Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

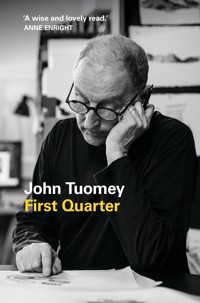

In this reflective and enriching memoir, John Tuomey navigates the places and memories of his life over the scope of twenty-five years. First recognised for the urban regeneration of Dublin's Temple Bar, which included the construction of the Irish Film Institute, the National Photographic Archive and Gallery of Photography, his life in architecture led him to design social and cultural spaces such as the Lyric Theatre in Belfast, the Glucksman Gallery in UCC and the Victoria & Albert East Museum in London. Imbued with many inter-textual references to poetry, drama and literature and written in limpid prose, this memoir is inherently literary in nature. Tuomey looks back to his early life where he was born in Tralee and lived in different counties around Ireland, from small towns to country landscapes, from schooldays in Dundalk to student activism at University College Dublin. He traces the pathways that led to his formation as an architect, reflecting on the many cultural and social influences on his life. He excels in capturing the social landscape of Dublin in the 1980s and pays particular attention to the many buildings and social hubs of the inner city. His transient years of moving from Dublin to London, and subsequently working in places like Nairobi and Milan, chronicle the international influences on his outlook. The key relationships in his life, including meeting his future wife, Sheila – a fellow student of architecture in UCD – and his pivotal employment by James Stirling in 1976, form the backbone of his personal and professional life. Tuomey's expertise in his field is unsurpassed, with meticulous detail given to the finer aspects of design and architecture. His thoughts on the challenges facing the encroaching erasure of city life in Dublin are essential reading for anyone with an interest in the future of building in the city.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 228

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First Quarter

For my siblings, my sons, my Sheila.

John Tuomey

First Quarter

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

First published 2023 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road, Arbour Hill

Dublin 7, Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

Text and illustrations © 2023 John Tuomey

ISBN 9781843518747

eISBN 9781843518907

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

A cip record for this title is available from The British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Lilliput Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the

Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon.

Set in 11pt on 15pt with Adobe Caslon Pro by Compuscript

Printed in the Czech Republic by Finidr

Contents

Preface

Ten Years’ Time

Far from Home

You Don’t Know Me

Dancing about Architecture

Dublin Dimensions

In and Out of London

Learning from Stirling

Let Us Go Then

Looking Back

Looking Out

Acknowledgments

O’Donnell + Tuomey: Selected Works 1991–2025

Every generation goes its own way and remembers only those things it wants to remember.

Roy Jacobsen, The Unseen

Preface

At it again, with your I’s and me’s!

Stendhal, The Life of Henry Brulard

I HAVE NO BACKGROUND in architecture, apart from my father’s building sites. Both my parents came from well-established, solidly middle-class shopkeeping stock. And yet I feel that my identity, the first and last thing to say about me, is that I am an architect. Become one, not born one, but an architect through to the bone.

How did this happen? Simple to say. I went to university when I was seventeen years old to find myself transported, suddenly, into my natural world, a life-world that was waiting. I knew right away.

My mother, at nineteen, had slipped away from her Limerick business upbringing, dodging the prospect of joining her father, Jack Walsh, in his fire-lit office at Cannock’s department store, where three of his daughters went to work, where he had followed his father. She left home to take up a job in the bank, moving digs all around the country town circuit, feeling independent and fancy free, until she fell in with my father at a tennis party in Tralee. She brought me up, from my earliest days, with the idea instilled of self-reliance. Moving on, moving out.

A new life in architecture lay ahead of me. Everything before was behind me. Time to move on, I said to myself, with never a backward glance. Until now. Not so simple, after all. Here I am, trying to piece together a mosaic of places and a partial history of events, trying to recall what it was that might have made me what I am. Now, well past the midway point, to remember before I forget. Where I came from. How I found my way from there to here. Not to here exactly, but up to the starting point that brought me here. Here I am.

Ten Years’ Time

It is not the literal past, the ‘facts’ of history, that shape us, but images of the past embodied in language.

Brian Friel, Translations

I DON’T REMEMBER, CAN’T remember, the house where I was born. Not that I was born in a house. I was born in a hurry at the Bon Secours in Tralee. My mother didn’t have time to remove her sheepskin boots, or so the story goes. The little house I was brought back to faced Fenit’s main street. Folded in under the roof was a veranda; this is known to me only from one tiny black-and-white photograph, with my father, ever the gardener, ministering to, admiring perhaps, a very large cabbage. He’d been working for more than two years as site engineer for the new Fenit pier, an elongated isthmus leading to Europe’s most westerly deep-sea harbour, not five miles from his family home at the Spa. I don’t know, and it’s too late to ask him now, why he took this, his first job, so close to his original home place, when he’d been so far away all through the war. The new family, my mother, father and firstborn sister, lived on a daily diet of lobster, my father being known locally as ‘Lobster King Tuomey’ for his luck with the pots. Spartan luxury.

Then there was Macroom, where we moved when I was six months old, my father this time working on a town water scheme. We lived in a plain-fronted terraced house on Main Street. There was a long back garden, a narrow strip between high walls, where he grew vegetables. I have a dim, or dimly received, memory of very large marrows.

Images begin to take shape, still hazy but a little clearer, from our days in Drumshanbo, where we once again rented a terraced house on the main street. Here my father was stationed to build new structures for the coal mines at Arigna, an electricity-generating power plant built to burn the locally mined fuel. One day he brought me inside a very tall chimney, looking up together through the tapering shaft to a little slot of sky, him telling me about the constellations, so it must have been evening time. The Plough pointing to the Pole Star, the Seven Sisters in a huddle, Cassiopeia like a big W, Sirius the Dog Star, the brightest star in the sky. These lessons in basic astronomy continued across camping holidays and from the kitchen step on summer nights.

I began my schooldays in Drumshanbo. The schoolmaster, in a gesture of welcome, showed me how to milk his cow. Warm air inside the dark cowshed, warm milk in a bright bucket. Another day, on the way home from a shopping trip to Carrick-on-Shannon, I threw my new shoes out of the car window, silently, one at a time, each at some distance from the other along the country road, this careful tactic adding, I’ve been told, to my parents’ frustration. My older sister’s back seat of the car frustration lay in trying to teach me words, with instructions to repeat after her … Cow, Cow. Horse, Horse. House, Outhouse. I don’t know why it infuriated her so, my insistence on outhouse, but then again, I’ve been told, it worked time after time. Still, it’s a nice word, outhouse. Sometimes you can make yourself believe you’ve invented or discovered even the simplest of words, a sudden moment of epiphany. I remember wasting time as a student thinking about the etymology of the word diagram, the diagrammatic clarity of the word itself, already marked out in lines.

There was some sort of arrangement with the landlord that, on market days, he could pen his sheep in the hall of our house, lining the floor and halfway up the walls with corrugated sheeting. We looked out of the front window at wall-to-wall sheep, sheep spread across and up and down the street. Could this be true? At the back was another high-walled long garden where my sister and I climbed along its stone ledge, made snowmen with tin hats and coal buttons and, again, my father grew his vegetables. Visions of the Virgin and Child appeared over the wall, blurred and radiant figures shimmering in our neighbour’s round-arched landing window, worrying me: what was She trying to tell me? After my mother took me to get my first pair of glasses, those disconcerting visions disappeared for good. Sliding down the stairs on a tray and shunting the tray-train into its station under the kitchen table, my own private station for ego-stretching and pestering exchanges with my ever-attentive mother. Who would I be, where would I be, without the sense of purpose driven deep by my mother? She came home from Sligo with the new baby, my middle sister, who still believes she belongs in the west. So now, on the long drive back down south, we were three in the back of the car.

That long drive was to Cobh, where my father’s company had the contract to build new ground for the Haulbowline Island steelworks. From Kerry to Cork, to Leitrim and back to Cork, four house moves through three counties by the time I was five. In these place-based recollections of childhood, memories from Cobh come more strongly into focus and are more likely to be first hand, their reliability tempered only by the normal distortion of six decades’ distance. If they are not really all true, they are all certainly real. Our street-fronting flat led back to a tiny yard where a red sandstone rockface ran weeping with water. No room for vegetable growing here. I slept on an iron frame bed in a side pocket off the hallway, a bed-sized alcove in the undercroft of the stairs to the upstairs flat. I lay defended by a wooden sword laid across my chest, made for me by my father, bluntly pointed at its white-painted tip, sanded off on its second day to a safer chamfer, its hilt painted silver and gold. I was not scared in the dark, not until the night when, brushing my teeth in the bathroom at the end of the hall, I glimpsed in the mirror a hooded figure loping out of the gloom. I turned round to see this creature bounding up behind me, long arms swinging low to the floor. My heart jumped. The bogeyman leapt sideways into the shadow. Out stepped my laughing father, his human face half-hidden by a monkey mask, removing the disguise of his oversized duffel coat. His joke, not so funny for me.

Our first Cobh Christmas delivered a handmade redpainted wooden train, steam engine and carriage, solid enough to sit astride and ride around the flat, but not for the outdoors, the street being too steep to go railing. Harbour Hill is a really steep street, running down and around a dogleg bend to the small harbour at the centre of town, where my father kept a shiny varnished sailing dinghy, Shearwater II – was there ever a first to this second? It was our only boat, and leaving it behind when we moved again was a blow to the heart. One day, I noticed a carton of golf balls in the bottom of the boat. One by one, I dropped them in the water, announcing, with the empty box held out as evidence of a successful experiment, ‘ Daddy, I’ve news for you. Golf balls don’t float!’ No ice cream that day.

The day of the ice cream was when I tripped over a stray rope while trying to pull the dinghy up the slip. I was picked up crying, with scraped hands and knees, a bloodied nose, a sore and swollen upper lip, by my aunt, my mother’s younger sister, who was staying with us at the time. She brought me into a little timber-boarded sweet shop across the road from the pier and bought an eight-penny wafer, the biggest I’d ever seen, intended, I now suppose, to reduce the swelling. Opened up out of their boldly striped red and white packaging, those blocks of vanilla ice cream would have been carefully marked out in scored lines ready for dividing. Shopkeepers had a special trowel-like gadget for doing this, three-penny slices being the usual measure on a Sunday after mass. I’d broken my front tooth in the fall, so that extra thick treat brought more nerve pain than pleasure that day, but a memorable pleasure nonetheless. Another day we sailed all the way around the sheer-sided hull of the two-funnelled Mauretania as she was towed into harbour. We bobbed with excitement in her wake. Years later, in London, watching Fellini’s Amarcord, with all the awestruck townspeople out in their boats, waiting in silent rapture for a passing liner’s emergence out of the dark, brought me sailing back to Cobh.

That patient aunt, on this or another visit, was to reveal a particular flaw in my character, a persistent flaw, one not to be proud of. Pride. Noticing my interest in her knitting patterns, she sat down beside me, with needles and wool, and gently offered to show me how to knit. I stood up and made my escape, declaring over my shoulder, ‘I can knit!’ This moped-pedalling aunt was an unusual woman, independent living, chain smoking. She enrolled me for an annual subscription to Animals magazine, with its own embossed and rigid folder to bind all the weekly issues in neat order. She always arrived with interesting books: The Social Life of Animals, by Marcel Sire, with its description of forty thousand bees working together in a hive, made a lasting impression.

She drove up from Limerick to mind us five children when I was twelve, a few years after the family had moved to Dundalk, while my parents went off on their first non-family holiday, two weeks in Venice. On the first day we clashed over boundaries, she being too strict, or maybe too careful, never having looked after a houseful of children, me demanding to spend the long summer days unstructured by any aunt-imposed lunch or dinner schedules. I hot-headed for the door and cycled off to the Blackrock baths for a cooling swim. That same day my bicycle was stolen from outside the swimming pool. I tramped the four-mile journey home, lamenting that surely my hard-won freedom would be severely curtailed. My aunt promptly placed an ad in the local newspaper, simply asking for information leading to the bicycle’s return. The next day, I received a mysterious letter from an unnamed Redemptorist, asking me to call to the monastery if I wished to learn something to my advantage. I turned up at the appointed hour, cryptic letter in hand, and was surprised to be led to a dark shed full of discarded bicycles. Bicycles by the dozen, I was told, dumped daily over the monastery wall by boys spinning home from the pool, ditching their borrowed wheels as they crossed the railway bridge back into town. I could pick any bike, but my own shiny Raleigh was ready and waiting. Independence was re-established, and relations with my aunt much improved.

Years later, while my mother was minding her ailing sister, I volunteered to investigate how to fulfil her last wish. I made an appointment at the Royal College of Surgeons, just a short walk from our Dublin studio in Camden Row. I was ushered to a small office upstairs, where a woman welcomed me, invited me to sit down and tell her what was on my mind. I explained that there was this aunt, who now lay dying in a Limerick hospital, how she had worked for doctors in her youth and always took an interest in science, and now she wanted to donate her body to medical science, not that I knew her very well, just wanted to help, none of the family was familiar with the procedure and I was here for any useful advice on what needed to be done. The kindly faced woman softly shut the door to the corridor, turned towards me with sympathy and compassion in her eyes, shaking her head slowly. ‘There is no aunt in Limerick, is there? It’s yourself, isn’t it, it’s you are the one who’s dying. Why don’t you tell me all about it?’ I was stunned into silence by this strange experience. Once again, as often seemed to happen around this particular aunt, I stood up and made my escape.

My aunt’s remains eventually landed in the pathology lab at University College Cork, the old anatomy building we have since redesigned and adapted to livelier purposes as a student hub. And a year or two after her deposition, I arranged the transfer of her coffin to Rocky Island, a crematorium most cleverly converted from the magazine fort, entered through tunnels cut out of the rock, a quiet place with beautiful vaulted brickwork and a sense of calm isolation, a feeling of final destination enhanced by the way it stands open to the water’s edge. And so, in the end, at her end, I returned with my adventuring aunt to the wide bay of Cork Harbour, where we had sailed together when I was six.

Seen from the sea, from where it must surely have been designed to be seen, Cobh is tightly spread against the hillside, terraces stacked over each other, the vertical line of the four-stage cathedral spire keeping the whole pile-up pinned in place. Harbour Hill leads down in the direction of the Holy Ground, where the rough boys were rumoured to gather. From our doorstep, I witnessed a running group of lads with a rope stretched loosely between them from either footpath. A flick of the rope was enough to lasso passing girls, one after another, all looped together and trotting down the centre of the street in their summer dresses, the way the cowboys rustled wild ponies on the plains.

Coming home from school, in the shadow of the vast cathedral where I made my first holy communion, at the foot of the steps under its railinged walls, I was a few times set upon by a small gang closer to my own age. They wanted either my banana sandwich or my cardboard crown. They swung me to the ground by the second coat worn buttoned at the neck over my real coat, a flying cape to match my crown. I came home intimidated by what looked likely to become a pattern of low-level bullying. Indignant, dragging me with him, my father leapt into the car. He drove down the hill in pursuit, pulled up across the pavement, stepping out into the path of this little hooligan troupe to promise, in words I’d never heard him say, his hand raised like a hatchet, that he would split them from head to toe. No more trouble after this warning, not from that quarter.

One fine day I fell off a beach-facing cliff. An overhanging tuft of grass gave way and I dropped down some twelve feet to land, luckily, on a small patch of sand between jagged rocks. Broke my ankle in two places – ‘That fellow will always land on his feet,’ said my father to my worried mother. I learned to adopt a loping trot, like Long John Silver, hopping up and down Harbour Hill, one leg up on the padded knee-rest of my wooden crutch. The day my foot was released from its plaster cast, my father broke the crutch over his knee and burnt it in the fire. I felt bereft, deprived of the advantage of my pirate’s prop.

Two doors up the street lived my first love, who one day needed to be rescued from the railings where the postman had her loosely tied by her long skinny plaits. The postman was known for such tricks, but this one gave me the chance to be useful. We used to dress up in brown paper vestments, she and my sister and I, taking it in turns to say mass, or concelebrate high mass together, arrayed side by side on the steps of her hallway. Her ancient aunt stood every day like a statue in the kitchen with her skirt pulled up, warming her backside against the range. The day of her auntie’s death, that bold and lively girl led me upstairs through a house crowded with black-suited mourners, to feel with my fingers the stone cold of a dead woman’s forehead.

In my father’s typical style, with no explanatory words, he showed me how to ride my new red bicycle. Sat up on the saddle, feet set on the pedals, released at the top of a steep country lane, gaining speed in gathering panic, until, hands sweating, halfway down the gravelly hill, I pulled the front brake and turned over into the ditch. A scary start, sure enough, but I’ve never been without a bike since. I seem to think more clearly, believe myself in better balance of mind and body, when I’m up on a bike. Models come and go, dropped handlebars and racing frames are probably gone for good, but being in possession of a bicycle remains a pivotal part of my sense of identity.

Years later, teenage driving lessons with my father followed a similar pattern – finding out how to fend for yourself. He drove out one Sunday afternoon to a disused industrial estate. We swapped seats for a short demonstration of brake and accelerator with the right foot, clutch with the left. Then he stepped out of the car, leaving me at the wheel with only minimal instruction on gearstick manipulation. I can see him still, standing on the concrete road, smoking his pipe, watching calmly while I reversed his car right off the road and revved up onto a gravel mound. Lessons learned from my father, man of few words.

Four of us now, crammed into the back seat of the new Simca, all the way from Cobh to Cooley. My brother still laments having been translated out of his native county of Cork. Everything changes from black and white to colour with our move to Cooley, the crucible of my boyhood self-reliance. These days, that change in tone still happens, but now in reverse, since the field pattern of the Cooley Peninsula feels older than the ages, the rural landscape seems to belong in black and white. But in those crucial days, the whole scene shifted into Technicolor, coinciding with the dawn of my consciousness, the beginning of life as an individual. Or maybe that realisation only sank in on the upstairs balcony at the Carlingford cinema, Spartacus climbing over the railings of his captivity and The Magnificent Seven with its magnificent theme music. Many movies since have made lasting impressions, but these were the instigators.

We settled into a plain and ordinary two-storey farmhouse, no farmland with it now, still a proper country house with walls and gate piers, red corrugated sheds and whitewashed outhouses, iron gates and compartmentalised gardens ready for my father to plant his vegetables. We kept chickens, ducks, rabbits, many cats, the occasional hedgehog held overnight under a galvanised bucket. On its road side, Hillview looked over a low mountainy prospect up to Maeve’s Gap, ready every morning for the Gaelic queen to ride out of the mist into a new cattle raid. The outriding walls were integral to the house, indivisible from the main structure, long walls leading to promontory gate piers, bastions of outlook to nearby fields and faraway hills. Straddling the wall outside the back door, with two breakfast cereal boxes strung behind for saddlebags, the gate pier was your horse’s head, straining for the open country. Standing on the furthest pier, you were a pirate’s boy sent to the crow’s nest to keep a weather eye on the horizon for passing ships. Behind the pebbledash boundary walls, the house was surrounded by a time-woven tapestry of odd-sized fields, each one soon named: the Green Field, the Big Field, the Far Field. Over the rise beyond these differently shaped plots were big patches of brambles, tangled underworlds, one with a drystone sweathouse, tiny, overgrown, earthen-floored, but spacious enough to crawl into and waste away the day. And beyond that, too far to walk to but not too far to wonder about, lay the sea, the sloping sandy beach and the eastern horizon. On a clear day you could see the Isle of Man from the nearest hill.

The house itself a simple double-fronted block with brick chimneys on the gables. Central narrow hall, single-flight stair. My room upstairs, roadside, on the north-west corner, watching Maeve’s Gap. The front garden, seen from above, lay in two lawns divided by a narrow concrete path from a red-painted gate, never used, leading to a snout-projecting porch and front door, likewise never used. Upstairs I set traps for my sister, standing on a chair to place soaking wet sponges strategically balanced over her half-open bedroom door, her door across the hall from mine. Once I threw her teddy down the hall from the top of the stairs. She ducked, the teddy smashed through the window, just as the farmer from down the road, known only as Mr Mac, was cycling by, coming in to see how we were, my parents being out. He diplomatically cleared the broken glass off the porch roof and courteously retrieved my sister’s teddy. Not all my fault, he agreed. My aim was good, my sister’s fault for ducking.

Any callers came in the big gate at the side of the house, across the main yard, through the small gate to the back yard, up two steps to arrive, unannounced or uninvited, straight in the back-kitchen door. A pulley drying rack hung from the kitchen ceiling, over the Rayburn range. The main clothesline ran across the yard, squares of laundry useful for bow-and-arrow target practice, until my sister appeared from behind a flapping tea towel with a floating arrow caught in her cheek, just below the eye. Target practice moved on to duck eggs lined up along the top of the wall, a more demanding job and best tackled with a catapult. My weekly housework, apart from mealtime washing up with my sister – you wash, I’ll dry – was to hoover the hall and stairs, polish the brass knocker of the unused front door, polish the bent parallel lines of copper pipework in the bathroom, polish the family shoes ready for Sunday mass. My father made the sandwiches for our school lunches and for his own lunch at work, cooked the chicken for Sunday lunch and the turkey for Christmas dinner. Otherwise, assuming my sisters did no work – they had no regular duties that I can recall – my lively mother ran the house. I ran all around that house with my mother, chased her for sport, until the day of her fortieth birthday, when shocked by her age, I decided she was too old for dashing about after her boy.

It wasn’t too far to walk to school, maybe another mile beyond Maguire’s Cross, but some days needed an early start. Each week, one boy was selected, given the honour, to come in half an hour before school to set and light the stove. It was a two-storey schoolhouse, standing foursquare in the shadow of a disused railway bridge over the road to Grange. Our classroom was on the first floor, accessed by an outside stair, one of two rooms subdivided by a glazed partition. There were a few rituals worth recording here.

The first offender of the week would be asked to go out along the roadside, entrusted with the teacher’s penknife, to cut a sally stick from the hedgerow for his own punishment and, inevitably, for others’ punishment to follow. Too small a stick and the teacher would go out and choose his own, too heavy and everybody suffered, so, by an unspoken understanding, every stick got cut to something like a standard size. Except once, as I recall, when some joker brought back a long and wavy sapling, thinking it too unwieldy to be useful. It turned out to be the worst week for stinging smacks. That springy stick, flicked like a whip from the teacher’s station, could reach any ear on any desk at random. Our desks were long benches, four to a row, with sunken inkwells filled daily, blue ink carefully poured out from a big bottle of Quink, another privilege designated weekly.

A central spine wall divided the schoolyard between boys and girls, with the toilets in a lean-to shed built against the back wall, just under the railway line. A continuous wooden seat ran between stalls, with circular cutouts over an open drain. That drain, by gravity’s natural fall, joined the boys’ yard through to the girls’. A small flat stone, pegged at the correct angle through one of the holes in the bench, could be aimed to skip along the drain and, on a good day, splash up the innocent backside of an unseen target. In this game of chance, calm and unidentifiable, you simply waited for the scream.