Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Merlin Unwin Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

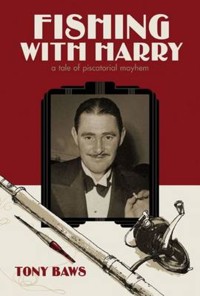

Harry, an incorrigible, engaging and dapper biscuit salesman in his forties, ex-Army and the City, becomes the unlikely angling companion of young Tony, the love-struck, shy 19-year-old accountant who is courting his step-daughter. Throughout the 1960s, this unique fishing friendship is cemented via a series of largely nocturnal fishing jaunts across London, Essex then further afield, to ponds, gravel pits and rivers. As mods and rockers hit the scene, Harry and Tony set off at first on buses, then on a scooter and later, more luxuriously, in Tony's battered green Ford. With huge excitement and more than their share of mayhem and mishap, they cast their lines wherever fish are to be found (or not, as the case may be!) At times touching, at times bawdy, always amusing – this is a book not just for anglers but for anyone who enjoys a finely-told story. ** All royalties from sales of this book will be donated to the charity CRY (Cardiac Risk in the Young) **

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 457

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to the beautiful life and memory of Gideon Baws

Contents

A Word of Thanks

Each week, in the UK alone, some 12 young people between the ages of 14 and 35, apparently fit and healthy, die suddenly of an unsuspected heart condition, leaving their loved ones and friends bewildered and devastated. One such loss among that staggering number is our darling son Gideon, at the age of 33.

Gideon was hugely talented, loving and lovable. He was fond of swimming, cycling and walking – in the May before he died he had swum 5 kilometres with a good friend to raise money for the Marie Curie cancer nurse charity. There was no history of heart problems. He was an entertaining drinker and a sensible eater, he was not overweight and he never smoked (beyond the usual college experiments!)

The charity CRY (Cardiac Risk in the Young) fulfils many important functions: it offers comfort and counselling to bereaved families; it acts to raise awareness by lobbying parliament and promoting an all-party group to keep these tragic deaths in the forefront of the minds of government. It sponsors clinical research through its dedicated units at the Royal Brompton Hospital and St. George’s Hospital, Tooting.

CRY also supports cardiology screenings for the age group most affected. Arranged either nationally or by individual fund-raisers, staffed by medical experts in this highly specialised field, using equipment provided by CRY, the hope is to identify at an early stage those at risk and to advise them accordingly.

Author royalties from the sale of this book are committed to CRY; to raise money for their essential screening projects and to contribute towards their core funding. Thank you so much for buying it.

Tony and Suzie Baws September 2011

CHAPTER 1

Wake up, little Suzie

‘This above all: to thine own self be true And it must follow, as the night the day, Thou canst not then be false to any man.’

SHAKESPEAREHamlet

The little I saw of Harry in the early days of my courtship of his stepdaughter was mostly his rear view: a broad back in a striped shirt, trousers riding high on elasticated braces. His hair was black, cut severely in a short-back-and-sides, parted in the middle and given an oily gloss by the liberal application of hair-dressing. Occasionally I could detect the merest hint of soap by an ear, which only served to amplify the overall impression that he was scrubbed clean to within an inch of his life.

This imposing figure was not much given to small talk. Some people found Harry threatening and I understood why he had this effect. I did feel some awe, but what I mainly felt was amusement.

I soon came to know Harry’s routine. Every afternoon, as soon as he returned from his daily sales round in London, he commenced his paperwork. He put a lot of physical effort into his paperwork, did Harry. First a rickety, two-tiered wooden trolley, his mobile office of the day, was wheeled ceremoniously into its allotted position under the ceiling light, next to the oak gateleg table in the living room. On the top tier of the trolley were white customer record cards, yellow-pink-blue triplicate order forms and buff envelopes. In one corner sat a small, round tobacco tin, delicately decorated in brown on a yellow background, depicting female peasant-farmers in far-off lands, chatting and smoking as their crop was loaded onto mule-drawn carts. This charming container bore the evocative brand name ‘The Balkan Sobranie’. It now held postage stamps.

A rubber band secured the bundle of customer records, and under this Harry had jammed a collection of pencil stubs, none longer than three inches. Alongside these sat a worn, grey eraser – a rubber sexton in a pencil graveyard. On the lower trolley shelf were piles of unused record cards and sheets of blue carbon paper. A battered leather briefcase with a frayed handle was placed, just so, next to the trolley. Harry pulled his chair up to the table. He was ready to begin.

In a practised blur, his hand disappeared into the briefcase and reappeared holding papers. These he smacked down onto the table. A pencil-corpse was selected from the assorted cadavers. Figures of quantity and price were transposed from the briefcase papers to the trolley-borne cards. The stubby pencil pressed down so hard that the table vibrated. Harry’s knees shook, his feet tapped furiously and he emitted a high-pitched keening noise as he concentrated on his work. Every so often he would reassure himself with a few words of encouragement: ‘That’s that!’ he would say out loud, ‘that’s that!’

Harry’s regular steam train home from work was known locally as ‘The Four O’clock Express’ and it ran non-stop in 45 minutes from London to Leigh-on-Sea. A short haul down the line, past the cockle sheds and round the bay was Chalkwell Station. Here Harry would stir himself and get ready to alight. Sometimes, after celebrating a particularly large order, he might imbibe too freely of draught Guinness in the London station pub before the train departed. Snug in the warmth of the carriage, he would occasionally fail to notice his arrival at Leigh, or Chalkwell, or even Southend, but instead travel to the end of the line at Shoeburyness, there to be awakened in a befuddled state by a member of railway staff checking the train before it was shunted onto the up line for the return journey.

As our courtship progressed, I became a frequent visitor to Harry’s house. ‘Evening, Mr P.,’ I would offer in friendly greeting, feeling that a formal mode of address was appropriate. I was only just restrained by Suzie from calling him ‘Sir’. (By the time we went fishing together it was Harry or H. I never called him by his surname, whereas he would often call me by mine. I accepted this as a mark of affection even though it revived painful memories of school, where the use of a surname, bellowed by a master, would inevitably be followed by punishment, usually of the corporal variety).

‘Hmmmm … Tony…’ he would reply distractedly. It was the only acknowledgment of my presence that I would receive until he had finished his task. Eventually, the completed orders for Head Office were thrust into their envelope. A pen was grasped, an address scribbled, and the envelope glue licked extravagantly. A postage stamp was equally lavishly licked and pounded into place. His wife, Billie, would scurry off to the pillar box clutching the precious envelope. The day’s work was done. Only then would Harry turn to face me, smiling, with eyebrows raised, and offer me his standard greeting to all and sundry men: ‘How are you, boy?’

Harry’s father, Henry, died in the First World War. En route from Marseilles to Egypt on New Years Day 1917 his troopship, the S/S Ivernia, was sunk by a German U-Boat off Cape Matalan in Greece. An almighty explosion wrecked the engine room and steering, leaving the ship floundering. A destroyer from the convoy came alongside to assist, but high seas, whipped up by a ferocious winter gale, smashed the two ships together. In the confusion many lives were lost. His body was never found.

Harry, born two years earlier and christened Henry after his father and his father before him, was raised by his mother. She would have preferred a daughter, and dressed Harry accordingly. Nevertheless, she always referred to Harry as ‘Boy’, to others and to his face, a nickname she used even when he was grown up.

Photographs of Harry as a baby and as a toddler indeed reveal a winsome child of uncertain gender. Clothes of the period were at any rate full of fandanglements and lacy embellishments. So keen was his mother to protect Boy’s pristine condition that she continually washed every reachable surface in their home, fearful that her inquisitive offspring might touch something dirty and besmirch himself. According to family lore, the cleaning regime extended to the coal as well as the coal scuttle.

This fastidious upbringing no doubt contributed to Harry’s adult preoccupation with the detailed maintenance of his person. Some might describe his rigorous washing and the subsequent application of cosmetics, humectants and unguents to various parts of his body and face as mildly obsessive. Other, less tolerant, observers of these ablutionary and decorative rituals called it a perversion.

Harry was privately educated and began his working life, courtesy of a family connection, at the Public Records Office at Kew, by the Thames in Surrey. There he acquired an interest in history and geography, subjects in which he had not shone at school, where, he confessed, he ‘buggered about, went on the piss a lot, and achieved fuck all!’ The post included a period of secondment to the American Library of Congress. The work was interesting and responsible, with a certain cachet, but poorly paid. He considered in later years that maybe he had been foolish to leave that privileged position, but, like many young men, he was envious of the salaries his friends were earning in their less demanding careers. Harry followed the money and chose a job selling insurance. Hertfordshire was his territory and he counted among his clients the barge families who traded along the Grand Union Canal, going aboard to collect premiums whenever the boats stopped over at Rickmansworth or Kings Langley. He enjoyed the time spent in the open air and the relaxed nature of his few appointments. ‘Self determination, Baws,’ he would frequently tell me, ‘that’s the key.’ The Prudential continued to pay him even after he enlisted in the Army at the outbreak of the Second World War.

At the time I met him, Harry was a high-class salesman of high-class biscuits. His customers included Harrods, Fortnum and Mason and the Army Officers’ messes in Chelsea and Kensington. Harry the Salesman played the part of the complete city gentleman: smart dark suit and overcoat, regimental tie, bowler hat, impeccably rolled umbrella and extraordinarily shiny shoes. He polished his shoes and cleaned his bowler hat with the same energy and vigour that he applied to his paperwork, but in place of a stubby pencil on paper, he wielded stiff brushes to attack his clothing. He did this so effectively that he eventually wore away the nap on one side of his best rabbit-fur bowler hat.

He caught the train from Chalkwell to Fenchurch Street in London at 6am Monday to Friday. This regime obliged him to rise at 3.30am, in order to give himself time to wash, pamper and preen to his satisfaction and still leave time to walk to the station, which he did in all weathers.

On the dresser in his small bedroom, Harry kept a large wooden tray which he used as a portable bathroom cabinet, containing a panoply of personal hygiene and cosmetic potions, lotions and equipment. Neatly arranged on the tray were a circular shaving mirror on a stand, a pair of tweezers with flat ends, an eyebrow pencil, his toothbrush, a flannel in a plastic dish, a tube of Kolynos toothpaste, a tin of Gibb’s dentifrice, a deodorant stick, a bar of soap in another plastic dish, a tin of talcum powder, some cotton wool, a jar of Morgan’s pomade and various brands of aftershave: Yardley’s, ‘Old Spice’, ‘Pasanda’ and ‘Cedar Wood’.

Then there were several bottles containing Bay Rum, Hungary Water and Eau de Cologne. Some of the packaging was exotic. My favourite was a bottle of Eau de Cologne, apparently made in England but bearing on the reverse of the label a mine of oddly translated information, both exhortative and cautionary, liberally sprinkled with asterisks:

* Invented about 1750 AD. A most refreshing toilet requisite

* Healthy * Hygenic [sic] * Used for after-shave * Hairfriction

* When having a cold, dampen your handkerchief

* Clean your face to take the make-up

* Few drops whilst cleaning your underwear

* Sprinkle sick-rooms or general cleaning

* But avoid polished furniture-tops

* A hundred uses feeling fresh – invigorating when using.

The main constituent of this Eau de Cologne was de-natured alcohol, contrived to dissuade the drunk, the unwary and the misguided from consuming it. De-natured or not, Harry, by his own admission was signally undeterred. At one particularly riotous Christmas party, held at a grand house in Tring, (the residence of a most important client), he had consumed half a bottle of this stuff, for a bet. Already drunk on ‘Green Goddess’ – a proprietary liqueur with a crème-de-menthe base, popular at the time – and feeling, as he put it, ‘rather poorly and confused’, he had sought escape and refuge. The Yule log mercifully unlit, his unfocused eyes mistook the magnificent walk-in fireplace in the entrance hall for the cloakroom. Finding his exit barred, he attempted to climb the chimney, in the reverse fashion of Santa Claus. Exhausted in time by these efforts, he eventually collapsed in the grate. There he was found come the morning, suffering from an atrocious hangover and covered in soot.

Completing the collection on Harry’s tray was a tube of Lavender Hair & Body Wash, a badger-bristle shaving brush, a tube of ‘Old Spice’ shaving cream, a Gillette safety razor, a packet of ‘7 O’clock’ razor blades, a styptic pencil, some orange cuticle sticks, a nail file, a nail brush, a bottle of ‘Man Tan’ instant tanning lotion, a bottle of brilliantine, a tub of Brylcreem hair dressing, a bottle of Silvercrin hair tonic, a tortoiseshell comb and two silver-backed hairbrushes.

Every morning Harry carried this tray of preparations to a small table in the tiny kitchen of their flat above the tropical fish shop. There was no bathroom on the top floor where Billie and Harry lived, and he declined to use the one in the lower area of the flat occupied by his mother-in-law. There was a toilet, but even that involved a trip outside to a small, detached building on a roof terrace, accessible by a door from their cramped sitting room. The only heating in winter came from an open fire and a paraffin heater. There was no running hot water. He put two kettles on the gas stove and lit the rings. Placing a towel on the floor beneath the kitchen sink and warmed only by the paraffin heater, he stood on the towel and undertook his ritual cleansing and make-up for the next two hours, starting with a stripped-down-head-to-toe wash.

Liberally applied, the ‘Man Tan’ lotion imparted a somewhat orange shade, which contrasted sharply with the glossy black hair, black-pencilled, plucked eyebrows and trimmed moustache, giving him a strikingly theatrical appearance. Harry always maintained that a salesman’s role was basically an act, but sometimes, when he had overdone the cosmetics, he looked more like a pantomime ‘Baron Hardup’ than the Errol Flynn look-alike to which he surely aspired. A final splash of aftershave, another dab of Eau de Cologne and Harry was ready to face the day.

If questions were ever raised about the time he spent at his washing and beautification, Harry could become agitated.

‘You go to France or Germany, or anywhere in Europe,’ he would respond, ‘men there naturally take care of themselves, think nothing of it. It’s only the Brits that are such filthy people, Baws,’ he would rage. ‘Look at them throughout history. We were wearing woad and animal skins when the Egyptians were already civilised. Elizabethans, Jacobites, Stuarts, Cromwell’s lot, Reformation – they were all foul sods. Never washed, just covered everything up with powder and perfume. Fold them over and their pants would crack!’

Every Sunday without exception, Harry dressed in military fashion: khaki trousers, khaki shirt, khaki socks, brown shoes and a thin green woollen tie.

‘I don’t bother to ponce up on a Sunday, Baws,’ he once explained. ‘Of course, I still have a full wash down.’

It wasn’t hard for me to fall in love with Suzie. Incredibly beautiful, with long black hair, green eyes, slim and delicate, she was intelligent, warm-hearted, talented and funny. And to cap it all, her name was a hit record by the Everly Brothers, one of my favourites. What she saw in me I will never know. She had a penchant for swarthy East European Gypsy musicians à la Django Reinhardt, and American tough guys Humphrey Bogart and Burt Lancaster (though she also swooned over a handsome blond-haired actor in some God-awful black-and-white Czech film – ‘Ashes and Diamonds’). Maybe a dark, young, bespectacled, Jewish trainee accountant from Westcliff was just what she needed to satisfy her exotic taste until the real thing came along.

We had no sooner plighted our troth than Suzie was rushed into hospital with appendicitis. Visits were short, and Suzie was asleep for a lot of the time. Anxious for news of her progress, I spent an increasing amount of time at her parents’ flat.

Suzie came home from hospital and our courtship blossomed. After her initial fright upon meeting the blonde, five foot nothing, impeccably attired, fierce woman that was my mother, the two bonded closely. Since we lived only a few roads apart, we spent a lot of time in each others’ homes. Differences in our families and cultural upbringing were never a source of friction. True, Suzie’s mum, Billie, (also five foot nothing), spoke in a refined voice and hated swearing, whereas my mother Lily, while well-spoken, could and did eff and blind with some fluency and to considerable effect.

Nor were religious differences an issue. Harry’s first wife had reportedly been Jewish, although he rarely talked about her. Phyllis suffered terribly from depression and her condition worsened after the birth of their only child in 1946. Harry was forced to abandon a successful career at the War Office in order to care for her. Despite his best efforts and his frantic rescues of Phyllis after her several failed attempts, she eventually succeeded in committing suicide.

Unable to look after his one-year-old son by himself, Harry gave him into the care of close relatives. It was accepted that he would always recognise David as his son, but all agreed it would be best to keep contact between them to a minimum. By the time I met Suzie, Harry had not seen David for many years.

It seems that Harry was no stranger to alcohol in his younger years; on the contrary, episodes like the Christmas at Tring were fairly commonplace, (though he had learned his lesson with Eau de Cologne). The consumption of alcoholic drink might indeed have ranked as one of his major pastimes, both as a civilian and in the army. This compared sharply with me, who felt reckless drinking half a pint.

Often he regaled me with tales of mess-room drinking games, all of which demanded the ingestion of copious amounts of ale. One such was ‘Cardinal Puff’. As far as I could tell, this involved reciting some mumbo-jumbo, downing beer and performing an arcane series of tapping movements with one’s fingers in the correct order, all the while being closely observed by one’s peers. If the strict rules of the game were not followed to the letter, the glass was replenished and the increasingly befuddled participant had to start all over again. Since prospects of eventual success diminished with each failed attempt, much drunkenness ensued.

By the time he met Suzie’s mum, Harry was also drinking to obliterate the memory of Phyllis’s tragic death. Billie was herself recovering from the trauma of a failed marriage to Suzie’s father and living at the time in what she hoped would be only temporary accommodation with her young daughter. It happened to be close to where Harry’s mother lived, leading to a chance meeting. Perhaps Billie’s strait-laced attitude and teetotal lifestyle were the soothing balm, the antidote and the sanctuary that Harry desperately needed at the time. When questioned on this, Harry for his part, while expressing gratitude for her intervention, always maintained that ‘Billie’s big bosoms were the clincher’.

Harry and I gradually became more relaxed in each other’s company, although conversation was still limited. Until one day he said to me, completely out of the blue, ‘Ever go fishing when you were young, Tony?’

‘Yes,’ I replied slowly, ‘I used to go quite a bit when I lived in Benfleet. Why?’

‘Oh, just wondered.’

‘I never caught anything of any size, Mr P. – Harry. Just tiddlers really. Used to take them back in a tin and put them in the pond in the back garden. What about you?’

‘There used to be a place over by Lime Avenue, off the London Road in Leigh,’ said Harry. ‘Brush’s Brickfields – it was called. Stacks of roach in there.’

‘That’s where they built Belfairs School isn’t it?’ I knew it well. ‘I never went fishing there,’ I told him, ‘but I used to play football in the field the other side of the sand pits. All built on now, I suppose.’

We sank back into silence. Had someone interrupted us at that moment, had there been a knock at the front door, maybe both our lives would have been the poorer. Instead, Harry started up once more.

‘Ever thought about going again?’

No, I hadn’t. I went over the prospect in my mind. I liked the outdoors. I played rugby, football, cricket. I was even press-ganged into running cross-country for my school. The course followed the shores of a large lake which held huge carp. Spotting the basking fish on my way round took my mind off the boredom and cruelty of cross-country running. But I hadn’t fished for years. I had no tackle, no appropriate clothing, and up to that point, no interest in fishing at all. The suggestion was crazy, but crazy ideas I liked.

‘Why? Were you thinking of going, Harry?’

‘Well, only if you fancy it, Tony,’ he replied. Hang on I thought, I didn’t start this. I should have bailed out at that point. But I ploughed on.

‘Have you got anywhere in mind?’

‘I was talking to old dog-face the other day. You know, whassisname, Old Clarke. Comes round with the shellfish cart on Fridays. He says there are huge carp in Priory Park but no one ever catches them. He reckons you’d have to fish at night to stand any chance.’

‘We could go down and have a look on Saturday morning if you like,’ I said cheerfully. Best not tell him at this stage that I had never fished at night in my life. I imagined from the confident way he spoke that he would be the one with some experience, the expedition leader. Oh, how wrong I was.

CHAPTER 2

The Priory

‘Footsteps coming down the stairs! Who should it be but the maiden’s father With two pistols in his hand, Looking for the man who shagged his daughter! Jig-a-jig-jig, jig-a-jig-jig Balls an’ all – jig-a-jig-jig très bon!’

In the distance I could hear Harry’s strange song, sung purposefully to his marching footsteps. He never would say where the song came from. Maybe army days, maybe drinking days in Ireland. Whenever I asked, he just grinned and carried on singing:

‘It… suddenly came upon my mind

To shag Old Reilly’s daughter …’

Billie was not in favour of swearing. ‘Harry, please!’ she would scold, whenever Harry voiced what was for him a mildly rude word. He did it to annoy her, and giggled like a naughty boy. Billie had been brought up in the Anglican Church and she never failed to reprimand Harry for his swearing and blasphemous outbursts. This only made him do it all the more, drawing from her ever greater reproach, much to his amusement. I wasn’t particularly foul-mouthed or blasphemous until I met Harry. Somehow we sparked off each other. When fishing was quiet we often made up obscene limericks or spoonerisms or just streams of blank verse swearwords, seeing who could make up the longest unbroken chain.

The singing changed to a loud humming and the footsteps drew closer. I edged out of the door into a warm and gentle May night. Silent, except for Harry. I could make out his beaming face in the half-shadow of the street lights down on the main road.

‘Is that you, Tony?’

‘No – it’s the Archbishop of bleedin’ Canterbury, you daft sod!’

‘Hello Baws. Smashing night. You going to float fish?’

‘Probably.’

‘Flake?’

‘Yes.’

‘Got some bread?’

‘YES! Come on………….’

It soon got to be like that with Harry. He would ask question upon question. I would become short tempered very quickly and he would stop for a while, but soon start up again. ‘Looking forward to it, Baws?’ asked Harry. From that vague discussion some months ago of how we had gone fishing in our childhood, we had now worked ourselves into a state of extreme excitement and anticipation. From the moment we had decided to go fishing we had talked of nothing else, thought of nothing else. The fishing drug was in our blood, and it was to stay that way forever.

There was no one else around, which was just as well. We were a strange and lawless-looking pair. Harry, who during the week was immaculate in pinstripe suit and bowler hat, was wearing for this occasion old corduroy trousers, tucked into wellington boots and done up round the waist with a long woollen scarf. Over a purple jumper he sported an ex-army leather jerkin, and on his head was a knitted army hat, with a pheasant feather stuck in it at a jaunty angle. His application of tanning lotion imparted a particularly stage-like appearance under the street lights.

I was still in my Buddy Holly phase, all thick rimmed glasses and dark suit. But for fishing I had acquired a camouflage outfit from the local Army & Navy surplus store, and so with the rod bags over our shoulders and in the dim light we looked like mercenaries in search of a war.

Prittle Brook in Essex runs down from Daws Heath, through Hadleigh Great Wood and Belfairs Wood and on to Rochford where it joins the River Roach. Leaving the north part of Southend it passes through Prittlewell. Here in the early 12th century, Robert de Essex gave a grant of land for the establishment of a Cluniac Priory. This survived with various alterations and additions until 1536, when, during the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII, the buildings fell into disuse. Importantly for us, however, the monks had established fish ponds for their carp stocks, and incredibly these ponds still remained.

At Prittlewell, the brook is culverted under the road before emerging into the park – ‘The Priory’. Close to the ruins of the monastery are the two ponds, divided by a strip of land about four yards wide, accessible from one end (but still referred to as ‘the island’). These were nominally club waters but, being a Corporation property, day tickets were available to the public, and the area was jointly patrolled by club bailiffs and corporation ‘parkies’. But there was definitely no night fishing, and fishing out of season was not even considered. Doing the two together was probably a hanging offence.

We shinned down the banking before the concrete culvert began. I was just 20 years old. Harry was 45 and fairly fit, in spite of the disdain he always expressed on the matter of physical pursuits. However inept he made himself out to be, some of his reluctantly acquired military training must have stuck.

Bending nearly double, we crept under the long road bridge, trying not to step into the shallow brook. Once in the park, we kept in the brook cutting until we felt far enough away from the street lighting. Up onto the bank, we walked silently along the grass edging to the dog-leg fence which protected the edge of the first of the two ponds. We paused at the fence, listening for any human noise. No clicks or rustles, no hiss of line on reel. No lights.

‘What do you reckon, Tony?’ whispered Harry. It was the first time either of us had spoken since we entered the park.

‘Let’s make our way onto the island,’ I whispered back.

The island seemed to be more overgrown than I remembered it from the single daytime recce. The rods and the tackle, not to mention Harry, did not make things easier. Five paces forward and I was stuck. We shuffled back the way we had come.

‘Look, you wait here, Harry, and I’ll go and check the swims.’

My eyes were now accustomed to the dark, and by a slightly different route I came out to a fishable swim about half way along the island. Alongside, separated by an overhanging hawthorn bush, was a spot for Harry. That became the way of it over the years. I would lead the way, find two adjacent swims, mine and Harry’s. He was always so good about it, never complained when I had first choice and took the more promising place. We always fished side by side, only as far from one another as a stage whisper would carry in the silence over the water. I went back for Harry and cautiously we threaded our way through the overgrowth to the two swims.

There was not much headroom to tackle up, but we both had only two-section rods and centre-pin reels. I had mastered one single knot because it was easy to tie in the dark. With the rod silhouetted against the night sky I threaded the line and tied the hook. I had the choice of two floats, both of them the kind that boys used to buy. Bright and bulbous, they took about an ounce of lead to cock them. I put one up the line and went round to give the other to Harry.

‘This one be all right, H?’ I showed him the float in the light of the torch.

‘No, it’s okay, Tone. I’ll just sit and watch you. Feeling a bit gutty.’ Poor Harry. Fit as a flea really, but he was obsessed with the minute-to-minute condition of his bowels and his snout. The first he put down to a bad case of dysentery when he was in the army. Fair enough, but I felt that the situation was not helped by his huge appetite.

Billie, long-suffering soul, had prepared for us two identical boxes of food to take on this, our first fishing trip; hard boiled eggs, sandwiches, biscuits, fruit, and so on. Foolishly, I had left both boxes in Harry’s care.

‘Harry – where’s my food?’

‘Don’t know, Baws. Isn’t it there?’ Greedy sod. ‘No Harry, it’s not effin well there. Have you scoffed it?’

‘I haven’t had it, Tone.’

‘Well, there’s none left.’

‘Oh. Well, I only ate mine!’

It was useless to argue with him. He ate like an automaton. Or a bison. He had grazed away until it was all gone, mine included. As to his snout, as Harry often remarked, nasal distress was an affliction we British shared with the Romans on account of our changeable and dampish weather. ‘Bastard climate,’ fumed Harry, ‘saw off Julius Caesar – soon went pissing off back to Rome. Couldn’t stand it!’

So Harry settled himself in just behind me, on one corner of the ground-sheet. We had no chairs, but the bank was level and sloped gently to the water, making a natural seat. A rod rest I cut from the bank-side branches. Eight inches from the hook I nipped enough shot to sink the Bismarck. I pinched on a bit of bread flake and cast out into the searing spotlight of my brand new Ever Ready ‘Space Beam’. The float sat dumpily in the water, brilliantly yellow in the light of the torch.

A brisk breeze had sprung up and it had become chilly. The branches of the trees swayed and the float drifted out of view. I swung the torch beam across the water and found the float again, but a sudden eddy of wind pushed it back the other way. Back and forward went the float like a leaf in a storm.

‘Pack it up God!’ moaned Harry (who, as a devout heathen, still believed in divine intervention if one’s plea or complaint was expressed with sufficient vigour). ‘I’m beginning to feel dizzy watching the bugger!’

Forward and back went the float for what seemed like an eternity.

‘Those monks, Tone,’ observed Harry, ‘relied on this pond for their scoff. Bugger that. Must have been thin bastards.’

Every time the float changed direction Harry asked if it was a run. ‘No Harry, it’s just the wind,’ I replied each time, with increasing frustration. I hadn’t used a plummet. I had just guessed the depth and set the float, so it was free to travel along like a boat. Then suddenly, the float just carried on and on into the darkness. I struck, and felt resistance. I stood up, and put a foot in the water. I pulled back, and fell on top of Harry. The line zinged out against the reel ratchet as I struggled to keep the rod upright and to regain my balance.

‘I’ll get out of your way,’ offered Harry, in the manner of Captain Oates.

‘Jesus, Harry!’ I yelled, ‘just grab the net and shine the torch down by my feet.’ I was panicking and Harry was dithering.

‘All right, Baws,’ he soothed, ‘keep calm.’

I had lost all contact with the fish and was merely flailing about, but I began to retrieve line. Then the resistance again, to my left, as I judged, about ten yards out. Slowly I made headway and could make out the outline of the float on the taut line. The fish surfaced and swirled, and Harry slid the net under my first, and last, Priory Carp.

Harry and I faced each other, and we hugged and we laughed and we jigged up and down. It was a tiny fish, by carp standards even then: about two pounds, I guess. But it formed a covenant between Harry and me and fishing and friendship.

We fished the Priory all that summer and never had another bite.

CHAPTER 3

Cunning Men

‘Whenever the moon and stars are set, Whenever the wind is high, All night long in the dark and wet, A man goes riding by, Late in the night when the fires are out, Why does he gallop, and gallop about?’

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSONWindy Nights (from A Child’s Garden of Verse)

Who would have believed that the obsessive, kempt Harry I met at his home and the relaxed, rakishly-attired Harry who fished with me that first night at the Priory were one and the same man? Now he was apparently untroubled by the dirty hands and the grubby clothes acquired after a night spent on the banks of a muddy pond; blemishes which his City persona would never tolerate. His voice too had changed; the strident vocal delivery which was so noticeably clipped and formal when Harry was dressed in his City suit, or kitted out in his khaki-for-the-weekend army wear, had mellowed to become friendly banter and brisk repartee.

His grandiose self-image however, remained unaffected. Harry, in his general demeanour, was confident of being instantly recognised as a member of the gentry. Whilst in no way a snob, he expected to be accorded all due rights and privileges of that curiously intangible and diminishing class.

Harry was an avid reader, often using his choice of reading material to bolster his expectations, as if by some strange alchemy or osmosis his mere contact with the written word would serve to reveal his true class identity to the cognoscenti. He mainly sought out non-fiction works and historical novels of the Georgian era, particularly the Regency, as the period with which he identified most strongly. But he was equally fascinated by tales of notable English eccentrics and the history of ancient Egypt, with the unsettling result that one moment he was identifying with a Regency dandy or a famous English eccentric or a member of the Hellfire Club, and the next he was insisting that he might well be the reincarnation of an Egyptian Pharaoh.

Even if he had no substantial claim to an actual title, he believed that the reward of land and wealth which were due to him by grand design would somehow be duly granted. Until the arrival of that happy day, Harry, reluctant gentleman-in-waiting, would continue to dispense a certain noblesseoblige. This mainly took the form of large tips for serving staff and extravagant expenditure on rounds of drink in pubs until his money ran out – behaviour generally accompanied by much patting of his wallet pocket and cries of ‘This one’s on me, boy!’

Harry had plotted out for himself two potential routes to his inevitable elevation. Firstly, there was mention of a family tie to a rather grand and ancient firm of crystal glass makers, holders of a Royal Warrant, (as if this connection was ennobling in itself).

Of possibly greater substance was a rumoured family relationship to a certain Canadian who, while having a background ‘in trade’ (like Harry), was nevertheless granted a baronetcy, in recognition of his business acumen and military success (or it might have been the other way round). This personage was at one time possessed of a considerable tract of real estate in Canada, including a magnificent Gothic castle. Any remote hopes of inheritance that Harry entertained in his fantasies were frustrated when swingeing taxes plunged the unfortunate baronet into debt and near bankruptcy.

‘The man was a bloody fool!’ declared Harry unsympathetically. ‘Like owning a Rolls Royce and not knowing how to drive.’ This was an expression he employed quite frequently. He used it to describe anyone who, blessed with opportunities and/or qualifications, (either or both of which, in his opinion, led automatically to wealth and success), failed to take full advantage of them. Not that Harry was expressing envy, (he said), just stating the obvious. Namely, that he would have made a resounding success of things had he the good fortune to be in that position himself.

Walking home that mid-morning from the Priory, our talk was of nothing but fishing and the events of the previous night. We began again to mull over venues of our youth where we might still go fishing. One such spot was Greenacres, a farm pond in Hadleigh where I had often gone as boy. Not too far away, it was still well-known locally as a day ticket water. The rumour was that the owner was thinking of selling up soon and so he was not currently too particular about the presentation of fishing licences or the observance of the closed season. I mentioned this to Harry.

‘You want to be careful there, Tony.’

‘Why, Harry, you’re not worried about poaching again after last night are you?’

‘No, Baws, not likely. Adds to the fun. Still, I’d be careful if I were you.’

‘Greenacres isn’t a dangerous place to fish is it?’ I asked. As I recalled, it was not very deep and there were firm, easily accessible banks all round.

‘No, nothing like that,’ said Harry measuring his words. I was too exhausted to be teased and Harry’s mystery was beginning to annoy me.

‘What have you heard about it then? Hooligans? Trouble? Come on, what’s the problem?’

Harry paused before answering.

‘Did you ever hear of ‘Cunning’ Murrell’,’ asked Harry, ‘the ‘Wizard of Hadleigh’?’

I tried then to recall what people in Hadleigh had looked like when I was a boy. Faces came back to me: sinister, brooding men in dark clothes and hats, and women with small eyes, hooked chins and facial hair. I had always thought these people were normal in a small country village.

‘No, I don’t think so.’

‘He lived in a cottage opposite Hadleigh Church,’ continued Harry. ‘There were witch families in Hadleigh and Rochford and Canewdon. James Murrell, ‘Cunning’ Murrell as he was known, was their master.’

‘You’re pulling my leg, Harry.’

‘No, honestly Tony. I’m not joking.’

‘Harry, leave off!’ I could see that he meant it though. ‘Okay. What did he do then, this wizard?’

Harry paused again, savouring the capitulation of his audience before speaking.

‘His main business was making potions. He used to brew them up from people’s hair or skin or nails, mix them with the juice of wild plants and then have them sealed in iron bottles by the local blacksmith. ‘Witch bottles’ they were called.’

It sounded foul, but there was a blacksmith’s forge in Hadleigh, that much was true.

‘And what did he do with these iron bottles?’

Harry started to explain. ‘Well, say someone came to Murrell and told him that they were under a spell or a curse…’

‘What sort of curse?’

‘Oh, I don’t know – failed crops, ugly wife, cow with the shits – that sort of thing. Anyway, people would collect this stuff from whomever they said had laid the curse and Murrell would make up one of his witch bottles. Then he would go round to the house of the guilty party when they weren’t at home, and put the bottle in their fireplace.’

At this point, Harry’s face took on a slightly demonic look. ‘Next time they lit a fire, whoosh! The bottle exploded with the heat and all this boiling stuff shot out.’

‘And?’ I asked, intrigued now.

‘It would break the spell or lift the curse,’ replied Harry triumphantly.

‘Must have made a mess of the living room, eh?’

Harry came over all serious, and gazed into the distance. ‘I wouldn’t joke about these things Tony,’ he observed darkly. ‘You never know.’

I had the feeling that if Harry did believe in anything supernatural, it would tend towards Hell rather than Heaven. Best to move on.

‘So what else did he do, this wizard bloke?’

‘Well,’ said Harry, smiling again, ‘he had a magic mirror. He could find things and tell the future. And he had a magic telescope that could see through walls.’

‘That would have made the neighbours careful,’ I mused, ‘especially the women.’

‘Baws!’ said Harry in mock seriousness, ‘I’ll tell Suzie.’

‘So, this wizard, Harry. Anyone seen him recently?’

‘Oh yes. People say they still see him sometimes in Hadleigh. He rides around at night on a black horse, whistling up witches.’

Harry’s tale conjured up images of a song they taught us at infant’s school, about a mysterious mounted man galloping through the night, and how it used to terrify me. As a small boy I lay in bed in the dark of winter at our house in Hadleigh, listening in fear to the wind rattling the windows, watching the rain lash down and the clouds scud across the moon, my ears pricked for the sound of beating hooves.

‘It’s a load of old cobblers, Harry.’

‘Well, he was a shoemaker to start with!’ Harry grinned.

‘Come on, it’s all nonsense.’

‘Don’t you be so sure, Baws. There are lots of thing we don’t know about. Ask Suzie, she’s fey.’

‘What do you mean, ‘fey’?’

‘She’s fey, Baws. I can tell.’

Was Harry really telling me that his stepdaughter, with whom I had fallen deeply in love, was a witch? Undaunted, I decided we must give Greenacres a try sometime soon: gallopers, cobblers, wizards or no.

My father was still alive when I was a small boy in Hadleigh. He was for a time, like Harry, a travelling salesman. He began by selling furniture and later cosmetics. But that work dried up as war loomed, and he found himself reduced to working in the small, dark, damp, clothing factories of the East End of London – the sweat shops. He became a garment presser. The steam, the poor sanitation, the heat and the constant wielding of the heavy pressing irons and Hoffman Press dragged his health down. He contracted tuberculosis before the outbreak of the Second World War and was declared unfit for military service. He died of the disease in 1944, aged only 29.

As my father became progressively unwell, and with a small child to raise, an escape to the countryside away from the grime of London must have seemed like heaven. Fresh air and rest were all that were on offer at the time to combat TB. Somehow enough money was found to make the move and pay the rent. After short stays in New Bradwell in Buckinghamshire, then in a house on the outskirts of Peterborough, we ended up in Essex.

My Dad was archetypically tall, dark and handsome before illness ravaged his fine body. He was a good swimmer and an amateur boxer at club level. For a short while he even served in the City of London Police force as a volunteer, until he was too ill to continue. Those who ‘stayed at home’ during the war, but were not involved in reserved occupations, were accepted into voluntary auxiliary services fairly readily, without much scrutiny of their past records, medical or otherwise. The Government welcomed them into the war effort to help in any way they could.

On the other hand, non-serving male civilians were sometimes vilified for a wrongly-perceived lack of patriotism. ‘Why aren’t you in uniform? Why aren’t you out there helping our boys?’ That kind of remark was commonplace. Being Jewish, we were also subject at times to a degree of anti-Semitism from these short-sighted bigots, a double blow for my father. But most people were kind and helpful and welcomed us into the local community.

Hadleigh back then was a sleepy village. Most of my young days were spent playing in open fields or woods near home. At the bottom of the road ran a tributary of Prittle Brook, that very same stream which had provided the entrance route for Harry and me on our furtive nocturnal foray into the Priory.

The water at this spot meandered along the bottom of a deep channel. To us youngsters, it might as well have been the Grand Canyon. The challenge was to ride your bike down one bank, across the brook and up the other side without stopping. Getting wet was an acceptable hazard, but avoiding contact with the vicious waterside stinging nettles which grew on both sides of the banking – that took real skill.

Here – before the road was metalled and extended and the houses and shops sprang up and the brook was diverted along a deep concrete cutting – was a small field. Flanked by birch, oak and hazel trees and edged by tall bracken, a footpath led northwards to join a bridle path.

At the junction of these two paths was a pond and here we boys fished for Great Crested Newts. The method was simple. All you had to do was tie a small worm securely to a length of thick cotton braid, with a matchstick tied further up the ‘line’ as a rudimentary float. The newts gorged the worm and they could then be lifted gently from the water, stubbornly refusing to spit out the worm until it was retrieved from their gullets with a firm pull. I was so successful at this form of ‘fishing’ that not only did I stock the pond in my back garden with newts, but I was able to sell the surplus to local pet shops to supplement my pocket money. My mother was forever retrieving newts that did not take to pond life and had emigrated to the house. Here she found them; in the pantry, under the carpet or behind the kitchen cupboard.

Towards Hadleigh the bridle path ran parallel to an unmade road – Scrub Lane. Halfway along lay Greenacres, a small-holding owned by Ken, a young farmer who lived there with his wife in a rambling house, surrounded by pigsties, barns, sheds and semi-derelict outbuildings. On the other side of the road were two arable fields which Ken also owned, and behind the farmhouse lay Greenacres Pond. I remembered going there as a boy, not to fish, but just to hang out with the older kids, and in particular with Ginger Padmore, a local hero.

Now that there was a prospect of revisiting Greenacres with Harry, memories of Ginger flooded back. Ginger was a master of many skills: groping, smoking, fishing, thieving and football. A small boy could learn a lot from Ginger. I once saw him steal a football from a local shop by the simple expedient of stuffing it up his jumper, turning on his heels and walking out. His approach to girls showed similar finesse; full-on groping and boasts about how he had felt Jenny’s or Jane’s ‘this and that’. I had no personal experience at my tender age of what ‘this or that’ truly were, but I knew they were infinitely desirable.

I remembered how Ginger would fish, standing in the shallows of Greenacres Pond on bright summer days; trousers rolled up to his thighs, a cigarette in the corner of his mouth, catching small roach and gudgeon. These he placed in a half-submerged butler sink which had somehow found its way into the water. With the plug hole stopped up with clay, it made an excellent short-stay aquarium. If I was indeed to make it back to my childhood haunt, this time in the company of Harry, I half hoped that the old butler sink would still be there.

CHAPTER 4

A Pig’s Breakfast

‘Singing hey piggy-pig, Do a little jig, Follow the band, Follow the band all the way.’

HARRY (after WW2 squaddie song)

When I arrived at the flat, Harry was still busy beating up that day’s paperwork. Waiting until he had finished, I broached the subject of the fishing arrangements. It was a glorious late Friday afternoon in early May. Our rekindled enthusiasm for fishing had continued to grow apace. The warm, settled conditions only served to stoke the fires of our mania. Where others might long for a swim or a sunbathe after work in this splendid weather, all that Harry and I yearned for was the spell-binding sight of a still float on calm water.

Suzie and I had planned to go out that evening, and Harry also had things to do, but all he and I could really focus on was fishing. We agreed to meet at Greenacres Pond early the next morning. I was to go by bus, while Harry announced rather grandly that he would book a taxi to take him there in the small hours. I thought it tactful not to mention that, if Harry’s planned fishing attire for the journey to Greenacres was anything like the outfit he had sported for the Priory mission, a cautious taxi driver might just refuse the fare.

Billie again offered to prepare some food for both of us.

‘Remember, Harry,’ she cautioned, having learned of the ‘Great Priory Park Provisions Disaster’, ‘leave Tony’s food alone this time! I’ll make up two separate boxes. There’ll be plenty for both of you.’

I was not totally convinced.

‘There’ll be a full moon tonight, Tony,’ said Harry.

‘Should be good fishing then. Can’t wait.’

‘He used to have a dog,’ said Harry.

I was stumped by this non sequitur.

‘Who did?’ I asked

‘Cunning Murrell.’

‘Oh him. What was it called then?’

‘Black Shugg.’

‘What breed was it?

‘A cross between a sheepdog and a pug’ said Harry with a straight face.

‘Hmm,’ I mused aloud, ‘sounds familiar.’

‘Oh very good, Baws! Actually most witches and wizards had cats as their familiars.’

‘I’ll let you know if I spot him Harry,’ I promised. ‘See you later then. ‘Night Mrs P.’

Suzie and I went off to catch an early performance at the cinema in Southend. During quiet moments in the film, I would close my eyes and my mind would wander. ‘What are you thinking about at this moment?’ Suzie would ask softly, the way young lovers do. I could not confess to her that in my mind were images of a rod in its rest, and a float on calm, green water; a beautiful, still float.

After the show, I escorted Suzie back to the flat, holding her hand and feeling very much in love. But instead of coming in for a coffee and a goodnight cuddle as usual, I briskly kissed her goodnight and rather unromantically scuttled off home to change. Picking up my fishing things, I caught a bus to Hadleigh around half past ten, aiming to relax at Greenacres until Harry arrived. I wasn’t going to start fishing without Harry.

I called at the farmhouse to pay Ken and try to sort out somewhere to sleep.

‘You’re welcome to stay in the barn, just beyond the sties,’ said Ken. ‘But no smoking in there, mind!’

I explained that Harry would be arriving later, paid him for the two of us, thanked him and wished him good evening, stubbing out my cigarette ostentatiously on the ground in front of us. I made my way past the sties, patting the pigs as I went. It was a perfectly still night, illuminated by a huge, bright, white, full moon. I could hear low voices from the far side of the pond, but there was no one on the side where I was hoping to set up with Harry.

Tense and excited at the prospect of the night’s fishing, I entered the barn. It was the first time in my life that I had slept on straw. I had often played in and around the stacks as a kid, and sometimes thought how great it must be to curl up and sleep in a barn. I arranged some bales, set my alarm for a quarter to three and tried to settle down.