Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

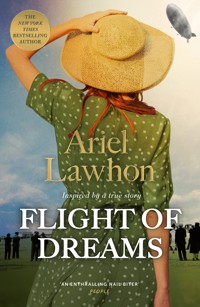

'At every page Lawhon keeps us guessing' The New York Times 'A fascinating blend of love and murder, big dreams and betrayal, history and pure imagination – I could not put it down' Sara Gruen, author of Water for Elephants 'A writer to watch' J.T. Ellison, author of What Lies Behind A SUSPENSEFUL, HEART-WRENCHING NOVEL BASED ON A TRUE STORY FROM THE BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF THE FROZEN RIVER On the evening of May 3rd, 1937, ninety-seven people board the Hindenburg for its final, doomed flight. Among them are a frightened stewardess who is not what she seems; the steadfast navigator determined to win her heart; a naive cabin boy eager to earn a permanent position; an impetuous journalist who has been blacklisted in her native Germany; and an enigmatic American businessman with a score to settle. Over the course of three champagne-soaked days, their lies, fears, agendas, and hopes for the future will be revealed - and one in their party will set a plot in motion that will have devastating consequences for them all. Flight of Dreams is a fiercely intimate portrait of the real people on board the last flight of the Hindenburg. Behind them is the gathering storm in Europe and before them is looming disaster. But for the moment they float over the Atlantic, unaware of the inexorable, tragic fate that awaits them. Brilliantly exploring one of the most enduring mysteries of the twentieth century, Flight of Dreams is that rare novel with spellbinding plotting that keeps you guessing till the last page and breathtaking emotional intensity that stays with you long after. FIVE STAR RAVE READER REVIEWS - 'Delightful, insightful, SUSPENSEFUL and also horrific' - 'A poignant and ENTHRALLING tale based on the world famous Hindenburg disaster ... ADDICTIVE' - 'The prose is wonderful, the details are rich, and THE PULL OF THE PAST is on every page' - 'Really STELLAR. Suspenseful, tightly plotted, and racheting its way to a MERCILESS climax ... A TERRIFIC read' - 'With Lawhon's gift for writing memorable characters, sharp dialogue, and enthralling suspense, FLIGHT OF DREAMS becomes an UNPUTDOWNABLE EPIC TRAGEDY' - 'A true gem of historical fiction'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 600

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Other Books by Ariel Lawhon

The Frozen RiverI was AnastasiaThe Wife, the Maid, and the Mistress

For my husband, Ashley, who has taught me the meaning of sacrificial love.Also for Marybeth. We’re even now.And in loving memory of my grandmother, Mary Ellen Storrs. I never thought to ask her if she remembered the Hindenburg until it was too late.

To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly be broken.—C. S. Lewis, The Four Loves

U.S. Commerce Department Board of Inquiry

Hindenburg Accident HearingsMay 10, 1937

Naval Air Station, Main Hangar, Lakehurst, New Jersey

Please inform the Zeppelin company in Frankfurt that they should open and search all mail before it is put on board prior to every flight of the Zeppelin Hindenburg. The Zeppelin is going to be destroyed by a time bomb during its flight to another country.

—Letter from Kathie Rusch of Milwaukee to the German embassy in Washington, D.C., dated April 8, 1937

This was not the first bomb threat, correct?” The man in the black glasses lifts the letter and waves it before the crowd. “Did anyone bother to count how many there were? Or, for God’s sake, to believe them?”

Max thinks the man’s last name is Schroeder, but he can’t remember, and in truth he doesn’t care. He’s a fool if he believes that crazy woman from Milwaukee and her letter. Not that anyone else in the room is concerned with Max’s quiet derision. People whisper and nod their heads like mindless puppets at the idea of sabotage. Search the mail, she said. There’s a bomb on board, she said. It’s a popular theory, especially now, with the wreckage still sprawled in the field outside. But no one cares about the truth. They prefer theatrics and conspiracy theories. And Schroeder is happy to provide them. He is ringmaster of this circus. He will make sure the mob is entertained.

Wilhelm Balla limps his way through the crowded hangar to stand next to Max. He escaped the crash with little more than a sprained ankle, but Max suspects he’s exaggerating even that. He leans a bit hard to the left with each step, showing off. Letting the world know he’s injured.

Balla searches Max’s face for clues to his emotional state. “Emilie?” he asks.

“What about her?”

“She’s prepared for the trip back to Germany?”

Max turns his attention to the spectacle at the front of the room. “I haven’t asked.”

“Let me know when she is. I’d like to say good-bye.” Balla clears his throat. “They have me booked on the Europa with Werner on the fifteenth. How is she going home?”

“On the Hamburg. With the others. It sails in three days.”

Wilhelm Balla is not a man who often displays emotion. It is up for debate whether he actually has a pulse. But this surprises him. “You aren’t traveling with her?”

Max leans his head against the window. The cool glass feels good against his throbbing temple. He hasn’t been able to shake this headache since the crash. No surprise, really, all things considered. “There are many things outside of my control, not the least of which is travel.” He taps the envelope in his pocket with the pad of one finger and then draws his hand away. “I don’t testify until the nineteenth. I’ll take the Bremen the following day.”

Balla gives him the long, appraising look that Max finds so aggravating. “How many times have you read Emilie’s letter?”

“Once was enough.” It’s a lie. But he has no interest in confiding in Balla. Not after the trouble he caused.

From his position beside the window, Max can see the airfield and the charred skeleton that lies crumpled beside the mooring mast. He closes his eyes and tries to push the sight away, but to no avail. The images are there—will be there, he is certain, for the rest of his life; a single tongue of blue flame licking the Hindenburg’s spine, a fluttering of silver skin followed by the shudder of metallic bone, a flash, barely visible to those on the ground below. Bedlam. He is certain that the passengers close enough to see the explosion never heard it. They were simply consumed as the backbone of the great floating beast snapped in half. Thirty-four seconds of catastrophic billowing flames, followed by total, profound destruction. In half a minute the airship went from flying luxury hotel to smoking rubble—a skeleton lying crumpled in this New Jersey field, blacked by smoke and flame. No, these are things he will never forget.

Already the hearings have begun. There will be testimony. Reporters and flashbulbs. A different sort of pandemonium and a desperate attempt to understand why. There will be political conflagration. Headlines screaming out their theories in bold print, punctuated for emphasis. accident! sabotage! Fingers pointing in all directions and, of course, the subtle, insinuating whispers. The quiet placing of blame. Max wonders if their names and faces will be forgotten when the headlines are replaced by some new tragedy. Will anyone remember the particulars of those who fell from the sky a few short days ago? The vaudeville acrobat. The cabin boy. The journalists. An American heiress. The German cotton broker and the Jewish food distributor. A young family of German expatriates living in Mexico City. Chefs and mechanics. Photographers and navigators. The commander and his crew. A small army of stewards and Emilie, the only stewardess. Old men and young boys. Women past their prime and a fourteen-year-old girl who loved her father above all else. Will anyone remember them?

Bureaucrats measure loss with dollar signs and damage control. Already they have begun. There is standing room only in this hangar. But Max knows that to him, the cost will always be measured by lives lost. He also knows that in nine days, when his time comes to sit in that chair and give testimony, he will not tell them the truth. Instead he will look over Schroeder’s shoulder at a point on the far wall and tell the lie he has already decided upon. It is the only way to protect Emilie. And the others. Max Zabel will swear before God and this committee that it was an uneventful flight.

Day One

Monday, May 3, 1937—6:16 P.m., Central European Time

Frankfurt, Germany

3 days, 6 hours, and 8 minutes until the explosion

—

Here is the goal of man’s dream for many, many generations. Not the airplane, not the hydroscope, man has dreamed of a huge graceful ship that lifted gently into the air and soared with ease. It is come, it is completely successful, it is breathtakingly beautiful.

—Akron Beacon Journal

The Stewardess

It’s a bad idea, don’t you think?” Emilie asks, as she stands inside the kitchen door, propping it open with her foot. “Striking a match in here? You could blow us all to oblivion.”

Xaver Maier is young for a head chef, only twenty-five, but he wears the pressed white uniform—a double-breasted jacket and checkered pants—with an air of authority. The starched apron is tied smartly at his waist, the toque fitted snuggly to his head. He gives her that careless, arrogant smirk that she has begrudgingly grown fond of and puts the cigarette to his lips. He inhales so deeply that she can see his chest expand, and then blows the smoke out the open galley window into the warm May evening. “Ventilation, love, it’s all about proper ventilation.”

The way he says the word, the way he holds his mouth, is clearly suggestive of other things, and she dismisses him with a laugh. Xaver Maier is much younger than Emilie and a great deal too impressed with himself. “At the moment, love, it’s about aspirin. I need two. And a glass of water if you can summon the effort.”

The kitchen is small but well ordered, and Xaver’s assistant chefs are busy chopping, boiling, and basting in preparation for dinner. He stands in the center of the melee like a colonel directing his troops, an eye on every small movement.

“Faking a headache?” he asks. “Poor Max. I thought you’d finally come around. We’ve been taking bets, you know.”

“Don’t,” she says, flinging a drawer open and shuffling through the contents. She has made it perfectly clear that all discussion of Max is off limits. She will make up her mind when she is good and ready. “I went to the dentist yesterday, and the left side of my jaw feels like it’s about to fall off.” She leaves the drawer open and moves on to another.

“Usually when a woman tells me her jaw is sore I apologize.”

Emilie opens a third drawer. Then a fourth. Slams it. “I had a tooth filled.” She’s impatient now. And irritated. “Aspirin? I know you keep it around here somewhere.”

He follows behind her, shoving the drawers shut. “Enough of that. You’re as bad as the verdammt Gestapo.”

“What?” She looks up.

Xaver reaches behind her head and lifts the door to a high, shallow cabinet attached to the ceiling. He pulls out a bottle of aspirin but doesn’t hand it over. “I’m glad to hear you don’t know everything that happens aboard this airship.” He taps the bottle against the heel of his hand, making the pills inside rattle around with sharp little pings. “There’s still the chance of keeping secrets.”

“You can’t keep secrets from me.” She holds out her hand, palm up. “Two aspirin and a glass of water. What Gestapo?”

Xaver counts them out as though he’s paying a debt. “They came because of the bomb threats. Fifteen of them in their verdammte gray uniforms.”

“When?” She takes a glass from the drying board above the sink and fills it with tepid water. Emilie swallows her pills in one wild gulp.

“Yesterday. They searched the entire ship. Took almost three hours. I had to take the security officers down the lower keel walkway to the storage areas. The bastards opened every tin of caviar, every wheel of aged Camembert, and don’t think they didn’t sample everything they could find. Looking for explosives, they said. I was out half the night trying to find replacements. And,” he pauses to take a long, calming drag on his cigarette, “you can be certain that frog-faced distributor in the Bockenheim district didn’t take kindly to being woken at midnight to fill an order for goose liver pâté.”

She has heard of the bomb threats, of course; they all have. Security measures have been tightened. Her bags were checked before she was allowed on the airfield that afternoon. But it seems so ridiculous, so impossible. Yet this is life in the new Germany, they say. A trigger-happy government. Suspicious of everyone, regardless of citizenship. No, not citizenship, she corrects herself, race.

Emilie looks out the galley windows at the empty tarmac. “Did you know they aren’t letting anyone come for the send-off? All the passengers are waiting at a hotel in the city to be shuttled over by bus. No fanfare this time.”

“Should be a fun flight.”

“That,” she says with a grin, “will have to wait until the return trip. We’re fully booked. All those royalty-smitten Americans traveling over for King George’s coronation.”

“I’d take a smitten American. Preferably one from California. Blondine.”

Emilie rolls her eyes as he whistles and forms an hourglass figure with his hands.

“Schwein,” she says, but she leans forward and gives him a kiss on the cheek anyway. “Thank you for the aspirin.”

The kitchen smells of yeast and garlic and the clean, tangy scent of fresh melons. Emilie is hungry, but it will be some time before she gets the chance to eat. She is lamenting her inadequate early lunch when a low, good-humored voice speaks from the doorway.

“So that’s all it takes to get a kiss from Fräulein Imhof?”

Max.

Emilie doesn’t have to turn around to identify the voice. She is embarrassed that he has found her like this, flirting—albeit innocently—with the ship’s resident lothario.

“I worked hard for that kiss. You should do so well,” Xaver defends himself.

“I should like the opportunity to try.”

The matter-of-fact way he says it unnerves her. Max looks dapper in his pressed navy-blue uniform. His hair is as dark and shiny as his shoes. The gray eyes do not look away. He waits patiently, as ever, for her to respond. How does he do that? she wonders. Max sees the bewilderment on her face, and a smile tugs at one corner of his mouth, hinting at a dimple, but he wrestles it into submission and turns to Xaver.

“Commander Pruss wants to know tonight’s dinner menu. He will be dining with several of the American passengers and hopes the food will provide sufficient distraction.”

Xaver bristles. “Commander Pruss will no longer notice his companions when my meal arrives. We will dine on poached salmon with a creamy spice sauce, château potatoes, green beans à la princesse, iced California melon, freshly baked French rolls, and a variety of cakes, all washed down with Turkish coffee and a sparkling 1928 Feist Brut.” He says this, chin lifted, the stiff notes of dignity in his voice, as though citing the provenance of a painting and then squints at Max. “Should I write that down? I don’t want him being told I’m cooking fish and vegetables for dinner.”

Max repeats the details verbatim, and Xaver gives a begrudging nod of approval.

“Now, out of my kitchen. Both of you. I have work to do. Dinner is at ten sharp.” He shuffles them into the keel corridor, then closes the door. Xaver might be an opportunist—he would gladly take a real kiss from Emilie if she were to offer one—but he knows of her budding affection, and he’s more than willing to make room for it to bloom further.

Max leans against the wall. His smile is tentative, testing. “Hello, Emilie. I’ve missed you.”

She’s certain the chef is on the other side listening. She can smell cigarette smoke drifting through the crack around the door. He would like nothing better than to dish out a portion of gossip with the evening meal. And Emilie would love to tell Max that she has missed him as well in the months since their last passenger flight. She would love to tell him that she has very much looked forward to today. But she doesn’t want to give Xaver the satisfaction. The moment passes into awkward silence.

“Listen . . .” Max reaches out his hand to brush one finger against her cheek when the air horn sounds with a thunderous bellow from the control car below them. The tension is broken and they shift away from each other. He shoves his hands in his pockets and stares at the ceiling. “That is such a hateful noise.”

Emilie tugs at the cuff of her blouse, pulling it over the base of her thumb. She doesn’t look at Max. “We’re about to start boarding passengers.”

“I really must see if they can do something about that. A whistle, maybe?”

“I should get out there and greet them.”

“Emilie—”

But she’s already backing away, coward that she is, on her way down the corridor to the gangway stairs.

The Journalist

Gertrud Adelt has no patience for fools. In her opinion, Americans fit the description almost categorically. The one sitting across from her now is drunk, leaning precariously into the aisle and singing out of tune. He shouts the words to some bawdy drinking song as if he were dancing on a bar instead of sitting in a bus filled with exhausted passengers. His voice is bombastic, loud and abrasive, and mein Gott, please make him stop, she thinks. She turns her pretty mouth to her husband’s ear and quietly asks, “Can’t you do something?”

Leonhard looks at his watch, then up at the heavily listing American. “He’s been drinking since three o’clock. I’d say he’s managing quite well, all things considered.”

“He’s obnoxious.”

“He’s happy to be leaving Deutschland. There’s no crime in that.” The look he gives her is tinged with understanding. Who wouldn’t want to leave this country? Anyone but the two of them, most likely. As it stands, the thought makes her ache. Their son, little more than a year old, is in the care of Gertrud’s mother at the insistence of a senior SS officer. Blackmail by way of separation. Return as promised, or else. In recent months, Germany has grown adept at making sure that valued citizens do not defect.

The Adelts have spent the better part of their day waiting in the lobby of Frankfurt’s Hof Hotel. Waiting for lunch. Waiting for a telegram from Leonhard’s publisher. Waiting for the government to change their minds and revoke permission for the trip altogether. At four o’clock the buses arrived to shuttle them to the Rhein-Main Flughafen. But then they waited while their luggage was searched and their papers checked and double-checked and triple-checked. The first indication that Gertrud was ready to snap came when her bag was weighed.

“I’m sorry, Frau Adelt,” the customs officer informed her. “Your bag is fifteen kilos over the twenty-kilo limit. You will have to pay a fine of five marks for every extra kilo.”

Gertrud looked around the bar, eyeing each of the men waiting to board the buses. She sniffed and rose to her full height. “Then it’s a good thing I weigh twenty kilos less than the average passenger.”

The customs officer was not amused, and Leonhard handed over the seventy-five marks before Gertrud could further complicate the process. By the time they were finally allowed on the bus and took their seats, she was exhausted and entirely without coping skills to deal with fellow passengers.

Now, the long muscles along her spine feel ready to snap. They are tight and aching, strained by her rigid posture over the last few hours. The American’s voice grinds against her skull like mortar against pestle. The back of her eyes hurt. Gertrud fights the irrational urge to reach across the aisle and strike his face. She tucks her hands between her knees instead.

Something outside the window catches the American’s attention and he drifts into silence. Gertrud sighs, squeezes her eyes shut, and leans her head against Leonhard’s shoulder. The bus rumbles along steadily for a few moments, vibrations coming up through the floor and into their feet. They are jostled by the occasional pothole—the broad paved streets of Frankfurt have fallen into disrepair, but fixing them hardly seems a priority to anyone. They soon pass a sign with a white arrow directing them to the airfield. The bus veers to the left, and an excited murmur runs through the passengers. Somewhere, behind them, a child cheers. Gertrud feels a twinge of anger that some other child is allowed to make the voyage while hers is forced to stay behind. The American, however, is energized by their near arrival and belts out the second verse of his drinking song. He leans toward her, eyes crossed, chuckling, and she recoils from his sour breath.

Leonhard grabs her wrist just as she’s about to lash out. “No,” he says. “Be good.” Her husband is twenty-two years older than she is, but time has not dulled his strength one iota. He puts two broad hands around her waist and lifts her up and over his lap. Leonhard deposits her neatly by the window, his body a wall between her and the American.

Gertrud offers a wry smile. “Good? You know that being good isn’t part of my skill set.”

“Now is not the time to talk about your many attributes, Liebchen. Humor me this once. Please?”

She can still hear the American, but she can no longer see him, and this is a great mercy. She gives Leonhard’s hand a squeeze of gratitude, then leans her forehead against the cool glass of the window. She tries not to think of Egon and his chubby, dimpled fists. His bright blue eyes. The soft brown hair that is just starting to coil above his ears. Gertrud thinks instead of the career she has worked so hard to build and how it lies in rubble behind her. Her press card having been revoked by Hitler’s Ministry of Propaganda. Troublemaker, that’s what they have branded her. In reality she has simply been a question asker. She is a good journalist. But she has never been a good rule follower. Or a good girl, for that matter, despite Leonhard’s admonition. Yet, even now, she cannot bring herself to regret the choices she has made this year.

A few minutes later the bus slows and turns onto the airfield. A great hangar looms in front of them, taller, wider, longer than any structure she has ever seen. And moored just outside is the D-LZ129 Hindenburg, almost sixteen stories tall and over eight hundred feet long. From their vantage point, Gertrud can barely make out the airship’s name written aft of the bow in a blood-red Gothic font, and farther back, the massive tail fins emblazoned with their fifty-foot swastikas. The irony is not lost on her. They will make this trip, but only under a watchful Nazi eye.

“Mein Gott,” Leonhard whispers, placing one large, calloused hand on her knee.

The zeppelin floats several feet off the ground, moored on either side by thick, corded landing lines. The only parts of the actual structure that touch the ground are the landing wheels and a set of retractable gangway ladders that lead up and into the passenger decks. They will board there, directly into the behemoth’s swollen silver belly. Gertrud stops herself from cracking jokes about Jonah and his infamous whale, but she does feel very much as though she’s about to be swallowed whole.

The ground crew scurries around, preparing to cast off, while the flight crew stands in a long, neat line near the gangway waiting to greet them. The American chooses this moment to finish his drinking song with one last, raucous burst.

Gertrud is up and out of her seat like a shot. She climbs over Leonhard, knees the American in the shoulder, and rushes down the aisle without regard for any of the other passengers. “I’m sorry,” she says by way of apology to the driver. “I’m feeling sick. I need fresh air.” The bus is still rolling to a stop, but the driver swings the door open and Gertrud takes the steps two at a time, only pausing to breathe when her feet are planted firmly on the ground. She stands off to the side, waiting for Leonhard, while the other passengers unload and venture toward the ship, forming a line in front of the crew. She clenches her fists and inhales deeply through her nose. For the first time since early that afternoon she can neither see nor hear the American. Gertrud takes another deep, ragged breath and stands with her eyes closed in the middle of the tarmac, soaking in the fresh, cool evening air. She can feel the tension begin to lessen in her neck.

A bevy of ground crew come to collect the luggage stored in compartments beneath the bus, but Gertrud intercepts one of them and grabs a brown leather satchel. “I’ll keep this with me,” she says. “It’s mine.”

“Come along.” Leonhard has their tickets in hand, and he steers her to the back of the line. In front of them is a family of five. Two young boys jump up and down, barely able to contain their excitement, while their teenage sister holds her father’s hand and grins with unabashed delight.

“I can’t do this,” Gertrud whispers. “Egon—”

“Will be fine,” he says, finishing her sentence with certainty. “Three months. We can do this for three months.”

“He will think we have abandoned him.”

“He will not even remember our absence.” Leonhard sets his hands on her shoulders. He looks at her calmly, with a smile that does not reach his eyes. He appears lighthearted, jovial even. His voice, though, is low and measured and serious. “We will do what we have to do, Liebchen. And then we will return home to our son. Now, turn and give your papers to the steward. Do it with a smile if possible.”

They are greeted at the base of the gangway by the chief steward. His name tag reads heinrich kubis—neat, square little letters as neat and square as the man himself. He takes their paperwork, scrutinizes it, then runs the stubby end of one finger along his clipboard. “Ah. You are in one of the staterooms on B-deck,” he says. “Cabin nine, just aft of the smoking room. Your bags will be taken up, and you are free to board. If you follow these stairs all the way to the top you will have a lovely view of takeoff from the portside dining salon on A-deck.”

“May I take your bag, Frau Adelt?” Gertrud hears the voice, recognizes it as female, but does not acknowledge it. She stares instead at the rectangle of light at the top of the gangway stairs.

“Frau Adelt?” Again that voice. She ignores it.

Leonhard pulls the satchel from her hands. “Yes. Please. My wife would like that very much.”

“It will be with your things.”

Leonhard leads his wife up the steps, but it is as though she’s an automaton, stiff and leaden. “You were quite awful to that woman just now.”

His voice registers. “What?”

“The stewardess. The one who took your bag. You didn’t even look at her. You will have to watch that, Liebchen.”

Gertrud looks over her shoulder and sees the back of a tall, slender woman dressed in uniform. Her hair is dark and wavy and falls neatly to her shoulders. One of the ship’s officers approaches her, his hands tucked shyly in his pockets, and she laughs at something he says. The stewardess has the charming, musical sort of laugh that Gertrud has always envied in other women. She sniffs, irritated.

The gaze she levels at her husband borders on panic. “My mind is on other things right now. Yours should be as well.”

The Navigator

You’re staring at her again.”

Max turns to find a slow, amused smile disrupting the sharp angles of Wilhelm Balla’s usually stoic face. It looks ill-fitting on the steward, as though he has borrowed another man’s coat.

“Wouldn’t you?”

“I would go talk to her, not stand there like a pubescent boy with a secret crush.”

“It’s hardly a secret.”

“Get on with it, then.”

“Emilie is greeting passengers. And we’ve already said hello.”

For a man with such a blunt personality, Wilhelm Balla has razor-sharp insight. “Can’t have been much of a greeting. You didn’t kiss her.”

“How—”

The steward cuts him off by holding up his manifest—right between their faces—and reading from it. “It appears as though Frau Imhof is greeting the last of her passengers now. Journalists from Frankfurt. She will likely have a few scarce moments before boarding herself.”

Max can’t hear what Emilie says to the dismissive young woman, but she has to repeat herself. The journalist still doesn’t respond, and her husband finally tugs a satchel from her hands and passes it to Emilie with an apologetic shrug. Emilie looks slightly embarrassed, and Max takes a strong and immediate dislike to the journalists.

“Did she tell you I didn’t kiss her?” He clears his throat. “Did she want me to—”

“Go.”

The steward gives Max one hard shove. He stumbles forward and tucks his hands in his pockets because he doesn’t know what else to do with them. Emilie stands near the portside gangway holding the satchel and scowling at the couple as they whisper intently on their way up.

“Pay them no mind,” he mutters low, over her shoulder, so that his breath tickles her ear. “People go crazy when they fly. I’ve seen decorated soldiers lose their Scheiße.”

She laughs, loudly at first, and then lower, a gentle shaking of her shoulders. God, he loves her laugh.

“Are you going to commandeer every conversation I have over the next three days?”

“Are you going to kiss everyone but me?”

“I didn’t kiss either of them.”

“You kissed the cook.”

“Chef. And you sound petty. I can kiss who I like.”

He loves this about Emilie. How brassy and direct she is. They are well matched in spirit, if not height. Emilie is but an inch or two shorter than Max, and he constantly finds himself in the unusual position of facing her eye to eye depending on her footwear. He is tall; so is she, for a woman.

“Kiss whoever you like. As long as I’m the one you like the most.” He lowers his voice. “You did promise me an answer on this flight. Have you forgotten?”

Emilie is about to respond when they are interrupted by screeching tires.

Max grabs Emilie by the arm and pulls her back a step as the careening taxi lurches to a stop beside the airship. A small, wiry man leaps from the backseat, followed by a dog so alarmingly white that Emilie gasps. The new arrival surveys the curious onlookers as though he has come onstage for an encore. Max half expects him to bow. Instead, the dog barks and things disintegrate into bedlam. Three security guards, two customs officials, and the chief steward all descend on the strange little man as though he’s holding a detonator. But he fans his ticket and travel papers in front of his face without the least bit of concern.

“Joseph Späh!” he announces to no one in particular, and this time he does give a theatrical bow. He motions toward the dog. “And this is Ulla. We are so pleased to join everyone on this voyage.”

The ground crew searches his bags, and Späh hangs back to watch, quietly mocking their curiosity. One of the soldiers finds a brightly wrapped package and tears off the paper. He lifts a doll from the pile of tissue and appears somewhat disappointed at the find.

“It’s a girl, Dummkopf,” Späh says when the officer turns it over to check beneath the ruffled skirt.

It takes no small amount of time to verify that Joseph Späh is a legitimate passenger on board the Hindenburg, that Ulla’s presence and freight have been approved and paid for in advance, and to locate his cabin—which, as it turns out, is on A-deck near the dining room, much to Späh’s satisfaction. He seems delighted at the prospect of maintaining his role as entertainer.

Max and Emilie watch the entire spectacle in bemused silence, and he takes immense pleasure in the fact that she does not draw her arm away from his hand. He can feel the warmth of her skin through the thin sleeve of her dress. Max soaks it in. He has never given her more than a glancing touch before. This is progress.

Max’s reverie is broken by the guttural clearing of a throat. He turns to find Heinrich Kubis staring at his hand on Emilie’s arm. The chief steward drops two bulging mailbags at Max’s feet. “These are yours, I believe?”

He releases Emilie and lifts the bags. They are surprisingly heavy, but he’s determined not to show it. “So there’s the last of it. Commander Pruss said two more loads were coming on the bus.”

Emilie nods at the bags. “What’s this?”

“Max is our new postmaster,” Kubis says. He glances at Max and Emilie as though an idea has just occurred to him. “He will attend to those duties in his off hours.”

“His off hours? Meaning he won’t have any hours off?”

“You will have precious few yourself, Fräulein Imhof. And I’d highly suggest that you not spend them fraternizing with an officer in full view of the passengers.” He tips his head toward the control car. “Or the commander.”

Max is absurdly pleased that Emilie looks disappointed at this news. Perhaps she had imagined ways of filling his spare time? He takes a step back and clicks his heels sharply. Nods. “If you will excuse me, I need to get these stored in the mailroom before we cast off.”

Emilie is not pleased that their conversations seem to end on his terms, and he enjoys the lines of frustration that appear between her eyes. “Don’t you want my answer?” she calls after him.

“Send it by post!”

She may have something left to say, but he doesn’t wait to hear it. Max turns, a mailbag gripped tightly in each hand, and walks up the gangway. Instead of taking a sharp right and going up another set of stairs to A-deck, he turns left into the keel corridor and heads toward the front of the airship.

Max neatly sidesteps Wilhelm Balla. He has his hand on the elbow of a staggering American who is mumbling the words to some lewd drinking song, but the man slurs so badly Max catches only every other word.

“No. Your cabin is this way,” Balla says. “Nothing to see down there.”

Max offers the steward a cheerful smile. “Good luck with that.”

Balla expertly holds up the American with one arm while checking his manifest with the other. “The good news is that this Arschloch’s room isn’t on A-deck. I probably couldn’t get him up the stairs. The better news is that his cabin is right next to Kubis.”

The chief steward is a teetotaler and not generally fond of anything originating from America, whether people or products. Watching these two interact over the next few days should be interesting. Balla, at least, is smiling at the prospect. He shuffles off with the American, wearing the impish grin of a schoolboy anticipating some minor disaster.

The mailroom is down the corridor, on the left, just before the officers’ quarters, and Max has to drop the mailbags so he can unlock the door. All 17,000 pieces of mail were inspected by hand earlier that day in Frankfurt. The cutoff for letters to make this flight was three o’clock, and based on the weight of the last two bags, there was quite a last-minute rush. This is Max’s first flight as postmaster, having inherited the position from Kurt Schönherr for this year’s flight season, and he inspects the room carefully to make sure everything is in order.

The room smells of paper and ink and musty canvas, and in the dim light the piles of mail bear an uncomfortable resemblance to body bags. A bag marked köln hangs on a hook by the door, waiting for the airdrop later that evening. In the corner is a squat, black, protective container. Metal. Locked. Fireproof. And off-limits to everyone but him. Inside are pieces of registered mail. And the items that require special care or discretion. The key to this lockbox is on the ring at Max’s waist. Three hours ago he was given a small package, one hundred newly printed marks, and a promise that if the package is kept safe until their arrival in New Jersey, he would receive another hundred.

The parcel is inside the lockbox, and the box itself is, thankfully, still locked. Max scans the room one more time to make sure everything is in order. Then he pats the mailbag headed for Cologne and locks the door behind him.

The American

He isn’t drunk. Not even close. It would take more than three watered-down gin and tonics to make him stumble. But he leans on the steward’s arm just the same. A well-timed lurch, a garbled word here and there, and no one is the wiser. The easiest way to be dismissed is to appear inordinately pissed in public.

Before he’s shuffled away by the steward, the American takes note of the key ring clipped to the officer’s belt and which door leads to the mailroom. Its proximity to the control car is problematic—there will always be officers lurking about—but he can deal with that later. The keel corridor is long and narrow with walls that slant outward, and he and the steward have to stand aside to let others pass four times before they reach his stateroom. It wouldn’t be appropriate to deposit a wasted Yankee in someone else’s cabin, so the humorless steward checks his clipboard twice before shoving the door open and guiding him to the bed. The steward’s name tag reads wilhelm balla, and his white jacket is perfectly pressed, as are the corners of his mouth. The American takes a perverse pride in the steward’s disapproval.

“You’ve got the room to yourself, so there’s no need to worry about inconveniencing anyone else while you sleep this off.” The steward shrugs out from beneath one of the American’s leaden arms. The American tips backward into the berth, seemingly incoherent. “Dinner is at ten. You’ll be seated at Commander Pruss’s table, I understand?” He waits for a beat and then continues, not bothering to hide the disdain in his voice. “I’ll come collect you if you’ve not woken by then.”

The American does not respond. He counts to five after the door clicks shut. Then he sits up and straightens his jacket. The room is larger than is typical for a cabin on board an airship. Eight feet wide by ten feet long. One berth that can sleep two instead of bunk beds. But it’s the window that makes it worth the ticket price. Like the windows elsewhere on board, this one is long and narrow and set into the slanted wall. Unlike the observation windows on the promenade, however, this one does not open. The sink and writing desk are larger here than on A-deck—there’s a bit of room to spread out. The small, narrow closet has enough room to hang a handful of shirts and trousers, but the rest of his clothing will need to be stowed beneath the bed. No trouble, he only checked two bags, and the item he is most eager to find isn’t in either of them. The American stands in the middle of the room and turns in small quarter-circle increments, methodically taking note of every detail. The walls and ceiling are made of foam board, thin and covered with cloth. Sound will travel easily through them. A handy thing if one wants to listen in on the conversations of one’s fellow passengers.

Where would it be? He tips his head to the side, pensive. Not in the closet. A quick search finds no hidden panels or packages. Neither is it in the mattress, pillowcases, or any of the bedding. The cabinets above and below the sink are empty, as is the light fixture attached to the ceiling. The American wonders for a brief moment if his request has been refused. He dismisses the idea out of hand. His requests are never refused. There is only one place in the room he has not checked, and he immediately feels a sense of disappointment. He thought the officer would have more imagination. Apparently not. He finds what he’s looking for beneath the berth in the farthest, darkest corner: an olive-green military-issue canvas bag. He is pleased with the contents.

A note, folded in half, with three words scrawled in black ink by a hasty hand: Make it clean.

A dog tag strung on a rusted ball chain, once belonging to the man he has come to kill. And a pistol, a Luger with a fully loaded cartridge. But there is no name. He was promised a name. He lifts the tag and inspects the information stamped on its surface. They expect him to decipher this clue on his own. They have baited him.

The American slides the bag under his pillow and stretches out on the bed, his arms beneath his head. He’s still lying there ten minutes later when the steward returns with his suitcases. They are tucked beneath the bed and once again he is alone. But not asleep. He is thinking about what he must do next. He is thinking about the mailroom and how he will get inside unnoticed before they reach Cologne later tonight. He is thinking about the letter that has to be delivered. The American creates a mental inventory of each action that needs to be taken over the next three days and how everything—absolutely everything—must go according to plan.

The Cabin Boy

Werner Franz will not let them see him cry. He has smashed his knee into the edge of a large steamer trunk and the pain is so sharp and deep inside the bone that he can feel a howl building in his chest and he clamps his teeth shut so it won’t come bellowing out. If he were at home or at school or anywhere but here with these men, he would allow himself the luxury of sobbing. But he will not prove himself a baby in front of his fellow crew members. He already takes enough ribbing as it is. So Werner steps aside and closes his eyes. Men pass him carrying trunks and luggage. He hears the shuffling of feet and the bark of a dog and a muttered curse, and he counts to ten silently, trying to compose himself. He lets out a long, deep breath, his scream subdued into silence, but he can’t help glaring at the trunk. It’s none the worse for wear, but he’ll be bruised for weeks.

Werner spins around when a large hand grips his shoulder. He looks directly into a broad barrel chest, then up into the face of Ludwig Knorr. The man is a legend on this ship, and Werner is in awe of him. But it’s the sort of awe that leads him to scuttle out of a room when Knorr enters, or to press himself against the corridor wall when they pass one another. A sort of reverence turned to abject terror, even though the man has never so much as spoken to him. Until now.

“If you’re going to kick something,” Knorr says, his voice a low rumble, “make sure it’s the door and not that trunk.” He points at the letters lv stamped in gold filigree across the leather. “It costs more than you’ll make all year. Understand?”

Werner nods his head. Drops his eyes. “Yes, Herr Knorr.”

Ludwig ruffles his hair. “And steer clear of Kubis for a while. He’s in a rage today. It’s the dogs. He hates dogs.”

Heinrich Kubis checks the tag on the trunk next to Werner. Then he orders one of the riggers to take it to the cargo area instead of to the passenger quarters. He ticks a box on the clipboard in his hand and moves on to the next item. Beside Kubis is a large provisioning hatch that opens onto the tarmac below, where a pile of luggage is waiting to be lifted into the ship. The tricky part is determining whether the items go to the cabins or the cargo area. Kubis is unruffled, however, and gives orders without the slightest hesitation.

There is a frantic scrambling and clanging as the dogs are raised on the cargo platform. They spin and bark and whimper, making their wicker crates rattle. Werner knows the poor little beasts are terrified, but Kubis shows no sympathy. “To the cargo hold,” he orders, and the cages are lifted by two riggers apiece and carted away through the cavernous interior of the ship.

“I will never understand,” Kubis mutters, “why these fools insist on traveling with their pets.”

After ten more minutes of Kubis griping about live cargo, all the luggage has been dispersed except for one leather satchel. This he hands to Werner. “Stateroom nine on B-deck. Set it neatly on the bed so Frau Adelt will see it upon entering. She is, apparently, quite particular about her things.”

Werner takes the satchel and heads toward the passenger area. He is as familiar with the layout of this ship as he is with his parents’ apartment in Frankfurt. He turns the corner near the gangway stairs a bit too fast, almost knocking a young woman to the ground. But she has great reflexes and an even better sense of humor. She dances out of the way with a smile.

“I’m so sorry, Fräulein.” Werner blushes.

She ignores the apology. “Have you seen my brother?”

Werner is typically quick on his feet and quite affable. But this girl is very pretty. And she looks to be about his age. She’s staring at him, waiting for an answer to her question. He can’t seem to remember what she asked, so he stands there with the satchel clutched stupidly to his chest.

“My brother?” she asks again. “Have you seen him? He’s eight and blond and I’m going to wring his neck when I find him. Mama is in a state looking for him.”

“No.” Werner clears his throat so his voice won’t crack. “I’ve not seen him.”

“Well, if you come across the little imp, would you send him to the observation deck?”

“Of course. What is his name?”

“Werner.”

“That is my name also.” He almost doesn’t ask. It isn’t technically appropriate. But the question is out before he can reel it back in. “What is yours?”

Her eyes widen a bit, but in surprise, he thinks, not objection. “Irene.”

He’s careful to give her a small subservient nod. “Nice to meet you.”

Irene almost says something to this—her lips are parted slightly as though to reply—but she appears to change her mind. She pauses for a moment, then flounces off without another word. But when she turns to go up the stairs to A-deck, Werner can see a smile playing at the corners of her mouth, and she betrays herself by giving him a quick backward glance before she disappears. He stands there, watching her go, wondering why he wishes she would come back and make some other impertinent remark about her brother.

It has been almost two years since Werner was in school, and just as long since he has spent any significant amount of time around girls. So he is surprised by the heat in his cheeks and the smile on his face. He does not know what to make of the flipping in his stomach. Werner cannot identify the subtle shift that takes place within him as he carries the satchel through the open door and into the Adelts’ stateroom. He places it carefully beside the pillow. It feels as though the wires in his mind have come alive all at once in a sudden rush of electrical current. There is a buzzing in his head. He knows what it’s like to be afraid and to be exhausted and to be hungry, and even though this feels like a combination of all three, he is aware that it is something different. Something unique. Werner Franz makes his way to the observation deck to join the rest of the stewards, experiencing something very new indeed.

The Stewardess

The promenade on A-deck is filled with passengers leaning over the slanted observation windows when Emilie enters, holding the hand of a tear-stained young boy who has lost his mother. She squats down next to him, his hand nestled in her palm, and points at a short, capable-looking woman who is stretched onto her tiptoes to see over the shoulders of the man in front of her. “See, there she is. I told you we wouldn’t leave without her.”

Matilde Doehner. Emilie pronounces the woman’s name to herself three times—once in German, once in English, and once in Italian—to set the face in her mind. It had taken poor little Werner two minutes of rattled sobs to stutter her name. He’d managed to say his own name with a teakettle screech and a fresh batch of tears.

The child is eight years old and clinging to the last remnants of little boyhood. He pulls his hand from Emilie’s, wipes his sleeve across his nose, then takes a deep breath that bears an uncanny resemblance to a hiccup. “Please don’t tell my brother I cried. He’ll think I’m a baby.”

His little face is so earnest, so fearful that she has to suppress a laugh. “I won’t say a word. I promise.”

Werner’s brother—Walter, she notes, again mentally, repeating the name in every language she knows—stands next to their mother, back turned. The bottom of one pant leg is tucked into his sock, and his shoes are unlaced. Emilie is certain that when push comes to shove—which it certainly will, they are boys after all—little Werner will be able to hold his own. “Off you go,” she says, then gently nudges him toward his mother.

He squares his shoulders and joins his family as they jostle for position in front of the windows. He announces his arrival by giving Walter a pre-emptive elbow in the ribs. I’m here, that elbow says, and I’m not afraid of you. Emilie fights the ache she feels at the good-natured tussle.

“Neatly done, Fräulein Imhof.”

It takes her one beat too long to recognize Colonel Fritz Erdmann. He’s wearing civilian clothes instead of his Luftwaffe uniform. He hasn’t shaved. And he looks haggard.

“Colonel Erdmann”—she dips her head slightly in respect—“how can I help you?”

Erdmann motions her to step aside with him. He lowers his head and his voice. “I need you to page my wife.”

“But we’re about to cast off—”

“Bring her to me. I need to say good-bye.”

Erdmann has a strong Germanic brow ridge and bright, curious eyes. Emilie feels very much as though she’s being skewered by his gaze. And she would like to ask if there is someone else who can perform this errand—she is in the middle of her duties, after all—but the look on Colonel Erdmann’s face brooks no argument.

“Of course,” she says. “Where should I bring her?”

He looks around the promenade as though the question has rendered him helpless. It seems as though every passenger is crowded around the windows pointing, laughing, eager. “Here will be fine, I suppose.”

Emilie takes the stairs two at a time down to B-deck. She’s not entirely certain there is time to fulfill Colonel Erdmann’s request, although she does note that the ground crew has not raised the gangway stairs.

Willy Speck and Herbert Dowe startle when Emilie throws the door back and steps into the radio room. They look at her as though she has materialized naked right in front of them, as though they’ve never seen a woman before. Both men are at their stations, headphones on, fingers hovering over a board filled with knobs and levers as they await orders for liftoff.

“You can’t be in here,” Willy says. The lame protest seems to be the only speech he’s capable of, for he falls silent afterward.

“Yes I can.” Emilie has never taken kindly to being told what she can and cannot do. Certainly not by a gap-toothed radioman with hygiene issues.

“But you’re a . . . woman,” he adds lamely.

“I’m a crew member. Same as you. With full access to the ship. Same as you. I also happen to be performing my duties, namely having a family member of one of our premier passengers paged to come aboard the ship. Excuse me,” she says, pushing past the still- silent-therefore-clearly-more-intelligent Herbert Dowe and descending a ladder into the control car below. Her uniform makes the job delicate, but she’s too angry now to care. If anyone below is peering up her skirt, let them see her garter belt, and her acrimony. But the officers below are gentlemen. They keep their eyes lowered until she has planted both feet firmly on the carpeted floor of the utility room.

Emilie meets the questioning glances of Commander Pruss and his crew without hesitation. “I’m sorry to interrupt your flight preparations, Commander, but Colonel Erdmann requested that I page his wife.”

“Why?”

She doesn’t intend to lie; the words simply form in her mouth before she has time to think about them. “He didn’t say. But he’s quite insistent.”

The colonel said he wanted to tell his wife good-bye. That’s what she’s thinking while Pruss mulls the request. It was the strangled note in Erdmann’s voice at the word good-bye that has Emilie lying so easily now. Her own husband never had the chance to say good-bye before he left her for good. Her fingers twitch, wanting to reach up and find the key that hangs between her breasts, the key that her husband gave her on their wedding night.

One of the things that puzzles Emilie most about Max Zabel is his timing. He finds her, always, in these moments when she is vulnerable. Emilie does not want to be rescued, and yet there he is. Max descends the ladder into the control car and steps forward to stand between her and Commander Pruss. The gesture is not so much protective as authoritative, as though he’s certain that whatever the trouble might be he can resolve it.

“Is something wrong?” Max asks.

Emilie finds herself the object of Max’s curious gaze. It is alarming, that gaze, how it can root her to the floor. How it can wipe her mind clean of every thought, every objection. How it can make her forget even her late husband. This is why she resists Max, why she hates him at times. Emilie does not want to forget.

They both look to Pruss for an answer.

“No,” the commander says, but does not elaborate. Instead he stares at Emilie as though he is seeing her for the first time.

Many years of service aboard ocean liners and her tenure aboard the airship have taught Emilie that important men do not like to be pressed for time, answers, or decisions. Benevolence, although often required, is something they bestow on their own terms. In their own way. So she stands with her fingers laced in front of her, her face set pleasantly in expectation, her lips pressed together with the barest hint of a patient smile. Hurry, hurry, she thinks. I’m the one who will have to serve Colonel Erdmann for the next three days, not you. If Pruss refuses the colonel’s request there is nothing she will be able to do about it. He is commander, after all, but she will be required to deliver the news.

“Max,” Pruss finally orders, “get the bullhorn and instruct the ground crew to have Dorothea Erdmann brought up from the other hangar.” He turns to Emilie. “You will collect her, I presume?”

“Yes, Commander.”

Max gives Pruss a sharp, obedient nod and steps around a glass wall into the navigation room. She has never seen him in this environment before; she has been in the control car only one time—during her initial tour of the airship. Seeing Max surrounded by his charts and navigational equipment makes sense. Another little piece of the puzzle locks into place. He is a mystery that is slowly, consistently being solved.

“Is there anything else, Fräulein Imhof?” There’s the trace of humor in Commander Pruss’s voice.

She’s staring at Max. Damn it, she thinks. Everyone has noticed. They’ll pick him apart for that. “No,” she answers.

“You may return to your duties, then.”

Emilie hears a distorted version of Max’s deep voice echoing through the bullhorn as she ascends the ladder. The pointed look she gives the radiomen is very much an I-told-you-so rebuke. Once the door is shut behind her she stops to compose herself.

The only jewelry that Emilie wears is a skeleton key on a silver chain around her neck. The chain is long and tucked beneath her dress, hidden from view. She has not taken it off in the years since Hans died, and the side that lies against her skin has grown tarnished. It feels warm and heavy now, like a weight against her heart, so she pulls it out and cradles the key in her palm. It is the only thing she has left of her old life.

It is a life worth remembering, and Emilie struggles to keep Max Zabel from invading it. She tucks the key back inside her uniform, squares her shoulders, and goes to the gangway stairs to collect Dorothea Erdmann.

The Journalist

Who is that woman, do you think?” Gertrud sets a slender fingertip against the window and points at a military jeep speeding across the tarmac toward them. A woman sits in the front seat, her hair blowing wildly around her face while she holds on to the door with one hand.

“She was on the bus. I saw her,” Leonhard says.

“Is she a passenger?”

“Apparently not.”

The jeep parks directly below them, out of sight, and a few moments later the woman rushes into the promenade, followed closely by the stewardess, and throws herself into the arms of a man standing apart from the rest of the passengers. Some turn to watch the spectacle, but most seem oblivious, their attention held by the pre-flight operations below.

The moment the couple embraces, the stewardess backs away, leaving the room looking pale and unsettled. Gertrud puzzles at this as they embrace each other, as tight as two humans can, for well over a minute.

“You know,” Leonhard whispers, “I’ve never seen a guest brought on board this close to takeoff before. They’re quite serious about security. It’s likely that only his rank made it possible.”

The man’s clothing is indistinguishable from that of the other civilian passengers, and Gertrud gives her husband a questioning glance. “Who is he?”

“Fritz Erdmann.”

“You know him?”

“He’s a Luftwaffe colonel. Kommandant at the Military Signal Communications School. He was appointed as a military observer to the Hindenburg earlier this year. It’s not something he’s thrilled about.”

“You know this because . . . ?”

“He told me. During the first commercial flight to Rio de Janeiro in March.”

Of course Leonhard would know this. Leonhard knows everything about Germany’s airship program. It is this knowledge, and his journalism skills, that have them on this ridiculous flight to begin with. He has recently collaborated on the autobiography of Captain Ernst Lehmann, director of flight operations for the Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei. This flight was provided gratis so Leonhard could meet with his U.S. publishers prior to the book’s release next month. Gertrud’s attendance, though unwilling, was required as well.

Colonel Erdmann and his wife finally separate and stand gazing at one another. He brushes his thumb along her cheekbone, perhaps to wipe away a tear—Gertrud cannot be certain—and then she steps away from him and quietly leaves the ship. It occurs to Gertrud as she watches the jeep carry Frau Erdmann back to the hangar that neither of them uttered a word the entire time.

The colonel looks despondent as he watches his wife leave, and Gertrud smells a story. She sets her hand on Leonhard’s arm. “Darling,” she says, “I think that man needs a drink.”

Leonhard gives her the look, the one that says he recognizes the purr in her voice, and that he knows she’s up to something, but she’s just too damn clever for him to preempt whatever mischief she has planned. He won’t try to stop her, though. He never does.

“You will behave yourself?” He takes a step toward the door.

“Where are you going?”

“To the bar.”

“Why? The stewards are passing out champagne.”

He clucks his tongue. “Liebchen, champagne is not going to give you what you’re after.”

“Who says I’m after anything?”

“I would be highly disappointed if you weren’t.”

This is why Gertrud married a widower twenty-two years her senior. Leonhard is the only man she has ever met who not only appreciates her gumption but encourages it. “Well, then, order the good colonel a Maybach 12 and one for me as well.”

“Careful, Liebchen.Alte Füchse gehen schwer in die Falle.”

She laughs and pats his cheek. “He’s not such an old fox as that. Younger than you by the looks of it. And my traps are well laid.”

Leonhard lifts her hand and turns it palm up. He kisses it lightly. “I cannot argue that.” He dips his mouth toward her ear. “Many things about you are well laid, Liebchen. Though I prefer that you not spread such tempting traps for him as you did for me.”

“I hardly doubt you’ll be gone long enough for that.”

“If it’s the Maybach 12 you’re drinking tonight, you’ll not have much time yourself before I’ll have to carry you to bed.”

“You’ll hardly get the chance if you never get the drinks.”

“Start slowly at least. You don’t have the legs to hold much of that particular drink.” Leonhard leaves her then and goes in search of the bar on B-deck and its famous cocktail, the recipe for which is known only to the bar steward, a secret that is guarded more closely than the Hindenburg itself.