

The cables also give us a detailed insight into the day-to-day problems that Marshall and Eisenhower faced. Their in-trays were always full, both with unexpected crises, and issues that had been anticipated well in advance. The German military sometimes seems to be the least of Eisenhower’s problems as he tries to find solutions to issues raised by allies, politicians and subordinates. One day he was dealing with correspondence from Roosevelt or Churchill, the next a recalcitrant general.

Time was a precious commodity for both men. Marshall not only had to keep his eye on the war in Europe, but also had to deal with a similar range of problems in the Pacific, overseeing the provision of men, commanders, equipment and supplies in both theaters. On top of all that he had the generals and politicians to deal with in Washington DC. Eisenhower was also a busy man. As well as dealing with his superiors across the Atlantic, he had his three army group commanders and their army commanders to contend with. The rivalry of Montgomery, Bradley and Devers was a continual problem, as was that between Hodges, Patton, Patch and Simpson. Add to that the national differences between the Americans, Canadians, British and French, and it is easy to see why Eisenhower had to be as much a master of diplomacy as of military matters. When the likes of Churchill, de Gaulle and US politicians are added to the equation, it is a wonder that Eisenhower found time to attend to SHEAF’s needs.

The Procedure for Sending Cables

Each message had to be dictated, typed and encrypted before it was sent. On receipt it was deciphered and typed out before being delivered straight to the recipient’s desk; because ‘Eyes Only’ meant exactly that; the cables were written at Marshall’s desk and read at Eisenhower’s desk, and vice versa. Maximum security was used for these highly sensitive transmissions and no one else was allowed to read them without the recipient’s permission.

Each cable had the acronym of the sender and recipient at the top; AGWAR for Marshall and either SHAEF MAIN or SHAEF FORWARD for Eisenhower. The way the cables were written made sure that the recipient knew they were of the top level of secrecy. The first line of a cable contained only a vague reference to the contents and the reference number of the cable it was referring to, if appropriate. It was followed by the words EYES ONLY and the surnames of author and the recipient, all underlined. The text followed.

The cable clerk was left in no doubt what they were supposed to do with the document as soon as it had been decoded; a huge stamp was used to make sure that the words EYES ONLY appeared at the top of the page. The recipient could add a distribution and action list once he had read the document. All cables were dated and timed and had a unique reference number, the current number in the sequential numbering systems of all cables sent from the forwarding office. This was done so that the list of EYES ONLY cables would not stand out as having special content and alert the German code breakers.

Transmission and Receipt Locations

At the start of the Second World War the bulk of the War Department offices were housed in the Munitions Building, along Constitution Avenue on the National Mall in Washington DC. It was a temporary First World War era complex and offices had spread out across the city and beyond. Although a new block had been built in the in the Foggy Bottom area in the late 1930s, the War Department was still too cramped and spread over too many buildings to be efficient.

The outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939 meant a new expansion of the US Army and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson asked President Roosevelt for a new purpose-built structure in May 1941. By July Congress had agreed and allocated the money for what would become the Pentagon, the huge five-sided building we know today in Arlington, on the west bank of the Potomac river. Work was undertaken at a rapid rate over the winter of 1941/42 and by April the first group of offices was opened. The building only took sixteen months to complete.

Across the Atlantic, SHAEF headquarters staff started work under the streets of London in purpose-built air raid shelters in Goodge Street Underground Station. However, Eisenhower and his Chief of Staff, General Walter B. Smith, found working in Central London to be claustrophobic. The number of unwanted visitors, particularly British visitors, to SHAEF’s headquarters was another reason for wanting to move out of the city. A temporary headquarters was built in the Teddington End of Bushey Park, near Kingston-on-Thames, ten miles southwest of Central London. It was codenamed WIDEWING. During the run up to D-Day a small command post, codenamed SHARPENER, was established near Southwick, just north of Portsmouth. There Eisenhower was close to his troops and far from prying eyes. His personal office tent and sleeping trailer stood next to a mobile office and telephone switchboard. They were surrounded by trailers filled with maps and teletype machines, including one for the EYES ONLY cables from General Marshall. Tents for aides, guards, cooks and the all-important meteorologists – Group Captain James Stagg, RAF, Donald N. Yates, USAF and Sverre Petterssen, Norwegian Air Force – completed the camp. SHAEF continued to operate from WIDEWING but an advanced headquarters, known as SHAEF Forward, was established on the continent in August. SHAEF was established in the Trianon Palace Hotel in Versailles, France, by the time of the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, and at the end of April 1945 it moved to Frankfurt. SHAEF came to an end on 14 July when all US armed forces came under US Forces, European Theater (USFET).

Locating the Cables

The road to finding these fascinating primary sources began when I was working on a Masters of Philosophy Degree thesis under Professor Gary Sheffield, with the University of Birmingham’s School of Modern and Medieval History between 2007 and 2011.1 My subject was ‘The Divisional Commander in the US Army in World War II’ and I was studying the group of 24 general officers who commanded divisions during the Normandy campaign in June and July 1944 as a sample.

A structured investigation of what documentation should be available was put together under my tutor’s guidance. Eisenhower changed a number of divisional commanders during the European campaign, but where was the correspondence documenting the reasons for the changes? Although my research began with the start of the generals’ careers before the First World War, selection did not really start until 1939. On 1 September 1939, German troops invaded Poland and two days later Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. Coincidently Brigadier-General George C. Marshall was appointed Chief of Staff of the US Army and promoted to full General on the same day in Washington DC. Another key appointment was made in July 1940, when Brigadier-General Lesley J. McNair became Chief of Staff at General Headquarters, US Army.2 Marshall and McNair together chose the divisional commanders in the US Army during the early months of the war. By the summer of 1940, Nazi Germany occupied most of Europe and President Roosevelt responded by declaring a limited National Emergency starting in October 1940. It sanctioned preparations for defense of the western hemisphere under the plan codenamed RAINBOW I.

RAINBOW I also called for a huge expansion of the army and hence the appointment of many new corps and divisional commanders. In July 1941, McNair drew up a list of names for Marshall, short-listing ten brigadier-generals and fourteen colonels as ‘suitable candidates for divisions’.3 The four senior American commanders on D-Day in June 1944 were on McNair’s list: Dwight D. Eisenhower (SHAEF), Omar N. Bradley (First US Army), J. Lawton Collins (VII Corps on Utah Beach) and Leonard T. Gerow (V Corps on Omaha Beach). Continuous outstanding performance during peacetime had been recorded in their 201 Personnel Files as their General Efficiency Rating, a number ranging from the best at around 6.5 to the worst at around 4.5.

Part of the army’s increased budget for 1941 was used to fund large scale military maneuvers in Louisiana State, and while they proved useful for testing tactics and doctrines, the majority of incumbent general officers were found to be unsuitable. ‘Most of the 42 division, corps and army commanders who took part in the GHQ maneuvers were either relieved or reassigned to new commands in 1942 (including 20 of the 27 participating division commanders).’4 McNair and Marshall had a lot of work to do.

On 7 December 1941, Japanese planes attacked the naval bases at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and in the Philippines. The US responded by declaring war on Japan. Four days later Germany declared war on the US as it entered a world war for the second time in its history. US divisions started training in earnest, and command changes were implemented at a rapid rate in the pursuit of efficiency. Most of the 20 divisions destined to fight in Normandy in the summer of 1944 had more than one commander in a short space of time as generals were promoted, reassigned, sacked or retired. In January 1944 Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, SCAEF. It was now his turn to see how the general officers under his command shaped up. With the help of his subordinate commanders, General Omar N. Bradley, General Courtney H. Hodges and General George S. Patton, assessments of the divisional commanders were made.

While I found some information on the reasons behind the selection of some commanders in the National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland, the two-stage ordering system – involving searching the microfilmed indexes to locate possible useful documents – was a lengthy process and I was running out of time. Emails to the George C. Marshall Research Library led me to believe there was a microfilmed copy of the documents down in Lexington, Virginia. Opened in 1964 in the grounds of the Virginia Military Institute – where Marshall started his military career, graduating in 1901 – the Foundation houses both the George C. Marshall Research Library and the Marshall Museum. It was there that I struck a rich seam of information.

After searching through the correspondence between Marshall and McNair, I came across the Marshall and Eisenhower cables: Microfilm 184, a single microfilm reel with Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff, General Walter Beedle Smith’s 1288 pages of cables and indexes. There was a discreet handwritten numbering system given to each cable by Smith, nickname ‘Beetle’. He also added the numbers of any relevant cables in his EYES ONLY file and his own private index. It was a simple yet effective way of keeping track of what issues were in Eisenhower’s in-tray.

The cables were microfilmed chronologically, and while that system was logical for General Smith, it is not the best way to read them so a different system had to be used. After transcribing all the cables, they were sorted into topics. Quite often there was a question raised and an answer given, usually within 24 hours. Some topics run over several cables as the debate continues. Occasionally, a cable contains two entirely different themes and the author made it absolutely clear when he was switching topic with the words NEW SUBJECT. These entries have been split between the two relevant conversations. The topics were then organized into chronological order, using the date of the original question to organize them. This method allows the reader to follow each discussion from beginning to conclusion without interruption.

Alterations

The absolute minimum number of alterations has been made to the cables. Spelling and grammatical errors have been corrected, but they were few. The code clerks made very few mistakes and most of those were connected to names, particularly foreign surnames and European place names. Some long sentences have been given the benefit of a comma or semi-colon to allow for easier reading, as the clerks were very sparing with punctuation. Similarly the word ‘the’ was often omitted, probably because that was the way that cables were dictated, in short snappy phrases, and a few have been added to improve understanding.

In general however, the cables have been left as they were, giving the reader an insight into the language of the day between senior military and political individuals. We see how the likes of Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin addressed Marshall and Eisenhower and vice versa, and even glimpse occasional snatches of humor. There are also angry exchanges, although never between the two generals, rather they vented their frustration over the shortcomings, failings or attitudes of others.

A Word on Footnotes

The transcripts have been extensively annotated to enhance the reader’s understanding of the EYES ONLY cables. Many of the notes simply expand on a discussion, adding detail and statistics. Some explain the circumstances surrounding a sequence of cables, either what brought about the discussion or what was the final outcome.

High ranking personnel were referred to by surname, while lower level officers were referred to in full. Virtually all the names quoted in the text have been identified with their full name and occupation at the time of the cable. Operational codenames are referred to at regular intervals and are written in upper case. While some are well known, many are not, and the codenames are identified, with details of the operation and its outcome.

In many cables we learn about military plans long before any action is due to occur. When appropriate the notes reveal the details of the planning as the discussion unfolds. In this way the reader learns about the twists and turns as a debate intensifies. Sometimes we learn about a plan which is later cancelled or superseded; the pertinent notes explain the reasons for this.

Omissions

While there are over 120,000 words in the Eyes Only cables in this book, another 35,000 have been left out. These have been omitted owing to their content, often referring to simple administrative matters. In the six-month period before D-Day, the cables that have been left out fall into two main categories. Firstly, the debate over the organization of various support services, as a great deal of them were speculative discussions and the ideas never came to fruition. The main services omitted include the Civil Affairs Organization, Signals, Base Sections, Transport, Press Relations and War Crimes. Discussions over appointments and promotions of general officers serving with these supporting services have also been omitted, as well as routine requests relating to appointments of staff officers serving with armies and corps. Once the European campaign got underway, Eisenhower had to submit monthly promotion lists to Marshall, including the details and justification for choosing each officer. While higher level promotions have been included, with the emphasis on well known generals, those of lower level officers, typically colonel to brigadier, have been omitted. Mutual awards between the US and British Armies have also been left out; Montgomery often suggested British awards for American generals and troops serving with 21st Army Group.

Another set of cables omitted are those sent after the 15 August landing on the south coast of France. General Devers sent daily detailed troop movements to SHAEF headquarters, and while the general progress of Operation DRAGOON is given, the details of the advance are not. Similarly, the various travel arrangements of generals and politicians visiting the European Theater and mutual travel arrangements with Montgomery have been left out. A detailed discussion of arrangements for Marshall’s stopover in France en route to the January 1945 conference in Malta, codenamed ARGONAUT and CRICKET, is also omitted. During Marshall’s occasional visits to Eisenhower, cables from Washington DC and the Pacific were forwarded to SHAEF headquarters for the Chief of Staff’s attention. While these cables are important in the story of the war as a whole, they are not relevant to the European Theater. It does beg the question whether a similar collection of the Eyes Only correspondence between Marshall and the Pacific Theatre could be assembled for a similar study.

A prolonged discussion over arrangements for a Japanese regiment to serve on the Italian Front in February 1945 is also omitted. The battalion was made up of soldiers of Japanese origin who had been living in the US at the outbreak of war.

As the war drew to a close, issues relating to demobilizing the Allied armies had to be addressed, and while many of the relevant cables are included, two marginal sets are not. One set details the discussions over the determination of ROGER Day, or R-Day, the set date for determining schedules to return troops to the US or to the Pacific campaign. The issue was relatively minor, and the fact that the date ultimately chosen was the same as Victory in Europe Day, or V-E Day, meant that the discussions were immaterial. The second set of cables omitted relates to arrangements made for bringing the generals home and their placing with Home Commands.

Three main post-war subjects have been omitted. The first concerns the politics relating to the setting of the boundaries of the French Zone of Occupation, as details of map references and lists of districts make tedious reading. The other subjects are the initial plans for Public Relations and Civil Affairs in occupied Germany.

Throughout the cables, comment on what has happened on the ground is rare, and although Marshall asks Eisenhower for weekly debriefings on the progress of the advance through France in the summer of 1944, these soon tail off. Only Devers makes the effort, forwarding details of the spectacular advance through southern France following Operation DRAGOON (previously ANVIL). Marshall had the foresight to leave Eisenhower alone during busy periods such as those around D-Day, Operation MARKET GARDEN in September and the Battle of the Bulge in December. By the time the troops were in action the problems had been discussed, differences had been aired and solutions had been agreed. The two men rarely discuss the progress of a battle; they are too busy considering what comes next.

We do learn how the three army groups discuss plans and report on operations, although not as often as one might think. On the whole, details about military operations rarely appear in the Eyes Only cables although future operations were occasionally considered; Montgomery regularly put his thoughts on the future of the campaign to Eisenhower. Operations were usually planned and orders given well in advance and the paperwork was issued accordingly. Cables were only issued to army group headquarters when last minute changes had to be made; the famous example is Eisenhower’s strategic plan issued at the start of the Battle of the Bulge in December 1945.

The Value of Primary Source Material

Many historians have written about the planning and execution of the European campaign in 1944–45, some on the whole campaign, many on selective aspects of it. Some place emphasis on the Marshall and Eisenhower partnership while others focus on the military side of the campaign. While these books give the reader insights into the campaigns and professional relationships, they are inevitably subjective, some more than others. Some historians stick to the facts, while others endeavor to increase the tension or interest in an event with speculation. One example of this is the relationship between Eisenhower and Montgomery, 21st Army Group’s British commander. At times it has been fashionable to accentuate their apparent mutual contempt in the interests of a good story. It is true that they came from different backgrounds and had different views on many things, as independently minded generals should have. However, the cables reproduced in this book give us an insight into the true nature of the professional relationship between these two men when they dealt with important strategic matters, without the distortion of a historian’s speculation.

Another example is what became known as the ‘Knutsford Affair’ at the end of April 1944. Patton made outrageous statements in front of a group of people, unaware that a member of the press was in the audience, and there were calls for his dismissal. Historians make different assessments of Patton’s behavior and they range from calling him a misunderstood genius to an unstable leader. The week-long trial by cable and the eventual outcome of the affair are reproduced here in the blow-by-blow discussion between Marshall and Eisenhower.

Eisenhower’s controversial decision to halt the Allied armies’ advance along the river Elbe, leaving Berlin to the Soviet armies, has been argued over by historians for many years. Some state that it was the worst decision he made with hindsight of what happened in the Cold War years in Europe. Only when you read his justification to Marshall and Churchill do you get an insight into the great burden of command placed on SHAEF commander’s shoulders. Having read what his reasons were for halting his armies where he did, we, the reader and armchair historian, understand what issues were on his mind. We can never fully understand what it is like to bear the pressures of decisions such as these.

One thing that is clear from these cables is the strong commitment between Marshall and Eisenhower. Mutual support is shown before, during and after the European campaign, even during the most difficult times. The media were repeatedly stirring up issues that the two had to discuss, and more often than not they decided that the best course of action was not to rise to the bait, letting the stories run their course. Over time some of these press speculations, repeated again and again, became cast in historical stone. These cables strip back stories to their origins so we can discover the reaction at the time. Finally, Eisenhower’s cable of gratitude on 8 May 1945, the day the official German surrender was signed, illustrates how deeply Marshall’s commitment to supporting SHAEF was appreciated.

It is hoped that by studying the messages the reader will gain a remarkable insight into the roles of two great men, General George C. Marshall and General Dwight D. Eisenhower, in the Second World War.

Biographies

General George Catlett Marshall, General of the Army (31 December 1880–16 October 1959) Marshall grew up in Uniontown, Pennsylvania and enrolled at the Virginia Military Institute, graduating in 1901. He was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Infantry in February 1902, serving in the Philippines and Oklahoma before attending the Infantry-Cavalry School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Marshall was promoted to 1st Lieutenant in 1907 and after graduating in 1908 he stayed on as an instructor for two years.

Over the next seven years Marshall served as Inspector-Instructor of the Massachusetts National Guard, with an infantry battalion in Arkansas and Texas and again in the Philippines. During his stay there he worked with the Field Force organizing it for the defense of Corregidor Island and the Bataan Peninsula, serving with it during a field exercise representing a Japanese landing on Batangas and Lucona.

He was promoted to captain on his return to the US in the summer of 1916, serving in several staff posts before America entered the First World War in April 1917. He joined the General Staff and sailed with 1st Division’s first convoy for France; he was promoted to temporary major on his arrival. He served in the Luneville sector, the St Mihiel sector and the Picardy sector over the next twelve months and was promoted to temporary lieutenant-colonel. He was promoted to temporary colonel in August 1918, and assigned to the US Expeditionary Force’s General Headquarters and then First Army as he drew up the plans for the St Mihiel offensive. As soon as the battle got underway in September he was tasked with planning and executing the transfer of 500,000 troops and 2700 guns to the Argonne Front. He was appointed First Army’s Chief of Operations during the middle of the Meuse-Argonne battle in October. After serving as VIII Corps’s Chief of Staff following the Armistice in November 1918, Marshall’s last task in Europe was to help plan the advance into Germany at General Headquarters.

Marshall served as General John Pershing’s aide-de-camp for the next five years and had been promoted to lieutenant-colonel by the time he took command of a battalion in Tientsin, China. After serving as an instructor at the Army War College, he was assistant commandant of the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia from 1927 to 1932, implementing many changes in how the school was run. He was then promoted to colonel and over the next four years he commanded a battalion and served as senior instructor with the Illinois National Guard. Following his promotion to brigadier-general in July 1936 he commanded 5th Infantry Brigade.

In July 1938 Marshall joined the War Department General Staff, War Plans Division and by October he was Deputy Chief of Staff. After heading the Military Mission to Brazil in the early summer of 1939, he was appointed acting Chief of Staff of the Army in July and promoted to major-general. He became Chief of Staff and full general in September. He would serve as the US Army’s Chief of Staff throughout the Second World War and was promoted to the new temporary five-star rank of General of the Army on 17 December 1944; this was made permanent in April 1946. Marshall centralized the professional leadership of the US Army and exercised control over mobilization, staff planning, industrial conversion and personnel requirements. His austere, aloof manner was well known in army circles and his succinct methods were put to good use streamlining administration and tactical organization.

Marshall resigned from the US Army in November 1945; his many decorations included two Distinguished Service Medals and the Silver Star. But his activities were far from over. Marshall acted as President Truman’s personal representative to mediate peace between the nationalist and communist Chinese in 1946, and he went on to serve as Secretary of State from January 1947 to January 1949. In April 1948 he was a proponent of the plan for the economic recovery of Europe; the US contributed over $112 billion to the ‘Marshall Plan’. He was also Secretary of Defense from September 1950 to September 1951.

Marshall served a term as President of the American Red Cross and as chairman of the American Battle Monuments Commission for ten years. He was awarded a gold medal from Congress and the Nobel Peace Prize in September 1950 for his work.

The great man who Churchill called the ‘true architect of victory’ of the European Theater in the Second World War died in Washington DC on 16 October 1959. He was buried with full military honors in Arlington Cemetery, Arlington, VA.

General Dwight David Eisenhower (14 October 1890–28 March 1969)

Eisenhower was born in Denison, Texas but his parents moved back to their roots in Abilene, Kansas when he was two. After graduating from high school he worked in the local creamery for two years before deciding to join the armed services. He entered United States Military Academy, West Point, in June 1911 and graduated four years later, having acquired the nickname ‘Ike’. He was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in September 1915 and posted to Fort Sam Houston, Texas, where he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant in 1916.

Eisenhower was promoted to captain in May 1917, a month after the US entered the First World War. Rather than head for France, he stayed in the US, serving with infantry units, teaching at army schools and working with army engineers. By the time of the Armistice he was a temporary lieutenant-colonel, and although he was reduced to the permanent rank of major, he commanded several tank battalions over the next three years.

Following a two-year posting in the Panama Canal Zone, Eisenhower attended the Command and General Staff School, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, graduating first in a class of 245 in June 1926. After a brief period as a battalion commander, he worked for the American Battle Monuments Commission in Washington DC and Paris, France, until September 1929, graduating from the Army War College, Washington DC, in August 1928.

After serving as the Assistant Secretary of War’s Executive Officer, he then worked for General Douglas MacArthur, Army Chief of Staff, from 1933 to 1939, first as chief military aide and then as Assistant Military Advisor to the Philippine government. During this period he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in July 1936. He served on the staff of an infantry regiment and then as regimental executive until he was appointed in quick succession, Chief of Staff for 3rd Division, Chief of Staff for IX Corps and Chief of Staff to Third Army during the Louisiana Maneuvers. During this time he was promoted to brigadier-general.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower joined the War Plans Division of the War Department General Staff and was appointed Chief of the War Plans Division in February 1942. In April 1942, Major-General Eisenhower began working for General George C. Marshall as Assistant Chief of Staff of the Operations Division.

In June 1942 Eisenhower was appointed Commanding General, European Theater and appointed Lieutenant-General shortly afterwards. His appointment was renamed Commander-in-Chief, Allied Forces, North Africa, as US troops stepped ashore in Operation TORCH in November 1942. Over the next twelve months his command fought its way across North Africa, invaded Sicily and mainland Italy; he was appointed temporary full general in February 1943 and permanent major-general in August.

In December 1943 Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Forces. Over the next six months SHAEF planned for the invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe, landing in Normandy on 6 June 1944. For the next six months Eisenhower’s command repeatedly pushed back the Wehrmacht to Germany’s borders; in December Eisenhower was promoted to General of the Army with five stars. Shortly after the German surrender on 8 May 1945, he was appointed Military Governor of the US Occupied Zone of Germany.

Eisenhower returned to the US in November 1945, replacing Marshall as Chief of Staff, US Army. He served as President of Columbia University, New York City, from June 1948 but in December 1950 he was recalled to active duty. He was named Supreme Allied Commander, North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Europe, and given operational command of both the Treaty Organization in Europe and US Forces, Europe.

Eisenhower retired from active service in May 1952 and a month later announced his candidacy for the Republican Party nomination for President. He was elected President of the United States on 4 November 4 1952, going on to serve two terms from 20 January 1953 to 20 January 1961. His administration experienced difficult times, including the end of the Korean War, the promotion of Atoms for Peace, and the crises in Berlin, Hungary, Lebanon and Suez. At home, issues included civil rights and the growth of the interstate highway system; Alaska and Hawaii also joined the United States.

Eisenhower died on 28 March 1969 and was buried in the Place of Meditation at the Eisenhower Center in Abilene, Kansas. His many decorations included six Distinguished Service Medals and the Legion of Merit; he was also author of Crusade in Europe (1949) and Mandate for Change (1963).

Walter Bedell ‘Beetle’ Smith (9 August 1895–5 October 1961)

Smith grew up in Indianapolis, Indiana, and although he left high school without graduating, he attended university. He had to drop out to support his family when his father became ill, and he enlisted as a private in the Indiana National Guard in 1911. Smith was commissioned as an officer on the United States’ entry into the war in April 1917 and sailed with 4th Division to France in May 1918. He was wounded during the Aisne-Marne Offensive in July 1918.

Smith returned to work in the Military Intelligence Division of the War Department General Staff and served briefly with 95th Division before dealing with the disposal of supplies during the demobilization period. He joined the 2nd Infantry in March 1919, becoming staff officer 12th Infantry Brigade in 1922. He served in the Bureau of the Budget from 1925 to 1929 and was promoted to captain before he left to serve in the Philippines. On his return in March 1931 he became an instructor at the US Army Infantry School, serving there on and off until September 1939, becoming a major in January of that year. He graduated from the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1933 and the Army War College in 1937.

Smith was appointed Secretary of the General Staff in 1941 and Secretary to the Combined Chiefs of Staff the following year. During his time in the War Department he prepared records, paperwork and statistics whilst carrying out analysis, liaison and administration; he also often had to brief President Franklin D. Roosevelt on strategic matters. Although Smith was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in May 1941, colonel in August 1941 and brigadier in February 1942, he was disappointed not to be given an operational command.

He became Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff at Allied Forces Headquarters (AFHQ) in September 1942 where he used a combination of fine diplomatic skills and brusque demands to get his way. He worked alongside Eisenhower during the North African and Sicilian campaigns and negotiated the Armistice between Italy and the Allied armed forces in Sicily in September. In December 1943, Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Allied Commander for Operation OVERLORD, the invasion of Normandy. A month later Smith was promoted to lieutenant-general and appointed Chief of Staff of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF).

In August 1945 Eisenhower nominated Smith as his successor as commander of US Forces, European Theater (USFET) but the post was given to General Lucius D. Clay. When Eisenhower was appointed Chief of Staff of the United States Army in November 1945, he took Smith as his Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations and Planning. President Harry S. Truman then appointed Smith as the US Ambassador to the Soviet Union at a time when the Cold War was in its infancy. Smith saw the Soviet Union as a totalitarian and secretive state and his views were treated with suspicion. He returned to the US in March 1949 and became commander of First Army; it was his first command since 1918.

Smith was appointed head of a dysfunctional Central Intelligence Agency in 1950, at a time when the US was involved in the Korean War. He successfully reorganized the establishment into three directorates: Administration, Plans, and Intelligence and was promoted to four star general for his efforts in August 1951.

Although Smith retired from the US Army and the CIA in February 1953, he immediately became Under Secretary of State in the new Eisenhower administration. After failing to get British help for the French during their conflict in southeast Asia, he forged a deal with the Soviets to partition Vietnam in May 1954. He retired in October but continued to work in the Eisenhower administration in various posts. He went on to serve as a Member of the National Security Training Commission from 1955 to 1957, on the National War College’s board of consultants from 1956 to 1959 and the Office of Defense Mobilization Special Stockpile Advisory Committee from 1957 to 1958. Smith was also a consultant in the Special Projects Office (Disarmament) in the Executive Office of the President from 1955 to 1956, the President’s Citizen Advisors on the Mutual Security Program from 1956 to 1957. He then served on the President’s Committee on Disarmament in 1958 and was Chairman and member-at-large of the Advisory Council of the President’s Committee on Fund Raising from 1958 until his death in August 1961. Smith was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia.

1 Birmingham, UK.

2 Temporary Lieutenant-General; McNair’s post was renamed Commanding General of Army Ground Forces in March 1942.

3 McNair, ‘Memorandum to Marshall, 8 July 1941’ (George C. Marshall Research Library, Lexington, VA, Marshall Papers, Pentagon Office Correspondence, Box 76).

4 Gabel, Christopher R., The US Army GHQ Maneuvers of 1941 (US Army Center of Military History, Washington, DC, 1991) p. 187.

1

DECEMBER 1943 AND JANUARY 1944

Establishing SHAEF Headquarters

Smith to Eisenhower

30 December

Ref: Algiers 21147

I have just received your 21147 and have given your message to General Wilson.1 He will await your return to take over command, and may go on to Cairo to pack during the interim.

Have yet had no time to go into living accommodation. Am sure the house offered by the Ambassador will not be satisfactory to you. He wants you to occupy one floor. I also believe that this Headquarters should get out of London at the earliest possible moment. Aside from the threat of bombing, I do not think we shall ever get shaken down until we get away from Norfolk House2 as the situation is the same as it was at the beginning of TORCH.3 I will talk over possible locations with Morgan.4

There are two things which you must discuss with utmost urgency while you are in the United States:

First is the Air Command setup covered by my message this morning. We all believe that the appointment of Tedder5 as Deputy Allied Commander without portfolio and Mallory6 as Air Commander-in-Chief will make a difficult situation. I personally believe that Tedder should be the real Air Commander and your advisor on air matters, which Mallory now considers himself. I don’t think there is a place for both of them.

There is also a question about Tactical Air Forces. These are now organized on a joint basis. Other than Mallory, who is Air Commander-in-Chief, there is no single Commander of the Tactical Air Forces as we had in the Mediterranean.

Both the above consistencies must be corrected and no formal directive should be issued by the Combined Chiefs of Staff until you and Tedder are both here and you make your own recommendations. The present organization of COSSAC Headquarters7 can be made to conform to the setup you want with the change of a few names and the substitution of a few individuals. However, the organization is very top heavy. I talked with the Deputy C.I.G.S.8 this morning on personnel and made some progress. Will see General Brooke9 this evening and Ismay10 tomorrow. Devers11 returns to Algiers with me and I will put him into the picture as rapidly as possible.

Suggest you leave the written memorandum authorizing Wilson and Devers to command to be delivered to me on my arrival, to be used if necessary.

Smith to Eisenhower

30 December

Ref: 6792

I have just had a talk with Wigglesworth12 and a preview of the command set-up proposed here. The thing which disturbs me the most is the proposed air command, which either leaves Tedder without any direct air function, with Mallory the Commander and principal advisor of the C-in-C, or, as an alternative, if you decide to make Tedder your air advisor, would leave Mallory without any function.13

I am also concerned about the plans here for the establishment of two Tactical Air Forces. Wigglesworth and I are convinced this is most unsound at the moment. Apparently this proposal is incorporated in a British Chiefs of Staff paper which has been, or is about to be, sent to the Combined Chiefs of Staff for approval and the issuance of a directive to the Allied C-in-C. Strongly urge that you send a message to General Marshall requesting that no action be taken by the Combined Chiefs of Staff on further command directives until you and Tedder are here and can be in the picture, and until you have had a chance to submit your recommendations.

Smith to Eisenhower

31 December

Ref: 6824

If C-in-C has already left, Gilmer forward to Galey in Washington.14 I find that the matter of air command of which I spoke has already been covered by Combined Chiefs of Staff directive issued some time ago. There is a difficult command situation from the air point of view, and I am meeting with Spaatz15 and Eaker16 tomorrow after which I will send you a long message to Washington.

I think accommodation provided will please you thoroughly. Very nice house in London, with all the facilities you like, including lots of fire-places. Either telegraph cottage or another one, very close for the country. Everything else in the way of accommodation is taken care of perfectly by Jimmy Gault’s17 arrangements. Telegraph cottage much improved since your occupancy, particularly from a heating stand point.

Have just had a long talk with C.I.G.S. Will probably get Gale,18 but not Strong19 except for a short time, to get things going in G-2. Other personnel requested will be available.

Making tentative arrangements for a very early move of this Headquarters to Aldershot. C.I.G.S. has been most helpful and only question now is of communications. Gault will immediately survey living accommodation in that area, and he thinks prospects are good.

General Wilson’s plans are now to go on to Cairo returning to Algiers shortly before your return. Spaatz’s plane will be available. Will not have to use the two documents I suggested.

Handing Over Command of the Mediterranean

Eisenhower to Smith

6 January 1944

Ref: 6490

Your telegram announcing arrival received. This morning I saw a telegram from AGENT21 to CARGO22 asking that Allied Command in the Mediterranean be transferred as of the 8th. I recommended to CARGO that he not only accept this, but to inform AGENT that you and I had foreseen this possibility and that I had left with you a written note authorizing General Wilson to take Command when he considered it necessary. In view of this development and the need for my going to the new station at the earliest possible date, I believe it would be best for me to go there directly from here. In this event Devers should also assume command of the American Theater on the date you and he may agree. Unless you find this plan completely unworkable I will tentatively plan to carry it out. However, I would like you to inform both Commanders that it would be my intention to come back to FREEDOM22 purely as a visitor within a week or ten days after I reach my new station merely to say goodbye to the many officers to whom I am indebted for fine service. I would count on staying there one day only.

I am leaving this city for a few days but essential messages can reach me. Please consult Colonel Lee23 as to possibility of moving all my personal belongings and personal assistants and domestics without awaiting my return. Ask him also to convey my warmest regards to all my personal family, including special American contingent.

Please take up the following with Tedder.

I anticipate that there will be some trouble in securing necessary approval for integration of all Air Forces that will be essential to success of OVERLORD. I suspect that use of these Air Forces for the necessary preparatory phase will be particularly resisted. To support our position it is essential that a complete outline plan for use of all available aircraft during this phase be ready as quickly as possible. I therefore believe that Tedder should proceed to the new station at once and consult with Spaatz and others in order to have the plan ready at the earliest possible date. In your reply please indicate how soon Tedder believes he can depart.

Eisenhower’s Departure for the United Kingdom

Eisenhower to Smith

13 January 1944

Ref: 7079

Under present schedule I leave here Thursday evening and arrive in Prestwick, via the Azores, on Saturday afternoon. I will go from Prestwick to London by train and arrive there Sunday morning. If Colonel Lee is still in your Theater please give him the essentials of the schedule. This information has already been sent to London and Colonel Gault. My arrival is to be kept secret.

I have taken up here the various matters raised by Montgomery24 and feel that the final decision may not be taken until I can arrive in London. I am almost reluctant to consider giving up ANVIL25 and still feel that through some expedient we can increase OVERLORD lift. There are certain weighty reasons other than strictly tactical that must be considered. Among these is denial to French Forces of a significant part in the French Invasion. Another is the fact that this Operation was definitely agreed upon at Tehran26 It is my belief that all the Chiefs of Staff will oppose us if we are forced eventually into the decision to abandon ANVIL27. On the other hand I think we can slightly diminish the Armored Landing Craft assigned that Operation in favor of OVERLORD.

I hope that the deal with respect to Morgan and Whiteley28 goes through as you suggested. I am also hopeful that you will not be delayed longer than the 20th.

Army and Corps Commanders in the Mediterranean

Marshall to Eisenhower

17 January

Ref: R-8213

After consultation with Alexander,29 Devers reports that Clark30 should retain command of the Fifth Army in Italy and not assume command of the Seventh Army for ANVIL as you planned. Middleton31 has been put in charge of ANVIL planning temporarily by Devers. Devers asks that Hodges,32 Simpson33 or any other of my choice be assigned immediately to the Seventh Army for ANVIL. ANVIL certainly requires an army commander with battle experience against the Germans. There are only three that appear to meet this requirement. Bradley34 of course, is not available. It rests between Clark and Patton.35 With Bradley, Hodges and Patton now set up for the U.K., there will be an extra Lieutenant General there until the Army Group Commander is designated. What do you think of Patton retaining command of Seventh Army and carrying out ANVIL?

I had thought that Clark would continue in command of Fifth Army until the Rome area was reached. Lucas36 would then replace him. Thereafter as soon as U.S. Divisions largely disappeared from Fifth Army line up, Clark Lucas would be replaced, probably by a Britisher, although maybe a French officer if such divisions are to compose the bulk of Fifth Army.

Devers also asked that an additional Corps Commander be sent to the Mediterranean to be used as relief for present Corps Commanders who are beginning to show the strain of extended combat service, in order to give them a rest, but not with the view necessarily, to their permanent relief. Give me your views on the advisability of replacing Woodruff,37 Crittenberger38 or Walker39 or possibly Cook40 who goes in April, by Collins,41 and sending whoever is thus replaced to the Mediterranean for Devers to use as a reserve commander. Also, for the extra Corps commander, let me know what you think of using Truscott.42

Marshall to Eisenhower

18 January

Ref: 9

Reference my R-8213 regarding Devers and ANVIL: In fourth paragraph, fourth line, the name Clark should have been Lucas, reading “Lucas would be replaced, etc.”

Since radioing you in this matter Devers has communicated his desire to make no changes – Clark to command ANVIL, Lucas to command Fifth Army and Truscott to command Corps.

Eisenhower to Marshall

18 January

Ref: 109737

My own understanding of the previously planned changes in U.S. Army command in the Mediterranean Theater agrees with yours. That is, Clark was to remain in command of the Fifth Army until completion of SHINGLE43 and would then be replaced by Lucas. Lucas would remain in command of the Fifth Army until the British finally took over, since I believe that after a channel of entry into France is opened up from the south, all the available American and French divisions would be absorbed in that venture. However, if both Alexander and Devers believe that General Clark should remain in command of the Fifth Army, then I am of the opinion that Patton would be the best man to plan and lead the ANVIL affair.44 This might prove especially advantageous if we are finally compelled to reduce ANVIL initially to the status of a threat rather than to mount it as a large scale offensive operation. Patton’s reputation as an assault commander, which is respected by the enemy, would serve to increase the value of the threat.45

To tell you one possible drawback to this plan, I must venture into the realm of conjecture. It is my impression that Devers and Patton are not, repeat not, genial. You see I am being perfectly frank with you have because I have nothing but impression on which to make the above statement. I think, however, that both of them are sufficiently good soldiers that possible personal antagonism should not, repeat not, interfere with either one doing his full duty as a soldier. On the favorable side of the picture and in addition to the consideration of Patton’s prestige, there is the factor that Patton is already on the ground, is well acquainted with and liked by the French, and is also well acquainted with such personnel of the Seventh Army staff as still remains with him.

Moreover, leaving Patton in the Mediterranean will allow Hodges to come here with his own Third Army staff with which he is, of course, thoroughly acquainted. I personally believe therefore that Patton should stay in the Mediterranean and Hodges should come here. Any decision you make will be acceptable to me. In this connection one of these two army commanders should proceed here soon and begin the necessary organization of an American army. You are quite right in your belief that there is no necessity at this moment to have three lieutenant-generals here but on the other hand two are required.46

With respect to corps commanders, it would appear that retaining Clark in command of the Fifth Army would prohibit the immediate promotion in the Mediterranean of Truscott to corps command, since Devers wants one who is fresh. Truscott has been in the front line probably more than any other officer in the whole Mediterranean. I definitely desire both Collins and Truscott as corps commanders and I should like to have them here at the earliest possible date. I will make available for transfer to the Mediterranean any one or two corps commanders that Devers may select, except for Gerow,47 who according to Bradley has done so much of the preliminary planning for the assault that he could not be allowed to go without prejudice to this operation.48

I have become convinced that the infantry assault in OVERLORD must be broadened and because of geographical considerations two American corps will be involved.49 I would have Gerow and Truscott lead this assault, and consequently should like to have Truscott here as quickly as possible. His three months of planning will give him a respite from the battle line while his experience and outstanding qualities of battle leadership will make him of inestimable value. A few days ago I sent an informal inquiry to Devers concerning his willingness to let Truscott come up here and while I have not received an answer to that message I am telling you my desires very frankly since the question is raised by your telegram.50

The arrival here of both Collins and Truscott and the sending to Devers of only one officer of his selection such as Woodruff, Crittenberger or Walker, would leave me with one surplus corps commander. I will be glad to have you name the additional man to be replaced.

To sum up all the above I feel immediate need for both Truscott and Collins and for an army commander. To obtain Truscott and Collins I will make available to Devers, or for other assignment by the War Department, an equal number of officers either from officers already here or yet to come.

Eisenhower to Marshall

19 January

Ref: W-9745

Yesterday I sent you a long telegram based on your R-8213. This morning I have received your number 9 which says that Devers has changed his mind. I must say it is a great disappointment to me. However, Devers still apparently wants an additional Corps Commander and since I am getting Collins I would be perfectly willing to let Crittenberger go to Africa.51

I think you might still consider the advantage of sending Truscott here in exchange for one of our Corps Commanders, which move would not only give him a rest from the battle line but would enable us to use his particular experience to the best advantage.

Marshall to Eisenhower

20 January

Ref: R-8316

General Patton is now without an assignment in the Mediterranean Theater and Devers desires orders issued for him. Do you want him sent to the U.K. now?

I considered ordering him home for a short time prior to his going to England. However, in view of the publicity given his case, his presence here, if not kept secret, might result in reopening the entire matter with vituperative discussions52 and speculations as to his future. You realize how difficult it would be to keep his presence secret.53

In accordance with your wishes as stated here, Hodges is being held in the U.S. until you call for him.

Third Army Headquarters is moving to UK. I have submitted names of Crittenberger, Woodruff, Reinhardt,54 Haislip55 and Walker to Devers for indication of his preference for extra Corps Commander. 3rd Division is set up for SHINGLE and decision must be delayed on Truscott.56

Eisenhower to Marshall

20 January

Ref: W-9777

I agree with you that Patton should not go to the United States. Although he would have been a good man for ANVIL, if he is not to be used in that capacity, he should be ordered here for duty since I need an additional Army Commander. One disadvantage to this arrangement is that Hodges will be separated from his Third Army Staff and will be presumably without a definite assignment for the next several months.

I will call for Hodges well in advance of the beginning of the operation so that he may accompany Bradley throughout and be fully ready when the time comes to employ American Army Group headquarters, to take command either of First Army or the First Army Group.57

First Thoughts on OVERLORD

Eisenhower to Marshall

22 January

Ref: W-9856

Yesterday I had a long conference with the Prime Minister, who seems fully recovered. He emphasized his anxiety to support to the limit all our activities, stating several times that the cross-channel effort represented the crisis of the European war from the viewpoint of the U.K. and the U.S. He said he was prepared to scrape the bottom of the barrel in every respect in order to increase the effectiveness of the attack, remarking that the calculations of planners who have been compelled to work within the confines of the estimated availability of resources must not be permitted to limit our strength where we can do anything better through intensification of effort or through sacrifice at other places. There is a very deep conviction here, in all circles, that we are approaching a tremendous crisis with stakes incalculable. Every man with whom I have so far dealt is definitely sober and serious, but confident of the outcome if all of us do our very best. Practically all the principal commanders and staff officers are on the ground and conferences are steadily clearing away some of our perplexing problems.

After detailed examination of the tactical plan I clearly understand Montgomery’s original objection to the narrowness of the assault. Beaches are too few and too restricted to depend upon them as avenues through which all our original build-up would have to flow.58 We must broaden out to gain quick initial success, secure more beaches for build-up and particularly to get a force at once into the Cherbourg peninsula behind the defensive barrier separating that feature from the mainland. In this way there would be a reasonable hope of gaining the port in short order. We must have this.59

Altogether we need five divisions assault loaded. This means additional assets in several lines but chiefly naval, with special emphasis on landing craft.60 The staff is preparing a detailed message to the Combined Chiefs of Staff, which will be ready for dispatch very soon.

Naturally we should do everything to preserve a strong ANVIL, with an assaulting strength of at least two divisions. I fervently hope that we can do so and still get here the minimum strength necessary to have reasonable prospects of success, even if we have to wait until the end of May, although this will cost us a month of good campaigning weather.61 These are preliminary conclusions.