14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

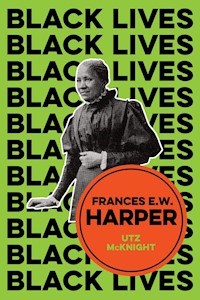

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Free Black woman, poet, novelist, essayist, speaker, and activist, Frances Watkins Harper was one of the nineteenth century's most important advocates of Abolitionism and female suffrage, and her pioneering work still has profound lessons for us today. In this new book, Utz McKnight shows how Harper's life and work inspired her contemporaries to imagine a better America. He seeks to recover her importance by examining not only her vision of the possibilities of Emancipation, but also her subsequent role in challenging Jim Crow. He argues that engaging with her ideas and writings is vital in understanding not only our historical inheritance, but also contemporary issues ranging from racial violence to the role of Christianity. This lucid book is essential reading not only for students of African American history, but also for all progressives interested in issues of race, politics, and society.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 503

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright

Preface

1 Frances Harper’s Poetic Journey

A life of consciences

Frances Harper in the 1820s and 1830s

Frances Harper in the 1840 and 1850s

African American print culture

Always free

A private life

Frances Harper in the 1860s and 1870s

Frances Harper in the 1880s, 1890s, and 1900s

2 Iola Leroy: Social Equality

The plot

Racial healing

Intimacy

Ways of being

The call to action

White equality

Conclusion

3 Trial and Triumph: The Public Demand for Equality

Responsibility and judgment

The plot

Race and public opinion

After slavery

Turning race inside out

Christianity

Conclusion

4 Sowing and Reaping: Personal Solutions and Conviction

Complicity

The plot

The vote

The personal is political

Women in private and in the public

Gender and race at home

Of money and fame

Conclusion

5 Minnie’s Sacrifice and the Poetic License

Politics

Minnie’s Sacrifice

The plot

The poetry of a people

Nation building

A Black faith

The power of prayer

The common struggle

6 Conclusion: Of Poems and Politics

Mourning

The reader: the call to conscience

Bibliography

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Series Page

Title Page

Copyright

Preface

Begin Reading

Bibliography

Index

End User License Agreement

Pages

ii

iii

iv

vi

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

Black Lives series

Elvira Basevich, W. E. B. Du Bois

Utz McKnight, Frances E. W. Harper

Frances E. W. Harper

A Call to Conscience

Utz McKnight

polity

Copyright © Utz McKnight 2021

The right of Utz McKnight to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2021 by Polity Press

Polity Press65 Bridge StreetCambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press101 Station LandingSuite 300Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-3555-2

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Names: McKnight, Utz Lars, author.Title: Frances E. W Harper : a call to conscience / Utz McKnight.Description: Cambridge, UK ; Medford, PA : Polity Press, 2020. | Series: Black lives | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “The first full account of a leading 19th century female writer and anti-slavery activist”-- Provided by publisher.Identifiers: LCCN 2020015772 (print) | LCCN 2020015773 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509535538 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509535545 (paperback) | ISBN 9781509535552 (epub)Subjects: LCSH: Harper, Frances Ellen Watkins, 1825-1911--Criticism and interpretation. | Harper, Frances Ellen Watkins, 1825-1911--Political and social views. | Social change in literature. | African Americans in literature. | Politics and literature--United States--History--19th century. | Antislavery movements--United States--History--19th century.Classification: LCC PS1799.H7 Z73 2020 (print) | LCC PS1799.H7 (ebook) | DDC 818/.309--dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015772LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015773

The publisher has used its best endeavors to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Preface

Why does the general public today know so little about the life and writing of Frances Harper? She accomplished a great deal in her lifetime, and was a leading voice for African Americans in several national movements over the course of several decades. An abolitionist, temperance organizer, and suffragist, Frances Harper was also the most important Black poet in the country until the 1890s. She published many books of verse, four novels, numerous essays, letters, and newspaper reports, and several short stories. Her poetry readings and speeches were always sought-after events, well attended by the public.

Two book-length monographs on her literary and professional work have been published in the last three decades. Melba Boyd’s Discarded Legacy (1994) and Michael Stancliff’s Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (2011) give readers a thorough overview of her career and creative work, if from different perspectives. Frances Smith Foster’s reader A Brighter Coming Day (1990) provides a handy resource that includes many of Harper’s recovered poems, novels, speeches, and letters. Most of her recovered work has been the subject of academic articles, and also longer book chapters, by some of the most influential academics in the field of African American history and literary studies.

Frances Harper was by any professional measure one of the most successful individuals in the last half of the nineteenth century. She didn’t, however, gain recognition by doing what was expected or easily achieved. As a Black woman, born free in the time of slavery, Harper sought above all to apply her creative talents to fighting for racial and gender equality in the US.

Frances Harper is at one level a formidable interlocutor. Her many poems, speeches, letters, short fiction, and novels make for a daunting engagement. There are some decisions that have to be made about the presentation and the argument about Frances Harper’s contribution to Black intellectual thought, as a historical figure and for us today. I have chosen to present her writing and aspects of her professional life as a cohesive argument about how she thought of politics, equality, and the challenges of democracy. There are many different approaches possible with the study of the writing of someone so prolific and talented, as well as someone who was actively organizing politically throughout her life.

Frances Harper lived in interesting times, during which, after two centuries, a Civil War brought about the end of slavery. She spent 40 years fighting for voting rights for women, falling short of this goal in her lifetime. She witnessed the creation of a new regime of racial terror in the US, the collapse of the hopes and dreams of a newly freed people, at a time when industry was advancing rapidly. She traveled extensively, met thousands of people over her life, and was an astute observer of her environment and the living conditions of the people around her.

Frances Harper comforted John Brown’s wife after the failed rebellion as he was waiting to be executed; she lectured alongside Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass; she was friends with Harriet Tubman; and she regularly had Ida B. Wells stay at her house in Philadelphia when she was traveling through. She was used to long hours on trains and coaches, and walking through the quarters of former slaves on plantations in Alabama and Georgia. She was raised in what was then the center of Black life in the US, Baltimore, Maryland, and so grew up surrounded by intense social activity. This is someone I would have loved to meet and talk politics with. Frances Harper was extremely talented and was always working on different projects of great importance and interest to many.

I have chosen to provide an overview of some of her writings, while ignoring the letters as private, and skipping some of the short pieces of fiction, and that comes at a cost. Frances Harper wrote and accomplished enough in her lifetime that no one series of poems, books, short stories, speeches, and letters can be thought to encapsulate her oeuvre. The closest we have to a comprehensive review of Frances Harper’s work is the extensive study done by Melba Boyd in Discarded Legacy. Frances Smith Foster has – in collecting many of the available written works of Frances Harper in one volume, A Brighter Coming Day – not only provided useful commentary, but also organized the work chronologically so that the reader can follow the arc of Frances Harper’s life in the written material. Stancliff, in his book, applies the work of Frances Harper to the study of rhetoric and pedagogy with superb results.

Acknowledging Frances Harper’s genius and the incredible scope of her work, the fact that there are many very good studies to draw from, including articles written on specific works by Harper, is encouraging. I want us to read Frances Harper, and to do so as a call to a democratic politics that requires that race and gender be central to our understanding of this society. Her work is compelling and demanding, and without the research and recovery work of several amazing academic historians it would not be possible to read it. Frances Harper’s works have not been adequately preserved, which in part accounts for her obscurity. For the last four decades, scholars have done the investigative work to find and restore her legacy to us.

I have chosen to use the name Frances Harper throughout to signal her authorship, even though this does interestingly coincide conceptually with the struggle that she experienced in her own life, where she wasn’t accorded sufficient professional respect as a speaker on behalf of the Abolition of slavery until she had been married. As Frances Watkins prior to her marriage, she published poems and was active in public gatherings as a speaker, and the brief years of her marriage were a time of relative retreat from public writing. After her husband’s death, the appellation “Harper” appended to her name allowed her the social cover afforded by the patriarchal tradition of the time. This distinction of social respectability, of having been married, in contrast to being an unmarried woman, was important in public, as a public speaker, and in the context of being a woman author of poetry and prose.

The reader should understand that there is a particular convention of names and naming, a politics of respectability with regard to women as authors, that remains accepted today, and that the social elements of this convention directly speak to a similar politics of race and gender that Frances Harper made the central part of her life’s work. Names are not innocent, but full of portent and history, and few authors have been more aware of this than Frances (Ellen Watkins) Harper. I use the name Frances Harper here throughout not to conceal or suture over this politics, but to suggest that it matters that when she could have returned to using her maiden name of Watkins, after her husband’s death, she did not; that, when she could choose, she kept the name of Harper, when as a child she could not choose anything but the name of Watkins. Harper was the family she chose.

It is through this representation of respectability, publicity, and personal ambition contained in what seems today marginal, even ephemeral, to a life of the writer and poet Frances Harper that we can begin to understand the challenge her work poses for us today. This was someone who – not only in her poetry and writing, but in her person, her speeches, and organizational activity – raised a challenge to the idea that Black women have not always been central to the development of the society. In this struggle against the social elision of Black women in society, Frances Harper is of course not unique. What she was able to do, however, was not only to overcome the social conventions of her time to publish, speak in public, and organize at the national level, but also to write about the problem of race and gender at a time when women couldn’t vote, and for the first decades of her life she was a free Black person in a society where the enslavement of Black people was the social norm.

Frances Harper wrote, lectured, and organized while being active at the heart of the Abolitionist Movement, the Temperance Movement, and the Suffragist Movement. She traveled in the South immediately after the Civil War, and sent what today would amount to newsworthy dispatches north from the frontlines of the aftermath of the War. Frances Harper was one of the architects of the modern Women’s Rights Movement, and she also was one of the first truly public intellectuals for Black Americans in the country. She spoke to and wrote for Black men and women at a time when the struggle to define the terms of Black life in America was both visceral and of immediate concern to everyone in the society.

It is important to understand that, though the sheer volume and contribution Frances Harper made to her public and the society during her lifetime are unappreciated today, certain pieces of her work have circulated widely. The claim in this book follows that of the researcher Frances Foster and others: that Frances Harper wasn’t ignored, but instead diminished in importance. There is a particular politics, therefore, not simply of recovery, but of discovery, of developing a new description of the place of African Americans in this society, in working with the writing of Frances Harper. This book contributes to existing scholarship that seeks to make one of the most important thinkers and writers of the nineteenth century available to a wider audience. In doing so, it also provides a description of another America, a new society that we should aspire to become – one that acknowledges and understands the contribution of all members of the society to how we think of this nation.

The structure of the book is designed with, first, a biographical chapter. Chapter 2 discusses the novel Iola Leroy, in order to frame the oeuvre of Frances Harper and to provide an understanding of the themes of her earlier writings. Next, chapter 3 addresses Trial and Triumph, and then chapter 4Sowing and Reaping and “The Two Offers.” Chapter 5 considers Minnie’s Sacrifice and the poetry of Frances Harper. Chapter 6 concludes the book with a discussion of her poetry.

Three considerations guide this approach to her work. The first and most important is that readers encounter the familiar first. If they have read anything by Frances Harper, it is usually Iola Leroy, and if not, it was one of the most popular novels in the last decade of the nineteenth century and should occupy pride of place for that reason. Second, I want the reader to get an understanding of the sophistication that determined the choices made by Frances Harper of genre, plot, and character in the novel, and to appreciate the overwhelming task with which she was faced in trying to establish a narrative of hope and progress for Black people in the 1890s in the US. The book was published the same year as Ida B. Wells’ study of lynching, Southern Horrors.

Third, the reader today knows that what Frances Harper tries to do in the novel with regard to her intended audience fails. I want the reader to understand that this is why the work of Frances Harper has been neglected until recently. In Iola Leroy, Frances Harper tried to gather the strands of a decaying set of political possibilities that were offered with the freeing of the slaves at the end of the Civil War. She tries to bind everyone up together. It is because she does this in Iola Leroy that we have in the novel her mature thinking about the politics of race as a societal idea. In the novel, she provides for the reader a vision of potential societal change, of what counts for political progress as a nation. It is here that she develops for us a radical egalitarian vision.

Chapter 3 takes up the novel Trial and Triumph to provide the reader with Frances Harper’s perspective on community. What is required of the idea of equality to form a progressive and thriving community? Given the forces threatening to dissolve the relationships that the freed people had managed to develop after the War, what should the community do to resist its dissolution? In the novel, Frances Harper discusses the criteria for social community relations, how desire, avarice, fame, and modesty can be acknowledged so that the community can meet the challenges that it faces from a reconsolidating White authority in the society. The novel discusses many of the same problems of race and gender as we have today, and Frances Harper demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of the need for a description of equality that is always aspirational, external to the current conditions in the existing community.

In chapter 4, the reader is asked to think with Frances Harper about the demand for individual perfectionism and the problem of moral suasion in the society. The discussion considers the idea of individual, personal politics in the novel Sowing and Reaping, and includes also a study of the short story “The Two Offers.” Frances Harper had the idea that the personal realizes concrete results in the community – a politics that then realizes change in the larger social world. She felt that, from personal decisions about morality and social practices, the necessary political changes could occur that would protect the community. The chapter addresses the struggle by the individual to determine how to positively contribute to the needs of the community.

The second through fourth chapters develop Frances Harper’s description of how social change occurs and what is at stake in the period after the War for the society. Focusing on societal, community, and personal perspectives in her work allows the reader to grasp the complexity of her writing and activism. In chapter 5, the reader encounters the earliest of Frances Harper’s novels in Minnie’s Sacrifice; and the idea of what Frances Harper means by politics, and what her goals were in the work, are considered. The reader is brought into conversation extensively with her poetry for the first time. In doing this, we have come full circle to the reading of Iola Leroy in chapter 2. We can see the genesis of Iola Leroy in our study of Minnie’s Sacrifice and the poems, and can ask the question of how we today should reconsider the challenges Frances Harper posed to her audience in the last half of the nineteenth century. In chapter 6, the conclusion, the conversation with the poems continues. The reader is asked to think with Harper about what is required to achieve progress toward racial and gender equality in the society.

1Frances Harper’s Poetic Journey

A life of consciences

We are always writing for the present, for those who share the concerns and anxieties of our lives. But, of course, we can’t know how what we say and do today is measured by those who come after us, in spite of our desire to inhabit the thoughts and concerns of those who follow. Frances Harper – author, abolitionist, orator, political organizer, temperance activist, suffragist, mother, Black, American, woman – she dedicated her life to the politics of racial and gender justice.

Frances Harper was born in 1825 and lived an incredible life, sharing her ideas and her creativity with an American public until her death in 1911. She grew up a free Black person in a society where the majority of Black people were enslaved. The writer of the first short story published by an African American woman, Frances Harper also produced Iola Leroy, one of the most popular fiction novels in the US of the latter half of the nineteenth century. She was an accomplished and popular poet, and was able to make a living on the sale of her poetry at a time when it was not possible for a Black person to find a position at a university. An important orator and organizer for the Abolitionist Movement, the Temperance Movement, and the Suffragist Movement, Frances Harper was an activist – what we today call a public intellectual – with the tenacity and skill to remain at the center of the sweeping political changes that occurred in her lifetime. She was frequently published in the leading African American newspapers and magazines, contributing her ideas to a wide public in the society (Peterson, 1997).

What Harper couldn’t know is that, by the latter part of the twentieth century, her own contributions would be largely obscured by the very forces of racism and sexism that she fought against all her life (Foster, 1990). Each discovery today of the wealth of contributions made historically by Black women in the society is a mandate to again center these voices integral to the American democratic project, who, because of the politics of their time, were obscured or have subsequently had their contributions largely erased. We can only wonder how much of what was achieved by those living before us is unrecoverable; how much of what was accomplished has been erased by disfavor, disinterest, simple neglect, and the prejudices of popular opinion. Our history is derived from the imagination of those who would silence and vilify certain persons, groups, and causes. What ideas and work remain available from our past? What should we think today in a time when racial and gender inequality still remain definitive of American society?

What we do know is that, until the work of Black feminist researchers in the last four decades, much of the writing of Frances Harper was unavailable and thought lost. It is only through the work of these scholars, the diligent work of recovery and preservation, that we now have access, as well as to her popular novel Iola Leroy, to Harper’s three serialized novels, the work Fancy Sketches, many of her speeches, and the majority of her poetry. We owe a great debt to this research movement, by Black women working as established scholars, independent researchers, librarians, and activists. This dedication to recovering a Black past before the nadir in the late 1880s, and the decades of terror that described the time of lynching and Jim Crow, asks us as readers of Frances Harper’s work to question how we consider race and the contribution of Black people today in this society.

Even if the proximate causes have changed, the general social concerns that occupied Frances Harper are shared by us today. She can serve as an inspiration for both creative writing and political engagement. She demonstrates what was possible to do as an individual in a society where Black community members were enslaved and where women were not able to vote. What would it mean for us to live alongside those who remind us of the terrible oppression possible for us as well, to interact with those who share the burden of social descriptions of racial inferiority, even as our political status differentiates us? We know.

Today more Black people are in prison than were enslaved in 1825, and one out of three Black male adults will be incarcerated at some point in their lives. With large numbers of African Americans living in poverty, and a perception of racial inferiority that persists, with significant pay differentials between men and women, and #MeToo a necessity, the words of and life led by Harper provide encouragement and an example of how we might also thrive. The timeline for Harper’s life covers not only the last half of the nineteenth century, when the new nation sought to define its major institutions, but also the last decades of the centuries-long enslavement of Black people, the Civil War, and Reconstruction. She was present as the Western US opened up to settlement, and in the period of national development that saw rapid industrial growth, and then the portion of the late nineteenth century that, because of the establishment of Jim Crow laws and lynching, many consider the nadir of the free African American experience in the US.

Frances Harper in the 1820s and 1830s

Born in 1825, in Baltimore, Maryland, Frances Harper was orphaned at 3 years of age and went to live with her uncle and aunt, William and Henrietta Watkins. The family had a library, and as a child Frances was, at a young age, given access to books and taught to read and write. This encouragement was to be her fortune, and words and their value would become her lifelong passion. In Baltimore, where the family was living, the social relationships of the family gave Frances conversational exposure to people with an interest in the major political causes of the day. Her uncle William Watkins was an abolitionist and public speaker, someone with social standing in the community of people, made up of free Blacks and Whites, advocating for social causes and racial equality. William Lloyd Garrison and many other activists were regular guests at the Watkins household.

Harper’s upbringing among those who were were active in organizing against slavery and other social problems not only taught her the value of political activism but also provided her with an understanding of the importance of education and writing as tools to address social ills. The public critic – the person who would address an audience in speaking halls, living rooms, and in formal gatherings to advocate for changes in the society – was a fixture in the everyday lives of the inhabitants of the young nation. The first decade after Frances Harper’s birth saw the publication of David Walker’s Appeal, the public work of Maria Stewart in Boston, and Nat Turner’s Rebellion.

In Harper’s day, there were established organizations that sought various types of reforms and social change in the society at large. And in Baltimore, where she grew up, free Blacks and Whites had long been able to establish a public audience ready to discuss a wide range of social causes and issues, through printing newspapers, adverts, and lectures (Foster, 1990). This public forum, a social space within which to publicly make statements and admonish fellow inhabitants and the government, was active throughout the mid-Atlantic seaboard and the East Coast in the 1820s. While, just as today, it was not clear how discussions in this public arena determined the definition of government interests, there is no question that the public intellectual in the nineteenth century had an importance beyond the imperatives of electoral politics. Much of this has to do with the place of this sort of public discourse in local politics – how independent town, city, county, and state politics are from the supervision of the federal government in the US. Electoral parties in the US are not an end in themselves, for a public is always engaged in discussion about the merits of a law, a policy, or the conditions in which local people live.

Unlike other Black women who became well-known public figures during her lifetime, Frances Harper did not have the financial means to remain at home throughout her childhood (Foster, 1990). Having established a school in 1820 – the Watkins Academy – her uncle William Watkins was able to provide the young Frances Harper with the vocational training necessary to succeed at those occupations conventionally available to her as a free Black woman. It was this training that allowed her to work, as a teenager, as a young servant in the household of a White family, and, eventually, to be the first woman hired as a faculty member to teach sewing at Union Seminary in 1850. When she later moved to Ohio with her husband to run a dairy farm and help raise their children, this practical experience as a servant was important, and necessary when she was shortly thereafter widowed and working to keep the farm. Frances Harper was raised with the best training available for someone Black who had no access to independent sources of income. This is a condition that most African Americans are too familiar with today, with a negative savings rate and few assets being the norm for too many families. She had to survive by the education that she received, opportunity, hard work, and the trust and assistance of those around her. This was a free Black person’s life in the 1820s and 1830s, and is true today for us as well.

Harper’s work as a servant paralleled the types of work done by those who were enslaved, but with the glaring distinction of being free – free to make use of her own life and time as she would, each day. As a servant, however, she came face to face with the consequences of a politics of race in the society whereby some Black people who worked were free, and some slaves. This experience undoubtedly transformed her thinking about how race defined the lives of Black people in America.

In the 1820s and 1830s, when Frances Harper was a child, the state of Maryland reflected many of the major forces for change in the new nation. Baltimore and surrounding areas were places where free Blacks could live alongside slaves in large numbers – enough to make the differences in status between Black people an explicit public issue that Whites sought to address. Whites did not generally suggest enslaving those who were free, but instead sought to reduce the number of free Blacks who lived in the state (Fields, 1985). The uneven economic development between the state’s northern counties and southern counties was a source of great tension among politicians. The importance of slaveholding for agriculture and economic development that prevailed elsewhere in the South was not evident in Baltimore, even if true in the southern parts of the state. The importance of Baltimore as a growing industrial center on the mid-Atlantic seaboard meant it was a center for the political currents that were sweeping the young nation. For Frances Harper, growing up in Baltimore meant that she was regularly exposed to the social conditions of slavery, as well as given an insight into the value of schooling and literacy for effecting social change (Parker, 2010, p. 102).

Think for a moment of what Frances Harper’s attendance at the Academy run by her uncle must have signaled for the slaves working around her, slaves who often were prohibited by their Masters from learning to read and unable to write. It is important not to make a false equivalence between what slavery and being free meant for Black people at the time. Slavery remains a terrible wound in our history today, but we don’t need to think of Black people as always available to its constraints as a condition of living in the society, or as the limit to our political ambition. The necessary national conversation that we have today about reparations and reconciling the effects of slavery generations later should not prevent a discussion of how free and slave Black people lived alongside one another. What it meant to be Black at the time, and after the Civil War, should include such an understanding of the complexity of Black life.

Frances Harper’s was a singular political awareness, if we consider the situation for a moment: to be free and yet to be exposed as a young child to those who were not; to be socially conscious of the aspiration toward racial equality derived from the attitudes and behaviors of those Whites who frequented the Watkins’ home; to know that many Black people discussed the plight of those enslaved even as they wrote, spoke publicly, and organized for the welfare of those who had run away. She also came into constant contact with White slave owners, and those who perceived her free status as an impediment to her exploitation, even as they dismissed her capacity for constraining their desires with regard to their own slaves.

What would a White stranger have represented socially, politically, for Frances Harper? What would a slave have been for a young Frances Harper, if not a person to be pitied, and also an immediate existential threat, a literal symbol of the precarious nature of her own status in Baltimore (Fields, 1985, pp. 39, 79)? In the 1820s and 1830s, when the kidnapping of free Blacks to be sold as slaves further south was common, how did Frances Harper determine the motives and interests of the adults, White and Black, around her? I write this to have us consider how race was a factor in the young Frances’ life, in contrast to how it is in our own lives. How would others have perceived this young woman, who was not only courageous and literate, but also independent? And though her situation with regard to opportunities for an education was unique, she herself, as a young free Black girl child, was not unique in Baltimore, or in the society as a whole.

How has our awareness of race changed, and what remains accessible to us of what she must have known? Answering this question requires a degree of reflective sophistication about the influence of race on our lives – an awareness that Frances Harper demonstrates throughout her work. It would be a rare person today who would have her degree of insight and courage. Thus, it is important to remember, when we read her poetry and books, how few of us have the same perspicuity, the determination that was required – when there were slaves present, and when women were unable to vote and were expected to be silent in most public fora – to confront the description of her own racial subordination in her public writing (Stancliff, 2011).

Today, when so many people write and publish works on race and society, it is simply too easy to remain within a narrative that sees progress in the fact that Black people can publish and find an audience for their work. Reducing the achievements of those like Frances Harper to a simple content analysis, or a discussion of literary form, reduces the achievements of those, like her, who succeeded at a time when there were substantial barriers to publishing and making a career as a public speaker and poet. Leveling the field of production in this way reduces the importance of the work that others have done to change how the society addresses race as a problem, and we tend to ignore the organizational and professional effort that this success took – how it was also a tremendous step in our progress toward the ideal of racial equality. To what extent is it possible to make sense of the types of commitments that are evident in the life of Frances Harper such that she would become the most successful Black poet of the mid nineteenth century, a writer of four novels – one of which was a bestseller – a public speaker, an essayist, and a leading organizer of social movements in the United States for almost 50 years?

In her letters, it is clear that Frances Harper led a life whose main ambition was to correct the racial and gender injustices that she perceived in the world around her. The activist and literary world in which she lived, as well as how she was raised when young, fostered an awareness of a politics of representation in her own person as a Black woman writer and social critic. This commitment to what we today call civil rights is ever present in her writing, her speeches, and her advocacy. I want to suggest that it is only now, with our complex theories that address the conjoining of the critical politics of race, gender, and sexuality, that there exists a public readership that can respect and understand how a Black woman could be one of the most important writers, poets, and activists of the last 50 years of the nineteenth century. Her story now can be brought to our attention as a difference of perspective that matters, her work given a place as an important component in a developing narrative of a diverse American democratic polity.

It is not a coincidence that, though Frances Harper was prolific and successful as a writer, her contribution to our understanding of the period in the nation’s history has until very recently been obscured. Today we largely accept a description of the period of US history from 1850 to 1900 that has emphasized the story of the slave struggling for freedom, those valiant individuals who freed themselves through personal ambition and great adversity, and the successful heroic work of White people to emancipate the slaves who were unable to escape to freedom – the benighted and beleaguered, the self-emancipated, the savior and humanitarian. This is too easy a combination of roles to be true, to be the only description of what was possible for those who lived in the period. There are other narrative voices. Today, we increasingly include the claims of how slaves and free Blacks fought alongside their White compatriots for freedom during the Civil War, and how slaves were forced to fight in support of Confederacy.

But a story about American democracy that seeks to simply reconcile the fact of enslavement for Blacks with the ownership of other human beings by Whites is too easy and inaccurate, and accepts a problematic convention for slavery as a condition for some in the society. Thus, we have Harriet Tubman, who was a friend of Frances Harper, as well as Frederick Douglass, who worked often alongside Frances Harper over the years, in the Abolitionist Movement and later in the fight for voting rights for Black people and women. These two are thought to represent today in the collective imagination a necessary and particular depiction of what it meant to be Black and American in that time in US history.

We ask the questions of the past that provide the answers we need in our own lives. The runaway slave, the slave who confronts and defeats the ambition of mastery by the owner, the slave who goes on to free others, who publishes and speaks in public about their successful emancipation, make us think about what it means to live in a society where slavery was possible. Both those whose ancestors owned slaves and those whose ancestors were enslaved can supposedly find a form of reconciliation, a foundation for going forward together, if the history of slavery is viewed as a mistake, reproduced over many generations – one corrected through righteous struggle by those whose morality and personal conviction overcame greed. Sacrifice and suffering finally came together for the cause of freedom: to free the benighted Black slave, to educate and lift up those least fortunate.

Frances Harper represents a different voice from that of Harriet Tubman or Frederick Douglass, as well as that of Sojourner Truth or William Wells Brown. Instead of seeking to establish her equality to a White person who is not a Master, as a concession to a personal emancipation, Frances Harper embodies in her writing and public speaking the always free Black person who also represents the democratic aspirations of the society. To constantly measure racial equality with a claim to having once been enslaved – as being less than human perhaps in the eyes of some – retains in the new conception of race after slavery the condition, the possibility, of an enslavement to come. Such an argument suggests that the baseline of the Black experience is always slavery, and not a freedom that is suborned or taken away. This difference in perspective matters today, as we seek a description of how racism thrives in spite of our effort to create conditions of equality socially, economically, and politically.

Imagine instead if a person had always been free, if someone Black in America had never been a slave. Should we then make the story of slavery their definition, rather than accept that for many Black people in the US slavery and freedom were more complicated, requiring a description of racial equality beyond that of asking Whites for justice in the form of allowing Black people to be free? The end of legal slavery occurred concurrently with the argument about what constraints could exist for free Black equality in the society, a conversation centuries old, about the definition of political equality between racial groups in the society. Frances Harper is an important voice in this tradition of exploring the definition of racial equality within the Black community – someone who left a legacy of published work for us to consider.

The kidnapping of free Black people and their sale into slavery caused a furor in the society in the decades leading up to the Civil War not solely because the sale of Black people was thought by many to be morally wrong, but because it suggested that all Black people were potentially slaves, in ways that had not previously been true in the US. This idea of slavery as a natural state of Black life in the US not only is incorrect historically, but also allows for an erroneous description of the racial justice to be achieved today. It is very important to understand the contribution of Frances Harper to how we think of race today, in terms of her being a free Black woman writing during the last two decades of legal slavery, and then for several decades after the Civil War. There was no one else in the period, no other free Black writer or poet, who addressed the problem of both race and gender, and what these ideas meant for the society, with such success. Frances Harper is singular, unique, and I want to suggest her work is central to a consideration of how we should think of race and gender in the US from the 1840s to the 1890s, and therefore also how we describe a critical race and gender politics in the US today.

Frances Harper’s work disturbs a desire to return today to a conversation about what race requires as a supposedly natural condition – the desire to engage in this as a question, rather than to reject its assumptions as fundamentally flawed. It is important to understand how important this counter-argument to slavery was in her lifetime, and how in the 1840s and throughout her life she wrote about the intersectional politics of race and gender as an aspiration of democratic society. Her life and work represents a very different description of racial reconciliation for the society than is often offered when thinking only about the concerns of the White male slave owner, the permission given through a definition of Whiteness for the ownership of human beings, over many generations in the society. That she spent her entire adult life writing, speaking, and campaigning on behalf of racial and gender justice is a fact that should add weight to our assessment of her legacy, and should make us think twice about the current tradition of reducing her contribution to American letters and society in her lifetime to a few short poems and one major novel, Iola Leroy.

Frances Harper in the 1840 and 1850s

If we take the newly rediscovered volume of verse, Forest Leaves, as having been published sometime between 1846 and 1849 (Ortner, 2015), Frances Harper was between 21 and 24 when she published her first volume of verse. She no doubt wrote poetry before this, but in the extant letters from the period there is evidence of some reluctance on the part of publishers to publish the poems. Her childhood education at the Academy and experience as a servant in a household with an extensive library that she was given permission to peruse in her free time, and the exposure to poetry readings and public speeches in the abolitionist social community of which her uncle and aunt were a part, provided the opportunity for Frances Harper to develop her craft. In this, but for the material differences in our lives today from hers, Frances Harper had what many today would think of as those influences necessary to create a poetic muse.

Her uncle William had been at the center of the development of the Abolitionist Movement in Baltimore for decades, and was an active contributor to the publishing of writings in support of the Movement. His house was a frequent location for meetings with other central figures of the growing Abolitionist Movement, such as Willian Lloyd Garrison. One of William’s sons, a cousin of Frances Harper, was also involved in the Abolitionist Movement and a public speaker on this issue. He would later facilitate her introduction to abolitionists in the Northeast (Washington, 2015). But another influence on the life of the young Frances Harper was the work of women writers and poets, and public speakers in the Abolitionist Movement, such as Jarena Lee, Zilpha Elaw, and Elizabeth Margaret Chandler (Washington, 2015, p. 69). Even as a young child, she was brought into contact with the work and persons of women who were able to publicly declare their ideas about slavery, racism, and gender.

This publicity was at odds with the prevailing gender social norms whereby women were expected to be silent in public gatherings where men were present, and not engage in public speaking to an audience comprised of both men and women. This early exposure to women writers, poets, and speakers was definitely important to the young Frances Harper’s sense of what was possible. She would go on to be only one of several Black women to speak regularly as part of the Abolitionist Movement (Peterson, 1995).

African American print culture

It was from Sojourner Truth that Frances Harper saw firsthand the difficulty of making a living as a public speaker. To raise sufficient money for her travels and sustenance while on the speaking circuit, Truth would sell small commemorative items related to herself and her story at her talks. Truth’s image on sale, in the pamphlets, was for everyone present a natural extension of the tradition of printing and public newspapers in the free African American community throughout the Northeast at the time. Instead of ignoring the growth of print culture in the African American community, we should consider how important this must have been for Harper, as an aspiring poet and writer – someone who sought to reach an audience with her written word (Peterson, 1995, pp. 310–12).

The Liberator, a newspaper published first in the 1830s by Garrison, was constantly seeking submissions from African Americans, for example, as was The Colored American. Once Douglass started publishing the newspaper The North Star in 1847, Harper and other aspiring African American writers were given a ready forum in it. Frederick Douglass’ Paper and Douglass’ Monthly, his other two newspaper publications, also published their work (McHenry, 2002, p. 116; Washington, 2015, pp. 61–6). While certainly there was an eager White American readership for this work, there was also an extensive African American audience for these newspapers and for literary magazine content. African American literary societies had been an important mainstay of the free African American community since their inception, and before the founding of the new nation. The newspapers that circulated within the free African American communities emphasized the importance of reading and education as a means of moral and political progress. It was in Freedom’s Journal, published from 1827 to 1829, that African American literary societies and their participants, such as David Walker and Maria Stewart, were able to find a larger audience for their writings. In 1837, The Colored American began publishing work dedicated to the audiences from these literary societies (McHenry, 2002, p. 102).

Always free

It is very important today to understand what the erasure in our collective memory of the presence of a larger, engaged African American reading public prior to the Civil War means for us (McHenry, 2002, p. 137). This erasure serves, in this period, to elevate the struggle for Emancipation and the plight of the slave as a condition of African American life, over the reality of a free Black population that was considered already literate, and engaged in the emancipation of their brethren in bondage. And it makes it too easy to suggest that education and reading have not always been an element of African American life. It allows us to think, therefore, that the problem of race today is simply that suggested by Booker T. Washington toward the end of Harper’s life at the turn of the nineteenth century, to cultivate well-meaning charitable White interests to advance the education of the race. It is not a coincidence that the two literary Black women figures who were well known prior to the Civil War, Maria Stewart and Frances Harper, have had their contribution to our development of ideas about race and society eclipsed by the images of Black women who could not write, such as Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman (Connor, 1994, pp. 74–5; Painter, 1996).

This traditional narrative of erasure truncates the true relationship between Black people and slavery in the US, ignoring that the nation always also contained a free population and that the idea of enslavement is therefore artificial and wrong. This narrative was only true for those seeking to propagate a politics of racial subordination that seeks to reconcile the fact of slavery historically with the need to claim that Black people are always unequal. We can see the development of this racist polemics in how Harper responded to the history of the aftermath of the Civil War in her book Iola Leroy, published in 1892.

Prior to the Civil War, however, Black people had already achieved equality in their literary pursuits – if not materially – with Whites, alongside the presence of slaves in the society. Frances Harper, and all other free African Americans in the society in the 1840 and 1850s, were well acquainted with the importance of literacy and print culture. Periodicals and newspapers formed an important part of the sense of community, as these allowed for news, public debates, and literary works published by Black people to be available to the larger Black population (Peterson, 1995, p. 310).

In the 1850s, the newspapers the Christian Recorder and the Weekly Anglo-African were published, and magazines dedicated to African American literary works began to be published: the Repository of Religion and Literature, and of Science and Art and the Anglo-African Magazine. It was in the first issue of the Anglo-African Magazine in 1859 that Frances Harper began serializing her short story “The Two Offers,” and Martin Delany began serializing his novel Blake; or, the Huts of America (McHenry, 2002, p. 131). And the Christian Recorder was where Frances Harper would publish three novels serially from 1868 to 1888, in addition to the short piece Fancy Sketches (Peterson, 1995, pp. 307–8; Robbins, 2004, p. 179).

In the 1840s and 1850s, when Frances Harper was beginning to find her poetic and literary voice, there was a public ready for her, an audience of African Americans and White Americans willing to carry around her small books and portable newspapers and magazines for further distribution. There was a public that would meet in salons and dining rooms, in literary circles, and read and discuss her poems. It was to this public that Frances Harper became visible in her early twenties with her first book of poetry Forest Leaves, and it is this that partially explains the phenomenal publishing success of her book Poems on Miscellaneous Subjects in 1854.

This book of poems would go on to be reprinted 5 times over the next 17 years, and over 10,000 copies were printed. As Michael Bennett points out when comparing the popularity, and therefore public importance, of Frances Harper to that of Walt Whitman at the time, fewer than 100 copies of Leaves of Grass were sold when it was published in 1855. There was no interest in Whitman reading his poetry in public akin to that for Harper. She was, in contrast to Whitman, “the poet of democracy” (Bennett, 2005, p. 48).

In the 1850s, Frances Harper was considered an important poet in the society – one whose poems spoke to the immediate social and political concerns of the population. By the time of the publication of “The Two Offers,” the first published short story by an African American woman, Frances Harper was a well-known and important literary figure, not only in African American society, but in abolitionist circles and the White literate public. By the late 1850s, Frances Harper was a very popular public speaker, and sold her books of poetry to successfully support herself, as Sojourner Truth did with her images.

The question we have to ask ourselves today is how committed we are to the idea of a description of Black women as available to caricature and stereotype, as unequal partners in the democratic polity, meaning that we resist understanding the place of Frances Harper and other Black literary women in developing a response to the challenges of race in the society (Harris, 1997, p. 93). By the 1850s, Frances Harper had begun to establish a literary reputation, not as a former slave but as a quintessential American poet, someone whose writing addressed the major fault lines that existed in the fledgling democratic society. As someone who had always been free, Harper could not be looked upon by White Americans with that particular mix of charity and condescension, the disdain due to having been perceived as less than or differently human, that was reserved for the former slave.

That Frances Harper became a poet and writer, a public speaker, a national organizer should be understood for what it represents for us today, in our perspective on the history of race in America. It is not slavery that defines Black life today, but the need to equate Black people with slavery, with a capacity to be enslaved, unlike White people. Eschewing the idea of slavery as the description of a possible Black life, Frances Harper did not see herself as categorically less than human.

This perspective should not immediately be contrasted with a description that obviates or erases the terrors of slavery, which remained the most important social and political problem in US society in the 1840s and 1850s. Instead, a consideration of Frances Harper’s life should disturb the equation we have today of racial uplift with the convergence of White largesse and moral clarity that we often use to explain Black life after the prohibition of slavery. Not all Black people required an education by Whites in the obligations of citizenship and equality, and White people in the 1840s and 1850s understood this, if they were not too prejudiced to even entertain the fact of a free Black reading and literary public.

A private life

The Baltimore where Frances Harper was raised in the 1840s was rife with racial tensions, and the economy was growing rapidly due to the trade in cotton and industrialization (Fields, 1985). This meant that ideas about racial equality, and ideas of economic and political development that were of importance elsewhere in the country, were of great interest locally. The Abolitionist Movement had been gathering more adherents throughout the 1830s and into the 1840s with increased publicity, and William Lloyd Garrison and others were frequent visitors to Baltimore. The Movement as a political and therefore public force, in newspapers and magazines, in lectures and speeches, was an established part of Baltimore public culture. Frederick Douglass, who had been enslaved in Maryland, published his first autobiography in 1845, and became a celebrity public presence amongst those in the Movement. He was only seven years older than Frances Harper, and therefore a social contemporary, unlike Sojourner Truth, who was born in 1797.

Frances Harper, because of her family’s involvement in the Movement, would have had contact with both noted Black abolitionists by the 1840s. She would work extensively with both in the decades to come. Frances Harper would also come to work with Harriet Tubman from the 1850s, from whom she was only three years apart in age. It is important to give readers a sense of the activist environment that surrounded Frances Harper in her teen years and twenties, as she began to form her ambition for a vocation beyond that traditionally available to her as servant and housewife.

I want the reader to resist the compression of generations, particularly when considering the life of someone such as Frances Harper, whose work reflected the different political forces at work in different decades. It does matter that, when Frances Harper was a young child, the organization of anti-slavery efforts in Boston led to the publication of David Walker’s Appeal