10,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

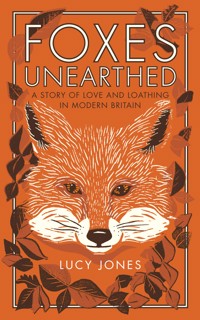

As one of the largest predators left in Britain, the fox is captivating: a comfortably familiar figure in our country landscapes; an intriguing flash of bright-eyed wildness in our towns. Yet no other animal attracts such controversy, has provoked more column inches or been so ambiguously woven into our culture over centuries, perceived variously as a beautiful animal, a cunning rogue, a vicious pest and a worthy foe. As well as being the most ubiquitous of wild animals, it is also the least understood. In Foxes Unearthed Lucy Jones investigates the truth about foxes in a media landscape that often carries complex agendas. Delving into fact, fiction, folklore and her own family history, Lucy travels the length of Britain to find out first-hand why these animals incite such passionate emotions, revealing our rich and complex relationship with one of our most loved – and most vilified – wild animals. This compelling narrative adds much-needed depth to the debate on foxes, asking what our attitudes towards the red fox say about us – and, ultimately, about our relationship with the natural world.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

‘A sensitive and illuminating investigation into our complex and ever-evolving relationship with the most intriguing, incredible and intractable of British mammals. Through a keen eye and bright prose, Jones traces the trail of the fox through history, myth and current debates, exploring the roots of our love and hate from all perspectives. This is a beautiful book that will change the way you think about the fox, whatever you think about the fox’

—ROB COWEN, author of Common Ground

‘A fantastic tour of the fox and us – Lucy Jones takes an intelligent, measured and humane look at the intimate, contradictory and occasionally crazy relationship between Homo sapiens and Vulpes vulpes’

—PATRICK BARKHAM, author of Badgerlands and The Butterfly Isles

‘A foxy little book, offering a rich brew of nature and history and culture. An exemplary instance of fine research leading to balance and sanity on a subject usually lacking in either. Deeply enjoyable and informative’

—SARA MAITLAND, author of Gossip from the Forest: The Tangled Roots of Our Forests and Fairytales

‘Lucy Jones’ investigative study explores the romantic myth and harsh reality of the fox with the unflinching rigour of a true journalist and heart of a poet’

—BENJAMIN MYERS, author of Beastings and Pig Iron

‘Brave, bold and honest – finally the truth about foxes’

—CHRIS PACKHAM, broadcaster and naturalist

Contents

Prologue

1 As Cunning as a Fox

2 Fox in the Henhouse

3 To Catch a Fox

4 Tally Ho!

5 Friends and Foes

6 The Fox Next Door

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Index

Prologue

Of all the mammals in Britain, it is the fox that has cast its spell on me. I find it, as one of the largest predators left in our islands, a captivating creature: a comfortably familiar figure in our country landscapes; an intriguing flash of bright-eyed wildness in our towns.

It is an animal that is often surrounded by myth and controversy, and my own experiences of the fox have proved just as complicated and conflicting. Traditionally, one side of my family had a fondness for hunting – particularly my late grandfather, whom I adored, admired and respected. In my early years, fox hunting was an accepted part of life. It was only as I grew older, and my own partiality for the fox began to emerge, that I started to question the activity. The fox, in my experience, has always been more than just a wild animal. He is a character, an emblem, a flint for emotions and ethical questions; in short, he poses something of a quandary for us here in Britain, in both town and country.

As a reluctant city-dweller, I’m no stranger to glimpsing foxes on our streets – as townies we may not have otters or hares or ptarmigans or capercaillies, but we do have Vulpes vulpes in abundance. It had been a while since I’d spotted one, though, and I decided to walk through Walthamstow Marshes in London, the nearest large green space to my home, to see the animal in action. The area is a biodiversity hotspot, home to flowers, plants, insects and voles. Two pairs of kestrels had moved in, and they hovered and dived like feathered meteors into the marshlands.

To up my chances, I turned to Fox Watching by Martin Hemmington, a practical guide for would-be ecologists. First, keep eyes and nose peeled for hair, droppings, paw prints and the smell of urine. Second, wear camouflage clothes with black or brown shoes. Third, bring binoculars, writing equipment and dinner. Fourth, patience is essential. I left the house before dusk armed with new knowledge and a slice of spinach pie in my pocket. As the air cooled, the scent of the marshes intensified. Large slugs with patterned backs slithered in scores across the path – food for foxes, if they fancied it. The lights of a train lit up the trail as I walked into the undergrowth, looking for vulpine scat and hoping a fox would cross my path.

As it turns out, though, foxes can be elusive creatures when you’re in active pursuit, and my search proved frustratingly fruitless that night, as did many that followed. For some reason, our paths were just not crossing. I was beginning to think the fox population in our cities was being grossly exaggerated.

When I finally did stumble across a fox, it was completely by accident. I was ambling home through busy, built-up Stoke Newington, my mind elsewhere, certainly not on foxes. And suddenly, there it was. It emerged gingerly at first, peeking through the railings of a railway bridge. Standing on the pavement by a busy crossroads at around eight o’clock in the evening, close to shops, restaurants, pubs and houses, it waited for the traffic to clear, its head turning back and forth, eyes following the cars, ears pricked. Its brush was long, full and rich, slightly darker than the rest of its pelage, and turned up at the end at a jaunty angle. It crowned a long, lithe body, its wintry fur coat a rusty, burnt ochre. The fur on its throat was white, giving the impression it was wearing a bib. We made eye contact; it looked intelligent, curious, for the most part nonchalant. Its eyes were an amber gold, lit up by the headlights, expressionless and cool. Around the muzzle and those sharp teeth, the fur was white. I wanted to get closer but, wary of spooking it, hung back to keep it in my sight as long as possible. It soon trotted off and vanished through the gate of an apartment complex.

Even though I’d seen lots of foxes over the decade I’d lived in London, I experienced a jolt; a pure, chemical thrill. Various associations rushed through my head – memories of taxidermied fox heads in my grandparents’ house, Fantastic Mr Fox, the vulpine ‘psycho’ killer of a recent news report, Ted Hughes’s bold and brilliant Thought-Fox – and I felt excitement, wonder, surprise. Yet I knew my reaction wouldn’t have been universal.

When you see a fox, what do you feel? More than any other animal in Britain, the fox can elicit a cocktail of opinion and emotion. It is rarely a blank canvas. Perhaps you see the fox as vermin, a pest to be shot as quickly as possible, a rude interloper who doesn’t belong in the human space. Perhaps you see a beautiful wild animal or a cute pet to be fed. Or perhaps you see a cunning rogue waiting to be hunted. You might feel annoyed if a fox once killed your chickens or your pet tortoise. You might feel elated to witness the largest British carnivore so casually on a street corner. You might even feel a little frightened, a natural response to coming face to face with what is still a wild animal.

In his book Arctic Dreams, Barry Lopez remarked vividly on the sensation of human–animal collision. ‘Few things provoke like the presence of wild animals. They pull at us like tidal currents with questions of volition, of ethical involvement, of ancestry,’ he wrote. The currents that exist around the fox in Britain are powerful, old and complex. They have combined to create an enigmatic character, rarely perceived for what it actually is.

The fox has come to represent a thorny and emotive array of concepts to different people: from liberty to beauty, class to cruelty, hunter to hunted, pin-up to pest. In no other culture but Britain’s is the animal so polarising and so complex a public figure, perceived ambiguously by its human neighbours, on both a local level and in national debate. No other creature in Britain has provoked or inspired more column inches, literary characters, pop-culture symbols, parliamentary hours, lyrics, album covers, cartoons, nicknames, pub names, jewellery, tea coasters, cushion covers, Facebook fights, hashtags, demonstrations, rallies, words and sheer cortisol than the fox. Former prime minister Tony Blair described the passions aroused by fox hunting as ‘primeval’. ‘If I’d proposed solving the pension problem by compulsory euthanasia for every fifth pensioner I’d have got less trouble,’ he wrote in his memoirs about the row over Labour’s Hunting Act, which banned hunting wild mammals with dogs.

The conflicting emotions – passionate love and hate – that the fox inspires is a fascinating phenomenon. To understand fully how attitudes, experiences and agendas collided to create this peculiar variation in our feelings towards Vulpes vulpes, we must delve into the history of the fox in Britain and how our relationship with this wily mammal has evolved over millennia.

1

As Cunning as a Fox

The cerulean sky set everything off the day I travelled to Great Missenden, the little country village in the Chilterns made famous by its erstwhile resident Roald Dahl, to visit his archives. Trees were slightly burnished by the beginning of autumn and leaves browned like the top of an apple crumble. The houses became quaint and pretty as the train whizzed out of London.

Dahl was born in Cardiff in 1916 to Norwegian parents. He started writing during the Second World War and, in 1943, The Gremlins was published, the first of a run of funny and imaginative stories published in hundreds of languages. Unlike other children’s books, Dahl’s writing was never didactic or moralising; he revelled in high jinks and naughtiness. ‘I am passionately obsessed with making the young readers laugh and squirm and love the story. They know it’s not true. They know from the start it’s a fairy tale, so the content is never going to influence their minds one way or another,’ he once said.

The author’s writing hut has been replicated exactly in the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre. His ashtray, complete with cigarette butts, sat on the makeshift desk that rests on an armchair made specially to accommodate his back problems. Spectacles and other personal items were nearby: family photos, drawings, trinkets, lighters, mementoes. The lino is as it was: blue, red and yellow diamonds on a green background. It’s the same lino filmmaker Wes Anderson gave to the study floor of his Mr Fox in the popular film based on the book. Dahl sat in his hut from ten in the morning until twelve, even when stuck, to write. ‘It is my little nest, my womb,’ he said. From there he could see down to an ancient beech called the Witches’ Tree – the very one where he imagined a certain Mr Fox and his family lived.

The most famous fox in British literature today emerged in 1970. Dahl’s Fantastic Mr Fox was a complete transformation in the way foxes are perceived in this country – traditionally seen as a wicked trickster, he now became the first unequivocal fox hero. The very fact that a new vision of the fox had appeared provides fascinating insights into the tensions around the fox’s place in Britain.

The plot of Fantastic Mr Fox sees our hero as a predator to be admired. With the fox family being relentlessly hunted by three nasty farmers, Mr Fox comes up with the idea of taking food from each of their farms through a series of underground tunnels. He gathers a vast feast for all the other families trapped by the farmers’ determination to kill the crafty fox, and for that he is dubbed fantastic. Dahl created characters and a plot that make us delight, cheer and punch the air when the foxes outfox the repulsive farmers and feast on livestock and poultry to their hearts’ content.

In the archives I discovered that the first draft was different from the story we know today. The foxes – and Dahl’s original drawings of them are charming – dig up into the Main Street supermarket and fill their trolleys with cake and eggs and pie and candy and toys. Mr Fox is still the provider, but the family is essentially stealing from faceless shopkeepers. ‘The cops are still looking for the robbers,’ reads the final line.

The American publishers were concerned that this ‘glorification of theft’, as Roald Dahl’s biographer Donald Sturrock put it, would put off libraries and schoolteachers from promoting the book. Editor Fabio Coen wrote to Dahl with a suggestion. Instead of stealing from the supermarkets, the foxes should steal from the horrible farmers. ‘It would also hold something of a moral,’ he wrote. ‘Namely that you cannot prevent others from securing sustenance without yourself paying a penalty.’ Dahl was thrilled with his editor’s ingenuity. ‘I’ll grab them with both hands and get to work at once on an entirely new version,’ he wrote. Later, there were conversations about whether the fox really needed to kill the three chickens in the coop, and a suggestion was made that the fox should just collect a huge basket of eggs instead. Dahl insisted that this would not be right. ‘Foxes are foxes and as you’re right to say they are killers,’ he explained. The decision was made that it wouldn’t distress children and the foxes’ natural activity was kept in. Fox is a hero in spite of his natural carnivorous behaviour. He is cunning, and he is celebrated for it.

I wandered to the field near Gipsy House, where Dahl and his family once lived, to see the beech trees under which the real Mr Fox built his den. Hedgerows covered in clots of red hawthorn berries and blackberries the colour of dried blood bordered the footpath. Summer was over and the honeysuckle looked ropey. The late-afternoon September light made the foliage glow green and dappled the damp forest floor. It was quiet and seemed a fitting place for a fox family to make its home.

Dahl would have been well aware as he was writing that he had chosen an animal whose image was starting to be fiercely contested, that perhaps it was now ready for a more sympathetic portrayal. Although he never spoke publicly about fox hunting during his life, when he was sixteen and boarding at Repton School in the Midlands, he wrote an essay about hunting. The archivist at the Roald Dahl Museum dug it out during my visit. It is a forcible argument for why Dahl believed hunting to be ‘foolish, pointless and cruel’. He concedes that riding a horse is enjoyable but questions the need to have ‘something to chase, something at which to shout and blow trumpets . . . and finally to satisfy their bloodthirsty minds’. The red fox is described as ‘small’, ‘valiant’ and ‘little’; he ‘tires’ and ‘takes shelter’. Dahl recounts what happens if the animal is found: ‘Slaughter takes place, after which certain young and usually too well-nourished members step forward to have the blood of sacrifice smeared on their faces.’ Dahl’s visceral and imaginative wit shows early: the huntsman has the appearance of ‘having been grown in the dark’.

Dahl then draws a comparison between the killing of the fox and the lady who cries when her Pekinese gets a thorn in its paw. It is ‘incredible’, he writes, that the same lady should gloat at a fox being ‘torn to pieces’. The piece ends with the assertion that the most humane method of killing foxes is surely to shoot them. Although views do, of course, change, it is still an interesting insight. We know Dahl was an animal-lover: he owned dogs, cats, goats and even 200 budgerigars at one point, and in his book The Magic Finger, published in 1966, a young girl who abhors hunting uses her magic to turn a local hunting family into the ducks they shoot.

Compare Dahl’s portrayal of the fox, a noble and sympathetic creature, with another: licking his lips, eyes narrowed and thickly kohled beneath comic, angry eyebrows, often surrounded by a cloud of feathers, the fox is unequivocally dangerous, but also clever, and therefore a worthy opponent for sport. He even has a name: Charlie. This is the fox of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and if you read the classic hunting literature, you’d believe this fox is more attractive than the average town fox you might see today: richer in hue, it could be mistaken for a flame if you caught a glimpse of it across a field. He was distinguished from other animals by his cunning – he could roll in manure so that the hounds would lose his scent or run across bridges or swim across lakes. In a way, he was master of his own destiny. Some sources even suggested Charlie enjoyed being hunted, looking back at the hounds with a smile and a chuckle.

When I see a fox, I’m aware that I am utterly influenced by the stories I’ve been told, the pictures I’ve absorbed, the rumours I’ve heard. Foxes have a rich history in this country, as a creature we have used for our own physical needs, as fur, food or medicine, but also as one that has captured our collective imagination, at various times a rogue, a villain, a trickster, a character to be admired or reviled.

But what, fundamentally, is the fox? Above all, it is a brilliant opportunist, capable of exploiting a huge range of ecological habitats and environments, and this is one of the reasons why it is so widespread around the world. It has colonised most of the northern hemisphere with a greater geographical range and concentration than any other carnivore on earth. Altogether, there are twelve distinct species of fox, each adapted to its environment, from the tiny, delightfully big-eared fennec (Vulpes zerda) of the Sahara desert to the snow-white, fluffy-bodied Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus), found in colder climates such as Iceland. But it is the red fox that is indigenous to Britain.

The most instantly striking characteristic of this animal is its colour. The red fox is, as its name suggests, a vivid, bright shade of reddish orange, a startlingly eye-catching hue that varies in intensity from pale apricot via ruddy red to the fiery orange of volcanic lava. The fur on the neck and chest is softer, fluffy and white as is, usually, the bob on the end of the brush. Its legs, brush and the hairs on its ears will also be tinted with black. Occasionally ‘black’ red foxes have been spotted, as the amount of darker fur varies from animal to animal. The red fox is long, thin and surprisingly small, on average only between 46 and 86 centimetres long, excluding the tail which can be another 30 to 55 centimetres.

The face of a fox is mesmerising – handsome, even. The ears are prominent, triangular, adorable, with soft black or white hair tufts inside. The eyes are an extraordinary gold colour, quite light and shaped like a cat’s, and its expression is naturally alert, conscious – even clever, especially when it narrows its eyes.

Animals cannot speak and so we speak for them. Across Europe, one of the enduring perceptions of the fox lies in the idea of vulpine intelligence. It has existed for centuries, millennia even, and has been one of the animal’s defining characteristics, from the human point of view, although with varying interpretations and ramifications over the years.

More than 2,500 years ago, in Ancient Greece, a slave called Aesop created what would become a long-enduring representation of the fox. Aesop supposedly came up with hundreds of fables, which were short and to the point, sometimes just a couple of sentences long, mostly about animals, and often including a moral lesson about human behaviour. For a number of them, his authorship is debatable: some have roots in Indian, Talmud and various folkloric traditions. In any case, the fox is a recurring character in his stories, and a clear picture of the fox’s characteristics quickly appears.

In one tale, the fox leads the newly crowned king ape to a baited trap; the ape accuses him of treachery. In another, a crow has found a piece of cheese and retires to a branch to eat it; the fox flatters her by asking if her voice is as beautiful as her looks; the bird sings and drops the cheese into the fox’s mouth. A lion is pretending to be sick to lure animals into his cave; the fox hangs back – he can see paw prints only going in, not coming out; he survives. A lion and a bear fight each other for a young fawn; the fox waits until they fall asleep from exhaustion and sneaks in to snaffle their prey. A fox enters the hollow of a tree to eat food left there by a shepherd; he eats so much, he is too fat to escape. A fox tries to reach grapes but he’s not tall enough. A fox tries to eat soup from a stork’s bowl but it’s too narrow.

Aesop’s stories reveal a couple of common threads. First, the fox was perceived to have an appetite, and he is prepared to step into other animals’ spaces to get a meal. Second, he is able to get this food through trickery. He can think ahead and use his wits to protect himself. And, crafty and elusive, he is often successful. The fox’s wits are referred to using the Greek word poikilos, which means something difficult to define, varied, manifold, of different colours and shades. A shape-shifter, in a way. The fox, according to the earliest fables, was smart.

It is worth taking a moment to examine what is understood by ‘intelligence’ in a fox, and whether there is truth to the reputation that the fox is cleverer than other animals. Canids have high levels of cognitive ability, as many social animals do. The fox is an adept hunter, successfully resourceful, opportunistic and adaptable to different environments. Evolutionary pressure has made the species adept at assessing and exploiting availability. ‘The fox can make decisions quickly and solve problems to get food,’ explained Dr Dawn Scott of the University of Brighton, who has studied canids for decades, and the red fox in particular. ‘That ability to exploit and adapt means that natural selection has driven it to be able to solve problems. And that’s how we assess intelligence: ability to solve problems.’

There are certainly examples of what we might consider clever behaviour. Aelian, the Roman author writing around 200 AD, gives an early account of a fox’s ability to trick. A fox could sneak up on a bustard, a large terrestrial bird common on the steppes of the Old World, by raising its tail and pressing the front of its body to the ground, it could artfully change itself into a persuasive silhouette of the bird.

One of the most famous tactics the fox is said to deploy is that of playing dead, either to escape capture or to outwit prey, and there have been many examples of this in literature and art over the centuries. The Physiologus, a second-century Christian text, tells of the fox feigning death: ‘When he is hungry and nothing turns up for him to devour, he rolls himself in red mud so that he looks as if he were stained with blood. Then he throws himself on the ground and holds his breath, so that he positively does not seem to breathe. The birds, seeing that he is not breathing, and that he looks as if he were covered with blood with his tongue hanging out, think that he is dead and come down to sit on him. Well, thus he grabs them and gobbles them up.’

In January 2016 the ruse was actually caught on film. Siberian hunters came across what appeared to be a dead Arctic fox, trapped in one of their snares. The video shows the fox being manhandled as they remove the snare; it never flinches, its eyes remain closed and face motionless. It looks utterly dead. But almost as soon as the men place the body in a cardboard box, the fox bursts out, leaps high into the air and scrambles across the snow for its life, soon to be joined by a group of Arctic fox pals. It is a stunning sequence of supposed thought, ingenuity and wits.

Another folkloric tale of the fox’s intelligence is that the fox, if troubled by fleas, takes a piece of wool in his mouth and trots to the nearest river for a cooling swim. The fleas, desperate to avoid drowning in the water, congregate on the strip of wool. Once they’re all in one place, the fox releases the wool into the river, thus getting rid of his unwelcome guests. It is a common tale in different parts of the world and we don’t know the exact origin: it was popular in Celtic communities but there’s a similar version about a jackal in India. Even though it’s unlikely to be true, the tale still exists today; it was recounted to me as fact by a man in the Lake District in 2015.

Partly as a result of its supposed intelligence, the fox has often been seen as a threat to human interests. While it would not have been in direct competition with humans for food in the remote past, a major change for the fox, and for other wild mammals, occurred when domestic livestock was introduced – in Britain, the earliest sheep are dated to over 5,000 years ago.

The fox had been around for many thousands of years – the oldest fox remains in Britain date back to the Wolstonian period (between 130,000 and 352,000 years ago) from Tornewton Cave in South Devon. Remains of wolf, lion, badger, bear, horse, reindeer, clawless otter, rhino and bison were also found in the same stratum so we can imagine a countryside teeming with mammals of all shapes and sizes, alongside the fox. With other such predators around, the fox would have found itself in competition for food, and it would even occasionally have become prey to an opportunistic bear, wolf or lion. But it also would have posed only a secondary threat to humans.

As the ice sheets melted at the end of Europe’s final glaciation, around 12,000 years ago, vegetation gradually became more abundant across Britain as the land began to blossom into a scene more familiar to us now, allowing the wildlife, including foxes, to flourish.

But it was with the shift to a farming culture that foxes started to cause a problem for human settlements. An animal with an omnivorous diet, the fox would have been partial to a grape or two, so in direct competition with early farmers for the food they were cultivating, as well as to their livestock.

At first, the fox might have benefited from its new barnyard neighbours. It was much easier for people to eat their domestic animals than go hunting with snares, traps or spears, and the fox wasn’t as much of a threat to sheep, cattle, goats and pigs as were bears and wolves. While the bigger mammals were still roaming the countryside, the fox could keep a low profile, even though its population was widespread across Britain.

The earliest and clearest account of the fox troubling livestock is from Pliny the Elder. A Roman naturalist and scholar writing in the first century AD, he suggested practical methods for farmers to keep foxes at bay. One simple solution, for example, was to feed chickens the fried liver of a fox, which would prevent them from being attacked. A slightly more complicated way of protecting one’s hen involved cutting a collar of skin from the neck of the fox and affixing it to a cockerel’s neck. The hens that mated with the cock thus adorned were immune from being hunted and killed by the local fox. Presumably there is some logic to this: foxes are territorial and mark their territories with scent from their various glands. Foxes observed in areas of Britain by the eminent Scottish biologist and zoologist Professor David Macdonald of Oxford University would very rarely cross boundaries laid down by another fox group even if food was available. A fox might have been so put off by the smell of the makeshift necklace that the poultry was given wide berth.

Fear and apparent threats to human lives or settlements – such as wild animals – are powerful. They have a way of gripping our collective imagination, entering our storytelling traditions and gradually becoming increasingly magnified to the point where they can transform into an enemy of mythic proportions.

And the fox is indeed presented as menacing in early European myths and stories. In Greek mythology, for example, the Teumessian fox, also known as the Cadmean vixen, was an enormous fox that could never be caught. The vixen, which had been sent by the gods as punishment for an unrecorded crime, plagued the population of Thebes by eating people’s babies. Eventually, the beast was stopped when the dog Laelaps, who could always catch its prey, was brought in to pursue the fox. Faced with an impossible paradox, Zeus turned both creatures into stone and flung them into the skies – where they remain to this day as the constellations Canis major and Canis minor.*

The fox’s perceived intelligence, when exercised in competition for food, might be interpreted as devious rather than smart. Between admiration for that cunning and dislike for the fox’s thieving tendencies, the ambiguous relationship humans have developed with the fox emerged fully in the popular culture of the Middle Ages. The hugely popular and influential stories of Reynard the Fox acknowledged his sneaky habits, but also seem to display a grudging respect and admiration for the animal.

It is unclear who invented the character of Reynard, but versions of the story were certainly popular around Europe. In the preface to German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s epic poem Reineke Fuchs (1794), he suggests that the first account was by Nivardus, a Flemish ecclesiastic attached to the monastery of St Peter at Ghent in 1148. Different accounts of Reynard spread through Europe, following Pierre de Saint-Cloud’s Roman de Renart during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries with Die Hystorie van Reynaert die Vos published in Dutch in 1479, from which William Caxton took his first English translation of 1481. In an early illumination from the manuscript of Roman de Renart, in the thirteenth century, a fox sits upright on a horse, wearing armour and an orange cape. His eyes look slightly upwards as he plunges his sword into the heart of Ysengrim the wolf. In another image from later in the same century, a large fox, with a goose in its mouth, leaps away from a woman. The goose’s head flops out of the fox’s jaws; his claws look sharp and dangerous. You can almost see the bubbling white saliva dripping from his teeth. The eyes are narrowed and elongated, seeming to denote wickedness.

The general plot of Reynard is quite simple. It begins in the court of King Noble, a lion, where locals have turned up to complain about Reynard’s anti-social behaviour. He blinded my cubs, says Isegrim the wolf. He nicked my pudding, says Courtuys the dog. He ate my chicks, weeps Chanticleer the cock. The King summons Bruin the bear to bring Reynard in. Reynard agrees to go with Bruin to court, but, before they leave, he wonders whether the bear might like a taste of honey? Bruin sticks his head in a log, where it gets stuck, and rips off half his face and his ears trying to get free. Reynard 1, King 0. Then, Tybalt the cat is sent to get Reynard. He returns with one eye. Reynard 2, King 0.

Reynard eventually relents and goes to the King, and the rest of the story is a dialogue between the two in which Reynard’s dirty work is discovered but wriggled out of with an imaginative lie. He succeeds by outwitting the other animals with cunning tricks that play on their weaknesses. He bullies, he kills, he wins.

Reynard was a bestseller in the Middle Ages and has been rewritten and translated a number of times since. Its popularity may have been due to it fulfilling a need: medieval beast fables were usually not about animals, but about humans and human relations, using animal characters to satirise human society as well as personifying certain traits and emotions. As Joan Acocella wrote in a New Yorker essay, ‘Animals are fun – they have feathers and fangs, they live in trees and holes – and they seem to us simpler than we are, so that, by using them, we can make our points cleaner and faster.’ Creating a story around animal characters engaged people, while also carrying a moral or deeper meaning.

The character has gone on to inspire tales in different art forms, from Stravinsky’s opera-ballet Renard to Ben Jonson’s Volpone, from the stories of Chicken Licken to Janáček’s Cunning Little Vixen. In the nineteenth century Reynard was the basis for the ballad of Reynardine, a werefox who lured beautiful women to his castle, to an undisclosed fate. He’s even been immortalised in British hunting songs – and, indeed, ‘Reynard’ is still a name for a male fox in the UK:

On the first day of Spring in the year ninety-threethe first recreation was in this country,the King’s County gentleman o’er hills, dales and rocks,they rode out so jovially in search of a fox.

Chorus: Tally-ho, hark away, tally-ho, hark away,tally ho, hark away, boys, away.

When Reynard first started he faced Tullamore,Arklow and Wicklow along the seashore,he kept his brush in view every yard of the way,and it’s straight he took his course through the streets of Roscrea.

Chorus

But Reynard, sly Reynard, he lay hid that night,they swore they would watch him until the daylight,early the next morning the woods they did resound,with the echo of horns and the sweet cry of hounds.

Chorus

When Reynard was started he faced to the hollow,where none but the hounds and footmen could follow,the gentlemen cried: ‘Watch him, watch him, what shall we do?If he makes it to the rocks then he will cross Killatoe!’

Chorus

Bur Reynard, sly Reynard, away he did run,away from the huntsman, away from the gun,the gentleman cried: ‘Home, boys, there’s nothing we can do,for Reynard is away and our hunting is through.’

Chorus

In 2014, the first series of Bosch, a noir detective TV drama set in Los Angeles, had as its villain one ‘Raynard Waits’, a pseudonym devised by the character. Michael Connelly, from whose novel the TV show was adapted, made his Raynard crafty and apt to change his appearance, a direct reference to the character traits of the Flemish tale. Both have the same raison d’être: to prey and outwit. Waits, now on the run, calls Bosch (King Lion) to confess, to trick, to wind up, delighting in the fact he has one up on the police as he goes around murdering prostitutes and adding to his skull shrine. Reynard lives on in human form.

Mostly, Reynard is a villain we cheer for. The Caxton translation is written with a delight at the character’s Machiavellian quality: we enjoy watching the play of intelligence in contrast with the stupidity and gullibility of the other animals. It is inconsistent, though. On the one hand, the reader is invited to enjoy Reynard’s outrageous lies and one-upmanship over his boorish peers. ‘An ass is an ass,’ says Reynard. ‘Yet many have risen in the world. What a pity.’ And we can’t help but agree. On the other, his activity is violent: he rapes the wolf’s wife and causes many a gory injury. Caxton, towards the end of the epic, warns against such behaviour and suggests we weed out character defects similar to the ones the fox displays. Yet, it all ends happily ever after for Reynard, which suggests he is, if not the hero, at least an anti-hero. He is charismatic, and, to use Colin Willock’s phrase, ‘splendidly nefarious’.

Reynard was not the only fox story of the times. Chaucer wrote a cunning fox, Russell, into his Canterbury Tales. His was a retelling of Aesop’s ‘The Fox and the Crow’, which further popularised the story in Britain. This was in the 1390s, when Britain was experiencing harsh weather, with savage winters and wet summers, which would have put increasing pressure on food production, and people were badly malnourished. The country was also still recovering from the Black Death epidemic in 1348, which had wiped out half of the population. Any predatory mammal would have been seen as a threat to human sustenance. It was at this time that Chaucer’s Russell, in the Nun’s Priest’s Tale, is ‘full of sly iniquity’ and lurks in a bed of cabbage with the intention of taking Chanticleer the rooster. He manages to make off with the bird after convincing him to close his eyes and sing, although the rooster escapes in the end.

In a practical sense, tales about pilfering foxes gave instruction to farmers about protecting their livestock. But the fox had also become a clear symbol for a variety of moral failings. As most people were illiterate, such a message could be communicated quickly and clearly through imagery, which more often than not would be conveyed through the Church, the main source of information for many.

The Church already had a long history of portraying the fox as a villain, going back to early descriptions in the Bible. It appears as a thief: the author of Song of Songs, thought to have been written around 200 BC, accuses the fox of ruining vines. And in the Gospel of Luke from the New Testament, Jesus refers to Herod Antipas as ‘that fox’ after he is warned of Herod’s plot to kill him, painting the king as a crafty enemy intent on entrapment. The fox’s reputation as cunning and deceptive is also equated with false prophets in the Old Testament Book of Ezekiel: ‘O Israel, your prophets are like the foxes in the deserts.’ In John Gill’s Exposition of the Old Testament, from the eighteenth century, he explains that these false prophets are ‘comparable to foxes, for their craftiness and cunning, and lying in wait to deceive, as these seduced the Lord’s people; and such are false teachers, who walk in craftiness, and handle the word of God deceitfully, and are deceitful workers; and to foxes in the deserts, which are hungry and ravenous, and make a prey of whatsoever comes within their reach, as these prophets did of the people.’

These early biblical references to the fox inform the Church’s representations of the fox in the Middle Ages, which also tie in with the popular portrayals of the sneaky Reynard character, a familiar image that people would recognise and understand.

There are various examples of the way the fox was depicted in ecclesiastical iconography throughout the Middle Ages. Firstly, as a simple thief – possibly as a cautionary tale to the local community. In Wells Cathedral, a carving that dates to 1190 shows a fox stealing a goose, inspired by early versions of Renard the Fox and Chanticleer. Sometimes the fox was shown as slinging the goose over its back, a common image in wood carvings across Britain. Although there is anecdotal evidence of people witnessing a fox carrying a goose on its back, this seems extremely unlikely – a fox tends to carry prey in its mouth, often clamped to the head or neck. It is a depiction based on myth rather than observation.

As a myth – as a symbol – the fox had already come to represent the devil in medieval bestiary accounts – those tales with a moral message that usually described animals and their characteristics. ‘The fox signifies the Devil in this life,’ wrote Philippe de Thaun in the twelfth century. ‘To people living carnally he shows pretence of death, till they are entered into evil, caught in his mouth. Then he takes them by a jump and slays and devours them, as the fox does the bird when he has allured it.’

Gradually, the early biblical comparisons of the fox with false prophets also started to become increasingly popular as visual representations, with the fox portrayed as a devil preacher. ‘When the fox preaches, beware your geese,’ says the proverb. The commonly occurring theme of the fox preaching to geese is partly a satire on false preachers and partly advice to avoid them, with the advent of the Lollards, a rebellious group that appeared in the 1330s, calling for reform of the Church.

In a scene from a French manuscript from the end of the thirteenth century or the first quarter of the fourteenth century, a fox stands on its hind legs, propped up by a bishop’s crozier. His long brush trails behind him and his chest is typically whiter, or at least paler, than the rest of his orange body. He wears a bishop’s mitre and his tongue is lolling out, which gives the impression he is hungry, predatory, salivating and out of control. He is standing before a group of birds: a falcon, chicken, geese, a stork and a swan, his ‘congregation’.

The Stained Glass Museum of Ely Cathedral has a couple of ‘devil preacher’ scenes in its collection. One, from the late fourteenth century, shows a fox wearing a mitre and dressed up in priest’s robes, preaching from a pulpit. The fox has his mouth open with his teeth bared. He looks as if he’s smiling and has a slightly psychotic air. The eyebrows are low and deviously angled. He lifts up his clawed hands; one is already clutching a dead goose, his ‘fingers’ gripping tightly around its neck. He looks out onto a rural scene with a couple of gormless-looking geese, the implication being that they won’t be around for much longer. The fox looks frightening, in control and definitely an enemy. The roundel was from Holy Cross in Byfield, discovered in the rectory but probably its original location was in the church.

A similar scene is found on an Ely Cathedral misericord: a fox in a preacher’s gown gets close enough to the birds in his congregation to make off with one of them. He is on his hind legs, facing four geese who look enraptured by his sermon. It is a common image in medieval art, found in tapestries, stained glass, drawings, paintings, manuscripts and wood carvings across Europe and in the cathedrals of Bristol, Worcester and Leicester, as well as many parish churches including Ludlow, Beverley and Yorkshire, and at St George’s in Windsor. The fox is depicted most often as a bishop but also as a pilgrim, priest, friar, monk or abbot. He always looks sly, crafty and cunning.

The fox remained a beguiling and mysterious animal, a competitor, a predator, a creature little understood and approached with wariness and reluctant admiration. It loomed large in the medieval imagination as a symbol for many of society’s ills. Gradually, that started to become expressed through our language.

The first example of the word ‘fox’ being used to denote artfulness or craftiness is from the late twelfth century, from verse in The Ormulum by a monk known as Ormin (‘Þatt mann iss fox and hinnderrзæp and full off ille wiless’). By then, ‘foxly’ was used to mean crafty or cunning. The verb ‘to fox’, meaning to trick by craft, appeared in 1250, and there was also ‘to smell a fox’ (to be suspicious) and ‘to play the fox’ (to act cunningly) – it is possible that the Irish word for ‘I play the fox’, sionnachuighim, is where the word ‘shenanigans’ comes from. In recognition of its thieving tendencies, there’s even the word ‘vulpeculated’, which specifically means to be robbed by a fox.

There are many other related phrases in English dialect, mostly picking up on the animal’s negative connotations in popular tradition: to ‘box the fox’ means ‘to rob an orchard’, while a ‘fox-sleep’ is a ‘feigned sleep’. But there are some that are neutral, and even quite charming: ‘foxes brewings’ means ‘a mist which rolls among the trees on the escarpment of the Downs in unsettled weather’.

Around Tudor times, a new connotation arose in the phrases ‘to hunt or catch the fox’ (to get drunk). There is even a connection between drunkenness and the crafty nature of the fox, based on a prose satire written by Thomas Nashe, an Elizabethan poet and playwright. In his Pierce Penniless, His supplication to the Divell