Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The Falklands War, which may prove to be the last 'colonial' war that Britain ever fights, took place in 1982. Fought 8,000 miles from home soil, it cost the lives of 255 British military personnel, with many more wounded, some seriously. The war also witnessed many acts of outstanding courage by the UK Armed Forces after a strong Task Force was sent to regain the islands from the Argentine invaders. Soldiers, sailors and airmen risked, and in some cases gave, their lives for the freedom of 1,820 islanders. Lord Ashcroft, who has been fascinated by bravery since he was a young boy, has amassed several medal collections over the past four decades, including the world's largest collection of Victoria Crosses, Britain and the Commonwealth's most prestigious gallantry award. Falklands War Heroes tells the stories behind his collection of valour and service medals awarded for the Falklands War. The collection, almost certainly the largest of its kind in the world, spans all the major events of the war. This book, which contains nearly forty individual write-ups, has been written to mark the fortieth anniversary of the war. It is Lord Ashcroft's attempt to champion the outstanding bravery of our Armed Forces during an undeclared war that was fought and won over ten weeks in the most challenging conditions.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 638

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

iii

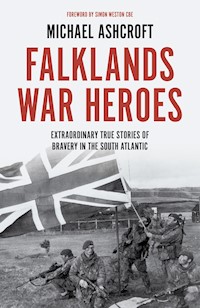

FALKLANDS WAR HEROES

EXTRAORDINARY TRUE STORIES OF BRAVERY IN THE SOUTH ATLANTIC

MICHAEL ASHCROFT

v

‘Think where man’s glory most begins and ends, and say my glory was I had such friends.’

William Butler Yeats

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is easy to know where to begin my many thank-yous. They start with my gratitude to the thirty-six men and one woman whose write-ups feature in this book. Falklands War Heroes is my tribute to their courage and service, whether they are alive or dead. My thanks in particular go to the many veterans who contributed to this book by granting me interviews so I could fully highlight their actions during the Falklands War. Marica McKay, the widow of Sergeant Ian McKay VC, helped greatly with his write-up, while Jean Messenger, the mother of the late Malcolm Messenger, also assisted me with his. I am grateful for everyone’s time and their memories, not all of them fond or easy because, as with all wars, there was a heavy price to pay even in victory.

I must single out one decorated war veteran, Gordon Mather, for special praise. He not only gave me great help with his own write-up – the longest in the book – but he also provided me with many key introductions to other veterans through his former role as chairman of the South Atlantic Medal Association, also known as SAMA 82. As a small gesture to Gordon’s generosity of spirit, I have included his favourite quote, from the Irish poet and writer W. B. Yeats, at the start of this book.

Inevitably, especially after the passing of nearly four decades, some of the former service personnel remember the same events slightly differently, so it is important to stress that this book is true to their individual memories. In some cases, where recollections were xdistinctly hazy, I have relied on individuals’ accounts of events from nearly forty years ago, including those given to other authors, rather than trying to make the veterans recall tiny details from so long ago.

A number of people helped me trace former servicemen and my thanks go to Joanne Stevens of SAMA 82, Marie Hurcum of SAMA 82, Louise Dixon of Michael O’Mara Books, Pierce Noonan of Dix Noonan Webb (DNW), Marcus Budgen of Spink, Richard Black of the London Medal Company, Matthew Richardson, Randall Nicol, Stuart Trebble, Brad Porritt and Andy Haslam.

I am grateful to David Erskine-Hill, the curator of my medal collection, for coming up with the idea for this book and for helping to collate the information needed for it. Some time ago, David realised that my Falklands War medal collection had become so formidable that, on the eve of the fortieth anniversary of the war, it should be recorded in a book.

A big thank-you, as always, to Angela Entwistle, my corporate communications director, and her team for their help in promoting this project and for arranging the book launch during the challenges presented by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Once again, I have to thank my publisher, Biteback, for their great assistance in enabling me to bring my passion for gallantry to a wider audience. Remarkably, this is my seventh book in the ‘Heroes’ series. James Stephens, Olivia Beattie and their team continue to be a delight to deal with.

Two respected medal experts, Pierce Noonan and Richard Black, have generously provided me with help and advice. In particular, as with David Erskine-Hill, they read and corrected the original draft of this book. I should, however, stress that any errors (sadly inevitable in a project of this size) are entirely down to me. Inevitably, too, different sources give contrasting figures for things like the number of casualties in a battle, and I have simply tried to go with the most authoritative source, or sources, when such totals differ.xi

Several auction houses and their staff have provided write-ups and other documentation relating to many of the medal groups featured in Falklands War Heroes. My apologies if I have missed anyone off the list, but the auction houses that have assisted include Bonhams, DNW, Morton & Eden and Spink, while others came through private purchases, including those arranged through the London Medal Company.

A large number of publishers and authors have kindly allowed me to reproduce parts of their work in this volume. All of these are listed in a comprehensive bibliography at the back of this book. My thanks to one and all for this gift.

I have also benefited from a mine of useful information on various websites, particularly www.paradata.org.uk, which champions the brave actions of the Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces.

Good photographs are vital for a book of this nature. My thanks go to Jane Sherwood, the news editor, EMEA (Europe, Middle East and Africa) at Getty Images, for her thorough picture research. I am also grateful to Christopher Cox, a freelance photographer, who photographed both my medal groups and some of the medal recipients for Falklands War Heroes.

Rebecca Maciejewska, the chief executive and secretary of the Victoria Cross and George Cross Association, was typically helpful in assisting me with this book, particularly in relation to the write-up on Sergeant Ian McKay VC.

Last but certainly not least, I am hugely grateful to Simon Weston for writing the foreword to this book. If one man represents the courage of our servicemen and women in the Falklands nearly forty years ago, then surely it is Simon. This is also an appropriate time to thank him, on behalf of so many good causes, for all the incredible charity work he has done over the past four decades – actions that rightly earned him an OBE, and later a CBE. I feel privileged that Simon should put his name to this book.

xii

Simon Weston CBE © Lord Ashcroft

FOREWORD

BY SIMON WESTON CBE

It is incredible to think that nearly forty years have passed since the Falklands War. The conflict between the United Kingdom and Argentina not only ended many young lives; it also changed several more for ever, my own included. I received 46 per cent burns to my body when the troop ship RFA Sir Galahad was bombed and destroyed by enemy aircraft while anchored in the inappropriately named (for me, at least) Port Pleasant, off the Falkland Islands, on 8 June 1982. I was the worst injured man on the ship, the worst injured serviceman to make it home alive, and I spent the best part of five years in hospital undergoing more than ninety operations.

People have repeatedly said that I was unlucky, but forty-eight men who died on my ship would have loved to have had my bad luck – they would have loved to have had the problems I faced as I recovered from my injuries. When I went to war, I was a carefree twenty-year-old lad who was proud to have served in the Welsh Guards since I was sixteen and happy to have played prop forward for more rugby teams than I can remember. However, that all ended on the fateful day when our ship was bombed and the resulting explosions turned it into a giant fireball. My physical appearance changed at a stroke, but it took years for me to adapt mentally to the new, reconstructed Simon Weston that I am today: xiva former soldier, a wartime survivor, a charity worker and, some say, with great generosity of spirit, an inspiration to others.

I am delighted that Lord Ashcroft, who has championed bravery for the past fifteen years, has chosen to mark the fortieth anniversary of the Falklands War by writing a book that highlights the gallantry of so many British servicemen and women – both those who gave their lives during the 1982 conflict and those who survived.

I have long been an admirer of Lord Ashcroft’s work in the areas of valour and the military. He has built up four major collections of gallantry medals, including the largest collection of Victoria Crosses (VCs) in the world. He has supported countless military charities, including making a donation of £1 million to the £7 million Bomber Command Memorial that was unveiled by Her Majesty the Queen in 2012.

Furthermore, Falklands War Heroes is the seventh book by Lord Ashcroft in his ‘Heroes’ series, and it does exactly what it says on the tin: it tells the stories of bravery during the ten-week war through the incredible medal collection he has amassed over the past four decades. This book will bring courageous deeds to a global audience; each write-up has been diligently researched and each story is carefully told. Furthermore, every penny of the author’s royalties will be donated to military charities.

I commend Lord Ashcroft for penning an inspirational book about men and women whose valour deserves to be championed for many decades to come. These are heroes of the Falklands War – heroes of my time – and I salute the gallantry and service of each and every one of them.

AUTHOR’S ROYALTIES

Lord Ashcroft is donating all author’s royalties from Falklands War Heroes to military charities.

LORD ASHCROFT AND BRAVERY

All the write-ups in this book are based on medal groups collected by Lord Ashcroft KCMG PC.

Lord Ashcroft also owns substantial collections of Special Forces gallantry decorations, gallantry medals for bravery in the air and some George Crosses (GCs).

His collection of VCs and GCs is on display in the Lord Ashcroft Gallery at the Imperial War Museum, London, along with VCs and GCs owned by, or in the care of, the museum.

For more information visit:

www.iwm.org.uk/heroes

For more information on Lord Ashcroft’s books on bravery visit:

www.VictoriaCrossHeroes.com

www.SpecialForcesHeroes.com

www.GeorgeCrossHeroes.com

www.HeroesOfTheSkies.com

www.SpecialOpsHeroes.com

www.VictoriaCrossHeroes2.com

For more information on Lord Ashcroft’s VC collection visit:

www.LordAshcroftMedals.com

For more information on Lord Ashcroft’s work on bravery visit:

www.LordAshcroftOnBravery.com

For more information on his general work visit:

www.LordAshcroft.com

Follow him on Twitter and Facebook:

@LordAshcroft

PREFACE

The Falklands War was an extraordinary conflict in many ways. It could easily prove to be the last colonial war that Britain ever fights. Whether or not that is the case, it is remarkable that Britain sent a force of some 20,000 men to fight for a small cluster of islands 8,000 miles away that were home to only 1,820 people – and 400,000 sheep.

This book has been published to mark the fortieth anniversary of the Falklands War. Many books have already been written about the war, all of them offering some insight – large or small – into the events in the South Atlantic during ten weeks from early April to mid-June 1982.

Between 2 April, when Argentina invaded the Falklands, and 14 June, when Argentina unconditionally surrendered and returned the islands to British control, 255 British military personnel, 649 Argentine military personnel and three Falkland Islanders died as a result of the hostilities. In all, 907 lives were lost, while 2,432 men were wounded in battle and many were left scarred, physically and mentally, by their experiences in fighting for islands that covered an area of some 4,700 square miles.

This book is not an attempt to shed new light on some of the biggest controversies surrounding the war. For example, should it have been avoided in the first place? Should Britain have strengthened the defences on the Falkland Islands as tensions grew? Did we really need to resort to fighting? Should we have attacked the xxArgentine cruiser the General Belgrano? Was the battle for Goose Green fought too recklessly? Should we have fought the war differently? And so on. Indeed, most of these controversies have been addressed extensively over the past four decades.

Quite simply, this was a war that Britain fought – and won. Almost forty years on, this book seeks to highlight the courage of many of those who risked, and in some cases gave, their lives for the rights of those men, women and children on the Falkland Islands to continue to live there free of Argentine control. This is a book crammed full of stories of derring-do, in some cases what I call cold or premeditated courage, in other cases spur-of-the-moment gallantry. The common thread that runs through the book is my admiration for the valour of our servicemen fighting a difficult war so far from their homeland. It should not be forgotten, however, that women played an important role in the war too, and one of those heroines, a nurse serving on the hospital ship SS Uganda, features as a write-up in this book.

I am often described as a military historian, but I see myself much more as a champion of bravery and a storyteller. This is my seventh book in the ‘Heroes’ series, and like most of the previous ones it is based on one of my many collections of gallantry and service medals – this one entirely centred on the Falklands War. What makes this collection so exceptional is that the medals cover virtually all the key events that took place in the war: on land, at sea and in the air. The medals also span the full length of the war: from shortly after the conflict started, via all the major battles that were fought and up until it was eventually brought to a close.

INTRODUCTION: THE BUILD-UP TO WAR

The Falkland Islands is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean made up of East Falkland, West Falkland and some 776 smaller islands. Altogether, they form a land mass of some 4,700 square miles. The islands lie approximately 300 miles off South America’s Patagonia coast.

The Falkland Islands is one of fourteen British Overseas Territories, which means it is self-governed but its residents rely on the British government for their defence and their foreign policy. Over the centuries, the islands were ‘discovered’ and exploited by colonialists. At various times, there have been British, French, Spanish and Argentine settlements on the islands.

Britain reasserted its rule over the Falklands in 1833, but since then Argentina has made numerous claims to the islands. These claims were voiced louder during the 1960s, especially after the United Nations passed Resolution 2065 calling on both countries to conduct bilateral negotiations to reach a peaceful settlement of the dispute. In the 1970s, tensions simmered after the Falkland Islanders made it clear that they wished to remain British.

In 1981, Argentina was ruled by a military junta that included army Commander General Leopoldo Galtieri. During that year, Argentina’s previously fragile relationship with America improved, and Galtieri visited Washington before ousting Roberto Viola as President in December 1981.xxii

Galtieri became convinced that seizing ‘Las Malvinas’, as the Falklands are known in Argentina, would help unite the country and increase his personal popularity. Within a short time of becoming President, he was exploring how to invade the islands using his country’s navy and, at the same time, assessing the likely response of Britain and other countries to such an act of aggression.

In early 1982, tensions rose still further, but in the UK Lord Carrington, the Foreign Secretary who was eventually to resign his post three days after the start of war on 5 April, and Richard Luce, the minister responsible for the Falklands, did not believe an invasion was imminent. With government spending under careful scrutiny, they did not see the need to send Royal Navy ships to the South Atlantic to reinforce HMS Endurance, an ice-patrol vessel already in the area but which was due for imminent decommissioning.

On 19 March 1982, a group of civilian scrap-metal workers arrived illegally on South Georgia, another British territory in the South Atlantic, and hoisted the Argentine flag. Their arrival at Leith Harbour alerted a British Antarctic Survey (BAS) team, the only British presence on the island, which, in turn, sent messages to London and to Rex Hunt, the Governor of the Falklands. At the time, South Georgia was run as a dependency of the Falklands.

At the request of the British, the Argentine flag was eventually lowered, but when diplomatic niceties were ignored, Hunt, in consultation with the British government, despatched Endurance from Port Stanley, the capital of the Falklands, to South Georgia with a detachment of twenty-two Royal Marines. Endurance left on 21 March and arrived off the BAS station at Grytviken, South Georgia, three days later.

On 26 March, the Argentine junta apparently decided to bring forward their plan to invade the Falklands, previously intended for much later in the year when they knew Endurance would be out of the area. With the situation escalating, the British government xxiiidecided on 29 March to send two nuclear submarines to the South Atlantic.

By 1 April, appropriately enough April Fool’s Day, Hunt summoned two senior Royal Marine officers to Government House and declared, ‘It looks as if the buggers mean it.’ Later that evening, having made some very basic plans to patrol and defend key targets, the Governor made a radio broadcast to the islanders, saying, ‘There is mounting evidence the Argentine Armed Forces are preparing to invade the Falklands.’ Having deployed his small force of Marines on the outskirts of Port Stanley with orders to resist an attack, Hunt declared a State of Emergency in the early hours of 2 April.

Minutes later, Argentine commandos landed on the Falklands – at Mullet Creek, 3 miles south of Port Stanley. At 6 a.m., they launched an attack on the barracks at Moody Brook, employing phosphorus grenades and automatic fire against a non-existent force – fortunately, the Marines had left the previous day.

As the Argentine forces advanced on Government House, they were briefly held back by the small force of Marines. During a two-hour gun battle, at least two Argentine soldiers were killed. However, by 8 a.m., despite one of their landing craft being hit by an anti-tank weapon, the Argentine reinforcements streamed into Port Stanley. By 8.30 a.m., and by that point cut off from communications with London, Hunt had surrendered. The British had suffered no casualties, but the Marines had the indignity of being photographed face down on the ground. Hunt, meanwhile, was taken by taxi to the airport and flown by an Argentine Hercules aircraft to Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay. Argentina was firmly in control of the Falkland Islands – but for how long?

CHAPTER 1

OPENING SHOTS

South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, like its better-known ‘neighbour’ the Falkland Islands, is a British Overseas Territory in the South Atlantic Ocean. The islands are remote and inhospitable. The largest island, South Georgia, is just over 100 miles long and 22 miles wide. The chain of smaller islands 430 miles to the south-east of South Georgia is known as the South Sandwich Islands. The area of the whole territory is just over 1,500 square miles, and the Falkland Islands lie some 810 miles west of its nearest point.

At any one time, there is a very small permanent population on South Georgia and no permanent population on the South Sandwich Islands. There are no scheduled flights or ferries to the territory, although cruise ships do sometimes stop to allow their passengers to take a look at the islands, particularly since the dramatic events of 1982.

As with the Falkland Islands, the rights to South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands have long been disputed. The UK claimed sovereignty over South Georgia in 1775 and over the South Sandwich Islands in 1908. However, Argentina claimed South Georgia in 1927 and claimed the South Sandwich Islands in 1938. In the build-up to the Falklands War, South Georgia was governed as part of the Falkland Islands Dependencies (although this came to an end in 1985, when South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands became a separate territory).

The troubles in the South Atlantic began on 19 March 1982, when a group of civilian scrap-metal workers arrived at Leith Harbour on board the transport ship ARA Bahía Buen Suceso. The group did not 2possess the required landing clearance and then raised the Argentine flag. It later emerged that the scrap workers had been infiltrated by Argentine Marines posing as scientists.

The only British presence at Leith on 19 March was a British Antarctic Survey (BAS) team, whose leader, Trefor Edwards, handed a message from London to the Commander of the Argentine ship, Captain Briatore, ordering the removal of the Argentine flag and the departure of the party. It was also demanded that the Argentine crew report to the top BAS Commander in Grytviken, Steve Martin.

Initially, Briatore replied that the mission had the approval of the British Embassy in Buenos Aires – a clear lie. The Argentine Captain eventually ordered the lowering of the flag but failed to report to Grytviken. These events prompted the BAS Commander to send a message to Rex Hunt, the Governor of the Falkland Islands. After consulting with London, Hunt was instructed to despatch HMS Endurance to South Georgia with a detachment of twenty-two Marines. The Marines landed on South Georgia on 31 March.

Until this point, Endurance and Bahía Paraíso, an Argentine naval ship, played a game of cat and mouse around South Georgia, but then they lost track of each other. And as March gave way to April, matters took a sinister turn…

KEITH PAUL MILLS

Service: Royal Marines

Final Rank: Captain

FALKANDS WAR DECORATION / DISTINCTION:

DISTINGUISHED SERVICE CROSS (DSC)

DATE OF BRAVERY: 3 APRIL 1982

GAZETTED: 4 JUNE 1982

Cometh the hour, cometh the man. Keith Paul Mills was a 22-year-old Lieutenant in the Royal Marines when he faced the greatest 3challenge of his life: how to defend a remote British outpost from a much larger invading force. He could not be reckless with the lives of his men, for whom he had a duty of care. For his actions back in early April 1982, he would be decorated with the DSC and feted back home as a war hero.

Mills was born on 5 June 1959 in Abingdon, Berkshire. The middle of three children and the son of an engineer, Mills was just four when his family moved to Harlech, in the north Wales county of Gwynedd, due to his father’s work in the nuclear power industry. Later, they moved to nearby Anglesey, where Mills spent the rest of his childhood and was educated at his local primary school and Syr Thomas Jones secondary school, both in Amlwch, the most northerly town in Wales. At his secondary school, he became the first-ever English head boy.

After leaving school at eighteen, he decided not to become an engineer as his father had hoped, giving up the offer of a place at the University of Liverpool to read electronics. Instead, he decided to join the Royal Marines, learning in May 1978 that he had been accepted for officer training at Lympstone, Devon, starting in September of that year. Even before joining the Marines as a Second Lieutenant, Mills was a talented sportsman – a black belt in judo and a keen mountaineer – and he was looking for a job that would challenge him physically and mentally.

On completing his course, Mills was appointed to 41 Commando as a troop Commander, still in the rank of Second Lieutenant. During this period and aged just nineteen, he qualified as a jungle warfare instructor in Brunei. The unit then completed a tour of duty with the United Nations in Cyprus and an operational tour in South Armagh, Northern Ireland, during the height of The Troubles. Next, he was appointed to 45 Commando as a company second-in-command, and he completed Arctic warfare training in Norway. In 1981, he was appointed to the Antarctic patrol ship HMS Endurance. 4

As detailed in the introduction to this chapter, he and his men had been despatched to South Georgia from the Falkland Islands to eject the scrap-metal dealers who had illegally arrived and put up the Argentine flag on 19 March. Again as detailed in the introduction, the situation had become more serious as March turned to April. In fact, when Mills and his men had landed on South Georgia from Endurance on 31 March, even then a full-scale invasion of the Falklands seemed an unlikely scenario to the British. Both Captain Nick Barker, in command of Endurance, and Mills thought the crisis would probably ‘blow over’ in a few days. Before dropping off the Royal Marine detachment, Barker told Mills to defend the British scientists but not to alarm them by saying that they were in any danger. Barker also told Mills that there should be no radio communication between them, as that could indicate the position of Endurance to the enemy. The rules of engagement for Mills and his men were that they could only open fire in self-defence or in the process of saving a life. The party went ashore with 20,000 rounds of ammunition – just in case.

We now know that the Argentine force planned to invade South Georgia on 2 April but were put off by the terrible weather, including a force 12 gale. However, the Argentine ship Bahía Paraíso had entered the main bay at South Georgia that day and had sent a radio communication to the British base saying it would return the next day with a ‘very important message’. Mills and his men were, by this point, aware of the invasion of the Falkland Islands, and so they started to ‘dig in’ and prepare to defend the island. Mills also decided to break radio silence with Endurance, radioing, ‘The Argentinians have made contact with us and will do so again tomorrow morning. What are our instructions?’ Much later in the day, the reply came back from Endurance: ‘When the Argentinians make contact with you, you are not to co-operate.’ However, Mills was understandably left puzzled by just how much of a fight that 5meant he should put up. He replied, ‘Your last message is ambiguous. Please clarify.’

Very early the next day, Endurance sent Mills a further message: ‘When asked to surrender, you are not to do so.’ When Mills relayed this message to his men, there were whoops and hollers of delight; they were up for a firefight, but until this moment they had feared that they would have to surrender without any resistance. Half an hour later, however, yet another message came through from Endurance: ‘The OCRM [Officer in Charge Royal Marines] is not, repeat not, to take any action that would endanger life.’ Mills was thoroughly confused and confided the final message only to Sergeant Major Peter Leach, his second-in-command. Mills told Leach that he had decided not to pass this message on to the rest of the men in case it ‘muddied the waters’ over what they could and could not do as and when the enemy arrived to take the island. By this point, too, explosives had been placed on the main jetty, ready to be detonated if the enemy invaded.

So, at dawn on 3 April 1982, Mills was in charge of a force of twenty-two Royal Marines, including himself, defending South Georgia and thirteen British scientists. The situation facing him could hardly have been more challenging. The previous day, an Argentine force had invaded the Falkland Islands, forcing Rex Hunt to surrender after a short-lived battle. Meanwhile, Endurance was at sea midway between the Falklands and South Georgia, making its way to the latter. Captain Nick Barker was, in turn, in touch with London and getting increasingly frustrated by orders not to try to engage the enemy.

At 10.30 a.m. on 3 April, Captain César Trombetta, on board the Bahía Paraíso and leading the Argentine force in the area, radioed over the Channel 16 international frequency to the South Georgia garrison, saying, ‘Following our successful operation in the Malvinas Islands, the ex-Governor has surrendered the Islands and 6dependencies to Argentina. We suggest you adopt a similar course of action to prevent any loss of life. If so, all British troops and government personnel will be repatriated to the UK unharmed.’

Mills asked for ‘some time to clarify the situation’ – i.e. to consider his response and to radio the Endurance for guidance. He had hoped for several hours’ grace but was told he had only ‘five minutes’ to consider his response. In his book, Captain Barker wrote of this moment: ‘3 April was the day when the feeling of impotence hit hardest. I hated what I had to do only slightly less than I despised those who had brought about this situation.’

Meanwhile Mills, after his five minutes of thought, radioed Bahía Paraíso to say, ‘I am the British Commander of the military troops stationed on South Georgia. Do not make any attempt to land until we have clarified the situation with our superiors. Any attempt to land will be met with force.’

Later that morning, Barker lost radio contact with South Georgia, writing long afterwards:

We knew that the battle had begun … We were most fearful for Keith and our Marines. The situation they faced was untenable. Their lives depended on an honourable adversary and the common sense to know when to admit defeat. When you join the armed services you accept the risks. But you do not expect to fight, and perhaps die, on some Godforsaken windswept mountainside just about as far from home as you can get. At this point South Georgia seemed unimportant, an irrelevance. What could Argentina do with it anyway?

The Marines were ‘dug in’ in a position about 100 metres from the shore in a sheltered bay, with a Union flag fluttering nearby. They had placed mines and improvised explosive devices in front of the position where they anticipated the enemy would land. Mills had 7intended to give them a ‘bloody nose’ and then withdraw into the mountains, where his men had some basic supplies.

The first the Marines saw of the invading force was the corvette Guerrico rounding a point and coming into a cove close to the BAS base. She was supported by an Alouette helicopter hovering above. Initially, Mills marched down to the jetty at King Edward Point with the intention of talking to the Argentine landing party. Instead, the helicopter landed and dropped some eight enemy Marines close by, one of whom raised his rifle in Mills’s direction. Mills decided there would be no opportunity to talk, and instead he retreated.

Next, a Puma helicopter from Bahía Paraíso attempted to land on the foreshore. Mills ordered his men to commence firing and more than 500 rounds of small-arms fire hit the helicopter from a range of under 100 metres. Trailing smoke, the aircraft pulled away and limped some 1,200 metres to the other side of the bay, where it crash-landed. Next on the scene was another helicopter, again an Alouette, and this aircraft was also hit by British fire and crashed.

Guerrico began blasting away with 40mm guns from the aft-end and a 100mm gun from the bow. The British expected her to stop out of their range and then fire at them from a safe distance, but instead Guerrico carried on until she was only 500 metres from the British force. In his official report of the incident, a copy of which I have obtained, Mills later wrote:

I ordered my men to open fire. The corvette was committed to entering the bay and could not turn around. The first 84mm round fired at the ship landed approximately 10 metres short of its target. The round did not detonate on impact with the water, but did detonate on impact with the ship below the water line. The ship was also hit by a 66mm round behind the front 100mm turret. The ship was also engaged by heavy machine gun and rifle fire.

8Mills continued:

The ship then moved right into the bay, about turned, and headed out to sea again at full speed. We engaged the corvette for a second time scoring anti-tank rocket hits on the Exocet and to the main upper deck superstructure. Again she was engaged by heavy machine gun and rifle fire. I was later informed by an Argentine marine officer that we had scored a total of 1,275 hits on the corvette, and had we hit her again below the water line she would surely have sunk.

The corvette then made its way to a position about 3,000 metres away and started to shell our position with her 100mm main armament. What I did not know at the time was that the elevation control on the gun had been destroyed and the ship had to manoeuvre its own position to enable the shells to land accurately on our position. This shelling continued for a period of about twenty minutes. During this time we were continually engaged by heavy and accurate fire from the other Argentine positions.

When the shelling stopped there seemed to be a temporary ceasefire. It was then I realised that a withdrawal for us would be almost impossible as the Argentine troops that had landed earlier on the far side of the bay had moved round to cut off our withdrawal. We had by this stage already sustained one casualty, and I realised that we would sustain many more had we waited until the hours of darkness before attempting a withdrawal. A withdrawal in daylight conditions would have been impossible. Having already achieved our aim of forcing the Argentines to use military force I realised we could achieve no more, and it was at this stage I decided to surrender to the Argentine forces. We were also in the fortunate position at this stage of having pinned a group of Argentine marines down close to our position.

As we had not planned to surrender, we had no white flag, and 9therefore had to improvise using a green anorak with white lining. On initially waving this article of clothing [at the top of a rifle] the Argentines engaged it with heavy fire. I then waved it again and this time it was not engaged. I realised that I would have to move forward from my position to negotiate with the Argentines as it was unlikely they were going to come to me. I slowly stood up [from the safety of the trench], and remarkably I was not shot. I then moved forward to the Argentine position in the base and was met by an Argentine marine officer. I informed him that his position was desperate as was ours, and unless we ceased firing then he and his men in the position in the base would surely die. We had achieved our aim and if we were to be guaranteed good treatment we would lay down our arms sparing the lives of many of his men who would surely have died had he taken our position by force. The Argentine officer agreed saying that it was a very sensible decision and that he would guarantee good treatment for my men.

After more than two hours of intense fighting, the battle for South Georgia was over. It is believed that the twenty-two Royal Marines faced an overall invasion force of some 300 enemy servicemen. The sole British casualty was a corporal shot twice in one arm. The number of enemy casualties is not known, but it is likely there was a total of around twenty dead and wounded.

Mills and his men assembled on the beach. Along with the rounded-up thirteen scientists, the British party gathered on Bahía Paraíso. In an interview at his Devon home, Mills told me that the Argentines had initially been ‘twitchy’ immediately after the British had surrendered. They could not believe they were facing a force of just twenty-two men and feared they were about to be ambushed.

After a while, they accepted it was just twenty-two of us. Even 10when we were unarmed, they were still very wary of us, while our guys were a bit worried that we still might all get shot in cold blood. It was all a bit tense. I had to tell the Argentines that we had ‘wired up’ the jetty and other areas. I didn’t want them blowing themselves up now that we were all prisoners of war.

As for Captain Barker on Endurance, he arrived on the scene hours later, but by then he could not provide support, later writing, ‘It was to our huge regret that all this happened as we were heading east round the southern tip of South Georgia. I had every intention of bringing helicopter support to our Marines by mid-afternoon. We were too late.’

Back home in Britain, the media seized upon Mills’s bravery: it was the first bit of ‘good news’ to come from the South Atlantic. Mills’s last stand was likened to the famous defence of Rorke’s Drift in 1879 during the Anglo-Zulu War, when a small group of British soldiers held out against a much larger force of marauding Zulus. Newspaper headlines on 5 April 1982 were full of his bravery from two days earlier. The front page of the Daily Star carried the huge headline ‘Keith Mills, hero’, alongside a smaller headline that read: ‘Marine who showed Whitehall that the British fighting spirit is still alive’.

After their negotiated surrender, Mills and his men plus the scientists embarked on a voyage to Puerto Belgrano, Argentina, which took a total of eleven days, part of it spent circling the Argentine coast while the enemy decided what to do with its prisoners. Once they landed, the Marines were kept at the port for four more days and were questioned about the conduct of the Argentine forces in South Georgia by some sort of board of inquiry.

Mills became emotional with sheer pride when he told me how a senior Argentine officer, General Carlos Büsser, had insisted on meeting all twenty-two Royal Marines in person. The General told 11Mills: ‘I have come here today because I have been in Buenos Aires listening to the stories of the defence by British Marines of South Georgia. I am a Marine and I decided that I had to come and meet these men.’ Mills continues,

With that, the General went along the line and saluted each of my men, shook their hands and said, ‘If Argentine marines were the same as British marines, we would conquer the world. If there is anything you want, let me know and you will have it.’ We made a short list that ended ‘Twenty-two one-way tickets to London and twenty-two women.’ Büsser said: ‘You can have everything on the list except the women and the one-way tickets home you will have to wait for.’ Yet the next day we flew out of Argentina.

On 17 April, the British Marines were flown to Montevideo, where they were looked after by the British Consulate. On the morning of 19 April, they were flown back to England in an RAF VC10, landing at RAF Brize Norton, Oxfordshire, on the morning of 20 April. Mills was soon reunited with his then girlfriend, Liz Stananought, later to become his wife.

Mills was awarded the DSC on 4 June 1982, and his citation read:

Lieutenant Mills was the Commanding Officer of a 22-man Royal Marines contingent despatched to South Georgia on 31st March 1982 to monitor the activities of a group of Argentines illegally landed on the island and to protect a British Antarctic Survey Team based there. On 3rd April 1982 a major Argentine assault began and, following his unsuccessful attempts to forestall the attack by negotiation, Lieutenant Mills conducted a valiant defence in the face of overwhelming odds. In spite of the fact that his unit was impossibly outnumbered, extensive damage was inflicted on the 12Argentine corvette Guerrico, one helicopter was shot down and another damaged. Only when the detachment was completely surrounded, and it was obvious that further resistance would serve no purpose, did he order a ceasefire, placing himself at great personal risk to convey this fact to the invading forces. Lieutenant Mills’ resolute leadership during this action reflected the finest traditions of the Corps.

On the same day, Sergeant Peter Leach was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) for his gallantry during the same action.

In a typed letter dated 7 June 1982, Admiral Sir Desmond Cassidi, the Second Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Personnel, wrote to Mills saying, ‘Many congratulations on your award of the DSC for the part you played in the defence of South Georgia. As the citation for your award states, your resolute leadership during this action reflected the finest traditions of the Corps. Well done.’

Captain Barker later wrote a hand-written and ‘informal’ letter to Mills’s father, Alan, dated 1 August 1982, in which he congratulated him on his son’s bravery:

This was a magnificent action and he richly deserves his D.S.C. There has been a great deal of bravery during this short, sharp war, but Keith set the pace, set the example and gave a very special sense of pride back to the country as a whole. We are all proud of him…

I have also obtained a copy of an internal report that summarises Mills’s work between June 1981 to September 1982, which included the period of the Falklands War. It read:

There is usually fun, quick wit and coarse humour when Keith Mills is about. He is irrepressible, enthusiastic to a degree about 13most things, killing Argentines in particular, and a very good man to have in a ‘tight corner’. He is very fit and has boundless energy and a good brain once he has it pointed in the right direction.

Although a carefree, somewhat wild, young officer, he proved to be calm and extremely courageous during the First Battle of Grytviken, his DSC was very well deserved indeed and his maturity when the ‘chips were down’ was outstanding.

I have thoroughly enjoyed having him on board, he has led his men very well, he has accepted many new habits with grace and should do well in future appointments.

After the war ended, a mountain on South Georgia was named ‘Mills Peak’ in the young officer’s honour. ‘A lot of people are fortunate enough to be awarded gallantry medals, but to have a landmark named after you is quite something. I was very touched,’ Mills told me.

After the Falklands War, Mills’s roles included a second UN tour of Cyprus with 40 Commando, another operational tour of Northern Ireland and training duties. He also represented the Corps, the Royal Navy and the Combined Services at alpine skiing. He was promoted to Captain in 1989, was Adjutant at the Royal Marines Depot in Deal, Kent, at the time when the IRA bombed the barracks, killing eleven Marines from the Royal Marines School of Music and leaving another twenty-one wounded. From 1992 to 1995, he was involved in an officer exchange role with the Royal Netherlands Marine Corps, and in 1995, he was appointed as a liaison officer in Bosnia and Croatia at the height of the Balkan War. Mills left the Marines in the rank of Captain on 4 July 1996. By that point, he and his wife, who were married in 1986, had two children.

A final internal assessment of Mills’s work, written in September 1995 just months before he left the Royal Marines, stated, ‘Mills is a 14muscular, fit and dynamic officer brimming over with enthusiasm and energy. Although due to leave the Service shortly on voluntary redundancy, he has not let this intrude on his performance … His decision to leave the Corps is a sad one, if fully understandable.’

In 2007, Mills and his wife were invited back by the Commissioner of South Georgia to unveil a plaque as part of the commemorations of the war a quarter of a century on. Before leaving for their adventure, he said, ‘I haven’t been back in twenty-five years. I’m quite excited. I’ve heard it’s changed a bit.’ During his visit, Mills flew over the peak named after him in a helicopter, but it was considered too unsafe to land and walk on it.

After leaving the Armed Forces, Mills started a business developing and running care homes for the elderly in east Devon, where he continues to live. He remains as managing director of Doveleigh Care Ltd, which has three award-winning care homes; he has held the position for twenty-five years.

CHAPTER 2

THE WAR AT SEA

On 5 April 1982, just three days after Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands, the British Armed Forces were ordered to sail to the South Atlantic fully 8,000 miles away. On 7 April, the UK announced, rather ambitiously, its intention to impose a 200-mile exclusion zone around the Falkland Islands. It did so knowing that it would be weeks before it could even try to enforce what became known as the ‘TEZ’ (Total Exclusion Zone), and even then, their task might prove impossible.

In the days just before the invasion, and with the Argentine fleet en route to the Falklands, Margaret Thatcher had discussed the prospect of an Argentine attack with her defence chiefs, including Admiral Sir Henry Leach, the First Sea Lord. The Prime Minister had asked him bluntly: ‘First Sea Lord, if the invasion happens, precisely what can we do?’ Leach’s response was calm and considered: ‘I can put together a Task Force of destroyers, frigates, landing craft, support vessels. It will be led by the aircraft carriers HMS Hermes and HMS Invincible. It can be ready to leave in forty-eight hours.’

This is exactly what happened after the invasion. The Task Force eventually comprised 127 ships: forty-three naval vessels, twenty-two Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) ships and sixty-two merchant ships. Those ships requisitioned for war duties included the giant cruiser SS Canberra, which set sail from Southampton on 9 April with 3 Commando Brigade on board, and the ocean liner Queen Elizabeth 2, which left from Southampton on 12 May carrying the 5th Infantry Brigade. British military actions in the war were given the codename ‘Operation16Corporate’ and the Commander of the Task Force was Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse.

When the first ships in the Task Force set sail, there was still a reasonable chance that war could be avoided. However, it soon became clear that the Royal Navy and the men on its ships were sailing to war and that the challenges they faced would be formidable. With no advantage over the enemy on land or in the air, it also became clear that the Royal Navy, the senior service in the Armed Forces, would have to play a key role in the fighting. Indeed, how the navy fared was likely to decide whether the war was won or lost. At the time, the US Navy was said to have assessed the chances of the Task Force recapturing the islands as ‘a military impossibility’.

Depending on where it set off from and the size of the ship, the journey to the Falkland Islands was expected to take around three weeks. Most ships stopped off at Ascension Island – a 34-square-mile mound of volcanic rock in the South Atlantic – on the way, to pick up supplies and to prepare for what lay ahead. Meanwhile, a small force had been sent to recapture South Georgia, with the British destroyer HMS Antrim arriving off the island on 21 April. Military actions to recapture South Georgia were codenamed ‘Operation Paraquet’ (sometimes also spelt ‘Operation Paraquat’). This task was achieved on 25 April 1982, with Mrs Thatcher famously telling the nation to ‘rejoice’ at the news.

On 2 May, the day after two Vulcan bombers had attacked Stanley airfield, the first major loss of the war took place when, in what were to become highly controversial circumstances, the Argentine cruiser General Belgrano was sunk by a torpedo fired from a British submarine. The sinking led to 323 Argentines being killed, while 700 sailors survived. News of the sinking caused shock among the Task Force and the British public, and the incident became a cause célèbre for antiwar campaigners. Opponents of the sinking claimed that the Belgrano was outside the TEZ and sailing away from the conflict. British defence insisted, however, that the Task Force had the right to defend itself against any hostile vessel.17

Once the Belgrano had been sunk, and with British ships near the Falklands particularly vulnerable to attack, it was almost inevitable that Argentina would strike back fast and hard. On 4 May, HMS Sheffield was hit by an Exocet missile, which started a fire in the control room. The crew was forced to abandon ship and twenty men died. The Sheffield was the first British warship to be sunk in the conflict.

On 14–15 May, the SAS attacked Pebble Island, which could have given an early warning of the arrival of the British fleet. Three days later, the Argentine junta rejected British peace proposals, and two days after that, on 20 May, United Nations peace talks also failed, thereby ending any real hope of a diplomatic outcome to the crisis.

With a land battle now inevitable, 3,000 troops and a mass of equipment were landed at San Carlos Water, East Falkland, on 21 May, with a view to establishing a beachhead for attacks on Goose Green and Port Stanley. As the Argentine Air Force tried to prevent the landings, HMS Ardent was sunk with the loss of twenty-two crew. HMS Argonaut and HMS Antrim were also hit by bombs that failed to explode but nevertheless killed two men. In turn, thirteen Argentine aircraft were reportedly shot down.

Two days later, on 23 May, HMS Antelope was hit and later sunk after one of the bombs that had lodged in the ship exploded during bomb-disposal work. In a week of heavy British casualties at sea, HMS Coventry was bombed on 25 May, with the loss of twenty men, and on the same day the container ship Atlantic Conveyor was hit, with twelve men being killed.

In June, as the land war escalated, there were further major casualties at sea. On 8 June, as British troops were ferried from San Carlos to Bluff Cove and Fitzroy, ready for the southern offensive on Stanley, the Argentines again mounted a deadly attack. A delay in disembarking troops meant that around fifty men, most of them from the Welsh Guards, were killed by Argentine aircraft which attacked the landing ships Sir Galahad and Sir Tristram. Four days later, as the land war18reached its climax, the British destroyer HMS Glamorgan was hit by a shore-launched Exocet missile, killing a further thirteen men; another member of her crew later died of his wounds.

Falklands War Heroes does not seek to provide a definitive account of the war at sea. That role has already been fulfilled by Admiral Sir Sandy Woodward’s One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander and many other excellent books. However, this book does try to provide an insight into the bravery of some of those who served at sea, particularly their gallantry throughout the losses of some of the Royal Navy’s finest ships and most courageous men. No less brave were many soldiers from the British Army who died or displayed valour while the ship in which they were being transported came under attack.

The contribution of the Royal Navy in recapturing the Falklands was immeasurable. Woodward’s last signal to the Task Force on 4 July 1982 from HMS Hermes, then off Port Stanley, said: ‘As I haul my South Atlantic flag down, I reflect sadly on the brave lives lost, and the good ships gone, in the short time of our trial. I thank wholeheartedly each and every one of you for your gallant support, tough determination and fierce perseverance under bloody conditions. Let us all be grateful that Argentina does not breed bulldogs and, as we return severally to enjoy the blessings of our land, resolve that those left behind for ever shall not be forgotten.’

GRAHAM JOHN ROBERT LIBBY

Service: Royal Navy

Final Rank: Petty Officer

FALKLANDS WAR DECORATION / DISTINCTION:

DISTINGUISHED SERVICE MEDAL (DSM)

DATE OF BRAVERY: 25 MAY 1982

GAZETTED: 8 OCTOBER 1982

19HM submarine Conqueror is best known for sinking the Argentine cruiser General Belgrano in an incident that is still controversial nearly forty years on. Yet for crew member Petty Officer Graham Libby, his greatest test came not at the time of the sinking but less than a month later, when he showed outstanding courage as a diver to solve a major problem faced by his submarine.

Graham John Robert Libby was born on 2 December 1958 in Portsmouth, Hampshire. The son of a Royal Navy diver, he was brought up and educated in the city before leaving school at sixteen. As a boy, he had initially wanted to join the fire brigade, but he eventually enlisted in the Royal Navy instead in 1975, aged sixteen. Two years later, he transferred to the Submarine Service, and like his father before him, he became a diver.

By the spring of 1982, when war broke out, Libby had been serving in the Conqueror, arguably the most famous British submarine ever launched, for three years. Some 285ft long with a beam of 32ft, the Conqueror was ordered on 9 August 1966, just ten days after England defeated West Germany 4–2 in extra time to win the World Cup. The Conqueror was built at Cammell Laird’s Birkenhead shipyard and was launched on 28 August 1969, then finally commissioned on 9 November 1971. The Conqueror was a Churchill-class nuclear-powered submarine with a complement of more than 100 officers and crew.

By late March 1982, after completing a three-month overseas deployment, the Conqueror was back at her base of Faslane, situated on the eastern side of Gare Loch, Scotland, home to the 3rd Submarine Squadron. With the submarine in need of some repair work, her crew was given leave. However, just two days before the invasion of the Falkland Islands and with diplomatic alarm bells ringing loud and clear, the men were ordered to return to the boat – and to prepare for war. Libby was one of those on leave at his home in Portsmouth on 1 April 1982. He told Mike Rossiter, the author of the book Sink the Belgrano: 20

I had only been there a few days when there was a knock on the door and there was this policeman stood there saying, ‘You’ve been recalled. Make your way to the boat.’ It was the morning of April the first he knocked on the door, and I thought, this is a wind-up, April fool, so I phoned the boat up in Faslane, and they said, ‘Yeah, it’s true – you’re recalled.’ When I got there it was just a hive of activity. There were stores on the jetty, there was a complete new weapons load, everybody was running around, and I thought this is not a wind-up, this is not an exercise, something is going on here.

The crew received instructions to ‘store for war’, which meant taking twice the amount of provisions on board that were needed for a routine patrol. To start with, all the crew were baffled as to their destination, but it soon emerged that there was trouble brewing in the Falkland Islands. Soon, under the command of the newly appointed Commander Christopher Wreford-Brown, the Conqueror was sailing for the South Atlantic – but with many of the crew initially convinced that the dispute would be settled by diplomacy, not military conflict.

Libby was the submarine’s ‘scratcher’, the crewman responsible for the maintenance of the outer casing. Part of his role was to ensure that the capstans, winches and cables were all properly secured and that they made no noise when the boat was under way: in war, such noises could give away the submarine’s position, resulting in it being torpedoed or bombed and all lives on board being lost. Libby was also the most senior diver on board the Conqueror.

He was enthusiastic about the secret presence of fourteen Special Boat Service (SBS) men on board the submarine. The SBS – men drawn from the Royal Marines – were not as famous as their SAS cousins, but they were still respected as an elite and highly trained force. However, early on in the Conqueror’s journey to the South 21Atlantic, the Special Forces men also gave him cause for concern. In his interview with Mike Rossiter, Libby takes up the story some time after the submarine left Faslane on 4 April:

We were heading down, making good speed, when suddenly we heard this massive thumping noise. It sounded like part of the boat was rattling and we thought, ‘What the hell is that?’ You don’t like it because it means you haven’t done your job properly, or we have to surface and fix something. And we have guys on the boat that can go round with a little portable device to isolate where the sound is coming from. Because we have to fix it, you can’t make those sort of noises when you are operational, you have to be quiet. And we listened and we couldn’t pin down what it was. Eventually the noise monitors came back. The banging was the SBS guys doing their exercises in the fore part [of the submarine] where the torpedoes were stored. They were banging against the metal grating and it was being transmitted out to the ocean. It was a hell of a racket. So we had to put rubber mats down whenever they wanted to work out. But to have an SBS unit on board was unusual, and you thought, ‘What the hell’s going on?’ We knew we were going south but we didn’t know why these chaps were on board.

Libby also said that once on board, the crew tended to concentrate on the job in hand: ‘You didn’t forget your family; it’s very strange, you have your family but they’re over there in England in a box, and you very quickly come down to the only thing that matters is the submarine and the job it’s doing and your mates.’

Libby said the crew picked up snippets of information on their journey south – they crossed the equator after just over a week at sea, on 12 April – but they never got the complete picture. ‘We’d 22get told that Mrs Thatcher’s doing this and this has happened, and rules of engagement are changing. Although we were never told specifics, you know. You were kept in the picture but you were kept in the little tiny picture in the corner of a big picture.’

After nearly three weeks at sea, Conqueror was approaching South Georgia, more than 900 miles south-east of the Falklands. By this point, the British government had decided to retake South Georgia prior to mounting an attack on the Falkland Islands. However, when the assault on South Georgia was planned, no role was given to the SBS men travelling in the submarine. Conqueror resurfaced so the men could be picked up by helicopter and transferred to HMS Antrim