0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Seemingly inspired by Fanny Hill, Fanny by Gaslight is the tragic life-story of a young girl born to two lovers and brought up in the seediest possible corner of Victorian London. Her early life as well as her adulthood is littered with pimps, prostitutes, drunkards and schemers but she herself stands apart from the degeneracy around her...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

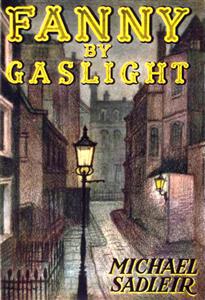

Fanny By Gaslight

by Michael Sadleir

First published in 1940

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Fanny By Gaslight

NOTE

Fanny by Gaslight is a novel, whose plot and characters are wholly imaginary. But because it is specifically dated and the events mainly take place in London, care has been taken to maintain period-accuracy and to give invention a basis of fact.

The institutions and scenes presented as characteristic of London night-life at the dates in question, are purely fictitious as regards locality and in detailed description. But little is made to occur which, in some form or somewhere, did not actually take place. Similarly one or two of the characters, in themselves imaginary, have life-stories borrowed and blended from those of real people. The manner of speech and the slang used are so far as possible in period; and although liberties have been taken with London topography (for example there was never a Panton Passage, a basin off the New River or a Larne Circle) Fanny’s London is innocent of anachronisms.

Differences in style between the various sections are deliberate. The first section and the last, which tell a tale of our own days, are written as the author wished to write them. Parts One and Three of Fanny’s story are told by her in the first person but written by Warbeck in the nineteen-thirties; they are therefore modern as to narrative, but ‘period’ as to conversation. Part Two of Fanny’s story, told in the first person by Harry Somerford, is more nearly period throughout, because it purports to read as a contemporary account of events which took place during the eighteen-seventies.

M.S.

INTRODUCING FANNY HOOPER

Now that he had started her remembering, recollections—like flotsam on a river in sudden spate—came dancing, gliding, bobbing and bumping across her reluctant mind. Some in themselves were pleasant, even lovely—her first visit to the Crystal Palace and the new tartan dress she wore; mamma’s prune-mould, with whipped cream piled in the centre, overflowing and dribbling down the smooth, purple-black flutings of the outside; the brooch from Mr Seymore; mamma’s story told in the firelight of the Becketts’ parlour, and the picture it conjured of a strip of golden sand, of rocks warm in the sunshine and of the deep blue-green of a hidden pool; “Vandra” or water-sprite; the discovery of Andrew; the happy carefree days at Aughton; dear staunch old Chunks; the pagan luxury of “Florizel Thirteen”; and finally the climax of them all—that brief enchanted life with Harry, and the joy of loving and serving him and seeing his eyes smile.

It seemed that after Harry went she had known no real happiness, nor hoped for it; but had been thankful for such intervals of surface contentment, security and excitement, as fortune brought her. Of contentment there had been little enough; of security, thanks to Kitty Cairns and dear kindly little Ferraby, what should have been sufficient; of excitement (as if excitement mattered!) plenty and to spare. . . . Some memories, if memories you wanted, were pleasant enough. Others however were horrible—things she had striven and striven to forget and at last forgotten—only now to recall them again, as vividly as though they had never been hunted from her mind.

Why had this man Warbeck asked her to remember? Why had she consented? “Don’t be a fool, Fanny” she told herself. “You must have money and he will get you money—just for remembering.”

But while half of her approved the commonsense as irrefutable, the other half fought desperately against the encroaching shadows of the past. She hated the past, whether it had been sweet or bitter; she was done with the sort of life she had known, almost done with life altogether. Here in Les Yvelines she had found peace for the few years left to her. And he had destroyed it. No—interrupted it only. She could change her mind, tell him that on second thoughts. . . . If she now refused to do what he asked, refused even to think of anything but the daily nothings of her quiet retreat, that peace would come again. “Without money?” queried the tart voice of commonsense; and to that question no heroic answer came.

She was lying in a wicker chair on a sort of covered platform in a corner of the garden at the Hotel de la Boule d’Or. It was early afternoon and very hot. The untidy grass was drenched in sunlight and the rambler-roses fell in a matted curtain between the dazzle without and the deep shade in which she sat. There was hardly a sound near at hand, save the burring of a solitary grasshopper in the sunlit garden and an occasional rustle in the pile of dead leaves which lay behind her against the penthouse-wall. From beyond the buildings came the noise of a lorry grinding down the street, then fading in the distance. The old woman lay very still. A cat, full length on a window-ledge a little to her right, lay very still also. The hotel seemed to be asleep; the little town seemed to be asleep.

Sleep came easily—and not only on hot summer afternoons—to the threadbare town of Les Yvelines-la-Carrière. Half-way between Versailles and the western fringe of what used to be called the Ile de France, it lay at the foot of an escarpment which marked the boundary of one of the more westerly of the chain of forests surrounding suburban Paris. Thus to the east of Les Yvelines and partly to the south, rose a steep, tree-crowned ridge, while flat fields and marshy meadows stretched west and north.

The place was very poor. Apart from a saw-mill, in forlorn competition with better equipped rivals for favours of the Eaux et Forêts, no industry survived; for the great quarry which gave the town half its name had been abandoned many years ago, and was now a sinister amphitheatre draped with weeds and ivy, scooped out of the hillside and already half-hidden by encroaching trees. The inhabitants, therefore, lived on agriculture; collected for sale fallen timber, cêpes, wild strawberries and lilies of the valley from adjacent areas of the forest; and thus contrived to live a frugal, apathetic life in a place which—though barely forty miles from Paris—was seemingly forgotten.

For not even the dubious benefits of tourism came plentifully to Les Yvelines, though it had things to show as good—or which would have been as good, with money to spend on repairs and advertising—as many far more famous places. Once it stood on a high road; but in those days motors were scarce and travellers made careful calculations about train journeys. Then, in the nineteen-twenties, a new big motor-road was driven across the plain to northward, which missed Les Yvelines (awkwardly hidden under the barrier of hills) by six miles, and took its tourists with it. Now only very determined lovers of antiquity or persons genuinely in search of solitude found their way to Les Yvelines—with results delightful to such as hate motoring sightseers, but sadly unfavourable to the town’s economy.

The Boule d’Or—except for a squalid tavern near the station (a very minor station on a branch-line and a mile from the town)—was the only hotel Les Yvelines possessed. It was an old-established house, whose age was now more evident than its establishedness. But although the widow Bonnet had neither cash nor incentive to “modernise”, she maintained with the stubborn pride of a true ménagère the standard of her simple cooking and the comfort of her beds, and saw to the casual but adequate sweeping of her tall, carpetless and sparsely-furnished rooms.

On this hot June afternoon the Boule d’Or showed no more sign of life to the street than to the garden. The flat four-storey facade, once grey-washed, now cracked and streaked with brown and deeper grey, rose sheer from the narrow pavement. On the ground floor the rusty paintless shutters were closed; before the main door hung a curtain of striped canvas, which, being only a year old, seemed unsuitably blatant in its vivid colouring. Two dusty trees in tubs, placed on the doorstep, threw into almost vulgar relief the green and orange brilliance of their back-drop. The name of the hotel, in spaced letters of tarnished gilt, clung unsteadily to the wall under the second storey windows.

The street in which the hotel stood was the main street of Les Yvelines, inasmuch as it prolonged from the south the one-time turnpike, debouched into the irregular space in front of the church, turned the left flank of that beautiful but crumbling building and, crossing a wide square bordered with low houses, divided by a stream and centred by a walled pond, passed out through an untidy suburb toward the station and the new arterial road.

It was called Rue Neuve, which—considering there was not a house in it of later date than the mid-eighteenth century and many far older—bore pathetic testimony to the longevity of the town, and emphasised, a little distressingly, its decayed old age.

Into the empty silence of this Rue Neuve broke, first the chuff-chuff of a small car and then the car itself—a little Peugeot, driven by a coatless young man in a beret. At his side sat a girl with a mop of yellow hair. The car came from the direction of the church and slowed uncertainly as the street narrowed. The young man spoke to his companion, gesturing with one hand toward the hotel. She did not trouble to follow his gesture, but merely smiled. Her eyes were heavy with contentment, and the smile said: Anything you like. I don’t care.

The car stopped at the Boule d’Or and the young man got out. He wore pale trousers with a belt, a white singlet and canvas shoes. Pushing the gaudy curtain aside, he stepped into the shadows of the hall. The girl sat motionless in the car, gazing in front of her, seeing nothing. In a few minutes the man returned accompanied by a plump maid in an overall, who seized the small suitcase from the dickey and opened the door for the girl to alight. They disappeared into the hotel. The young man got into the car again and drove it slowly into a tunnel-like gateway which at the far end of the hotel-facade gave access to the so-called garage.

Ten minutes later the old woman in her wicker chair behind the matted ramblers heard voices in the garden. The sound was welcome. Any intrusion of the present kept reverie at bay. Lying there alone with the hot silence all about her—faces, hands, rooms, sounds, even smells from the past crowded and jostled intolerably. Now she could keep them away—if only for a few moments—wondering who was coming, perhaps watching them when they came. Chance was kind. A young man and a girl with yellow hair came slowly into view. They were manifestly French. His arm was round her and she leant drowsily against him. Here and there in the neglected wilderness of garden stood chairs and tables. The newcomers chose places in a patch of shade, across the garden from where the old woman sat but well within her view. The plump maid brought a tray with glasses and siphon, poured menthe-Vittel, smiled encouragingly and stumped away. The visitors sipped their drinks, and then, as though flung together by invisible hands, were in one another’s arms. For a few moments they sat, pressed close one against the other. Then the girl turned slightly and, with her arms round his neck, slid backwards on to his knees. He bent to her mouth, and as the kiss clung her arms whitened with the effort of crushing her lover’s face against her own. When at last he raised his head, she let her arms fall limply, and lay a moment with closed eyes. Her ripe wet lips were parted, her breast rose and fell, and one could almost hear the beating of her heart. He sat looking down at her, a tiny smile of adoration creasing his lean dark cheeks. Then he bent again and, lips almost touching hers, whispered into her mouth. She faintly nodded, lay a second longer in happy relaxation before swinging herself quickly to her feet. With a vigorous movement she ran her fingers through the shining mass of her hair, shook it back and stood waiting. The young man rose and picked up the tray. Side by side they moved toward the terrace-door of the hotel and passed out of the old woman’s sight. As they passed, the sunshine lighted the contents of their two glasses to a livid golden green.

She stirred uneasily in her chair. Her ally, the present, had cruelly and uncannily betrayed her. Those two young things—so much in love, so fiercely happy in the refuge they had found—might have been phantoms from that portion of the past she dreaded most. She had not cried for years, yet now she felt the tears pricking her eyes. With a veined and wasted hand she touched the neat white hairs which lay smoothly under her widow’s bonnet. “Oh Harry, Harry . . .” she muttered, and her head fell forward on to the pleats which ridged the bosom of her dress.

An hour or two earlier on this same day—shortly after one o’clock, to be precise—Gerald Warbeck was eating his lunch on the bank of one of the several solitary and reed-grown étangs which occur here and there in the forest above Les Yvelines. He had started from the hotel about ten o’clock, carrying in his rucksack some bread, two slices of galantine, two tomatoes, a piece of Gruyère and a bottle of Vin Rosé. He wore grey flannel trousers and a short-sleeved sports jumper. A thin linen jacket was tucked into the strap of his rucksack, and on his head he wore what he pleased to call a Panama hat. It was darkish yellow and rigid in its shapelessness. All the same it might have been a Panama, once. It had belonged to Warbeck’s Uncle Oswald.

Gerald Warbeck was in his early forties. He had a high colour and reddish hair. Until he reached the shade of the trees he wore sun-spectacles, and these—perched fiercely on his prominent nose under the aggressive brim of Uncle Oswald’s hat—gave him an air of stubborn determination. Actually (as became evident when spectacles and Panama were laid aside) he was neither stubborn nor determined, but a mild, rather intelligent man who, because he was more interested in deviations than in conformity, minded his own business and wished others would mind theirs.

By trade Warbeck was a book-publisher, who did a little writing on the side. He was seldom shocked by the things which shocked the British public, but often found either painful or disgusting things in which that public took delight. Consequently his taste and theirs were apt not to coincide. Further, his instinct for novelty outran the normal; and he had not even yet learnt to make allowance for the reaction-time—seven to ten years—which was common form among his compatriots when faced with any new idea in the practice or appreciation of matters of the mind. As a result, he published books far ahead of any possible acceptability, failed to sell them, and was duly chagrined when, years later, his competitors published others of similar character and got away with them. Further again, he refused to admit that political conviction justified an author in distorting truth or lapsing from literary integrity—a prejudice which lost him many opportunities of profit, but in return won him no particular esteem.

Finally, because he was interested in too many kinds of things, he could not think day and night of one job and nothing else; and, being one-third author to two-thirds publisher, was not without sympathy for writers’ grievances. These shortcomings placed him at a disadvantage vis-à-vis single-minded sloggers, who knew that sticking to a last meant getting in first, and usually did so.

But despite these handicaps, Warbeck made as much of a living as he wanted, enjoyed as much of his work as he inclined to do, and secured each year a short spell of perfect contentment by going off on his own and leaving no address.

One such spell was now in progress; and today, when after walking steadily for two hours and a half he had reached the étang, he placed his sack and stick on a mossy bank, found a comfortable seat against a tree-trunk, lit a pre-lunch cigarette, and told himself that this indeed was happiness. The scene before him had beauty, but also a remote serenity which was magically anodyne.

The étang was an elongated mere, perhaps half a mile in length but nowhere more than a hundred yards in width. It was pinched to a sort of waist in the middle, where a forest-track crossed it on a low flint bridge. Bull-rushes, flags and other reeds grew thickly round the shores; and already yellow iris flowers were starring their greenery, over which dragon-flies of iridescent blue hovered and darted. Beyond the reeds the water was so overgrown with floating pond-weed that clear patches were few. There was no wind in the trees, no ripple on the surface of the mere. Warbeck sat motionless, revelling in the dapple of sunshine on the opposite trees, the sweet woodland smell, above all in the silence. He felt part of another world or, if this were indeed fairyland as it appeared to be, that he was dreaming. He wished the dream to continue; and was glad to find that it persisted, even after he ground out his cigarette and unpacked his lunch. Only gradually, as he ate, did actuality seep back into his consciousness. He welcomed it, for he found that he was now ready for it and prepared to consider its problems with interest. It was as though his brief excursion into another sphere had soothed and refreshed him.

Naturally the first subject to present itself was that of the remarkable old lady at the Boule d’Or, and the strange progress of his acquaintance with her.

He had arrived at the Boule d’Or a week ago. It was his first visit to Les Yvelines, a place he had several times tried to fit into a preconceived itinerary, but always been compelled to miss. It was characteristic of Les Yvelines not to march with other places on a tourist’s route. Everything about it was just a shade awkward; and in nine cases out of ten it had to be skipped—as Warbeck had skipped it. This year, however, he had determined to get there and, to prevent any possibility of deflection, would make it his first objective after Paris. Eventually he had driven out from the city in a taxi, which he had picked up near the Montparnasse Station after a brief and heart-breaking study of the available train service.

And already he had stayed a week.

Certainly the place had justified itself. The hotel was just the kind of hotel he most enjoyed—out at elbows and a little uncertain as to sanitation, but with the faded dignity of a house with traditions, an easy friendliness of direction, excellent food and drink, and the sort of fundamental peace which at times he feared had altogether vanished from the world.

The town was no less rewarding, with its knot of narrow streets; its jumble of ancient houses propped crazily one against another; the desolate stretch of trodden earth beyond the church, planted with two long rows of dusty planes beside the sluggish stream.

As for the church of St Etienne itself, it was an enchanting medley of styles, each almost perfectly represented, all harmoniously slipping into tragic but lovely ruin. The west front was Late Decorated at its most exquisite; but where the elaborate tracery had perished or been deliberately smashed was makeshift cement, and some catastrophe to the rose-window above the main doors had been remedied by planks, nailed across the opening and brushed with creosote. The south transept had a renaissance interior, faultless in proportion and detail and reasonably preserved; the north should have had the same, but the work had never been completed, and the delicate carving of medallions and pilasters faded off into rough stone-work of a later date, which did not aspire to ornament and only just achieved utility. The nave and chancel were simple Gothic of the fifteenth century. Poverty had prevented paint; and the pillars, walls and roof were naked stone or plaster and greying wood—in places stained green with damp, generally discoloured and probably unsafe, but spared at least the niggling patterns and hideous colour-scheme of provincial catholicism. To crown all, across the Gothic and the renaissance, the eighteenth century (presumably during some spurt of local prosperity) had scrawled its grandiose signature. It had filled the west end with a huge organ-loft, whose front and curving stairs were tempests of baroque carving; at the corner of the north transept it had erected a monstrous pulpit, which swung upward in a spiral from a luscious base to a canopy in the form of a gilded shell. The once polished wood was dull and cracked; the gold a dim survival of itself. But still the spiral flung its curves to heaven, and the flamboyant piety which had created it stood side by side with earlier pieties, facing a common ruin.

Oddly enough the best preserved and most coherent feature of this dilapidated hybrid of a church were the windows. Of mid-sixteenth century date, they pierced the clerestory in series along both sides of the nave, and with boldness of design and graceful naivete depicted scenes from the Old and New Testaments. Attracted by their liquid colouring, Warbeck had studied them in detail, and discovered among them a rendering of the Garden of Eden. The composition demonstrated in words of one syllable the desire of man for woman, and was of a kind unusual in a sacred (or indeed in any public) edifice. This flash of candour delighted him; and was duly registered in that corner of his memory reserved for anything eccentric, pathetic, sinister or abnormal, which might come his way.

Seeing that to these attractions of Les Yvelines itself could be added the miles of forest-walks which lay within easy reach, this year’s holiday would in any event have ranked high among Warbeck’s experiments. When lavish chance produced the ultimate bizarrerie of the old lady at the hotel, it shot ahead of all its rivals. Never, he told himself, will you have such luck again. Go very carefully and make the most of it.

The afternoon of his arrival—was it indeed only a week ago?—he had encountered the widow Bonnet in the hall, as he was wandering out into the town. His previous meeting with her having been a purely professional affair of room and terms and formal courtesies, he took the opportunity to seek a better acquaintance. She was a small, demure grey-haired woman, very quiet in manner and simply dressed in a black frock sprigged with white. Her face was pleasant but worn with anxiety and a little melancholy. She received Warbeck’s polite greeting with a bend of the head and a faint smile, and would have passed on into her office if he had not made some friendly remark about the interest and antiquity of Les Yvelines. Yes, she agreed, it was an old place and lovers of old places found it attractive. “But they are few enough” she added with a return of her sad smile, “and we are off the track of modern life.”

Warbeck felt slightly embarrassed. Was this a gentle lament which called for condolence, or an implication that people of his sort were of no great use to a hotel and would gladly be exchanged for motorists or commercial travellers?

“I am sorry” he said lamely. “I suppose it is difficult, when one has to cater for uncertain guests.”

“Oh monsieur, I am not complaining. I have lived so long in Les Yvelines and grown so settled in my ways that I should not be happy anywhere else. But I was afraid you might find it too quiet and my hotel—well, not up-to-date in its appointments.”

“I assure you, madame” Warbeck spoke with the emphasis of conviction—“that I am the least up-to-date of living men and the Boule d’Or—so far as I have seen it and with an excellent déjeuner fresh in my mind—is precisely the sort of hotel I usually seek in vain.”

The rather stilted diction and the genuine warmth of this red-haired, large-nosed Englishman appealed to Madame Bonnet.

“Thank you, monsieur” she said. “I shall try to fulfil your expectations. The garden is pretty” she went on wistfully “though I wish you could have seen it a few years ago. My husband was alive then and kept it in better order than is possible today. So few young men stay in Les Yvelines; and the old ones, who might come and do the garden, get older and fewer every year. But even overgrown, it is pleasant to sit in. I like to take my coffee there in the summer, if there are not many people staying—and there seldom are.”

“You have people now? . . .”

“A couple last night, but they left early. And of course Madame Oupère.”

“Madame. . . ?” queried Warbeck. “And why of course?”

She smiled almost gaily.

“Pardon, monsieur. I am stupid. How should you know? Madame Oupère is an old English lady—very old—who has lived here now for several years. I do not know why she came or why she has stayed. Some sorrow probably, and in any event not my business. But without knowing anything about her or indeed becoming at all intimate with her (for she keeps her counsel) I have grown quite fond of her. I think we all have.”

Warbeck felt a twinge of curiosity. His instinct for a queer story stirred in its sleep and opened one eye. Also he was glad that this nice widow had a permanent pensionnaire.

“That is interesting” he said. “I do not think I saw her at déjeuner.”

“No, she does not as a rule come down until the afternoon. She is old, as I said. My niece Léontine looks after her as well as she can—takes her meals upstairs and helps her. But you will see her at dinner. . . .”

After a few more generalities, Warbeck took leave of his hostess. As he strolled down the street he found himself looking forward to a sight of the old lady from England who had lived alone in Les Yvelines for several years. He wondered what her surname really was.

They two were alone in the salle à manger—Warbeck at a small table near the buffet, Madame Oupère across the room at another small table by the window. She was a quaint enough little figure to satisfy any amateur of oddity. On her head was a close-fitting cap of white muslin, tied with a black-velvet ribbon which finished in a large bow half-way between crown and forehead. Her snow-white hair, parted in the centre, swept tidily to left and right and back over her ears. She wore a gown of black satin, very plain, with a touch of white lace at throat and wrists. Her tiny hands were innocent of rings, save for a plain gold band on her left hand; round her neck she wore a single string of pearls.

From this severe—almost puritan—setting an impish little face threw out its challenge. It was a lined face, of course; and below the high cheek bones wrinkles tugged at the corners of the mouth. But it remained the face of one who had not lost her capacity for merriment and cheerful cynicism, who still—through a pair of bright black eyes—could see the funny side.

Throughout the meal Warbeck covertly studied this remarkable little person—a process of some delicacy because, so far from ignoring his presence or shrouding herself in the aloof dignity dear to the British who encounter their kind in foreign lands, she was unabashedly studying him. The more he looked at her, the more he liked her looks. A Londoner himself, he could respond to what were surely a Cockney gaiety and a Cockney impudence in the tilt of the nose, in the long humorous mouth and in the flicker of mischief in the eyes. He was wondering how the inevitable acquaintanceship would begin, when she pushed back her chair, threw her napkin on to the table and prepared to leave the room. He bent over his dessert, feeling that to watch her even surreptitiously would be intrusive. He heard her steps tapping towards him on the plain polished floor—steps surprisingly brisk and firm—and was more apprehensive than surprised when they stopped by his table instead of passing onward to the door.

“Young man” she said abruptly, in a voice perhaps more unexpected than anything else about her—a deep contralto voice disturbing but delicious in its shadowy luxury—“You are an Englishman.”

Warbeck rose clumsily to his feet and stood in the awkward position of one who, unable to push table and chair apart, must droop inward at the knees, pretending to be upright.

“Yes” he replied. “Yes, I am.”

“I am English too” she said. “If an old woman asked you as a kindness to take coffee with her . . .”

“I should accept with pleasure. . . .”

She gave him a quick, almost a coquettish smile and moved away.

“In the garden” she said, as she left the room.

He sat with her in the garden while the twilight faded. Night fell, and the evening primroses hovered like huge white moths. The scent from a group of nicotines lay heavy on the air. The darkness was faintly lit by indirect reflection from the hotel. Here and there in the high wall a lighted window shone; from the glass verandah which gave on to the garden came a muffled gleam, and through the glass the plump little maid and another youngish woman, presumably Léontine, could be seen clearing the dining-room. Warbeck could see little of his companion who was sunk almost out of sight in a low wicker chair. He was grateful for the darkness which thwarted vision but left the listener free, for Madame Oupère was a siren to the ear. She talked a good deal in that low thrilling voice, asking questions, praising Madame Bonnet and her niece, retailing anecdotes of small events in Les Yvelines and of the idiosyncrasies of passing guests. But of herself she said almost nothing. Her name, he discovered, was Hooper. As he had guessed, she was London-born and London-bred.

Clearly it was impossible for Warbeck to question her; and he realised, when at last he rose to take his leave, that he had told her a great deal about himself and learnt very little in return. She bade him goodnight in a friendly way and thanked him for his company, concluding:

“Would you please tell Léontine, as you pass the bureau, that I would like to go upstairs?”

Warbeck had found a problem after his own heart, and for a while he lay awake devising explanations of old Mrs Hooper. When he awoke next morning he devised some more. They were all incorrect.

The acquaintance ripened rapidly; but although Warbeck now felt quite at his ease with his new friend, he was little better informed as to her personal history. Piecing together such indications as she let slip, he surmised that she had known not only many places, but many kinds of life; that she was no reader, having a fund of worldly knowledge gained at first hand, but little of what—in his faintly pedantic way—he called “cultural background.” She tended to flippancy, especially with regard to the established conventions and castes of her own and other countries, while her occasional comments on restriction-mongers—national and international—were hostile even to savagery. Warbeck began to suspect that the mutual sympathy which each had clearly felt at their first meeting, was in fact based on a fierce individualism common to them both—a suspicion which an incident of their fourth day of friendship tended to confirm.

About six o’clock in the evening, as he came downstairs, bathed and changed after a day in the forest, he met Mrs Hooper in the covered verandah. He had an English weekly paper under his arm and was bound for the café on the Place St Etienne, where he liked to sit for an hour before dinner. “Good evening, Mr Warbeck. You are going out?”

“Only down to the café by the church.”

“May I come with you?”

“Of course.”

The request surprised him, for he had never seen her leave the hotel and had assumed—without the least reason—that she was semi-invalid. But as they walked down the street, he noticed that she stepped securely for an old woman, and also that several of the people they met saluted her. Clearly she was a figure familiar in Les Yvelines.

Settled in the café—a homely place with a very small apparent clientele—she accepted a cigarette and asked for absinthe. Tasting it, she pursed her lips and twinkled across the table at Warbeck.

“Not the stuff it was” she said. “They’ve taken the life out of it—as out of most other things.”

“You have been a frequenter of cafés?”

“Cafés . . . divans, as we once called them . . . all manner of places. Not sitting outside, you know. In my day that would have been indiscreet. But inside . . . upstairs . . . in rooms. . . .”

Casually Warbeck picked up the English paper.

“I was reading here, just before I came downstairs, about raids on clubs and cafés in London—catching them out selling drinks after hours, you know. It angers me, this monstrous system of dressing up cops in evening clothes to catch poor devils out.”

Mrs Hooper nodded vigorously.

“We are all in leading strings nowadays. Our spirit is broken and even spies are honourable, when working for righteousness. They ought to be lynched. And they would have been in the old days. I’d like to have seen . . .”

She broke off and sipped her drink.

“Never mind . . . I’ve seen plenty . . . stupid to want to see anything more . . . .”

He took a chance.

“Tell me some of what you have seen. . . .”

She picked up her glass, and, as she put her lips to it, looked quizzically at him over the tilted brim. Replacing the glass on the table, she turned her head and stared across at the crumbling church-front.

“Shall I?” she mumbled, half to herself.

He said nothing. He had dared. It was for her to punish or reward.

“How do I know. . . ?” she began, and broke off abruptly; then shrugged her shoulders and fixed him again with her bright derisive eyes.

“I like you, Mr Warbeck. I like your big nose and your funny tufty hair. Also you are kind. You are big and sometimes clumsy, but I think you are gentle as well as masculine. Women—even old women—like that mixture, as I daresay you have found out for yourself. But I do not know you inside, do I? You may have dislikes, prejudices, principles, which I would wish to respect. . . .”

Again she broke off, and began playing with the white muslin cuff which sat demurely at the wrist of her simple black dress. Warbeck smiled at her.

“Thank you for liking me and for not wanting to ruffle my feathers. But I am sure you need not be afraid. I have my feathers. But they ruffle principally at hypocrites and brutes, and you do not seem to me either of those.”

She considered his words carefully.

“Brutal? No, I don’t think I have ever been that. As for hypocrisy, I have worn a mask most of my life, but I had to—at least I thought I had to. And yet I am still nervous of offending you. Let me ask you this—what in a year’s time will you remember most clearly of that church there?”

“The Adam and Eve window” he replied.

She flashed him a look, mock-scandalised. “Oh, Mr Warbeck!” she said, and her little face creased dangerously.

After a few moments she chuckled.

“I will tell you my story—or as much of it as you care to hear. It is not much of a story in itself; but I have known all sorts of people and seen all sorts of things, and so much of what I used to know has disappeared. Also you may be able to help me—for I am in a difficult position. . . .”

“Anything I can do. . . . Does the story start after dinner?”

“As you wish” she replied. “Shall we go back now? I am hungry.”

That evening and the following day, and the day after that, the story of Mrs Hooper, or rather her souvenirs, gradually accumulated. She was capricious as a teller of tales, sometimes talking readily enough, at others saying she was tired, or could not think of anything worth recalling, or insisting on retracing her steps and correcting some earlier inaccuracy. One evening when Warbeck put a casual question, hoping to launch her on a stream of reminiscence, she said:—

“I’m not in the mood tonight, Mr Warbeck. There’s something on my mind which I want to tell you.”

“Please” he replied. “Go right ahead.”

She gave a little laugh.

“I’m almost shy about it. I don’t like bothering you with my private affairs, but I have no one else to consult. So here goes. Well, to put it bluntly, I am broke. (Don’t be afraid. I’m not going to touch you for a loan.) When I came here about five years ago, I reckoned that I had enough money to live on for ten years and that I was not likely to need all of that. But two misfortunes occurred. The first was the failure of an American investment in the crash of 1929. The second has only just happened.

“There are some dwellings in one of the poorest parts of East London, of which I own a share. I have regularly received rents from them—not very much, but useful to have. These dwellings have now been condemned. The agents who transmit the rents have sent me the Council Surveyor’s report, and a very terrible thing it is. It makes me almost ill to think that for years I have been taking money from people living in such conditions.

“You see, I never went to the place. The share which is now mine was left me years ago by a dear friend who was one of the earliest philanthropists in the building of what were called Model Dwellings in the slums. He built this block, which at the time was thought a wonderful place; and so long as he was alive and interested in the dwellings, a decent orderly lot of people lived there. Forgive this long story; but I must make my dilemma clear.

“Well, my old friend died, and the ownership of the block passed into a number of separate possessions—of which mine was one. We new landlords were strangers to one another, scattered all over and mostly ignorant of or indifferent to our responsibilities. Control came to be exercised mainly by a firm of agents and rent-collectors, and by one or two of the part-owners, who took pains to keep in touch. I am afraid these people thought of nothing but how to make more money from the property.

“The dwellings are in a district which has been closely built up for many many years and has hardly any open spaces. Being fairly close to the centre of things, house-room is in constant demand, because working-folk can live there within easy, and therefore economical, distance from their jobs. The district has in consequence always been badly overcrowded. Evidently the men who were now managing our block of dwellings saw in this overcrowding the chance of collecting more rents. At any rate they allowed division and sub-division of flats, and took as tenants any who could pay.

“I do not try to excuse myself. I noticed my rents increased somewhat; but I was too busy with my own affairs to wonder why or to trouble to enquire. Even now I have learnt most of what I am telling you from the Report, and, by putting two and two together, have guessed the remainder. One thing is quite clear from the description—that the place deserves to be pulled down.

“The agents, when they advised me of the Council’s decision, urged me to join with other part-owners in demanding higher compensation than was offered. This I cannot and will not do. After reading what that place is like, I would like to refuse to take any compensation at all. But if I do refuse, I shall starve; for I have practically nothing else left.

“What am I to do, Mr Warbeck? That is what I want you to tell me.”

“Are the other owners standing out?”

“I have no idea. I suspect that the wish to do so originates with the men who have let the property get into this abominable state; they hope by writing round to get the rest of us carelessly to agree.”

“You know of no one who could go into it for you—a firm of solicitors—?”

She made a grimace.

“I have no solicitors; my bank is in Paris; I have no friends and I am too old to go to London myself.”

“I could make enquiries for you, when I get back” said Warbeck, doubtfully. “Go and see the agents or something—But I’m not much good at that sort of thing. What amount of compensation is actually offered?”

“My share would be about two hundred and fifty pounds. As a capital sum equivalent to what has been bringing in eighty or ninety pounds worth of rent per annum it is, of course, just comic; but then we had no right to extort anything like that amount from such a pig-sty.”

“And you would prefer not even to take the two-fifty?”

“Immeasurably—if I could survive without it. I should take it, and then give it back to the Council; for if I refused it in advance some of my charming co-owners would swallow it themselves. But it’s no use thinking of that, I fear. I must have the money; and it frightens me to think how I shall get on, if the payment is long delayed.”

“Let me sleep on it, Mrs Hooper, and see how things look tomorrow.”

Next day he said:—

“I have had an idea, which would enable you to do without your compensation money altogether.”

“Oh, Mr Warbeck, how wonderful! How happy that would make me!”

“Wait; you may hate my idea. It is this. There is a story in what you have been telling me. It wants filling out and arranging; but it might interest many people. Would you allow me to make a book of your memoirs and pay you for them?”

Her face clouded.

“Oh, I don’t think I should like that—making money out of people I have known—and out of my own feelings and sorrows. It is different just telling you. Besides you could not pay me enough to solve my difficulty; it wouldn’t be worth it.”

“Please, Mrs Hooper. I have thought this over carefully and am quite serious. I will prepare the book, subject to your approval, and publish it; and because I believe something good could be produced, I will pay you three hundred pounds for it in advance—now, if you wish. Then you will have your compensation—and a bit over—and can make your restitution when the matter of the dwellings is settled. As for your not remembering, I am sure that, if you try, lots more will come to mind. You shall talk; I will make notes, and afterwards I will write it out. I have a good memory for anything which interests me. Please think it over.”

She sat motionless, evidently turning the suggestion over in her mind. He had noticed before that she was a person who listened to what you said and gave it her attention. Not every one did that, and he welcomed the trait as part of her fundamental honesty.

“Yes” she said at last. “I will think it over. It is good of you to suggest it, and I would love to give that money back. Tomorrow evening I will have decided.”

“Then that is agreed. I shall be out walking all day tomorrow, and look forward to seeing you at dinnertime”.

‘Tomorrow’ was now today; he was out walking, and supposedly looked forward to seeing her at dinnertime.

Did he in fact? Most certainly. As he thought back over the course of his friendship with this strange solitary woman, he felt no regrets at the offer he had made to her. He had spoken on impulse, and three hundred pounds were three hundred pounds. She might, of course, refuse; but this he doubted. Of course, even if she consented, the story might be starved of material or he might handle it dully or clumsily. Conversely, it might be far too rich in incident and philosophy of an unmarketable—even an unpublishable—kind. Well, those were normal risks enough, and if the book did come off . . .

He looked at his watch. After three o’clock! The sunlight had changed its slant, and now shone full and hot on the heather and birch-saplings to his right. Soon it would find him also. Taking out his map, he planned his homeward walk; then knocked out his pipe, crammed the débris of his lunch into a hole in the ground, and clambered up the slope to the path. As his steps died away on the trodden sand and leaves of the woodland track, the raucous chatter and bark of a frog split the silence. Further down the mere other frogs replied, their raised throats swelling and throbbing among the pond-weed. The din mounted, crashed echoing against the banks of trees, and died away as suddenly as it had begun. Over the irises the dragon-flies, like tiny lengths of neon-blue, still hung poised a moment; then whisked away on soundless wings.

FANNY BY GASLIGHTPART ONE

Told by Fanny Hooper

PANTON STREET

PANTON STREET

I.

I was born in the late ’fifties—in ’fifty-seven or ’fifty-eight, no matter which—on the second floor of a house on the south side of Panton Street, and therefore within a stone’s throw of the Haymarket on one side and of Leicester Square on the other. This house was my parents’ place of business as well as their home. The ground floor was a licensed premise and therefore public; the first, second and third floors and the attics were private and residential. The building was tall and narrow, but of considerable depth, running back to a passage which in those days connected Oxendon and Whitcomb Streets. In consequence the upper floors, which for years were “home” to me, were awkwardly elongated and far from uniformly lit. The stairs were curiously broad for a house of no particular pretension but rather steep and very dark. This was because, after their first flight, they climbed up the middle of the house, so as to thrust the rooms to north and south, the only two directions from which daylight could be obtained. Over the well of the staircase was an octagonal skylight, through which—except for a few dazzling weeks each year, after Chunks had performed the hazardous job of cleaning the sooty panes—filtered a strangled gleam. The best rooms, looking on to Panton Street, only got sun in the late afternoon; those behind, although facing south, got none at all except on the attic floor, because only a few feet from their windows rose the virtually blank wall of the house across the passage. That blank wall of grimed yellow brick was so inescapable a part of my infant universe that it never occurred to me either to resent it or to wonder what it was. Later, when I made the acquaintance of its other side, it was too late for resentment and the focus of my curiosity had shifted.

The most important section of the building, because it represented my parents’ livelihood, was of course the tavern which ran from front to back at street-level. Beneath it was a still larger area, put to purposes of its own. Gold letters on a green ground, displayed on a board which ran the whole length of the Panton Street facade and blossomed in the middle into an ornate escutcheon, declared that here was THE HAPPY WARRIOR, and that the proprietor William Hopwood was licensed to sell Wines Spirits and Beers. Below the signboard was a wide expanse of frosted window, with at its extreme left two doors. Of these the larger and more magnificent gave access to the tavern, while the other opened on to a narrow passage which ran to the foot of the stairs leading to our private quarters.

I now realise (using, I suppose, some uncorrelated childish memory) that the huge ground glass window of THE HAPPY WARRIOR differed from its kind in two respects. First it was absolutely blank. No white appliqué lettering spoke of “Cigars”, “Billiards”, “Pyramid” or “Pool”; no wire blinds carried a painted promise of the diversions to be found inside. Second, it showed no light, even after dark. The tavern might be brilliantly lit, but the window from outside was black as brick-work. The main door was as laconic as the window, not even carrying a brass plate to ensure that passers-by knew it for an entrance to a public bar. Only one notice was affixed to any part of the building, and that had been tampered with. At the back of the block, on Panton Passage, was a door from which stairs led down to the basement. Over this door was a projecting board, which had originally read

HOPWOOD

SHADES

Some wag had painted out the first letter of the second word and added it, with an apostrophe, to the first. The new version had never been challenged and

HOPWOOD’S

HADES

remained, begrimed and out of centre, but tacitly approved and, by the time I began to take notice of the life about me, a phrase of general usage.

William Hopwood was as far from the typical publican of caricature as can be imagined. He was of medium height, very thin and with a long sallow lugubrious face, which a drooping black moustache made more doleful than ever. Actually he was not a melancholy man at all, but cultivated a mournful taciturnity as other men have cultivated a monocle or a languid drawl or a heavy geniality—in order to set off his peculiar form of humour. This expressed itself in an elaborately sarcastic manner of speech, and probably reflected a secret pride in his educated accent and lavish vocabulary. He had been personal servant to Mr Clive Seymore—now an important figure in the Government Service—and had not only travelled extensively with his master, but, having been treated more as a confidant than an employé, had made good use of his opportunities for self-improvement.

It might seem strange that while still a youngish man—he could not have been much more than forty when I was born—he should have exchanged agreeable and aristocratic service for tavern-keeping in the heart of London’s turbulent night-life. I believe that to those bold enough to question him he would explain that he wanted to get married and have a place of his own.

My mother was several years his junior—a cheerful round-faced, bustling young woman who looked exactly the farmer’s daughter that she was. I came to know that her parents were prosperous folk, who occupied a large farm on the fertile East Riding plains not far from Selby. They were the tenants of Mr Clive Seymore’s father—Sir Everard Seymore of Aughton Hall—so that no doubt William Hopwood met his future bride while attending Mr Seymore on a visit to his home.

I was an only child, and was thrown into my mother’s company more closely than is usual even with only children. Living ‘over the shop’ as we did, Mrs Hopwood’s domestic job was on the spot, and the shop being what it was and she being liable at certain times to have to take her share of supervision, the making of outside acquaintances and their entertainment at home were almost impossible. So she made a companion of her little daughter, who learnt from her to laugh at vexations, to have no great opinion of herself, and therefore not to sit in judgment on others but leave the world to go its way.

My mother’s closest friend—almost her only one—was a Mrs Beckett, who was the wife of an antiquarian bookseller in Chandos Street, and had a little girl not much older than I. Mr Beckett was in a good way of business, acting as ‘buyer’ for several gentlemen of wealth and position and at the same time carrying a considerable stock of good quality books, bought for his own account. Because his duties took him frequently from London to country houses and to country sales, and because he was a considerate and rather uxorious man, he engaged a qualified assistant to look after the shop in his absence, and did not—as so many of his kind were used to do—leave the responsibility to his wife. She, therefore, was more of a lady of leisure than most tradesmen’s wives and, being very fond of my mother, used that leisure to pay us frequent visits. A slow-moving, Junoesque woman, with a large oval face, a clear olive skin and eyes like sleepy velvet, she contrasted so strikingly with my vivacious little mother that even as a small child I relished seeing them together. Lucy Beckett and I would play with our dolls in a corner of the living room, while Lucy’s mother sat at the table sipping a glass of stout, and my mother ran to and fro between parlour and kitchen, chattering and laughing, as she kept an eye on her cooking in the intervals of ironing or mending or making clothes. Occasionally—but very occasionally—we would visit the Becketts in return, and if, as sometimes happened, Mr Beckett was at home, he always joined us for tea and greatly impressed my youthful mind by his assiduity in handing food to his wife and to my mother, carrying cups for replenishment, arranging footstools and cushions, and generally putting himself out to make the ladies comfortable. Nothing of this sort ever happened at home. William Hopwood took his breakfast and sometimes his midday dinner with his family (from five o’clock onwards he was either out or downstairs, and presumably supped in the tavern for I neither saw nor heard him until next morning) but during a meal he never stirred from his seat, leaving it to his wife to bring him food, remove his used plates and fill or refill his cup or glass. After he had finished, he would slew round in his chair, pick his teeth and read the paper, while my mother cleared the table and washed up.

Possibly this trifling difference of behaviour between the rarely-seen Beckett and the familiar Hopwood was the first unrealised challenge to my normal childish assumption that all households resembled our own. In any event, as I grew older I began to notice a lack of fundamental intimacy between my parents. I did not of course put it like that to myself. Probably I merely noticed that my mother got little response to her lively conversation, and that while she would rattle on about her doings and mine (very ordinary doings they were), he seldom volunteered any information in return.

Not that he was unkind to either of us. Indeed in his aloof ironical way he treated us with indulgent generosity. But he seemed to shut off, even from his wife, what must have been the chief preoccupations of his mind. This also I was led to notice by comparing him with Mr Beckett. Whenever we were at the Becketts and the bookseller was present, he would continually turn to his wife with this or that detail of his business—telling her where he had been, whom he had seen, what he had bought or hoped to buy; asking her opinion how to treat a difficult client, consulting her about some suggestion of his assistant’s, discussing the merits and demerits of a new messenger boy. But in my presence my mother was never thus confided in. For all we heard of the proprietor’s business, Hoppy’s might have been a dwelling-house and nothing else, except that, when for some reason he wished my mother to take charge of the desk downstairs, he would state briefly her hours of duty, and perhaps leave a message or two to be given to acquaintances who might be expected to come in. For a short while I assumed that, because my knowledge of what went on in Hoppy’s was so limited, my mother’s was equally so. But then one night I heard them talking in their room (it was below mine and the floor was a single one); and the talk went on so long that at last it flashed across me that possibly the subject was avoided on my account, that I was not supposed to hear how Papa spent his time. This, as can be imagined, set me thinking hard. But try how I might, I could not understand why, if Lucy was allowed to listen to her father talking of his work, I was not.

The cumulative effect of these—to my childish mind—inexplicable reserves, was to invest “downstairs” with the lure of forbidden ground, and to create without much delay an inclination to trespass.

It was queer how quickly—once the idea of forbidden ground had set its glamour on Tavern and basement,—my whole attitude to those places changed. That they were strictly out of bounds for me I had always known and never thought to question; nor had it ever occurred to me to disobey my mother even to the extent of peeping inside. But now that curiosity was aroused from another direction—now that I suspected that, not only certain rooms in the house but also an element in my parents’ lives were being kept from me, I felt a desire and then a determination to investigate.

II

I was, I suppose, about seven years old when I was taken by my parents to the Crystal Palace. The expedition entailed much preparatory discussion, as well as generous provision by William Hopwood for clothes for my mother and myself. Outings of any kind were very rare, and this was so clearly a super-outing that by the time the day arrived I was in such a flutter of anticipation as to be almost sick in advance with excitement and worry about the weather. But the appointed day was bright and mild and, after an early breakfast, we set off in company with Mrs Beckett and Lucy for the Victoria Terminus of the Crystal Palace Railway. My mother carried a large string bag full of sandwiches, cake and needlework; Mrs Beckett carried a satchel of plaited straw with similar bulges; William Hopwood, Lucy and I carried nothing at all save, in his case, a malacca cane with a fine ivory knob, in ours tiny parasols in careful harmony with our frocks. At the age of seven a girl-child hardly notices the clothes of her contemporaries, and how poor Lucy was dressed I have completely forgotten. But my own tartan frock, broad sash, white cotton stockings and gloves, shiny black boots and tiny saucer hat are still as vivid as ever, while the crowning embellishment—the silk parasol of a tartan identical with my frock—actually survives to this day.

We travelled by omnibus to the terminus, caught the desired train, and reached the grounds of the fabulous Palace about eleven o’clock. Hardly had we passed the turnstile, when a man hailed William Hopwood—a tall, fresh-faced man in a check suit, who wore his billycock hat at a jaunty angle.

“Hey there, Duke!” he shouted. “Who’d ’a thought of seeing you here?”

Hopwood shook the stranger by the hand and, turning to my mother and to Mrs Beckett, said in the mock ceremonious manner he loved to adopt:—

“Permit me to present Mr Mark Cunningham, who—not being blest as I am with the delights of domesticity—does not know a family outing when he sees one. Mark, my boy—my wife and Mrs Beckett.”

Mr Cunningham bowed and showed his teeth.

“Your servant, Duchess. And yours, ma’am. And these young ladies are, I suppose, the reason for my friend Hopwood’s truancy.”

He pinched my cheek (a familiarity I have never ceased to resent), patted Lucy on the shoulder and strolled alongside of us up the broad pebbly path. Before long he dropped behind with Hopwood, and the two men soon left us, to go into a bar.

“Why did he call you Duchess, mamma?” I asked, as soon as they had disappeared.

“Some of your father’s friends call him Duke” she replied.

“Why? He isn’t a duke, is he?”

She laughed.

“Not quite, darling. But he has a gentlemanly way with him. I suppose that is why.”

The day wore on. We bought ginger-pop at a stall and ate our sandwiches in the sunshine. We wandered under the vast arcading of the Palace, staring at statues and costumes in glass cases and models of engines and triumphs of ornament in porcelain, gilt and ormulo. We went on the tiny railway and fed the ducks on the pond and stared at the crowds. During the afternoon Hopwood reappeared, gave Lucy and me a shilling each for sweets or what we would, settled his wife and her friend on a comfortable seat, and wandered off again. In one part of the Palace grounds was a children’s play-park, with swings and see-saws and sand-heaps, a maypole with ropes and rings, a “bumble-puppy” and even an asphalt space for roller-skating. Lucy and I found our way there and soon made friends with a family of two boys and a girl, who were playing about under the eye of a nurse-maid. One of the boys seized a chance to occupy the bumble-puppy and proceeded to instruct me in the unfamiliar game. It was great fun hitting the ball in its string-bag so that it wound tightly round the pole, but not such fun when—rashly looking away—I failed to remark the counter-hit and was struck smartly on the head by the swinging ball. It knocked my hat off and bruised my ear and the game ended in tears and some confusion. But when composure returned, there returned with it a memory of what had so fatally distracted my attention. I had seen our new friends’ nurse-maid walking away with a young man; and, sure enough, now that her charges were ready to return to her, she was nowhere to be seen.

So far from being dismayed, the two boys leapt at the opportunity for adventure. They told us that, living in Sydenham, they had often been to the Palace, and knew a backway into the organ-loft which dominated the smaller of the two concert-halls—that used at night. True, they had been caught the first time and forbidden ever to go there again: but Ada had vanished and we should have plenty of time to make the expedition and rejoin her at an agreed rendezvous by the time she was likely to reappear.

“Ada has been off before with a young man” the elder boy explained “when we were here alone with her. And they stayed away—oh, a long time. And she fixed a meeting-place. Usually mamma is coming to find us, and then Ada stays with us. But today mamma is out calling, so do come on!”

Rather apprehensive, but unwilling to seem lacking in enterprise (in particular unwilling to be less daring than the boys’ little sister) we scuttled across the grounds to the Palace, and followed our guides to a region of passages and closed doors which even to the mind of a child had the flavour of “out of bounds”. The boys tip-toed along, peeping round corners and behaving with the extravagant secrecy of a game of Indians. At last they stopped at a narrow doorway, from which a steep spiral staircase led upward into darkness. I was now frankly scared; but it was too late to retreat, nor could I ever have found my way back through the maze of corridors. So, clutching Lucy’s hand, I crept up the stairs and, a few seconds later, was leaning on a balustrade looking down on the projecting platform used by the orchestra with, beyond it, the gloom of the concert hall.

The afternoon light was dimming; and the silent place, with its rows of empty seats and distant corners full of crouching shadows, was eerie and menacing. I felt the beginnings of fear, and was only a little consoled to see that both Lucy and our new girl-acquaintance were in the same plight. Meanwhile the boys were clambering silently about the steps and bench of the organ itself, which towered horribly above us, the tall pipes rising to what seemed a vast height before they were lost in darkness. I stared at them fascinated. The vents, curving in a wavy arch from left to right, looked like mouths; and as I crouched against the balustrade I seemed to see them leer at me, as though the pipes were a regiment of elongated and malevolent hobgoblins, only waiting a signal to bend downwards from above and seize upon me with their hideous tentacles.