13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

When Hitler ordered the north of Nazi-occupied Norway to be destroyed in a scorched earth retreat in 1944, everything of potential use to the Soviet enemy was destroyed. Harbours, bridges and towns were dynamited and every building torched. Fifty thousand people were forcibly evacuated – thousands more fled to hide in caves in sub-zero temperatures. High above the Arctic Circle, the author crosses the region gathering scorched earth stories: of refugees starving on remote islands, fathers shot dead just days before the war ended, grandparents driven mad by relentless bombing, towns burned to the ground. He explores what remains of the Lyngen Line mountain bunkers in the Norwegian Alps, where the Allies feared a last stand by fanatical Nazis – and where starved Soviet prisoners of war too weak to work were dumped in death camps, some driven to cannibalism. With extracts from the Nuremberg trials of the generals who devastated northern Norway and modern reflections on the mental scars that have passed down generations, this is a journey into the heart of a brutal conflict set in a landscape of intense natural beauty.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The writing of this book has depended on much generosity and kindness from many people. Wideroe Airlines flew me across Finnmark and Troms to see for myself the locations of the incidents included here and to meet the people who talk about them so vividly. The hotel groups Rica and Radisson Blu helped too and Hilde Chapman at the Norwegian Embassy in London was a key figure in making this project a reality.

I am grateful to Mette and Øyvind Mikalsen for talking to me about the tragedy of Hopseidet. My special thanks go to Alf Helge Jensen of the Finnmarken newspaper for translating and Oddvar Jensen, owner of Mehamn’s Arctic Hotel, for lending me his Mitsubishi Galant. Gunnar Jaklin was a treasure trove of stories and an encyclopedia of facts in Tromsø while artist Grethe Gunning told me tragic but wonderful stories in Djupvik and introduced me to Roald Berg, who gave me a carved wooden Sami drinking cup as a reminder of my trip. The evergreen Pål Fredriksen guided me around Nordreisa and climbed the Fals mountain to show me the Lyngen Line; Storfjord Mayor Sigmund Steinnes opened his secret files for me.

Film director Knut Erik Jensen was a mine of information in Honningsvåg, as was Rune Rautio in Kirkenes. Karin Johnsen made several important calls for me and told stories I could barely believe – then and now. Author Roger Albrigtsen of the FKLF cleared up many of my queries and offered advice on events in Porsangerfjord: Lieutenant Commander Wiggo Korsvik of the Norwegian Explosive Clearance Commando shared details of ammunition finds.

I am deeply indebted to Michael Stokke of the Narvik Peace Centre for his expertise on prisoners of war and his generosity and patience. I am extremely grateful to Torstein Johnsrud at Gamvik Museum, Yaroslav Bogomilov and Nina Planting Mølman at the Museum of Reconstruction in Hammerfest (Gjenreisningsmuseet for Finnmark og Nord-Troms) and Camilla Carlsen, Bodil Knudsen Dago and Berit Nilsen at the Grenselandsmuseet in Kirkenes.

Thanks to historian Kristian Husvik Skancke for his time, knowledge and guidance, and to Professor Frederik Fagertun at Tromsø University who was kind enough to advise on aspects of the project.

Special mention must be made of Mrs Bjarnhild Tulloch, a survivor of the scorched-earth policy in Kirkenes and whose childhood memoir Terror in the Arctic – one of the few accounts of the time in English – was a significant research guide. For her kindness in recommending me to her friends Svea Andersen, Eva Larsen and Knut Tharaldsen, as well as Inga and Idar Russveld, I cannot thank her enough.

Curt Hanson, Head of the Elwyn B. Robinson Department of Special Collections at the University of North Dakota gave me permission to use the Nuremberg trial transcripts from his archive. Øyvind Waldeland kindly released pictures from the archive of Oslo’s Defence Museum.

My friends Ian Muir, David Ford and Simon Price offered encouragement throughout, as did Shaun Barrington of The History Press. My thanks also go to Chris Shaw, who did the copyediting.

Finally, special thanks go to my wonderful wife Daiga Kamerade and my son Martins Vitolins. Their patience and humour helped keep me sane and sustained me in the many hours of research and writing required.

Vincent Hunt

Manchester, England

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

List of illustrations

Introduction

Map of Northern Norway

1

‘It was absolutely normal growing up playing with ammunition’

2

‘Pity for the civilian population is out of place’

3

‘The destruction was as complete as it could be’

4

The villagers that escaped and the town full of Nazis

5

Still mourning the men of Hopseidet

6

The white church of Honningsvåg

7

The destruction of Hammerfest

8

Refugees, rescues and resistance

9

The death of Erika Schöne and other secret tragedies

10

‘You must not think we destroyed wantonly or senselessly’

11

‘Oh, I know of a land far up north …’

12

Even in the wilderness, there was war

13

Into the valley of the damned: the Mallnitz death camp

14

Walking in the footsteps of the doomed: the Lyngen Line

15

A guided tour through Tromsø’s war

16

Scorched earth stories at first hand

17

Slaughter and supply from the sky

18

Questions mount on the streets of the capital

19

Dark chapters and Cold Wars

20

The war is not over

Appendix 1 The cost of the scorched earth policy

Appendix 2 Worst crashes in Norwegian aviation history

Appendix 3 Arbeiderpartiet response

Plates

Copyright

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Map 1: Norway north of the Arctic Circle – Finnmark and Nord-Troms

2. Kirkenes after the German withdrawal

3. The destruction of Kirkenes

4. German supplies in Kirkenes

5. Eva Larsen and Knut Tharaldsen

6. A rare pre-war building in Kirkenes

7. House built on anti-aircraft gun bunker in Kirkenes

8. Finnkonckeila, burned by the Germans during the war

9. Torstein Johnsrud, curator of Gamvik museum

10. Memorial stone at Hopseidet

11. Mette and Øyvind Mikalsen with the author

12. Makeshift hut near Gamvik

13. Nazi officers inspect coastal gun battery site

14. SS troops in Skoganvarre

15. German soldiers bury at comrade in Lakselv

16. The white church in Honningsvåg

17. The burning of Hammerfest

18. The total destruction of Hammerfest

19. A German barracks band in Lakselv

20. Gun bunker at Djupvik

21. Artist Grethe Gunning with Roald Berg

22. The Lyngen mountains

23. Pål Fredriksen at the Lyngen Line

24. A reconstructed German bunker at the Lyngen Line

25. Gunnar Jaklin at the Tromsø Defence Museum

26. The road to the Mallnitz death camp near Skibotn

27. Soviet POWs in May 1945

28. Emaciated Soviet POW, 1945

29. Vidkun Quisling, leader of Norway’s Nazi puppet regime

30. The scorched-earth burning of Finnmark, 1944

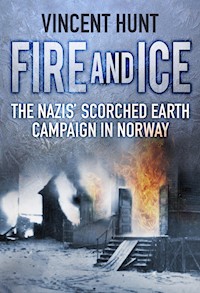

FRONT: Composite of Hammerfest in flames and German soldiers attacking through a burning Norwegian village during the 1940 invasion. Picture by Erich Borchert, provided by the German Federal Archive.

BACK: The church in Honningsvåg was the only building to survive the scorched-earth burning of Finnmark following the German retreat in October 1944. Picture used with permission of the Nordkappmuseet in Honningsvag.

INTRODUCTION

This book is a collection of stories about the destruction and evacuation of northern Norway during the Nazi scorched-earth retreat of October 1944 to May 1945. Its focus is the counties of Finnmark and Troms lying to the far north of the Arctic Circle. Finnmark, west of the Tana River, was reduced to ashes in the retreat and emptied of civilians. The Nazi troops – Austrians, mostly – fell back to a fortified defensive line in the mountains near the Lyngen fjord where they planned a stand against an Allied invasion that never came.

This is a book of social memory: of towns bombed and burned flat with violent death and secret tragedies round every corner; of unspeakable cruelty, misery and brutality, with skinny malnourished children and hollow-eyed prisoners at every turn. The author crossed the region meeting ordinary Norwegians who describe extraordinary experiences or tell how their families and friends fared in a time of great disruption and dislocation. All these stories have been gathered by the author in English but they are Norwegian stories - of death, destruction and trauma in a beautiful land of rugged coastlines, jagged mountains and sub-zero temperatures.

Seventy years on, that land is still stained from its encounter with evil. There are Nazi bullets still in the ground and rusty barbed wire still around trees. Pensioners still have nightmares, and reinforced concrete gun bunkers are still standing, too well built to crumble. They seem as if they will never crumble but will always be there, gazing silently out to sea.

Even today, the war is never very far away in Finnmark. It’s been bottled up in people’s heads for seventy years and the fears have been passed down through two generations since. That third generation can walk into a forest today and still find traces of the war.

One elderly lady in the shattered, battered northern town of Kirkenes said to me: ‘We used to say “Will we never be rid of this war?”’

The answer is no, not yet. The war is still here.

MAP OF NORTHERN NORWAY

1

‘IT WAS ABSOLUTELY NORMAL GROWING UP PLAYING WITH AMMUNITION’

Two women and a man, all three of them elderly, are sitting on a red sofa opposite me in my hotel room in Kirkenes, Norway’s most north-easterly town. We are 400km above the Arctic Circle at the final stop of Norway’s famous Hurtigruten coastal steamers. The border with what was the Soviet Union is 7km east on the other side of the Pasvik river at a controlled crossing called Storskog.

The man, Knut Tharaldsen, worked for many years at the crossing as a border policeman. He grew up on a farm nearby close to a fjord called Jarfjord. As Red Army soldiers pushed the Germans out of the Soviet Union and back into Norway in October 1944, triggering the scorched-earth retreat, his farm was in the centre of the battlefield. Knut, then aged 8, looked on from a forest as the battle raged. As he is about to tell me, he saw things that no child should see.

One of the ladies, Eva Larsen, grew up in a place about 10km from here called Bjørnevatn, the site of an enormous iron ore mine. During the war 3,000 people from Kirkenes sheltered in the mine to escape the incessant bombing of the town and the fighting that liberated them. When Red Army soldiers reached the mine they were greeted with jubilation.

The third member of the group, Svea Andersen, grew up less than 1km from this hotel, down by the harbour. The Germans built a causeway across to an island in the fjord called Prestøia, which they turned into a military stronghold bristling with guns called ‘Festung Kirkenes’(Fortress Kirkenes). Svea’s was the last house before the checkpoint leading to the causeway. It’s still there.

My three guests are about to tell me my first scorched-earth stories. I have a microphone and a tape recorder ready. They are the friends of a lady called Bjarnhild Tulloch, who grew up here and wrote about her wartime experiences in English. Her book – Terror in the Arctic – is one of the few accounts of the war in Kirkenes. Thanks to her generosity in putting me in touch with Svea, Knut and Eva, I have the chance to hear stories about a war I am not familiar with and which will touch me deeply.

Norway will never seem the same again. It is more than a land of picturesque fjords, tourists on Midnight Sun cruises and cheerful cyclists waving from the pages of holiday brochures. There are dark, disturbing chapters buried under the surface. I am at the start of a journey through a landscape of sadness, cruelty and bitterness.

Following the Nazi invasion and occupation of Norway in 1940, Kirkenes became increasingly important to Hitler’s long-term aims. As the military build-up began in preparation for Operation Barbarossa, the strike against the Soviet Union set for the following June, Kirkenes became a vital strategic town. Tens of thousands of troops, mostly specialist Austrian mountain soldiers, or Gebirgsjäger, who were trained for the extreme conditions, were sent to Kirkenes for the northern punch through the Arctic against Murmansk and Leningrad.

Kirkenes was the ideal place: it was an ice-free port very close to the Soviet border with a direct road to Murmansk. German ships and commandeered Norwegian boats brought in tanks, lorries, fuel, weapons, building materials, food and liquor. Warehouses, stores and repair shops were built in the gaps between civilian homes and enough ammunition was brought into Kirkenes to support 100,000 men taking part in the offensive for a year. Soon the town was filled with vehicles, guns, barracks and stables and tens of thousands of men, horses and mules.

The German general in command of the strike was General Eduard Dietl. He had led German troops to victory in an intense two-month battle for Narvik twelve months previously against a combined force of Norwegian, French, British and Polish troops in difficult conditions in the mountains around Narvik, narrowly avoiding defeat when Norway suddenly capitulated in June 1940. On 22 June 1941 Dietl moved his Alpine troops across the Norwegian border to take control of Petsamo, home to a mine producing nickel, a vital component in the manufacture of armour plating. Supported by their Finnish allies, the German operation clicked into a second phase, Operation Platinum Fox, with the aim of pushing on and taking Murmansk. But before long, Dietl’s men met fierce resistance.1 The Russians landed reinforcements east of Petsamo, well before Murmansk, which slowed and then stopped the German advance across the tundra before the advance units could cross the Litsa river.2

Try as he might throughout July, August and September, Dietl could not get across the Litsa, despite repeated and often costly attacks. Soviet reinforcements were poured into the area to protect Murmansk and by late September, with supplies into Kirkenes now threatened by Russian submarines, Hitler was resigned to suspending the offensive for the winter. The Germans called off the attack in September and dug in, having already lost around 10,000 men. They had advanced just 25kms into Soviet territory.3

The lines were drawn for an Arctic war of attrition supplied from Kirkenes that would last for the next three years and claim tens of thousands of lives, not just through combat but also through exposure, frostbite and blizzards. The Litsa Front remained stable until 1944, but the entire situation in the Arctic north changed when the Soviets broke the year-long siege of Leningrad early that year. In the face of powerful Red Army offensives throughout the spring and summer of 1944, the Finns were pushed back from almost all of the territorial gains they had made since 1941 and suffered upwards of 60,000 casualties – military and physical losses that meant Soviet victory was inevitable. Finland’s survival as an independent nation began to hang in the balance and they discreetly opened peace talks with the Soviets.4

To be ready for the increasingly likely event of a Finnish surrender, which would leave them exposed and vulnerable throughout the region, German commanders drew up contingency plans – Operations Birke and Nordlicht (‘Birch’ and ‘Northern Lights’) – to pull their 230,000 men and a mountain of supplies and weapons back to new defensive lines in the mountains surrounding the Lyngenfjord near Tromsø. Here they would regroup to stop any further Soviet advance or Allied invasion.

In late August the Soviets offered Finland a conditional peace deal. The war would end, but the Finns had to pay huge reparations, cede territory and get the Germans out within a fortnight, or turn their guns on their former friends. The Finns accepted the peace deal on 2 September and broke off relations with Germany. The armistice was signed on 19 September.5

General Dietl had died in a plane crash in June 1944 in the Austrian Alps on his way back from a meeting with Hitler to discuss tactics. His replacement was Generaloberst Lothar Rendulic, another Austrian and a veteran of the partisan war in Yugoslavia. As he took command the Soviets were building up their forces for the onslaught of the October 1944 Petsamo–Kirkenes offensive, which would turn the tide of the war on the Northern Front in the Arctic and trigger the German destruction of Finnmark in a scorched-earth retreat back to the Lyngen Line. This is where my scorched-earth stories begin.

Seated in the centre of the hotel room sofa, Eva Larsen, a former teacher in Kirkenes, speaks very good English. She has agreed to tell not only her story but also to translate Knut’s for me. ‘For many years people didn’t want to speak about what they saw in the war. It was not for discussion,’ she says. ‘Knut’s parents after the war didn’t want to speak about what they saw. In October 1944 Knut was 8, so he had lots of memories – very clear and distinct.’

Knut nods. He understands English but doesn’t speak it so well, so Eva translates:

We lived on a farm near Storskog, where you cross the border with Russia. The German general Dietl determined to stop the Russians at a defensive line near to my home. He went back to Germany and discussed with Hitler how to do it. They built a series of short trenches in the hills from where the Germans could fire on the Soviets. We can see them today when we are picking blueberries.

Hitler told Dietl to get 5,000 soldiers to stop the Soviets but as it was the end of the war it was difficult to get that many. So he had to use youngsters, especially young boys from Austria, who were trained in mountain war.

The Germans had to retreat from the Litsa Front back to Norway on 17 October 1944. There was fierce fighting between the Russians and the Germans. On 22 October there was no more left of the German army. They were destroyed. There were German soldiers lying by the side of the road with their intestines outside their body, crying for their mothers. And later, Russians.

The fighting happened very close to my home. The Germans had taken over our house and one of their officers was wounded and died. It was winter – they couldn’t bury him. So they threw him outside the house. He was lying there for a whole winter. If a German soldier was so badly wounded they couldn’t save him, special German soldiers were commanded to kill their own. They would shoot him, put him out of his misery with a mercy shot.

It was not a big house, but thirty-eight people were living in it, on the floor and in every bedroom and in the hall and everything. There were two Germans living in the kitchen. When the house was modernised after the war you could still see the blood spots on the floorboards and in the kitchen from the wounded officers.

The fighting was coming from the air, from bombing, man-to-man fighting as the Russians attacked the Germans. The war was so close our house was used by both sides. At three o’clock in the morning the Germans left: by four thirty Soviet officers were in the kitchen.

There was fighting for many days. I saw it all. We were hiding in the forest in a shelter my father made, but we were close to the house. Fewer and fewer Germans were coming and more and more Russians. I saw a German soldier lying in the field next to the house shooting at the Russians but he had no helmet. He was hit many times and the front of his head was blown off. I was 10 metres away.

The Russians used to say: ‘Bayonet the Germans in the back, above the belt, above his ammunition belt.’ When they ran after the retreating Germans they would bayonet them in the back as the blade wouldn’t stick. It was easier to kill them. The boys were lying by the side of the road, fatally injured, waiting to die, crying for their mothers.

Of course what you saw as a child affected people very badly: it made many children alcoholics after the war. It’s a miracle I am not insane because of all I have seen as a young boy.

Svea and Eva were nodding solemnly and grimacing as Knut told his stories. Now they speak up. ‘I think it was special that in Kirkenes we lived in a sort of friendship with the Germans,’ says Eva. She goes on to say:

There were so many: seven Germans for every one of us. I remember a German soldier who drove a car and he stopped, opened the door and said: ‘Come here.’ My mother let me go and I got some sweets – ‘bonbons’ – from him. Maybe he had a little girl at home, just 3, like I was.

The Germans were clean and polite. They were very handsome men. We used to say: ‘The Germans stole the girls’ hearts, the Russians stole bicycles and watches.’ My mother said: ‘I’m so glad I was married because I am sure I could have fallen in love with one of those handsome Germans.’

At this point Svea leans forward:

There were two types of Germans: the green ones and the black ones. The green ones were OK but the black ones, with the death’s head on their caps, they were no good.

Everything the Germans made they stamped with a German eagle and a swastika. They stamped the sacks of flour. One day a boat with flour and butter came to Kirkenes and was bombed. When the flour sacks floated up our people could grab them and make cakes and bread. When the sack was empty they made clothes out of them. I had a shirt made out of a flour sack, and when I took it off, it stood up on its own.

Kirkenes became vital to German military operations in the Arctic. It was a fortress town, a communications centre for the Litsa Front and the north of Norway and a base for air operations against both the Soviet ground forces and the Allied Arctic convoys supplying Stalin. It was a crucial link in the support and supply chain both into and out of the front line. Supplies and reinforcements went in and the dead and wounded came out, as well as troops being sent on leave or for redeployment. Soldiers wounded on the Litsa Front received initial medical care in Kirkenes and could then be shipped further south for longer-term rehabilitation.

The rapid and dramatic upgrading of the infrastructure of Kirkenes to handle this sudden influx of so many soldiers and so much cargo was carried out by Soviet prisoners captured in the fighting to the east. Kept in camps around the town, the prisoners were used for unloading the constant stream of ships bringing fresh war supplies, as well as on construction and roadbuilding projects overseen by the Nazi construction company Organisation Todt.

The docks became so busy the Germans even built their own railway to transport all the supplies around Kirkenes. Some 800 skilled civilian workers were brought in to build an air base at Hoybuktmoen, 12km from the town, which is the airport to this day. Soviet prisoners built a causeway to the island of Prestøia, which was turned into a military headquarters defended by batteries of anti-aircraft guns with a seaplane base alongside. Around the docks banks of anti-aircraft guns could throw up a fearsome field of fire, supported by artillery both along the coast and sited on the larger islands in the fjords surrounding Kirkenes to the east and west. The sea lanes were mined and U-boats and Luftwaffe bombers searched for targets in the Allied convoys heading for Murmansk and Archalengsk.

Because of the strategic significance of Kirkenes the civilian population found itself on the front line, gradually being bombed into oblivion. Only Malta was bombed more often in the war.

The German defences in Kirkenes were pulverised from the air by Soviet Ilyushin IL-2 Sturmoviks, ground-attack planes fitted with bombs and rockets with a rear gunner to watch their back as they delivered their deadly payload. The Sturmoviks bombed the docks regularly and also attacked German supply convoys in the Barents Sea. They earned the nickname ‘The Black Death’ from the anti-aircraft crews they terrorised and killed.

After one particularly intense attack in July 1944 had reduced much of the town to rubble, many civilians had had enough and left their homes for the safety of the tunnels at the iron ore mine at Bjørnevatn.

Civilian casualties in Kirkenes from the air attacks were mercifully low, especially as the German soldiers had built barracks and warehouses in the gaps between homes. Seven civilians died, among them Eva’s grandfather-in-law. ‘My father-in-law’s father went out on the steps during an air raid,’ she says. ‘He heard planes and wanted to have a look and see where they were heading and he never came in again. One of the bombs fell nearby and the shrapnel killed him.’

I mention the prison camps the Germans set up in Kirkenes for the Soviet prisoners they brought back from the Litsa Front to use as slave labour, building roads, bunkers and bases. I ask if my guests have any memories of them.

‘Near to my house was a camp with Russian soldiers who were prisoners,’ says Knut. ‘When the German guards saw that a prisoner couldn’t work any more they pressed a bayonet into the back of their neck and pushed it up into their brain then twisted it. I saw that.’

Everybody in the room grimaces. Knut looks at me, pausing for Eva to translate. ‘They didn’t use a bullet. They just used a bayonet. Because they couldn’t work any more.’

There is a silence, broken by Eva:

My mother told me that in the winter when it was very cold she saw a Russian prisoner working outside. She gave him a pair of mittens and he thanked her. But then instead of wearing the gloves, he put them in his pocket. Maybe he used them to get some food.

She sighs, and continues, ‘There is a saying: “If you could gather the tears of all the Russian mothers, it would make a river bigger than the Volga”.’

When the peace deal between the Finns and the Soviet Union was signed in September 1944, one condition was that the Finns had to get the Germans off their land within a fortnight. The Finns initially allowed the Germans to move men and supplies by trains and blow bridges and roads as they left, but Stalin tired of the delays and ordered them to use military force. When the Finns surprised the Germans with a landing at Tornio which threatened their withdrawal lines back into Norway the former allies fought bitterly, leaving hundreds of casualties.6

In a glimpse of what lay ahead for Norway, the last SS troops set fire to public buildings as they pulled out of the Finnish capital Rovaniemi in mid October 1944, but the fire spread to wooden private homes, and flames surrounded an ammunition train full of dynamite standing at the station. The force of the explosion wiped out much of the town. By the time the Finns reoccupied Rovaniemi, there was little left standing – perhaps 10 per cent of the town. This pattern was repeated throughout the Finnish settlements along the German retreat. Nearly a third of all the buildings in Lapland were destroyed by German forces withdrawing.7

A week before the burning of Rovaniemi, the Soviets launched the Petsamo–Kirkenes offensive in the northern Arctic, a joint land, air and sea operation setting 97,000 Russians against 56,000 Germans holding positions west of Murmansk. Despite advancing through boggy tundra strewn with boulders, and with hills offering defensive firing points over the single-track road through the battlefield, the Red Army quickly pushed the Germans back to the final river crossing before Kirkenes.

The German commander, Rendulic, had orders to hold on as long as he could so as many supplies as possible could be shipped out of Kirkenes. As the Germans fell back they sowed mines and set up rearguard positions to slow the Soviet advance, but by 23 October 1944 the Red Army was massing for the final push across the Pasvik river at Elvenes and on into Kirkenes.8

The next day fighting had reached the iron-ore mine at Bjørnevatn, only 10km south of Kirkenes. Streams of German columns were leaving town heading west. There were large explosions and fires as stockpiles of supplies and strategically useful buildings were destroyed. By 3 a.m. on 25 October, Soviet troops were fighting in the southern outskirts of Kirkenes. By 9 a.m. they were joined by tanks and artillery moving in from the south. The German rearguard fought pitched battles through the morning with three separate Soviet forces, but by midday the last organised resistance had been overcome. The following day Høybuktmoen airfield was taken and Highway 50 – the only road out – was cut. Any Germans left were forced to flee north to the fjord and escape in boats.

After defeating a German rearguard at Neiden, west of Kirkenes, Soviet commander General Meretskov decided that, with such rugged country and the polar winter on its way and with short days and sub-zero temperatures, the pursuit of the Germans should be called off. The Red Army moved up to the Tana River on 13 November and halted. Kirkenes was free.9

The conversation in my hotel room moves on to the liberation of Kirkenes by the Russians and conditions in the mine at Bjørnevatn.

‘We lived in the tunnel at Bjørnevatn with 3,000 other people,’ says Eva:

I lived there with my mother and father and aunts and uncles and grandparents. Ten babies were born in that time – one of them was my brother. One day I couldn’t find my mother and I shouted: ‘Mamma, where are you?’ and my aunt said, ‘Eva, you have a little brother now.’ We went to a little cottage in the mine and we visited my mother. I can remember this little boy lying beside her wearing a yellow jacket. My aunt had made cocoa for my mother because it was very healthy, and I drank almost all of it. We didn’t have sweet things then. I still remember this wonderful warm, sweet cocoa, and my aunt said: ‘You mustn’t drink all of that because it’s for your mother – she’s just had a baby.’ All ten of those children are living today.

When the Soviet army came there was a celebration outside the tunnel. There was a Norwegian flag outside the opening and there was music and singing – ‘yes, we love our country’ – but I saw something very strange. I saw that people were embracing the soldiers and shouting ‘Oh, I’m so glad!’ Well, I thought that was strange, because I couldn’t tell the difference between the Russian soldiers and the Germans. I had been taught to be angry with the soldiers and now everyone was kissing them!

Everyone laughs. It’s clear the wartime memories are bitter-sweet.

Svea is next to tell a story. On the night of the liberation, her family were also hiding in a tunnel, but at Hesseng, nearer town than Bjørnevatn.

‘My father made beds for us to lie in,’ Svea says:

… and I had a little brother who was born in July 1944, so he was just a baby. That night we went to bed with Germans standing guard outside, particularly one man I remember who was working at a field kitchen. We didn’t sleep very much because of all the noise but then we heard music and singing, and we could see Russians coming down from the ridge – 100, 200! The German with the kitchen had gone, and so had all the rest.

This was 25 October – liberation! By the time the Russians got to Bjørnevatn there weren’t many Germans left. They were all on their way west, to Tana.

Hitler’s order to burn Finnmark was issued only after the Germans left Kirkenes, but there was little left of the town by then anyway. The retreating Germans burned and blew up everything they could – storehouses, roads, administration buildings – and turned their coastal guns on the Soviets before the crews scrambled to escape in boats. Kirkenes was a wasteland, a town in ruins, with a handful of buildings remaining amid the rubble. Charred timbers and factory chimneys poked out of the ruins like bony fingers.

‘Not many people from this eastern part of Finnmark were evacuated because the Germans were in too much of a hurry to get out themselves, so we were allowed to stay,’ says Eva.

Svea nods in agreement. ‘There were twenty houses left after the war in Kirkenes, and they were built for two families to share,’ she says:

We lived in one of the houses that were left and there were forty of us in there, all sleeping on the floor. When you got up in the morning you had to climb over all the other people. But if someone arrived in Kirkenes from the sea, we’d say, ‘Stay with us. Lie down.’ That was in 1945 but after that the town was built back up again.

Eva nods and leans forward. ‘After the war, in 1944 and ’45 there were problems,’ she says:

A few Norwegian soldiers came from Murmansk after we were freed, they were from Scotland, and they expected to be welcomed like heroes. But we were free, and they were not heroes at all. They were angry and irritated. They felt we had been too friendly with the Germans, but we had been living with them for four years. The Norwegian authorities put on a performance of Norwegian fiddle players, Norwegian costumes, just typical Norwegian things, and that was because they wanted to make sure we didn’t forget we were Norwegians because we had been too friendly with the Germans – a rehabilitation. That was a number one policy in Norway.

Many Norwegian girls had German lovers and they had children: Norwegian-German babies. In Oslo they say our sexual morality was very low because so many children were born at that time. History is written in Oslo, and Oslo is too far away; 2,500km is a long way.

When Kirkenes was freed, they raised a flag in Moscow. The rest of Norway knows little about this. The Russians liberated Kirkenes. When the rest of Norway celebrated Freedom Day on 7 May 1945 we had been free for half a year; they don’t know that. This 7 May doesn’t mean so much to us – the important day for us is 25 October – that’s Liberation Day. When the war ended and we saw the pictures of the king coming back, all the flags out in Oslo and everyone cheering and celebrating we said, ‘Oh, this is in Norway – it’s in our country?’

She pauses and tilts her head, almost wondering why this should be. Then she adds, ‘Because it seemed so far away.’

We talk next about the dangers of life in a post-war town recently abandoned hurriedly by one of the best-equipped armies of recent times, which had stockpiled vast quantities of live ammunition in several camps.

Svea’s next story is a tragic illustration of a situation that was commonplace:

After the war there were many very dangerous things left lying around which children played with. There were many young boys without fingers and just one foot.

I had two friends, a boy and a girl. We used to play with the shells they fired from those big guns. Once we had bashed the warhead off there was powder inside; some that was yellow in a flat tube and some that was brown. We mixed it together and tied it up in paper with a rubber band, then set fire to it and ran off into the sea before it blew up. It was very, very dangerous.

One day I had to go to Bjørnevatn 12km away to buy milk and that took all day because I had to stand in line, then I came back on the iron ore train and went back to my Mamma. Mamma said: ‘Oh Svea it was very good that you had to buy milk today because your two friends are dead.’

I went to say goodbye to them. They were laid out in a shed and they looked like they were asleep. But under the sheet covering their head and shoulders there was nothing left. After that day I never played with the shells again.

Eventually our conversation comes to a close. We have been talking for hours. I see my guests out and take a stroll around the town to get some fresh air and soak up some of the history around me. I walk across the central square and past the white parish church (kirke in Norwegian) that gave the town its name. It’s not the original one – that was destroyed in the war – but this new church was built on the same site.

The old harbour is to the left of an ugly modern hotel where tourists stir café lattes while gazing out across the fjord. Moored at the old piers are several battered fishing trawlers – one Russian, one Norwegian. Further along the harbour road and around a slight bend, I reach the dock where cargo ships are loaded with processed iron ore from the processing factory which dominates the hills I am now facing.

The Hurtigruten coastal steamer came in earlier this morning, just before my guests arrived, for its four-hour turnround at the end of its journey up the Norwegian coast. In a couple of hours it will head south again on its neverending shuttle. I’ve been most of the way along the coast on the boat but I’ve never made it to Kirkenes – until now.

The town is still bustling with temporary activity from the boat’s arrival. Tourists can jump into minibuses for expeditions catching king crabs or canoeing down the Pasvik river separating Norway from Russia. Some wander the streets, peering into souvenir shops selling tacky gifts of trolls or sitting on a bench in the small central square smoking or eating sandwiches. The shopping streets have few attractions to hold anyone long: it’s like a British market town on half-day closing in the 1970s. There are a couple of restaurants and cafes, a bookshop, a library and one or two tourist-standard hotels. A kebab van opens up hopefully each day in one corner of the square. The drivers at the town’s only taxi firm have developed patience. Business in the Joker supermarket picks up briefly. There isn’t that much to do in Kirkenes, to be honest, but it’s a long four hours if you don’t do something.

Some tourists find their way to Andersgrotta, an underground bomb shelter a few minutes walk from the town centre. Here you can get a brief glimpse into what happened to Kirkenes during the war. The shelter is open for an hour-long visit three times a day, twice in the morning and once in the afternoon, locked behind a thick steel door facing onto a street lined with yellow and grey wooden houses built in typical Norwegian panelled style, somewhere between sombre and cheerful.

A flight of concrete steps leads down to a gritstone path along corridors hewn from the rock, which open out eventually into an enormous cave. In the war around 800 people from the town sought shelter here. A platform of wooden benches fills the cavernous space, which at 4°C is noticeably chilly and 8m of rock separate the cave from the street above. A white screen fills one wall of the cave, which shows a 9-minute film telling of the German occupation between 1940 and 1944, the 328 bombing raids on the town and the liberation by the Red Army six months before the end of the war in the rest of Europe. Still photographs show German soldiers in the town with their weapons of war, the docks in flames and civilians fleeing air raids. The later sequences show flames licking at the wooden houses, locals embracing Russian soldiers liberating the town’s population at the iron ore mine at Bjørnevatn and then scenes of the devastation inflicted upon Kirkenes. Vast swathes of the town are smoking ruins, punctuated by the brick chimneys rising from the charred timbers. In one picture only the stone steps of the bakery remain. Nine minutes is not long enough to digest what really happened here. And, sadly, some tourists simply don’t believe it. During my time in Kirkenes I hear of American tourists apparently unable to accept that the Red Army liberated this part of Western Europe, and prepared to argue vehemently and unpleasantly until they were red in the face.

When the Hurtigruten steamer’s enormous horn bellows out the ship’s intention to leave, the tourists head back to the new quayside over towards Prestøia. On the way to the boat their minibuses pass more reminders of the war: along the quayside road there are still several ugly concrete bunkers that were once gun batteries and anti-aircraft positions. A wooden house clings to the top of one bunker, known to locals as the former offices of a post-war seaplane company. On the other side of the road is Svea’s old house, rebuilt on the stone cellar blocks she sheltered in with twenty strangers, and now clearly home to a new generation.

I walk to the old piers to watch the final act of the Hurtigruten steamer’s departure preparations. The adventure trips leave from here, just a short distance from the modern hotel. The deep-blue water of the fjord laps against the quayside, gentle waves breaking over jagged concrete blocks broken open to reveal steel wire reinforcements. Rusting in the water are the remains of a narrow-gauge railway goods wagon. Surely this cannot be a bogie from the wartime dock railway?

I am sure that, faced with the obliteration of everything they had worked for, some towns would have built a new Manhattan from their own ashes. The people of Kirkenes cleared up the mess, paved over the war, put up concrete prefabs in the 1950s and became an iron ore boomtown in the 1960s. But when iron ore slumped, so did Kirkenes – and you can almost feel that air of resignation as you walk its unremarkable streets.

The gigantic Hurtigruten steamer bellows for the last time, folds its cargo doors back inside its cavernous hold, slips its ropes and glides without fuss into the waters of the Boksfjord. By the time the waves the boat has made lap and slap against the quayside from where I am watching, it is heading for the Barents Sea and the journey south, and the people of the town are left alone with their thoughts. And what thoughts they are.

There were human settlements in Kirkenes well before the twentieth century but on a very small scale. It was a fishing village with a distinctive white church on its tip that gave the town its name: ‘Kirke-nes’ means ‘church on the headland’.

It was the discovery of iron ore in 1866 10km inland at Bjørnevatn that caused something akin to a gold rush. Thousands of men and their families poured in to work at the mine and seek their fortune once engineers had developed magnetic separation techniques to make mining the ore commercially viable. A railway was built to transport the ore to a plant in the town where it could be separated and then transported to international markets by sea. Port, railway, mine and town all flourished. Swedes, Finns, Russians and Norwegians made their way to Kirkenes to create a community bound by iron ore, enjoying the benefits of prosperity. They built houses for the families and restaurants to cater for the population and numbers swelled, reaching 9,000 by the 1930s. Despite a slump in the 1920s, the mine exported 900,000 tonnes of iron ore in 1938. When the war came, it took them all by surprise.10

There were economic as well as military reasons driving Hitler’s invasion and occupation of Norway in 1940. Exports of Swedish iron ore reached Germany through the port of Narvik halfway up Norway’s Atlantic coast. Seizing Narvik protected this supply, crucial to weapons production – the iron ore at Kirkenes was a bonus. Secondly, the occupation of Norway would deny the opportunity for the Allies to launch a second front against Germany through Scandinavia, something Hitler was so preoccupied with he sent 350,000 men to Norway to prevent it.

The German invasion forced King Haakon to flee to London, along with his government, which operated in exile from there for the rest of the war. Norway capitulated and Hitler appointed loyal Nazi Josef Terboven as Reichskommissar. After several attempts to force the parliament to depose the king, Terboven declared he had forfeited his right to return and dissolved the democratic parties. Norway was now under the direct rule of the Nazis, controlled by Terboven, with a puppet regime in place headed by the leader of the fascist Nasjonal Samling party (NS), Vidkun Quisling.11

The Quisling NS party was roundly rejected by the Norwegian population and never registered any popular support – Terboven had barely disguised contempt for Quisling. In one famous incident in 1942 the country’s teachers rejected en masse attempts to set up a new fascist-led teachers’ union to help Nazify the school curriculum. As a punishment, 500 teachers were sent to work on hard labour programmes building roads in Kirkenes, held in camps alongside Soviet prisoners of war and treated in much the same way. But mass resistance to Quisling’s plan and popular support for the teachers forced him to backtrack, and by the end of the year he abandoned the idea and freed the teachers.12 As a gesture of thanks the teachers paid for a new library to be built in post-war Kirkenes. The building still stands in Kirkenes but it has now been replaced by a new library. The old library is now used as a rest home.

The Nazi takeover and the Quisling regime of collaborators prompted a widespread and defiant resistance, directed from London, organising acts of resistance, sabotage and intelligence-gathering for the Allies. The Norwegian fascists cooperated with and assisted the darkest deeds of the Nazis: rounding up Jews to be sent to concentration camps; setting up its own justice system and force of paramilitary thugs – Hird – based on Hitler’s SA and its own political and secret police; betraying and executing Resistance fighters; and providing guards for the prisoner camps, who shocked even the Nazis with their brutality.13

Allied attacks on shipping off the coast of Norway following the German occupation led to the sinking of several of the Hurtigruten steamers carrying passengers, mail and supplies from the south, and in 1941 the service was suspended, running only as far north as Tromsø.14

The combination of German levies on food and a reliance on imports meant the war had a drastic effect on supplies of staple goods for ordinary Norwegians. Shortages were common and worsened the further north one travelled.

By June 1943 conditions in Kirkenes were deteriorating. Essential food was in short supply and outbreaks of diphtheria, typhoid, dysentery and scurvy were common. Epidemics broke out despite mass innoculations. The basic diet was low in nutrition and calories, consisting of whatever could be found. Meals revolved around herring or turnips: herring soup, turnips with salt fish, turnips with herring – perhaps boiled turnips or turnips fried in cod liver oil. ‘Coffee’ was made from roasted grains or dried peas. Cigarettes were made from discarded stumps found on the streets, rerolled in plain brown paper. People made their own soap from caustic soda and fat. Potato starch was used in cooking and also as a talcum powder. And that was in the good times. The unpredictability of deliveries affected all aspects of life: foodstuffs, medicines, building materials, mail, clothing and even shoes.15

In the following passage, a nurse describes conditions in Porsangerfjord in 1943:

Børselv [a village on the shores of the fjord] ran out of flour a couple of weeks ago, but on the west-side of the fjord it is much worse, as they have been out of flour much longer. Around Christmas there was a ship with potatoes. The westside and Børselv got potatoes but when the ship reached Hamnbukt, frost destroyed the whole load, and so Lakselv, Karasjok, Kjæs and Brenna didn’t get any potatoes.16

There was … a shortage of vitamins. Potatoes were an important source of vitamin C and had for the most part to be imported from other parts of the country. Potatoes transported to the county by boat could be drenched with salty seawater or even frozen on deck before they reached their destination.17

Pregnant women especially had a lower intake of calcium, iron and vitamin C. Medical reports note that ‘one child, one tooth’ was a common saying in Finnmark well into the 1970s.

Though once a plentiful part of the diet for local people, fishing became risky when the waters were mined. Freshwater fish were available with ‘the right connections’. Daily butter rations for the staff at hospitals were the size of a thumbnail and flour was often of poor quality and difficult to make proper bread with. In rural areas, the water came from wells and sometimes small rivers and fjords, but there were health risks here too:

Our teeth went bad. It was the water. We took water from the little lake in the marsh. So did the German soldiers who lived in the cottage in the neighbourhood. They also got bad teeth. Then their officer took water samples from the lake and there was a lot of iron in it, and they stopped using it. They got their water from a brook. We were a big family, and it was too far to bring the amount of water we needed from there, so we still took our water from the lake. And all the children got bad teeth.18

By 1944 the situation had become altogether more serious. The Kirkenes firefighters – volunteers to a man – were expected by their German masters to turn out during air raids and tackle fires, but were not now allowed to take cover. If they did they might be accused of being saboteurs, facing the possibility of imprisonment and even execution. Instead they dug trenches near the fire station so they could find at least some shelter from the bombs, now falling with increasing regularity.19

With the constant daylight of summer 1944, Russian bombers carried out round-the-clock attacks on the German defences dotting the coast around Kirkenes and at Vardø, Vadsø and Berlevåg. There were regular strikes against the big guns of Kiberg, a town across the Varangerfjord from Kirkenes armed with fearsome coastal guns facing onto the Barents Sea, from where they could shell the Allied Arctic convoys.

Much of the population of Kirkenes was living in the Andersgrotta caves more or less full-time by 4 July 1944, when the town suffered a devastating attack from the air. Bjarnhild Tulloch lived in the district of Haugen, a short run away from Andersgrotta. In her childhood memoir Terror in the Arctic she describes how she emerged from the shelter to find her life altered forever:

stumbling from the darkness of the tunnel into bright sunlight was a blinding albeit sobering experience. A strong smell of smoke filled the air. Slowly picking our way through the rubble up to Haugen we looked around in disbelief. The Haugen we knew and loved was almost unrecognisable. It was a beautiful summer day but wherever we turned there were ruined houses and smouldering fires … The destruction seemed to be widespread with smoke curling and rising from ruins where houses had been.

Our house was still standing, but only just. The house diagonally across us from the square was gone, blown off its foundations. The house across from our kitchen had burned down. The steps and landing [of our house] had disappeared and the outside door was missing … Where there had been windows, there were now only gaping holes. The walls were peppered with shrapnel and there were signs of fires having been put out. The floor was covered by a thick layer of pulverised material, which had been all our dishes and food, and probably the window as well. The kitchen table and chairs, along with the rest, had been turned into rubble. One cupboard door, left on the wall and peppered with holes, was swinging slowly from one hinge. We were now destitute. All we had was the clothes we were wearing.20

In the library across the square from my hotel I’m looking through a book of pictures from the wartime occupation, which deals in some detail with the fighting on the Litsa Front. The book is called Kirkenes–Litsa by Kalle Wara. The scale of the German presence is enormous. In one picture a ship at the docks has unloaded twenty-four artillery field guns which have been lined up side by side on the quayside I walked along earlier this afternoon. There are barrels of fuel and oil and sacks of food as high as the soldiers beside them. Perhaps Svea’s shirt was made from a sack like this. In the background I spot the old school house that was taken over by the Nazis and destroyed by Russian bombing. Other pictures show thousands of soldiers on parade, tanks driving away from the docks and 300 horses in make-shift stables being fed before being moved to the Litsa Front. The Germans would find the tanks of little use. Facing enemy artillery on a single road surrounded by swampy marshland and rocky tundra, lack of manoeuvrability under fire would become a key issue. They were soon withdrawn from a combat role.

I turn another page. Here there are Stuka dive bombers on their way to attack Murmansk, horses and reindeers pulling supplies in snowstorms and a column of trucks loaded with soldiers driving along a waterlogged, muddy road led by a motorcycle sidecar outrider. The next picture shows a U-boat slipping into Kirkenes from a patrol hunting Allied supply ships heading for Murmansk – the photo alongside shows black smoke belching from one ship hit by Luftwaffe bombers.

Another page shows the aftermath of a Soviet air raid. A bomb has torn the entire end from a wooden house. Wallpaper peels from an upstairs bedroom wall and there’s a pile of timber and unidentifiable belongings in a sad pile outside. Another house has had its back broken by a bomb blast. The front has collapsed while the back has reared up on its foundations like a sinking ship.

Another photograph shows the aftermath of a direct hit by an incendiary bomb on a timber store at the docks. Thick black smoke and flames rise high into the sky. Hundreds of people look on from a safe distance, but the smoke is so dense and the picture taken from so far away I cannot distinguish with certainty whether they are Germans, prisoners or civilians, but, judging by the ship standing off the quay, that looks like where I stood an hour or so ago watching the Hurtigruten steamer leave.

At the back of the book I find a series of maps showing the German defences around the town. Kirkenes certainly lives up to its billing as a fortress. There are searchlights and air defence guns all along the coast, dotted around the fjords and inlets. There are three airfields: Høybuktmoen in Kirkenes, Bardufoss near Tromsø and, in between, Banak near Lakselv on the Porsangerfjord. There are marine bases and barracks for 10,000 to 15,000 men for the coastal defences and the 45,000 men going to and from the Litsa Front. Ships or aircraft approaching Kirkenes would have to run the gauntlet of a network of coastal artillery guns that packed a deadly punch. Across the fjord at Kiberg there were three 28cm cannons. An island in the centre of the fjord facing Kirkenes had four guns which could point either out to sea or at the town.

The town itself was guarded by a coastal battery of three 15cm guns. There were air defence batteries of four 88mm guns in three separate places round the town and coastal air defence guns on the beach, with vast storehouses and ammunition dumps in several places round the town. Up near the three lakes heading out of town towards Murmansk, marked with barbed wire, was one of the biggest prisoner of war camps in the area, a ‘fangeleir’. There were minefields, bomb stores, ammunition dumps, barracks, workshops, coastal bunkers and seaplane harbours ,including the one alongside the fortress island of Prestøia.21

Great thought and vast amounts of effort had clearly gone into the defence of Kirkenes, and it’s not difficult to see why. The town was the centre of the German command structure along the coast of Finnmark and to the Litsa Front in the east, linking to the front-line troops both in Finland and the areas of the Soviet Union under German control. A network of telephone cables laid across land and undersea connected Kirkenes with coastal batteries at Vardø, Kiberg, Vadsø, Bugøynes and along the coast to east and west. Knocking out the communications centre in Kirkenes would have dealt a severe blow to the effectiveness of the German army along this whole front.22

From the library in the town centre I walked up a steep hill to the Borderlands Museum (the Grenselandmuseet) which overlooks the town. Here I would get an insight into the war through the eyes of the Soviet pilots sent to attack Kirkenes and who had to fly through fearsome defensive fire to deliver their bombs.

The museum is an amazing place, being built around one of the few remaining Sturmovik ground attack planes. It was ditched in a fjord during the war and remained there for forty-five years before being rediscovered. When it was salvaged the Russians took it back across the border, restored it free of charge and then presented it to the people of Kirkenes. The two-seater plane, painted blue on the underside and camouflaged a mottled green above, with a red propeller spinner and a reindeer with antlers painted just below the cockpit, fills the main hall. The pilot for its final flight was Alexander Chechulin, commander of a squadron of Sturmoviks from the 214th Airborne Assault Regiment in 1944.

‘I remember Kirkenes very well,’ he said in an interview after the war. ‘Every time we flew over Kirkenes there was so much shooting I had to close my eyes. When you are the first to attack you close your eyes, then you open them and let the bombs fall. We would fly over again to take pictures before returning home.’

The Germans hated Sturmovik attacks, hence the nickname ‘The Black Death’. One captured NCO told Russian interrogators, ‘The Sturmoviks were what the soldiers dreaded the most. When they appeared both soldiers and officers spread out seeking shelter wherever possible. Almost everyone is convinced the Russian planes are better and that the Russian pilots are more skilful and braver than the Germans.’

Another NCO prisoner said, ‘The aircraft’s effect on morale was enormous. Anti-aircraft defences covered the battery for fear of attracting the attention of the planes. In fact it took hours to calm down the aircraft defence squad after such an attack.’ And yet another soldier said, ‘Everyone hides behind rocks in fear, waiting for the planes to pass over. After the attack they thank God they are alive. One does not wish either friends or enemies the terror of such moments.’23

The following morning a tall man wearing a black and white check shirt takes his place on the sofa in my hotel room. Rune Rautio is a Second World War military historian specialising in the Arctic Front war. One of my new Norwegian friends put his number into my hands and suggested I call him. From his very first words I can see that his expert knowledge will answer some of the questions gathering in my mind.

‘The scorched-earth order to destroy everything was first given by Hitler on 16 October, a week after the start of the Petsamo-Kirkenes offensive,’ he says:

That was an order that the German troops should withdraw after destroying their own buildings and fortifications, but it didn’t specify destroying the civilian houses. Then Hitler changed his mind and ordered the destruction of all civilian property. That was issued on 28 October but because of communication difficulties the troops didn’t receive the order until the following day, and by that time the Germans were long gone from Kirkenes.

There wasn’t very much to burn in Kirkenes by then anyway, especially after the Soviet bombing of 4 July. The Russians dropped cluster bombs, incendiaries and 1,000kg bombs which ruptured the water pipes so once the fires took hold of the wooden houses they couldn’t be put out.

The order on the 28th was too late for Kirkenes to be classified as a ‘scorched earth’ destruction – it arrived after the liberation by the Russians. By then the Germans had left for the west, and it was only after the Battle of Neiden several kilometres outside Kirkenes that the Germans began what you would describe as a scorched-earth retreat; that is, burning everything in their path. They started burning on the 28th, so the first place that was burned according to the instructions was Bugøyfjord, a small village between here and Varangerbotn.

Many people round here will tell you that the relations with Germans were good and even very good, as you had reservists manning the coastal fortifications in small places. They were older, family men with a wife and children at home, mature, and they came into close contact with the civilians. Many of them established relations that would last the rest of their lives.