Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

FROM THE BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF THE FROZEN RIVER 'Told with masterful intensity and moments of true human compassion' Helen Simonson, New York Times bestselling author of The Summer Before the War 'Inspired by history, and infused with imagination and intrigue, this novel satisfies with every twist and turn' Patti Callahan Henry, New York Times bestselling author of Becoming Mrs. Lewis 'A gorgeous, haunting puzzle of a book that will grip you until the final page' Abbott Kahler, New York Times bestselling author of Sin in the Second City In an enthralling new feat of historical suspense, Ariel Lawhon unravels the extraordinary twists and turns in Anna Anderson's 50 year battle to be recognized as Anastasia Romanov. Is she the Russian Grand Duchess, a beloved daughter and revered icon, or is she an imposter, the thief of another woman's legacy? Countless others have rendered their verdict. Now it is your turn. Russia, July 17, 1918: Under direct orders from Vladimir Lenin, Bolshevik secret police force Anastasia Romanov, along with the entire imperial family, into a damp basement in Siberia, where they face a merciless firing squad. None survive. At least that is what the executioners have always claimed. Germany, February 17, 1920: A young woman bearing an uncanny resemblance to Anastasia Romanov is pulled shivering and senseless from a canal. Refusing to explain her presence in the freezing water or even acknowledge her rescuers, she is taken to the hospital where an examination reveals that her body is riddled with countless horrific scars. When she finally does speak, this frightened, mysterious young woman claims to be the Russian grand duchess. As rumours begin to circulate through European society that the youngest Romanov daughter has survived the massacre at Ekaterinburg, old enemies and new threats are awakened. The question of who Anna Anderson is and what actually happened to Anastasia Romanov spans fifty years and touches three continents. This thrilling saga is every bit as moving and momentous as it is harrowing and twisted. FIVE STAR RAVE READER REVIEWS - 'Oh! What a perfect ending!' - 'The best Romanov story I have ever read' - 'Fascinating, intriguing and very hard to put down! ... Spellbinding from start to finish' - 'WOW! Just, a 5+ stars WOW!' - 'You will be enraptured' - 'It's going to break your heart' - 'A truly remarkable book'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 588

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

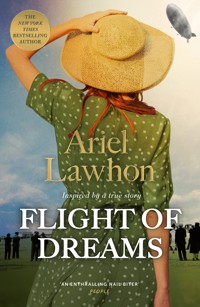

Also by Ariel Lawhon

The Frozen RiverFlight of DreamsThe Wife, the Maid, and the Mistress

As always, for my husband, Ashley, because I would be lost without him.Also, for Marybeth because she gave me the title.And for Melissa: editor, champion, and friend.

If history were taught in the form of stories, it would never be forgotten.

—Rudyard Kipling, The Collected Works

Fair Warning

If I tell you what happened that night in Ekaterinburg I will have to unwind my memory—all the twisted coils—and lay it in your palm. It will be the gift and the curse I bestow upon you. A confession for which you may never forgive me. Are you ready for that? Can you hold this truth in your hand and not crush it like the rest of them? Because I do not think you can. I do not think you are brave enough. But, like so many others through the years, you have asked:

Am I truly Anastasia Romanov? A beloved daughter. A revered icon. A Russian grand duchess.

Or am I an impostor? A fraud. A liar. The thief of another woman’s legacy.

That is for you to decide, of course. Countless others have rendered their verdict. Now it is your turn. But if you want the truth, you must pay attention. Do not daydream or drift off. Do not speak or interrupt. You will have your answers. But first you must understand why the years have brought me to this point and why such loss has made the journey necessary. When I am finished, and only then, will you have the right to tell me who I am.

Are you ready? Good.

Let us begin.

Part One

The End and the Beginning

Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.

—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

1

Anna

Folie À Deux

1970, 1968

Charlottesville, VirginiaFebruary 17, 1970

Fifty years ago tonight Anna threw herself off a bridge in Berlin. It wasn’t her first brush with death, or even the most violent, but it was the only one that came at her hands. Anna’s husband does not know this, however. She watches him, watching her, and she knows he sees only a fragile old woman who has waited too long for vindication. He sees the carefully cultivated image she presents to the world: a crown of thinning silver hair and tired blue eyes. Age and confusion and a gentle aura of helplessness. This impression could not be further from the truth. She has been many things through the years, but helpless is not one of them. At the moment, however, Anna is simply impatient. She sits in this living room, two thousand miles from her past, waiting for a verdict.

Jack is like a frightened rabbit, all nerves and tension. He springs from his chair and begins to pace through the cluttered den. “Why haven’t they called? They should have called by now.”

“I’m sure they read the verdict hours ago,” Anna says, leaning her head against the fold of her wingback chair and closing her eyes.

Whatever news awaits them is not good, but Anna does not have the heart to tell him this. Jack is so hopeful. He has already written a press release and taken a Polaroid so he can bring both to The Daily Progress first thing in the morning. Jack spoke with the editor this afternoon, suggesting they reserve a front-page spot for the story. He’s hoping for something above the fold. He’s hoping for exclamation points.

Even though Jack hasn’t admitted it, Anna knows that he is looking forward to reporters showing up again. They haven’t had any in months, and she suspects he’s gotten lonely with only her and the animals for company. She feels a bit sorry for him, being saddled with her like this. But there was no other way. Gleb insisted on it, and in all the years she knew him, Gleb Botkin remained her truest friend, her staunchest champion. He’s been dead two years now. Another loss in an unending string of losses. Jack is kind to her—just as Gleb promised—and beggars can’t be choosers anyway. Anna reminds herself of this daily.

The phone rings. Three startling metallic alarms and then Jack snatches it from the cradle.

“Manahan residence.” A pause, and then, “Yes, she’s here. Hold on a moment.” The cord won’t stretch across the room, so Jack lays the receiver on the sideboard. He grins. “It’s from Germany.”

“Who?”

“The Prince.” He beams, then clarifies—there have been a number of princes in her life. “Frederick.”

Anna feels a wild stab of anger at the name. She hasn’t forgotten what Frederick did, hasn’t forgotten the burn pile behind her cottage at the edge of the Black Forest. All those charred little bones. If the news had come from anyone else she would take the call. “I don’t want to speak with him.”

“But—”

“He knows why.”

“I really think it’s time you—”

Anna holds her hand up, palm out, a firm, final sort of motion. “Take a message.”

Jack pouts but doesn’t protest. He knows that arguing is futile. Anna does not change her mind. Nor does she forgive. He picks up the receiver again. “I’m sorry. She doesn’t want to speak right now. Why don’t you give me the news?”

And then she watches Jack’s countenance fall by tiny, heartbreaking increments. First his smile. Then his lifted, expectant brows. His right arm drops to his side. He is deflated. “I don’t understand,” he says, finally, then clears his throat as though he has swallowed a cobweb.

“Write it down,” Anna instructs. “Word for word.” She doesn’t want to interpret the verdict through his anger once he hangs up. Anna wants to know exactly what the appeals court has to say. Jack is too emotional and prone to exaggeration. He needs to transcribe the decision in its entirety or vital bits of information will be lost the moment he hangs up. Gleb wouldn’t need this instruction. He would know what to do. He would know what questions to ask. But Gleb is no longer here, and, once again, this reality leaves her feeling adrift.

“Let me write this down,” Jack says, like it’s his idea. She watches him shuffle through piles of paper on the cluttered sideboard, looking for a notebook with blank pages. Finding none, he grabs an envelope and turns it over. “Go ahead. I’m ready.”

A decade ago Anna’s lawyer told her this lawsuit was the longest-running case in German history. This appeal has stretched it into something worse, something interminable. And there stands Jack, writing the footnote to her quest on the back of their electric bill in his tidy, ever-legible script. “How do you spell that?” he asks at one point, holding the phone with one hand and recording the verdict with the other. He doesn’t rush or scribble but pens each word with painstaking precision, occasionally asking Frederick to repeat himself.

Jack and Anna don’t have many friends. They haven’t been married long, only two years, and theirs is a relationship based on convenience and necessity, not romance. They are old and eccentric and not fit for polite society in this quaint college town. But a handful of people—mostly former professors at the University of Virginia, like Jack—are due to arrive shortly. Anna doesn’t want to know how he convinced them to come. Entertaining would have been awkward if the decision had gone in her favor. It will be excruciating now. Anna decides there won’t be a party tonight. She doesn’t have the heart to entertain strangers this evening.

But Jack, in all his eagerness, has cooked for a celebration. Their small den is littered with trays of fruit and sandwiches. Deviled eggs and cheese platters. Tiny brined pickles and cocktail sausages skewered with toothpicks. He even bought three bottles of champagne that sit in a bowl of ice, unopened beneath the string of Christmas lights he stapled to the ceiling. Anna stares at the bottles with suspicion. She hasn’t touched the stuff in almost four decades. The last time Anna drank champagne she ended up naked on a rooftop in New York City.

The entire setting is tacky and festive—just like her husband. Jack bought a rhinestone tiara from the costume shop near the college campus just for the occasion. It sits on a gaudy red velvet pillow next to the champagne. He’s been dying to crown her since they met, and only today, only in the hopes of a positive verdict, has she humored him. But that hope is gone now. Snuffed out in a German courtroom on the other side of the world.

“Thank you,” he finally says, and then lower, almost a whisper, “I will. I’m sorry. You know how she can be. I’m sure she’ll speak with you next time. Good-bye.”

When he turns back to Anna, Jack has the envelope pressed to his chest. He doesn’t speak.

“We need to call our guests and tell them the party’s canceled,” she says.

He looks crushed. “I’m so sorry.”

“This isn’t your fault. You did what you could.” A shrug. A deep breath. “What did Frederick say?”

“Your appeal was rejected. They won’t reverse the lower court’s ruling.”

“I gathered that. Tell me his words exactly.”

Jack looks to the paper. “They regard your claim as ‘non liquet.’ ”

“Interesting.”

“What does that mean?”

“ ‘Not clear’ or ‘not proven.’ ”

When Jack frowns, he puckers his mouth until his upper lip nearly touches his nose. It’s an odd, childish expression and one he’s used with greater frequency the longer he has known her. “Is that German?”

“Latin.”

“You know Latin?”

“Very little at this point.” Anna swats at him. “Go on.”

“The judges said that even though your death has never been proven, neither has your escape.”

“Ah. Clever.” She smiles at this dilemma. It is the ultimate Catch22. Her escape can’t be proven without a formal declaration of identity from the court. “Read the rest please.”

Jack holds the envelope six inches from his nose and slowly recites the verdict. “ ‘We have not decided that the plaintiff is not Grand Duchess Anastasia, but only that the Hamburg court made its decision without legal mistakes and without procedural errors.’ ” He looks up. “So they have decided . . . nothing?”

She shakes her head slowly and then with more determination. “Oh, they have decided everything.”

“It was that photo, wasn’t it? The court must have seen it. There’s no other reason they would rule against you. Damn that Rasputin. Damn her!” Jack begins to pace again. “We could make a statement—”

“No. It’s over.” Anna lifts her chin with all the dignity she can muster and folds her hands in her lap. She is resigned and regal. “They will never formally recognize me as Anastasia Romanov.”

Two Years Earlier

Charlottesville, VirginiaDecember 23, 1968

Anna does not want to marry Jack Manahan. She would rather marry Gleb. Even after all the trouble he has caused through the years. But theirs is a story of false starts and near misses. Bad timing. Distance. And rash decisions. They were not meant to be. So Gleb has urged her to marry Jack instead. This whole fiasco is his idea—the courthouse, the silly pink dress, the bouquet of roses and pine cones, the white rabbit-fur hat that she’s supposed to wear out of the courthouse to greet the photographers (these arranged by Jack because the damnable man cannot help but make a scene everywhere he goes). Gleb insists the hat makes her look the part of a Russian grand duchess. She refuses to wear the thing. Poor rabbit.

When they discussed this ridiculous plan in August, Gleb said his health was to blame. He couldn’t marry her himself because she would end up having to take care of him. Anna believes that this is punishment for a long-held resentment. Tit for tat. Wound for wound. He has loved her for decades, and she has never been able to fully reciprocate. Now he stands as witness to her unwilling nuptials. As best man, in fact.

It is snowing outside the courthouse. Not the angry, hard, blistering shards of snow she is used to in Germany, but fat, lethargic flakes that drift and flutter and take their time getting to the ground. Lazy snow. American snow.

Anna’s had only a single tryst since that limpid summer in Bavaria all those years ago, but Gleb moved on. Got married. Had children. They’ve never talked about the intervening years, and it’s not worth bringing up now. Anna is in her seventies—too old to get married at all, much less for the first time. Jack Manahan is twenty years her junior. A former professor enamored with Russian history, and with her—or, at least, the idea of her. Regardless, he hasn’t put up much of a fight since being presented with the plan. Jack’s only show of hesitation was a long, curious look at Gleb. Assessing his attachment and willingness to let Anna go.

It occurred to her, far too late in the process, that she had not considered the issue of sex. Jack is young. Younger at least. And she is . . . well . . . she is not. The idea of consummation almost caused her to back out of this arrangement entirely. All of those hormones have shriveled up, turned to dust, and blown away. Desire is little more than a fond memory these days.

Gleb has taken care of that issue as well, however, assuring her that sex isn’t a necessary part of this bargain. She and Jack will have separate bedrooms. This will be a legal marriage, enough to keep her in the United States once her visa expires in three weeks, but it will be a marriage of convenience only. Gleb swore this, endless times, over their last shared bottle of wine. Jack will not lay a hand on her. Unless she wants him to. Why Gleb added that last part she isn’t sure. He wouldn’t meet her eyes as he said it, and she did not reply. It was a small cruelty. This is how it is with them, apparently. Little wounds. Paper cuts. Just enough to sting but not really harm. Perhaps it’s best that they aren’t marrying each other after all.

Gleb slips into the antechamber beside the courtroom and surveys her tiny, slender form. “You look nice.”

He seems weary and pale and infirm. He’s lost weight recently, and his once broad shoulders have narrowed with illness and age. Anna wants to ask Gleb if his heart has gotten worse. But she’s afraid of what his answer might be. So she says, “I look ridiculous.”

“All brides look ridiculous. That’s why they’re so charming.”

Anna turns back to the window. It’s late afternoon, getting darker by the moment, and the overhead light bounces off the glass, throwing her reflection back at her. She touches a hand to her cheek. Traces one deep wrinkle after another, each of them telling a story she’s long since decided to forget.

“I am too old for this,” she says.

“I know.”

“You admit it then?” She studies his reflection too, hovering over her shoulder. “But no apology, I see.”

“It is this or you return to Germany,” he says. “We are out of time.”

“That always seems to be the case with us, doesn’t it?”

“Ships in the night,” he whispers and sets a large, warm hand on her shoulder. “Are you ready? Sergeant Pace is waiting. So is Jack.”

“Sergeant?”

“Judge Morris called in sick this morning.”

Anna turns to him and looks, not at his face, but at the knot in his tie. She stares at the red and blue alternating stripes on the fabric, those thin lines circling back on themselves, all twisted and turned around. Anna is knotted up as well, but now, suddenly, it’s with mirth.

“I am to be married,” she asks, tilting her chin to meet those twinkling green eyes, “not by a priest, or a judge, but by a police officer?”

“It gives an entirely new meaning to being read your rights, doesn’t it?”

They laugh, then, long and loud. She turns back to the window and they stand in comfortable silence, watching Charlottesville disappear beneath the snow.

Finally Anna leans her head back against Gleb’s chest. “How did I get here?” Anna sighs, already knowing the answer. She has gotten here, she has survived, by always doing the thing that needs to be done.

Four Months Earlier

Charlottesville, VirginiaAugust 20, 1968

Virginia in August feels very much to Anna as though she has taken up residence directly in the white-hot center of Satan’s armpit. She has never known such heat. Nor has the word humidity meant anything at all prior to her arrival in the United States. And yet here she sits, on Jack Manahan’s front patio drinking tea—with ice, no less—and melting into her rocking chair as they talk about nothing in particular.

Anna fans her face with an old magazine—something about gardens and guns—wishing the sun would slide down the horizon a little more quickly. “How can you live like this?”

Jack peers at her over the top of a glass that is beaded with sweat. “Like what?”

“Like a potato put in the oven to roast. It’s intolerable.”

“This is August,” he says as though that explains everything. He’s wearing trousers, long sleeves, and a gaudy checkered tie cinched up tight to his Adam’s apple. He doesn’t seem the least bit uncomfortable. “I hardly notice it anymore.”

It is a distinctly American thing, Anna thinks, to have an entire conversation about the weather. They have been sitting on this patio for the better part of two hours waiting for Gleb. He’s off running some errand in town and has promised to return by dinner. So far they have discussed variations in climate along the Eastern Seaboard of the United States, rain patterns in the Midwest, and a damaging drought in California that is threatening almond growers. The man is absurdly pleased by the sound of his own voice, needing very little encouragement from her. A simple hum or murmur is enough to launch him into another monologue. Anna wonders how much more she can tolerate before crawling out of her skin when a long, sleek, black car enters University Circle and approaches the house. It’s the kind of vehicle that smacks of importance and a need to be seen.

“Who is that?” Jack asks as the car pulls into the driveway and parks behind his station wagon.

“I’m not sure.” Anna tries not to feel guilty about the lie. She has an unwelcome suspicion about who this visitor might be.

“They look very determined.” Jack leans forward, taking in the women who spring from the car and march up the sidewalk toward them.

“Anastasia!” shouts the older of the two as she reaches the bottom of the steps. The look on her face is one of alarming enthusiasm.

This woman is Russian. This woman is dangerous.

She mounts the stairs with an energy and aggression that Anna lost years ago. Following two steps behind her and watching cautiously is the woman’s companion. She has coiffed hair, lips painted red, and eyes framed by black designer glasses. In one hand she carries a notepad and in the other a tape recorder. A reporter. Anna stiffens in her seat.

And then the first woman is in front of Anna, chatting and bending at the waist—not quite a bow but an allusion to one. Anna shrinks away as she confirms the familiar face and the deep, throaty voice. The dark hair—dyed now, she thinks; there’s not a strand of gray—and sharp eyes. The angular nose. The sly mouth. The large body shaped like a concrete block. The woman grabs her hand and shakes it with vigor. Anna fears being yanked out of her chair and forced into a hug.

The thing Anna has always hated most about being a small woman is the disadvantage she has in situations like this. People assume they can touch you, pat you, shake your hand without permission. They assume that if your size is little more than that of a child, you must be one. That you can be talked down to or coerced. It is hard for a small person to be intimidating or to be taken seriously. This lack of stature has forced Anna to develop other skills through the years: to sharpen her wit, to treat her tongue like a blade and her mind like a whetstone.

“I am not a rag doll. You needn’t shake me like one. Or touch me at all for that matter,” she says.

“I’m sorry,” the other woman says, stepping forward. “We have failed to introduce ourselves. I am Patricia Barham but please, call me Patte—”

“I have no interest in speaking with reporters today.”

Patte looks at the objects in her hands and then tucks both behind her back, as though she’d forgotten they were there and is suddenly ashamed of them. “I’m not a reporter, at least not in the traditional sense. I’m a biographer.” She tips her head toward her friend. “And of course you remember Maria Rasputin. As she tells it, the two of you have known each other since childhood.”

“Rasputin?” The name has Jack’s full attention and he sits ramrod straight in his chair. “As in relation to Grigory? The heretic monk?”

“Not a monk,” Maria says, “as is evidenced by my existence. The heretic label is, of course, open to interpretation.” She has the pinched look of a woman who is tired of defending the indefensible.

Anna has yet to rise from her seat or offer one to their uninvited guests. She is wary of Maria Rasputin and for good reason.

The melodramatic rise and fall of Maria’s voice makes it sound as though she’s in a stage production. Anna doesn’t like the grand, sweeping gestures she makes with her arms or the aggressive way she smiles. Those small white teeth that snap and flash. But it is her eyes that disturb Anna most. They are a bright—almost unnatural—blue. Piercing, but not in a way that compels someone to come closer. Anna finds herself wanting to turn away and hide from that penetrating gaze. She shouldn’t be surprised. Grigory Rasputin was known to have those same terrifying, hypnotic eyes. Like father, like daughter.

But Maria’s stare is hard to escape, and she moves closer, nearly leaning over Anna’s chair.

“Yes,” she says, as though finally coming to some long-awaited conclusion. “There’s something about her.” Again, waving that arm in a grandiose manner. “A certain nobility. It’s there in her demeanor. In her voice.” Maria nods sharply. “I believe this to be Anastasia Romanov.”

“What do you want?” Anna presses her palms against her knees so she won’t strike that self-satisfied grin from Maria’s face.

“Only to visit with an old friend—”

“We thought, perhaps, that we could take you to dinner,” Patte interrupts. She has tucked the notepad and recorder into her purse, and her hands now hang free and nonthreatening at her sides.

Jack perks up at the mention of food. “Dinner with friends could be fun. There’s a wonderful Italian restaurant not too far from here.”

“You came all the way here—where did you say you came from . . . ?” Anna asks.

“I didn’t. But New York, since you’re curious.”

“All the way from New York just to have dinner?”

“Dinner, yes.” And it’s here that Maria shows her cards because she cannot keep the devilish smile at bay. “But I’ve also got a proposition for you.”

————

“I am not going to Hollywood.” Anna sets her fork down.

Jack taped a note to the front door when they left with Maria and Patte Barham, telling Gleb that they’d be at Salvio’s, but he’s yet to join them and Anna looks to the door every few moments. This was a mistake. She and Jack are a captive audience for these women and their ludicrous plan. She regrets consenting to have dinner with them.

“Don’t be so hasty,” Patte says. “There’s a lot of money to be made.”

“My story is not for sale.”

Patte doesn’t say it, but her Cheshire cat smile suggests that she believes everyone’s story is for sale. She shrugs. Spears a piece of mushroom. Swallows it without chewing. “People are curious. They want to know what it was like. They want to know how you survived. There’s nothing wrong with supporting yourself in the process.” She looks at Anna’s simple cotton dress, frayed at the collar, faded by too many turns through the wash, and lets her gaze linger just long enough to declare that she knows Anna needs the money. And then, to drive the point home, she adjusts the chain of an expensive gold necklace draped around her own neck.

Anna pushes her plate away. “I would like to go home.”

“And where, exactly, is home?” Maria Rasputin asks.

“I am staying with Jack.”

Maria smiles privately and takes a slow, careful bite of her manicotti. The change in tactics comes without warning. “How long did you say you would be in the States?”

“Six months.”

“And you’ve been here for, what, two? Three?”

Anna knows she’s being baited but she can’t see the hook. “Two.”

“What type of visa did you get?”

“Tourist.”

“A pity. International travel is so expensive.”

Anna does the thing she’s been doing for decades. She tilts her head up and to the side. She gives this woman the ghost of a smile, a condescending smirk that suggests she won’t acknowledge the insinuation or admit that yes, she’s running out of money and has few options left.

Maria is undaunted. She takes another bite. Dips her bread in the thick, nutty olive oil. Sips her wine. “And what will you do when your visa runs out? Will you go back to Germany? To your friends in Unterlengenhardt? Your pets?”

And there it is. The barb settles deep. It takes everything in her not to gasp in outrage. Maria clearly knows Anna doesn’t have a home to return to, that nothing remains but a mass grave behind the cottage she once called home. Maria’s involvement in those events hangs unspoken and heavy between them.

Rasputin’s daughter grins, victorious. “I suppose Prince Frederick would welcome you back. He’s always been so fond of you.” She chews a bite. Swallows. “Such a loyal man.”

Jack is oblivious, the fool. He ate a bowl of chicken Alfredo as big as his head, along with half a loaf of bread, and now he’s pushed back from the table to listen and pat his belly. To him this is simply a conversation between two women discussing old friends. To her it is blackmail.

Anna shrugs, noncommittal. “When you’ve lived as long as I have you take each day at a time. I’ve not settled on any firm plan.”

“Which means you don’t have one, correct?”

Jack and Patte look at each other, confused.

“What are they saying?” Jack asks.

“I don’t know,” Patte says.

It’s only then that Anna realizes that she and Maria have shifted into German. The transition was so smooth, so subtle that she didn’t even realize it. Had Maria turned the conversation to Russian, Anna would have noticed immediately. She would have refused to participate. Even though Anna speaks fluent English—she has lived in the United States before—German is her preferred language. Her security blanket.

“I thought as much.” Maria reaches across the table and pats Anna’s hand. It looks like a tender gesture, easily mistaken for something kinder than it actually is. “Don’t be ashamed. It’s hard. I know. Why do you think I’ve let Patte trail after me like a puppy for so long? We all have to make a living. There’s no shame in that.”

Anna withdraws her hand but doesn’t break eye contact.

“I want to make this perfectly clear. You will not use me as a meal ticket.” She selects this descriptor purposefully, saying it slowly, enjoying the look of recognition on Maria’s face. It’s the same phrase Maria used when she showed up unannounced in Unterlengenhardt and conspired to burn Anna’s world to the ground.

Maria laughs as though Anna has said something funny. She settles back into her chair, but now there’s an angry, dangerous glint in her eyes.

“I will not go to California with you. Or anywhere else for that matter. I will not sell my story.” Anna looks first to Patte and then to Jack as she repeats her earlier request in English. “I would like to go home.”

“Well, I would like dessert,” Maria says.

The table is already littered with plates and bread baskets and empty bottles of wine. Anna doesn’t think there’s room for another dish, but Maria waves the waiter over and orders panettone and coffee. Anna curses herself once again for not insisting that Jack drive. They are at the mercy of these interlopers. So she waits patiently as Maria finishes yet another course. This Rasputin is nothing more than an old woman acting like a petulant child, punishing Anna for refusing to play along.

“How did you find me?” Anna asks. This is the second time Maria Rasputin has hunted her down. It remains to be seen whether the results will be as catastrophic as the first time.

“It wasn’t hard.” She tips her head toward Jack. “This man you’ve taken up with is fond of the newspapers. You’ve been written up quite a bit since arriving in the United States.”

“I haven’t taken up with him.”

“Yet. I’d wager it’s only a matter of time. You do love your . . . benefactors.”

Jack and Patte have given up trying to follow their conversation and are chatting quietly about writing and research on the other side of the table. It’s almost nine o’clock before the waiter brings the check. Hours have been spent listening to first Patte, then Maria try to convince her to sign over the rights to her life story so they can make a film. They throw words around and name-drop. They suggest a variety of famous actresses who might play the role of Anastasia. She doesn’t bother to remind them that Ingrid Bergman has already done so and that the part won her an Academy Award in 1957. But neither of them is all that interested in Anna’s opinion. They are only concerned with what they see as a hefty payday.

Maria takes the check and Anna stands, relieved to be done with this dinner and on her way home again. But then she slides the bill across the table and sets it right in front of Anna. There is no charm or humor in her smile, only vindictiveness.

“It was wonderful to see you again . . . Anastasia,” she says. “Thank you for dinner.”

————

“What else would you expect from a Rasputin?” Gleb’s voice inches toward a scream as he paces through Jack’s living room. “Lying, thieving con artists, the lot of them!”

Jack flinches, defensive. “I didn’t know she stuck us with the bill. I wasn’t paying attention.”

“She didn’t stick you with the bill. You can afford it. She stuck Anna. And I’m sure that was her plan all along.”

“No,” Anna says. “If I’d agreed to her scheme, she would have paid. She was just trying to punish me.”

“You’ve been punished enough.”

Jack is embarrassed now. Flustered. “What was I supposed to do?”

“You could have started by not speaking with her at all.”

“It was just dinner.”

“It wasn’t just dinner; it was public association. A Rasputin gives our case a bad name. Every connection to that family is dangerous. Nothing good will come of it.” Gleb stops shifting from foot to foot and looks at Anna. “Do not mention to anyone, not a single person, that you spent the evening with that woman. Can you promise me that?”

Her silence says everything.

Gleb groans. “What?”

“She asked that biographer of hers to take a picture of us together before dinner.”

————

The photo is published several days later. It doesn’t make as many front pages as Maria Rasputin likely hoped for, but it does appear in the society columns of several newspapers, and it’s also picked up by the Associated Press. Before the week is out, half of America and much of the world knows that Maria Rasputin has declared Anna to be Grand Duchess Anastasia Romanov. Maria is interviewed at length, gushing about her long-lost friend, brought to tears even as she recalls their childhood memories. Anna burns the papers in disgust.

“We need those!” Jack yells in horror as the last of them goes up in flames.

Anna ignores him. She looks at Gleb. “I’m so sorry. I didn’t know she would do something like this.”

“You couldn’t have.”

That’s not entirely true, Anna thinks, but she doesn’t admit this to Gleb yet. Instead she asks, “How badly will this hurt the appeal?”

“No telling. The Rasputins are hated abroad. And for good reason. It depends who reads those articles. And how they’re perceived.”

“Surely the court won’t think that I’m behind this? That I’m fabricating evidence?”

“We’ll have to wait and see.”

Anna takes a deep breath before saying, “Maria mentioned one thing we should discuss.”

“What’s that?”

“What I’m going to do when my visa runs out.”

First sadness and then resignation settle into the fine lines around his eyes. “Don’t worry,” Gleb says. “I have a plan.”

Anna knows instantly what he has in mind. “No.” She cringes. His plans rarely turn out well.

“It’s the only way.”

“I won’t do it.” She lowers her voice to a whisper and casts a dismayed look at Jack Manahan. He sits across the room sorting through a pile of old newspapers.

Gleb matches her whisper for whisper. “You have to. I can’t do it. Look at me. The doctor says I have a year. Maybe. If I’m lucky. Jack can take good care of you.”

Anna drops her face into her hands. Here she is, cast once again onto a stranger. Beggared because her only friend has congestive heart failure. But it is her heart that aches at the moment. “If I marry him, I prove that Maria Rasputin was right all along.”

“What do you mean?”

“She said it was only a matter of time before I took up with him. She implied that I look to benefactors, that I use people.”

Gleb growls out a curse. “That woman is a scourge. We won’t let her near you again.”

“She can’t harm me any more than she already has.”

Gleb pulls away, confused, and Anna answers the unspoken question in his gaze. “Have I never told you about that? I suppose not. It happened right before I accepted your invitation to come here.”

“What happened?”

“The last time that woman showed up at my door unannounced, I ended up in the hospital for three days.”

2

Anastasia

Revolution

1917

Alexander Palace, Tsarskoe Selo, RussiaFebruary 28

The first shots ring out before dawn. I count fifteen—each of them splitting the air with a sound like cracking glaciers—before I go to the window and throw it open. Soldiers, drunk and mutinous, stumble through the park and onto the palace lawn. They shake their fists and fire wantonly at the sky as fear—hard, cold, and tangible—lodges in my throat. But still I watch, oblivious to the fact that any one of them could turn and aim a rifle at me. That any one of them could pull the trigger and pick me off as though I were a sparrow on a branch. I am frozen. Mesmerized by the chaos. Because even here, behind the palace walls and amid the muffling drifts of snow, I can hear rioting in the city and I know that fate has turned against us.

There is a whimper and rustling behind me, followed by a trembling voice. “Do not worry, Tsarevitch, the gunfire only sounds so loud and so close because of the frost.”

I shut the window and yank the curtains tight. I find our lady’s maid bent over my brother, her mouth close to his ear, her fingers pushing hair away from his eyes. “What are you doing?” I ask.

“He’s afraid,” Dova says, as though this excuses the lie.

The gunfire is loud and close. But the frost has nothing to do with it. Dova, however, fears upsetting my sickly brother—and therefore my mother—above all else.

“Are they going to kill us?” Alexey asks. His eyes are large with concern and he lies curled around his little brown spaniel. Joy pokes her curly head from beneath the blanket and sniffs at his chin. A smile twitches at the corner of his mouth as she licks him.

“No.” I perch on the edge of his cot and run my hand along Joy’s soft, floppy ears. “The Imperial Guard surrounds the palace. They will protect us.”

“Are you sure?”

“Of course. Would you like to see?”

Dova takes a step forward. “I don’t think—”

“He will be fine. But you should get some rest. You look exhausted.”

Dova doesn’t argue, but her mouth snaps open and then closed. She straightens her shoulders and, after a brief hesitation, offers a stiff curtsy and goes to bed.

I wait until she slips from the room before helping Alexey to his feet and taking him to the window. The arm Alexey hangs around my shoulders is thin as a willow switch, and I can feel his ribs press against my side. Born a hemophiliac, he’s been small and infirm his entire life, but since falling ill with the measles a week earlier, he has diminished to little more than shadow and bone. I want to take from my own soft form—all those places that my sisters poke and tease mercilessly—and pad the sharp points of his body. Ribs. Shoulder blades. Hips. I want to make him well again. To put color in his cheeks and laughter in his voice.

To his credit, my brother does not flinch when I show him the bright orange bursts of gunfire and the thin ribbon of flame at the horizon. We watch the chaos from a gap in the curtain, mindful not to push it open wide. I am careful with his life at least.

“What is that burning?” he asks.

“Tsarskoe Selo.”

“The entire city?”

“No. Just the parts closest to us.”

“Who lit the fires?”

“The people, most likely.”

“They must stop,” he says with an imperious sniff. “I do not approve.”

Alexey has known from birth that he will be tsar. Not just king or ruler, but emperor; sovereign of a dynasty that has ruled for more than three hundred years; leader of an empire that grows by fifty-five square miles every day; commander of a military that protects one-sixth of the earth’s surface. He is the recipient of a terrible, divine inheritance and I do not know how to explain that he cannot command this trouble away.

So I try to phrase it in a way he will understand. “I’m afraid they don’t care about your approval. Or Father’s. They do not want to be ruled any longer.”

“They don’t get to make that decision,” he says, unconcerned in the way only a child born of utter privilege can be. “They will be sorry for this when Father returns.”

If he returns. I think this but do not say it aloud. We have not heard from Father in days, nor do we know his current location. His last missive simply ordered us not to evacuate without him. And so we wait as the fires burn ever closer.

After locating the Imperial Guard in the courtyard, Alexey returns to his cot, wraps himself around Joy once more, and promptly falls asleep. At twelve, my brother hovers somewhere between foolish child and future monarch. He is spoiled and naïve, but I love him completely and irrationally.

When Alexey succumbed to measles, I offered the bedroom I share with Maria as an infirmary. It was only days later that Olga, and then Tatiana, joined him in the sick room. I convinced Mother and our beloved Dr. Botkin to let me play nurse and have tended them ever since. Now the three of them lie in their cots, picking at painful, itching rashes as they sleep, while I scrub my hands with harsh lye soap to keep the illness at bay.

I can see Olga’s pale face in the dark room, her eyes open now, a line of frustration carved between her brows. So she has only been pretending to sleep. Her clavicles protrude with alarming definition as she pushes onto her elbows. “You are a terribly good liar, Schwibsik.”

I grace my sister with a smile befitting my nickname. Little Imp. “I do not know what you’re talking about.”

Olga rolls her eyes and places her long, elegant fingers on the blanket beside her. Piano-playing fingers, Mother calls them. “You told Alexey we are safe.”

“No. I told him that the Guard would protect us.”

“Semantics.”

“You can say it, but can you spell it?” I ask. “Or is Master Gilliard right about your hopeless academic prospects?”

Olga smiles. “Gilliard adores me. You’re the one who should be worried. He’ll force you to study Latin for another year if your attitude in the schoolroom doesn’t improve.”

“That man is a pestilence, an oozing sore upon my brain.” Pierre Gilliard and I have had an ongoing feud since he began tutoring us several years ago, though we are currently at a stalemate concerning my lessons. But he is the least of my concerns tonight. I set a hand on Olga’s forehead only to find that it is still hot. “Besides,” I say, “we are safe. For now.”

“Liar,” she says, again, but with a smile this time. “We are under siege.”

“What would you know of it? Your eyes are swollen shut.”

“Only the left one. Besides, my ears are in perfect working order.”

“Your ears,” I counter, “are tuned only to hear flattery.”

She laughs at this, and I feel as though I have won a small victory. Laughter in the face of fear is no small accomplishment. But Olga’s rally is short-lived. Her smile dissolves and she flops back onto her pillow, depleted. She is asleep in seconds and I mop her damp forehead with a cloth, feeling hollow and exhausted myself. I make one final pass through the room, tucking the covers around Alexey’s shoulders and reapplying cold compresses to the flushed foreheads of my sisters.

My own dog, Jimmy, is curled beside the fire with Tatiana’s French bulldog, Ortimo. Jimmy watches me cross the room, his ears up and alert, while Ortimo snores like an ugly, drunken sailor, splayed on his back, legs spread and tongue lolling to the side.

“Come,” I say, and Jimmy immediately lurches to his feet. I am always amazed at how he can move that huge body so quickly. The small black puppy Father gave me years ago has turned into a great lumbering beast half my height and weight. We knew Siberian huskies grew large; we simply didn’t expect him to be this large. “Let us go learn the truth of this siege.”

————

Four short taps on Mother’s bedroom door let her know which of her children waits outside. I know she will be awake just as I know my sister Maria will be sprawled in her bed, snoring and oblivious, her soft curly hair spread out on the pillow, and her dark lashes fanned across her high cheekbones. Since Olga and Tatiana fell ill, and with Father gone, Maria and I relish our more frequent turns sleeping in Mother’s great canopied bed, and we fight over it in the small, petty ways that only sisters can.

“Come in, Schwibsik,” Mother says.

So she is feeling sentimental. A good sign. I take a deep breath and push the door open, with Jimmy trotting at my heels. Mother stands before the window watching revolution spill onto the palace grounds. She is of practical British stock, after all, and it is her people who pioneered a form of battle so orderly that men stand in rows and shoot at one another by turns. Yet upon closer inspection I see that it is disdain, not courage, that is etched into the tight corners of her mouth.

“Mother?”

“You should be asleep,” she says, beckoning me to her side.

“Everyone keeps saying that.”

“Everyone is right.”

“I can’t sleep through this.” Out across the grounds, where the manicured lawn rolls down toward the edge of the park, the muzzle flashes are dimmer now against the growing light. “I don’t understand what is happening.”

“Revolution, it would seem.” She snaps the curtain closed and moves toward a long, padded bench at the foot of her bed. Mother pats the seat and I curl up next to her, my eyes suddenly heavy and dry. “They’ve been threatening it for years,” she says.

I think of my father and how, when we were little and naughty, he would threaten and threaten until he finally snapped and bent one of us over his knee. Perhaps, like Father, the people have grown tired of threatening.

“What do we do now?” I ask, my voice tremulous with exhaustion and growing fear. Jimmy, ever sensitive to my moods, presses his cold, wet nose against the back of my hand.

Mother clutches the amulet at her throat. It was given to her by Grigory Rasputin shortly before his murder last year and is identical to the ones she requires each of us to wear at all times. “We pray,” she says.

————

Most of the servants flee that first night. They slip quietly from the palace in groups of three and four. Some go out to smoke their hand-rolled cigarettes with trembling fingers and don’t return, not for their friends and not for their coats. Others finish their work and walk boldly through the servants’ entrance and into the night, toward Tsarskoe Selo and the burning horizon. Some take silverware and candlesticks, knowing they will never receive their final wages. A few cry, but most never look back as they tromp through the snow with their heads down and their collars turned up against the wind.

Cook tells me this in the morning when I wander into the kitchen, bleary-eyed, in search of the chambermaid and our missing breakfast.

“I watched them go. Every damn one,” he says. “Sat right here and they didn’t so much as lift an arm in farewell. That maid of yours was the last to sneak away. She left the door open in her haste.”

He stands in front of a great, sweltering woodstove, boiling eggs and coffee. I drift closer, drawn by the warmth and smell of breakfast, until I am dwarfed by his bulk. Cook is a giant of a man. Arms like posts and legs like pillars. Voice like the boom of a cannon. His jaw is as square and strong as a granite cornerstone. It is his back that commands attention, however. It is twice the width of a normal man and corded with muscle. I’ve heard the maids whisper that normal men can’t grow a back like that unless they’re under duress. I’ve heard them say he must have been sentenced to man the oars in a prison ship. Or hew stone in a gulag. All ridiculous, unfounded rumors that Cook never bothers to dispel. He likes the mystery, I think. Likes it when the servants scurry from his path. But to me he is simply Cook. Baker of bread. Maker of coffee. Teacher of profanity. Not that I would ever admit this last part to my parents. I like the man too much to see him dismissed.

“I can’t let you carry that yourself.” Cook scowls at a silver platter now holding a steaming carafe and a plate of warm French rolls fresh from the oven. “Where is Dova?”

“Sleeping.”

He grunts, as though this is a moral failure.

“I can take it upstairs. I’m strong enough.”

“That’s not the point. Your mother would have my head.” He looks around the kitchen, as though to grab the first person who passes, but we are quite alone. Everyone else has fled.

There are few men who can make cursing sound like poetry, but Cook is one of them. I don’t blush and he doesn’t apologize when the diatribe is complete. Instead he carefully lifts the tray and stomps from the kitchen with me in tow.

Dova meets us upstairs on the landing looking somewhat abashed but eager to see breakfast. She murmurs thanks, and Cook gently relinquishes the tray into her waiting hands before he retreats to safer, more familiar territory downstairs. As Dova leads me back to my chambers I tell her what I’ve learned about our missing chambermaid and the other servants.

“Cowards,” she hisses, and pours me a cup of coffee. It is warm between my hands, comforting, and we settle beside the fire, listening to the popping, hissing sounds as we sip the dark, fragrant brew. Coffee is an art form to Cook and we are his devoted patrons.

It doesn’t take long for Mother to join us, still wearing her dressing gown. Maria, I assume, is still asleep. Undeterred by the missing chambermaid, she waves Dova aside and goes straight to the coffee and fills a cup, then drowns it in cream and sugar. I have never seen Mother pour her own coffee before, and I marvel that she is familiar with such a small domestic task. It is so unlike an empress. She drinks the entire thing with her eyes closed before imparting her news.

“The telephone lines have been cut,” she says. “The electricity has been turned off. So has the water. You know about the servants, of course. Most of them are gone. They left because they are afraid. I don’t blame them, I suppose, but I would be lying if I said I don’t hate them a little for it.” Her voice is steady but her hand trembles as she lifts her cup to her lips.

“What about the guards?” I ask.

“They’re still here. For now.”

“And Father?”

“God only knows.”

By midafternoon, the palace is flooded with reports of brawls and bombings, of shootings in Tsarskoe Selo and men lying dead in the streets. Things are, according to Cook, apparently no better in Petrograd, thirty kilometers away. Here at the palace all that remains between us and mutiny is the Imperial Guard and the protective circle they maintain. It is a feeble shield—no thicker than an eggshell—and even they keep a wary eye turned toward the billowing line of smoke at the horizon.

————

It is nearing sunset when Viktor Zborovsky, captain of the Imperial Guard, kneels before Mother and kisses her hand. He is a great, tall man with kind brown eyes and a beard so white that I believed him to be Ded Moroz—or Grandfather Frost—for an entire decade.

“I am so sorry, Tsarina. Alexander Kerensky has ordered the Imperial Guard to stand down. If we refuse, we will all be shot for treason.”

Kerensky. This name is familiar, but I have little reason to place it. Alexander Kerensky is in the government, and Father runs the government, and that’s all I have ever cared to learn about political structure. Now every name and rank and title suddenly matters, and I find myself struggling to keep them all straight beyond the general categories of “for us” and “against us.” Kerensky, I suspect, falls in the latter.

Mother gives Viktor a gracious nod. “Do not fight. There is no point.”

“You are kinder to us than we deserve.” He rises from her feet and sits across from her at the fireplace. “The entire combined regiment will be sent back to Petrograd tonight. We’re being replaced with three hundred troops of the First Rifles, all of them under Kerensky’s command.”

“And what of us? What do they intend?”

“I am told that once the tsar arrives you will all be sent to Murmansk where a British cruiser will carry you to England.”

“I’d hoped for Crimea,” Mother whispers.

“I think that is more than anyone can hope for, under the circumstances.” Viktor takes a deep breath and releases it slowly. He fiddles with the brass buttons on his jacket for a moment, then says, “It pains me to leave you unprotected. I don’t like the whispers coming from Petrograd.”

“Nicholas will be here soon. Everything will be fine once we’re all together again. Please. Don’t create trouble for yourself or your men. I don’t want anyone’s son sent before a firing squad on our account.”

“The Guard asked me to pass along their sentiments. They remain loyal in their hearts. Please do not judge them for leaving.”

“I judge no one other than those cadets from Stavka you brought in to play with Alexey last month. One of them infected him with the measles, and now Olga and Tatiana are ill as well.” The words are harsh but she says them with a smile.

Viktor Zborovsky looks to Mother for absolution and she grants it in her own way, rising from her chair beside the fire and crossing to a small sideboard where she chooses a hand-painted icon of Saint Anna of Kashin—holy protector of women—and places it in his hands. “Take this as a sign of my gratitude,” she says, and then whispers so low that I almost don’t hear, “You know what to do with it.”

Viktor wraps the icon in his kerchief and tucks it inside his coat. “They let me in through the main entrance. Everything else, apart from a side door in the kitchen, has been locked and sealed. Guards are stationed at all the doors, and the first-floor windows are nailed shut. Anyone in your court who wishes to leave will have to go through the main entrance and they will be required to give their names and their relationship to your household. All the information given will be recorded. I’m sorry for that. There is nothing I can do.”

“You have done enough. Take your men to safety.”

Mother and I stand at the window once again, more aware than ever of how completely we have been separated from everything on the other side of the wall. We watch as Viktor gathers the men of the Imperial Guard and marches them from the palace in orderly ranks. We watch as our beloved soldiers and friends are replaced by three hundred strangers who are loyal to a regime that hates us.

“What did you put in that icon, Mother?”

She smiles. “Oh, you are a clever girl.”

“It wasn’t just a gift, was it?”

“No. It was a message.”

“What sort?”

“The sort I hope we do not need.”

A disconcerting silence falls between us again as the soldiers of the First Rifles are being ordered about in the courtyard.

After a moment I say, “At least one good thing came of this.”

“Is that so?”

“We are going to England.”

“Are we?”

“You don’t believe him?”

Mother motions to the cobblestone courtyard below where an artillery gun is being wheeled across the stones and aimed toward the house. And there behind it stand one hundred men and their wall of bayonets.

“I suspect that part was a lie,” she says.

3

Anna

Departure

1968

Neuenbürg, GermanyAugust

Anna wakes in the hospital. She knows immediately that she has been drugged because she has to pull herself up and out of the fog, to work at keeping her eyes open and her mind clear. This is an old, unpleasant, and unwelcome sensation. The difference this time is that she comes to, not in an asylum but in a hospital. There is no screaming. No crying. It smells of antiseptic instead of urine. And she is in a room by herself instead of in an open ward. It is as though she’s surfacing headfirst from the bottom of a deep, dark pool. Anna can think before she can move her limbs; the result is a brief, suffocating panic in which she fears she is paralyzed. But within moments the rest of her body begins to cooperate and she is once again able to wiggle fingers and toes.

Anna feels the IV in the back of her left hand. The site is stiff and sore; she peels off the tape and pulls the needle from her skin. There is a brief, cool, bizarre feeling as it slips out of her vein, like someone has drawn a sliver of ice from beneath her skin.

Two bags hang from the stand beside her bed, one large and filled with glucose, and the other small and empty. Anna guesses the latter to be a sedative.

Her clothes are folded in neat little rectangles on the chair beside the bed, her shoes perched on top. The hospital gown she wears is clean and white and buttons up the back. They’ve removed her undergarments as well, which means they’ve seen the worst of her scars. This violation of her privacy never gets easier. It is bad enough that the eyes of strangers are always drawn to the thin, silvery lines at her temple and collarbones. But those are small and curious compared to the jagged, puckered scars on her torso and thighs. Her visible scars suggest there might be an interesting story involved. But the ones hidden beneath her clothes tell the grisly truth of what happened to her all those years ago. It is why she does not willingly allow others to see her naked. There is simply no way to explain. And she cannot tolerate the pity that comes with their discovery.

Anna swings her feet lightly over the side of the bed and places them on the cold floor. She tests her balance. And when she’s certain that the drugs have faded from her system, she stands. She is clothed in moments, each article jerked onto her thin frame with little attention paid to tags and buttons or concern for neatness. She cares only about having her armor in place once again. So when a nurse enters several minutes later, she finds Anna standing at the window, arms crossed, as though prepared for battle.

“You’re awake!” The nurse is young and plain but absurdly cheerful.

“Where am I?” Anna demands.

“The district hospital at Neuenbürg.”

“Why?”

“They found you unconscious and brought you here.”

“They?”

“The paramedics. You were on the floor, unresponsive.”

“No,” Anna says, “they drugged me.”

The nurse hesitates. Then smiles. It’s meant to be a reassuring gesture. “Only because you resisted.”

“Who wouldn’t resist being drugged?”

“You resisted coming here.” Now a tight-lipped smirk.

“How could I do such a thing if I was unconscious?”

Anna knows what she looks like, a somewhat senile and helpless old woman in her early seventies. But this young nurse has just realized the incongruence between her appearance and her intellect and is adjusting accordingly. This time the smile she offers Anna is one of concession.

“Would you like me to fetch the doctor? I’m sure you have questions.”

“Yes.”