Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

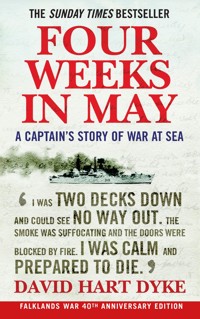

Reissued for the 40th anniversary of the Falklands War. A Sunday Times Bestseller 'Electric... Outstanding.' Guardian In March 1982 the guided-missile destroyer HMS Coventry was one of a small squadron of ships on exercise off Gibraltar. By the end of April that year she was sailing south in the vanguard of the Task Force towards the front line of the Falklands War. On 25 May, Coventry was attacked by two Argentine Skyhawks, and hit by three bombs. The explosions tore out most of her port side and killed nineteen of the crew, leaving many others injured. Within twenty minutes she had capsized. In her final moments, after all the survivors had been evacuated, her Captain, David Hart Dyke, himself badly burned, climbed down her starboard side and into a life-raft. This is his compelling and moving story.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 417

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

FOUR WEEKS IN MAY

David Hart Dyke began his naval career in 1958 as one of the last intake of National Servicemen, before entering Dartmouth as a regular officer. After service in ships around the world, he has been appointed to several senior posts, among them a member of the Directing Staff at the Naval Staff College, Greenwich; Commander of the Royal Yacht Britannia; Naval Attaché and Chief of Staff to the Commander British Naval Staff in Washington, USA; Director of Naval Recruiting at the Ministry of Defence, and Captain of HMS Coventry during the Falklands War.

David Hart Dyke was appointed a Lieutenant of the Royal Victorian Order in 1979 and awarded a CBE in 1990, the same year that he retired from the Royal Navy. Soon after, he was appointed Clerk and Chief Executive of the Skinners’ Company, one of the Great Twelve City Livery Companies. He finally retired in 2003 and lives in Hambledon, Hampshire, where he pursues his main interest of painting in watercolours. He is married to Diana (D) and they have two daughters.

‘The devastating story of HMS Coventry, the last warship sunk in the battle for the Falklands – by its captain.’ Daily Mail

‘Four Weeks in May is a refreshingly different war memoir… [Hart Dyke] explains the complex ties binding commander and crew; explores the emotional effects of warfare on the men in the mess deck and the wardrooms, and reveals the different ways in which people react in situations of extreme danger.’ Yorkshire Evening Post

‘Even those with little interest in military history or no recollection of those days 25 years ago cannot fail to be moved.’ Hampstead and Highgate Express

‘Outstanding… David Hart Dyke gives you the “business end” of that conflict, the story of the sailors in harm’s way. It is one of the most moving, honest and vivid portraits of life – and war – at sea you will ever pick up.’ Navy News

‘A riveting story you won’t want to miss.’ Coventry Evening Telegraph

‘Four Weeks in May is a page-turner… elegantly and tightly written… The tension between his determination to uphold morale, the upbeat letters home, private moments of honest reflection, the self-depreciating humour and what every reader knows will be the disastrous outcome of those four weeks, is compelling.’ Naval Review

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by Atlantic Books,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This e-book edition published in Great Britainby Atlantic Books in 2021.

Copyright © David Hart Dyke 2007

The moral right of David Hart Dyke to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-83895-474-1

Maps and graphics © Mark Rolfe Technical Art

Images of Firth of Forth and Turning South for the Falklands © Crown Copyright/MOD. Reproduced with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Extract from One Hundred Days by Alexander Woodward reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd © Alexander Woodward with Patrick Robinson 1992.

Extract from Memories of the Falklands by Iain Dale (ed)reproduced by permission of the author © Margaret Thatcher 2002.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZwww.atlantic-books.co.uk

For the Ship’s Company of HMS Coventry 1982and, of course, D

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

List of Maps and Diagrams

Acknowledgements

Preface

HMS Coventry Battle Honours

Prologue: Apocalypse

1 Before the Storm

2 Preparing for War

3 Testing Times

4 On the Brink

5 At War

6 Changing Fortunes

7 Under Pressure

8 Touch and Go

9 Last Stand

10 Rescue

11 Day’s End

12 Brave Deeds

13 Heading Home

14 Coming to Terms

15 Full Circle

HMS Coventry Roll of Honour

HMS Coventry Honours and Awards 1982

Ship’s Company 1982

Epilogue

Diagrams

Bibliography

Index

ILLUSTRATIONS

SECTION 1

PAGE 1Coventry under the Forth Bridge

Coventry turning south for the Falklands

PAGE 2 The author as a midshipman

Diana, the author’s wife

PAGE 3 The Coventry postmark

A letter from the author to his children

PAGE 4 The author being winched from Coventry by helicopter

Sea Harriers and Harrier GR3s on the deck of Hermes

SECTION 2

PAGE 1 View of Coventry from Broadsword

Two Argentinian Skyhawks on the attack

PAGE 2Coventry as the first bomb strikes

Coventry slowing to a stop

PAGE 3Coventry listing to port and beginning to settle in the water

PAGE 4 View of Coventry from a life-raft A helicopter searching for survivors The last view of Coventry

SECTION 3

PAGE 1Britannia greeting QE2 on her return to Southampton

The author and family outside Coventry Cathedral

PAGE 2 Presentation of the new sword

Dinner at 10 Downing Street

PAGE 3 Keel-laying

The author handing over the Cross of Nails

PAGE 4 Ex-Coventry men by the ship’s memorial on Pebble Island

The inscription on the ship’s memorial on Pebble Island

MAPS AND DIAGRAMS

The Atlantic Ocean

Argentinian Air and Naval Bases

Disposition of Forces before Exocet Attack, 4 May

Ship Losses, May 1982

The Falkland Islands

Task Force Command and Control

HMS Coventry (D118)

Bomb Damage

Operations Room

TASK FORCE COMMAND AND CONTROL

LONDON

The Prime Minister

Rt Hon Margaret Thatcher MP

The Secretary of State for Defence

Rt Hon John Nott MP

Chief of the Defence Staff

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Terence Lewin

Chief of Naval Staff and First Sea Lord

Admiral Sir Henry Leach

Chief of the General Staff

General Sir Edwin Bramall

Chief of the Air Staff

Air Chief Marshal Sir Michael Beetham

NORTHWOOD

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book became a serious project after author Patrick Robinson and Dr Campbell McMurray, the Director of the Royal Naval Museum, Portsmouth, had seen an early draft and considered it worthy of publication. I am grateful to them for their encouragement, since, without it, these pages would have just gathered dust at home.

I wish to thank my daughters: Miranda for providing the necessary spur to start me writing by making a transcript of the tapes I made on which the book is based, and Alice for her suggestions and scrutiny of the manuscript. Thanks are also due to Sir Michael Jenkins, Vice-Admiral Sir John Webster, Captain Michael Barrow, Major-General Julian Thompson and Admiral Sir Sandy Woodward for their advice and comment.

I am indebted to Toby Mundy, Angus MacKinnon and Emma Grove of Atlantic Books for their unfailing support and enthusiasm; Angus deserves particular thanks for his meticulous and skilful editing.

Finally, I thank my agent, James Gill, who guided me so professionally all the way to publication. Nothing would have happened without him.

My wife D deserves special praise for both her important contribution to the book and for living through the dramatic events of 1982 with remarkable calm and strength.

PREFACE

In March 1982, a group of Argentinians raised their flag in South Georgia and started a dramatic chain of events. On 2 April, Argentinian troops invaded the Falkland Islands and later South Georgia. The small British garrison of Royal Marines was overwhelmed by the vastly superior number of invaders.

By 5 April, the main components of a British Carrier Battle Group had set sail for the South Atlantic. A few days earlier, a flotilla of ships exercising off Gibraltar under the command of Rear Admiral Sandy Woodward had been ordered to sail south in advance of the main force. HMS Coventry was part of this advance group. Diplomatic efforts, supported by a United Nations resolution, failed to persuade Argentina to remove its occupying troops.

South Georgia was reoccupied after a brief encounter with the Argentinian garrison on 25 April. A number of fierce engagements followed in the war zone surrounding the Falkland Islands. On 21 May, some 5,000 British troops stormed ashore at San Carlos Bay and established a bridgehead, from where they advanced to Darwin and Goose Green. A further thrust took place at Bluff Cove and the advance towards Port Stanley, the capital, began in earnest.

Almost all the high ground around Stanley was in British hands by 12 June and the routed Argentinians fell back into Stanley. On 14 June, their commander surrendered his forces and the commander of the British land forces reported: ‘The Falkland Islands are once more under the Government desired by their inhabitants. God Save the Queen.’

Four Weeks in May is the story of the guided-missile destroyer Coventry, which made a significant contribution to this remarkable victory, achieved against very considerable odds 8,000 miles from home, and which in the end went down fighting against bomber aircraft. It is also the story of the ship’s company, who fought a dangerous, arduous and intense battle in one of the most inhospitable regions of the world with great courage and endurance. And lastly, it is my own story as Coventry’s captain. It was my privilege to lead such brave men in battle and they are, quite simply, my heroes.

Many people who have suffered in war do not care to talk about their experiences because, when they do, they relive them intensely – as if these events had happened only yesterday, not years or decades earlier. Some go to their graves without ever feeling able to describe or discuss what they went through, even with close friends or family. I was lucky: over time, I learnt to shut out the more painful memories and to live more easily with them. And I wanted to tell Coventry’s story before I got too old, even if my descendants would only read it after stumbling across these pages in the attic.

My account is largely based on tapes which I made soon after I returned from the South Atlantic. Even now, I can hear myself speaking into the microphone in a distinctly flat voice as I began to recover at home from the traumas of the war: I simply wanted to set down a record of events and my impressions of them while both remained fresh in my memory. I have never wished to listen to those tapes since, but I have had them transcribed. I have also made use of the letters my wife and I exchanged during the conflict. In addition, I have drawn on articles I wrote in the autumn of 1982 for various naval publications recounting my experiences, contemporary newspaper accounts of the conflict that I kept, and the reminiscences of some of my former crew members. These reminiscences, which come from diaries kept at the time or accounts written later, were offered to me when I made it known that I was writing this book and seeking contributions.

I hardly comment on the broader strategy of the campaign and the tactics employed: where I do, it is only as they affected me as one of the commanding officers of the ships operating in the front line. I do not wish otherwise to pronounce on the conduct of the war. This is not a history book: it is the story of the war at sea as I saw it in Coventry and as I recorded it back in 1982.

I write about one warship and its men, but there were over forty others in the campaign whose daring exploits would make compelling reading. I have an undying admiration for those ships and their crews, especially the ones Coventry was fortunate to work with closely, and I hope that Four Weeks in May goes some way towards showing how magnificently they performed in this most testing of wars. Their hardships and their fears were at least as great as mine, and they faced them with the utmost resolve.

I have mentioned some of my former crew members by name but there are many others whom I remember well and would have included had space allowed. I only hope that this book pays sufficient tribute to everyone on board, for I do not know of a single person in the ship who did not excel in his duties and live up to the fighting tradition of the Royal Navy. It is, after all, not ships, aircraft and weapons that win wars, but people. And this story is all about people.

Hambledon, 2006

HMS COVENTRY BATTLE HONOURS

Quiberon 1759Trincomalee 1782Spartivento 1940Atlantic 1940Norway 1940

Greece 1941Crete 1941Libya 1941Mediterranean 1941Falkland Islands 1982

The name of Coventry is an illustrious one in Royal Navy history going back to the seventeenth century. The battle honours show HMS Coventry’s long and active history, and in more recent times there has been a proud association between the city and the ship.

The fourth HMS Coventry was completed in 1918 and later converted into an anti-aircraft cruiser with high-angle 4-inch guns. In 1941 she joined the desperate fighting in the Mediterranean and shot down more enemy aircraft than most other ships. In September 1942 she was bombed and sunk off Tobruk.

The fifth HMS Coventry, an anti-aircraft destroyer, entered service in 1979 and, much like her predecessor, distinguished herself by destroying more aircraft than others, either with her own missiles or by radar control, during the Falklands War. On

25 May she came under heavy attack and was struck by three bombs. In seconds she was on fire, flooding and listing rapidly. She was abandoned with the loss of nineteen men – but not before several of her crew had crawled in darkness and toxic fumes to check for anyone alive. They brought many to safety.

FOUR WEEKS IN MAY

PROLOGUE

APOCALYPSE

During the last few hectic days of the conflict, we all realized that the odds of emerging unscathed were stacked against us. We always knew that we might be hit from the air – it was just a question of where and of how many casualties we would sustain. After all, three warships had already been sunk and others damaged. I frequently thought along these lines and I am sure most of my sailors did, but we never admitted it openly. That would have been demoralizing. Conversations were brave and cheerful, full of confidence that we would all get home safely. We were all strengthened by such talk and by the bold banter and good humour among colleagues, however much we inwardly believed that some of us might never get back.

I was shocked when, a day or two before the end, the first lieutenant, the second-in-command, came into my cabin and with noticeable hesitation said, ‘You know, sir, some of us are not going to get back to Portsmouth.’ Although it disturbed me to hear him say this, I thought it was very brave of him to admit to his captain what he really felt, and at least we no longer had to pretend to each other about the risks we were running. He included himself among those who would not return and in his last letter home he told his wife as much. She was to receive the letter just after she heard the news that he had been killed.

Towards the end of our time, the strains were definitely beginning to tell. Although most people remained outwardly strong and in control of themselves, feelings clearly ran high. Once, quite unprompted, a young sailor on the bridge showed me photographs of his girlfriend and talked freely about her. He was in need of reassurance and this was his way of showing it. There had already been air raids that day, and we knew the enemy would be among us again very soon. On a similar occasion, a petty officer produced a prayer, given to him by his mother when he first joined the Navy, which he kept with him all the time and which clearly meant a great deal to him, especially now. He asked me to read it in our church service on Sunday and then moved quickly out on to the wings of the bridge for fear of showing the tears in his eyes. War can be an emotional business.

I found it depressing to wake each morning to beautiful, clear and sunny weather which favoured the enemy air force and illuminated us sharply against the blue sea. I would wait on the bridge, heavily clothed for protection against fire, lifejacket and survival suit around my waist, ready for the next air raid warning. When it came, I would go down to the operations room to prepare to counter the threat. These moments invariably demanded a certain amount of nerve: you had to put on a confident face as men watched you go below and wondered whether we would win the next round and survive unharmed.

Tuesday, 25 May 1982, was another of those days. We had survived two air raids and shot down three aircraft with missiles. Inevitably, there was another warning and I went below feeling more fearful than before. I paused for a moment at the top of the hatch and talked briefly to Lieutenant Rod Heath, the officer responsible for the missile system. I never saw him again. At 6 p.m. precisely, I pressed the action-station alarm from the command position in the operations room and within four minutes the ship was closed down, ready and braced for action.

As we listened to the air battle raging, we tried desperately to avoid losing radar contact with the fast and low-flying enemy aircraft and to predict where they were going next. Once again, it was a question of split-second timing, and I had to decide whether to guide our Sea Harrier fighter aircraft to intercept or to bring the ship’s missile system to bear. There was the familiar air of quiet professionalism, the sound of keyboards as operators tracked targets and of soft but urgent voices exchanging information over the internal lines. It was like some frantic computer game, and we knew we would lose the battle if we could not keep up with its ever-quickening pace. As I glanced around at the warfare team, their pale and anxious faces said everything. I looked at the clock – it was nearly 6.15 p.m. – and prayed that time would somehow accelerate, enabling us to see out what would be the last air raid of the day. Even now, I knew that outside in the South Atlantic the light was already beginning to fade, the prelude to another brilliant sunset.

As it was, we came up against a very brave and determined attack by four Argentinian aircraft. We opened fire with everything we had, from Sea Dart missiles to machine guns and even rifles, but two aircraft got through, hitting us with three 1,000-pound bombs, two of which exploded deep down inside the ship. The severe damage caused immediate flooding and fire, and all power and communications were lost. Within about twenty minutes, the ship was upside down, her keel horizontal a few feet above the sea. Tragically, nineteen men were killed, most by the blast of the bombs. Yet it still strikes me as remarkable that some 280 of us got out of the ship, whose interior was devastated and filled with thick, suffocating smoke. I can only put that down to good training, discipline and high morale. You need all of these, especially the last, in desperate situations.

My own world simply stopped. I was aware of a flash, of heat and the crackling of the radar set as it literally disintegrated in front of my face. When I came to my senses, I could see nothing through the dense black smoke, only people on fire, but I could sense that the compartment had been totally devastated. Those who were able to take charge did so calmly and effectively. It seemed like an age, but when you are fighting for your life, the brain speeds up and time slows down: the focus of your thoughts narrows and you concentrate on just one thing – survival. At such times, pain, injury and even freezing seas are not even distractions; they simply do not enter into your calculations.

I was two decks down and had a long way to go to reach fresh air. I could see no way out and was suffocating in the smoke. The ladders were gone and doors were blocked by fire. I was calm and not at all frightened. I was feeling quite rational and was prepared to die. There seemed to be no alternative.

CHAPTER 1

BEFORE THE STORM

I was fortunate to be married to someone who had a naval background and therefore understood the life of a sea-going naval officer and the necessary separations involved. Although my wife’s father was a diplomat, one who had served abroad for most of his life, her great-grandfather, great-uncle, both grandfathers and an uncle were all admirals. One of her grandfathers, John Luce, was the captain of the light cruiser Glasgow in the Battle of the Falklands in 1914. A lucky ship, Glasgow had survived the earlier defeat of a British squadron by the Germans off the Chilean coast at Coronel.

I first encountered Diana – known by family and friends as just D – while serving in the frigate Gurkha in the Persian Gulf in 1966. Her father, Sir William Luce, was the Political Resident in Bahrain with responsibilities for the Gulf, and just before he retired we took him to sea to call on all the region’s rulers and sheikhs, beginning with Kuwait and ending in Oman in the port of Muscat. Sir William had been granted permission to take his daughter and his social secretary, Vicky Vigors, on the three-day trip, although he had been advised not to inform the First Sea Lord, who happened to be his brother, Admiral Sir David Luce.

The two girls slept in the first lieutenant’s cabin with a Royal Marine on guard outside throughout the night, and they spent a great deal of time during the day sunbathing in bikinis on the teak deck just below and in front of the bridge. There was no shortage of volunteers to keep watch on the bridge and it was noticeable that their binoculars were not exactly fixed on the far horizon looking for ships. My own efforts at pretending not to approve of women at sea did not last long as one day D asked me if I could show her where we were on the chart. I was Gurkha’s navigator, but replied that I had absolutely no idea, throwing the rubber on to the chart and adding that we were probably just about where it landed. This rather relaxed and nonchalant approach to navigation clearly did the trick, however, as we were married eighteen months later.

My naval connections could not compare with D’s. My father was a naval officer who joined at the age of thirteen in the early 1920s and served throughout the Second World War, mainly in the Atlantic. He retired shortly after the war, went into the Church and became parish priest of the village of Cowden in Kent. He died in 1971 while on a working holiday on the West Indian island of Nevis: he had been running the church there to allow the incumbent to return home to England for a short break.

In 1976, when I was the commander of the destroyer Hampshire, we passed Nevis on our way to Trinidad but did not have time to stop. I was none the less able to fly to the island in the ship’s helicopter to pay a very brief visit to my father’s grave. I descended from the helicopter in my white uniform and began to walk the short distance to the church. As I did so, I quickly found myself being followed by a large number of excited local people. They continued to follow me with great curiosity wherever I went – to the church, the grave and to the rectory where my father stayed. I was puzzled at first, but it transpired that the members of this small, church-going community thought I actually was my father, now resurrected and descending from the heavens to visit them once again. The confusion was perhaps understandable: I resemble my father, and my white uniform could well have been taken for the white cassock that he habitually wore in Nevis. Eventually, I was bid a sad farewell, as if I were him, from hundreds of well-wishers while I waved goodbye from the helicopter before it lifted off and returned to the heavens. It was an emotional visit.

There have been only two other naval Hart Dykes as far as I am aware. Henry was a midshipman who in the 1850s served in Agamemnon, the first ship of the line to be powered by both sail and steam, and he retired as a rear admiral, while Wyndham ended his career with the rank of commander after serving in both world wars. My Hart Dyke grandfather served in the Indian Army, winning a DSO in the First World War, and my father’s elder brother also had a distinguished career in the Army, winning a DSO in the Second.

Among my mother’s family, the Alexanders, were some very good artists, my mother being one and her uncle Herbert another. Two of her other Alexander uncles, Boyd of the Rifle Brigade and Claud of the Scots Guards, became famous explorers and naturalists whose exploits in Africa in the early twentieth century are recorded in the two volumes of From the Niger to the Nile, written by Boyd in 1907. Boyd had a twin brother, Robert, my mother’s father. In 1910 Herbert was asked by Captain Scott to go on his expedition to the South Pole as the artist but his father would not let him go as he did not want to risk losing another son. In 1904 Claud had succumbed to blackwater fever in Africa and Boyd was killed six years later by tribesmen near Lake Chad in northern Nigeria, an area he largely discovered and mapped. Edward Wilson went with Scott to the Pole instead. The Alexander genes gave me both an interest in painting – in my case watercolours – and also a twin brother, Robert.

As a naval officer’s son, during my formative years I thought only of the Navy as a career, though near the end of my schooldays I was diverted towards university. It was not possible at that time to join the Navy as a seaman officer after university; the service wanted to educate its officer recruits straight from school in its own way – broadly, in the ways of the sea and following a more technical curriculum. A degree course in an arts subject was probably considered more of an obstacle than an attribute when it came to moulding people into naval officers at Dartmouth. After missing the chance to join the Navy from school, I then declined to go to university and waited for the call to do national service. I saw an opportunity of gaining a commission in the Navy during my national service and then, or so I hoped, becoming a regular officer. National service itself was almost at an end, and it was a risky plan. But it worked, and I arrived at Dartmouth about two years older than my contemporaries and after I had spent a year at sea as a midshipman.

After Dartmouth, I spent many years at sea, mostly in destroyers and frigates, projecting the United Kingdom’s interests around the world and helping to make it a more stable place. I passionately believed in this important role, one in which, after centuries of experience, the Royal Navy was highly effective. I specialized in navigation, an area which embraced warfare in all its forms and the conduct of operations. By the nature of the job, I was always close to the commanding officer: I was responsible for the safe navigation of the ship and also ran the operations room when we were practising for war. I was therefore well trained for command when the time came. In addition, I had held two teaching posts, one at Dartmouth and the other at the Naval Staff College in Greenwich. Following my time at the Staff College, I was fortunate to be appointed the commander of the royal yacht Britannia for two years and so witnessed at first hand the impact the vessel made with the Queen embarked as it visited various heads of state abroad, earning much goodwill and valuable trade agreements for the UK.

I was given command of the modern guided-missile destroyer Coventry in 1981 after twenty-two years of very enjoyable and rewarding appointments. We were to be busy at sea from the day I joined, and I soon found that I had inherited a well-run and efficient ship – something which had not always been my experience. Coventry spent time with the Standing Naval Force Atlantic, a squadron of NATO ships, and took part in a major exercise in the North Sea. Then, in the spring of 1982, she was to depart on what proved to be her final voyage.

We sailed from Portsmouth in the middle of March in company with Antrim, flagship of the Flag Officer of the First Flotilla, Rear Admiral J. F. ‘Sandy’ Woodward, to meet up with other ships departing from Plymouth. We then set course as a group for Gibraltar, which was to be our base as we carried out a number of routine weapons-training exercises, including missile firings. We would take advantage of the various training facilities ashore and the practice targets at sea, provided by both submarines and aircraft, to practise our war-fighting skills. There would also be sporting and social activities for ships’ companies – opportunities for all to catch up with friends and to compare notes with other ships. It all seemed perfectly straightforward: a standard period of springtime exercises for ships based in home waters.

In Gibraltar, Coventry was berthed alongside Glasgow, our friendly sister ship. Paul Hoddinot, the captain, came on board for a drink and a chat with me, and there were similar comings and goings between friends at other levels in both ships. Paul was a near contemporary of mine but his background was in submarines and so I did not know him all that well. He seemed quietly confident, impressive and very likeable. I thought it would be fun to be working with him and his ship, which was clearly a good one.

I learnt later that some of his sailors had taken the tompion off Coventry’s 4.5-inch gun as a prank and had taken it back on board Glasgow as a trophy. This stainless steel cylinder carries the ship’s crest on one end and slides over the gun to help make everything look smart when entering and leaving harbour; it also prevents rain, sea and spray from getting inside the barrel. No doubt it would have been given back when the ships met up again. As it was, I had no idea the tompion was even missing until after the war, when Paul came to see me at home in Hampshire and presented me with it. Thus it survived and is now a valued memento which acts as a rather original doorstop.

Another of our sister ships, Sheffield, with Captain Sam Salt in command, glided gracefully into harbour looking very smart and purposeful. I went on board to see Sam and hear all his news. He was a friend from several years before when our paths had crossed during various training courses in Portsmouth, and he was always good fun and a thorough professional. Everyone loved working for Sam and he ran a very happy and efficient ship.

The three Type 42 destroyers (Coventry, Glasgow and Sheffield) together at this time were, like all of the Royal Navy’s destroyers and frigates, designed to meet a number of Cold War contingencies. Our main role was to counter the threat posed by Soviet aircraft heading south over the North Atlantic with the ships’ long-range missile system, Sea Dart. This we rehearsed both at sea and ashore in simulators, and Sea Dart performed best when intercepting aircraft flying high and with the missile’s detection and guidance radar looking over the sea, unhindered by any land mass. Coventry was practised in operating in the wild seas of the Atlantic or in the North Sea with both air support and early warning of any threat from the air. Early warning was usually provided by either shore-based maritime patrol aircraft such as Nimrod or the Navy’s own carrier-borne aircraft.

Coventry, like her sister ships, was equipped for anti-submarine warfare as well: she carried a Lynx helicopter which could be fitted with homing torpedoes capable of attacking submerged submarines at some distance. Additionally, the ship had torpedo tubes fitted on deck to counter any closer submarine threats. The Lynx was also capable of firing the new Sea Skua missile designed to attack surface targets, though this had yet to be fully evaluated and we had not had the opportunity to practise with it. Coventry’s fully automated 4.5-inch gun could be used against air and surface targets up to medium ranges, and for shore bombardment.

In short, we had a bit of everything to throw at an enemy but we would always be at our best with support from other units to provide early warning of any threat, whether from the air, the surface or under the surface. All ships were equipped with electronic listening devices for detecting enemy radar and communication emissions; such intelligence gathering was vital if we were to have advanced warning of enemy activity. If there was an Achilles heel in Coventry’s armoury, it was the lack of effective close-in weapons providing a last layer of defence, particularly against air attack. We only had two single 20-mm Oerlikon guns of Second World War vintage, one each side of the bridge.

Coventry was the fifth Royal Navy ship of that name. She had been launched in 1978 by Lady Lewin, the wife of the then First Sea Lord, who always kept in touch with the ship and had come on board for a visit not long before we sailed for Gibraltar. Unfortunately, none of Coventry’s predecessors had survived the wars in which they fought. Her immediate predecessor, a light anti-aircraft cruiser, had distinguished herself before being sunk by bomber aircraft in the Mediterranean in 1942, while earlier ships of the name had succumbed to the French or Spanish in one way or another. But we did not dwell much, if at all, on these less encouraging aspects of the ship’s history. Our close links with the city of Coventry and the mere fact that the name Coventry was associated with a fine fighting record were more than enough to give us something to be proud of and a tradition to preserve. In fact, my godfather Admiral Sir Horace Law had been the gunnery officer of the Coventry in 1942 and a member of the Coventry Old Hands Association, whose members still meet annually at Coventry Cathedral to remember their lost comrades. There is a memorial to the ship in the crypt of the cathedral: my Coventry was later to be commemorated by a new memorial, next to the old one, and members of my ship’s company have now also joined the Association.

As it was, we left Gibraltar on 29 March 1982 for a few days of missile firings; we would then return to Portsmouth for some welcome leave and ship maintenance. However, we began to glean from various signals to the Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet, Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse, who was at sea with us, that a change of plan was in the air and that we might not be returning home as planned. It was all something of a mystery. The exercises continued, although we learnt that Sir John had flown home to his headquarters at Northwood. Then, on 2 April, we heard the startling news that South Georgia and the Falkland Islands had been invaded by Argentina and we were instructed to proceed south immediately and at best speed for Ascension Island. This small outcrop of volcanic rock in the South Atlantic is a British dependent territory just south of the Equator with an area of thirty-five square miles. Importantly, Ascension has an air base with a 10,000-foot runway which is leased to the United States, and it was subsequently to become an invaluable halfway staging post, anchorage, refuelling depot and transit camp.

Coventry at this time was in company with HM ships Antrim, the flagship, Glamorgan, Sheffield, Glasgow, Plymouth, Yarmouth, Brilliant and Arrow together with an accompanying Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) tanker, Appleleaf. The large destroyers, Antrim and Glamorgan, were primarily designed for the anti-surface role, each having four Exocet missile launchers and a twin 4.5-inch gun; but they also had Sea Slug and Sea Cat anti-air missiles, the forerunners of Sea Dart and Sea Wolf, and now virtually obsolete. Their Wessex helicopters were designed for anti-submarine warfare. The frigates in the group, Plymouth, Yarmouth, Brilliant and Arrow, were equipped mainly for both anti-submarine and anti-surface work. Brilliant and Arrow, being comparatively new, were fitted with Exocet and carried Lynx helicopters; Brilliant had the short-range anti-air missile Sea Wolf as well.

There were other ships in the area but they were ordered to return to England. Events were unfolding fast and our mission was now becoming a little less confused. Thoughts immediately turned to home and the effects on our families as clearly we were not now going to be back as planned on 6 April. D was in Petersfield, looking after our two daughters Miranda and Alice, then aged nine and six. I consoled myself to think that she was far from being the only one in this part of Hampshire in a similar situation. There were many other families living nearby with sons and husbands in Coventry, and in other ships which were based at Portsmouth. I had to banish thoughts of home and concentrate on my job. The captain could not be seen by his sailors to be moping.

When would we be back and what, meanwhile, were we going to be doing? No one was quite sure, but we could soon begin to guess. In any event, I was glad to be in company with some good ships whose commanding officers I knew and liked. I also knew Sandy Woodward quite well as he had been my boss for some time before and I had done business with his staff officers, some of whom I knew very well indeed. How fortunate, then, that we were to be with each other at this time and that we had operated at sea together before. There is a great strength to be gained when working with familiar ships, and the moral and professional support available in such a close-knit task group is invaluable. Furthermore, I knew from the successful weapons training we had just completed that I had a missile system which worked and, more importantly, a tried, tested and confident ship’s company of high quality. This was all very reassuring, yet the fact remained that none of us had actually been tested in war, and nor, for that matter, had any of the commanding officers in the Royal Navy at the time. A very few had been involved in putting out colonial bush fires or other such low-intensity campaigns, but that was the sum total of their experience of war.

Tradition acquires a new meaning when you are thrown into the spotlight and involved in momentous events. You become acutely aware that the reputation of both the Navy and your ship is at stake. And so the fighting tradition of the Navy sets a huge challenge for every new generation: it simply must be upheld, and this is what spurs you on. No one wants to fail or to let the side down, and nothing short of performing to the highest standards will do. The Royal Navy, after all, is accustomed to winning, regardless of the odds – and what is more, the country expects as much.

So we headed south, preparing ourselves and our weapons for any eventuality. It was a time of introspection for everyone on board, just as it was also a time for me to rally my ship’s company of twenty-eight officers and 271 ratings to the cause. I reflected on my few brushes with war in my early days in the Navy – although this present conflict, if it came to it, looked much more dangerous. I had been serving in the frigate Eastbourne as a sub-lieutenant when we steamed all the way at high speed from the Far East to the Persian Gulf during the Kuwait crisis of 1961. This was when the aggressive dictator of Iraq, General Kassem, threatened to invade Kuwait. By the time we arrived, the crisis had been speedily dealt with and was virtually at an end – much to our disappointment. In those days we had an amphibious squadron based in the Gulf which, with the help of the commando carrier Bulwark, landed the Royal Marines on the Kuwait beaches and forestalled the invasion. The excitement was over.

Later, in 1964, when I was the second-in-command of the coastal minesweeper Lanton, I had been involved in the confrontation with President Sukarno of Indonesia who was then threatening British North Borneo. Based at Tawau in the traditional gunboat role, we operated in the jungle rivers of Borneo, supporting the Gurkhas and Royal Marines who were fighting in the jungle against the marauding Indonesians. The fighting ashore was fierce at times and the commanding officer of the Gurkhas, Chris Hadow, was killed. I had been with him in his jungle base not long before to learn how the soldiers operated and how best we could support them. Keeping them supplied with cans of beer was, naturally, one of our more important duties.

In the early days, before the shooting war really started, we were ordered to anchor the ship in an open stretch of water and on the median line which marked Indonesian territory on one side and British on the other. The idea was to demonstrate to the Indonesians not far away on the opposite shore that we were intent on defending what was ours. Without warning, however, their shore batteries opened fire on the ship and we began to be hit near the stern. It takes time to haul in the cable and get the anchor up and so I went forward to supervise the breaking of the cable in order to leave the anchor, with a short length of cable, on the sea bed: this was the quickest way of getting the ship moving and out of range of the Indonesian guns. Meanwhile, we fired back with our 40-mm Bofors gun and silenced the enemy. Unfortunately, there was no time to attach a buoy to the end of the anchor cable before we let it go over the side. We got away unharmed and with no casualties – but with only one anchor remaining.

Questions were asked by the authorities back in the UK why Lanton had opened fire on the enemy, as the rules laid down by our political masters at that time did not allow it. The case made on our behalf – that we acted in self-defence – was reluctantly accepted, and from then on the rules changed and the war started in earnest. For years afterwards, though, I was pursued by letters from civil servants asking me what I had done with one of Lanton’s anchors and accusing me of being thoroughly careless. I was the person, after all, who signed for such equipment when I took up the appointment in the ship and so was held responsible. I suppose I might even have been made to pay for the anchor, which, being made of non-magnetic phosphor-bronze, was a rather expensive item. Fortunately, I never was.

Hauling myself back to the present, I could reflect on the cause of the rapidly deteriorating current situation, which largely arose from a simple failure of deterrence. In 1981, it had been decided that the twenty-five-year-old Antarctic patrol ship Endurance would be decommissioned at the end of her tour in March and not be replaced. At the same time, following a government review of defence spending, the Defence Secretary had announced cuts in the number of ships. Some were to be sold to other navies, including, ironically, those that were to prove themselves crucial to operations in the South Atlantic – for example, the aircraft carrier Invincible. Other factors were the closing of the British survey base in South Georgia, the denial of full British citizenship to the Falkland Islanders and a decision not to upgrade the Islands’ main runway.

All this had sent a strong signal to Argentina that the UK was no longer particularly interested in the Falklands and would not have the resolve to defend them. The Argentinians, who had long held to the belief that the Islands were rightfully theirs, seized the opportunity of taking and, so they hoped, retaining possession of them. The world no doubt thought that the last post had been sounded over yet another far-flung corner of the British Empire. But the world was wrong.

CHAPTER 2

PREPARING FOR WAR

Just before we turned south, we received a signal instructing all the ships in our group to pair up with those returning to England and obtain any stores from them that might be useful. We were paired off with Aurora, an anti-submarine frigate commanded by Commander Tony Wilks. A few hours were spent steaming close alongside her, with a thirty-foot gap between us, while we transferred various spares and essential stores by jackstay, a taut line connecting the two ships with a pulley system to which loads were attached and hauled across by hand. Aurora was a completely different class of ship to us, carried dissimilar weapon systems and was powered by steam rather than gas turbine. So there was not much she had in the way of spare parts that were compatible with Coventry. But we robbed the ship of all kinds of victuals and food that we knew would be needed for any prolonged time at sea. This manoeuvre was an inspired piece of planning and the first of the many displays of initiative and opportunism throughout the Task Force which were so vital in keeping us fighting fit and the enemy at bay.

The ships were a hive of activity and the sky was almost black with helicopters transferring stores. Many fond farewells were exchanged with friends across the narrow gaps between the ships before we turned away towards the unknown. It felt like a lifeline was being broken as we watched the ships going home until they disappeared over the horizon: they were the last link with a safer world. The happy and carefree weekend in Gibraltar already seemed a distant memory. I remembered that I had sat in the sun in the centre of the Old Town the day before sailing while I wrote a cheerful postcard to D and the girls. At least, I thought now, they will have had some recent news from me.

I had, in fact, managed to scribble a hasty letter to D which I transferred to Aurora for posting when she got back to the UK: ‘We are off southwards because of the Falkland Island situation – a large group of us. I feel very sad not to be seeing you on 6 April. This is where you have to be a long-suffering and patient naval wife. Shall always be thinking of you and the girls very much. Keep writing because we may be able to get some mail.’ I also enclosed a letter to Miranda and Alice: ‘Mummy will have told you that my ship will not be back for a few weeks yet. I hope you will always help Mummy when I am not there because she has to do a lot more work without me there. Please write to me often as I always long to hear how you are.’

Our rendezvous with Aurora had not only provided us with a multitude of food and stores but had also enabled me to solve a potentially difficult personnel problem. I had five sailors on board who had family concerns back home or important events planned: one, for example, was due to get married and all the arrangements had been made. I was very aware that these men and their families would be very upset if they could not get back to the UK and that their work on board might suffer as a result. Above all, I wanted a contented ship’s company. The men could, of course, return home in Aurora, but only if I could trade them in for sailors with the same rate and qualifications who would transfer to Coventry.

Remarkably, Aurora produced five enthusiastic volunteers to sail with us who exactly matched the skills of the sailors who would go home. I fervently hoped they would be happy in Coventry and pull their weight. Much later, after the war had ended, Tony Wilks, Aurora