28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

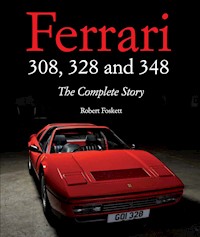

Ferrari 308, 328 and 348 traces the complete story of the four models of Ferrari's V8-powered sports cars between 1973 and 1995 - the cars that broke Ferrari out of the V6 and V12 moulds, with the V8 becoming Ferrari's most popular engine choice in the final decade of the twentieth century. The book covers the history and development of Ferrari's new V8 engine, and the 308's daunting role as successor to the popular Dino. There are specification tables and production figures for the model variants, along with details of concept cars and other related models, and a review of competition exploits. The book also considers the cars' current position in the classic car market and offers insight into the rewarding ownership experience each of the models now represents.The book covers: design processes and styling by Bertone and Pininfarina; concept cars and rivals; the cars in competition; owning and running the cars today. With a guide through the entire lifespan of these exciting V8-powered sports cars and superbly illustrated with 295 colour photographs, this is essential reading for the Ferrari aficionado.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 376

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Ferrari

308, 328 and 348

The Complete Story

Robert Foskett

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© Robert Foskett 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 886 8

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks go to everyone who has assisted in the production of this book: the many Ferrari enthusiasts who have been so generous with their time and their knowledge, and not least for their agreement to allow me to publish their superb photographs. In particular I must express my appreciation to those who extended courtesy and hospitality as they took time to educate me about their own specialist subjects, and for their invaluable knowledge, so freely shared. I must thank in particular Tony Worswick, Andy Garrett, Bryan Sherwin and Richard Davis.

My appreciation goes also to Paul Gough for his unflinching efforts in cleansing the text of so many errors, and to John Dickens, for invaluable editorial input, super photographic content, and his eloquent owner’s insight. Grateful thanks to Letizia Benzi, for her kind assistance in securing support from Italian sources. Thank you to my family and friends for their support, especially those press-ganged into interminable visits to Italian car events at showery Brooklands or windswept Silverstone: I am most grateful for your encouragement and tolerance! And of course to my children Olivia and Joseph, who offer inspiration and encouragement in everything I do.

Hot Wheels and associated trademarks and trade dress are owned by, and used under license from Mattel, Inc. © 2013 Mattel, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Mattel makes no representation as to the authenticity of the materials contained herein. All opinions are those of the author and not of Mattel.

All Hot Wheels images and art are owned by Mattel, Inc. © 2013 Mattel, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

CONTENTS

Introduction

CHAPTER 1

A BRIEF HISTORY OF FERRARI

CHAPTER 2

THE MID-ENGINE REVOLUTION

CHAPTER 3

THE 308GT4

CHAPTER 4

THE 308GTB AND 308GTS

CHAPTER 5

THE FUEL-INJECTED 308

CHAPTER 6

THE 2-LITRE AND TURBOCHARGED RELATIVES

CHAPTER 7

THE 4-VALVES

CHAPTER 8

THE 348

CHAPTER 9

SUCCESSORS

CHAPTER 10

MARKETING AND SALES

CHAPTER 11

ON TRACK

CHAPTER 12

ACCESSORIES AND MODIFICATIONS

CHAPTER 13

BUYING AND OWNERSHIP

Index

INTRODUCTION

More words must have been written about legendary Italian sports- and race-car constructor Ferrari than any other maker – indeed perhaps more than every other marque combined. Enthusiasts voraciously devour information about the capable, beautiful, exceptional cars that hail from that tiny factory in Maranello, many hoarding anything and everything related to the marque, absorbing every fact and any rumour or myth, better to understand the object of their affection – and sometimes their obsession. Even sports-car fans who proclaim indifference to Maranello’s mystique can usually be made, grudgingly, to accept that Ferraris are far from ordinary, and are certainly worthy of respect.

Part of the reason for holding Ferrari in this elevated level of esteem must be the near-legendary history of the marque. It was created by upstart race driver and ex-racing team manager Enzo Ferrari who, having learned his craft at dominant Alfa Romeo, turned against them in the area of Grand Prix racing, eventually to best his former employer with cars bearing his own name. And the iconic drivers who raced Ferrari’s wonderful machines sometimes gloried in their superiority, as others laboured heroically to overcome inferior – yet usually still magnificent – machinery their creator would never accept could possibly be second best on the track. Even today, Ferrari cultivates mystery, giving little away about who or what or why with respect to the design and development of their cars or their racing: strategic decisions and exceptional deeds were shrouded in intrigue and secrecy worthy of a cold-war thriller.

328GTS. PAWEŁ SKRZYPCZYŃSKI

Three generations of Ferrari’s two-seat V8s at Brooklands Museum. JOHN DICKENS

308GT4: note the driving lamps hidden beneath the car’s front grille.

The road cars draw by association glamour and a hint of mystery, each a desirable piece of mobile sculpture, sometimes outlandish, sometimes classical, but always impressive. No wonder drivers of Ferraris soon discover that their cars can cause a minor sensation, strangers striking up spontaneous conversations, asking for photographs, or even to sit and dream in the driver’s seat. This is no surprise: each new model Ferrari in turn represents to many enthusiasts the pinnacle of sports car design and engineering, and the relative rarity imposed by the process of careful, labour-intensive construction, and as an outcome the elevated price tag, serves only to reinforce the cars’ desirability. No wonder that attaining ownership represents for many the ultimate dream, a symbol of achievement, of taste, of success.

Happily, older Ferrari models in general buck the typical automotive trends as they age by remaining eminently desirable. They usually assume instant classic car status, rather than falling into the inevitable unpopularity of more mainstream motors, enthusiasts appreciating them with the gusto – and often the florid language – of art lovers. Designs are soon considered influential, even iconic, and while the cars fall short of the outright pace of their modern equivalents, they remain exciting to drive, challenging and rewarding, each a true thoroughbred despite its advanced years.

So while older Ferraris are still fully capable of attracting an audience and fulfilling an owner’s enthusiasm, happily many models can be had for a fraction of the cost of a brand new equivalent. If chosen carefully, they can be surprisingly cost effective to own and run. The subjects of this book, the earliest series of V8 sports cars, are some of the best examples of just such Ferrari models. Quite affordable – in comparison to other Ferrari models, at least – yet eminently capable of delivering all the fun that the best of Maranello’s models can offer, today they are attainable Ferraris, a dream that can be achieved without breaking the bank.

The families of cars in this book differ in their aesthetics, in their role, and in their level of performance, and while outwardly there is little to link the earliest Dino 308GT4 with the final 348, nevertheless they share many similarities – not least the V8 engine, recognizably the same basic design, albeit having benefitted from continuous evolution. But just as important is a characteristic that connects the tube-framed cars with the semi-monocoque models: that of a relatively non-technical approach to their design and construction – an approach that eschews active suspension or advanced aerodynamics, that avoids 5-valve heads or complex electro-hydraulic gearbox technology, even power steering – a design ethos that embraces relative simplicity.

1989 328GTS. STEVE BAMBER

Inviting 348ts interior.

This is the key that defines the experience of ownership of all these cars, from the 308, through its 328 evolution and on to the polished 348. Each model is capable of being understood, maintained and repaired by a technically literate motor enthusiast, and without the backing of a substantial bank balance. There is no magic in the engineering, and whether an owner chooses to dirty their hands or not, that simplicity permeates other aspects of ownership. It is a characteristic that shines through not only in the workshop, but also on the road, giving an ‘analogue’ driving experience, a simplicity that connects the driver with the engineering, and if mastered, allows the driver really to feel ‘at one’ with their car.

So here are four models that share so much, but are visually so distinct: first the GT4 with its curiously dated edginess, courtesy of space-age specialists Bertone, which after a period in the desirability doldrums has more recently been reappraised as a masterclass in 1970 modernism. Then the classically elegant 308 by Pininfarina, with its instantly familiar sculptural styling and often cited as the most beautiful Ferrari ever. Its successor, the 328, is a 308 ‘plus’, with more performance, more refinement, more dependability and more usability. Finally the 348, an efficient, competent Ferrari that could be used every day, blending all the benefits of Fiat Group influence in construction with even greater performance than any previous small Ferrari.

As different as they are, many characteristics bring these four together: each is a desirable ownership prospect, affordable to buy and relatively straightforward to maintain, courtesy of that unsophisticated engineering. All of them are capable of dynamic excitement of the highest order, whether on road or track, and eminently capable of satisfying even the most demanding performance driver. This is a fabulous selection of cars, each model absolutely a true Ferrari: the 308, 328 and 348.

308GTB Quattrovalvole. JOHN DICKENS

CHAPTER ONE

A BRIEF HISTORY OF FERRARI

Scuderia Ferrari came into existence on 1 December 1929, to operate as Alfa Romeo’s factory-sanctioned racing team. This small but highly professional ensemble was entrusted with the honour of preparing Alfa Romeo’s P2 Grand Prix cars and a selection of 6C cars, in 1500 and 1750cc guises. It was also perfectly placed as the trusted factory partner to race prepare Alfa Romeos for wealthy private clients. In those early days, Enzo Ferrari quite literally lived over the shop, his race-preparation premises featuring an upper floor with a large balcony, where he set up home with his wife Laura.

The birth of his son Alfredo in 1932 was a momentous occasion, an event that would impact profoundly on the future of this ambitious racing driver, and would have equally dramatic repercussions on the factory that bore his name. New-found responsibility for his beloved son Alfredo – nicknamed Alfredino, thereafter often shortened to Dino – caused Ferrari to retire completely from the dangers of his now sporadic competition driving assignments, and to focus instead, with absolute intensity, on the management of his Modena-based fledgling racing stable.

Having himself been a racer, first for minor Italian manufacturer, CMN, then from 1920 with his beloved Alfa Romeo, Enzo Ferrari had learned how to motivate and manipulate the racing drivers in his team. But his influence extended far beyond driver coaching: Ferrari had a valuable knack for enticing the most capable people to collaborate with him – for example, while at Alfa Romeo, he had persuaded legendary engineer, Vittorio Jano, to defect from Lancia, a managerial feat rewarded richly with the many successes accrued by the dominant Alfa Romeo P2 Grand Prix car that Jano went on to create. Success followed success as Ferrari managed Alfa Romeo’s factory team: wins in Grands Prix, on the arduous Mille Miglia and breakneck Targa Florio races made the ‘cavallino rampante’ (‘prancing horse’) emblem synonymous with Alfa Romeo’s victorious racers.

The iconic Ferrari script, barely altered since 1946. JOHN DICKENS

But with war looming again, Alfa Romeo decided to bring their racing efforts in-house, and Ferrari soon found his new appointment as Director of Alfa Corse constricting. In 1939 he left Alfa Romeo to retake control of his own destiny, famously explaining ‘I’m keeping my bad habits and going back to my home town’ as he returned from bustling Milan to Modena, determined to make a new start.

Despite his new-found independence, Ferrari was not free in every sense, in that his settlement with Alfa Romeo prevented the eponymous naming of any cars he might devise for a period of four years. Even so, his automotive creativity would not be denied, and within a few months he had created a new car, and named it the Auto Avio Costruzione 815. Pragmatically constructed, the touring-bodied 815 was based on a cleverly re-engineered Fiat chassis powered by a 1.5-litre straight-8 motor, imaginatively borne out of a pair of recycled Fiat 4-cylinder engines. However, development of this promising new car was curtailed as World War II broke out: Allied bombing raids motivated a move to Maranello – a sleepy village that was home to just 600 people – and Ferrari’s factory then spent the hostilities engaged in building aeroplane engines and engineering equipment. Ferrari’s facilities by no means survived the war unscathed: his new factory was bombed twice before Italy surrendered to the Allies, but it remained viable and operational as hostilities concluded.

From small beginnings: Ferrari’s first solo foray into sports-car construction, the Auto Avio. JONATHAN TREMLETT

Ferrari 166 Inter. Ferrari’s first road and race cars powered by the V12 engine design. Initially of 1.5 litres, capacity was soon increased to 2.0 litres, making sense of this model’s designation. JONATHAN TREMLETT

The First Ferraris

Business soon flourished as Italy set to the task of rebuilding itself. Ferrari’s machine tools were much in demand, but thoughts of racing cars never left Ferrari’s fertile imagination. Alfa Romeo’s edict preventing Ferrari from fielding racers bearing his own name had expired as war raged, and now Scuderia Ferrari could be reborn: this time the cars that this famous stable would use to compete on the world’s stage would be unambiguously badged as Ferraris. Lofty ambition meant that this time, recycled Fiat components were unfitting, and Ferrari’s post-war efforts would be centred on a brand new engine, created by ex-Alfa Romeo engineer, Gioacchino Colombo. A V12, no less, would be installed in the first true Ferrari racer, the 1500cc 125 of 1947, a magnificent little machine that would prove victorious in only its second race.

Ferrari’s upstart would go on to win seven of the fourteen races in which it was entered that year, and the following year the engine received a stretch to 2000cc to power Ferrari’s evolution racer, the 166. This car won the Mille Miglia in 1948, and the following year grabbed the international limelight for the fledgling manufacturer by winning both Le Mans and Spa 24-hour races, astonishing successes at the highest sporting level for a marque barely two years old. The Scuderia’s first victory in Formula 1 arrived the following year, as Gonzales took the chequered flag at the British Grand Prix.

Road Cars

While the factory racers aspired to victory at the highest level, so ambitions grew for the road-going models Enzo Ferrari often suggested existed only to fund his team’s racetrack endeavours. Hand built in tiny volumes, the 166 and its successor the 195 would barely reach a production run of sixty cars in four years, but they whetted the appetite of the resurgent sports-car market for further Ferraris. Factory output doubled with the introduction of the 212 Inter, with eighty made in two years, but it would not be until 1955, with the introduction of the 250 Europa GT, that Ferrari at last would make road cars in meaningful numbers. While by no means mass produced, the Pininfarina-styled coupé could finally be offered to more discerning customers, and Ferrari’s reputation as the purveyor of performance cars for the road would approach that of the racing team.

One of the most beautiful of Pininfarina’s collaborations with Ferrari, the 250GT Lusso. STEFAN KOSCHMINDER

This early collaboration with Pininfarina would be the start of a long and fruitful partnership, as the famous carrozzeria gradually came to dominate road-car design at Maranello for almost two decades. The image-building 250 models would continue into the early 1960s, variations of essentially the same elements – engines, chassis and even bodywork – being adapted with success to both road and competition use. Many of the most famous Maranello racers could be ordered in street trim: the 250GT SWB (short-wheelbase) could be had with either lightweight aluminium alloy bodywork for the track or more durable steel for the rigours of road use. A selection of power outputs was also available for its 3-litre V12 motor.

As the early 1960s progressed it became clear that road-based race cars could no longer dominate on track, and more specialized machinery would be required if Ferrari were to continue to compete at the uppermost level, certainly in sports-car racing at such illustrious venues as Le Mans or Daytona. And so Ferrari’s road cars began to diverge from their competition-focused stablemates. Fast, comfortable, front-engined grand tourers became the order of the day, built in ever greater numbers – by 1965 the factory was producing 600 cars each year. Maranello’s road cars may still have shared a factory, a name and an evocative emblem with the Scuderia’s racers, but they now had relatively little in common with the mid-engined projectiles the competitions division fielded in the pursuit of glory. But the link between race and road car was not permanently broken: as the 1970s drew near, so road car designers, eager to provide enthusiast drivers with the most dynamic performance possible, began to look to the track for fresh mechanical inspiration.

FERRARI NUMBERING – DECIPHERING THE DIGITS

With a handful of exceptions, including the Lancia-derived Grand Prix designs campaigned between 1955 and 1957, few of Ferrari’s cars – either competition or road-going models – have been formally named, most being referred to by model number only. While some of the numbers selected as designations may appear random, they are generally descriptive and decipherable.

In the early days cars tended to be numbered in recognition of the cubic centimetre capacity of a single cylinder: a 250GT V12 motor therefore of 3 litres total capacity, and a 500 Testa Rossa from 1956 featuring a 4-cylinder 2-litre motor. From 1957, with the arrival of the Dino Formula Two racer, a new numbering scheme would come into effect, whereby the capacity of the engine in litres would prefix a number representing the count of its cylinders. So the 246 F1 Grand Prix car used by Mike Hawthorn to win the World Driver’s Championship in 1958 was propelled by a 2.4-litre V6 unit.

Confusingly, both numbering schemes ran in parallel for some time, the latter gradually gaining favour through the 1960s and 1970s. In 1981, with the turbocharged 126 Formula 1 racer, the competition cars abandoned the traditional numbering convention for good. Through the course of this decade, some of the road cars began to acquire names rather than numbers: Mondial and Testarossa were two early examples, and the F40 was christened in celebration of the fortieth anniversary of the company’s foundation.

Three-point 2 litres and 8 cylinders, indicated by Ferrari’s descriptive numbering scheme. PAWEŁ SKRZYPCZYŃSKI

More recently, numbering has become less standardized. Both 360 Modena and F430 model designations explain their respective 3.6- and 4.3-litre capacities but not cylinder count, while the earlier F355 was more meaningfully – if not consistently – numbered in recognition both of a 3.5-litre capacity and in the number of valves per cylinder its motor design featured. And the recent 612 Scaglietti may be a 12-cylinder car, but its capacity is 5.7 rather than 6 litres.

CHAPTER TWO

THE MID-ENGINE REVOLUTION

Ferrari was by no means the only iconic motor-racing constructor to write the opening chapter of its legend in 1946. In the same year that Colombo was hard at work creating Ferrari’s magnificent V12 engine, a small garage in Surbiton, Surrey, became the somewhat unlikely base from which Charles Cooper and his son John began work on a diminutive racing car, its small size belying its importance in terms of the future of Grand Prix racing. Cooper’s tiny 500cc JAP motorcycle-engined racer was mid-engined.

Mounting the powerplant behind the driver was certainly not a new idea: Porsche had chosen this layout for the mighty Nazi-backed AutoUnion Grand Prix cars of the 1930s, but it was a tricky layout to make work well with primitive tyres and unsophisticated suspension. Nevertheless, Cooper found a way to make it work, and work beautifully, in a series of successful Formula 3 and Formula 2 racers, as the concept of small racing cars featuring mid-mounted engines became synonymous with Cooper Cars. And when the same formula was tried in a Grand Prix racer, the results were startling.

Winning two races in 1958 against resolutely front-engined competition, Cooper proved the concept was viable in the modern era, and in the following year, Jack Brabham would become the first Formula 1 World Champion to win the title driving a mid-engined Grand Prix car. The far-sighted team proved that the feat was no fluke when they repeated their successes the following year. But not everyone was enamoured of the mid-engined revolution: Enzo Ferrari disliked the concept and shunned Cooper’s lead wholeheartedly until 1961. By then it was inevitable that all teams would emulate Cooper’s efficient concept, and since 1959, every Formula 1 World Champion has preceded his engine across the finish line.

Ferrari’s future, as imagined by Marcello Gandini. BERTONE HISTORICAL ARCHIVE

1958 Ferrari Dino 246 Grand Prix car. SIMON HODSON

Conveniently, the Scuderia’s scramble to emulate Cooper’s racers was greatly simplified by the ready availability of a compact motor design ideal for the mid-engined template. Ferrari’s Grand Prix cars had been powered by the dependable V6 Dino engine since the retirement at the end of 1957 of the Lancia-Ferrari D50s, entrusted to Ferrari by Lancia’s race team on their withdrawal from competition. The Dino engine, and the cars into which it would be installed, were named in honour of Ferrari’s son who had died in 1956, a tribute that would continue in the naming of every V6-powered Ferrari until the advent in the 1980s of new, turbocharged Grand Prix engines of the same configuration.

Dino Ferrari was said to have participated in design work for the engine alongside Ferrari engineering stalwarts Massimino and Jano, the three collaborating to devise an engine bound at first for Formula 2 racing, but with the potential to be developed into a whole dynasty of smaller capacity Ferrari motors. The Dino motor would soon see service in Formula cars, sports racers and even an extended family of road cars, the first iteration ready for use in a 1957 Formula 2 Ferrari. This much admired motor would subsequently serve to excellent effect in the Scuderia’s Grand Prix racers from 1958 to 1963, initially installed ahead of the driver, though later switched to a modern mid-mounted location. The motor saw mid-mounted service in numerous Ferrari sports racers, including the 1962 Dino 246SP and the smaller, 2-litre capacity 196SP.

Often overshadowed by the larger sports cars of the day, including Ferrari’s own 330P3, the Dino racers were nevertheless highly successful in competition, particularly at circuit events such as the Monza 1,000km, on the roads that comprised the Targa Florio route, and even in international hill-climbing events.

By the mid-1960s, the mid-engined revolution was in full effect at Ferrari. Not only were the Grand Prix cars now by default constructed in this layout, the Scuderia’s big sports racers were also cast in the same mould. The Testarossa was replaced in 1963 by the accomplished 250P, a 3-litre V12-powered prototype, which won at Le Mans and twice more to take three out of four of that season’s world sports-car races. The cars fielded in the GT racing class soon followed suit, though not without some delays in homologation caused by the 250GT LM’s lack of similarity to the 250GT on which it was supposedly based – rather the mid-engined GT was far closer in design to the dominant 250P. Later cars featured a bigger 3.3-litre engine, the 275 LM in 1965 giving Ferrari their most recent Le Mans win to date. In lesser race series, Dino lineage continued through 1965, with 1.6- and 2-litre models, the 166P and 206P followed by the 206S, all of them sharing similarity in appearance – if not in specific line or detailing – to the Dino road cars already in development at Maranello.

A Race Car for the Road

The Lamborghini Miura

While Ferrari presented race cars and concepts featuring mid-mounted motors, rival manufacturer Lamborghini determined to raise the stakes on the road. At Turin in 1965, Ferrari’s rival presented a nearly production-ready bare chassis of such ambition that all current high-performance road cars were instantly rendered obsolete. The Miura’s monocoque substructure, designed by Gianpaolo Dallara and Paolo Stanzani, proudly carried its engine behind the cockpit: the lengthy but narrow transverse-mounted 4-litre V12 nestled hard against the bulkhead, enabling Lamborghini to package a 1,090mm (42.9in) long motor within a compact 2,504mm (98.6in) wheelbase.

Its installation was beautifully conceived: the gearbox sat beneath the motor, and validating Issigoni’s innovative packaging for the Austin Mini, the engine and gearbox shared oil. Even the differential unit was located to the rear of the same casting, perfectly positioned at the car’s centreline, so the driveshafts could be equal in length.

An early Ferrari attempt at a mid-engined sports car, the 250GT LM. JULIAN BOWDIDGE

Lamborghini’s groundbreaking, beautiful Miura, first of the mid-engined road-going supercars. JONATHAN TREMLETT

The bodywork fitted to Lamborghini’s clever chassis was no less startling: twenty-five year old Marcello Gandini’s stunning design for Carrozzeria Bertone receiving a rapturous reception when unveiled at Geneva in March 1966. Somewhat reminiscent of contemporary mid-engined racers of the period, especially the GT40, the Miura was sculptural – low and lithe, and elegantly detailed. Perhaps most importantly, the car’s relatively short nose and balanced proportions emphasized its radical mid-engined configuration.

The effortlessly stylish appearance and apparent simplicity of the Miura belied frantic engineering turmoil in the factory as Lamborghini’s designers slaved to solve problem after problem and make their ground-breaking supercar viable. There were vibration problems to overcome as various solutions were tried for feeding power into the gearbox – in the end an idler gear between crank and gearbox provided the solution, though it necessitated a minor redesign of the engine so the crank would spin in the opposite direction and thereafter turn the driveshafts the correct way. Achieving an acceptable and reliable gearshift forced a redesign of the crankcase, so the shift could pass right through it just beneath the crankshaft. Heat build-up in the engine bay meant a polycarbonate rear window had to give way to the slats that are now a core element of the Miura’s iconic design.

The end result certainly justified the effort. The mid-engined Miura was a revolutionary – and headline-grabbing – reimagining of the ultimate sports car for the road. Here was a new template for the modern high performance car, one that even conservative Enzo Ferrari would be forced to adopt – this despite his wariness at the prospect of inexperienced and under-skilled drivers being let loose in really high performance cars that featured challenging mid-engined handling characteristics, such dangerous territory previously the preserve of the professional racing driver.

THE GRAND PRIX DINO

Ferrari first began experimenting with a mid-engined layout for the Grand Prix cars during the 1960 season, when a prototype 246 Dino appeared alongside conventional front-engined racers at Monaco that year. The mid-engined Ferrari was immediately on the pace, finishing a creditable sixth on its first outing. Nevertheless, the team chose to focus their efforts on the front-engined cars for the remainder of the season, and work to develop the mid-engined Grand Prix concept would instead centre on a new design aligned with the incoming 1961 season’s 1.5-litre formula.

Ferrari’s beautiful 156 Dino, often referred to as ‘Sharknose’ in reference to distinctive twin-nostril air intakes feeding the front-mounted radiator, would represent Ferrari in the World Championship throughout 1961. Meeting new regulations, a new engine design of 1.5-litre capacity was fitted. As with previous Dino Grand Prix cars, it was a V6, heavily based on the preceding 246 Dino motor. Curiously, two versions of the motor were produced for use in the 156, each featuring a different V angle: some cars raced with a 65-degree variant, others were propelled by a 120-degree low-line version. The 156 Dino achieved fame as the car that Phil Hill piloted to the Formula 1 World Driver’s Championship in 1961, and notoriety in the same year, as the car in which Wolfgang von Tripps crashed and perished at Monza, killing fourteen spectators in a horrific accident.

Despite the tragedy of Von Tripps’ death, tolerated at the time as an inevitable, almost intrinsic feature of motor racing, Ferrari should have been ready to follow up the World Championship with repeat success in 1962. But it was not to be. Following a dispute that saw many of Ferrari’s most senior managers leave the team, the Scuderia suffered perhaps their most disastrous racing year of all time, withdrawing before the end of the season. Nevertheless, they regrouped around a new car design for 1963. Though different in many details, with a new simple oval radiator intake, six-speed gearbox and revised body, the 156 was still recognizably a descendant of the successful 1961 car, even wearing the same wire-spoked wheels – the last Grand Prix Ferrari to do so. Results were similarly reminiscent of the earlier cars, the revitalized Dino delivering wins for John Surtees in a successful, if not World Driver’s Championship-winning season.

Chris Rea in a 156 ‘Sharknose’ Grand Prix car, Goodwood Festival of Speed 1995. ANTHONY FOSH

The Ferrari Prototypes

While Lamborghini laboured to make the Miura a practical production prospect, Ferrari and Pininfarina were hard at work together, shaping a similar concept, albeit on a slightly more modest scale. One of Ferrari’s tiny 206P race cars was selected for a makeover and given a swoopy new berlinetta (coupé) body to become the Dino Berlinetta Speciale. This influential Ferrari, introduced to the public at the Paris Salon in 1965, would give motoring enthusiasts their first glimpse of a possible mid-engined road car from Maranello. While the Speciale was clearly the forerunner of Ferrari’s Dino production cars, this first iteration was far from production ready. Details including the impractically low-slung roofline and vulnerably low-set headlamps would give way, in a second prototype shown at the Turin Show in 1966, to a more production-feasible shape, the second car’s bodywork subtly shifted to achieve more practical proportions.

Ferrari’s Dino prototypes were not the only mid-engined musings emanating from the Maranello factory at that time: a big GT, the 365P 1966 three-seater Berlinetta, also appeared at the Turin show, this ‘full-size’ Ferrari body shape very much hinting at the design of the soon-to-arrive production Dino. While the standout feature of the car was its unusual three-seat cabin, with the driver seated centrally, there were many other details to signpost the direction Ferrari would be taking as the mid-engined road-car revolution gathered pace. Its unadorned haunch air intake in particular was very close to that featured in the finalized Dino design, lacking as it did the aluminium strip that bisected this vent on both iterations of the smaller prototype.

The 365P also wore a most remarkable set of alloy wheels of a modern and minimalist stylized five-pointed star-shaped design, the edges of each spoke framed with a squared-off raised border. While the 365P proved to be a design cul-de-sac in terms of future V12 model designs, those wheels would be adopted across the range, becoming a motif synonymous with Ferrari design through the next two decades.

Ferrari customers would have to wait until 1968, a full three years from the introduction of the Dino prototype, until a mid-engined road car could actually be bought from the factory. True, a 250 LM in road trim had been shown at Geneva in 1965, but that was a disguised racer and not a car purpose-designed for highway use. Finalized for Turin in 1967, the space frame and alloy-bodied masterpiece, designed by Pininfarina and constructed at Scaglietti, would begin to trickle out of the factory the following year, and while the 206GT Dino was certainly a close relative of the cars that had adorned Ferrari’s show stands in the past three years, there were significant differences. Unlike the previous design studies, the production car would carry its V6 motor transversely, like Lamborghini’s Miura, the engine attached to a new transmission design whereby a single casting formed the gearbox case and engine sump. Although road-going Dino engines would grow in capacity and cylinder count in the coming years, this mechanical layout would persist as the definitive template for smaller Ferrari models for more than twenty years.

Dino prototype by Pininfarina, permanently displayed at the Le Mans 24 Hours Museum. PAUL AND KELLY GERRARD

Just 152 cars would be built before the Dino design received a comprehensive overhaul, partly in response to the strong performance available from Porsche’s competing 911S, but also to facilitate larger-scale production of the largely hand-built car. At Geneva in 1969 Ferrari unveiled the 246GT, visually near-identical to its predecessor, but similarity belying a radical refactoring. Longer in both wheelbase and length, and wearing bodywork of steel not aluminium alloy, at 1,080kg (2,381lb) the new Dino was heavier by a full 180kg (397lb) than the earlier car, though greater power would compensate for the beefier build. The 246GT would receive a new variant of the Dino motor, designed to work as well in a Fiat as in a Ferrari. The revised unit was no longer of all-alloy construction, but now based on an iron block, specified in the interest of larger-scale production. It was enlarged to 2419cc, achieved through use of larger bores and longer stroke, for a worthwhile increase in power to 195bhp, and perhaps more importantly for driver satisfaction, a good deal more torque.

Tribute to a lost son: Ferrari’s Dino GT.

The 246GTS

The popular Dino GT was soon joined by an open-topped car. Arriving at the 1972 Geneva Show, the 246GTS, as it would be designated, was not a full spider design, instead featuring a lift-out roof panel, very similar to the arrangement installed in the Dino GTS’s arch rival, the targa-topped 911. Thereafter, and until the advent of the 348 Spider more than twenty years later, the smaller-engined two-seat Ferraris would mirror the Dino model range, each successive model offered first as a berlinetta and then as a GTS equivalent, featuring a lift-out roof panel.

While collaboration with Fiat had made the Dino project a viable proposition for Ferrari, also facilitating its engine’s use in Formula 2 racing, even greater dependence on Fiat was on the horizon. Motivated to ensure a future for the company that bore his name, Enzo Ferrari entertained the possibility of a Ford takeover in the early 1960s. Though he subsequently had a change of heart, the idea of finding a safe haven for his beloved marque persisted, and in 1969 the tiny, race-obsessed firm was subsumed into the Fiat Group, though Ferrari himself retained a significant shareholding, and critically retained absolute control over the competition division.

Under Fiat Group stewardship, Ferrari completed the transition to mid-mounting of engines in the range’s highest performing cars, with the arrival of the 365GT4 Berlinetta Boxer. This flat 12-powered supercar, first shown at Turin in 1971, was a belated response to Lamborghini’s Miura, its showroom arrival tactically delayed until 1973 as a result of the outgoing Daytona’s continued sales success. The Berlinetta Boxer was clearly an evolution of Pininfarina’s earlier work on the Dino, more modern in its detailing and almost complete lack of chrome work, radiator grill apart. Here was a car that was truly contemporary and looked it, a genuine mid-engined supercar and a really modern Ferrari.

THE DINO FAMILY

Entry to the 1967 Formula 2 race series was dependent on the use of an engine limited to 1.6 litres capacity, and based on a volume-produced design. These regulations had been designed to encourage the use of adapted road-car engines instead of expensively engineered, all-out race designs. Although Ferrari clearly had the expertise to create such a motor for its team, it was by no means certain that the factory could series-produce them in the required volume, and so an expedient deal was struck with Fiat: Ferrari would develop the engine in two formats, a 1.6-litre design for the track, and a 2-litre unit for the road, to be installed in flagship Fiats as well as Ferrari’s own offerings.

The magnificent new motor was designed by Franco Rocchi, and tweaked for production by engine design legend Aurelio Lampredi, the man responsible for the V12 design that replaced Colombo’s original unit, in Ferrari’s esteemed 250GT range. The newest Dino motor would share the same 65-degree V6 of earlier designs, this unusual angle selected to allow sufficient space within the V for nrestricted intake breathing. Unlike the previous Dino engines that had been reserved for the racetrack, a 2-litre version of this mechanical masterpiece would soon become more widely available than any Ferrari motor had been before. Formula 2 regulations dictated that at least 500 enthusiasts per year must have the opportunity to own a Ferrari-engined car, and so the motor began to feature in a selection of Fiat Group offerings.

Fiat’s pretty Dino Spider. PETER KABEL

Fiat couldn’t wait to show their Ferrari-powered sports cars. At Turin in 1966 they presented both the elegant Bertone coupé and the sporty Pininfarina spider. Both models used adapted Ferrari engines, achieving a claimed 160bhp rather than the 180bhp of the same unit installed in the Ferrari Dino. In reality, the only differences between Fiat and Ferrari motors were in carburettor jetting and exhaust pipework; perhaps the more modest Fiat claim was a courtesy to uphold Ferrari’s honour. The Dino V6 was mounted up front and longitudinally ahead of a five-speed gearbox in both Fiat models.

Both cars were underpinned by an adapted Fiat 125 platform, the two-seat spider on a compact 2,280mm (90in) wheelbase, the plus-two coupé a longer 2,540mm (100in). Promising double-wishbone front suspension was partially undermined by an archaic semi-elliptic leaf-sprung rear set-up, though contemporary road-testers found the road-holding of these early Fiat Dinos very satisfactory. In step with Ferrari’s Dino, both Fiats received the larger 2.4-litre motor in 1969, the so-called 2400 Dino models now quoted as achieving 180bhp against Ferrari’s 195bhp, and sporting improved semi-trailing arm independent rear suspension.

Bertone-designed Fiat coupé.

Sadly, despite the cachet of its Ferrari motor, fewer than 8,000 of Fiat’s excellent Dinos would be built, and the range was quietly discontinued in 1973.

But that was by no means the end of Ferrari’s inter-marque collaboration, because an innovative, audacious new home had been found for Ferrari’s compact motor. Originally conceived as a theatrical, Fulvia-based show car, the Lancia Stratos concept had been reworked at the insistence of Lancia’s competition manager Cesare Fiorio, to replace the ageing Fulvia as Lancia’s next rally weapon. By now Lancia was an autonomous element within the Fiat Group, and as Fiorio surveyed the Group for a suitable motor he spied the Dino V6, an ideal choice. Despite wrangles within the Fiat Group, the motor was eventually approved for use in the Lancia in 1972, though it took a dalliance with Maserati around potential use of their Bora V8 to unblock Ferrari’s resistance to the idea.

With breathtakingly taut, angular bodywork designed by Gandini for Bertone, the Stratos was incredibly compact: its wheelbase was just 2,180mm (85.8in), and the entire car an astounding 480mm (18.9in) shorter than the dainty Dino 246GT. Initially campaigned as a prototype, the Stratos was soon winning for Lancia, scoring its first victory in the 1973 Firestone Spanish Rally. Once the Stratos was homologated in October 1974, somewhat dubiously by including part-completed cars in the count of the required 400 units, the Stratos was soon established as a rally sensation. This unfeasibly rapid wedge enabled Lancia to secure three back-to-back world championships between 1974 and 1976, after which Lancia withdrew from front-line rallying.

But despite its advancing years and lack of direct factory support, the Stratos continued to win. In 1978 Markku Alén won the Giro d’Italia in a turbocharged Group 5 Stratos, the third time the car had won this challenging road race, and the Stratos took its last World Rally Championship victory in 1981, with its fifth win of the Tour de Corse. But in spite of its competition success, the Stratos road car was a slow seller, and it could still be purchased ‘new’ several years after production had ceased in 1975.

Lancia Stratos. JOHN DICKENS

Ferrari and the V8

While placement of power-plant would have a most dramatic effect on the architecture and design of Ferrari’s road cars, the challenge of building contemporary sports cars suited to the design-savvy 1970s market, and capable of meeting an inrush of safety and environmental regulations, meant that the marque could not rest on its laurels. New motor designs, cleaner and more powerful, would be needed to propel a new generation of more accessible and relevant Italian sports cars in the coming decade. Like so many US-based manufacturers facing the very same challenges, Ferrari opted to develop a new V8.

Popular myth has it that Enzo Ferrari felt that only V12 power was appropriate for a car bearing his name. While there are many documented quotations to confirm his enthusiasm for the configuration, especially in the earliest days of his firm, Ferrari was ambitious and pragmatic enough to accept race victories, irrespective of cylinder count. Indeed, in its sixty-plus year history Ferrari has fielded cars with a wide variety of mechanical architectures, from straight 4s to boxer 12s. The very first Ferrari road car, albeit not one bearing the Ferrari name – the Auto Avio Costruzione of 1940 – was fitted with a 1.5-litre, straight 8-cylinder engine.

The Ferrari factory’s first V8 experience would not be with a Maranello design at all. Following their withdrawal from competition after driver Alberto Ascari’s death in 1955, Lancia entrusted their innovative pannier-tank D50 Grand Prix cars to the Scuderia. Six of these Jano-designed beauties arrived at Maranello in July 1955, and with them an obligation to uphold Italy’s racing honour at the highest level. Ferrari would contest Grands Prix with their inherited V8-powered machinery until they were superseded by newer, Dino-engined Grand Prix cars as the 1957 racing season drew to a close.

Lancia D50, the first V8-powered Grand Prix car to be campaigned by the Scuderia. ROBERT KNIGHT

Just a few short years later, in 1962, Ferrari would unveil its own V8 racing motor, a unit designed by Carlo Chiti for a proposed 248GT, a car that would never materialize. But the V8 was put to use on the race track, making its debut with the NART team at Sebring in the 248SP sports racer. In its initial guise, with a capacity of 2458cc, the V8 generated 250bhp at 7,400rpm, an output that proved inadequate on track, leading to a lengthening of stroke by 5mm to 71mm. The bore at 77mm remained as before. With its new capacity of 2644cc the motor provided 260bhp, at 7,500rpm. However, despite some promise, only three were built, and the design was not extensively campaigned.

Nevertheless it would be just two years before another Ferrari V8 arrived in the pits: a new 1.5-litre motor was devised by designer Angelo Bellei in line with contemporary Grand Prix rules. The Tipo 158 was a 90-degreeV8, featuring twin camshafts for each cylinder bank, and with 64 × 57.8mm bore and stroke for a capacity of 1487cc. Output was an excellent 205bhp at a heady 10,500rpm, enough to buzz John Surtees to the 1964 World Championship, and bring a fifth constructor’s title home to Maranello. Ferrari’s radical V8-powered monocoque car was a great success, but although its competition career continued into 1965, Enzo’s beloved V12 configuration would return during the course of the season, and the victorious V8 would be permanently retired for 1966.

Dino 248SP. JOHN DICKENS

Surtees reunited with the V8 Tipo 158 at the Goodwood Festival of Speed, 2010. GRAHAM KEEN

A V8 for the Dino

Ambitions for the next generation of smaller Ferrari models, designed to replace the much loved 246 Dino range, would render the excellent V6 engine design obsolete. The challenge from larger capacity models from Porsche and others would define the new engine: it would emulate the charisma of the outgoing V6, but was bigger and could therefore provide more power – and power that was more readily accessible – for a user-friendly experience, resulting in broader appeal. Ferrari no doubt reviewed the experience gained with various V8 racing powerplants through the 1960s, as they plotted the specification for a bigger, more practical and usable Dino, better suited to the 1970s international marketplace. Thus the next in the line of compact, mid-engined cars conceived to honour Ferrari’s lost son would be powered by an all-new V8, boasting a worthwhile capacity increase to 3 litres.

In his own inimitably eloquent style, Enzo Ferrari once expounded that ‘engines are like sons: one settles down and studies, and another signs cheques and is dissolute’. Well, the 90-degree V8 designed for the larger Dino would be a motor in the studious mould, hard working and high achieving, the first example of a design configuration that would cause a realignment of the marque’s entire model line-up. Indeed since its introduction, the Ferrari range has never been without a V8-powered model, and it would not be long before the V8 range would represent Maranello’s most popular and accessible line.

Tipo 158 1.5-litre V8 Grand Prix engine. PHIL MARKHAM

While chassis and body construction for the new Dino would be outsourced, in accordance with Enzo Ferrari’s often repeated personal view that the engine was the most important element of any car bearing his name, the new DinoV8’s crankcase and heads would be cast, machined and assembled in house. Cast entirely in aluminium alloy, initially using the traditional sand-casting method, the factory soon switched to the more robust die-casting process as production was ramped up to meet growing demand. Perhaps in order to perpetuate Ferrari’s legendary air of creative mystery, no engine designer was ever confirmed, though work is usually attributed to Franco Rocchi, assisted by Angelo Bellei.

Excellent picture of the Ferrari V8 engine on display at Malaga Motor Museum, taken by Belfast journalist Gary Fennelly: an early carburettor-equipped motor featuring twin distributors. The unit attached to the nearer of the cambelt covers is the belt-driven air-conditioning compressor. GARY FENNELLY