12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

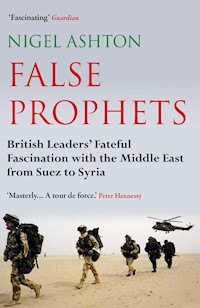

'Fascinating' Guardian, 'Book of the Day' 'A truly masterly book... A tour de force that will be read for a very long time.' Peter Hennessy Selected by the New Statesman as an essential read for 2022 Britain shaped the modern Middle East through the lines that it drew in the sand after the First World War and through the League of Nations mandates over the fledgling states that followed. Less than forty years later, the Suez crisis dealt a fatal blow to Britain's standing in the Middle East and is often represented as the final throes of British imperialism. However, as this insightful and compelling new book reveals, successive prime ministers have all sought to extend British influence in the Middle East and their actions have often led to a disastrous outcome. While Anthony Eden and Tony Blair are the two most prominent examples of prime ministers whose reputations have been ruined by their interventions in the region, they were not alone in taking significant risks in deploying British forces to the Middle East. There was an unspoken assumption that Britain could help solve its problems, even if only for the reason that British imperialism had created the problems in the first place. Drawing these threads together, Nigel Ashton explores the reasons why British leaders have been unable to resist returning to the mire of the Middle East, while highlighting the misconceptions about the region that have helped shape their interventions, and the legacy of history that has fuelled their pride and arrogance. Ultimately, he shows how their fears and insecurities made them into false prophets who conjured existential threats out of the sands of the Middle East.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Also by Nigel Ashton

King Hussein of Jordan

Kennedy, Macmillan and the Cold War

Eisenhower, Macmillan and the Problem of Nasser

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Nigel Ashton, 2022

The moral right of Nigel Ashton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Quotations from the following works are reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear: Clarissa Eden: A Memoir by Clarissa Eden, copyright © Clarissa Eden, 2007; John Major: A Political Life by Anthony Seldon, copyright © Anthony Seldon, 1997; The Macmillan Diaries: The Cabinet Years, 1950–1957 edited by Peter Catterall, copyright © The Trustees of the Harold Macmillan Book Trust, 2003; The Macmillan Diaries, Volume II: Prime Minister and After, 1957–1966 edited by Peter Catterall, copyright © The Trustees of the Harold Macmillan Book Trust, 2011.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-786-49325-5

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-786-49328-6

E-book ISBN: 978-1-786-49327-9

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Dedicated to the memory of my parents,John and Patricia Ashton

CONTENTS

Map

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Part I: The Nasser Threat

1. Anthony Eden: Suezcide of a Statesman

2. Macmillan’s Hot Pursuit of Nasser

3. Douglas-Home’s War in Yemen

Part II: War, Peace and Oil

4. A Tale of Two Kisses: Harold Wilson, George Brown and the Middle East

5. Heath’s Day of Atonement

6. Callaghan’s ‘Local Terrorist Made Good’

7. Arms and the Woman: Margaret Thatcher and the Middle East

Part III: The Iraqi Wars and Their Aftermath

8. Major’s Safe Haven

9. The Next Stage of Evil: Tony Blair and the Middle East

10. In Blair’s Shadow: Gordon Brown and the Middle East

11. Cameron and the Arab Spring

Conclusion

Endnotes

Select Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I DATE MY fascination with the Middle East back to the year 1973 when I have a strong childhood memory of watching television pictures of cheering soldiers sitting astride tanks as they drove to and from the battlefields of the October War. Equally strong is the subsequent memory of queueing for petrol in the back of my father’s car as the Arab oil embargo hit hard in Britain. It was all rather perplexing for an eight-year-old child. I would like to think I resolved then to make sense of it all by writing a book in later life, but that would be to put too firm a construction on the foundation of childhood memory. Nevertheless, what that turbulent year did underline was that one way or another Britain’s fate was bound up with events in the Middle East, a lesson which British leaders had already taken to heart.

Beyond these powerful childhood memories, the subsequent impetus to write this book was born of a certain impatience, which has nagged at me throughout my career as an historian, with the way in which Britain’s role in the Middle East has been framed. Thirty years ago, as a doctoral student I wrote a thesis challenging the notion that the Suez crisis of 1956 represented the final throes of British imperialism in the Middle East. Contemporary experience as much as historical research seemed to bear the argument out since the thesis was completed against the backdrop of another war in the region during 1990–91, with British forces joining an American-led coalition to liberate Kuwait from Iraq.

But the clearest vindication of the argument still lay in the future then. Tony Blair’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan which followed the 9/11 attacks on the United States provided the clearest demonstration of all that Britain had never really withdrawn from East of Suez or abandoned its role in the Middle East. Most fascinating of all was the way in which Blair’s framing of the wars as an existential struggle for the preservation of Western civilization mirrored the warnings delivered by Anthony Eden half a century earlier. In this book I have set out to connect up Eden and Blair by looking at the continuing fascination exerted by the Middle East over the intervening and succeeding tenants of 10 Downing Street. As I indicate in the conclusion, I also see the book in part as an antidote to the almost pathological preoccupation with Europe which has haunted British politics over recent decades. We should not forget that it was the Middle East which was, in fact, the recurring focus of British leaders’ fears, and the main object of their military interventions, throughout this period.

In researching and writing the book I have incurred many debts. I am grateful to the archivists at the numerous libraries where I have worked for their curation of the documents which are the essential raw materials of historical writing. I am also grateful to my colleagues in the International History Department at the LSE for the intellectual stimulation they have provided over the course of the past two decades. My agent, Natasha Fairweather, has offered invaluable assistance, not least in placing this manuscript with Atlantic Books. At Atlantic, I am most grateful to my editor, James Nightingale, for his insight and understanding throughout the publication process.

The greatest debts of course are always personal. My wife, Danielle, and daughters, Isabelle and Sophie, have offered me unstinting love and support throughout the research and writing process. Meanwhile, my parents, who both passed away during the course of the writing of the book, always understood the value of education. It is to their memory that I dedicate this book.

INTRODUCTION

IT WAS THE moment Gamal Abdel Nasser found his voice. Standing before a huge crowd assembled in Alexandria’s Manshiya Square on 26 July 1956, the Egyptian President spoke, not in the stiff and formal Arabic of his earlier speeches, but in the language of the masses. The tale he told was one of sacrifice to end injustice, of the triumph of the Arab spirit over the schemes of the British occupiers. As he spoke of his quest to free Egypt from grinding poverty and oppression through the construction of a mighty dam on the Nile at Aswan, an elite band of soldiers led by Major Mahmoud Younes lay in wait outside the offices of that hated symbol of Western domination – the Suez Canal Company. And then, in the midst of an otherwise mundane passage in the speech about Nasser’s meetings with the President of the World Bank, Eugene Black, came the code word: ‘I started to look at Mr Black, who was sitting on a chair,’ Nasser observed, ‘and I saw him in my imagination as Ferdinand de Lesseps.’ As he uttered the name of the notorious French architect of the Canal, Major Younes and his men sprang into action, storming the Company’s offices. The Suez Canal now belonged to Egypt.

Even this moment of high drama was not without its element of bathos. Worried that his men might have missed the code word, Nasser went on to repeat de Lesseps’s name no fewer than fourteen times in his speech. Even as the cheering crowds drained from the square at the end of the rally, an observer from the United States embassy noted that something symbolic had been left behind. Standing forlornly amidst the detritus of the crowd was a float in rather questionable taste, depicting the Sphinx swallowing a British soldier with the Union Jack ‘sewn on his derrière’.1

When news arrived back in London of Nasser’s coup, emotions ran high. Prime Minister Anthony Eden insisted that, whatever happened, the Egyptian dictator could not be permitted ‘to have his hand on our windpipe’.2 The man whom Eden had earlier dubbed an Arab Mussolini must not be allowed to strangle Britain. The headlines in the London press told the same story. From the Daily Mirror, which proclaimed ‘Grabber Nasser’, to the more sober Daily Telegraph, the papers almost without exception conjured the historical lessons of Hitler’s and Mussolini’s rise to power to explain Nasser’s actions.3 A potent mixture of fear and anger drove the British response.

How was it that the fate of the Suez Canal had come to assume such terrifying proportions in the British imagination? To understand this, we have to return to the crisis year of 1942. As Axis forces under Rommel stormed their way across North Africa, British defeat in Egypt seemed imminent. In February, the British ambassador, Miles Lampson, forced a change in Egypt’s unsympathetic government at the point of a tank barrel, a humiliation which Egyptian army officers, Nasser included, would never forget. Then, in June, the British imperial garrison at Tobruk surrendered. Such was the British anxiety that summer that the embassy in Cairo started to burn its sensitive files. The loss of Egypt, and with it the Suez Canal, threatened a calamity which would cut the British Empire in half. It was only in November, with the decisive victory won by General Montgomery at El Alamein, that this existential threat receded. For the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, there was no doubt how much was at stake in this desperate battle for the Middle East. ‘Our history and geography demand that we should remain a world power with worldwide interests’, he insisted in a speech delivered at the end of October 1942 against the backdrop of the battle of El Alamein.4

The Second World War had demonstrated, then, that the Middle East, with Egypt at its heart, was vital to Britain’s survival as a great power. Egypt acted as the arsenal of Britain’s war effort, its air transport hub and a crucial way-station to the east. In order to rebuild the shattered British economy after the war, the new Labour government, which came to power in 1945, focused on the development of the resources of the Middle East, especially its oil. This would be the engine of British economic regeneration and imperial salvation. The emergence of the Cold War only enhanced the region’s strategic importance as a potential defensive barrier to Soviet expansion.

But what were its boundaries? Ever since the term had been coined at the beginning of the twentieth century by the American naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan, the ‘Middle East’ had been a geographically elastic concept. Its use was always likely to provoke two questions: ‘middle of what?’ and ‘east of where?’ In fact, the boundaries of the Middle East fluctuated for British governments based on strategic and material needs. When Mahan had coined the term, the key British strategic interest was the protection of the sea approaches to India, which necessitated control of the Suez Canal and the Gulf. Later, during the Second World War, the ‘Middle East Air Command’ expanded to cover countries as diverse and distant from one another as Egypt, Kenya, Somalia, Libya and Greece. The emphasis on defence of the region against the Soviet threat after the Second World War led to the further inclusion of Turkey, and even Pakistan, once the partition of the Indian sub-continent had taken place in 1947.

Geographical precision and consistency regarding the boundaries of the ‘Middle East’ therefore remained elusive. But beyond the strategic rationale of the Cold War and the material interest provided by access to its oil, the region was also often further defined as encompassing states where Islam was the majority religion, even if this usage raised more geographical questions than it answered.5 Whatever its imprecision, for post-war British prime ministers, as we will see, the idea of the ‘Middle East’ remained an essential concept.

Semantics, at any rate, did not detain British leaders who were plotting the revival of their economy after the Second World War on the back of the exploitation of the Middle East’s oil reserves. High priest of the orthodoxy that the Middle East must be defended no matter what was the Labour government’s combative Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin. ‘In peace and in war’, he told his Cabinet colleagues in 1949, ‘the Middle East is an area of cardinal importance to the UK, second only to the UK itself.’6

Bevin’s thinking was shared by his Conservative shadow, Anthony Eden. In 1945, Eden had commented that the defence of the Middle East was ‘a matter of life and death to the British Empire since, as the present war and the war of 1914–18 have proved, it is there that the Empire can be cut in half’.7 The historian John Darwin has rightly observed that ‘Britain’s ability to use the Canal Zone and its bases… was its greatest surviving geostrategic asset outside the Home Islands.’8

The value of this asset consisted of more than just the Suez base’s utility for the strategic defence of the region against the Soviet Union or the role of the Canal in the transportation of Middle Eastern oil. The British Empire at its height could be likened to a three-legged stool, which rested on the support of the Royal Navy, the British Indian Army and the financial resources of the City of London. In the post-war world, the power of the Royal Navy had dwindled relative to the might of Soviet land forces and US naval forces. After 1947, the British Indian Army was no more. The power base provided by Britain’s Middle East Empire filled the strategic gap left by the relative decline or loss of these other assets. Moreover, as John Darwin has argued, ‘Among British leaders, no one was more sensitive than Anthony Eden to the grand geopolitics of Middle East power.’9 It was this largely unspoken assumption about the foundations of Britain’s world power that helped to explain the intensity with which Eden reacted to Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal Company. The emotions of anger and fear competed for primacy in his response to the crisis in much the same way as they had for earlier British leaders making key decisions for war and peace.10

Across the span of half a century, the same emotions which drove Eden’s response to the Suez crisis also had echoes in Prime Minister Tony Blair’s reaction to the al-Qaeda attacks on the United States on 11 September 2001. Fear drove Blair’s response. ‘The Middle East’, he later wrote, ‘is endlessly fascinating and frightening.’11 His belief that terrorism coupled with weapons of mass destruction presented an existential threat to the Western way of life led him to advocate the Anglo-American military campaigns in Afghanistan and later in Iraq. When his former Foreign Secretary, Robin Cook, together with senior officials in the Foreign Office, warned him of the parallels with Eden’s actions over Suez, Blair dismissed them out of hand. But the Iraq War over which he presided was to prove just as politically divisive as Eden’s intervention over Suez half a century earlier.

If fear was the principal emotion which drove Eden’s and Blair’s actions, there was one crucial difference between the political landscapes against which each of them operated. Eden acted against the wishes of the President of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower, whereas Blair acted hand in glove with President George W. Bush. Acting with or against the grain of the Anglo-American ‘special relationship’ made a huge difference to the outcome in each case. Whereas Eden’s military action over Suez was essentially thwarted by American opposition, Blair’s intervention in Iraq was pressed forward, for good or ill, on the back of US determination and support.

The Anglo-American ‘special relationship’, then, lay one way or another at the heart of Britain’s engagement in the Middle East from Suez onwards. From its very inception against the backdrop of the Second World War, there had always been competing conceptions as to the meaning of the term ‘special relationship’. For its architect, Winston Churchill, it was an evangelical concept, founded in common values, shared history and culture. But, on its first public outing, in his famous ‘iron curtain’ speech delivered at Fulton, Missouri in March 1946, Churchill also offered a distinctive moral formulation of the concept. The special relationship was also about combating the ‘growing challenge and peril to Christian civilization’.12

Half a century later, Churchill the evangelist found his most direct successor in Tony Blair, an apostle for the creed of the ‘special relationship’ if ever there was one. But there were also British leaders who took a more hard-headed approach to its realities, most notably Harold Macmillan, who had famously told the young Richard Crossman at Allied Forces Headquarters in North Africa during the war: ‘We, my dear Crossman, are Greeks in this American empire… We must run A.F.H.Q. [Allied Forces Headquarters] as the Greek slaves ran the operations of the Emperor Claudius.’13

This instrumental view of the special relationship, in which the cunning British would channel American power to their own ends, found a similar expression in a contemporary Foreign Office document which proclaimed regarding the Americans that ‘they have enormous power, but it is the power of the reservoir behind the dam, which may overflow uselessly, or be run through pipes to drive turbines. The transmutation of their power into useful forms, and its direction into advantageous channels, is our concern.’14

One way or another, then, relations with the United States lay at the heart of the engagement of successive British prime ministers in the Middle East from Anthony Eden through to Tony Blair. The Anglo-American relationship, in fact, defies easy categorization. On one level, the two countries were competitors, vying for economic advantage in the lucrative markets of the Gulf which opened up on the back of the oil boom from the 1970s onwards. On another level, they were the closest of allies, combining to thwart Soviet advances into the Middle East during the Cold War era, and to block the expansion of regional powers like Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in its aftermath. They also found common cause in the crusade against global Jihadism with its roots in the Middle East. But the tension between the evangelical formulation of the alliance as a force for global good and its functional formulation as an instrument of British foreign policy, and hence as a means towards an end rather than an end in itself, continued to plague British policy-making. The clearest indication of this comes in the stark conclusion to the report of the Chilcot inquiry, set up to investigate Britain’s commitment to the war in Iraq under Tony Blair: ‘Influence should not be set as an objective in itself. The exercise of influence is a means to an end.’15

So, Britain was neither to be driven out of the Middle East by a United States which sought to replace it as the leading power, nor to act as Washington’s unquestioning lieutenant in the prosecution of wars in the region. The Anglo-American relationship was one of both competition and cooperation, rivalry and alliance. While the first question posed by any British prime minister about a new crisis in the Middle East was often ‘what does the President think?’, this did not mean that London would always unquestioningly follow the line framed in Washington. Far from it: indignation at the dictates of US domestic politics and exasperation at the byzantine process of policy formation in Washington were consistent characteristics of the British approach to the Middle East throughout the period surveyed here.

The Suez crisis of 1956, then, with which this book begins, was not ‘the lion’s last roar’, but instead the first act of an enduring drama of British military intervention in the Middle East, which culminated in the ill-fated Anglo-American wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya in the early twenty-first century.

False Prophets approaches this troubled history through the eyes of its principal protagonists: the British prime ministers who ultimately decided policy towards the Middle East. On one level the justification for this approach is straightforward. The key events which dominate the narrative – Suez in 1956, Operation Granby in 1991, the response to 9/11 and the interventions in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya – were all characterized to an exceptional extent by prime ministerial action and initiative. The fact that we often speak of Eden’s Suez operation and Blair’s Iraq War underlines how much the prime ministers concerned, for good or ill, came to own these wars. As the historian Peter Hennessy has rightly observed, ‘war is an intensely prime ministerial activity’.16

What is particularly striking, though, is the depth of prime ministerial passion which came to be engaged over the Middle East. Eden’s warning that Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal Company was a fundamental threat to British survival, and Blair’s claim in the run-up to the Iraq War that the combination of terrorism and weapons of mass destruction represented an existential threat to the Western way of life, are familiar. But, in between Eden and Blair, successive prime ministers, one way or another, found their passions directly engaged in the region. For some, such as Wilson, Callaghan and Thatcher, it was an attachment to Zionism and Israel which drew them in. But for others such as Macmillan, Douglas-Home and Heath, the belief that Britain’s future safety and well-being depended directly on developments in the Middle East was deeply ingrained.

Ultimately, then, the fears, foibles and follies of successive occupants of 10 Downing Street all came to be played out on the stage of the Middle East.

PART I

THE NASSER THREAT

1

ANTHONY EDEN: SUEZCIDE OF A STATESMAN1

TRY AS HE might in later life, Sir Anthony Eden could never come to terms with the fact that the Suez crisis had ruined his reputation. It was not so much the use of force in November 1956 to try to retake the Suez Canal and topple Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, for Eden was hardly the first or the last British prime minister to resort to military intervention to achieve his goals in the Middle East. It was the tissue of lies intended to conceal Britain’s collusion with Israel and France in planning the invasion of Egypt which dogged Eden throughout the remaining twenty years of his life. His strict adherence to this cover story – that Britain and France were impartial international peacekeepers intervening to prevent fighting between Israel and Egypt from blocking the Canal – was a fascinating study in private self-deception as much as public face-saving.

Even after his fall over Suez, Eden still could not bring himself to admit the truth of what had happened. He had time to reflect on events during a voyage to New Zealand in early 1957 and his extended diary entry at this time drips with bitterness against the Americans, the United Nations, opposition politicians and others who had thwarted his plans: ‘Collusion is a new term of abuse for concerting foreign policy between free allies. Only Nasser and Moscow may plan with secrecy and impunity.’2

Eden’s diary reflections on Suez also provide some clues as to why a politician who had previously found himself on the right side of history, resigning as foreign secretary in February 1938 over the Chamberlain government’s appeasement of Mussolini, now found himself so disastrously on its wrong side. A grand conspiracy was developing in the Middle East, Eden believed, sponsored by the Soviet Union and enacted by Nasser, which would sweep away all the Arab regimes friendly to Britain. Not only was the United States not prepared to act to thwart this conspiracy, but, through its principal diplomat, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, it was ‘twisting and wriggling and lying to do nothing’. Worse still, there were those in Washington who actually wanted to exploit the crisis to undermine the British position: ‘It has to be admitted that there is an American school of thought that cordially wishes us out of the Middle East.’3 All of this meant that action was essential.4

Eden was not alone in this selective recollection of history. Two decades later his closest diplomatic accomplice in collusion, Foreign Secretary Selwyn Lloyd, penned his own memoir, Suez 1956, which similarly glossed over the uncomfortable facts. Called on to vet the manuscript before publication, Sir Michael Weir, who had occupied a junior position in the Foreign Office during the crisis, but had now risen to the rank of assistant under-secretary with overall responsibility for the Middle East, wrote that ‘I must confess I found all this painful reading… The impression I am left with is of an extended exercise in rationalisation by an old man who has learned nothing and forgotten quite a lot.’ Among a range of dubious assertions, Weir noted that ‘perhaps the most extraordinary claim is that one of the main aims of the operation was “to create the conditions for an Arab-Israel settlement”’.5

Weir’s observation points towards a further paradox of Eden’s role over Suez. He was an unlikely candidate to break his reputation for the clandestine pursuit of collusion with Israel and France against Egypt. On the contrary, one of Eden’s main achievements as foreign secretary in Churchill’s peacetime government was the conclusion in 1954 of an agreement with Egypt for the staged evacuation of the British Suez Canal Zone military base, the continued occupation of which had been a running sore in Anglo-Egyptian relations since the Second World War. A brief honeymoon in bilateral relations ensued during which it seemed possible that a new relationship might begin. Against this backdrop a secret plan, codenamed ‘Alpha’, was indeed launched to promote Arab–Israeli peace. Developed by the British Foreign Office official Evelyn Shuckburgh, in cooperation with Francis Russell of the US State Department, Alpha aimed at brokering a bilateral settlement between Egypt and Israel. Shuckburgh, who had been personally close to Eden during his service as his Private Secretary between 1951 and 1954, had a ringside seat to observe his neuroses, and recorded them in a candid diary which has been heavily mined in accounts of the Suez crisis.6

Top of the list was the frustration engendered by his long apprenticeship under Churchill. The ‘will he, won’t he?’ saga of Churchill’s resignation ran throughout the term of his peacetime administration from 1951 to 1955. Meanwhile, Eden, the heir apparent, fumed in impotent rage. As foreign secretary he was of course reprising a role he had played successfully before. Indeed, a string of achievements in 1954, including the brokering of deals to end the war in Indochina and to secure West German admission to NATO, alongside the Anglo-Egyptian agreement, suggested a man at the height of his diplomatic powers. But solving the Arab–Israeli conflict was a different matter. In his diary, Eden claimed the credit for launching the Alpha peace initiative in the first place. In October 1954, over dinner at the British embassy in Paris, he wrote, ‘I persuaded Dulles with difficulty to embark upon [the] joint exercise for [the] Middle East… We began in Cairo.’7

In February 1955, Eden journeyed to the Egyptian capital to meet the revolutionary leader whom he would later liken to Mussolini, Gamal Abdel Nasser. Nasser, who had seized power in Egypt in 1952 through a coup executed with a group of like-minded ‘Free Officers’, was a man who, through force of personality and rhetoric, could dominate a rally of tens of thousands of people. He had huge energy and vigour. Yet, in private, with his high-pitched laugh and quick movements, he could sometimes seem a more nervous and uncertain figure. His tendency to fix his gaze in the distance made establishing personal contact difficult. Eden himself was more typically courteous and proper, rather than warm or engaging, at first meetings, particularly in a formal setting.

The encounter was not helped by the political circumstances in which it took place. Top of the list of points of conflict was a recently concluded defence agreement between Turkey and Iraq, which seemed to Nasser to throw down a challenge from Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri Said for leadership of the Arab world. Nevertheless, Eden’s immediate account of their meeting was largely positive. ‘The atmosphere was most friendly especially on all that concerned Anglo-Egyptian relations’, he wrote to Churchill. ‘I was impressed by Nasser who seemed forthright and friendly…’ There was a crucial catch, though: Nasser was ‘not open to conviction on this Turco-Iraqi business’. Indeed, at one point in their discussion Eden asked Nasser directly not to treat the pact as a crime, to which Nasser replied, laughing, ‘No, but it is one’. Eden rationalized Nasser’s opposition in personal terms: ‘No doubt jealousy plays a part in this, and a frustrated desire to lead the Arab world.’8

Sometimes smaller details also provide useful clues as to the tenor of a meeting. The discussion and the ensuing dinner were held at the British embassy, which no doubt accounted for some of the background tension from the Egyptian side, encapsulated in Nasser’s sardonic remark that he was interested to visit the place from which Egypt had been governed. He was also evidently piqued that he had not been warned that the dinner would be a black-tie affair, having turned up in his military uniform. Meanwhile, Eden’s genuine efforts to defuse the tension were apparent from his greeting of Nasser in Arabic and his attempts to flatter him.9 Eden’s wife, Clarissa, who attended the dinner at the embassy, found that Nasser conveyed a ‘great impression of health and strength – terrifically broad and booming’. Of the business conducted, she noted that ‘A[nthony] came up very late, having had a good talk with Nasser except regarding the Turco-Iraq Pact, upon which he was very bitter.’10

With all the focus on the Turco-Iraqi Pact, the exchange did little to advance Plan Alpha. Eden probably thought it wise not to open up a topic as controversial as making peace with Israel when Nasser was already agitated by events in Baghdad. As it was, circumstances soon conspired to make the peace initiative even more precarious. On the night of 28 February 1955, Israeli forces carried out a major reprisal raid into the Gaza Strip, which had been administered by Egypt since the conclusion of the 1948–9 Arab–Israeli war, inflicting significant casualties on the Egyptian army. The raid, which highlighted the weakness of Egypt’s armed forces, changed Nasser’s outlook on the conflict with Israel. Coupled with the signature of the Turco-Iraqi Pact it focused his attention on the struggle for leadership in the Middle East.

When Eden subsequently orchestrated Britain’s accession to the Turco-Iraqi Pact, which was now renamed the ‘Baghdad Pact’, in April, the battle lines for Suez were drawn. Given Nasser’s words during their meeting in Cairo, Eden should not have been surprised that he saw the British action as throwing down a challenge to Egyptian leadership in the Middle East. But, as far as Eden was concerned, ‘it would be most unwise to try to help Nasser at the cost of weakening our support for the Turco-Iraqi Pact. Our declared object is to make the Pact the foundation for an effective defence system for the Middle East.’11 Eden remained preoccupied with the longer-term aim of ensuring security in the region through the promotion of a defence agreement linking key states to Britain, and did not realize the extent of the danger posed by alienating Nasser.

Given that joining the pact proved to be such a crucial misjudgement on Eden’s part, it is worth standing back and asking what it was he was trying to achieve and why he failed. The answers to these questions take us to the heart of Eden’s understanding of the vital importance of the Middle East in British foreign policy. In 1955, Britain was still the most important great power in the Middle East. The region mattered to Britain for two reasons. Firstly, it was the strategic hinge of empire. The fact that Churchill had elected to deploy a significant portion of Britain’s limited armoured reserve to defend the region against the Axis threat during the dark days of 1940–41 showed its importance.

Eden shared this thinking. True, in 1952 he had authored a paper advocating the shedding of overseas commitments and the recognition of the strict limitations on British power, but the defence of the Middle East remained a strategic priority for him. Even the 1954 Suez base agreement, criticized by the Empire diehards within the Conservative Party as an example of scuttle under pressure, was for Eden merely a tactical withdrawal aimed at securing Egyptian cooperation in the strategic priority of defending the Middle East against the potential Soviet menace.

Coupled with this strategic rationale for the continuing British presence in the Middle East was an economic imperative of overriding importance: the securing of oil supplies. Whereas in 1938 only 19 per cent of Western Europe’s oil had come from the Middle East, by 1955 90 per cent of supplies came from the region.12 For Britain, oil produced in the Middle East was of even greater importance because it could be purchased in Sterling, unlike oil drawn from Western hemisphere sources in the United States or Venezuela which would have to be paid for in Dollars. So, unhindered access to Middle East oil supplies was a vital British national interest. Given that the bulk of these supplies were transported via Suez, the Canal came to be likened to Britain’s jugular vein. The potent image of strangulation at the hands of a dictator was one to which Eden resorted again and again during the Suez crisis.13

If Britain’s interests in the Middle East were vital, the threats to them were real so far as Eden was concerned. On the one hand, he perceived the region as vulnerable to subversion by the Soviet Union. References to the grasp of the Russian ‘Bear’ littered his correspondence during the Suez crisis. On the other, he feared the subversion of friendly Arab regimes by hostile nationalists. The Baghdad Pact was supposed to counter the first threat, linking states in the region together for their collective defence against the USSR. But it was also seized on by Eden as the means of renewing Britain’s treaty relationships with friendly Arab regimes, most notably Iraq, but later Jordan too. It was this dimension of the pact which made it the target of hostile Arab nationalists.

Nasser was not the only Arab leader to be antagonized by the Baghdad Pact. Eden reserved special venom for the role now played by King Saud of Saudi Arabia. ‘An absolute monarch of a medieval State was playing the Soviet game’, he wrote. In fact, it was not only the Baghdad Pact, perceived by the Saudis as a British attempt to promote their dynastic enemy, the Hashemites of Iraq, which had antagonized King Saud. The forcible reoccupation by the British in October 1955 of the otherwise obscure Buraimi oasis on the Saudi–Abu Dhabi–Omani frontier opened up a running sore in Anglo-Saudi relations. Beyond the promise of oil lying underneath the oasis, it was the blow to Saudi prestige caused by British action over Buraimi which sparked what developed into a Saudi-financed proxy struggle with Britain over the coming years.

Buraimi and the Baghdad Pact also provide the key to the final element of the Suez puzzle: Eden’s parting of the ways with the United States. While Eisenhower’s Secretary of State John Foster Dulles had originally been enthusiastic about the Baghdad Pact, his enthusiasm cooled as Eden took it over and ran it as an instrument of British policy. Worse still from the American perspective was the British action over Buraimi. Eden saw King Saud’s approach as having been egged on by representatives of the US oil company Aramco, who were anxious to prospect for oil in the area.14

The discussion about Buraimi during Eden’s visit to Washington early in 1956 provides an indication of American concerns. ‘The United States had a big stake in the area’, Secretary Dulles argued. ‘There were large oil reserves and the Dhahran air base.’ It would cause the United States great difficulties if Britain did not attempt to placate the Saudis. But Eden was having none of it: ‘The British position in the Persian Gulf was of the greatest importance for the United Kingdom. We depended on it for our life. If we retreated once more over the Buraimi affair our position in the Gulf would be untenable.’15

Eden later came to see this visit to Washington as a turning point. Try as he might, he could not get agreement either on a public joint warning that Britain and the United States would act together against aggression in the Middle East, or on joint contingency planning. ‘The pretext was that Congress would not agree. In vain I pleaded [the] seriousness of the situation… But I made no real progress. And then there was always Buraimi and Saudi ambitions backed up by [the] US to divide us.’16 For Eden the visit finally lifted the veil both on the balance of power in the post-war Anglo-American relationship and on the hidden motivations behind US policy.

Eden’s sense of urgency in securing Anglo-American agreement was dictated by the deterioration of the situation in the region. In response to the Gaza raid and the conclusion of the Baghdad Pact, Nasser had embarked on a propaganda campaign against Britain and its allies conducted with great effect via the ‘Voice of the Arabs’ radio station. Eden’s own assumption of office as prime minister after Churchill’s retirement in April 1955 had not diminished his personal interest in foreign policy. On the contrary, he followed events in the Middle East with the keenest attention. On one telegram he scribbled, ‘Anything in our power to hurt Egyptians without hurting ourselves?’17

He also showed considerable exasperation with the approach adopted by his successor as foreign secretary, Harold Macmillan. The Eden–Macmillan relationship lay at the heart of the British government’s response to events in the Middle East during 1955–6, and it was not a happy one. On one level the two men had a lot in common. Both graduates of Eton and Oxford, they had each fought in the First World War and exhibited significant gallantry under fire. In the inter-war years, both found themselves on the anti-appeasement wing of the Conservative Party. But it was Eden who had secured the more significant political advancement, serving as foreign secretary under Churchill during the Second World War. The two men emerged as political rivals during Churchill’s peacetime administration between 1951 and 1955, and even Eden’s attainment of the top office after Churchill’s retirement did not mute this rivalry. Above all, Eden seems to have seen Macmillan as a political opportunist, a self-seeking individual who cloaked his intense personal ambition in a veneer of detachment.

Eden’s feelings about Macmillan can be discerned from his diary entry for 1 October 1955, in which he complained that ‘I am as much irritated by H[arold]’s patronising tone as by his absence of policy. He follows Dulles’ argument like an admiring poodle and that is bad for Foster and worse for British interests in [the] Middle East.’18 The feeling was mutual. In the face of Eden’s continuing attempts to interfere over Alpha, and his demands that telegrams to Dulles should be cleared with him first, Macmillan threw his papers on the desk, exclaiming, ‘I might as well give up and let him run the shop.’19

Still, there was more at work here than simply a personality clash between two leading Conservative politicians. Eden’s sense that British and American interests in the region were diverging was epitomized by the development and eventual demise of the Alpha peace project during 1955–6. During the summer of 1955, Eden believed Dulles had started to back out of the plan by arguing that he must make it public in an emasculated form for domestic political reasons well ahead of the presidential election due in the autumn of 1956. The public statement eventually made by Dulles on 26 August, while agreed in principle with Foreign Secretary Macmillan, caused Eden significant consternation in private. In his diary he wrote:

In my judgment he [Dulles] has been steadily reducing their chances of achieving success in the Middle East. A little courage for another six months might have done the trick. Unfortunately Macmillan had not understood how much our original intentions were being warped. He showed little fight and was generally too susceptible to a compliment or two in a telegram from Dulles, who is no doubt glad to be rid of me.20

Eden’s private thoughts as expressed in his diary underline that his personality clash with Dulles was another important element in the decline in Anglo-American relations during the months leading up to Suez. Put simply, there was no trust between the two men. Eden saw Dulles as a sanctimonious fraud, a man who dressed up domestic political manoeuvres in moralizing Cold War rhetoric. As Eden saw it, the ‘trouble with Dulles was that he regarded British and French interests in the Middle East as colonial and American interests in South-East Asia, or anywhere else in the world, as virginal’.21

Still, the threat posed by Nasser’s conclusion of an arms deal with the Soviet Union at the end of September 1955 temporarily brought London and Washington back together. In a bid to forestall any possible further Soviet advance in Egypt through the offer of assistance in the building of the Aswan High Dam, Nasser’s key domestic economic project, it was agreed to promote a Western offer of aid via the World Bank. At the same time, efforts to move Alpha forward were resumed, with Eden making an important speech referring to the matter at the Guildhall in London on 9 November. In response, Nasser privately indicated his willingness to conduct peace talks, albeit only through intermediaries.22

But normal service, in terms of Eden’s growing anger with Nasser, was soon to be resumed as a result of events which took place in Jordan between December 1955 and March 1956. Jordan mattered to Eden because it presented the next most promising candidate to advance his scheme for building a new foundation for Middle East defence through the Baghdad Pact. In December 1955, General Sir Gerald Templer, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, was despatched to Amman with the aim of persuading King Hussein and his government to back Jordan’s accession to the pact.

The choice of Templer to carry out such a delicate mission was misguided. Arrogant, abrasive and impatient, he was ill-suited to carrying out discussions in Amman, where diplomacy was normally conducted over refreshments at a leisurely pace. Add to this mix the tensions surrounding the pact, and the poor relations Templer established with the Jordanian Prime Minister, Said Mufti, whom he termed ‘a jelly who is frightened of his shadow’, and the recipe for failure was complete.23 At the end of a frustrating week in Amman, faced with the adamant refusal of Prime Minister Mufti to initial a letter of intent to join the pact, Templer was forced to admit defeat. ‘I am afraid I have shot my bolt’, he cabled London. His explanation for his failure was typically direct: ‘the trouble is none of them has got any bottom’.24

The subsequent outbreak of serious rioting in Amman put paid to any remaining hopes that Jordan might yet join the pact. While there was genuine and widespread public opposition, it was on the Egyptian and Saudi role in fanning the flames of Jordanian hostility that Eden once again focused. In private correspondence with King Hussein, King Saud admitted his hostility to the pact, which he called an ‘outside plot’ to divide the Arabs.25 Eden, meanwhile, was adamant that the attempt to secure Jordan’s accession had been foiled by Egyptian propaganda backed by Saudi money.

Evelyn Shuckburgh, Assistant Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, noted in his diary that Eden now ‘compared Nasser with Mussolini and said his object was to be a Caesar from the Gulf to the Atlantic, and to kick us out of it all’.26 But even Shuckburgh, who still advocated a more pragmatic approach to Nasser, was not without his recurring fears: ‘in the lucid watches of the night I could not avoid the conclusion that all Asia is moving steadily out of our ambit and that our Western civilization will be seen strangled and subjected, with its bombs unusable in its pocket’.27

At the same time, Shuckburgh reflected that ‘I feel the whole M[iddle] E[ast] situation turns on whether Glubb can keep order in Jordan.’28 He was right. In many ways General Sir John Bagot Glubb, the British commander of the Jordanian Arab Legion, personified the British presence in the Middle East. A man who had dedicated his life to building Jordan’s armed forces, Glubb’s personal prestige in the country was huge. But this was part of the problem. The young King Hussein had come to feel that he would not be master in his own house while Glubb commanded Jordan’s armed forces. Even before the Baghdad Pact riots it had been clear there were tensions in their relationship.29

Egged on by a group of nationalist officers within the army, the King now moved to dismiss Glubb on 1 March 1956. With echoes of Shakespearean tragedy, Shuckburgh recorded that ‘the King has done it, and Glubb leaves in the morning for Cyprus. It is a monstrous piece of ingratitude…’ For Eden meanwhile, it was ‘a serious blow, and he will be jeered at in the House, which is his main concern. He wants to strike some blow, somewhere to counterbalance.’ Eden believed that Nasser was the secret architect of Glubb’s dismissal despite the evidence that it was Hussein’s own initiative. ‘He is now violently anti-Nasser’, Shuckburgh wrote.30

The two things which by now had come to preoccupy Eden most, then, were his domestic political vulnerability over events in the Middle East and the relentless evaporation of British prestige. In domestic political terms, Eden’s position was surprisingly weak. Despite having led the Conservative Party to a convincing victory in the May 1955 general election, a sense of drift set in soon afterwards with the press attacking his lack of authority. No doubt Churchill’s leadership would have been a tough act for anyone to follow, but Eden showed himself to be excessively sensitive to criticism. His reshuffle of the Cabinet in December, which saw Macmillan moved from the Foreign Office to replace Rab Butler as chancellor of the Exchequer and Selwyn Lloyd promoted to foreign secretary, was an attempt to address this criticism. But the immediate effect in terms of the press reaction was negative.

On 3 January 1956, the Daily Telegraph published a leading article titled ‘Waiting for the Smack of Firm Government’. In a critique which was as devastating of Eden’s mannerisms as it was of his leadership, it noted, ‘There is a favourite gesture of the Prime Minister which is sometimes recalled to illustrate the sense of disappointment. To emphasise a point he will clench one fist to smack the open palm of the other – but this smack is seldom heard. Most Conservatives… are waiting to feel the smack of firm Government.’31

Not only did the reshuffle fail to staunch press criticism, it created discontent within the Cabinet. Macmillan had not wanted to leave the Foreign Office and viewed his move as a judgement by Eden on his conduct of foreign policy. Butler was similarly discontented at leaving the Exchequer. Meanwhile, Lloyd was widely seen as a cipher sent to the Foreign Office so Eden could act as his own Foreign Secretary.32

The domestic political fallout from the Glubb dismissal was serious for Eden. Shuckburgh observed ‘universal jeering’ in the newspapers and called the debate in the House of Commons ‘a calamity’. Eden seemed ‘completely disintegrated – petulant, irrelevant, provocative at the same time as being weak. Poor England, we are in total disarray.’33 Even Eden’s wife Clarissa, the most sympathetic of observers, wrote in her diary that ‘the events in Jordan have shattered A[nthony]. He is fighting very bad fatigue which is sapping his powers of thought. Tonight’s winding up debate was a shambles.’34

In private, Eden’s position regarding Nasser had now hardened still further. ‘He was quite emphatic that Nasser must be got rid of. “It is either him or us, don’t forget that”’, he told Shuckburgh.35 Minister of State for Foreign Affairs Anthony Nutting went even further and claimed that ‘from now on Eden completely lost his touch… Driven by impulses of pride and prestige and nagged by mounting sickness, he began to behave like an enraged elephant charging senselessly at invisible and imaginary enemies in the international jungle.’36

Both men in fact present an exaggerated picture of Eden’s disintegration at this stage. He was still open to persuasion to pursue pragmatic policies and was not yet fully engaged in a monomaniacal pursuit of Nasser. Over Jordan, for instance, his initial anger was superseded by a more practical acceptance that King Hussein’s protestations of continuing good will were genuine, and that Britain should work covertly to retain its position by bolstering pro-British elements in the army.37

Nor was the shift in Eden’s approach to Nasser an isolated, personal response. Not only did the British government’s policy towards Egypt change, but that of the Eisenhower administration also changed as the attempt to entice Nasser to cooperate with Plan Alpha foundered. A memorandum, codenamed ‘Omega’, prepared by Dulles and approved by the President, included a range of diplomatic, political and economic tools which might be used to put Nasser under pressure to abandon his burgeoning relationship with the Soviet Union. These policies were to be coordinated with the UK as far as possible. But the stress placed in the document on building up the US relationship with Saudi Arabia and on the regional leadership role of King Saud promised further Anglo-American tensions given the unresolved differences over the Buraimi oasis.38

Dulles’s private exasperation with Eden’s approach was reflected in an unpublished interview he gave in which he described the British as ‘just desperately grasping at straws to find something that will restore their prestige and influence in the world’. He bemoaned a ‘series of very grave errors’ which Britain had made in the Middle East, including hijacking the Baghdad Pact, occupying Buraimi and attempting to get Jordan to join the pact. ‘When the British get into any kind of a mess they say “well, you must be true allies and back us up in everything we have done, and if you don’t it’s terrible”.’39

As Dulles’s comments made clear, the central Anglo-American difference over the Baghdad Pact remained. On 5 March, Eden sent an impassioned plea to Eisenhower arguing that ‘we can no longer wait on Nasser… if the US now joined the Baghdad Pact this would impress him more than all our attempts to cajole him have yet done.’ But the American refusal to join the pact remained adamant. This was despite Eden’s claim that ‘there is no doubt the Russians are resolved to liquidate the Baghdad Pact. In this undertaking Nasser is supporting them and I suspect that his relations with the Soviets are much closer than he admits to us.’40

Eden’s claim was no idle boast. Since November 1955, information from a source purported to be close to Nasser’s inner circle, codenamed ‘Lucky Break’, had been reaching MI6. The thrust of this intelligence suggested that Nasser was much closer to Moscow than had previously been thought, but its bona fides remained uncertain. Evelyn Shuckburgh confided to his diary that ‘the evidence that Nasser is playing closely with the Russians is very disquieting – unless it has been planted on us, which I think is very possible.’41 But, largely as a result of the turn of events in Jordan, by the beginning of March 1956 Eden gave considerable weight to the ‘Lucky Break’ information. He now tried to persuade the Americans, who had been receiving the same information, to lend it similar credence.42

On 19 March 1956, Sir Ivone Kirkpatrick, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, and Eden’s closest official adviser during the Suez crisis, wrote to Ambassador Roger Makins in Washington urging that it was important to ‘bring the disturbing facts to the attention of the Americans’. The reason for this was simple: ‘Moves against him [Nasser], and ultimately his elimination, depend for success on American support being wholehearted.’43 Having spent much of his earlier career dealing with Nazi Germany, Kirkpatrick was a hawk who regarded Nasser as a dictator out of the Hitler mould. Eden shared the same fears both about Nasser’s intentions and about the inconstancy of American support in bringing him down. There remained an important difference between the American approach, which aimed at weakening Nasser, and Eden’s approach, which from now on sought to overthrow him.

Besides the credence he gave to ‘Lucky Break’, Eden also apparently lent an open ear to those in MI6, led by its deputy director, George Young, who argued that covert operations should be conducted to undermine Nasser’s influence in Syria and Saudi Arabia, as a stepping stone towards overthrowing Nasser himself and installing a more pliant Egyptian regime.44 Covert action proceeded along two main tracks. The first track, which was coordinated with America’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), aimed to block Nasser’s influence in Syria by engineering a pro-Western coup in Damascus. This was codenamed ‘Operation Straggle’. The second track, which was never fully agreed with Washington, aimed at Nasser’s removal and the installation of a new regime in Cairo. As early as December 1955, Macmillan had alerted Eden to the existence of a new ‘revolutionary group’ in Cairo which might be utilized against Nasser. Eden for his part had approved discussion of ‘what alternative possibilities to Nasser there may be’.45

These discussions took place among a select official group and they intersected over the coming months with the entrepreneurial activities of a small band of Conservative backbenchers with intelligence ties led by Julian Amery, Macmillan’s son-in-law. Amery was a leading figure in the so-called Suez Group, a motley collection of right-wingers who had opposed the 1954 deal to evacuate the Suez base and who continued to put Eden under pressure for his supposed appeasement of Nasser. A natural plotter, once described as having been ‘born with a silver grenade in his mouth’, Amery was a strong advocate of Nasser’s overthrow. His scheming helped increase the pressure on Eden from within the Conservative Party to act firmly against Nasser.46

Something of the sense of gathering crisis which gripped not just Eden but the whole of the government at this time can be gleaned from Shuckburgh’s diary entry for 13 April: ‘these days are deep in concern about the future of the Middle East. Endless meetings, on oil, on the Suez canal, on the Palestine question… and they all show up the same grim truth – that Western Europe is dependent on the oil, and that Nasser can stop it coming if he wants to, by closing the Canal or the pipelines.’47 When the Soviet leaders Nikolai Bulganin and Nikita Khrushchev paid a visit to London later that month, Eden himself delivered the same uncompromising message. Without oil supplies Britain would starve to death: he was ‘absolutely blunt about the oil because we would fight for it’.48

Ironically in view of what was to follow, it was now in Washington, not in London, that the initiative was finally taken to withdraw the offer of Western finance for the Aswan High Dam, which had been dangled before Nasser as an inducement to abandon his ties with the Soviet Union. The hostility of the US Congress to providing aid to Nasser led Secretary Dulles to inform the Egyptian ambassador, Ahmed Hussein, on 19 July that the offer was now void.49 That same hostility was shared in Britain and reflected in the Sunday Express headline ‘Not One Penny’, which ran the previous weekend, arguing that British taxpayers would be outraged if they had to pay for the dam.50

Nasser’s reaction, in nationalizing the Suez Canal Company, was dramatic. From the outset it was clear that two objectives jostled for space in the Eden government’s response. On the one hand, there was the imperative of securing the Canal and making sure that the oil would continue to flow. On the other, there was the desire to topple Nasser. The subsequent military planning became tied in knots trying to reconcile these objectives. Would a landing on the Canal suffice to topple Nasser or was a full-scale invasion of Egypt necessary? Macmillan, who emerged as the leading hawk in Cabinet, urged decisive military action. When Eisenhower expressed his strong reservations about the use of force in a telegram to Eden,51 and despatched Assistant Under-Secretary Robert Murphy to London to calm the British, Macmillan did his best to frighten him all he could.52

The Chancellor was also the first to champion concerting action against Nasser with Israel. He raised the matter on 2 August and again the following day, arguing that ‘the simplest course would be to make use of the immense threat to Egypt that resulted from the position of Israel on her flank’. It would also be desirable to make sure that Israel attacked Egypt and not Jordan since the latter move would activate the Anglo-Jordanian defence treaty. Macmillan was not yet able to persuade his colleagues and it was agreed to consider the question of Israeli participation in military operations again at a later date.53

Macmillan did not give up. In a move which enraged Eden he visited Churchill to argue his case. ‘Unless we brought in Israel, I didn’t think it c[oul]d be done’, he told Churchill, who set off to visit Eden at Chequers straight after the meeting. He told him that ‘we should free our hands about Israel’.54 Eden was not amused. When Macmillan tried the next day to present a paper outlining these hawkish views to the inner circle of the Cabinet, the so-called Egypt Committee which had been established to manage the crisis, Eden refused to allow the document to be circulated. As the Chancellor started to speak to his ‘little note’, Eden interrupted and told him it was ‘not just a little note’ and that he had no business trying to circulate papers without his permission.55 In his diary Macmillan fumed about this ‘very foolish and petty decision of this strangely sensitive man… I discovered later that the source of the trouble was the Churchill visit. Eden no doubt thought that I was conspiring with C. against him.’56 Having spent so long as Churchill’s heir apparent, Eden was very sensitive to any attempt to undermine his authority by using his predecessor.

Still, Macmillan’s paper was a radical document which struck to the core of the dilemma facing the British military planners. There was no point in simply reoccupying the Canal, he argued. Britain had abandoned that position earlier since it was untenable. Instead, a different plan altogether should be considered, ‘the purpose of which would be to seek out and destroy Nasser’s armies and overthrow his government’. The plan to occupy the Canal could be ‘preserved as a cover plan, but it would not be the main plan’. ‘The object of the exercise, if we have to embark upon it, is surely to bring about the fall of Nasser…’ Macmillan concluded by once again advocating involving the Israelis.57

The Chancellor continued to sketch out his thoughts on an extravagant canvas. Clarissa Eden noted in her diary that his conversation tended to be littered with sweeping historical analogies. On one occasion in Cabinet Lord Salisbury, Lord President of the Privy Council, had lost his patience and burst out, ‘I really don’t see any resemblance between us and Queen Elizabeth I!’58