7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Lightning Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

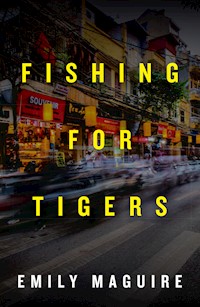

'An emotionally gripping and page-turning read' SYDNEY MORNING HERALD Six years ago, Mischa Reese left her abusive husband and suffocating life in California and reinvented herself in steamy, chaotic Hanoi. In Vietnam, she finds satisfying work and enjoys a life of relative luxury and personal freedom. Thirty-five and single, Mischa believes that romance and passion are for teenagers; a view with which her cynical, promiscuous expat friends agree. But then a friend introduces Mischa to his visiting eighteen-year-old son. Cal is a strikingly attractive Vietnamese-Australian boy, but he's resentful of his father, and of the nation which has stolen him away. His beauty and righteous idealism awaken something in Mischa and the two launch into an affair that threatens Mischa's friendships and reputation and challenges her sense of herself as unselfish and good. Set among the louche world of Hanoi's expatriate community, Fishing for Tigers is about a woman struggling with the morality of finding peace in a war-haunted city, personal fulfilment in the midst of poverty and sexual joy with a vulnerable youth. 'Fishing for Tigers is a sharply observed novel, both page-turning and thought-provoking. It vividly evokes the particular beauty of Hanoi, the intoxication of being a stranger, and the danger of desire.' NEWTOWN REVIEW OF BOOKS

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Published by

Lightning Books Ltd

Imprint of EyeStorm Media

312 Uxbridge Road

Rickmansworth

Hertfordshire

WD3 8YL

All rights reserved. Apart from brief extracts for the purpose of review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without permission of the publisher.

Emily Maguire has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as author of this work.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Innocence is like a dumb leper who lost his bell, wandering the world, meaning no harm.

The Quiet American, Graham Greene

Contents

I

II

III

Acknowledgements

I

When I’d told my sisters I was moving to Vietnam without a job or a plan, they were divided on what this meant. Margi thought I was having a breakdown and God knew what would happen to me in a foreign country in such a vulnerable state. Mel said that I’d broken down years ago and that there wasn’t much worse that could happen to me than my marriage to Glen. One thing they agreed on was that I needed to find myself.

My intention was the opposite. I wanted to lose myself so thoroughly that I would never find my way back. I had picked Hanoi because the airfare was cheap and I knew almost nothing about the place. The need to be swallowed up by strangeness was the closest thing to desire I’d felt in years.

In my first months there I had taken long walks and bike rides, caught cyclos and motos and taxis. I rode dust-caked, overflowing buses to outer districts where my red hair incited impromptu street parties. I felt constantly lost but began not to panic about it. Each night as I slept, the new streets were inscribed onto the map in my mind and almost without my noticing, Hanoi lost its strangeness, became home.

Even now, sometimes when I wake, I lie with my eyes closed and trace the streets in my mind, searching out new short-cuts, getting lost and found. The city is always as it is after a thunderstorm, shiny and clean and steaming. Schoolgirls giggle and wring out their shirts and the street vendors glance at the sky before whipping away their makeshift tarpaulins. The air is thick and damp, smelling of rotting fruit and fish sauce and exhaust. I wander until my mental map runs out of streets and only then do I let myself wind back in to the centre, back to the apartment overlooking the cathedral and the boy stretched on the bed, as cool and toxic as the rushing Red River.

***

Matthew had booked the roof garden at KOTO, which was where we always went to introduce newcomers to our circle, because the menu was westernised, the drinks were strong and the staff spoke at least a little English. They were all former street kids, so we got to feel magnanimous as we indulged. Matthew had asked, in his calm, charming way, that we not over-indulge tonight. The guest of honour was his teenaged son, not some newly imported slab of fresh meat.

It was obvious to the rest of us that the request was meant especially for Kerry who had been in Vietnam three years, but acted like a twenty-year-old backpacker who’d arrived from Liverpool that morning. On this night she was wearing a pink and black sarong twisted into a skirt and a clingy black singlet. Her long blonde plaits were tied with ribbons the same candy-pink colour as her nails and lips. She’d arrived ten minutes ago and had already ordered a second daiquiri. ‘If you’d seen what I went home with last night you’d understand,’ she said when I suggested she try to remain sober at least until Matthew and his son arrived. ‘God, I wish I could lose my sex drive.’

‘I have the solution to all your problems, my love,’ said Amanda, sliding in beside Kerry and taking a sip of her beer. Amanda was a university administrator who dressed like a rock star. That night she wore dark jeans and a tight black shirt with rips down both sides.

‘I’ve told you before, Mandy, you’re a babe, but I just don’t swing that way.’

Amanda, who had a new and hotter girlfriend every week, had the grace to look disappointed. ‘In that case, you’ll have to go with the second-best option. ElectroMart on Hang Bai sells these neck massagers. You know the battery-operated vibrating kind with a big, hard knob on the end? Thirty bucks and you’ll never need set foot in the backpacker district again.’

‘Who’s been in the backpacker district?’ asked Henry, bending to kiss my cheek.

‘Kerry,’ I told him.

‘Oh dear. Trolling for Euro-trash again?’ He draped his leather jacket over the back of the chair beside me and then sat down with his designer-jean clad legs spread wide-enough for even a western-sized woman to stand comfortably between them.

Kerry drained her glass and waved at the waiter lurking in the doorway. ‘Easy for you to scoff, old man. You only have to stand outside after sundown to get laid. We tây ladies aren’t so lucky.’

‘ElectroMart,’ repeated Amanda, then turning to me, she added, ‘You should pick one up, too, Mish. A good hard massage will do you wonders.’

‘You know where you can get a good massage– Ah, here they are!’ Henry waved over my shoulder.

I turned and saw Matthew, stooping as always, a shy smile on his permanently flushed face, and for a moment I thought the promised son had failed to appear. But then the Vietnamese boy behind him stepped forward and raised a hand and I saw that he was too tall to be a local, his upper arms too thick. His smile showed teeth strong enough to bite through bone.

‘Everybody, this is Cal. Cal: Kerry, Henry, Amanda, Mischa.’

Cal nodded at us and we at him. Matthew looked relaxed, happy. I had expected shame, which I realise shames me, but there it is.

Henry started in on the kid: questions, recommendations, warnings. Kerry caught my eye, held up a cigarette and nodded toward the roof edge. While most of my Vietnamese friends found the sight of a woman smoking mildly scandalous, it was the norm amongst my expat pals. I think most of them smoked simply because they loved the idea of being able to do so in restaurants and on public transport. I understood that, and had no objection to others puffing away, but I mostly avoided it myself; even a slight shortness of breath felt like the onset of panic.

Kerry handed me a lit cigarette and I took it and held it over the edge of the roof.

‘Did you know he was Vietnamese?’ she asked.

‘He’s not. He’s Australian.’

Kerry flicked the air impatiently.

‘I didn’t know,’ I conceded. ‘But it’s hardly a surprise. There are loads of Vietnamese in Australia.’

‘It is a bloody surprise. I was expecting him to look at least slightly like his gangly, pasty-faced dad. Actually. . .’ Kerry frowned and drew back deeply. ‘Why didn’t we know what to expect? Why haven’t we ever seen a photo of the kid?’

‘We must have.’ I thought my way through each room of Matthew’s apartment. ‘I think there’s a photo album on the shelf next to his desk. I never thought to look through it.’

‘Weird that he doesn’t have photos of him scattered around the place though. I mean, that’s what parents do, isn’t it?’

‘Maybe it would make him sad to look at them every day.’

‘Or maybe,’ Kerry said, ‘he doesn’t want the women he brings back there to know he has a Vietnamese kid.’

‘Does Matthew bring women back there? I sort of assumed he-’

‘Ate out? Who knows?’ Kerry squinted at me through the smoke. ‘He doesn’t talk about sex, have you noticed? Not the way others do. The way we do.’

‘It’s just how he is.’ I ground my barely smoked cigarette out on the wall and tossed it to the street below. ‘It doesn’t mean anything.’

Back at the table Henry was in full flight, lecturing Cal about what he called ‘the tragedy of package tourism’. Amanda and Matthew, who had heard it all before, were huddled over the menu, bickering about whether to order tapas-style or individually.

‘Loo,’ said Kerry. ‘I’ll grab a jug of something fruity on my way back.’

Cal caught my eye and I smiled. I tried to see Matthew in him, but there was no trace.

When Henry paused to sip his beer, Cal said, ‘So, um, Mischa? I was planning on taking the Boobs and Booze Bus to China Beach, and then spend some time bumming around Dalat, smoking weed, but Henry reckons that’d be uncool, so now I’m at a bit of a loose end. What do you recommend?’

‘Had you really... Oh, ha. The famous Australian sense of humour, yes. I was only saying– ’

‘Do you like to walk?’ I asked.

Cal leant back and hooked his hands behind his head. ‘Hiking, you mean?’ He crinkled his nose towards his armpit and lowered his hands again, wrapping them around the sweating beer glass in front of him.

‘Oh, no, although there are some lovely national parks not too far out of the city. But I meant wandering. Walking around town, ducking down alleyways, getting lost in the Old Quarter. That’s what I recommend. To start with, anyway.’

‘Walking is a nice way to see the city,’ Henry agreed. ‘You need to take care in the heat, though.’

‘Come off it. I’m Australian, mate,’ Cal said, with an exaggerated drawl that reminded me of the men in khaki short-shorts in the outback-discovery documentaries I’d watched as a child.

‘Ah,’ Matthew said, passing the menu to Amanda, who waved it at the hovering waiter and told him to bring a mix of appetisers. ‘But heat here is a whole different beast. You really should avoid exerting yourself in the middle of the day.’

‘Yes. Watch the locals – they crawl into the shade and sleep through the hottest hour. The bloody tourists keep clambering around in their silly caps and thongs, turning brighter and brighter pink, shouting at vendors, getting their backpack straps tangled in the handlebars of parked-’

‘Henry doesn’t like tourists,’ Matthew told Cal.

‘Now that’s not true. Tourism means prosperity for this country. I respect that. But there was a time when visitors came because they were interested in the country and its people. They came with basic knowledge and a desire to immerse themselves in the culture, to learn more. But now. Now it’s become so cheap to travel here – especially, no offence intended, for Australians – that every idiot who manages to save a couple of hundred dollars from their weekend job at the supermarket turns up and starts haggling over thirty-cent cyclo rides.’

‘Ah,’ Cal said. ‘So it’s not tourists you dislike, just the working class.’

‘Oh, zing!’ Matthew held up a hand and Cal slapped it.

‘That’s unfair. Henry loves the working class,’ I said. ‘Who else would shine his shoes and cook his meals?’

Henry gave me what I’m sure he intended to be a disdainful look. He was criminally handsome, though, so it came off as smouldering. ‘I just don’t want Hanoi to become another Bangkok or Phuket. Is that so terribly snobbish of me?’

‘I’m with you, man,’ said Amanda. ‘I’m so over these sunburnt teenagers wandering around the Old Quarter with their tits spilling out of their tiny tops. Have some fucking respect!’

‘Sorry, where did you say these girls wander around?’ Cal asked.

‘Now seriously,’ Henry said, leaning in close. ‘If it’s girls you’re looking for, stay away from the potatoes.’

‘Potatoes?’

‘White girls,’ Kerry said, plonking a jug of something thick and green in front of me.

‘Not “white girls”. White girls who live on french fries and pepsi and slump around with their pasty potato flesh on display.’ Henry shuddered. ‘If you want to meet girls– ’

‘Enough. Jesus, this is my kid you’re talking to.’

‘Yes, yes. Right you are,’ Henry said, then in a theatrical whisper to Cal: ‘We’ll talk later.’

The food came. The three young Vietnamese waitresses bowed their heads and giggled as they placed every dish as close to Cal as possible. I saw us all through the serving staff’s eyes: five pale, wilting, thirty- and forty-somethings basking in the aura of this broad-shouldered, caramel-skinned, unwithered boy. They must have wondered where we found him and what we were going to do with him. I suppose they guessed that we would do what our kind always do when we see beautiful things that don’t belong to us.

Except he did belong to us, in a way. Anyway, he would be the first to say that he was one of us. He would insist on it.

My phone rang and I went to the edge of the roof to answer it. The number was unfamiliar and the caller hung up when I answered. The telephone numbering system had changed three times since I’d been in Hanoi and the printed directory was wrong as often as it was right. Still, such calls were unnerving. The easy party mood left me. I felt guilty, watched.

It had become dark without my noticing and the street below was as empty as it ever got. Six or seven motorbikes passed by, honking at the clear space in front of them. Across the street, a xe ôm driver rested on the back of his bike, his ankles crossed over the handlebars. Nearby, a grey-haired woman in yellow pyjamas squatted in the gutter scrubbing an aluminium pot.

‘Is she homeless?’

I jerked at the sound of Cal’s voice. ‘What?’ I followed his gaze to the old woman. ‘No, no. She’d live along this street somewhere. Probably behind that little green door there. People often wash-up outside. And cook and wash clothes and bathe children. Homes are so small, you see. And a lot of them don’t have what you’d consider a proper kitchen or they have to share one with others in the block.’

‘Do you have a kitchen?’

‘Yeah, I have to. My neighbours would die laughing if I came down and started chopping up veggies and boiling broth on the street.’

‘That’s why you have a kitchen? Because the locals would tease you if you didn’t?’ He had that flat, uniquely-teenaged tone that somehow suggested both outrage and indifference. ‘I suppose you’d have an outside squat dunny, too, if it wasn’t for the locals repressing you with their insistence on foreigners pissing inside.’

‘Ouch.’

‘I’m just saying.’ His gaze was still on the woman in yellow pyjamas. His long fingers tapped against each other and the muscles of his jaw popped and fell. The awareness that he knew I was watching him washed over me and I lifted my phone and pretended to be checking the screen.

‘I didn’t mean to offend you,’ he said after a minute. ‘I’m just a bit spun out by it all. People living like that– ’ he nodded towards the woman who was now standing and balancing the empty washing bowl on her head – ‘which I expected, because Vietnam’s poor and everything, but then Dad’s place is really nice. Twice the size of our flat back in Sydney. Ducted air-con and marble benchtops and all that.’ He squinted at me accusingly. ‘Do you have marble benchtops?’

‘No, but I wouldn’t feel bad about it if I did. I’ve done my time in rat-infested, four-storey walk-ups with death-trap spiral stair-cases and squat toilets. But then I realised how stupid it is to try to prove you belong by living like the locals – the least affluent of the locals, at that. As if choosing to go without hot running water could turn an American into a Vietnamese or a rich person into a poor one.’

He sighed. ‘I guess that’s true, but it doesn’t mean it’s right.’

‘Goodness, this has become terribly serious. We’re supposed to be celebrating your arrival. Matthew’s been so excited to have you here at last. How long are you staying?’

Cal stretched his arms over his head and made a show of inhaling the night air. ‘Don’t know yet. I’m meant to start uni in February. I’ve already put it off a year, but I might defer again. Stay here a while then travel around a bit.’

‘What are you going to study?’

‘Journalism.’

‘Like your dad.’

‘I guess. But that’s not why I’m doing it. I just really like writing and I like talking to people and finding out how life works, so I figured... Mum’s not keen on it, though. She kind of hates journalists. Thinks they use people. Take their most intimate stories and painful moments and turn them into breakfast-cereal placemats.’

‘Harsh.’

‘Oh.’ Cal half-smiled. ‘You’re not a journo are you?’

‘No. I work with lots of them, though. I edit a magazine. The kind that takes people’s stories and turns them into – well, not cereal placemats, probably more like bánh mì wrappers.’

‘Sorry. Anyway, I don’t agree, obviously. Some are scum, I know, but not all of them.’

‘Not your dad.’

Cal shrugged. ‘Wouldn’t know.’

‘You haven’t read his work?’

‘A little bit. His paper isn’t online and it’s not like his reports are syndicated or anything. You know, when I started planning for this trip, I decided I should study up, get some up-to-date info. I tried reading this book on modern-day Vietnam, but it was like a fucking economics textbook so I gave up. Then I set up a Google news alert, so I’d at least keep up with the big news stories out of here. But most days all the stories are about the US, not about Vietnam at all. “Iraq is not another Vietnam”, “Vietnam Vets protest pension cuts”. So I gave up on that, too. So here I am and I have no idea what’s going on.’

‘Oh, no one has any idea what’s going on here. It’s one of the attractions of the place.’

‘Oi!’ Kerry’s voice leapt out of the background hum of chatter and motorbikes and electricity. ‘Mischa! Come and back me up here. Henry’s talking absolute shit about visa extensions again.’

‘Duty calls,’ I said and Cal hooked his arm into mine and led me back to the table like it was his own.

***

Later, after I’d drunk far more than I’d intended, I found myself resting my head on Matthew’s shoulder as we shared the last cigarette in his pack. I was dizzy from the unfamiliar rush of nicotine, from the gin and beer, from Matthew’s unexpected fingertips on my lips as he held the cigarette there for me.

Across from us, Cal put down the plastic umbrella he’d been twirling and waved a finger from his father to me. ‘What’s this about? Something you need to tell me, Dad?’

‘What?’ Matthew smoothed my hair, bent and sloppily kissed my eyebrow. ‘Didn’t I mention that Mish is the love of my life?’

I blew smoke in his face. ‘Cal, it’s really quite remarkable the effect you have on your father. He’s like a new man. A new, fun, likeable man. I may fall in love with him after all.’

‘What do you mean may? You’ve loved me since you set eyes on me. Cal, did I tell you, the first time Mischa saw me she literally swooned? You’ve never seen a woman so delirious with desire.’

‘Oh!’ I sat up, knocking Matthew’s chin with the top of my head. ‘That’s right. The day we met...’ I slumped against him again. I had remembered something Matthew said on that day and I almost repeated it now, stopping myself when I saw that Cal was watching me.

‘That was a crazy day,’ I said and Matthew laughed and kissed my forehead again. ‘God, you really are marvellous tonight, Papa Matty.’

Cal made retching noises, then asked if he could order more food.

***

On my first day in Hanoi, six years ago now, jet-lagged, hungry and numb with shock, I’d wandered away from my hotel and got mindlessly lost in the ancient, winding, cacophonous streets of the Old Quarter. In a street lined with men carving tombstones I found myself breathing into a wall. I don’t know how long I stood like that, my forehead and palms against the cool, rough brick with the chiselling of stone and the roar of motorcycles and chatter of language swirling around me. It couldn’t have been long – as I quickly learnt, a tall white woman with dark red hair is never left alone for long in Hanoi – but it felt like hours. Even my memory of it is protracted; I feel I leant into that wall for at least as long as I had spent on all of the planes I had caught in the week leading up to it, from LA to Perth to Sydney to Bangkok to here.

Someone took my arm and led me into nearby cool dimness. Blur and noise and then I was sitting down and something cold and wet was pressed onto my face and then my neck and then my forehead. There was a drink in my hands and the chilled, sticky sweetness revived me enough that I had a moment of worry over the cleanliness of the ice clinking in the glass.

‘Thank you,’ I said to the girl blinking over me. She said something in Vietnamese and I was saved from not responding by the man I only then noticed sitting across from me. He was as pale as I was, although several days worth of stubble darkened the lower-half of his face. He answered the girl in what sounded to me like fluent Vietnamese and she giggled and scurried off.

‘Always making people laugh,’ he said in an Australian accent. ‘Even when I’m just asking for a bottle of water. How’re you feeling?’

‘Better,’ I said and drank some more liquid sugar. ‘Not used to the heat.’

‘How long you been in Vietnam?’

I couldn’t make sense of it. I knew I hadn’t spent a night in the hotel where I’d left my bags, hadn’t even eaten a meal. I knew the sun was as bright outside as it had been when I’d climbed into the Nội Bài airport cab. ‘Not long,’ I said finally. ‘A few hours.’

‘Ah. It can be overwhelming at first.’ He took the water bottle from the giggling waitress and passed it to me. ‘Hell, I’ve been here five years and I still get overwhelmed sometimes. How long you staying?’

I gave him the answer I’d given my sisters in Sydney. ‘I don’t know. It depends. If I like it I may never leave.’

‘Really?’

I shrugged as though it made no difference to me. ‘Do they have food here?’ I asked.

‘They do, but I wouldn’t recommend it. I was actually on my way to lunch when I saw you lurching about out there. If you’re right to walk, there’s a terrific phở stand around the corner.’

I went with him and didn’t feel too bad when he and the old woman behind the stove laughed at my clumsy attempts to scoop and slurp like a local. He told me his name was Matthew, that he was a journalist with the local English-language newspaper, that he lived in an apartment near the Opera House and that he would never leave Vietnam at all if it wasn’t for his son back in Australia.

‘His mother won’t let him visit me. She’s worried I’ll keep him here, I think. I visit him two or three times a year. Every time he seems to have grown half a foot. He’s twelve now and almost as tall as me. Lovely boy, though I’d never say that to him. He’s at that age, you know, wants to be a lot of things but lovely isn’t one of them.’

I’d never been interested in children, not even my nieces and nephews. I certainly couldn’t have interest in the unseen, unnamed child of a man I’d just met. Yet I remember Matthew speaking about him, remember the exact look in his dark, watery eyes. It’s not significant, I know that. It’s because it was my first day in Hanoi, because I’d swooned in the street and been revived by sugar water and beef noodle soup and now everything was sharp and vivid and searing. I remember the nostril-stinging steam from the pot of broth on the stove, the twinge in my lower back and ache in my thighs as I perched on the child-sized plastic stool, the extraordinarily constant tooting of horns. I remember Matthew’s khaki lizard-print shirt and tan linen trousers, the way the wiry black hairs on his forearms glistened with sweat. I remember the barefoot toddler chasing a gecko across the concrete floor and his mother, fanning herself in the furthest corner of the room and smiling every time his body crashed into our plastic table. And I remember that Matthew told me he had a son who was twelve and lovely.

After lunch, Matthew had walked me to my hotel, which was, incredibly, one street back from where we’d eaten. ‘Everything’s close here, as long as you know where you’re going. Two blocks that way,’ he said, pointing, ‘is Hoàn Kiếm Lake. Nice place to sit when it all feels a bit too much.’

‘Thank you.’

His sweat dripped in two almost straight lines from each temple, but he seemed not to notice. ‘If you’re up to it, a bunch of us are going to the bar at the Metropole tomorrow night. It’s the priciest bar in the city and full of wankers, but it’s, uh, it’s my birthday actually, so. . . Well, we’ll be there pretending to be rich and oblivious. You might enjoy it.’

‘Okay,’ I said, having no idea what or where the Metropole was and no real intention of finding out by tomorrow night.

‘Tell you what,’ Matthew said, retrieving a set of keys from his pocket and jiggling them. ‘Since you’ll still be finding your way around, I’ll come by and pick you up. Seven-thirty?’

‘Okay,’ I said again and Matthew smiled and turned and seemed to melt into the crowd.

I nodded to the smiling man at the desk and climbed the four flights of stairs to my room where I stripped off my sweat-soaked clothing and laid myself out to dry under the slow ceiling fan. I wondered what Glen was doing, who he was taking his rage out on now.

***

The following night, Matthew picked me up on his motorcycle which he drove like a local, weaving in and out of the traffic, ignoring lights and lines, missing other vehicles and pedestrians by millimetres. By the time we arrived at the Metropole I was shaking.

‘You’ll get used to it,’ he said. ‘It looks crazy but it’s actually very safe. Everybody’s paying close attention, not relying on other people obeying rules.’

Later I’d discover that thousands of people die on these roads every year. Later I’d see a woman flip over the handlebars at an intersection and have her head smash open like a watermelon. But that evening I clung to Matthew’s assurances and to the casualness with which everybody I met there talked about driving through the city. It can’t be that bad, I thought, if all of these clever, sensible people are okay with it.

Of course, most of them weren’t clever and none of them was sensible, but it took me a while to figure that out. Everybody I spoke to that night had a convincing explanation for what they were doing there and I left thinking that I had stumbled upon a community of laid-back, self-deprecating saints. Genuine doers-of-good who still enjoyed a drink and a laugh. I assumed they were all so welcoming to the frazzled, explanation-less stranger out of pity and kindness. To be fair, there was a bit of that. But mostly they were so warm because they recognised me as one of them: a damaged fuck-up unable to thrive in her own land.

I’m not saying all the foreigners in Vietnam are like that. Some of them are genuine and kind and altruistic. Some of them have a deep love for the Vietnamese culture and language and landscape. Some of them are kick-arse corporate whizzes doing their multi-national expansionist thing before jetting off to the next new boom-town. But the people at Matthew’s birthday party, the people who would become my social world, were in Hanoi because it was the only place they’d found where they could get away with being who they were. The only such place with five-star hotel bars, anyway.

***

Six years later, the Koto get-together ended like so many others before it. The restaurant closed and we all bundled onto xe ôms or into taxis and waving and shouting we went our separate ways. The night sticks in my mind, though, not because it was the first time I met Cal, but because it was the first time I’d known Matthew to be happy. Not that I’d thought of him as unhappy before then. Happiness is relative, surely, and for those first years of my friendship with Matthew I had nothing to compare his to. He could say the same about me, which must make it worse for him.

That gathering sticks in my mind – in my conscience – because I laid my head on Matthew’s shoulder and felt him revivified by Cal’s presence. I wonder if he looks back and remembers a similar change in me not long afterwards. I wonder if he remembers me coming to life and now that he knows why he wishes I had stayed dead.

II

Over those six years in Hanoi, I had five addresses not counting the hotel I stayed in when I arrived. My last house, tucked down the back of a courtyard at the end of an alleyway behind the cathedral, had hot water and air-conditioning but neither could be guaranteed on any given day. The kitchen was a sink and stove-top in one corner of the living area. The fridge hummed loudly next to my TV. There was a rosy-tiled bathroom with a temperamental shower and an upright toilet which needed unblocking every month or so.

And there was the reason I loved it enough to put up with everything else: a bedroom that covered the entire second floor, with windows as tall as me on two sides. They were double-glazed but could not silence the bells of St Joseph and the constant rumble of the traffic. I often spent whole weekends in bed, eating honeyed cashews out of a cellophane bag and reading paperbacks from the English-language book exchange.

When I was married I fantasised about this kind of aloneness. I spent a lot of time physically alone back then, but I was accountable for that time and could get away with only a very small amount of reading or TV watching. An entire day spent in bed would have been unforgivably self-indulgent. Even when Glen was on one of his trips, I would need to report my activities hour by hour. For a long time it didn’t occur to me to lie, and then when it did, I quickly discovered what the consequences for being caught in a lie were, and so reserved my deceit for covering up essentials like phone calls from my sisters.

In my Hanoi bedroom, with the ever-present background hum of three million people and the knowledge that my landlady, all of my neighbours, the local Communist Party rep and probably the police were keeping track of my every move, I felt truly alone. Free and safe from judgement.

It didn’t last. I suppose I began to take the benign interest for granted and flaunted my freedom, inviting suspicion and scrutiny. I never discovered exactly what my neighbours knew or how they knew it, only that they had turned against me. Scorn and disgust are among those emotions easily expressed without language.

***

Three days after Cal arrived in Hanoi, Matthew organised a picnic lunch in Quốc Tử Giám Park. It was a Saturday and by the time we arrived, all the gazebos had been claimed. We managed to score a patch of grass on one side of a banyan, so we had some shade at least.

Henry had brought along a workmate, a New Zealander in his early forties who wore a white linen suit and introduced himself as Collins.

‘Colin, is it?’ said Kerry, sliding her sunglasses down her nose.

‘Collins,’ he said, emphasising the s.

‘Collins just arrived from Kuala Lumpur last week,’ said Henry.

‘Promoted to Hanoi,’ Collins said. ‘How’s that for an oxymoronic phrase?’

‘How’s that for a moronic suit,’ Cal, who was sitting to my left, reading a yellowing paperback, murmured.

‘Promoted from what to what?’ Matthew asked, unloading a basket of mini-baguettes from his Fostersbeer cooler.

‘Head of IT in a small, modern, professional office to Head of IT in a wastefully large, colonial office staffed by people who think networking has something to do with fish.’

‘Sounds like they’re lucky to have you,’ I said.

‘What?’

‘Oh, they are,’ Henry said. ‘We all are. That department’s useless. I could get better tech support from my housekeeper.’

‘Ah, but your housekeeper is the amazing Giang and there’s nothing she can’t do,’ said Kerry.

‘You have an actual housekeeper?’ Cal asked.

‘So do we, kiddo. Who do you think has been cleaning the place and stocking the kitchen before you get out of bed each morn– each midday?’

Cal blinked. ‘You?’

‘He’s only been here a few days,’ Henry explained to Collins.

Collins squeezed into the space between Cal and Kerry, put a pink hand on Cal’s shoulder. ‘Something you learn quickly in Asia. The value of a good housekeeper.’

Cal turned to his father. ‘So everyone here has a housekeeper?’

‘Pretty much,’ Matthew said.

Cal nodded towards an old man swinging his arms and legs in tai chi motion. ‘So he’d have one?’ He pointed to a woman dressed in a green canvas apron, picking up rubbish with black-gloved hands. ‘And her?’

‘Well, no, but you know I didn’t mean that.’

‘You said everyone.’

Matthew sighed. ‘Yes, I did. I meant all of us here. We foreigners.’

‘I was determined not to, at first,’ Kerry said. ‘My posting before this was in Malawi and I managed to do everything for myself there. But here it really is very difficult. Buying food at the markets, organising repairs or deliveries, even garbage pick-ups – if you’ve got white skin and not much Vietnamese it’s tricky and expensive. Having a housekeeper, if you find a good one, is like having a personal assistant. Not so much about cleaning as about day-to-day life stuff. I can scrub my own toilet, but hell if I can figure out how to get my air-conditioner re-gassed.’

‘Speak for yourself,’ said Collins. ‘For me, the best part about these postings is not having to clean anything except my own body.’

‘Oh, I can recommend a service to do that for you too,’ Henry said and he and Collins clicked together their empty plastic glasses.

While Kerry mixed up a jug of iced lemon tea and Henry, Matthew and Collins discussed the Euro zone debt crisis, I cut open the baguettes and filled them with the slivers of pork I’d roasted and sliced that morning and handfuls of shredded coriander and basil from Matthew’s roof garden. Cal squatted beside me, watching.

‘Your servant got the day off?’

‘Of course not. She’s back home polishing the silver and hand-washing my underwear.’

He smiled. ‘What’s this then – bánh mì?’

‘Ah, well, it’s inspired by bánh mì, but since I wouldn’t want to give bánh mì a bad name, I call it what it is, which is pork and herbs on a bread roll.’

‘Fancy.’

‘No. But very delicious. Here.’ I handed him a roll and he bit into it. Flakes of golden breadcrust fluttered to his lap. In four bites it was gone and his mouth was slicked with grease. He gave me a thumbs-up sign and licked his lips.