Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

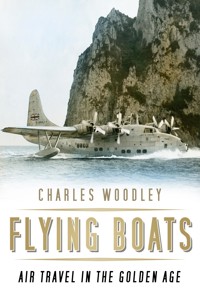

Flying Boats: Air Travel in the Golden Age sets out to do justice to a time of glamorous, unhurried air travel, unrecognisable to most of today's air travellers, but sorely missed by some. During the 1930s, long-distance air travel was the preserve of the flying boat, which transported well-heeled passengers in ocean-liner style and comfort across the oceans. But then the Second World War came, and things changed. Suddenly, landplanes were more efficient, and in abundance: long concrete runways had been constructed during the war that could be used by a new generation of large transport aircraft; and endless developments in aircraft meant they could fly faster and for further distances. Commercial flying boat services resumed, but their days would be numbered.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 242

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Front Cover: Aquila Airways Short Solent G-ANAJ City of Funchal taxies past steep cliffs during the inaugural flight to Capri in 1954. (via Dave Thaxter)

Back Cover:Top and Middle: Qantas posters promoting the airline’s UK–Australia Empire flying-boat services. (Qantas Heritage Collection)

Bottom: An Aquila Airways luggage label. (Dave Thaxter)

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Charles Woodley, 2018

The right of Charles Woodley to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 7014 3

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

CONTENTS

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Imperial Airways and the Empire Air Mail Scheme

2 Pan American Across the Pacific

3 Transatlantic Beginnings

4 Wartime Interlude

5 Return to Peacetime Operations

6 The Princess Flying Boat

7 Aquila Airways

8 Australia and the South Pacific

9 South American Operations

10 Norwegian Coastal Services

11 Preserved Flying Boats

Appendix 1 Foynes Flying Boat Movements During September 1943

Appendix 2 Fleet Lists of Major Flying Boat Operators

Sources of Reference

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Throughout this book I have used the place names in use during the period covered. Many of them have changed in the intervening years and their modern-day versions are as follows:

Belgian Congo

now Democratic Republic of Congo

Calcutta

now Kolkata

Canton Island

now Kanton, part of Kiribati

French Equatorial Africa

now several independent countries under the name of Union of Central African Republics

Jiwani

was in India, now in Pakistan

Karachi

was in India, now in Pakistan

Malakal

was in Sudan, now in South Sudan

Malaya

now Malaysia

Northern Rhodesia

now Zambia

Nyasaland

now Malawi

Rangoon

now Yangon, in Burma/Myanmar

Salisbury

was in Rhodesia, now Harare in Zimbabwe

Sumatra

was in Dutch East Indies, now in East Java province of Indonesia

Surabaya

was in Dutch East Indies, now in East Java province of Indonesia

Tanganyika

now Tanzania

Trucial Oman

was part of the British Empire, now part of the United Arab Emirates

Wadi Halfa

was in Sudan, now in South Sudan

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people and organisations have kindly assisted me in the preparation of this book by sending me images, memories, information and good wishes for its success. They are listed below with my thanks, but if I have inadvertently omitted anyone I apologise and thank them once again.

Chris Smith at the Solent Sky Museum

Ron Cuskelly at the Queensland Air Museum

David Cheek at GKN Aerospace

Aimee Alexander at the Poole Flying Boat Celebration

Barry O’Neill at the Foynes Flying Boat and Maritime Museum

Dave Thaxter at the British Caledonian website

Judy Noller at Ansett Public Relations

David Crotty, Curator, Qantas Heritage Collection

Doug Miller, webmaster at the Pan Am Historical Foundation

Kim Baker

Peter Maxfield

Felicity Laws

Elizabeth Malson

Beryl Cawood

Hilary Adams

Jeremy Cutler

Les Ellyatt

Peter Savage

Janet Beazley

Chris Mooney

Sue Marks

Paul Sheehan

Anthony Leyfeldt

Frank Stamford for his Lord Howe Island flying boats images

Jenny Scott at the State Library of South Australia

My friend Raul in Buenos Aires for finding me rare South American flying boat images

Amy Rigg at The History Press for her continuing faith in my abilities and her encouragement

And, of course, my wife Hazel.

INTRODUCTION

At the beginning of the 1930s Britain ruled over an empire that spanned the globe, but travel between the mother country and its far-flung overseas possessions was a laborious and time-consuming process. The journey to Karachi (then in India) took some seven days and involved transfers between trains, ships and aircraft along the way. The need for speedier transportation of the all-important mail and the few passengers that accompanied it led to the setting up of the Empire Air Mail Scheme, whereby all mail to and from the Empire would be transported by air throughout at a government-subsidised standard rate. In order to accommodate the anticipated volume, larger and more modern airliners would be needed, and in response to a request for proposals the Empire-class flying boat designs emerged. Built by established flying boat manufacturer Short Bros, these would be capable of carrying the mail as well as a small number of cosseted passengers all the way to Africa, the Middle East and India in new standards of comfort. The lack of land airports and night-flying facilities along the routes would be bypassed by using marine facilities with long water take-off areas, and all flying would take place during the daylight hours, with the passengers spending the nights in luxury hotels or company-owned houseboats, all included in the fare. The introduction of the Empire-class flying boats by Britain’s state airline Imperial Airways certainly ushered in new standards of passenger comfort and attentive service, but the aircraft were still far from fast, the journey could be uncomfortably bumpy at times, and the fares were beyond the reach of the average working man.

In the meantime, on the other side of the Atlantic, the USA’s overseas ‘flag carrier’ airline Pan American Airways was operating smaller Sikorsky flying boats to the Caribbean islands, the West Indies, and down the coastline of South America. The airline’s founder, Juan Trippe, had more ambitious plans though, for flying boat services across the Pacific to the Far East via Hawaii. Before such plans could become a reality, however, staging posts would have to be constructed on a string of small islands such as Wake and Midway along the route. The airline set to and installed refuelling facilities for its aircraft and luxury hotel accommodation for its passengers at these stopover points, and in due course the services were inaugurated, using a new generation of giant Martin and Boeing Clipper flying boats.

Both Imperial Airways and Pan American then turned their attention to the much trickier proposition of North Atlantic operations between Europe and the USA. The route involved battling against inclement weather conditions for much of the journey, and experiments were carried out to determine the practicality of in-flight refuelling to give the necessary range. Some experimental services were operated by both carriers in 1940, but further progress with operations across the Atlantic and the Pacific were then disrupted by the Second World War, which saw the airlines operating according to wartime priorities on behalf of their governments.

When commercial airline services resumed after the war, much had changed. During the hostilities new land airfields with long concrete runways had been constructed for use by large four-engined bombers. Both the airfields and the aircraft could be adapted to fulfil short-term airline needs, and the commercial flying boats soon became redundant. Britain’s new national airline, BOAC (which had replaced Imperial Airways in 1940), kept faith with its flying boats for a few more years, operating them on popular and well-patronised services from Southampton to South Africa until late-1950, when they were replaced by landplanes. Many of the retired BOAC flying boats then found a new home with Aquila Airways, flying holiday services to the island of Madeira, which at that time had no land airport. They were to serve this route, and others to Las Palmas and the Isle of Capri, well for several years. Other flying boats were operated in the South Pacific area, carrying passengers to romantic destinations such as Tahiti and Lord Howe Island, and they also gave useful service in South America and along Norway’s northern coastline, but they eventually reached the end of their operating lives. No replacements were built, and the era of the passenger flying boat passed into history. This book sets out to do justice to an age of glamorous, unhurried air travel, unrecognisable to most of today’s air travellers, but sorely missed by some.

1

IMPERIAL AIRWAYS AND THE EMPIRE AIR MAIL SCHEME

On 1 April 1924 the British airline Imperial Airways came into being as the product of the merger of Handley Page Air Transport, The Instone Airline, Daimler Airways, and British Marine Air Navigation. These independent airlines had been unable to compete effectively against the state-backed carriers of countries such as Germany and the Netherlands, and their incorporation into a British government-subsidised ‘flag carrier’ was seen as the key to operating efficiencies and future expansion to serve the global outposts of the British Empire. In the late 1920s the fastest journey to Karachi (then in British India) took seven days and entailed a landplane flight from Croydon airport to Basle followed by rail travel to Genoa, where a flying boat was boarded for the air journey to Alexandria in Egypt. From there another train conveyed passengers to Cairo, where they embarked on a DH.66 landplane for the final leg to Karachi. Even in 1934 passengers wishing to travel speedily between London and Athens had to first fly from Croydon to Paris by landplane before boarding a train for the 950-mile leg to Brindisi and then switching to a Short S.17 Kent flying boat to get to Athens. Part of the reason for these convoluted itineraries was Italy’s reluctance to grant overflying rights to Imperial Airways, and it took until 1936 for these to be negotiated. The way was then clear to make plans for travel entirely by air to all parts of the Empire. A major boost to these ambitions came with the government announcement in December 1934 of the Empire Air Mail Scheme (later renamed the Empire Air Mail Programme), intended to speed up communications between the territories of the Empire and the mother country. From 1937 Imperial Airways would receive a subsidy to carry nearly all of the mail to South Africa, India, Australia and New Zealand and other Empire territories at the same rates as surface post. It was calculated that in order to carry the anticipated quantities of mail as well as some passengers the Imperial fleet would need to be expanded to be capable of operating four or five flights each week to India, three per week to Singapore and East Africa, and two each week to South Africa and Australia. New and larger aircraft would need to be designed, and the Air Ministry expressed its insistence on these being flying boats, giving as its reasons:

Imperial Airways Short S.23 G-ADUZ Cygnus unloading at her moorings. (via author)

That neither the government nor Imperial Airways could afford the investment needed to enlarge existing land aerodromes, many of which became unusable during the monsoon season in certain countries.

That flying-boats provided a greater sense of security during flights over long stretches of water and would also be able to circumvent problems over the granting of landing rights in certain countries by flying more direct routeings, also reducing fuel costs.

That flying-boats would be able to provide greater comfort for passengers, even though the mail would always be given priority for space.

Thus, despite certain economic penalties they would incur, the flying boat was seen as the best option for the new services. It was agreed that the government would provide an annual subsidy of £750,000, and the Post Office an additional £900,000, for the carriage of the mail, plus an extra £75,000 to cover the cost of extra flights over the Christmas period. Imperial Airways also managed to persuade the Admiralty to provide all the launches, refuelling tenders, and mooring facilities along the routes free of charge.

In order to compete with the speedy landplanes of its competitors, such as the Douglas DC-2s of the Dutch airline KLM, Imperial needed spacious flying boats that could offer its passengers unrivalled comfort and facilities on a par with the ocean liners of the day. In order to get such aircraft into service with the minimum of delay, Imperial Airways invited Short Bros of Rochester in Kent to submit a design for an improved version of its existing Kent flying boat, which could also meet an RAF requirement for a long-range maritime patrol aircraft. The result was the Short S.23, an all-metal high-wing monoplane of clean lines with a deep hull, single tailfin and rudder, and fixed wing-tip floats. The aircraft’s interior was divided into two decks, and power was to be provided by four 740bhp Bristol Pegasus Xc piston engines. Imperial was sufficiently impressed by the design to order twenty-eight examples at a cost of around £45,000 each before a prototype had even flown. The Air Ministry also ordered a prototype of the military S.25 version (later to become famous in RAF service as the Short Sunderland). Imperial had originally wanted to give its machines the class name the Imperial Flying boat, but soon changed this to the Empire Flying boat. Construction of the order commenced at Rochester in 1935, and the first example, registered as G-ADHL and carrying the name Canopus (all of the Imperial fleet were to be allocated names beginning with C and to become known as the C Class), first flew from the River Medway on 3 July 1936. On the following day an official ‘maiden flight’ was staged in front of the entire workforce. No aircraft of such size and complexity had been built before by Britain, and the press were allowed to inspect the almost fully fitted-out Canopus shortly afterwards. One reporter described the aircraft in rather Jules Verne or H.G. Wells prose as follows:

Mailbags being unloaded from Imperial Airways Short S.23 G-ADHM Caledonia into a launch. (via author)

A diagram of the Imperial Airways flying-boat routes to Africa, India and through to Australia c. 1938. (via author)

A 1939 Imperial Airways advertisement showing its Empire flying-boat service frequencies before the Second World War intervened. (via author)

An Imperial Airways magazine advertisement for their newly introduced Empire flying-boats on the route to India. (via author)

No aeroplane yet built has given that same sense of freedom to move and breathe. Every saloon has a breadth and height in excess of the best that rail or road transport can offer ... The forward part of the deck is fully occupied with the gear of control navigation and communication. The instruments and the apparatus, from the loop aerial of the directional wireless to the artificial horizon and the switch for the landing lights, the levers, dials and levels, makes the pilots’ compartment a mass of complications, and foreshadows the day when the big aeroplanes, such as certainly will be built for ocean crossings, will need an engine room separate from the bridge.

The promenade deck cabin on an Imperial Airways Empire flying-boat. (via author)

Forward saloon of an Empire flying-boat. (via author)

A cutaway view of the new Empire flying-boats used on the Imperial Airways and Qantas services to Australia. (Qantas Heritage Collection)

The Imperial Airways order was later increased to thirty-two examples, plus six more to be delivered to Australia for use by Qantas Empire Airways on services between Singapore and Australia, and two more for completion to long-range S.30 specification for use on trials for possible transatlantic services. After crew training and acceptance trials had been completed, Canopus was handed over to Imperial Airways on 20 October 1936. The rest of the fleet followed at intervals of one or two per month. On 22 October Canopus set off for Genoa for service on trans-Mediterranean routes. The first scheduled service to be operated by an Empire flying-boat left Alexandria for Brindisi via Mirabella and Athens on 30 October, and on 4 January 1937 the route was extended onwards from Brindisi to Marseilles.

The flying boats were more than just aircraft that could land on water, they were boats that flew, and many nautical terms were used to describe their structure and operation. Passengers boarded via a forward door on the port side of the lower deck and entered the lobby area, which was curtained off from the passenger cabins. Forward of this was a compartment containing seven seats and lightweight stowable meal tables. This cabin featured a large rectangular window and was at first used as a smoking cabin. The décor consisted of bottle-green walls and white ceilings, and the seats were upholstered in dark green leather. Aft of the entrance door was a central corridor offset slightly to port, with the galley and stewards’ pantry to one side and two toilets on the other. Continuing aft, the corridor led to the midships, or ‘spar’ cabin, which seated three passengers in the daytime and could be converted to bunk accommodation for overnight flights. Further aft along the corridor small steps led into the promenade cabin, which was fitted with seats for eight passengers on the starboard side. On the opposite side there was ample space for passengers to stand and lean on an elbow rail whilst observing the scenery and wildlife passing below through the large window area. Once again, if night flying proved necessary, the seats in this area could be converted into four bunks. Moving rearward again, a small step upwards brought one to the rear door on the port side, and up another step was the rear cabin with accommodation for six seated passengers or four in bunks. In practice, the sleeping berths were almost never used on scheduled services as full night-flying facilities were not to be installed along the routes for some years to come. The rear cabins were furnished with grey carpeting and dove-grey ceilings, with the walls and seat coverings in bottle green. Also on the lower deck were compartments for luggage and freight, and in the nose of the aircraft was a mooring compartment with such nautical accoutrements as an anchor, boat hooks and a retractable mooring bollard.

The Imperial Airways Short S.23 flying-boat G-ADHM Caledonia at her moorings with a launch alongside the forward door. (via author)

Imperial Airways Empire flying-boat G-AETX Ceres on the water near Mombasa. (via author)

Underneath the decking were bilge pumps for disposing of any water that seeped into the hull. The upper deck was accessed by a ladder from the stewards’ pantry, and was normally out of bounds to passengers. On the flight deck, or ‘bridge’, sat the captain and first officer. Behind them, and facing aft, was the wireless operator. He was also responsible for mooring the aircraft. To perform this task he had to descend to the mooring compartment via a small hatch in the floor between the pilots’ seats. Aft of the wireless operator’s station was the mail storage area. Towards the rear of the upper deck was the desk of the flight clerk, whose many duties included the preparation of the aircraft’s load sheets and trim sheets, the compilation of passenger lists, the handling of freight consignments, the customs and immigration procedures, and the safekeeping of the inoculation certificates of the passengers and crew. In the event of overnight flights he was also expected to descend to the lower deck and help the stewards to make up the bunks using bedding stored in the aft portion of the wing box, above the promenade cabin. From mid 1937 his rather inconveniently sited workstation was relocated downstairs into what had previously been the forward smoking compartment. He was also given the grander job title of purser. The Empire flying boats did not carry an engineering officer or navigating officer, their duties being carried out by the first officer. On top of the flight deck was a mast from which the appropriate ensign could be flown during stopovers. The pilots had to put up with some discomfort on these aircraft. The controls for the Sperry autopilot were located on the captain’s side and tended to leak oil onto his left trouser leg, and when it rained the leaky flight deck roof dripped water onto both pilots. The passengers were always looked after by male stewards, mostly recruited from the ocean liners of the Cunard steamship company. Imperial Airways was against the employment of stewardesses on any of its aircraft. As the company put it:

This curious hybrid nursemaid-cum-waitress was not the best way of putting the passengers at their ease ... Our aerial stewards are men of a new calling. They have to be, since much is expected of them. In less than an hour a couple of flying stewards can serve six courses, with wines, to between thirty and forty people.

The first C-class scheduled service was operated from Alexandria to Brindisi by Canopus on 30 October 1936, fewer than sixteen weeks after she had been launched. In December of that year sister ship Caledonia was flown out to Alexandria with 5 tons of the Christmas mail on board. She continued onwards to India on route-proving duties. On her way back to Britain she covered the leg from Alexandria to Marseilles in just over eleven hours, and flew onwards to Hythe, near Southampton, in four hours. In January 1937 Castor and Centaurus commenced a regular series of flights from Hythe to Marseilles and Alexandria via Lake Bracciano (for Rome), Brindisi and Athens.

The Imperial Airways Short S.23 G-ADUW Castor at Gladstone, Australia. (via author)

Hythe had been selected by Imperial Airways for use as a temporary UK flying boat terminal in 1934, after serious consideration had also been given to the use of Langstone Harbour at Portsmouth, while the site for a permanent base was still to be decided. A maintenance base was also set up at Hythe, in sheds rented from Vickers Supermarine Aviation. To get to the terminal from London, passengers travelled on the 0830hrs train from Waterloo Station to Southampton in a dedicated Pullman railway carriage proudly bearing the title ‘Imperial Airways Empire Service’. Also attached to the train was a special guard’s van in which the aircraft’s flight clerk processed the luggage details and compiled the load sheet en route to Southampton. Imperial was to experience difficulties in getting the passengers there in time for the mid-morning flight using this train, and the decision was taken to transport them down the previous evening and put them up in a hotel overnight. In the morning the passengers would clear customs at Berth 50 at Southampton and be transferred to the aircraft moored off Hythe in one of the many launches that had been built for Imperial by the British Power Boat Company. Boarding the launch and then transferring to the flying boat was a tricky procedure in any kind of rough weather, particularly for the less agile passengers, and operations were later to be moved to the more sheltered No. 9 Berth while pontoons were constructed at 101 Berth. Once this work was done the flying boats could be winched tail-first into moorings at the quayside, eliminating the need for the launch transfer. In late 1938 the pontoons were to be moved to Berth 108, where a two-storey wooden terminal building named ‘Imperial House’ was erected. Things did not always run smoothly on these services. On 6 February 1937 Captain H.W.C. ‘Jimmy’ Algar was in command of Castor for a service from Hythe to Alexandria. On board were eight passengers, a ton of mail and five large cases containing bullion. One more passenger was booked to join the flight at Marseilles, and another at Brindisi. The take-off from Hythe was uneventful, but ten minutes later the aircraft returned, suffering from oiled up spark plugs. The plug change took longer than expected, and by the time the aircraft was serviceable again it had become apparent that Brindisi could not be reached that night. The passengers were taken off to spend the night at the Lawn Hotel in Hythe and police were called in to guard the bullion. Rough weather made operations impossible the next day, and so it was not until 0720hrs on 8 February that the flight eventually departed. On 24 March Imperial Airways lost C-class flying boat Capricornus in a fatal accident. The aircraft was en route from Hythe to Marseilles when it struck a hillside 12 miles south-west of Macon in France. It was carrying just a single passenger, plus a consignment of bullion and the first mail scheduled to be transported all the way to Australia by air. The first officer was thrown out of the aircraft on impact and was the only survivor.

An Imperial Airways magazine advertisement for their new Empire-class flying-boats, featuring the promenade deck cabin. (via author)

From 15 May 1937 the C-class flying boats operated through to Africa, although at first only as far as Kisumu, a freshwater port on Lake Victoria and Kenya’s third-largest city. About fifteen minutes before arriving there the aircraft crossed the equator, and to mark the crossing of this invisible feature the Imperial pilots used to waggle the wings or dip the aircraft’s nose, and it was customary for each passenger to be presented with a certificate signed by the captain. As the flying boat fleet was expanded, the route was extended through to Durban, with Centurion departing Hythe on 29 June 1937 for the Sudan, Northern Rhodesia, Nyasaland and South Africa with 3,500lb of unsurcharged mail at the surface post rate of 1½d for a half-ounce letter and 1d for a postcard. Imperial was not allowed to operate all the way through to the Cape as the South African authorities had specified that only South African Airways could fly into Cape Town. Until 1937 the usual mode of travel to South Africa had been aboard the Union Castle Line’s weekly mail steamer from Southampton, which took two weeks to reach the Cape. By September of that year Imperial Airways was flying twice-weekly to South Africa, and produced a thirty-page booklet for passengers titled ‘Through Africa by the Empire Flying boat’. This traced the entire route from Hythe and described the many points of interest along the way. Over Africa the pilots often descended to low altitudes to offer passengers excellent views of herds of elephants, plus rhinos and giraffes on the plains below. A favourite spot for viewing hippos was just below Murchison Falls at the northern end of Lake Albert in Uganda. The one-way fare to South Africa in 1937 was £125, which included all meals, overnight accommodation and tips, and was based on the criteria that the total weight of each passenger and luggage would not exceed 221lb. For this price the flying boat passengers enjoyed far more space and more attentive cabin service than today’s economy-class passengers are accustomed to, although the low cruising altitude of the unpressurised aircraft did mean that turbulence was quite often encountered. To cope with the extreme temperatures at stopover points in Africa, Imperial Airways advised its passengers to take the opportunity to purchase topees, or sun helmets, from the local traders. A lady passenger travelling to Durban aboard Castor in 1937 kept a journal of her experiences, including the overnight stops and the very early departures from them:

The Imperial Airways Short S.23 G-AETX being worked on outdoors at Rose Bay, Sydney, while the new hangar takes shape in the background. (Qantas Heritage Collection)

A Qantas promotional photo of the interior of the passenger compartments of the Short S.23 Empire-class flying-boat. (Qantas Heritage Collection)

Imperial Airways encouraged its captains to leave the flight deck to converse with their passengers at suitable times. During the Coronation of King George VI on 12 May 1937 Captain Powell joined his passengers on the promenade deck of Courtier to propose the Loyal Toast. Then, along with other passengers in flight aboard Castor and Cassiopeia, they listened to the Coronation service from London on their aircraft’s wireless sets. In its publicity material Imperial Airways described its C-class flying boats as providing ‘the most effortless and luxurious travel the world has ever seen’. The airline was particularly proud of its patented ‘Imperial Airways Adjustable Chair’, describing it as ‘by far the most comfortable chair in the world, an exclusive to Imperial Airways’ and declaring that ‘at the touch of a power-operated lever, without leaving your seat you can adjust these wonderful chairs from a ‘sit-up lunch table’ position to a reclining afternoon-nap position’. Another feature of the chair was its ability to double up as a life-preserver if the worst happened. Much was made of the flying boat’s advertised cruising speed of 200mph, although in service this proved to be nearer 145mph. The heating system was not particularly efficient, and few crews could master the art of getting it to perform properly. Passengers complaining of the cold at cruising altitude were issued with blankets and foot muffs. The Empire flying boats were prone to taking on water, and before each flight an engineer would go around each rivet line, tightening up where necessary and coating it with beeswax to make it more watertight.

During 1937 a survey flight to Singapore was made in preparation for the extension of the route network through to the Far East. On a more sombre note, the year was also marked by the loss of three flying boats in accidents. In addition to the previously mentioned loss of Capricornus, Courtier