7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

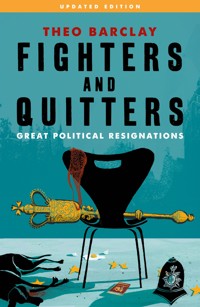

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

They say the first rule of politics is never to resign. It seems, however, that Britain's leaders have all too often failed – or refused – to heed this sage advice. Fighters and Quitters charts the scandals, controversies and cock-ups that have obliterated dreams of high office, from the ex-minister who faked his death in the 1970s, to Geoffrey Howe's plot to topple Margaret Thatcher, to the many casualties of the Brexit saga. Then there are the sex and spy scandals that heralded doom and, of course, the infamous Profumo Affair. Who jumped and who was pushed? Who battled to keep their job and who collapsed at the first hint of pressure? Who returned, Lazarus-like, for a second act? From humiliating surrenders to principled departures, Fighters and Quitters lifts the lid on the lives of the politicians who fell on their own swords.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

“Some were brought down by high-minded principle, others by basic lust. Theo Barclay details the ambition, the cover-ups and the chicanery behind many of the great resignations of modern politics – stories which seemed extraordinary at the time, and look even more bizarre in retrospect. He writes with fun and flair, and has a great future as a political historian.”

MICHAEL CRICK,CHANNEL 4 NEWS

“The dreary old saw about how political careers end deadens a truth which this book so engagingly brings to life – it falls to some in public life to fail spectacularly. The victims of their own greed, duplicity, arrogance and stupidity, these notables are sped to their doom by double-crossing call girls, scheming colleagues, persistent hacks and, surprisingly often, by just sheer bad luck. Theo Barclay charts their downfall with great wit, learning and humanity. Aspirants should read it as a warning; participants as a manual. The rest of us can simply enjoy the shiver of schadenfreude.”

FRANCIS ELLIOTT,THE TIMES POLITICAL EDITOR

“Brilliant and pithy!”

DAILY MAIL BOOK OF THE WEEK

“An incisive and entertaining canter through political misdeeds.”

JOHN PRESTON,DAILY TELEGRAPH

“Amazing stories, beautifully delivered.”

EMMA BARNETT, BBC RADIO 5 LIVE

“Elegance, panache … a sure-fire box office smash.”

DAVID SINGLETON, TOTAL POLITICS

“A superb highlights reel of unscheduled departures from Westminster.”

THE AUSTRALIAN

For my grandmothers, Marguerite and Clare

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are several people without whom this book could never have been written.

I would like to thank the following:

Olivia Beattie, Iain Dale, Bernadette Marron, Ellen Heaney and all the team at Biteback, for taking a punt on a first-time author writing an unusual book and for coping with my inability to keep to a deadline;

My father Johnny, for introducing me to the writing of A. A. Milne and Alan Bennett, and for his unceasing enthusiasm;

Georgie, my sister, for ferreting out the hidden fun everywhere – including polling stations;

Peter and Suzanne Thackeray, the formidable duo who nurtured my interest in politics;

Sam Carter, who fed my addiction to third-rate Blair-era political biographies;

Andrew Neil, for unwittingly keeping me company through many a day and night;

Geoff Steward and Nico Gaisman for their encouragement and meticulous editing;

Michael Crick, for kindly reading through the manuscript, pointing out errors and giving sage advice;

Victor Khadem, who has nurtured this book from the first idea to the final sentence;

Riversdale Waldegrave, for heroically editing the contents while hard at work; and

Lucy Fisher, for her endless help with this book and her constant love and support.

T. W. T. B.

November 2018

CONTENTS

‘We know of no spectacle so ridiculous as the British public in one of its periodical fits of morality. In general, elopements, divorces and family quarrels pass with little notice. We read the scandal, talk about it for a day, and forget it. But once in every six or seven years our virtue becomes outrageous. We cannot suffer the laws of religion and decency to be violated. We must make a stand against vice. We must teach libertines that the English people appreciate the importance of domestic ties. Accordingly some unfortunate man, in no respect more depraved that hundreds whose offences have been treated with lenity, is singled out as an expiatory sacrifice.’

LORD MACAULAY INCRITICAL AND HISTORICAL ESSAYS, 1851

‘A man is not finished when he’s defeated. He’s finished when he quits.’

RICHARD NIXON TO EDWARD KENNEDY, 1969

‘Age wrinkles the body. Quitting wrinkles the soul.’

DOUGLAS MACARTHUR

INTRODUCTION WHEN TO FIGHT AND WHEN TO QUIT

The first rule of British politics is never to resign. High office is not, after all, easily acquired. To climb the greasy pole, MPs must serve an apprenticeship as under-secretary for paperclips, suffer countless rubber-chicken dinners and develop an expertise in potholes to rival the most qualified highway engineer. Having endured such tiresome training, senior politicians rarely give up without a fight. In nearly three centuries of Cabinet government, fewer than one hundred cabinet ministers have quit. This book tells the story of the most dramatic of those plunges, from bunglers making unwitting errors, to ministers mired in corruption and even would-be political assassins.

The government’s ministerial code restates two commonly cited constitutional conventions that set out the circumstances under which resignation is mandatory. First, ‘collective responsibility’, which dictates that ministers must leave the government if they cannot support the Cabinet’s agreed position. Second, ‘individual responsibility’, which forces them to take the blame for their own or their department’s catastrophic mistakes. But if those conventions ever existed, both have, like the requirement for the Home Secretary to be in the room for every royal birth, been consigned to history.

A look back over the past forty years of British politics proves that the doctrine of collective responsibility has shaky foundations. Cabinet members have frequently made it clear in private and in public that their views differ from the government position. United and compliant Cabinets are not the product of a nebulous constitutional convention, but of good party management, large majorities and powerful Prime Ministers. Individual responsibility is in even worse health. It summons up an idealised image of the dutiful statesman honourably falling on their sword to prevent the faulty gears of government from being exposed. But such action is anathema to the modern politician, who clings desperately to any excuse to remain in office. Embattled ministers are only too happy to blame civil servants for their department’s problems, and members of the Cabinet have survived the most catastrophic blunders. In 1983, Jim Prior remained Northern Ireland Secretary despite thirty IRA fighters breaking out of prison on his watch, and ten years later, Norman Lamont refused to quit after his decisions cost the country £3 billion in one day. The last time a minister truly took the blame for their underlings’ errors was in 1954, when Sir Thomas Dugdale sacrificed himself in the convoluted Crichel Down Affair, in which the government was deemed to have broken its promise in a land dispute. Hailed at the time as the definitive example of individual responsibility, it appears, with hindsight, to have been an isolated incident.

When, then, will politicians resign? Instead of following a set of strict constitutional rules, they quit only if they are prompted by their own conscience, considerations of political expediency or if they are forced out by the Prime Minister of the day.

Modern-day resignations tend to follow three patterns:

The first is the daylight assassination – an aggressive, rather than defensive, move. A select number of Cabinet ministers have deployed their resignation as a weapon, an Exocet launched at the government they have left behind in a bid to destabilise it. These hot-headed pretenders usually find to their dismay, however, that nobody is willing to follow them over the cliff. The only effective exponent of the tactic was Geoffrey Howe, who succeeded in his mission to destroy Margaret Thatcher in 1990 by using his resignation to call for open insurrection. Yet even his victory was a pyrrhic one, ending not only the Prime Minister’s career but also his own.

The second kind of resignation is the principled stand – quitting solely to publicise a strongly held point of dispute with the government, eschewing all future preferment and ending one’s frontline career. This category boasts an even smaller number of quitters, despite its connotations of nobility and probity. The most celebrated is Robin Cook, whose laser-focused demolition of the case for the Iraq War in 2003 was made in one of the few speeches to the House that has outlived its maker.

Overwhelmingly, the most common route to the political scrapheap is the third type of resignation – the slow death. This undignified end follows a torrent of blows from party, press and public. The flailing minister, enmeshed in a scandal or dogged by allegations of misconduct, attempts to hold out, but eventually succumbs to the inevitable, their reputation lying in tatters.

Not all scandals result in the departure of the politician involved, but those that do tend to share certain characteristics. What is it, then, that renders an incident fatal?

Most importantly, the offence must be sufficiently grave or titillating to attract the sustained attention of the press. Ministers who are merely inept or unpopular usually manage to limp on until the next reshuffle. It is often obvious when a story will take hold, so Chris Huhne’s frontbench career was incompatible with his designation as a criminal suspect and, later, Andrew Mitchell could not survive accusations that he had called a policeman a ‘pleb’. Such sagas, which straddle the boundary between tragedy and farce, are an irresistible gift for tabloid editors. Ostensibly less outrageous stories can also evolve into long-running scandals if, for example, they emerge in a slow news week and there are willing sources for follow-up stories, or even, as in the case of Stephen ‘Liar’ Byers, the minister has a headline-friendly name. The end is nigh when a story remains in the papers long enough to turn heads in the public at large. Former Downing Street director of communications Alastair Campbell reportedly stated as a rule of thumb that anyone who dominates the headlines for two consecutive Sundays should pack their bags. On the evidence of this book, many can survive for longer than that, but, once a beleaguered politician starts fending off unremitting attacks on all fronts, their days are numbered.

In the background of most ministerial resignations there is a canny opposition MP keeping the scandal in the news. Robin Cook carefully cultivated the controversy over opposite number Edwina Currie’s controversial comments about salmonella in 1988, while Labour’s backbench attack dogs Simon Danczuk and John Mann were tireless in pressing the issues that destroyed, respectively, Chris Huhne and Liam Fox. In contrast, a poor performer can allow their besieged opponent to survive. Theresa May repeatedly let Stephen Byers off the hook in 2002 with her dreary parliamentary performances, while in 2017 shadow Home Secretary Diane Abbott failed to take advantage of the news that her opposite number had deported an asylum seeker in flagrant breach of a court order.

Crucially, a minister hoping to fight off a scandal must never appear dishonest. For politicians, this is harder than it sounds. Although outright lies of the kind that terminated John Profumo’s career are rare, ministers commonly tie themselves in knots when attempting to skirt around a difficult topic. This book is littered with examples, from Leon Brittan to Liam Fox, of those figures who may have survived if they had not been evasive when backed into a corner.

Sometimes it is better to quit than to fight, for there is such a thing as a good resignation. To pull off this rare feat, the minister must depart well before the incident has entered the public consciousness. There is no room for Clare Short’s agonising vacillations over whether to depart over Iraq – it is critical to be decisive. To avoid further revelations fanning the flames of a scandal, the full facts must be willingly put out into the open, accompanied by a fulsome expression of support for the government and an understated resignation letter. Under these terms, rehabilitation is possible after a period on the back benches.

There is a noble tradition of tactically speedy resignations. In 1890, the Irish nationalist MP Charles Stewart Parnell lost the support of Parliament after being exposed for having an affair. His friend Cecil Rhodes, then South African Prime Minister, sent him a telegram from Cape Town reading: ‘RESIGN. MARRY. RETURN.’ – solid advice to this day. The most skilful quitter in recent years was Conservative MP Mark Harper, who, in 2013, managed to hire an illegal immigrant as his cleaner while serving as Minister of State for Immigration. He took the plunge and resigned before the story had fully emerged, releasing a concise statement on a Saturday night before melting into the background. After three months, he was back in government with a better job, his misdemeanour forgotten. Within the year, he had been promoted to Chief Whip.

There are irresistible patterns linking the most dramatic downfalls. Resignations prompted by a disagreement over policy have overwhelmingly concerned one subject. The UK’s membership of the European Community has been the most destructive issue to seep into British politics since the Second World War. From the moment Roy Jenkins and two colleagues quit the Labour shadow Cabinet in 1971, in protest against their leader’s support for a referendum on membership of the Community, the European question has cleaved an inexorable fault line through the major political parties. Six of Margaret Thatcher’s Cabinet ministers resigned over Europe, triggering the vicious war that would later cause David Cameron to lose Douglas Carswell and Mark Reckless from the Conservative benches and Iain Duncan Smith from the government, before eventually prompting his own resignation. As this book shows, his successor has fared no better. The Labour Party’s split, so destructive in the 1980s, has now re-emerged with the election to the party leadership of lifelong anti-EU activist Jeremy Corbyn. His lacklustre efforts in 2016’s referendum campaign triggered the departure of over 100 frontbenchers, including fifty in one weekend. As Britain continues to hurtle towards a messy exit from the bloc, there will be more resignations in which Europe plays its part.

Whether they have quit over policy or scandal, there are personality traits that link most of the politicians considered in this book. None were cautious bureaucrats or punctilious administrators; rather they were gamblers and thrill-seekers, inspired to brilliance and vulnerable to catastrophe in equal measure. Few public figures would dare to take a stand in open defiance of the popular position, as Michael Heseltine and Robin Cook did. Similarly, pursuing an unconventional sex life under a nom de plume is not an activity for the faint-hearted politician. One wonders, for instance, how Labour MP Keith Vaz convinced himself that he would stay out of the papers when hiring rent boys while pretending to be a washing machine salesman named Jim. John Profumo, John Stonehouse and Chris Huhne pushed matters yet further: all knew they were likely to be caught out, yet were brazenly dishonest and confidently backed themselves to get away with it. But it should not be any surprise that the most successful MPs have a propensity for recklessness and delusional self-belief. They have, after all, chosen a career that invariably ends in failure.

The decades following the Second World War proved a uniquely fertile breeding ground for scandal. From the late 1950s onwards, social change was in the air, and all authority fell to be questioned. The Profumo Affair in 1963 exposed a world of hidden privilege and vice, prompting a shocked public never again to grant politicians the benefit of the doubt. In response, a new class of ambitious press barons emerged to rival previously entrenched establishment figures like Lords Beaverbrook and Rothermere. These proprietors, from Rupert Murdoch to Robert Maxwell, took their chance to build business empires off the back of the public’s newly found insatiable desire for scandal. Their journalists soon became experts at digging up morsels to feed the unquenchable appetite for intrigue, catching a whole generation of public figures off their guard.

The socially conservative newspaper readers of the 1960s took a prurient interest in what they deemed deviant behaviour. Many of the stories in this book explore the consequences of being a gay politician, with most of its subjects growing up at a time when homosexuality was neither legal nor openly tolerated. Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe’s actions would in any age be deemed worthy of resignation, but they were born out of the extreme lengths to which he went to hide his sexuality from public view. Although the law had shifted to decriminalise abortion and homosexuality by the late 1960s, public attitudes took far longer to change. As late as 1998, there was still no question that Ron Davies’s ministerial career was over when he was apparently caught with a man on Clapham Common in a scandal that caused as progressive a figure as Tony Blair to worry that ‘we could get away with Ron as a one-off aberration, but if the public start to think the whole Cabinet is indulging in gay sex we could have a bit of a political problem’.

With Blair’s government, the pace of change increased sharply, and in a demonstration of how far attitudes had shifted, Thorpe’s successor, Tim Farron, a staunch Christian, was heavily criticised in 2017 after giving the impression he believed gay sex was a sin. His inability to deny this overshadowed his party’s entire general election campaign and eventually contributed to his own resignation. The current liberal sentiment means that the resigning matters of yesterday barely make the news in modern times. Indeed, there is perhaps today a greater respect in the media for the private lives of politicians than before.

But it is not only social change that has rendered the dramatic resignation an endangered species. Knowing how easily careers are ruined by a tenacious press and baying public, those entering politics are far more careful than their predecessors were. In an age when mobile phone cameras and social media make personal information readily accessible, there is now barely any distinction between the public and private life. As it is impossible to keep a secret for long, most prefer to keep no secrets at all, and there are, one suspects, fewer scandals waiting to be uncovered.

Commentators rightly bemoan the present shortage of great political characters. It is the threat of scandal that has nearly eliminated the reckless gambler from public life, and instead replaced them with those who remain vigilant in avoiding any risky situations. Most ministers now plot their route to power from youth, scouring their social media history for potential embarrassments and ensuring that their lives never appear too extravagant. With Britain’s leading figures ever more cautious, and the public less prone to being shocked, the end may be in sight for the age of the great political resignation.

CHAPTER ONE THE DUCHESS OF ATHOLL

Katharine Atholl was a most unusual lady, and a knot of contra dictions. The woman who would become known as the ‘Red Duchess’ was a pioneer of the women’s movement that believed her gender better suited for the home; an anti-Soviet polemicist who fought alongside socialists; and a female minister who always rejected women’s right to vote. It may come as a surprise that she is most distinguished by her stubborn constancy during a protest that ended her political career. On the eve of a world war that she had foreseen before most others, the duchess took the unprecedented step of triggering a by-election that nearly destroyed Neville Chamberlain’s fragile grip on power.

Born into Scotland’s ancient Ramsay family on 6 November 1874, she spent a happy childhood in the artistic circles of Scottish high society. She was a talented pianist and composer, becoming one of an elite group of women to study at the Royal College of Music under Sir Hubert Parry. It was here that she met Ted Butler, the son of one of her tutors, who became the first – and enduring – love of her life. But the middle-class Butler family were not considered suitable company for the aristocratic young lady. In a move that prompted her lifelong resentment, her family ended the relationship, cut short her studies and enforced a return to Scotland. She was instructed to wait for a suitable husband, and was eventually sent off to the palatial Blair Castle to marry John, the heir to the Dukedom of Atholl.

John was a gentle man and a natural homemaker. Against his inclinations, his father pressured him to become a Conservative politician, and he was duly awarded the safe seat of West Perthshire.

The marriage to Katharine reversed customary gender roles. He preferred the confines of the home, where he was an enthusiastic host, while she took to the public sphere, gaining a reputation as a confident and effective operator who harboured little affection for domesticity. While her husband reluctantly came to terms with parliamentary procedure, she ascended to the head of the Perthshire Women’s Unionist Association, edited a military history of Perthshire and became a leading voice in local government in the region.

The marriage was underscored by sadness, however, for the couple were unable to produce a child. Believing that motherhood was ‘the basic fact of [women’s] existence’, Katharine was dogged by a pervading sense of failure. Bereft of the chance to head a family, she decided instead to devote her life to politics.

John held his seat until 1917, when he succeeded his father to become the eighth Duke of Atholl. He resigned his place in the House of Commons to take up his birthright of a seat in the House of Lords. While it was not uncommon at the time for hereditary peers to become MPs before later moving to Parliament’s upper chamber, John’s departure sparked a chain of events that shocked his local party. His successor as local Tory candidate in West Perthshire proceeded to lose the next election to a rival Liberal. Reeling from the surprise result, the West Perthshire Conservative Association did not select a new candidate for four years.

In 1923, the former Liberal Prime Minister David Lloyd George came to Blair Castle on a social visit. It was over dinner that he suggested to Katharine that she should become one of the first women to enter Parliament. Immediately taken with the idea, she determined to stand, ignoring the objections of her husband and also of King George V, who, naturally, was a family friend. She duly wrote to the Conservative Association to nominate herself and was unanimously adopted as their candidate in the election later that year. On defeating her Liberal opponent, she became the first female MP in Scotland. Over the next fifteen years she proved so popular that her majority soared from 150 to over 5,000 votes.

The duchess’s parliamentary career was defined by conviction over ambition. Her maiden speech set out her personal priorities – the welfare of women and children, the protection of the empire and a vociferous opposition to socialism. Plainly dressed and humourless, she was caricatured as a schoolmistress. When the eight women elected in 1923 met with one another, she found the gatherings ‘very friendly, but … rather an ordeal’, noting that their wild divergence of opinion on a range of issues trumped any gender-based solidarity. Unlike her colleagues, she felt that ‘the supreme sphere of women must remain the home’, as ‘we, who are incapable of taking upon ourselves the burden of national defence, should have [no] decisive voice in questions of peace and war’. Perhaps because of her opposition to the further preferment of women, she was appointed by Stanley Baldwin as the first female minister in a Conservative government.

The duchess grew into a belligerent campaigner with a penchant for unpopular causes. Her husband observed that ‘if there was a breeze, she would always face it’. A notably uninspiring speaker, however, she was nicknamed the ‘Begum of Blair’ for her rambling and tortured interventions. Sometimes, her speeches ironically sometimes achieved the opposite of what was intended, with a vigorous defence of the Hoare–Laval Pact reported to have convinced several MPs to oppose it.

Despite her rhetorical shortcomings, the young minister was vindicated on many of the issues that she chose to make her own. The first cause she seized upon with passion was the plight of the people in Soviet Russia. With the assistance of exiled Tsarist leaders, she began to draw attention to the starvation, religious persecution and forced labour faced by millions under Stalin’s rule. She then conducted a forensic study of Soviet society, publishing her findings in a book entitled Conscription of a People. Written at a time when Soviet dupes such as Sidney and Beatrice Webb were extolling Stalin’s virtues, this stands as one of Britain’s first trenchant critiques of Bolshevism.

She was also a leading advocate for the better treatment of women across the world, a cause that gave her an early taste of bipartisanship. In 1931, she led a cross-party delegation to the International Conference on African Children and called on all colonial powers to put an end to female genital mutilation – another issue on which she was well ahead of her time.

But it was the more traditional realms of foreign policy that were to dominate the duchess’s political career. In 1935, Ramsay MacDonald’s government responded to the growing territorial ambitions of Adolf Hitler with appeasement, a policy that was later to prove a grave misjudgement. She became alarmed by the German Chancellor’s audacious remilitarisation of the Rhineland in March 1936. As with the other issues that she had made her own, she first disappeared into the library to undertake thorough research before emerging with a book of her own to release. She began by reading Hitler’s Mein Kampf – not just in the abridged and sanitised English translation, but also in the original German. Shocked by its contents and concerned by how little of Hitler’s malice was conveyed in the English version, she noted that ‘never can a modern statesman have made so startlingly clear to his reader his ambitions’. Reaching the view that it was fascism that was ‘the only serious danger to Europe’, rather than socialism, as the pervading orthodoxy would have it, she released her own translation of Hitler’s tome in May 1936. This publication began to convince her allies and constituents of the imminent danger posed by the German dictator.

The duchess’s burgeoning reputation as a maverick was reinforced by the stance she took over the Spanish Civil War; a war triggered by the attempt of the ultra-conservative General Franco to overthrow the democratically elected socialist government. Franco was backed by Mussolini, Hitler and by British and American companies that feared the spread of socialism. Soviet Russia supported the governing Republicans. The ensuing conflict became a uniting cause for the British left, portrayed as a fight for socialism against the forces of capitalism and fascism. Although Britain’s government remained neutral, thousands of leftists volunteered to fight for the Republicans in the International Brigades.

The duchess declared herself a strong supporter of the Republican cause. Isolated among her Tory colleagues, who overwhelmingly backed Franco, she became close to those socialists that she had formerly despised. In 1938, she visited Spain with three female colleagues from the Labour Party to arrange the evacuation of 4,000 Basque children to London, an act that several Tory colleagues regarded as treason. She was in Madrid when it was bombed by Franco’s forces and returned traumatised by what she had seen. Again, she retreated to the library before presenting her research and empirical testimony in a book: Searchlight on Spain sold over 300,000 copies in Britain and was soon translated into French, Spanish and German. It set out a detailed history of the events leading up to the war, outlined the humanitarian crisis and called for the British government to arm the Republicans against their fascist opponents.

Exasperating her anti-Soviet party colleagues further, the duchess began to associate with outwardly leftist Republican supporters, even addressing meetings of the International Peace Campaign at which the left-wing anthem ‘The Red Flag’, today the Labour Party’s unofficial song, was bellowed out. It was these curious appearances that earned her the nickname ‘Red Duchess’.

Her position on Spain brought her into bitter conflict with her own constituents. The significant contingent of West Perthshire Roman Catholics fiercely supported Franco, and many on the anti-Soviet right considered the rise of fascism a welcome bulwark against communism. Most importantly, middle-class electors were offended by her neglect of local issues and flagrant disloyalty to her party. She had come to rely on the continuing support of her voters and Conservative Association members without canvassing their views. In a stark warning, they declared that they had been tolerant ‘almost to breaking point’. Affronted by such insolence, she declared herself ‘not the delegate of the Association with a commission to act on its behalf’, but ‘the representative in Parliament of the constituency’.

On the morning of 12 March 1938, the Nazis left the Treaty of Versailles in tatters by invading Austria, establishing the Anschluss that formed the starting point for Hitler’s vision of a Third Reich. This aggression took Europe a step closer to war, and further emboldened the duchess. On 22 April, she publicly criticised Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain for his naïveté and declared that Hitler must be defeated. Disregarding the growing insurrection in her constituency, she embarked on a lecture tour of the USA in a forlorn attempt to direct American attention towards the European crisis.

While she was across the Atlantic, Chamberlain signed the Munich Agreement in which he accepted Hitler’s promise that Germany would not provoke a war with Britain. The duchess was implored by her embarrassed husband, her friends and parliamentary colleagues not to criticise the accord upon which Chamberlain had staked his premiership. She refused, and within weeks was distributing pamphlets castigating the agreement as a shameful surrender.

Her actions were the final straw for her constituency association members, who voted to deselect her as their parliamentary candidate. The duchess’s response was characteristically bold. Ignoring the advice of her friend and fellow anti-appeasement campaigner Winston Churchill, she decided to resign as an MP, to trigger a by-election and stand on the single-issue platform of opposing the policy of appeasement. On 24 November 1938, she was appointed the Crown Steward of the Chiltern Hundreds, a ceremonial title awarded to resigning members of Parliament, and officially triggered the ballot, which was held less than a month later. Her slogan was pithy and to the point: ‘Country before Party’.

In a move that demonstrated the growing level of consensus outside the Conservative Party about her views, the Liberals decided not to field a candidate against her. This left the by-election a straight fight between the duchess and her former party. The short campaign suited her, as growing scepticism about the Munich Agreement coincided with rumours of Nazi abuse of Jews in Germany.

Her Conservative opponent, William McNair Snadden, embarked on a tour of all areas of the constituency, speaking at sixty-four public meetings in three weeks and receiving strong backing from a Conservative Association united against their former MP. Chamberlain, aware that a loss would catastrophically undermine his flagship policy, despatched fifty Conservative MPs to West Perthshire. These included his own parliamentary private secretary and the Secretary of State for Scotland. All the Tories repeated the same message – a vote for them was a vote to avoid war. In contrast, a vote for the Red Duchess risked the lives of your children. This warning resonated strongly with a generation scarred by the Great War.

By all accounts the duchess ran a poor by-election campaign. She neglected the more populous towns in favour of Conservative-voting villages. Public meetings were badly advertised and ill-attended. Accepting that the gentry and middle class would stick with Chamberlain, she sensibly targeted the working class, but adopted a patronising tone that failed to win over her targets. She also continued to antagonise her former Catholic voters by speaking at length about Spain. They could not tolerate her criticism of General Franco, who sought to restore the privileged status of the church that had been eroded by the Republicans.

The few Tory colleagues who shared her views failed to come to her assistance, fearing retribution from their own constituency associations. The enigmatic Bob Boothby had promised to campaign at her side, but withdrew because his local chairman threatened to resign. He sent her a short letter admitting: ‘Frankly, I cannot face this.’ The only Tory to offer open support was Churchill, who wrote publicly to say:

The fact remains that outside our island, your defeat at this moment would be relished by the enemies of Britain and of freedom in every part of the world. It would be widely accepted as another sign that Great Britain … no longer has the spirit and willpower to confront the tyrannies and cruel persecutions which have darkened this age.

But that letter was as far as Churchill was prepared to go. The Tory whips had told him that he would be expelled if he joined her campaign and he recognised the importance of remaining in a prominent position if, as he anticipated, war broke out across Europe.

The duchess did receive some endorsements, but not all were welcome. Radical Labour MPs and communist activists descended upon West Perthshire to campaign for her, significantly boosting her rival’s cause. The support of suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst, who declared ‘every woman who prizes her vote should vote for [Kitty]’, failed to win the approval of the patrician electors of Kinross. Most disastrously of all, with only two days to go, the newspapers received a mocking telegram from Joseph Stalin himself, reading: ‘Moscow is proud of Katharine the even greater.’

Although she remained dignified throughout the campaign, she was shocked at the viciousness of her former party. It was the dirtiest by-election that had ever been contested. Tory employers secured votes by increasing their workers’ wages, while estate owners suspended tenants’ rent in return for support and local businesses were ordered to take down her posters.

Despite the tactics deployed against her, the duchess expected to secure sufficient Liberal votes to win. It was not to be. Snadden triumphed with a majority of over 1,000 votes following a blizzard on the day of voting. The Conservatives had, unlike Kitty, arranged buses to take voters through the snow to the polls. Snadden’s team were not gracious in victory, with one laird sending the duchess a telegram reading: ‘Am delighted you are out. Hope my Rannoch people voted against you. Now you might find time to remove your Basque children from Suffolk.’

She was mortified by the result, writing in her autobiography that ‘[the loss] was a blow, and I hated to think how I had let down all those who had helped me’. She realised that she had ‘forgotten the extent to which the myth of Mr Chamberlain as the saviour of peace still gripped the country’. After her defeat, she briefly considered a return as an MP. But, as she predicted, Hitler proceeded to ignore the Munich Agreement, invaded Poland and triggered the start of the Second World War. Devoting herself to the war effort, she served as the Secretary of the Scottish Invasion Committee, tasked with the responsibility of preparing for a German attack. After the war, she became founding chair of the British League for European Freedom and campaigned against the Soviets’ influence in Eastern Europe.

The duchess never regretted her resignation, which stands alone as an example of a lone MP triggering a pivotal national debate on a single issue. A similar feat was attempted by David Davis in 2008, when he resigned as an MP to force a by-election about the erosion of civil liberties. Although his cause had widespread public support and he had more immediate access to journalists, he did not manage to generate significant attention. Davis’s failure highlights the Duchess of Atholl’s achievement. Had the by-election gone the other way, she might just have altered the course of the Second World War.

CHAPTER TWO JOHN PROFUMO

This was the scandal that had it all. Glamorous aristocrats, gorgeous call girls, East End gangsters, Russian spies and a rank miscarriage of justice. Above all else, the resignation of the Secretary of State for War permanently broke apart British society’s fusty and buttoned-up façade. For the first time, the public realised that behind their haughty exterior, members of the establishment were at it like rabbits.

Scion of a dynasty of Sardinian barons that had become enmeshed in English high society, the young John Profumo was educated at Harrow and Oxford before joining the army shortly before the start of the Second World War. Having triumphantly led his men into Normandy on D-Day, he emerged from the conflict a highly decorated brigadier. He returned to the House of Commons in 1950, having already served a stint as an MP between 1940 and 1945. Intelligent, smooth and charming, Profumo moved in bohemian circles and always had an eye for the ladies. He frequently toured Soho’s topless nightclubs and remained single until the age of thirty-nine. Soon after his marriage to famous actress Valerie Hobson, he was promoted by then Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, and took his seat on the government front bench.

On a hot July weekend in 1961, the year after his elevation, Profumo and his wife made the short journey to Cliveden, Lord Astor’s magnificent Buckinghamshire estate. They had been invited to spend a long weekend with Astor and other distinguished guests. On the Saturday evening, while enjoying a stroll around the grounds with his host, Profumo spied a leggy brunette standing stark naked by the swimming pool. The minister was instantly smitten with the beautiful young girl, and he and Astor chased her all around the pool, hiding her towel.

She was Christine Keeler, a nineteen-year-old model and friend of high-society osteopath Stephen Ward, the tenant of a small cottage on Astor’s estate. Keeler has often been cast as a shameless temptress, but in truth she was a troubled and vulnerable teenager. Sexually abused by her stepfather in her youth, she had fled to London two years earlier after aborting her baby with a knitting needle. On reaching the big city, she became a topless dancer in a Soho nightclub where she met the 47-year-old Ward. Her distinctive beauty and easy charm made her the ideal girl for him to introduce to his influential clients.

That evening, Keeler and Ward sat down for dinner with Astor and his guests, who included the President of Pakistan and the Queen’s cousin Lord Mountbatten. Profumo ended the night chasing Keeler through the upstairs bedrooms and, out of sight of his wife, gave her a surreptitious grope behind a suit of armour.

Ward, who had been asked by Astor to bring girls that would get on with his guests, observed the flirtation with considerable satisfaction. At the time, he was London’s go-to osteopath, boasting a client list that included Winston Churchill, Frank Sinatra and Elizabeth Taylor. His professional success brought with it considerable social standing, enabling him to moonlight as a portrait painter to the stars. Ward’s renowned parties were known for their diverse list of attendees, but always included a throng of beautiful young girls. Despite being, by his own admission, ‘not handsome’ and with ‘no money’, he considered himself ‘one of the most successful men in town with girls’. One of his former girlfriends recalled that he took ‘immense excitement and satisfaction’ in organising orgies. He enjoyed ‘watching someone else making love to a girl of whom he was fond. And the more passionate or violent the sex act, the more it seemed to satisfy him.’

One of Ward’s favourite clients was Soviet naval attaché and spy Eugene Ivanov. The pair had first met over lunch at the Garrick Club, introduced by the editor of the Daily Telegraph, and they had struck up a close friendship. Ivanov, who had already been noted by MI5 for possessing a ‘thirst for women’, became a frequent attendee at Ward’s parties. The Russian arrived at the Cliveden cottage the morning after Profumo met Keeler. As soon as he had unpacked his bags, the group converged by the pool. Ward later recalled that ‘Ivanov and [Profumo] had a race down the pool …We started off with a countdown, “Three, two, one, fire” in Ivanov’s honour. And although no legs were to be used, John Profumo shot ahead – using his legs.’ Having cheated to win the race, Profumo joked that his actions should teach Ivanov a lesson about trusting the British government.

Keeler was instantly attracted to the glamorous Russian, and at the end of the day asked him to drive her home. Once they had arrived at the mews house she shared with Ward, she invited him up for a cup of coffee. He produced from his jacket a bottle of vodka and poured them both a large glass. According to Keeler, before long they were having ‘good old-fashioned sex without any fuss or trimmings’ on the kitchen floor.

With no idea that Keeler was involved with the Russian agent, Profumo resumed his pursuit of her after the weekend. After obtaining her telephone number from Ward, he arranged to meet up with her and soon the pair was having what Keeler described as frequent ‘screws of convenience’. These occurred in a variety of locations, from Ward’s flat to Profumo’s Mini Cooper, his friend’s Bentley and, once, his marital bed. The Secretary of State spoiled his new lover, buying her gifts and giving her money ostensibly ‘for her mother’. Ward actively encouraged her to continue the affair, joking that he was able to start a world war.

Keeler always knew that her dalliance with Profumo ‘was no grand romance’, and that she was ‘clearly not the first girl he chased’. For Keeler, their sex ‘had no more meaning than a handshake or a look across a crowded room’. She was far more excited by the ursine Ivanov, whom she continued to see, apparently ignorant of the threat to national security that this presented.

The security services were not as oblivious. Aware that Ward was, in the words of one agent, ‘the provider of popsies for rich people’, they spied the chance to honeytrap the Soviet. After putting Keeler under surveillance, they rapidly discovered that she was also sleeping with Profumo. This realisation prompted the panicked head of MI5 to contact the Cabinet Secretary, who subtly warned the Secretary of State for War to be careful about his private life.

Profumo took the hint and soon after wrote a polite note to Keeler breaking off their month-long fling. She was not particularly disappointed and soon turned her gaze to two East End hustlers: Johnny Edgecombe and ‘Lucky’ Gordon. Her two-timing eventually ended with a fight at a Soho jazz club, which left Gordon with a badly slashed face. Keeler briefly moved in to Edgecombe’s house in Essex but soon grew tired of him and returned to Ward.

In December 1962, the spurned Edgecombe arrived at Ward’s house and attempted to shoulder the door down. When Keeler refused to let him in, he drew a handgun and fired six shots at the door before being arrested for attempted murder. Shaken by the attack and fearing that his high-society friends would abandon him if he courted publicity, Ward ordered Keeler to leave.

Seething at Ward’s brutality, she sought to destroy his social standing and make herself some serious money in the process. She approached journalist Paul Mann and Labour MP John Lewis and recounted the story of her trysts with Profumo and Ivanov. Lewis tape-recorded her allegations while Mann persuaded her to go to the press. After she showed a Sunday Pictorial reporter a note written to her by Profumo, they offered her £1,000 for the exclusive: the largest sum that had ever been paid for a news story.

The Prime Minister was told in February 1963 that Profumo had been having an affair, but, having not been briefed about the Ivanov connection, failed to recognise the security risk it posed. To Macmillan, it seemed to be simply part of the routine escapades of Profumo’s louche set and none of his business. He noted in his diary that his minister

had behaved foolishly and indiscreetly, but not wickedly. His wife is very nice and sensible. Of course, all these people move in a selfish, theatrical, bohemian society, where no one really knows anyone and everyone is ‘darling’. But Profumo does not seem to have realised that we have, in public life – to observe different standards from those prevalent today in many circles.

Johnny Edgecombe was due to stand trial in March 1963 for his attack on Ward’s flat. Despite appearing as a witness in the preliminary hearings, Keeler absconded before the main trial, decamping with a journalist to a remote fishing village in Spain to prepare for the release of her story by the Sunday Pictorial.

Realising that his business and social lives were about to be ruined, Ward panicked. He tipped off Profumo and begged the minister to help him bury the story. Forming an unlikely team, the pair contacted Keeler, who offered to deny everything if she was paid £5,000. Neither man was prepared to submit to this extortion, knowing that she would come back for more money eventually.

Profumo instead deployed his extensive contact book to try to stop the story coming out. His first move was to persuade MI5 to impose reporting restrictions on Keeler. When that failed, he and Ward heaped pressure upon Reg Payne, the editor of the Sunday Pictorial. Out of deference to Profumo, and realising that he would be relying on the word of a young girl on the run from the law against a Cabinet minister of unblemished reputation, Payne agreed to drop the story. For a short time, it looked like Ward and Profumo had escaped.

Fleet Street’s hacks have never been, however, renowned for their discretion. Within weeks, reporters across the world had heard rumours of Profumo’s extramarital activities. The editor of the Daily Express decided to hint heavily at the scandal, publishing the headline ‘War Minister Shock’ and asserting on his front page that Profumo had offered his resignation to Harold Macmillan for mysterious reasons. Placed right next to the story on the front page was an ostensibly separate article about Christine Keeler’s disappearance, and the inside pages were adorned with the now-infamous pictures of Keeler wrapping her legs around an Arne Jacobsen chair. Realising that the scandal was bound to unfold, Commander Ivanov quietly left Britain, never to return.

The Labour Party needed no excuse to spread the juicy rumours about Profumo further, but the security implications provided a good reason to keep the story going. ‘Westminster Confidential’, the House of Commons’s internal newsletter, printed the outline of the allegations in their March edition, asking: ‘Who was using the call girl to milk whom of information – the War Secretary or the Soviet military attaché?’

Profumo moved into damage-limitation mode. He called his most senior colleagues to deny his having an affair with Keeler, imploring them to believe that the allegations had been invented. For many Tory ministers, suspicion soon melted into sympathy. Their attitude must be understood in the context of the previous year’s Vassall Affair, in which a young British diplomat was honeytrapped by the Soviets and forced to turn spy against his own country. As that scandal emerged, damaging rumours were spread about Conservative minister Thomas Galbraith’s close relationship with the traitor. Galbraith was forced to resign, but was cleared of any impropriety in a subsequent inquiry. Since then, many MPs had taken a dim view of journalists’ reliability and were prepared to give Profumo the benefit of the doubt.

Fearful of libel actions, the tabloid editors would go no further than the Daily Express’s insinuation. It was left to politicians to expose the affair using parliamentary privilege, an ancient right permitting MPs to speak with impunity when in the House. One Labour MP was only too happy to oblige. Colonel George Wigg harboured a long-standing grudge against Profumo, having clashed with him over military provision when he complained that the Secretary of State for War was willing to send troops into battle ‘without anti-aircraft cover, with ineffective anti-tank weapons, with no ground strike force, short of long-range fighters and without any satisfactory long-distance freighters’. The colonel quipped: ‘If that satisfies him then God help us if he had been disappointed.’ On that occasion, Profumo loftily batted away Wigg’s grievance and failed to contact him afterwards. It was to prove a fatal error.

On 21 March 1963, Wigg used an obscure parliamentary debate held at 10 p.m. to relay the rumours to the House of Commons, saying:

There is not an honourable member of this House, nor a journalist in the press gallery, nor do I believe there is a person in the public gallery, who in the last few days has not heard rumour upon rumour involving a member of the government front bench. The press has got as near as it can – it has shown itself willing to wound, but afraid to strike … In actual fact, these great press lords, these men who control great instruments of public opinion and power, do not have the guts to discharge the duty they are now claiming for themselves. That being the case, I rightly use the privilege of the House of Commons – that is what it is given to me for – to ask the Home Secretary, who is the senior member of the government on the Treasury bench now, to go to the despatch box – he knows the rumour to which I refer relates to Miss Christine Keeler … and a shooting by a West Indian – and, on behalf of the government, categorically deny the truth of these rumours. On the other hand, if there is anything in them, I urge him to ask the Prime Minister to do what was not done in the Vassall case – set up a select committee so that these things can be dissipated, and the honour of the minister concerned freed from the implications and innuendoes that are being spread at the present time.

Wigg’s call for an inquiry was supported by prominent Labour frontbenchers Richard Crossman and Barbara Castle, who asked the Home Secretary if Profumo had been sleeping with Keeler. Rising to defend Profumo, the Home Secretary was dismissive, saying: ‘I do not propose to comment on rumours which have been raised under the cloak of privilege and safe from any action at law. [The Labour Party] should seek other means of making these insinuations if they are prepared to substantiate them.’