Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Bedford Square Publishers

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

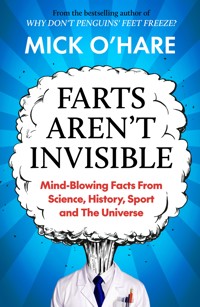

Is there an animal that can see farts? A mind-bending, brain-expanding cornucopia of facts for curious minds from the bestselling author of Why Don't Penguins' Feet Freeze? and Does Anything Eat Wasps? Reader Reviews ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 'Funny and given as a gift for a 10 year old. He loved it' ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 'Fantastic Book' ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 'Wonderful book to spark young minds' Own the room with this hilarious collection of fact-tastic myth-busters and jaw-dropping trivia exploring science, history, sport and lesser-known facts from across the universe. Did you know that the Moon has a Bishop? That ostriches DON'T bury their heads in the sand? And that powdered rice was used as cement in the Great Wall of China? What do souls weigh? What can't 60% of the human population smell? And what on earth is rhinotillexomania? And the big one...are farts actually invisible? The answers to these questions are all here. Challenge your brain, turn your world upside down and relish the irresistible mix of wit and wisdom. It's also a perfect gift for the brainiac in your life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 207

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FARTS AREN’T INVISIBLE

Mind-blowing Facts From Science, History, Sport and the Universe

Mick O’Hare

Dedicated to Pierre Levegh – a racer to the end – and all the victims of Le Mans 1955

With thanks, as ever, to Sally and Thomas.

Marathon

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter 1 FLATULENCE: Farts aren’t invisible.

Chapter 2 THE SOLAR SYSTEM AND THE UNIVERSE: You can still hear the remnants of the Big Bang.

Chapter 3 HISTORY: The British are coming.

Chapter 4 LIFE ON EARTH: Whale “vomit” is used in making perfumes.

Chapter 5 FOOD: Farmed salmon aren’t pink.

Chapter 6 MATHEMATICS: Why you should change your mind.

Chapter 7 LEAGUE OF NATIONS: No man is an island.

Chapter 8 SCIENCE AND SCIENTISTS: Humphry Davy makes candle makers redundant.

Chapter 9 OCEAN DEEP, MOUNTAIN HIGH: This is Planet Earth.

Chapter 10 DRINK: Shaken, not stirred.

Chapter 11 PLANES, TRAINS AND AUTOMOBILES: Don’t drive my car.

Chapter 12 THE ARTS, MUSIC AND FILMS: What happened to van Gogh’s ear?

Chapter 13 SPORT: Why are there two types of rugby?

Chapter 14 SPACE EXPLORATION: 400,171 kilometres from Earth.

Chapter 15 THE WEATHER: Why does tarmac smell when it rains?

Chapter 16 ROYALTY AND RELIGION: The Moon has a bishop.

Chapter 17 POLITICS: Albert Einstein could have been a head of state.

Chapter 18 HUMAN BODIES: Do our souls weigh anything?

Chapter 19 THE OLYMPIC GAMES: Spyridon Louis gets a new water cart.

Chapter 20 LIFE AS WE KNOW IT: The burning issue of the Gävle Goat.

Acknowledgements

Also by Mick O’Hare

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

Sometimes it is just being in the right place at the right time. In March, 1994, New Scientist kicked off its Last Word column asking readers for their everyday science questions. I happened to be in the eyeline of the boss, so he asked me to edit the new addition to the magazine.

There are huge scientific questions – how did the universe form, why is there only (as far as we know) life on Earth, and what the heck are we going to do about artificial intelligence? But this was not the remit of the Last Word column, which instead was devoted to everyday scientific trivia. We were frequently asked about farting, which gave inspiration to the book you are now holding. Although, I hasten to add, there’s a whole lot more in here too. My quest for knowledge and seemingly trivial facts has never dimmed. It can turn you into a pub bore, it can make you look half-decent at University Challenge, but it’s impossible to ignore that gnawing “I wonder why …?”. Perhaps you feel the same.

For me it’s simply a way of looking at the world, mentally voicing a question, diving down the rabbit hole, and popping back up with the answer, plus another 10 things you found while you were down there. From the internet, from friends, from observation, and from experimentation, the more obscure, the better. And then storing it all away. Some of it is never used. Most of it, I fear, is forgotten. But some of it creeps into my consciousness and stays, a huge accumulation of information with no egress. You should try living in my head … Does it hurt? concerned friends ask. No, not really, but I can’t rest until I have discovered the “who, what, why, where?” And it’s been accumulating seemingly for aeons.

This book is an outlet for all those perplexing, intriguing, obscure (and yes, frequently inconsequential) facts. I carry a notebook, but mostly I ponder. As a child I watched Atlantic waves roll up a Cornish beach and saw that every so often two would combine and the water would rush further up the sand with the accumulated volume driving it on. It meant that you could predict when people near the water’s edge would suddenly have to step back to avoid wet shoes. Everything you see or encounter is an opportunity to learn something.

Science is primarily about discovery, surely the driver of our species. Checking every available possibility and acting on the evidence. Facts are at the heart of science and I hope that you’ll be entertained, amused, and slightly edified. Some of my rather arbitrary passions are on the following pages – early space exploration, gastronomy, human biology, and, strangely, the Le Mans 24-hour race (do go, if you ever get the chance). Eagle-eyed readers will, I hope, forgive the indulgence of revisited obsessions, leitmotifs from an earlier era – we are looking at you, Mr Bond, with your vodka martinis, and you, Dr MacDougall, foolishly attempting to weigh the human soul – but when new evidence comes to light, I make no apology for keeping atop of subjects of vital importance to humanity.

So here it is – the whole gamut from moon landings to the Monty Hall paradox. There’s a saying in our family – often directed in mocking tones back at me – “I think you’ll find …” You may find yourself uttering it after reading this book.

Mick O’Hare

PS I have done my best to wheedle out urban myths (except for the most irresistible, flagged as apocryphal) but do get in touch if you know better.

CHAPTER 1

FLATULENCE

Farts aren’t invisible.

Well, perhaps not to everything. But they are generally invisible to humans. Thank goodness, you think, as you shiftily try to move to a different part of the room. But just because humans can’t see them, that doesn’t mean they are colourless. Humans can only see light that falls in the spectrum between the ultraviolet and infrared wavelengths. And because nearly every substance absorbs light, some gases absorb it at wavelengths we can’t see. But beware, some animals such as frogs, snakes, and goldfish can see infrared. Goldfish can even see ultraviolet too. So if you’re standing near your new date’s bijou aquarium, don’t be so certain you got away with it. The startled fish might report back later.

* * *

Farts can also be captured by thermal cameras, and anybody daring to eat too much broccoli or cabbage might produce enough sulphur in their gut to generate a visible cloud as it’s expelled.

The average adult farts approximately 10 times a day, creating enough gas to inflate a party balloon.

Henry II of England once gave one of his minstrels (Roland le Fartere – yes, really) a 12-acre estate for being able to perform his annual Christmas party trick of a hop and a whistle, followed by a fart. Roland’s descendants continued the tradition.

It’s reputed that zebras’ farts are the loudest (possibly apocryphal evidence suggests they can be heard five kilometres away).

Blue whales produce a fart bubble so big the aforementioned zebra could fit inside it.

In 2017 researchers at the University of Alabama released a definitive ledger of animals that can fart. Perhaps of greater interest is the ones that don’t appear on the list. Crabs, parrots, and octopuses don’t fart. Spiders and salamanders possibly do, while sea anemones don’t – but apparently their burps smell dreadful.

Most fish don’t fart, but instead package bubbles of waste gas (often ingested by surface feeding) into the gelatinous stools they deposit from their anuses.

Most farts contain odourless oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and methane. But the rotten-egg odour is caused by hydrogen sulphide – created by the microbes acting on the food that is passing through your gut.

Beans make you fart because they contain carbohydrates known as oligosaccharides. Our bodies lack the enzymes to break these down, so the bacteria in our intestines do it for us. The by-product of that is gas. Smelly gas. But don’t stop eating beans, as they are connected to a stronger immune system and better gastrointestinal health.

Foods that make you fart least include lean red meat, poultry, rice, quinoa, and oats.

Farts smell different in the bath because they are heated by the water as the gas passes through it, and the bubble also has less time to diffuse as it would in air, thus giving a concentrated hit to your nose as you sit above it. The fart gas may also exchange molecules with the heated water it passes through before reaching your nose, altering the odour.

Men fart more than women, but women’s are smellier, which rather goes against the grain of anecdotal evidence. Participants in an Australian trial had to record their farting in a diary. Men produced 12.7 farts a day, women 7.1. However, researchers in the US built on this earlier work by getting men and women to fart into a tube after eating pinto beans. Again, men farted more and produced more gas, but women’s farts had a greater concentration of hydrogen sulphide.

And yes, you really can ignite farts. The methane they contain is highly inflammable, which is why I wouldn’t recommend it. Rock musician Frank Zappa wrote about it in “Let’s Make the Water Turn Black” and it did not end well for Ronnie and Kenny.

Farts are so combustible that up until the 1980s they were infrequently implicated in fatal bowel explosions during routine operations on the gastrointestinal tracts of patients.

While it’s all subjective and hydrogen sulphide often appears atop lists of the world’s smelliest substances, thioacetone, an organosulphur compound, has been reported capable of inducing vomiting, unconsciousness, and nausea for up to an 800-metre radius if exposed to air. As a result, it is regarded as a dangerous chemical, simply due to its awful smell and the reactions it causes.

Joseph Pujol, known by his stage name of Le Pétomane, was a French professional flatulist. His act consisted of farting in tune to music and making the sounds of musical instruments. He also did cannon fire and thunderstorms. There is argument, however, as to whether Pujol really farted because, instead of actually passing intestinal gas, he was capable of sucking air inwards through his anus and expelling it to order.

Research has shown that if one person farts alone, they do not smile or laugh. Farts are only amusing when two or more people are present, with the glee increasing in proportion to the number of people in attendance. Once the group reaches a certain size and people are less familiar with those present, then overt amusement once more dissipates. Sniggering replaces laughter.

At the 1976 Olympics East German swimmers had 1.8 litres of air pumped into their colons through their anuses in order to improve buoyancy. “Cheating through farting,” wrote one West German newspaper. Later, in order to stop competitors having to clench their buttocks to hold the gas in, inflated condoms were attempted. Both failed to have the desired effect, because swimming speed relies on immersion in water rather than floating atop it.

The main gaseous constituents of (human) burps are odourless nitrogen and oxygen that are swallowed, collected in your oesophagus, and then expelled as you eat. If you’ve consumed a lot of fizzy drinks, carbon dioxide can be added to the mix. Burps are usually audible, unlike farts, which can be silent (see Myth Busting, below).

Astronauts have discovered that in zero gravity, stomach contents are not constrained by gravity. This means they routinely experience “sicky burps” or, in official NASA terminology, “wet burps”.

There is a poo standard. It’s called the Bristol Stool Scale and it has seven types running from “Separate hard lumps like nuts”, through “Like a sausage but with cracks on the surface”, to “Watery, no solid pieces, entirely liquid”.

Poo is brown because of stercobilin, a by-product of broken-down red blood cells, and bile, used to digest fat. The ideal stool colour, according to gastroenterologists, is a “deep chocolatey colour, like melted chocolate”. It should also sink to the bottom of the toilet.

The largest human turd ever recorded came from a Viking, who lived in York in England in the 9th century. It is 20 centimetres long and 5 centimetres wide, and was discovered semi-fossilised in an archaeological dig under a branch of Lloyds Bank. Detailed studies show that the owner ate a regular diet of bread and meat and suffered from worms. It is on display at York’s Jorvik Viking Centre.

Fossilised turds are called coprolites. The largest ever discovered belonged to a Tyrannosaurus Rex dinosaur. It is 67.5 centimetres long and 15.7 centimetres wide and was found near Buffalo in South Dakota. Nick-named Barnum, the fossilised poo is now owned by coprolite collector George Frandsen, who has about 1300 in his collection.

Our intestines are home to more than 2000 species of bacteria, a whopping 10 billion per cubic centimetre.

The biggest parasite that can live inside us is the 10-metre-long beef tapeworm.

Dogs poo in alignment with Earth’s magnetic field. In 2013 scientists from the Czech Republic and Germany measured 1893 random canine defecations (and 5582 urinations) and concluded that dogs align their spines with the north-south magnetic field before dumping. More research is required to discover why.

MYTH BUSTING

Myth: Farts can cure cancer.

In 2014 tabloid newspapers reported that smelling farts could cure some fatal illnesses, including cancer. Cue lots of giggling and people collecting their farts in sealed bags. Researchers at the University of Exeter and the University of Texas had discovered that hydrogen sulphide could prevent damage to the mitochondria of human cells and preserve the cells’ functions, meaning that there could be treatments for diseases involving cell damage, such as cancer or dementia. Because hydrogen sulphide is found in large quantities in farts, it was extrapolated that, when your partner farts, it might be wise to sniff it (or if you are single, sniff your own farts). However, the researchers had created a compound known as AP39, which delivers hydrogen sulphide specifically to the mitochondria. Outside sources, like sniffing gas from farts, would not have the same result. So that’s good news or bad news, depending on your opinion of your partner’s farts.

Myth: Silent farts are smellier than noisy ones.

It’s not true, according to Michael Levitt, a gastroenterologist in Minneapolis, who has spent almost a lifetime studying flatulence. “Volume has nothing to do with it. It’s down solely to what you have eaten and, secondarily, any infection you may be carrying,” he asserts.

Myth: Thomas Crapper invented the flushing toilet.

The story goes that British plumber Crapper invented the toilets we all use today and therefore his name became synonymous with the act of using one. But flushing toilets were invented in 1596 by the Englishman Sir John Harington, a courtier of Queen Elizabeth I. His version used 28 litres for a single flush and had no S bend. The design was improved on by Scot Alexander Cumming, who introduced flush valves and patented his design. Thomas Crapper doesn’t appear until the late 1880s, when he took out nine patents for different designs. It’s possible that the word “crap” doesn’t even derive from his name; it’s more likely to come from the Latin word crappa, meaning chaff (or a waste product). Crapper’s toilets did have his name on the side, however, which may have inspired or encouraged the slang usage.

CHAPTER 2

THE SOLAR SYSTEM AND THE UNIVERSE

You can still hear the remnants of the Big Bang.

All you need is a radio receiver. When our universe was formed from a single point in what is known as the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago, it was super-hot. It has been expanding outwards and cooling ever since and, although space is now very cold, there is still leftover heat – known as the cosmic microwave background (CMB) – which can be detected by microwave telescopes as a glow pervading the whole sky. Unfortunately, it can’t be seen by the naked eye because it is so cold, a mere 2.725 degrees above absolute zero (–273.15° Centigrade), but you can hear it, a genuine echo of the Big Bang. In 1964 astronomers Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson were using a radio antenna to measure signals from space and were puzzled by a sound they thought at first was just interference. But it was coming uniformly from all over the sky. They had detected the CMB and it won them the Nobel Prize for physics.

* * *

There’s something missing from our universe. Well, it’s not missing but we can’t find it. Yet. Cosmologists have realised that all the stuff we can see in space, such as galaxies, is only a fraction of the mass of the universe. Something else is filling the gaps. We can’t see it but we call it dark matter because it doesn’t emit or absorb light. Its close cousin is called dark energy, which is causing the universe to expand faster, almost like the opposite of gravity. Dark matter matters because without it the universe doesn’t work. It holds everything together like dough filling the gaps between currants in a bun. We know it’s there because we can see it bending light from distant stars and it stops galaxies tearing themselves apart as they spin. One day we’ll figure out what it is.

Black holes are so dense and therefore their gravity so strong that not even a ray of light can escape their clutches. Hence their name.

Neutron stars are very dense too. They are the remnants of giant stars that died in a fiery explosion known as a supernova. They have a mass of about twice that of our Sun and are the smallest and most dense stars known to exist. One teaspoon of material from a neutron star would have a mass of about 4 billion tonnes.

Our solar system is approximately 4.6 billion years old. The oldest planet is the giant blob of gas that constitutes Jupiter – twice as massive as all the other planets combined – which formed about 3 million years after the birth of the solar system.

Earth formed about 60 million years after the solar system began to coalesce (although some creationists wrongly believe that it’s only around 6000 years old).

Earth is slowing down by about 1.7 milliseconds a century. Originally a day on Earth lasted only about six hours. Now, of course, it’s 24. And the Moon is to blame. It creates the tides in our oceans, which bulge and create a twisting force that slows down the Earth’s rotation.

Asteroids up to 50 metres in diameter, with some as big as 400 metres, pass between Earth and the Moon on average about once every two years. Small ones, a few metres in diameter, pass through several times a month.

The largest asteroid yet discovered is Ceres, 965 kilometres across. It was spotted in 1801, long before many of the solar system’s planets. It accounts for more than a third of the mass of the asteroid belt that is located between Mars and Jupiter.

NASA’s DART mission to adjust the orbit of an asteroid by crashing into it (useful if it is on a collision course with Earth) worked. In 2022 the spacecraft struck its target Dimorphos and reduced the time it took to orbit its parent asteroid Didymos, by 32 minutes.

One day on Venus lasts a whopping 5832 hours, or about 243 Earth days (which is longer than a year on Venus lasts – 225 days). Just because the planet rotates slowly on its axis doesn’t mean it can’t travel quickly around the Sun.

One day on Jupiter lasts only 9 hours 56 minutes, the shortest in our solar system.

Pluto’s year is 90,520 Earth days (or 248 years), the longest in our solar system.

Venus is so inhospitable, with high temperatures of up to 475°C and an atmospheric pressure 90 times that of Earth, that when the Soviet Union’s Venera spacecraft landed there between 1966 and 1983 their systems lasted mere minutes before the probes were melted or crushed.

All planets orbit the Sun in the same direction, but Venus is the only planet that, as it does so, rotates east to west, meaning that the Sun on Venus rises in the west.

Uranus rotates on its side, appearing to roll around the Sun like a ball.

The planet with the most moons is Saturn, with 145. It recently took the record from Jupiter (which has 92) in May 2023, when 62 new moons were discovered. But new moons are being discovered all the time. Jupiter may one day top the list again.

Mercury and Venus are the only two planets in our solar system with no moons.

The Sun takes up 99.86% of the mass of our solar system. However, it is very slowly losing mass as it produces energy.

1.3 million Earths, by volume, could fit inside the Sun. That’s if you squished them up.

We know the universe is expanding because we can observe other galaxies speeding away from ours. In the same way an ambulance siren changes pitch after it passes us and its sound waves are stretched out, the same happens to light waves coming from galaxies. The waves are stretched and appear redder. The faster the galaxy is moving, the redder its light. This is known as “red shift”.

If two pieces of metal touch in space they will permanently bond in a process known as cold welding. Merely the pressure of the metals touching in a vacuum is enough. On Earth, the atmosphere will always leave some molecules of air or water between the metal pieces, but in space these aren’t present.

Sunlight takes 8 minutes 20 seconds to reach Earth.

In our solar system active volcanoes are only found on Earth and on Jupiter’s moon Io. We know there are inactive volcanoes on Venus, Mars, Mercury, and our Moon. There may be active volcanoes on Venus and Jupiter’s moon Europa, but we can’t tell because Venus has dense cloud cover and Europa is covered in thick ice sheets.

Venus is the brightest planet in the solar system with an albedo of 0.75. Albedo is a measure of an object’s reflectivity. By comparison the Earth’s albedo is 0.305. Venus is so bright because its thick, sulphuric acid clouds reflect most of the sunlight it receives.

The biggest storm in the solar system is Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, an elliptical-shaped anticyclone clearly visible on the surface of the planet, south of its equator. It has been raging for at least four centuries, has winds of up to 430 kilometres per hour and could fit about three Earth-size planets inside it. Saturn occasionally has more powerful storms but none are as enduring as the Great Red Spot. The spot does, however, appear to be shrinking.

The highest temperature on the Moon in direct sunlight can reach 120°C, the lowest at the poles and in shadow is –250°C. The lack of atmosphere means the warming effect from the Sun’s rays is intense, but this same lack of atmosphere on the Moon and in space means there is no other warming effect. Once you are in shade, the temperature plummets. Similarly, when the Sun strikes the surface of a spacecraft, its surfaces expand rapidly while the shaded sides cool and contract. This can obviously lead to potential catastrophic structural defects, and it is why spacecraft always rotate during flight.

Are we all – animals and plants alike – descended from aliens? It’s a theory, known as panspermia, that has waxed and waned over the centuries, but the suggestion is that bacteria or other microscopic life forms that evolved elsewhere in the universe could have been carried to Earth on meteorites, space dust, asteroids, and comets before evolving into higher forms of life. It’s now a subject of serious scientific research. It seems microscopic organisms can survive the collisions necessary to be ejected from their host planet, travelling through the vacuum of space, and the impact of striking another planet. Which means your great-great-great-ancestor might have been a cold virus from the Andromeda galaxy. That’s nothing to be sneezed at …

The first person to suggest the theory of panspermia was the 5th-century Greek philosopher, Anaxagoras. In the 20th century, to much scepticism, British astronomer Fred Hoyle and his protégé Chandra Wickramasinghe were modern-day proponents of the theory. Wickramasinghe would later prove that some interstellar dust was organic. Both believed that life forms continue to enter our atmosphere, giving rise to new diseases. Cue more sneezing …

Around two-thirds of the atoms in human bodies are hydrogen atoms that are almost as old as our universe (13.8 billion years old). However, hydrogen is very light, so this only accounts for about 10% of our mass. Most of the rest of the atoms in our bodies – mainly oxygen and carbon, but also including elements such as magnesium, nitrogen, calcium, and sulphur – were created inside stars by nuclear fusion reactions.

MYTH BUSTING

Myth: Space is a vacuum.