28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

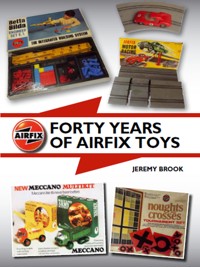

Airfix acquired the first plastic injection moulding machine in the U.K. in the mid 1940's and was soon manufacturing vast numbers of plastic toys. By 1981, when Airfix's financial woes led to takeover and the end of all production save for plastic model kits, it had made a wide variety of toys, games, arts, crafts, building sets, racing sets, model trains and even Meccano and Dinky toys. Profusely illustrated with over three hundred photographs, Forty Years of Airfix Toys gives the full history of the Airfix toy range including year-by-year listings of all the toys sold by Airfix; logs and packaging; Airfix's magazines and a full listing of Airfix pattern numbers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 496

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

FORTY YEARS OF AIRFIX TOYS

JEREMY BROOK

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2019 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© Jeremy Brook 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of thistext may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 536 7

Contents

Foreword

Introduction and Acknowledgements

1A Brief History of Airfix

2Toys and Games

3Building Sets – Betta Bilda

4Motor Ace/MRRC

5Arts and Crafts

6Meccano and Dinky Toys

7Railway System and GMR

8Miscellaneous Toy Ranges

9Logos and Packaging

10Airfix Magazines

11Pattern Numbers

12The Other Airfix

Index

Foreword

On joining Airfix in the early 1960s as a Design Draughtsman who had never built an Airfix kit, the design of the models and the ethos of John Edwards, the Chief Designer, intrigued me. The ‘watchword’ was attention to detail and double-check your source. Having survived the demise of Haldane Place, the home of Airfix, and opened the Palitoy Design Office, the ethos remained but we became restricted by costings.

Peter Allen in 2018. PETER ALLEN

I have known Jeremy for many years and in Forty Years of Airfix Toys he follows the ethos of John Edwards.

PETER ALLEN

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Airfix Products Ltd was the Toy Division of Airfix Industries. Following World War II, its main output was to be of toys and games, with some household products also being made. As the first operator of a plastic injection-moulding machine in the UK, it would become the country’s biggest producer of plastic combs and manufactured a growing range of plastic toys. In 1952 it began work on its first plastic construction kit, a small model of the Golden Hind. The newly formed Kits Division would go onto becoming the largest and best known manufacturer of plastic kits in the country, and still to this day is introducing new models each year.

The toys and games side of Airfix carried on making toys, games and building sets and, at the beginning of the 1960s, it entered the motor racing market as a competitor to Scalextric while its early building sets were improved and relaunched as Betta Bilda to better compete with the improved plastic Lego. Painting sets were made available when Airfix repackaged the American Craft Master range, and later it also developed its own ranges of arts and crafts.

Early 1960s Toy Catalogue.

In 1971, Meccano and Dinky Toys were purchased from the Lines Brothers group which had recently gone into liquidation, and the ailing Tri-ang Pedigree Company also joined Airfix a few years after. In 1976, a new range of high-quality train sets and accessories were released that were worthy rivals for the existing Hornby railways. Around the same time, the company acquired the small manufacturer Scalecraft, which made a range of plastic, motorized kits. By the late 1970s, in short, Airfix was producing a large range of toys and model products that are often overlooked because of the success of its famous plastic construction kits, which are still in production today sixty-five years after the first kit was released and nearly forty years after the original Airfix company ceased trading. Details of those can be found in my book 60 Years of Airfix Models.

This is the story of those ‘other’ toys and models produced over the forty or so years of the life of the original Airfix Company.

Acknowledgements

It has been a great pleasure to write my second book on the Airfix story. While I have a lot of Airfix toys in my collection, this book would not have been so comprehensive without the help of many people. Ralph Ehrmann, who was managing director of Airfix, and Peter Allen, who worked at Airfix and later at Palitoy, both have fantastic memories and were able to answer all the questions I had, the answers for which are not available elsewhere. My thanks to Graham Westoll, who worked in the Arts and Crafts division and wrote several articles for Constant Scale, which provided much insight into the workings of the non-kit parts of Airfix, and Graham Short, who over the years sent me numerous photographs of Airfix toys from his huge collection. Arthur Ward, who has written several books on Airfix, including his 2013 The Other Side of Airfix, provided much background information on the workings of the toys side of Airfix, and Jo May-Prussak, who revealed much about the life of Nicolas Kove. Paul Morehead of PlasticWarrior had much information on the early days of Airfix, and John Begg, an avid collector, allowed me to photograph much of his impressive collection.

Thanks go also to all the many members of the Airfix Collectors’ Club, who encouraged me over the years to complete this important part of the Airfix story, and finally to my grown-up children, who understood their father’s need to buy dolls and the like on eBay!

LMS Royal Scot Locomotive.

Motor ACE – the ‘Hi Speed’ range.

CHAPTER ONE

A Brief History of Airfix

In 1938, a Hungarian Jew by the name of Miklos Klein arrived in Britain, whereupon he changed his name to Nicolas Kove. He had led an interesting life, having been sent to Siberia in World War I before apparently walking back home! Between the wars he moved with his family to Spain, where he set up a company employing cellulose-based plastics and patented a process for stiffening collars called ‘Interfix’. With the threat of civil war in Spain looming, he moved to Italy, but found that Mussolini’s strong connections to Hitler made Italy an unsafe base for a Jewish-run company. So he took his family and set off for a safer home.

The story of Airfix starts with his arrival in England. Shortly after arriving, he set up a new company, probably in 1939, in the Edgware Road in London. He called his new company ‘Airfix’, which had nothing to do with aircraft models; the famous kits would not appear for another fourteen or so years. He chose the name ‘Airfix’ because he strongly believed that a successful company should appear at the front of an alphabetical trade directory and he also had liked trademarks ending in ‘ix’, like he had used for his collar-stiffening process in Spain. Since one of his earliest products was to be air-filled toys, he felt ‘Airfix’ was appropriate since his product could be said to be ‘fixed with air’.

The war then intervened and, despite his being a Jewish businessman, effectively a refugee, Kove is believed to have been interned on the Isle of Man for a short while. During the war he benefited from several contracts associated with the war effort, but after the war, like many others, he found materials were in very short supply and so he had to resort to finding materials wherever he could, even grinding down old fountain pens to produce plastic for his injection-moulding machines. He had been manufacturing utility lighters designed by his son-in-law during the war, but was always on the lookout for new markets and ways to keep his hungry machines busy. By now the company logo read ‘Airfix Products in Plastic’, to reflect his growing dependence on plastic toys and articles.

The head office of Airfix was at 24–26 Hampstead Road, London NW1 and the factory was at 8–9 Spring Place, Kentish Town, London NW5.

The Airfix factory in the 1940s. JOHN DOLAN

Around 1947, he happened upon a new market. Windsor’s had just produced the first plastic injection-moulding machine in the UK and were looking for someone to operate it. Islyn Thomas of Newark, USA, who ran Hoffman Tools and would supply Kove with his first mould for combs, was to introduce him to Windsor’s. This fusion of needs resulted in Airfix operating the first plastic injection-moulding machine in the country and would, consequently, make Airfix the most important plastic moulding company in Britain in the late 1940s.

At that time combs were made of acetate and the teeth were cut using saws. Utilizing the moulds supplied by Hoffman Tools, Kove could provide combs made out of plastic, which were much stronger and cheaper than the old acetate ones. The managing director at Airfix before 1950 was John Dolan. He said that Airfix was producing combs at a rate of forty-two gross (144) a shift and was selling them for £5 per gross, which made for an income of £210 per shift with a selling price of 8d (3p) a comb. Kove ran three shifts a day, and he told Dolan that, ‘In Hungary we drive them with whips!’ Within a short while, Airfix was the largest manufacturer of combs in the UK and controlled and dominated the market. So keen was Woolworths, its principal customer, to get their combs that they frequently picked them up from Airfix rather than wait to have them delivered! According to Dolan, Airfix was literally making money hand over fist and was able to buy the Kentish Town factory for £12,000. Eighteen months later, Airfix was still making combs and now had six 3oz injection-moulding machines. They had a 25-second cycle time on them; combs came out of the machine limp and dropped onto a steel slab to make them set solid. ‘The spivs were lining up on the pavement; you couldn’t buy a comb in the shops’, commented Dolan.

By the early 1950s, however, Airfix was facing increasing competition from other comb-making manufacturers, with the likes of Aberdeen Combs and Halex, part of British Xylonite (BX Ltd), entering the market. Interestingly, British Xylonite had another subsidiary, Cascelloid, which made toys and was located at Coalville, Leicester, where it would later trade as Palitoy. In 1968, Palitoy was bought by General Mills, which later bought Airfix from the receivers in 1981! So around 1951 or 1952, Airfix withdrew from the comb-making business and concentrated on its growing toy range and, of course, the exciting new kit range.

The early days at Airfix were always somewhat chaotic and it was very much a hand-to-mouth existence. John Dolan gave a very interesting and illuminating interview to the Plastic Historical Society in the late 1990s, shortly before his death, in which he describes many of the goings-on at Airfix whilst Nicolas Kove was running it. He tells of Kove’s attempts to track down and acquire raw materials for production and of having to cut a hole in the first floor of the factory so that the injection-moulding machine could be lowered in!

Dolan claims to have invented the kitbag and header for the Ferguson tractor and later kits, although he left Airfix in 1949, around the time that the tractor was first being produced. Whilst there is cause to doubt the veracity of some of his reminiscences, he does paint an interesting picture of a typical post-war small company, struggling to survive.

Dolan joined Airfix in 1945; he then left in 1947 and rejoined, briefly, in 1949. He described Kove as a very volatile man but extremely cultured, who insisted that his family only spoke English in Dolan’s presence. When asked on tape what Kove looked like, Dolan likened Kove’s appearance to that of Napoleon in the famous painting of the retreat from Moscow.

Kove’s wife worked in the office and Dolan tells of occasions when she disagreed with Kove and he would cross the room and slap her! Despite this and Kove’s apparently fiery temper, Dolan liked him immensely. Towards the end of his life, Kove put his affairs in his wife’s name, but she predeceased him by a few weeks.

Kove reputedly had a fiery temper but could also be very generous. His health was not too good and much of the day-today running of the company was put into John Dolan’s hands, then, from March 1950, in Ralph Ehrmann’s. Airfix’s bankers, Warburg’s, had become worried about Kove’s ill-health and had arranged for a young member of their staff, Ralph Ehrmann, to join Airfix and help Kove run it. Regarding Kove’s illness, John Dolan said on his tape:

One day he phoned me up and asked me to go up to head office and he was sitting there looking really despondent; and, knowing him as I did, I thought, ‘Oh my god, what has happened now?’ So I sat down. He said, ‘Mr Dolan, I have something to tell you. I have seen the king’s surgeon, Mr Levy, and I have a cancer in the bladder. Mr Levy said that I have eighteen months to live at the most if it goes on as it is. I could have five to ten years if I have it out and an artificial bladder put in. What would you do?’ So I said, ‘There is no question about what I would do. If you die, you die under controlled conditions. I would have it out and the artificial bladder in. No question.’ And he picked up the phone and dialled Levy at the London Clinic and made the appointment there and then. He was a great gambler, by the way, and he said to me, ‘I will have a bet with you. You will bet me that I will not survive.’

‘Ok, if you want it like that, I bet you half a crown (12.5p) that you die under the operation.’

‘Good. Give me the half a crown, because I am going to win.’

And he had that half-a-crown taped into his hand. He lived about ten years after that. He put all the money into his wife’s name and she died before him. Three months later he died.

The operation was in May 1948 and Islyn Thomas and his wife came over to London and visited Kove in hospital.

John Dolan had apparently left in 1949 and Ralph Ehrmann, the young man from Warburg’s, was quite surprised at what he found. Fortunately, three months earlier, Kove had employed one John Gray as chief buyer. Gray had come from Lines Brothers (Tri-ang) so had a good understanding of Airfix’s markets. Together Ralph Ehrmann and John Gray turned Airfix around and made it into the modern company that would become a world leader in industrial packaging and, of course, toys. Nicolas Kove died in 1958 and initially his daughter, Margaret, hoped to run the company. Fortunately for Airfix, however, she was persuaded to sell her interest in the company and retired to the south of France where she became a well-known socialite. In that year Airfix became a limited company with Ralph Ehrmann at its head.

Nicolas and Clothilde Kove. JO MAY-PRUSSAK

Nicolas Kove’s grandson, Jo May- Prussak, contacted Plastic Warrior magazine in the early 2000s with information about the early days at Airfix. He had also provided me with information for Constant Scale, the journal of the Airfix Collectors’ Club. I am reproducing his email here as it gives us a better look at Airfix in the years following the war:

Regarding the Plastic Warrior publication on the ‘Early Days of Airfix’, I read it with interest as my grandfather was Nicolas Kove.

One must take what Mr Dolan says with a pinch of salt. There are inaccuracies in what he says which make it hard to know quite what is true and what isn’t. My grandfather – as far as I know – was never ‘Kovespachi’. He was born ‘Klein’ then changed his name to Koves (pronounced ‘Kovesh’), then when he came to England became Kove. However, Dolan paints a picture of Nicolas Kove which certainly rings true.

Nicolas Kove came to London from Milan in 1938 with his wife Clothilde and his daughter Margaret (who was sixteen at the time). In 1941, Margaret married Bernard Prussak, a Latvian Jew from Riga, who had also arrived in London about the same time. Nicolas and Clothilde strongly disapproved. They had me in 1944 when they were living down the road from Nicolas and Clothilde, who had a big house at 252 Finchley Road. And then in 1948 my sister Judy was born. Bernard, my father, had helped Nicolas in the very beginnings of Airfix, apparently even funding him to some extent, and also designing Airfix’s utility lighters, which were in production during the war. But they fell out. In fact, Nicolas would not speak to him until I was born. Mr Kove also fell out with my mother, Margaret, for a short time when she was working for him in the office. The Hungarians in my family had very short fuses.

Nicolas Kove died in the evening of 17 March 1958 at his home, and just three weeks after his wife, who died on 22 February. My mother, who by now was married to Bob Elliott, inherited Airfix as a major shareholder. Bob became chairman. Bob, my stepfather, was a good chap and a successful businessman in his own right. He was the E in FEB, which still makes chemicals for the construction industry. Margaret, who was herself growing a highly successful beauty clinic in Welbeck Street at this time, felt she needed to take charge at Airfix, which since 1957 had been a public company. Fortunately for Airfix, and probably my mother, Ralph Ehrmann nipped that in the bud. So my mother backed down and gradually sold off her majority shareholding to become a high-flying socialite and prolific artist in Mallorca. She eventually lost most of her fortune in a financial scandal in the 1960s, the CADCO affair, which involved a pig products factory in Scotland, the actor George Sanders, and a couple of dodgy sharks.

Ralph Ehrmann told me an interesting story which I never knew. Apparently, when Kove returned to Hungary from his Siberian escape during World War I, he was greeted like a prodigal son by his father and uncle. They were wealthy landowners, owning several villages in southern Hungary. As they had been overrun by Germans, the Russians, then Germans again, they decided to sell their land and pocket the money. So when Nicolas returned home his father said, ‘Nicolas, you’ll never have to work again. We’ve sold our land and invested it in Austro-Hungarian war bonds.’ The family were millionaires for about ten days until the government finally collapsed.

When I have spoken to Ralph he consistently emphasizes how courageous Kove was and how his drive and energy kept Airfix going. Sometimes this was infuriating, but he was undoubtedly respected. His background was one of losing everything and then having to make good again, and being on the run from hostile regimes. He was clearly a tremendous survivor, had a nose for a deal, and in fact was a very clever man. He thought very highly of Ralph Ehrmann, almost regarding him as the son he never had.

Regarding injection-moulding machines, Nicolas Kove established a friendship with Islyn Thomas, who published a book on injection moulding in plastics in the USA. Thomas introduced Kove to Windsor’s, who let him have his first machine on tick. In fact the first machines Windsor’s made were for Airfix, which meant Nicholas Kove always had a special position with Windsor’s. Ralph says they had six small 3oz machines and an 8oz Watson Stillman when he arrived in 1950.

To illustrate the point about the ‘Napoleon’ likeness, I include a photo of Nicolas and Clothilde Kove probably taken on a trip to the US – either on the Queen Mary or the Queen Elizabeth. It might have been when he went to research what the US was doing with toys and injection moulding machines, some time after 1947.

JO MAY-PRUSSAK

John Dolan remembered Bernard Prussak and related a story about him. He apparently lacked ‘people skills’ and no doubt his nationality would not have endeared him to the girls working for Airfix, post-World War II. Dolan was once asked by Kove to sort out a ‘riot’ at the Edgware Road factory because his son-in-law did not know how to handle the workers and had upset them. Dolan arrived to find the shop in a mess with acetate everywhere. The ‘foreman’, a very nice lady, explained that Bernard could not treat the girls in the way he had. Dolan then told her that they would have to clear everything up, which they apparently did.

Concertina mould from 1948. JOHN DOLAN

Violin mould from 1948. JOHN DOLAN

A 1948 publicity photo of a violin. JOHN DOLAN

Publicity shot of Woofy the Sea-Lion, 1948. JOHN DOLAN

The mould for Woofy. JOHN DOLAN

As the pioneer in plastic injection moulding in the UK, Airfix had been making a range of toys and games that were becoming increasingly popular. This expertise is probably the reason that Airfix was approached by Harry Ferguson in the late 1940s to produce a promotional model of his new TE20 tractor, which was entering production in Coventry. He wanted a made-up model that his sales force could show and give to prospective customers. However, Dolan claims that Kove approached Ferguson to try to get him to allow Airfix to model one of his vehicles! The finished tractor was to 1:20 scale and, according to Ralph Ehrmann, who had joined Airfix after the model was made, the mould was a lovely one that produced very detailed and accurate miniatures. BX provided the powder and Windsor’s and John Summers in Birmingham made the mould for the tractor, which cost £6,000; in comparison, the 1971 1:12 scale 4.5-litre Bentley mould cost £80,000! Apparently the tractor mould survived into the late 1970s, as Peter Allen, one of Airfix’s most senior designers, said that to mark sales manager John Gray’s retirement from Airfix, the workforce secretly tested and ran the mould to produce a few tractors that were then ‘bagged up’ so that John Gray could receive one as a retirement gift.

The problem was that the models had to be assembled by the Airfix workforce, which was both time-consuming and costly. Models were often returned because small parts had broken and needed replacing. This was becoming an expensive headache for Airfix. By now Airfix had gained Ferguson’s approval to sell the tractor to the general public so it was decided to sell the model as a kit of parts in a box to be assembled by the purchaser. This appears to have happened around 1952 or 1953. It was at first sold in a shallow box with the parts fitting into slots in a cardboard inner tray, similar to the one proposed for the Golden Hind. However, the problem with the boxed kit version was that if the box was turned over, the plastic pieces fell out of their slots! Later, probably around 1955, it would be sold in the standard Airfix kit package of a polythene bag with a header attached, which had been devised by Ehrmann and Gray to put the new Golden Hind into.

The Ferguson tractor is sometimes thought of as the first Airfix kit, but it was not designed as a kit but as a model assembled from parts. As such, it is probably the most important toy produced by early Airfix. The credit for being the first true Airfix kit goes to the little replica of the Golden Hind. However, the kit that more than any other will always be associated with Airfix is the Supermarine Spitfire. A somewhat crude and inaccurate model was released in 1955, coded BT-K, but it led the way to hundreds of other kits of aircraft – and indeed today the main output of Airfix is still aircraft. Whilst the kits would become what Airfix is best known for, the toys and games continued to develop, including further lines such as trains and racing sets.

Publicity photo from 1949 of the Ferguson Tractor. JOHN DOLAN

From those humble beginnings in 1939, Airfix would survive the war and then weather the difficult early post-war years to become the most important plastic injection moulding company in the UK by 1949. A move to a complex of factory buildings in Haldane Place, just off Garrett Lane in Wandsworth, in August 1950 and the decision to enter the construction kit market in late 1952 would make the name of Airfix known around the world. Whilst the kits are still in production and being added to today, sixty-five years after the first kit was made, Nicolas Kove’s original company would enjoy a just over forty-year life until it all came to an abrupt end in January 1981, when Airfix was forced to call in the receivers. Peter Allen, who had recently moved from the Design department to Marketing, gave an account of those sad days in January 1981 in Constant Scale in 2001:

In the previous two years we had seen two sets of redundancies, the debts of Meccano were increasing year-on-year, kit sales were falling. Salaries had been static for eighteen months (but not inflation!); morale was not high but was raised as a Christmas bonus was paid. Our MD, Ken Askwith, had briefed us on the need to hold spending to a minimum. No work could be commissioned without a quotation and suppliers were instructed by letter not to start a project until a purchase order was in place, his words being, ‘this is your suppliers’ safety net’. One other point he made was that for every £1 we spent, a salesman had to sell £4 of product for the company to break even, a very sobering point to make. Every purchase order raised had to be signed by him.

Haldane Place in the 1970s. AIRFIX NEWS

Haldane Place as it appeared in 2018.

The bottom of Haldane Place in 2018.

Thursday, 29 January 1981, two days before the start of Toyfair, was the date of the annual sales conference. Myself plus the rest of the marketing department, along with representatives from R&D (Kits & Toys) were at the Seven Hills Hotel for a training session to familiarize the sales team with the 1981 products.

Minutes before I arrived at the hotel, Peter Mason, our sales director, received a call from Haldane Place and left the hotel saying he had been called to a meeting. Calls to different departments of the company told us the directors were all in a board meeting, subsequent calls got us to the switchboard and we were all told all staff had been called to a meeting on the factory floor. Finally we managed to reach colleagues, who told us the company was in receivership.

When Peter Mason returned to the hotel the only good news he had was that it looked like we would be at Toyfair. So the training session started. The atmosphere at the evening dinner was obviously subdued. My last tangible memory of the company is the dinner menu scroll, tied with a red ribbon; this lives in my model cabinet. How many of these survived?

Toyfair was held at Earls Court and followed the Boat Show. The stand construction really got underway by Wednesday; this meant that with luck, either late Thursday but usually mid-morning Friday, the stand could be dressed. However, as the receivers gave stop-go, stop-go decisions, the stand construction was delayed, with the knock-on effect that we were not able to start dressing the displays until the evening. We negotiated (as we thought) with the Earls Court management for six of us to be locked in overnight to complete dressing the stand. At 1am, we were evicted by ‘Jobsworth’ and told we could come back at 7am. For me this meant getting home at 2am, leaving at 5am to call into Haldane Place to meet a couple of colleagues and pick up odds and sods that we needed on the stand. That stand opened mid-morning; it would normally have been a hanging offence to have opened Toyfair so late in the day.

The fair was not good; sales were down on the previous year. During the years that Toyfair was held in Brighton it was a selling fair, with only the trade being allowed onto the stands. In the mid 70s the fair was moved to the NEC, a disaster; from there it moved to Earls Court. Along the way the purpose of the fair changed: it became more of a vehicle to view the products, with major retailers having private previews in November/December. They would send staff to the fair to see the product line. The busy day at the fair was always Sunday, referred to by the trade as Mama & Papa Day, when the family-owned businesses came to view what was on offer.

The fair ran (and it still does) for five days, closing on Wednesday. Packing delicate models is not easy but has to be done at speed when the fair closes. The stand is demolished around you as you work. The problem we were to encounter was that although the contractors were being paid to dismantle the stand, they were not being paid to remove it for storage – where it fell, it stayed. We worked into late evening packing up all product ranges. Thursday and part of Friday saw four of us manhandling boxes of product plus all the sections of the stand and floor covering down to the loading bay, the final hassle being to get permission from the receivers for one of our own lorries to come and collect the stand.

After lunch Friday saw us back at Haldane Place, with the comment from many of our colleagues that we had been better off away from the office. Lunchtime had seen a near riot, as the receivers had not realized that the tool room and factory staff were paid weekly. No provision had been made to clear funds in time to have wage packets made up by late morning. This was made worse by the moulding shift finishing at 2pm and demanding their wages.

We had seen the company shrink, if memory is correct, from about 700 to about 500 in the past eighteen months. One thing we were sure of was that over the next few days of receivership more of us would be going.

During 1980, the London head office had been closed and the staff located to Haldane Place; these were the first to go. The only directors to remain on site were those of Airfix Products, the Toy Division (the managing director plus sales and finance director). In all, about 150 went, with all departments being affected. In R&D Toys all that remained was the department head; we lost about 50 per cent of the kit designers. In marketing we remained intact except for our director; this left us reporting to the MD.

Ralph Ehrmann in 1976. AIRFIX NEWS

Hampstead Road in 2018.

Those of us that had been at Toyfair were, I believe, the first to cross swords with the receivers when we tried to claim expenses. The till on the refreshment bar had a fault that none of us had seen. Every receipt had the same date and time. In the end they agreed we could not all be presenting receipts we had gathered up!!

Not the greatest footing on which to start working for your new (short-term) masters.

A very sad end to a great British company. They say that everyone can remember where they were when President Kennedy was assassinated. I remember where I was when Airfix collapsed. I had returned from school (I was a teacher in those days) and was just getting tea ready when I heard Airfix mentioned in the news on the TV in the other room. I rushed in to hear that Airfix had called in the receivers. I knew that things were rough at Airfix but this was a great surprise. It seemed that a part of my life had just ended. Although I had overnight lost a fair part of my savings, as I had had Airfix shares since 1971, it was the thought that Airfix might disappear that affected me most.

My own involvement with Airfix dates back to the late 1950s. When my older brother started to receive kits for presents, I was always itching to get at them. I started to make my own kits, which were almost always Airfix, largely because of their cheaper cost and better availability through Woolworth’s. Frankly, I thought the Airfix kits were much better than the competition’s and the constant scale and ‘themed’ series made them a much better bet for collecting and playing with. The toys were also mainly sold through Woolworth’s, though I was not so interested in them. For some boys it was football, cars or stamps – later, of course, trumped by girls – but my youthful obsession was Airfix, so it is perhaps not surprising that when Airfix announced its Motor Racing set in 1962, I had to have one.

It was in August 1963 that I decided to buy Airfix Magazine each month, and I also bought my first catalogue to add to the various leaflets I had picked up and fortunately not discarded. I was in the habit of carefully opening any kit and always saving the box, header and instructions. Soon I had several old kit boxes filled with bits and pieces from earlier kits. I also cut out any news items in the daily papers that was about Airfix and squirrelled them away for future reference, and if I saw any leaflets about Airfix toys I would pick them up and save them. This collecting habit would stand me in good stead when I came to run the Airfix Collectors’ Club, for I had quite an archive of all things relating to Airfix, most of it collected at the time.

In the 1950s and 1960s the main source of supply for Airfix kits and toys was the F. W. Woolworth chain of stores. In those days every town had a ‘Woolies’ and many suburbs of cities had small branches. One could always see the Airfix kits because, high above the maroon-coloured counters, were huge sheets of white pegboard to which were affixed numerous made-up Airfix kits, so one could automatically make a beeline for the Airfix counter.

Letter from Islyn Thomas of Hoffmann Tools, 1948. JOHN DOLAN

Long before the kits began to dominate the wall space in Woolworth’s stores, the store chain was the principal customer for Airfix’s other products. Woolworth’s couldn’t get enough of Airfix’s injection-moulded combs, and in the early 1950s, vast numbers of toys like the Ice Cream Tricycle were being sold off the old maroon counters. Woolworth’s was selling Airfix’s toys as fast as Airfix could produce them. In those days high-volume production was the key to profitability and Woolworth’s orders ensured that Airfix was always making lots of its various products.

Ralph Ehrmann, 8 May 2018.

The sources for most of the toys mentioned are the various leaflets and catalogues put out by Airfix over the years. In the 1940s and 1950s, trade magazines like Toys & Games also provided much further information. Airfix had also started a tooling log in the late 1940s in which every mould made by them would be recorded. By 1968, this hardcover book had become very scruffy and many of the dates illegible, so it was decided to enter all the details into a brand-new book. Later still the moulds recorded therein would be entered into computerized sheets. The original tooling log was then returned to a drawer where it languished until being rescued by Peter Allen after the receiver had been appointed. It was sold a few years ago at auction, but I managed to track down the buyer who kindly allowed me to copy it. It is extremely fragile but now it is copied it is easy to use and provides much first-hand source material. A copy is also now in the main Airfix archive held by Hornby Hobbies Ltd.

In the next few chapters I shall look at the way the range of toys developed over the forty years that the original Airfix group of companies was in existence. For each year I shall try to cover all the toys or models announced in that year. Some may have taken a couple of years to appear and some arrived in the shops unannounced, but generally most made it into the shops in the year of their announcement. Since many toys had very short lives and do not appear in any surviving records I have seen, there will be toys missing from the early years. I shall give a very brief history of most toys but a little more space to important or innovative ones. Due to a shortage of catalogues and leaflets for the 1940s and 1950s toys, I shall have to group most of the items in a five- or ten-year period.

Each model will have the Airfix number first applied to it. Initially the toys used pattern numbers taken from those used by all the other Airfix products in the 1950s. Around 1959, the kits started to use catalogue numbers, which were more specific to series and type of kit; and later toy ranges, like racing sets and railways, had special numbers allocated to each range. The main toy range did not change until the advent of computerized numbering in the early 1970s. These replaced the original pattern numbers.

CHAPTER TWO

Toys and Games

The original Airfix Company was in existence for just over forty years, and its longest-running range in 1981 was toys and games. In his book The Other Side of Airfix, Arthur Wards recounts how Ehrmann told him that although they were selling kits like the proverbial hot cakes in the 1960s and 1970s, he was never quite sure that they were not just a fad and so it made sense to keep the toy range going in case buyers began to desert the kit range. In fact, though kit sales declined in the late 1970s with the rise of computer-based games, at the time of the bankruptcy the kits were the only part of Airfix that was still consistently profitable.

The early Airfix products all used a numbering system based on the pattern number. These numbers went up to the mid-1800s, at which point a computerized number system was introduced. The kits had changed to a specific numbering system in the late 1950s, but the toys and games did not change until early in the 1970s. Since the pattern numbers were issued more or less in sequence it is possible to roughly date a particular toy or product.

By 1950, Airfix had a large catalogue of toys. I bought the John Dolan collection a few years ago and, as well as a tape recording of his 1990 interview, it included a selection of the toys that were produced in the 1940s. Also, and more importantly, there were three similar catalogues – a retail, a wholesale and an export one. They were each dated May 1949 and so it is possible to list the toys that Airfix was producing in 1949. Some of the ranges disappeared in the early 1950s to be replaced by new toys, but some, like the Ferguson tractor, soldiered on until the late 1950s. Some products are suffixed with a B, indicating a boxed item(s), or an L, indicating the item was available loose. Items sold on a card were suffixed C. Some toys were available in several formats, so for the sake of brevity I have not listed all of these options since it is the main product we are concerned with here.

1939–1949

It is not known exactly what was produced by Airfix during the war years. One reason that Nicolas Kove chose the name ‘Airfix’ was that one of his first products was making inflatable toys, so his products could be said to be ‘FIXed with AIR’. He has been credited with inventing the Li-Lo air bed that many of us used in the 1960s and 1970s on holiday. The name ‘Li-Lo’, however, was created by P. B. Cow Ltd in 1936, and registered as a trademark in the UK in 1944 and in the USA in 1947. So it is unlikely Kove invented the Li-Lo or actually produced them, although he may have been making air-filled mattresses in the 1930s. Airfix may have made inflatables for military use as it, like many other companies, fulfilled military contracts during the war. The company also made utility lighters during that period.

After the war, like many small companies, Airfix found that raw materials were in short supply and Kove had to resort to imaginative methods to get supplies. There are stories of Kove buying unwanted fountain pens so he could grind down the plastic shells to feed his machines. John Dolan remembered being told by Kove when he needed raw materials, that the materials were out there, he just had to go out and find them! Kove would give Dolan £50 or so in cash (a lot of money in those days) and he would have to track down the raw material. The acquisition of the first plastic injection-moulding machine in the UK marked a big step forward in Airfix’s fortunes. With it Airfix started manufacturing plastic combs and was very soon the market leader for combs. However, this market would not remain the exclusive preserve of Airfix forever, and so Kove used his new injection-moulding machines to make other ranges of goods. As one can see from the 1949 catalogue, toys would become a major part of the Airfix range.

Baby’s Bucket and Spade from 1951.

Selection of 1940s toys and products in cellulose acetate. JOHN DOLAN

Airfix toys of the 1940s.

Peter Allen as a young draughtsman, in 1963/4.

Before the war, most toys were made of wood or tin plate, but the development of plastics during the war enabled toys to be made out of the new material. Many of the very early toys were made out of cellulose acetate, which was used extensively during the war, although surviving products have warped badly over the years. Certainly many of the John Dolan toys I possess are now very ‘curly’ and it would be impossible to fit many of them together satisfactorily, if at all. Airfix would make its later toys and all the famous kits out of a much improved material. Shortly after the war, lots of cheap plastic toys were being imported from Hong Kong, and these were giving the plastic toy trade a bad name. The reason was that the Hong Kong companies tended to use a material known as ‘straight styrene’, which was a fairly cheap form of plastic. One of the big disadvantages of it was that if a toy was trodden on, it would shatter into lots of tiny pieces of plastic resembling shards of glass – not something that Britain’s premier plastic toy producer wanted to be associated with! So Airfix made its toys like Woofy the Sea Lion and the Ice Cream Tricycle out of a much improved, and more expensive, material known as ‘high impact polystyrene’ or HIPS for short. It took detail well and did not shatter. My Woofy and Ice Cream Tricycles are nearly seventy years old but they are still as good as new and have not warped, although like any septuagenarian they deserve careful handling. In the mid-1960s, Airfix racing cars were being made out of a stronger and more expensive plastic known as ABS plastic.

Toys were in many ways the ideal product to make out of plastic. Once a hardened steel mould had been made, literally thousands, if not millions of plastic replicas could be produced. Each individual toy was identical to the next and the plastic parts from the mould could be clipped, screwed or glued together. Bright colours could be used to avoid painting with potentially toxic paints. Any reject toys could be put through a grinder and the plastic used again. One can see this longevity in the famous Airfix kits. Some of the more popular kits would go on to have production lives of over fifty years, with several million kits being produced from one mould. Once a mould was paid for – and a Woolworth’s initial order would usually pay for the mould – Airfix could look forward to many profitable years from that mould. Peter Allen remembers that shortly after he joined Airfix, the mould for the Royal Sovereign classic sailing ship was finished and the ship kits were ready for shipment to Woolworth’s. He stated that the initial Woolworth’s order was sufficient to cover the cost of the mould. Any other production costs would easily be covered by the second batch of kits sent to the model shops. This gave Airfix a tremendous advantage over its rival companies.

Airfix also had an arrangement with several hundred of its smaller retail shops whereby each shop would make a standing order of £50 a month to Airfix and in return would receive £50 worth of new releases and other models from the range. This made it much easier for the small shops and also provided Airfix with a hefty sum of money each month. Apparently, when Matchbox introduced its new plastic kits, they were sold through wholesalers and this did not have any marked effect on Airfix because of their existing arrangement with their retailers. Where a product was likely to have only a short selling life, then it made sense to licence-produce a toy. The licence fee was a lot less than the mould cost so Airfix could make its money more quickly, and when interest in the toy dried up, Airfix did not have expensive moulds lying unused.

1940s tiles and toys. JOHN DOLAN

Zoobrix – a popular Airfix toy in the 1940s.

More 1940s Zoobrix. JOHN DOLAN

A boxed set of Zoobrix from the 1940s.

Zoobrix also came as rattles.

A selection of 1940s Zoobrix.

Violins from Airfix’s Musical Toys range.

More 1940s Zoobrix rattles.

One of Airfix’s most popular toys – the Ice Cream Tricycle, 1948.

Woofy the Sea Lion in 1948.

Eight Standing Figures and box from 1948.

Toys like the Weebles were already very popular, and, by taking out a licence, Airfix gained sole rights in the UK, which was good for the company. Being licensed to design and produce its own Weebles meant that Airfix avoided import duties and could make more money once their moulds were paid for. Licences for toys derived from film or TV programmes could be very lucrative, but the toy company had to be ready for the release of the programme or else the toy might miss the boat. One ‘boat’ that was definitely missed was the Nautilus kit produced in the late 1970s. Peter Allen said he couldn’t understand why it was ever started. It was based on the Nautilus used in the 1950s Disney film version of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. In late 1976 the Disney film was released on television, and it may be this decision that led Airfix to decide a model of the Nautilus would sell well. However, the kit was not ready in time and so its only hope of decent sales was gone. It was finally announced in the 1981 catalogue. The mould was actually completed by Palitoy but Peter persuaded the new owners to sink it! Some test shots still exist and one was used by Comet Miniatures to make a resin version. With any TV or film licensed product, you need to gamble on the show being a success and that you are ready for it. Interestingly, the 1960s Tarzan and High Chaparral figure sets, which were based on two very popular TV series, would later be sold by HaT as ‘Jungle Adventure’ and Humbrol as ‘Cowboys’, their original name, which neatly got round licensing issues.

The earliest known licence deal was the David Hand Animaland range. Licensed toys seem to have a greater value to collectors because they tend to be available for a shorter time and in limited quantities. When it came to the construction kits, Peter Allen said that Airfix would not entertain an airline, for example, sponsoring a kit because it would give the sponsor some kind of a hold over future releases of the kit. Airfix would sometimes allow the airline to contribute to the cost of producing their decals as that did not give them a veto over future decal choices.

By 1949 Airfix had been moulding lots of toys and household goods and the more popular ones would appear in the 1949 catalogues I now possess. Below is the list from the 1949 retail catalogue, under the headings in the catalogue, but rearranged slightly to be in numerical order. I also have copy of a 1947 catalogue, courtesy of Paul Morehead of Plastic Warrior. Any items from that catalogue that do not appear in the 1949 ones have been added and are shown in italics. Also a few toys that were known to be available at that time but which do not appear in the catalogue are entered as ‘not listed’.

Speciality Toys

409B/L

6-Piece Dining Room Set

–

5-Piece Living Room Set (not listed)

–

?-Piece Bedroom Set (not listed)

414B/L

Plastic Pistol

417

Toy Telephone (and Money Box)

417K

Night Light Telephone (variant of above)

420

3in Articulated Doll (flesh or black)

425

Ice Cream Tricycle

461

Ginger Nutt, Esq. (see Animaland)

480

Ferguson Tractor

482

‘Woofy’ the Performing Sea Lion

483

Atom Ray Gun

484

Water Pistol

486

Dolly’s Spectacles or Sunglasses

551

Kennel of Dogs (4 types of dog): Setter, Spaniel, Greyhound and Alsatian

551L

Dogs (six types ideal for doll’s houses)

Musical Toys

426

Ukelele (2-coloured)

427

Toy Violin (horsehair bow)

450

Concertina (2-coloured)

451

Airmaster Mouth Organ

Brix Toys

429

Jack-in-the-Box

430

Zoobrix (loose)

430B

Zoobrix (boxed sets of 6)

431B/L

Playbrix

432B/L

Zoo Rattles (teething ring, handle)

432LC

Zoo Rattles (silk cord, no handle)

435

Buildy-Brix (build, rattle and float)

435B

Buildy-Brix (16 in a box)

Floating Toys

411

Baby Ducks

416

Mother Ducks (3 colours)

419

Junior Ducks (3 colours)

Animaland Series

437

J. Arthur Rank, David Hand Animaland Playbrix (6 colours)

438L

Animaland Zoo Brix (12 unpainted characters)

438LP

Animaland Zoo Brix (painted)

438B/P

Animaland Zoo Brix (unpainted/painted)

460L/P

Animaland Characters (12, unpainted/painted)

461

Ginger Nutt, Esq. (5in high)

Cowgirl and Indian from 1948.

Mounted British policemen from 1948.

Royal Canadian Mounted Police from 1948.

A selection of mounted figures from Airfix’s 1948 range.

Mounted rider from 1948.

The famous Ferguson Tractor model, 1949.

David Dodd Hand (1900–1986) was an animator who worked on several Disney films such as Snow White and Bambi. He left Disney in 1944 and Joined J. Arthur Rank in the UK in 1946, where he established Gaumont British Animation. There he produced the Animaland and Musical Paintbox cartoon series. Much of the Animaland series revolved around a character called Ginger Nutt, Esq. and Airfix presumably took out a licence to model toys based on these cartoons. Unable to get distribution for the cartoons in the USA, Gaumont British Animation ceased in 1950, and so it is likely that the Airfix range ceased shortly after.

Soldiers, Mounted Police, Huntsmen and Other Figures

415

Mounted Horse and Life Guards (painted)

415

Various combinations, painted or unpainted

500

Motorbikes and Riders (2 types)

500M

Motorbike only

501/2

Riders only (2 types)

504P

Set of 8 Standing Soldiers (painted)

504U

Set of 8 Standing Soldiers (unpainted): 505 Commando, 506 Paratrooper, 507 RAF Pilot, 508 Able Seaman, 509 German Soldier, 510 Japanese Soldier, 511 Knight (14th-century) and 512 Private of the Line (c. 1750)

520P/U

British Mounted Police (painted, unpainted)

520BPP

British Police (riders only, painted)

521P/U

RCMP (painted, unpainted)

521CPP

RCMP (riders only, painted)

531

Mounted Huntsmen (assorted, hand-painted)

532

Hunting Set (2 Masters, 2 Followers, 4 Horses and 2 Foxhounds)

533

Master of Hounds (riders only)

534

Followers (riders only)

Toys on Cards

410C

Scissors

412C

Doll’s Fish-Eating Set (3 pieces)

413C

Doll’s Knife, Fork and Spoon Set 418C Zoo Animals (6 to a card, 18 types)

421C

Road Signs (6 signs to be painted)

422C

Greyhounds (6 models in different colours)

423C

Racehorses (6 models in different colours)

428

Doll’s Lipsticks

Baby Goods

201

Teething Rings (small)

202

Teething Rings (corded)

203

Teething Bites (corded)

258

Soothers, Aseptic Shield

408J

Baby Serviette Rings

408

Animals on Wheels, Serviette Rings: 401 Rabbit, 402 Elephant, 403 Dog, 405 Chicken, 406 Duck, 407 Camel

Combs

711

Pocket Comb, 5in long, Fine Teeth

712

Pocket Comb, 5.5in long, Fine and Wide Teeth

721

Tail Comb, 7.75in long

725

Men’s 7in Comb, Fine and Wide Teeth

751S

6.5in Dressing Comb, Fine and Wide Teeth

752

6.5in Dressing Comb, Fine and Wide Teeth

754

7in Dressing Comb, Fine and Wide Teeth

760

7.5in Dressing Comb, Fine and Wide Teeth

761

7.5in Dressing Comb

770

Fine-Tooth Comb, 315/16in long

777

Side Comb, 3.5in, Straight and Wavy Teeth

In the late 1940s and very early 1950s, Airfix was the largest manufacturer of plastic combs in the UK and vast numbers were sold through Woolworth’s stores. Being injection-moulded, they were a revelation to the tonsorially adorned public who were used to the saw-cut acetate combs of an earlier period. I have a poor photocopy of an old comb catalogue (not very exciting reading), which shows that Airfix had all the main types covered, and comb design has hardly changed in the seventy-odd years since Airfix was churning them out. Airfix finally withdrew from comb making in the early 1950s after several other companies started manufacturing them and the profitability for Airfix consequently suffered. Fortunately, Airfix put its resources into its new plastic construction kits, where, despite growing involvement from many other companies, it would become and remain the market leader. Peter Allen said that the Airfix designers once came across a box of combs that had been hidden in a corner of the Haldane Place factory for many years. They were passed around the design team, who ran their fingers down the teeth and found that lots of the teeth flew off! No doubt the combs were suffering from old age, but this is a problem that still affects many cheap combs today.

It looks like the comb range may have been shrinking by 1949. There is an interesting footnote to the story of the combs. In 1959/60, Windsor’s took back the original moulding machine and placed it in their museum, supplying Airfix with a replacement brand-new machine. So presumably that original machine, which was eventually to spawn the largest and most famous range of construction kits in the world, is still in existence and proudly displayed by its manufacturers – a fitting tribute to Airfix.

Accessories for Games and Toys

301

Counters for Games (4–6 colours)

302

As above, 25.4mm diameter × 2mm thick

305

As above, 31.75mm diameter × 2mm thick

333

Interlocking Counters for Games (Poker Chips)

334

Interlocking Counters for Games (Poker Chips)

444

Wheels for Toys, 23/32in diameter

445

Wheels for Toys, 7/8in diameter

446

Wheels for Toys, 1.25in diameter

447

Wheels for Toys, 1.5in diameter

448

Wheels for Toys, 2in diameter

449

Wheels for Toys, 3in Diameter

Fancy, Household and Stationery Goods

610

Plastic Boxes, 4in × 3in × 1.5in, Hinged

611

Plastic Boxes, 4.75in × 3in × 1.5in, Food Use

778

Hair Curlers, Washable, Bright Colours

800

Plastic Clothes Pegs, Vivid Colours

801

Finger Plates

810

Scone Cutters

901

Rulers, Coloured and Flexible

910

Pencil Boxes, 3-Tier

All in all, Airfix had quite a large range, although not all are toys. The famous combs are still there and remind us that Airfix was the pioneer in plastic injection-moulded products in Britain. Also there is a small range of household goods and some baby goods. The baby goods would be replaced in the 1970s by the Romper Room and similar ranges. The small range of household goods would also be replaced by much more professional ranges, such as Crayonne (Habitat), produced by the Industrial Division (seeChapter 12).

So successful were the combs that soon Airfix bought the shop in the Hampstead Road where they were working from and acquired another nearby.

The Ferguson Tractor, pattern no. 480, is arguably the most famous and important toy produced by Airfix. It is often mistakenly described as the first Airfix kit, but it was designed before the kits were started and was not sold as a ‘kit’ until the mid 1950s. Airfix had been approached by Harry Ferguson, who had recently launched his highly successful TE20 tractor onto the market place. As the leading plastic injection-moulding company in Britain, Airfix was tasked with producing a 1:20 scale model of the tractor that could be used by salesmen to sell the tractor and also give to customers. It was sold as an assembled model that could be disassembled and put back together, so technically it was not a kit. Airfix later received Harry Ferguson’s blessing to sell the model to the general market, which it did in the early 1950s.

When the first true Airfix kit, the Golden Hind, was sold through Woolworth’s around 1953, it was supplied in a new plastic bag with a coloured header with instructions stapled to the bag. By 1955, the Ferguson tractor was being sold in a similar packaging, in which it continued until 1959, when it was finally withdrawn, along with the Southern Cross and the original Spitfire, BT-K.

John Dolan, however, claimed in his interview that he approached Harry Ferguson. He said that he told Kove that Airfix could not make combs forever and needed to branch out, whereupon Kove exploded. When he calmed down he asked Dolan what he proposed. Dolan said toys and fancy goods, to which Kove replied, ‘We will never make toys. You are ridiculous. You do not know what you are talking about.’ This does have the ring of truth about it, as when Ehrmann and Gray asked Kove to produce aircraft kits, he was against it, being happy with sticking to sailing ships. So Dolan replied, ‘All right, but there is an enormous shortage of toys, and when Aberdeen Combs get going and Halex really get going you will be torn to shreds in the comb market.’ So Airfix started making toys.

Kove travelled to the USA to see what they were doing in toys, and when he returned Airfix he started making toy ducks, scissors and all sorts of things. Dolan never liked the rulers because the early plastic shrank and expanded. They were originally made in cellulose acetate but Airfix was starting to use styrene as well. He also carefully studied the market for toys so he could assess what was going to be the next ‘big thing’. He then thought that if you could get into the new National Health Service and make supplies for them, you were in! The first article he designed was a medicine pourer, but Airfix never produced it.