Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

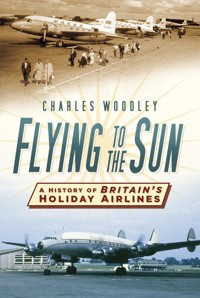

The end of the Second World War not only brought peace to a war-weary population but also delivered a plethora of surplus transport aircraft, crew and engineers, which could be easily and cheaply repurposed to 'lift' the mood of the British population. The dream of sun-drenched beaches in exotic places suddenly became a reality for thousands of pioneering tourists taking advantage of the air-travel revolution of the 1950s. From their humble beginnings flying holidaymakers to campsites in Corsica in war-surplus Dakota aircraft to today's flights across the globe in wide-bodied Airbuses, Flying To The Sun narrates the development of Britain's love-hate relationship with holiday charter airlines. Whilst many readers today will be more familiar with names like Ryanair and Easyjet than Clarksons or Dan-Air, this charming book serves as a fond reminder of those enterprising airlines and companies that ushered a new age of travel.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 272

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many people have assisted me in the preparation of this book, providing images and permission to reproduce historical data, anecdotes or simply encouragement. These include: Dave Thaxter, Andrew Reid, Nick Savage, John Camm, Clare Hunt at the Southend Museums Service, Ralf Mantufel, Klaus Vomhof, Dietrich Eggert, Dick Gilbert, Hazel at the Monarch Airlines Press Office, Peter Brown, members of the Homage to Court Line online forum, Claire Borgeat at the Thomson Press Office, Graham M. Simons, Amy Rigg and all the team at The History Press, and my wife Hazel.

I have made efforts to identify and credit the owners of all images used, but to anyone I may have overlooked I offer my sincere apologies and thanks.

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Britain’s Holiday Airline Industry: A Historical Overview

2 The Relevant Legislation

3 UK Holiday Charter Airports

4 Pioneering Days

5 The Struggle to Become Established

6 Into the Jet Age

7 Vertical Integration

8 ‘Seat-only’ Operations

9 The Long-haul Market

10 Transatlantic Services

11 Niche Operators

12 The Situation Today

13 The Low-cost Airlines

Appendix 1 Major Aircraft Types Operated by Britain’s Holiday Airlines

Appendix 2 Principal Charter Flight Operators to Palma in 1960

Appendix 3 UK Charter Airline Names to Disappear During 1989–98

Appendix 4 Tour Operator/Charter Airline Alliances

Appendix 5 UK Charter Airlines Fleets and Total Seat Capacity by Type

Sources

Colour Plates

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

The return of peace after the Second World War saw the war-weary population of Britain craving for a way to exchange their austere surroundings for a sunlit beach in a new country, if only for a week or two.

The cessation of hostilities resulted in the demobilisation of large numbers of RAF aircrew and engineers and the disposal of hundreds of war surplus transport aircraft at knockdown prices. The combination of these factors led to the formation of many charter airlines in the late 1940s and the first inclusive tour packages to destinations such as the south of France. These were only for the well-heeled, but in 1949 Vladimir Raitz began offering holidays by air to tented accommodation in Corsica, and the public responded with enthusiasm.

Holiday destinations such as Majorca and Benidorm grew from little more than fishing villages, and the UK charter airlines also benefitted from the operation of holiday charter flights out of West Berlin, an activity denied to German airlines by a post-war ban.

Many new UK operators sprang up in the 1950s, but most of these had insufficient financial resources to survive beyond their first one or two summer seasons. A particularly bad year for the charter industry was 1961, when the collapse of several of its contracted airlines (with the resultant knock-on bad publicity) led the prominent tour operator Universal Sky Tours to set up its own in-house airline, Euravia (later to be renamed Britannia Airways).

Even a financial tie-up with a major tour company was no guarantee of security for a holiday airline, and in 1974 Court Line Aviation was brought down by the collapse of the Clarksons Holidays Group. Those operators who did survive showed great resourcefulness in finding ways to circumvent the government restrictions imposed on them. ‘Flight-only’ arrangements, which included ‘throwaway’ vouchers for rudimentary accommodation in hostels or even tents, found a ready market, and entrepreneur Freddie Laker eventually secured approval to undercut the scheduled service fares to North America with his Skytrain no-reservations flights.

In more recent times, large sums of money have been invested in fleets of brand new aircraft as state of the art as those of the national carriers, and a new market for long-haul holidays has been exploited.

Within Europe, the role of the charter airlines has today largely been displaced by the activities of low-cost carriers such as easyJet and Ryanair, but I hope this book will serve as a reminder of days past and a fitting tribute to those entrepreneurs who brought about a travel revolution.

Charles Woodley

Aberdeenshire

1

BRITAIN’S HOLIDAY AIRLINE INDUSTRY: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

In 1938 legislation was introduced entitling workers in the UK to one week’s paid holiday each year, but at that time overseas travel was still beyond the means of all but the ‘leisured classes’, and the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 put thoughts of travel for pleasure on hold for the next five or six years.

The return of peace in 1945 saw the return to Britain of thousands of service personnel who had been sent to continental Europe and Asia, and who were keen to experience more of the world and escape for a while from the rationing and drabness of post-war Britain.

The rundown of the RAF in the aftermath of the ending of hostilities released into civilian life a large number of aircrew and aircraft engineers who hoped to continue in aviation as a living. Many of these saw an opportunity to set up their own charter airlines using some of the hundreds of war surplus transport aircraft that were being disposed of at knockdown prices to carry holidaymakers to the sunshine and beaches of the south of France, Italy and Spain.

To do this, they needed to establish a working relationship with a travel agent who could arrange the necessary accommodation and sell the package to the public. One of the first to see the potential for overseas holidays by air was Vladimir Raitz. In 1949 he was a 27-year-old, working for the Reuters news agency when he was invited by a friend to take a vacation at his friend’s Club Olympique, a tented holiday village on a beach at Calvi in Corsica. At the end of his stay, Mr Raitz was offered the chance, with some colleagues, to purchase a concession on a large area of beach nearby, and he seized on the idea of operating holidays to it by air.

At that time Calvi possessed an airstrip built by US forces during the Second World War, but it had no airport buildings and there was no direct air service to it from the UK. On his way back from Calvi, Mr Raitz made a detour to take a look at the Spanish island of Majorca, which also had an airfield and was served by flights from Barcelona. Although impressed by the tourist potential of the island, he decided to concentrate his initial efforts on providing holidays to Corsica.

On arrival back in London he made enquiries about chartering an aircraft for a series of flights to Calvi. He was quoted a price of £305 per round trip for a thirty-two-seat Dakota aircraft, but was also warned that he was unlikely to be granted the necessary government approval for the flights as the state airline British European Airways held a monopoly on all British air services to Europe. The fact that they did not operate to anywhere near Calvi was irrelevant. Undeterred, he set up a holiday company called Horizon Holidays, using money left to him by his grandmother.

In March 1950 he was informed by the Ministry of Civil Aviation that approval had been granted for the charter flights, but only for the carriage of students and teachers – a restriction that was to be dropped in later years. Horizon Holidays hastily produced its first holiday ‘brochure’ (in reality a four-page leaflet), offering tours to Calvi for a package price of £32 10s 0d, flying from the UK and staying in tented accommodation with meals and wine included. Great emphasis was placed on the plentiful quantities of food on offer, as Britain was still in the grip of meat rationing at that time.

In due course, tours to Majorca followed, bringing the first summer tourism to an island which had achieved a degree of fame as the winter retreat of Chopin and George Sand, and had relied primarily on winter tourism until 1951. The airfield at Son Bonet was expanded to cope with the additional traffic and, in May 1953, the UK state airline British European Airways inaugurated twice-weekly scheduled services from London, using twenty-seven-seat Vickers Vikings flying out of the RAF base at Northolt while Heathrow was under reconstruction. A refuelling stop at Bordeaux was necessary, and the fare was £39 3s 0d return.

Elsewhere in Spain, today’s major resorts were yet to be discovered by foreigners. In 1950 Benidorm was a small coastal fishing village with a grand total of 102 hotel rooms. The newly appointed mayor, Pedro Zaragoza Orts, had noted the growth of tourism in northern Europe. Recognising the tourist potential of his location, he set about developing the facilities. He arranged for running water to be piped to the village from 10 miles away, and then contacted all the major European scheduled airlines. As a result, tourists began to arrive in increasing numbers.

One problem that arose concerned beachwear. The bikini was banned in staunchly Catholic Spain, but from 1953 Mayor Zaragoza permitted it to be worn on the beaches of Benidorm. The backlash was immediate and drastic. The Civil Guard escorted bikini wearers off the beaches, and the mayor was threatened with excommunication from the Catholic Church. Undaunted, he travelled by motor scooter all the way to Madrid to see the ruler, General Franco, and was accorded his backing.

Tourist travel to Spain was still in its infancy in the early 1950s, and British citizens still had to obtain an expensive visa to enter the country. A 1952 newspaper survey revealed that only half of the UK population took any kind of holiday, and of these only 3 per cent travelled abroad.

A 1949 advertisement for BEA’s inclusive air holidays. (Via author)

A view of the Benidorm beach scene around 1964. (Via author)

The beach area at Benidorm around 1965. (Via author)

In 1954 the runway at Palma’s Son Bonet Airport was extended and a parallel taxiway and parking apron were added to cope with the growing number of tourists arriving by air. However, by 1956, landing on the 4,920ft-long (1,500m) runway was still a job for expert pilots as the approach was made through mountains, and a stone wall and some orange trees rendered the first 650ft (200m) of it unusable.

From 1 January 1954 the Sir Henry Lunn travel agency chain had been offering credit facilities in connection with its continental holiday programme, but between 1955 and 1960 the increase in UK average weekly earnings (including overtime) far outstripped the rise in retail prices. There was now the possibility of developing winter holiday programmes to areas such as Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco, and of offering affordable holidays to Madeira and the Canary Islands, which until then had only been the playgrounds of the wealthy.

During the summer of 1957, British European Airways (BEA) obtained about 14 per cent of its revenue from the ‘inclusive tour fares’ available to travel agents using its scheduled service flights to create holiday packages. In the financial year 1955–56 the independent airlines had earned some £365,000 from the operation of inclusive tour charter flights, but this was a small proportion of their total revenues of around £17 million. By far their biggest money earner (£6.725 million) was the operation of trooping flights to British Army bases in the Middle East and Singapore. This was about to change, however, as the overseas military presence was run down and holiday charters expanded, and not only from UK airports.

Since the end of the Second World War there had been a ban on German airlines operating services out of West Berlin. All scheduled and charter services were reserved for aircraft of the ‘occupying powers’ (the USA, Great Britain and France), and the UK independent airlines secured lucrative contracts from major German tour operators for charter flights to the Mediterranean resorts. This work was to expand and continue well into the era of wide-bodied jets.

Majorca’s original airport at Son Bonet was no longer able to cope with the increased volume of traffic and was unable to be extended, so in 1958 Spain’s National Airport Plan proposed the construction of a new large commercial airport at Son Sant Joan to serve the island. This was opened on 7 July 1960, and during that year around 150,000 passengers were carried into and out of Palma by UK scheduled and charter airlines.

The growth of the charter airlines attracted scrutiny from shipping lines anxious to diversify into air transport now that their traditional market was being eroded by scheduled air travel. Many of them acquired substantial financial interests in the independent carriers during the 1950s and early 1960s. During 1960, 2.25 million Britons holidayed abroad and in the summer of 1961 UK holidaymakers comprised the majority of visitors to Majorca, but even so most of the population still stayed loyal to resorts such as Blackpool instead of venturing abroad.

The year 1961 was a black one for the charter airlines, with the demise of Overseas Aviation, Air Safaris, Falcon Airways and Pegasus Airlines, all based at Gatwick and nearly all undercapitalised and thus ill-equipped to deal with the slump in traffic during the winter months. By the summer of 1962 the remaining companies were also having to compete with foreign charter airlines such as Italy’s SAM and the Spanish carrier Aviaco, both of which were the charter subsidiaries of their countries’ state airlines.

In the mid-1960s travelling abroad by air was still something of a novelty to a lot of people in Britain, and, unlike today, many holidaymakers wore their Sunday best for the flights. From 1963 the Biggin Hill Air Fair was held at the famous Battle of Britain airfield in Kent each May, and a variety of charter airlines made aircraft such as the Douglas DC-6B, Caravelle and BAC One-Eleven available there for the public to queue up to inspect inside and out. There were even short pleasure flights in such typical holiday charter airliners, all geared to overcoming any doubts about holidaying overseas by air.

One of the most popular revenue earners for the tour operators and independent airlines at this time was the operation of day trips by air to the Dutch tulip fields from airports around the UK. Most of these were organised by the newly established Clarksons Tours, whose meteoric growth and dramatic collapse would later shake the travel industry. In April 1966 a day trip from Bristol to the tulip fields cost £9, and included flights to Rotterdam and back in a Dakota aircraft of Dan-Air Services and coach travel from there to Keukenhof, with brief stops at Delft and The Hague.

By 1969 the renamed Clarksons Holidays Ltd had become Europe’s largest low-cost inclusive tour operator, and had sparked off a price war by offering fourteen nights’ full-board accommodation in Majorca and flights from the UK for £50, and taking an allocation of some 6,000 of the 10,000 or so hotel beds available in Benidorm.

It was around this time that Clarksons, in conjunction with local agent Gold Case Travel, and the Newcastle Evening Gazette, organised a ‘Holiday Spectacular’ on a mid-January evening at Teesside Airport. They expected around 2,000 people to attend, but in the event over 15,000 queued patiently to look around the interiors of a Dan-Air Comet 4 and BAC One-Eleven on the tarmac.

The public’s appetite for overseas travel was no longer confined to Europe and the Mediterranean. At the end of 1965 the first ever programme of charter packages to the USA was unveiled, featuring flights by Caledonian Airways. By 1971, however, the UK was heading into a recession which was exacerbated by high unemployment and industrial action. This included a postal strike which played havoc with the processing of travel documents and payments.

Britain’s support of Israel during the Arab–Israeli War of 1973 led to an Arab embargo on oil from the Arab states that slashed the UK’s supplies by 40 per cent. Fuel prices soared, and tour operators were forced to impose fuel surcharges on the published price of holidays. Industrial action by miners caused the declaration of a State of Emergency on 13 November 1973, under which a three-day working week was imposed in order to preserve coal stocks used to generate electricity.

In 1974 airlines using UK airports were restricted to an allocated amount of fuel each month. When the Italian charter airline SAM used up its entire January allocation in three weeks its request for additional supplies was refused. In retaliation the Italian Government banned charter flights to Italy by British carriers. One of the first to feel the effect of this was Dan-Air at Gatwick, where around 100 passengers waiting to board were told that their flight had been cancelled.

As a result of all this chaos, bookings for overseas holidays slumped by 30–40 per cent, and many tour operators and charter airlines went out of business. Further problems were faced by passengers on holiday charter flights in the mid-1970s, as a series of industrial disputes involving Spanish air traffic control staff led to closures of Spanish airspace for up to seventy-two hours at a time, and in 1974 Clarksons Holidays and its airline, Court Line Aviation, suddenly ceased operations. Some sources later estimated that in the five years leading up to the collapse some 8 million holidays had been on offer at an average of £1 below cost price.

By 1975 many UK residents had acquired timeshare apartment accommodation in Mediterranean resorts and so they did not need to buy holiday packages that included a hotel stay. However, the regulations required the inclusion of accommodation in tour prices. To get around this rule, the tour operator Cosmos introduced ‘cheapies’ holidays to Greece for £59, the price including charter flights and a throwaway voucher for very basic hostel-type accommodation, often in shared rooms without hot and cold running water. In the years to come ‘seat-only’ sales would become big business for the tour operators, and by 1988 around 20 per cent of charter flight passengers would be travelling on this basis.

In the late 1980s another price war erupted as the major tour operators hired more and more aircraft and flooded the market with holidays. In the ensuing battle for market share, price discounting became the norm. During 1987 and 1988 four new charter airlines began serving the inclusive tour market, despite there already being more than a dozen established carriers. In 1989 the top thirty British tour operators made a collective loss, leading to cutbacks in their flight programmes.

From 1990, however, the situation improved, and by 1993 the overall inclusive tour market had increased by 10 per cent, with over 13 million passengers being carried that year. In an effort to improve their year-round utilisation and tap into new markets, many of the independent airlines diversified into scheduled service operations, but this proved a costly exercise and the collapse of major carriers such as Dan-Air Services and Air Europe caused the others to rethink and curbed any further expansion in this direction.

By the summer of 1994 UK charter airlines were carrying 40 per cent of the EU total, with the most popular route still being London–Palma. For the summer of 1998 a dozen or so UK airlines were operating more than 150 aircraft, representing some 36,000 seats. The daily utilisation of each aircraft averaged over twelve flying hours, and this productivity, coupled with some of the lowest employee costs in Europe, made British charter airlines the envy of their continental European rivals.

By 1998 the continued growth in scheduled services by British Airways and its franchisees made it virtually impossible for the holiday charter airlines to obtain additional landing slots at the major UK airports at sociable hours. The only way they could carry more passengers was to introduce larger aircraft onto existing services. The following years were to see the introduction of types such as the Airbus A300 and the Boeing 757, which could not only carry more passengers to the main Mediterranean resorts but could also be used on long-haul routes to North America and the Far East.

During the year 2000 the largest UK charter airlines, in terms of passengers/kilometres flown were: Britannia Airways (21,747 million), Airtours International (18,750 million), Air 2000 (17,950 million), JMC Airlines (14,300 million) and Monarch Airways (13,650 million). All of these carriers were subsidiaries of, or had alliances with, major tour operators.

2

THE RELEVANT LEGISLATION

Since the early post-war years the activities of Britain’s holiday airlines and their tour operator partners have been regulated by various pieces of government legislation, the earlier examples of which were introduced to safeguard the interests of the state-owned British European Airways (BEA). In later more liberal years, legislation was used to protect the interests of the consumer in the wake of the financial collapse of several major tour operators and independent airlines.

The Civil Aviation Act of 1946 reserved all air services within the UK, and from the UK to Europe, with the exception of one-off ad hoc charter flights, for BEA. If an independent airline wanted to operate a regular series of flights to a destination it had to do so under a BEA Associate Agreement, which BEA would only grant if it considered the route to be one which posed no threat to its own scheduled services, even if these did not operate to the proposed destination or anywhere in the vicinity.

However, there were loopholes to be exploited. The Act only applied to single-destination routes, so the independent airlines could operate ‘aerial tours’ to two or more points without an Associate Agreement. Thus, tour operators could devise and sell two-centre tours which combined such destinations as Majorca and the Costa Brava. The Act also did not encompass tours organised for members of closed groups and sold to them via organisations such as the Royal Automobile Club.

One of the first tour operators to develop this market was Whitehall Travel, set up to offer holidays to British Civil Service staff and their families. Its founder, George Wenger, explained in its first brochure:

Whitehall Travel has been formed by a group of Civil Service staff associations with the aim of providing holidays abroad at the lowest possible cost to their members. By keeping the overheads to a minimum, by private charter of aircraft, and by fullest use of bulk facilities it has been possible to offer members better value for their money than they could obtain through any commercial agency. The only means of reducing the cost of air travel is by chartering complete aircraft, but the Civil Aviation Act forbids members of the general public from taking advantage of such facilities. The various organisations of the National Staff side of the Civil Service are considered closed societies for the purposes of the Act, and permission has consequently been received to make private arrangements with one of the best known charter companies. The terms agreed upon are extremely favourable.

Another major user of this loophole in 1959 was Milbanke Tours. The Air Transport Advisory Council (ATAC) had refused them permission for a series of inclusive tours to Palma, Perpignan and Nice, using aircraft of Hunting-Clan Air Transport. Milbanke Tours advised their potential customers that if they all joined the International English Language Association they could still book their holidays, as Milbanke was the official booking agent for that organisation and they would then be members of a closed group. An irate Ministry tried to bring a prosecution, but this was thrown out by Feltham magistrates and the tours were permitted to go ahead.

The ATAC was set up in 1947 to consider licence applications from the independent airlines. Under its terms of reference it was intended:

… to reduce the cost of air transport to the taxpayer and to give greater opportunities for private enterprise to take part in air transport developments, without in any way impairing the competitive strength of the Corporations’ international air services.

In practical terms, at that time no independent airline was permitted to operate ‘regular’ air services (as opposed to one-off, ad hoc charter flights) except under a BEA Associate Agreement. These were only granted for routes which BEA considered too unprofitable to operate with its own aircraft.

In 1952 the newly elected Conservative government laid down new terms of reference for the ATAC, under which it was to consider applications from the independent airlines for the operation of programmes of inclusive tour charter flights, provided that such air services did not ‘materially divert’ traffic from the state airlines, and to consider applications for ‘the operation on any route of vehicle ferry services, which could also carry a limited number of incidental passengers’. A BEA Associate Agreement would still be needed for journeys that amounted to ‘a systematic service operated in such a manner that the benefits thereof are available to members of the public’.

Travel agencies, and the charter airlines they used, soon learned to make their flights ‘non-systematic’ and/or only available to closed groups, thus avoiding the need to apply for Associate Agreements. One of the pioneers of such tour programmes was Horizon Holidays, which initially only carried parties of students, nurses and teachers.

In its annual report for 1954–55 the ATAC observed that:

The general outcome of the hearings and the recommendations of the Council was that a much greater number of inclusive tour services were approved by the Minister than in previous years. The Council are convinced that the traffic which will for the most part be carried on these services will not be traffic which BEA would ordinarily carry, or which would in other circumstances travel by air at all. They consider that these services should be of value in stimulating the interests of new sections of the public in air transport and that they may therefore in the long run prove to be of indirect benefit to the Airways Corporations. For the most part, inclusive tour services were recommended for operation in 1955 only, although this was not intended in any way to prevent companies from submitting fresh applications for similar services in later years. It may prove possible, when further information is available from traffic figures for the summer of 1955 about their effects on the normal scheduled services of established operators, to approve inclusive tour services for slightly longer periods than hitherto.

In 1956 the ATAC dealt with 428 applications.

In its 1956–57 annual report BEA said:

We informed the ATAC in 1955 that we would not oppose applications from the independent operators for inclusive tour services at weekends during the summer months. The volume of these services to the main Continental holiday centres has, however, now grown far beyond the scale which could be regarded as economically helpful in dealing with peak traffic demands. The size of the problem is reflected by the proportion of the total summer traffic between the United Kingdom and the Continent carried by independent operators on inclusive tour services. In the summer of 1956 they carried 27% of the total air traffic to Spain, 15% to Switzerland, 17% to northern Italy, 18% to France (excluding Paris), and 21% to Munich and Austria. In our view these operations have caused material diversion of the traffic from BEA’s services.

In its 1958–59 annual report, BEA said, ‘We cannot afford to be excluded from the cheap holiday market’, and complained of the diversionary effect of inclusive tour flights operated by the independent airlines. BEA said it was ‘imperative’ that the corporation should recover its position in this ‘most rapidly growing sector of European air travel’. Accordingly, they urged through the International Air Transport Association, a measure whereby they could cut fares on scheduled services to the prime holiday resorts, so that they could offer reductions of up to 25 per cent for the summer of 1959 to travel agents using their services as part of their package tours.

THE UK TRAVEL ALLOWANCE

Concerned about the possible loss to the Exchequer of sterling being converted to foreign currencies and spent overseas by holidaymakers, the UK Government has traditionally limited the amount that can be used in this way. The personal allowance has fluctuated over the years since the end of the Second World War, from £100 in early 1951 to £50 in the autumn of that year, then to £25 in January 1952, up to £40 in the 1953 Budget and gradually upwards again until it was increased to £100 in October 1954.

A sterling crisis in July 1966 led to a reduction to £50 in the form of traveller’s cheques, plus £15 in cash (intended for use only when the traveller returned to the UK). On 18 November 1967 the government was forced to devalue the pound by more than 14 per cent. Among other things, this led to the introduction of the so-called V Form. Tour operators had to declare on this the cost of the overseas ground elements paid for in foreign currency, and this amount was deducted from the traveller’s £50 allowance. In the early 1970s the foreign travel allowance was increased to £300.

AIR TRANSPORT LICENSING BOARD

In 1959 the Ministry of Aviation was created as part of the break-up of the Ministry of Supply. The 1949 Civil Aviation Act was repealed, and in 1960 the Civil Aviation (Licensing) Act was introduced. The Air Transport Advisory Council was abolished, and in its place came the Air Transport Licensing Board (ATLB). It had a brief which included ensuring easier access to routes and licences for the independent airlines.

In 1960 UK airlines needed to apply to the Director of Aviation Safety for an Air Operator’s Certificate (AOC) before they could carry fare-paying passengers, and they also had to apply to the ATLB for a B Licence for inclusive tour charter flights. The application was made in conjunction with the relevant tour operator or travel agent, and covered a regular series of flights for the exclusive carriage of passengers on a specified holiday. The licence usually had provisions regarding the cost of the holiday, and licences were issued after having considered the fitness of the tour operator (in particular, the financial fitness).

The ATLB also looked into the operator’s insurance arrangements, and even the conditions of service of its employees. The first large batch of inclusive tour licences was issued at the beginning of 1962, but the board usually rejected far more applications than it granted.

However, as tourism to France, Italy and Spain boomed, these countries and others formed their own charter airlines. The ATLB was hard pressed to refuse them traffic rights, as it knew that the governments of these carriers would probably take retaliatory action against British airlines. If a tour operator had its joint application with a UK charter airline turned down, it would then contract its flights out to a foreign carrier, knowing that this application would then be approved. During 1962 the foreign airlines’ share of the UK inclusive tour market increased by one-third.

PROVISION ONE

Until 1968 the minimum package holiday price was not allowed to undercut the scheduled service fare charged by BEA for the route in question. This piece of legislation was known as Provision One, and was there to protect the revenue of the state airline, although there were certain exceptions for flights to the more distant European destinations.

For 1969, however, the government permitted the tour operators to set their prices at the 1968 levels, effectively allowing a decrease in prices in real terms. Again in 1971, the minimum summer tour prices were allowed to be pegged at summer 1970 levels, but by then the pressure for a change in the legislation had subsided somewhat anyway, as the independent airlines had begun to fear that lower overall tour prices would lead to demands from tour operators for lower charter rates at a time of overcapacity in the charter market.

In 1971 the government announced that the Provision One minimum price restriction would be lifted for the winter of 1971–72 on holidays of seven nights or less, and in October 1972 Provision One was abolished completely.

INCLUSIVE TOUR EXCURSION (ITX) FARES

In the 1960s, in order to be able to compete with charter flights on their leisure routes, ITX fares were offered by the scheduled airlines belonging to the International Air Transport Association (IATA). These could only be used by IATA-appointed travel agents and tour operators to construct package holidays using scheduled flights. The fares for individual travellers were roughly 75 per cent of the public excursion fare, dropping to around 65 per cent for groups of fifteen or more using night flights.