Table of Contents

CONTENT

Foreword

Dedication

1. The "discovery of America" (1492) - lightning and shock

2. The three deadly sins of the early modern period (16th/17th century)

3. Fleeing to the colonies from war and absolutism in Europe

4 The dawn of Enlightenment

5 The American War of Independence (from 1776/1787)

6 The Great French Revolution and its consequences (1789 ff.)

7. revolution and reaction in Europe: 1815-1848

8 Germany's failure with "its Paulskirche" in 1848/49

9 Alexander v. Humboldt: "Cosmos" and cosmopolitanism in the 19th century.

10 The War of Secession (USA) and European imperialism

11 USA: From the Monroe Doctrine to the "Big Stick" (19th century)

12 USA/Europe: At the beginning of World War 1

13 The gradual abandonment of US neutrality (1914-1918)

14 Decolonization/fascism: interwar period 1918-45

15 USA: A belated world power before and during World War II

16 Cold War in the nuclear age: West versus East (1945-1990)

17 Revolutionary end to the bloody 20th century

18 "The end of history?" With terror, migration and climate catastrophe (20th/21st century)?

19 The German path to the West (Basic Law, reunification, EU)

20 "Germany" within the framework of the EU after 1990 and in the 21st century

21 Ukraine's war of liberation - traction for Western values?

22 USA - EU: Closeness or distance in the 21st century?

Bibliography

IMPRINT

CONTENT

1. The "discovery of America" (1492) - lightning and shock

2. The three deadly sins of the early modern period (16th/17th century)

3. Fleeing to the colonies from war and absolutism in Europe

4 The dawn of Enlightenment

5 The American War of Independence (from 1776/1787)

6 The Great French Revolution and its consequences (1789 ff.)

7. Revolution and reaction in Europe: 1815-1848

8 Germany's failure with "its Paulskirche" in 1848/49

9 Alexander v. Humboldt: "Cosmos" and cosmopolitanism in the 19th century.

10 The War of Secession (USA) and European imperialism

11 USA: From the Monroe Doctrine to the "Big Stick" (19th century)

12. USA/Europe: At the beginning of World War 1

13. The gradual abandonment of US neutrality (1914-1918)

14. Decolonization/fascism: interwar period 1918-45

15 USA: A belated world power before and during World War II

16 Cold War in the nuclear age: West versus East (1945-1990)

17 Revolutionary end to the bloody 20th century

18 "The end of history?" With terror, migration and climate catastrophe (20th/21st century)?

19 The German path to the West (Basic Law, reunification, EU)

20 "Germany" within the framework of the EU after 1990 and in the 21st century

21 Ukraine's war of liberation - traction for Western values?

22 USA - EU: Closeness or distance in the 21st century?

Foreword

The USA and Germany have long demonstrated their unity against Putin by delivering arms jointly to Ukraine. Within the EU and NATO, both countries are close allies against a neo-imperialist Russia and in defense of Western values. Nevertheless, there are still anti-American voices ("anti-Americanism") or anti-European sentiments ("anti-Europeanism") on both sides of the Atlantic.

It is clear that the that the causes of this "dispute between relatives" go back to the beginning of the modern era (Columbus). In Germany, it took almost 400 years before the "United States of America", which was already over a hundred years old, was finally perceived and respected as a serious, republican "nation" with a democratic "liberty". By this point, it was already attracting millions of emigrants from Europe. This perception continued until the end of the First World War. As a "belated nation", the Germans first "missed" the European Enlightenment, then the founding of the USA and the French Revolution in the 18th century by means of frequently used aberrations and "special paths". They then struggled to achieve the longed-for "national unity" in the Bismarck state against Napoleon and the "Paulskirche's own constitution". However, this success was then immediately squandered again in two world wars: with Wilhelminism, colonialism, imperialism and finally - almost to the point of ruin - through Hitlerism.

It was only in 1949, with our Basic Law, that we finally achieved a parliamentary democracy. This democracy embraced the core values of the Enlightenment, including separation of powers, the constitution, the constitutional state, the republic, equal rights and the dignity of man. This achievement was made possible with the support of the victorious Western powers, particularly the United States, whose constitution also emphasized "Liberty". We incorporated the important and humanitarian values and experiences of our "Paulskirche" of 1848/49 and the "Weimar Republic" (1918-1933) into our "Basic Law" (in the equivalent rank of a constitution).After the Second World War, the division of Germany (and Berlin) into West and East, and the emergence of the Cold War (with a constant threat of a third world war with global nuclear death) between the two democratic and Soviet victors over Hitler, made it impossible for humanity, not just the Germans, to have a secure sense of peace for a long time. It is clear that the decade between 1990 and 2000 was deceptive. The so-called 'end of history' and 'eternal victory' of democracy were illusions. The 'path to the West' (Prof. H. A. Winkler), which West Germany had only firmly taken from 1949 onwards, was only just possible (after 1990/91) for the East-Central European states of Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and parts of the Balkans - in a voluntary, independent and democratic decision.

Putin has made it clear that the path to the community of values of Western European enlightenment is now significantly more difficult. Nevertheless, Finland and Sweden have already courageously moved forward. Ukraine will follow suit.

Erhard Brüchert

Dedication

On the 300th birthday of:

Immanuel Kant - born in Königsberg in 1724

And for my

Former pupils

and my grandchildren today:

Marie (17), Tom (16), Tammo (14)

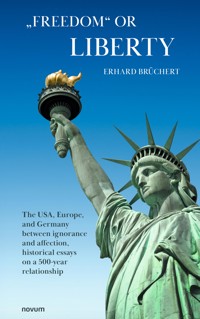

The cover photo:

Head of the "Statue of Liberty" - Neoclassical colossal statue on "Liberty Island" in front of New York harbor. Dedicated in October 1886 as a gift from France to the USA. Designed by Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, built by Gustave Eiffel - creator of the Eiffel Tower in Paris.

1. The "discovery of America" (1492) - lightning and shock

The daring but unfortunately lazy or even illiterate Vikings are known to have discovered the North American continent around the year 1000 and set foot on it from Europe for the first time. But they failed to inform the European "Occident" of this. They simply had no desire or time to acquire the Latin language as the great "lingua franca" during their numerous raids and sailing trips across rivers and seas in Europe. After just one or two hundred years, they also lost all interest in their settlements in Newfoundland and Hudson Bay. This was possibly also due to massive changes in the climate, as we are seeing again today in the third millennium AD. AD. But back then, it was getting colder, which we lack today. The Vikings were not going to sail to what would later become "America" in their small but seaworthy and fast dragon boats.-

Five hundred years later, in 1492, the Italian captain in Castilian-Spanish service, Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), reached the island of San Salvador from Genoa, , i.e. towards the end of the Middle Ages. Initially, his travels were confined to the Cuban and Caribbean regions, with his subsequent expeditions leading him to the American coastline.

Germanic National Museum Nuremberg

Christopher Columbus (1451-1506)

Columbus was far from satisfied with this turn of events, as his ultimate goal was to reach India, which had just been revealed. Before and after Columbus, many other brave seafarers were involved in this discovery of the Earth as a realistic, round ball rather than a flat disk. Most of them sailed west from Europe across the still unknown Atlantic. Or head south along the already known African coast. But it wasn't just the sailors. The Nuremberg craftsmen's guild and the Nuremberg navigator and merchant Martin Behaim (1459-1507) also played a major role at almost the same time. Behaim and Columbus lived almost parallel lives. They may not have known each other well, but theyhad similar goals in life during this period of great change from the late Middle Ages to the modern era. Behaim commissioned skilled and imaginative craftsmen from his Franconian hometown to design and construct the first real globe in the world. They were to glue, paint and inscribe it according to his specifications and wishes.

It is clear that by around 1492, when Columbus made his "discovery of America", Columbus was not alone in believing in a "round world". It is an established fact that seafarers were already aware that the Earth was a globe and not a soup plate, which tilted perilously downwards at the edge. As a cloth merchant in the service of the Portuguese king, Martin Behaim had also been on such voyages, often with a pounding heart to the edge of the horizon on the high seas. The main goal was clear: to reach India and the spice islands there.

However, his self-described "globe" shows nothing of "America", but is limited to the then known continents of Europe, Africa and Asia.The Greeks and Romans already knew about these in ancient times. Behaim's globe is therefore the first evidence of a new, scientific representation and measurement of the globe. He was not yet able to produce a correct cartography. The experience and carefully drawn maps of many courageous seafarers and captains of the coming centuries were still missing.

One half of the "Erdapfel" by Martin Behaim. Painted in Nuremberg in 1493/94; Germanisches Nationalmuseum Nuremberg

And again, it took decades of later voyages of discovery across the Atlantic Ocean to give the newly discovered "America" the name it has today and its existence as a continent in its own right. This was only achieved by another courageous captain, the Italian Amerigo Vespucci (1451-1512), who took a detour via South America and its northern coast.

It was a German cartographer, Martin Waldseemüller, of all people, who first used the name "America" for the new double continent on his then sensational and "true" world maps in 1507 (the year of Behaim's death). This general and sonorous name with four short syllables and the three vowels "a-e-i-a" then understandably prevailed over the following centuries It is clear that the new name for the New World had to be easily understood and quickly pronounced in dozens of European languages. However, the first explorer, Columbus, did not live to see this, as he would probably have been annoyed. He died a year earlier in 1506, incidentally in the firm, false belief that he had discovered the west coast of India. However, he would probably have been even more annoyed if he had had to admit at the end of his life that he had been thoroughly mistaken geographically.

So, it's fair to say that "America" was initially pretty stubborn about being seen as a "New World" by us Europeans. But was that because a lot of us, including a lot of Germans, thought we were already living in the "old first world"? So this was the first of the many times that "the Americans" had to put up with us conceited Europeans.

The English, Dutch, Spanish and French then took over North America and ruled it for about 300 years. During this time, Protestant ideas on religion, culture and society became more and more popular. These ideas were influenced by the Reformation of Martin Luther, Zwingli, Calvin and the English free churches.

More on this below. The Germans, especially the Catholics in the south up to the Alps, mostly stayed out of it. Or were they already asleep to developments in the world back then? Perhaps they were still so into their own culture, language and philosophy – in short, their soul and the Roman-Christian church – that they completely overlooked the first signs of absolutism in the 17th century and colonialism and imperialism in the 18th and 19th centuries?

The southern part of the "New World" on the western side of the Atlantic was reserved for the Portuguese and Spanish colonizers ("conquistadors", also Spanish-Catholic) to conquer. The sailor Columbus was still relatively peaceful, and probably didn't think so either. Furthermore, the indigenous populations of the north and south, erroneously designated as "Indigenous" and "Indios," respectively,were never asked about this. It is estimated that they were exterminated by the millions in the 16th and 17th centuries. This is believed to have occurred as a result of 'Christian' missionary wars and the introduction of diseases from other regions. From a global perspective, the discovery of America - as the process is still popularly called in Germany today - and the start of a planned, and at times criminal, colonization, which saw the destruction of the Aztec, Inca and Mayan empires and their ancient cultures in the 16th century, is what marks the start of the modern era.

This took place for centuries on the three biggest continents of America (with the indigenous peoples of the Indies, especially in the Spanish part), then in Africa (with the Dutch and English slave trade over to America in the 17th/18th century) and a bit later in Australia/New Zealand (with discrimination against the Maoris). Politically speaking, all this was triggered by a map that showed how the world was divided up between the two main maritime powers at the time of Columbus, Spain and Portugal. But this peace treaty had devastating consequences.

This all happened in the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, just two years after Columbus' first voyage of discovery. Spain and Portugal, the two maritime powers, shared their territories in the Atlantic from the North Pole to the South Pole along a longitude that put most of South America and part of Central America to the west under Spanish control, while Africa, India and Far Asia were to "belong" to Portuguese interests or their seafarers. This even happened with the blessing of the Roman Catholic world church and its pope at the time.

However, just two decades later, this encrusted, medieval church had to deal with the consequences of the Protestantism of a German, namely Martin Luther.This continued until the "Thirty Years' War" (1618-1648) in Germany and other countries.Perhaps the popes (until Pope Francis from Argentina in the 21st century) just didn't care as much about the terrible things the "Christian" conquistadors did in Mexico or Peru.

However, most of North America - the later USA and Canada - was not affected by the Treaty of Tordesillas. In the 15th and 16th centuries, these territories were still largely considered "terra incognita". At the time, no one could have predicted their global political significance.It was only with the "Glorious Revolution" in England and the victory of the English over the Spanish naval armada in 1588 that England started to rise as a world-dominating maritime power. This meant the start of a big colonial empire, which in the end (but only shortly before the final dissolution after the Second World War) extended from Canada and Australia to India as a "purified Commonwealth". This is why Queen Victoria even had herself crowned "Empress of India" in the 19th century - just before colonialism was coming to an end. So she was basically in charge of a huge empire, which was way bigger than any of the other 'empires' in history, like the ones of Alexander the Great, the Romans, the Spanish and Portuguese or even the Mongols, the Tsars or the Swedes and the French. Not to mention the imaginary, fascist "fake empires" of Mussolini and Hitler in the 20th century.

***

Even before the big voyages of discovery by European sailors around 1500, clever explorers, scholars, geographers, captains and nature observers knew that the earth was round, not flat like a disc. This bold statement was around long before Columbus' famous sea voyage. For a while, the Pope and the basic Catholic beliefs could defend themselves against this, even with cruel burnings of heretics, but then the scientific truth of the 'Copernican' revolution of the Catholic canon, astronomer and mathematician prevailed:

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543)was from Thorn in Warmia/Prussia. He published his most important work around 1543, called "De revolutionibus orbium coelestium", which translates as "the celestial revolution". In it, Copernicus came up with a new, scientific, astronomical and mathematical "true" heliocentric view of the world, with a fixed sun and its planets in their orbits. The great Italian scholar and mathematician Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) then proved Copernicus' theories right in 1611 in his work "Sidereus Nuncius". These theories were almost a hundred years old, but Galilei's astronomical observations (using new types of binoculars) and calculations were more precise. ***

And so the real "modern era" only really began around 1600 - and not with Columbus in 1492 or Luther in 1517, as is sometimes still told in German history lessons. This "Copernican" idea was rude, rude and shocking for almost everyone at the time, who looked up at the sun, moon and stars every day and night and had believed that everything they saw in nature was true. The so-called 'evangelicals' and those who uncritically support Trump are still doing the same thing in America today. Even Martin Luther, the most famous Protestant, demanded until the end of his life that the Pope and Emperor should burn all the Catholic writings from Thorn. So, the Protestant and Bible translator Luther was not at all a true "enlightener". Luther was probably only annoyed that the German Copernicus was Catholic and refused to join the Protestant church and Luther's criticism of the Roman papal church.

And yet, almost parallel to the life of Copernicus and his "Copernican Revolution", another huge revolution began at that time. This was also brought about by Martin Luther, a former German monk from Wittenberg in Saxony. Luther was joined by many other famous Protestants, including Melanchton, Zwingli, Calvin and Menno Simons. A major change in spiritual and religious life had long been in the air.

Today, all history books refer to this change as "Protestantism". It is not referred to as a "revolution" there, although it was one at the beginning of the modern era. One of these revolutions was not about science or maths, like the one that Copernicus caused. It was all about religion and spirituality, so it was still very medieval. But it also had big social and political consequences, more or at least faster than Copernicus, because of the weakening of the papacy, the rise of Anglicanism in England, Protestant movements in northern Germany and Scandinavia, the German "Luther Bible" and the creation of a standard High German language. This became more and more common, and was used more and more in Germany. But this "linguistic revolution" lasted for centuries in Germany and is still happening now.

Which of the two "revolutions" was more important and decisive for the modern era? It's not easy to decide: the term "Copernican Revolution" only slowly became established in the 17th century. For over 200 years, the Catholic Church was against a lot of new ideas. For example, it was against Galileo Galilei. It was also against the Protestant, German and Scandinavian national churches, as well as the Anglican Church in England.

The term "globe" was not yet common knowledge. The 'sphere model' by Apianus, from 1524, was still used officially in the Vatican and at most universities.

But why is this important? We'll look into this more in the next few chapters. These days, WASP has a new rival: WEIRD stands for Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic. It's not just about the USA anymore, but is aimed at the global, Western appeal of the New World. But it doesn't include today:

a) the problems and mutual disadvantages of migration from non-Western countries and continents to the old Western ones

b) the vague memory of former colonial dependencies and transgressions that were thought to be long gone.

c) the rise of the Asian and Pacific superpowers, China, India and Japan.

Perhaps the 16th and 17th centuries at the beginning of the modern era after the discovery of the two Americas should be described with two words:

The sudden realisation that the 'New World' was huge and truly spherical was soon followed by shock at the otherness and strangeness of the people there and their way of life. Then, a gold-hungry and bloody reaction set in from Europe, indeed like a shock. This occurred alongside two key insights held by many Europeans at the time: that the old medieval Christian world could no longer be considered the pinnacle of creation; and that significant power, gold and money could still be easily gained in the 'New World' — if one acted unscrupulously and selfishly!

2. The three deadly sins of the early modern period (16th/17th century)

The Catholic Church has known the "seven deadly sins" for almost two thousand years. Some of these ideas came from ancient philosophers and were subsequently elaborated in medieval Christianity.:

Superbia (arrogance, pride, arrogance)

Avariatia (avarice, greed)

Luxuria (lust, hedonism, unchastity)

Ira (anger, rage, a desire for revenge )

Gula (gluttony, excess, selfishness)

Invidia (envy, jealousy, selfish)

Acedia (laziness, ignorance, all forms of envy.)

The so-called "original sins", which have more of a theological and Old Testament background than a societal and social background, must be distinguished and distinguished from this.

For the early modern period, especially in the first two centuries, I would like to examine some of the deadly sins in the following global and historical events:

The voyages of discovery

The split

The heliocentric world view.

Re a) The voyages of discovery: The question must be posed: was there truly a necessity to abruptly seek a hasty "sea route to India" at the conclusion of the 15th century, driven by "envy" and "greed"? If the Vikings had produced a clever historian five hundred years earlier who could have written in Latin (but they didn't ...), then the later captains of the explorers' ships (from the Italian Columbus to the English Francis Drake) would probably have thought more carefully and possibly developed less "envy" and "greed". According to these (made-up) stories about old Viking captains, they would definitely have been more careful about the risks and uselessness of new continents (in those days without missionary and colonization mania). They wouldn't have taken such risky, expensive trips. That would have been two less deadly sins of modern times.

In Northern Europe, the Baltic Sea and the North Sea, there had already been an efficient, largely peaceful (apart from the danger of piracy with Störtebeker) Hanseatic economic alliance for 200 years, which was based on national, peaceful and economically liberal and equal (less warlike) relations. Couldn't/shouldn't this have been developed further instead of stealing pepper and myrtle from India and gold from the Mayas?

But no, the voyages of discovery to the west across the Atlantic were still motivated by Roman-Christian interests and not just economic and infrastructural ones. And the popes were still under the impression of the failed seven crusades in the High Middle Ages and they still wanted to convert the entire "flat" world to Christianity. And it was these other deadly sins of the popes and Christian kings and emperors ("pride" and "envy" of Islam) that then cost millions of people their lives and destroyed ancient cultures after 1492. In the early modern period, this happened through unrestrained colonization, greed for gold and absolutism in the subjugated colonies around America and Africa.

And of course, the voyages of discovery probably led to the development of modern technology. So, shipbuilding got better and new ways of moving stuff around were invented. But then they were also used in warfare and for armour, especially for black powder and cannons. This marked the end of the age of chivalry with its colourful and simple armour. Back in 1605, the Spanish national poet Cervantes kicked off the 17th century with his novel "Don Quixote de la Mancha", which was a massive hit. But getting rid of the heavy, fancy metal armour of knights and their horses wasn't just a sign of the medieval feudal knightly aristocracy falling apart. It also led to loads of soldiers and men dying in cruel, mechanized and later even industrial ways in all wars. Was it not always only in the post-war period that "progress" could really develop and take hold in the subsequent peacetime? One of the deadly sins from the time of the voyages of discovery is the connection between racism and slavery (also based on "envy", "greed" and "gluttony"). Unfortunately, there have always been arrogance and a sense of superiority among some people over others. But at the beginning of Homo sapiens, these were more regional clan struggles or later class struggles in antiquity and the Middle Ages, as Karl Marx - sometimes quite aptly - described them. For example, the so-called "modern and clever" human being (after the apes) probably wiped out the rather peaceful but "technically" and technically unskilled Neanderthals in Central Europe around twenty to thirty thousand years ago after the last great ice age.

As the Swedish Nobel Prize winner Svante Pääbo recently found out when he compared the genes of modern humans with those of the Neanderthals from the famous valley near Düsseldorf, we humans still have remnants of Neanderthal genes in our bones and skulls today. You can prove this today with both archaeology and medicine. So, 30,000 years ago, there must've been "Romeos and Juliets" from the two hostile La groups, like the old (still stupid) and the new (already clever) humans. Fun fact: the latter even came to Europe from Africa via the Mediterranean and the Near East! But the fact that in modern times the mixing of people in all five parts of the world ultimately led to a massive deportation and enslavement of people, mostly from Africa and mostly over to North America, is unfortunately a monstrous disgrace and another mortal sin of the so-called "white race".This white "race", which has mostly migrated to America from Europe, has pretty much decided that it's the superior, even the "chosen race" of God ("Superbia", "Gula"). It's been ruthless in how it's taken advantage of its power and tricked itself into thinking that's what it's supposed to do, ignoring all the basic rights that people should have.

In the 19th century, at the beginning of colonialism, Europe also played an inglorious role in its neighboring part of the world, Africa. Some "researchers and scholars" with rather questionable foundations and ideas tried early on to justify their feelings of white superiority "scientifically" and in terms of evolutionary history. Carl Gustav Carus' (1789-1869) 1849 paper with the arrogant title "The unequal capacity of the various human tribes for higher mental development" played a disastrous role in this. Such a thesis could not be proven either medically or historically. Carus himself was a doctor, gynecologist, anatomist and pathologist, as well as a romantic painter and psychologist in Saxony. He even published his work on the 100th birthday of the Weimar classicist Goethe, who was unfortunately already dead, in order to respond appropriately by emphasizing the Enlightenment and human rights (see: Chapter 4: "The Dawn").

Carus obviously also misunderstood Charles Darwin's new theory of evolution and thus promoted colonialism and imperialism (see chapter 10). But basically, even in the 19th century, the German pseudo-scientist Carus can still be assigned to the deadly sins of whites since the Middle Ages and early modern times: above all pride and greed.

Carus speaks of "day and night peoples": in his opinion, the white Europeans belong to the former, the dark-skinned people from Africa to the latter: "As for the African Negroes (...) they have never at any time been able to create a higher state constitution among themselves, they have never received a literature or a concept of higher artistic views and artistic achievements (...)" (see: Bibliography, op. cit. Richard Nate, "Strange Visions of Outlandish Things", pp. 143-47)

Carus draws an analogy between skin color and the time of day. I was wondering if he might've picked this up from the German words "Abendland" and "Morgenland", but not in a scientific way. The Romans originally used "occident" to refer to the western part of Europe, i.e. the Latin-speaking Roman provinces. The word "Occident" did not appear in Germany until 1529. The Christian Romantic poet Novalis (1772-1801) used it programmatically in his work "Christendom or Europe". The two brothers and German Romantics August Wilhelm and Friedrich Schlegel did the same. They, too, used it to delimit and enhance the light-filled, "old" continent of Europe.

Africa, the 'black' continent, has been marginalized here, but it was only 'really' 'discovered' in the 19th century by European imperialists and colonialists. But the Americans, especially the plantation owners in the southern states, were also happy to use Africa as a kind of free recruitment reservoir for their slaves during this period. At least until the end of the War of Secession.In his new book (see above), Richard Nate speaks of an interesting correspondence between "early modern cosmology and a Judeo-Christian-inspired metaphor of light" (Nate, op. cit., p. 147). According to this, the "day peoples" would be found far to the east in India, China and Japan, more precisely: as "twilight peoples" who were the first to enjoy the sunset for the day. This was followed by the Orient and the Middle East as the "Morning Land" and finally Europe with the Mediterranean as the "Occident or Occident", as in medieval writings. For Africa - not quite geographically correct - only the black "night peoples" remain. There is no place at all for America in this classification, as it still corresponds to the flat, disc-like and childlike world view of Europeans up to 1492, when the sun was supposed to move and had to rise in the east and set in the west. Whether it wanted to or not. But humans (homo "sapiens") wanted it that way with their earthly, Stone Age brains. The Western Europeans, enlightened and shocked by Copernicus (heliocentric world view, see chapter 1), should have known much better. But they didn't want to believe it, not even our "reformer" Luther.

And indeed, after Columbus and Copernicus, people could have introduced an "eighth" deadly sin - namely the deadly sin of error. Of course, this would only have applied to Columbus and his discoverer imitators, not to the strict astronomer Copernicus himself and his scientific students.

Clearly, in the 19th century, well after the "dawn of the European Enlightenment", Carus proclaims a European claim to power over all other peoples of the world. However, he deliberately overlooks the long-discovered regions of North and South America or does not consider them comparable to the Europeans and Germans in the real, old "Occident" (deadly sins: "pride, envy, sluggishness of spirit, error").

Remarkably, large and non-Christian countries in Asia - India, China and Japan - initially resisted such colonialist temptations in the 19th century. But then, only in the infamous 20th century, they too committed imperialist, nationalist and racist crimes such as those prepared here by Carus - perhaps not explicitly, but indirectly. Nate even says that this work by Carus was a standard model in the 19th century, and not only in Germany. He refers to the book by the Englishman Edward Burnett Taylor: "Primitive Culture" from 1871, in which humanity is divided into "civilized" and "barbarians" or even "savages" (see Nate, op. cit., p. 146).

Regarding b) The schism: In 1517, Luther's posting of his theses at the castle church in Wittenberg marked the beginning of the schism in the world church of Christianity, which was now more than a thousand years old. The latter had risen very powerfully and quite unexpectedly and impressively from the Roman Empire (republic plus empire) and worked its way up to the medieval papacy. The popes have also always had strong, more secular-minded opponents, who formed oppositions from the common people as German emperors, electors, landed gentry or even in isolated peasant revolutions (Stedingen Uprising 1234, Peasants' Wars 1524/25). Over the course of centuries, this gave rise to a kind of original form of the separation of powers, which still forms the principle of the secular state and people against the ecclesiastical church and papacy in Western democracies todayWell, up until the schism at the start of the modern era, the Roman Church had pretty much the whole of Europe under its control. So, along with Judaism and Islam in the Middle East and as far as India and China, it was the world's third global mono-theology, with the belief in just one God. Well, there's Yahweh, Jesus/God and Allah.

In 1618, almost exactly one hundred years after Luther's first protest action - with which he originally only wanted to purify or "reform" the papal church - the Thirty Years' War (1618-48) began in the center of Europe. With "pride", "greed" and "envy" on all sides. A great religious war developed between the Protestant modern and the old Catholic, still medieval powers in Europe. This happened after a busy, difficult and chaotic 16th century, when most people still thought of the Middle Ages as the present, and the modern age was still in the process of being born. The consequences were: Reformation and Counter-Reformation, disunity among Protestants: Lutherans against Anabaptists, Mennonites, Calvinists, Zwinglians and other "free churches", the founding of the militant Jesuits by Ignatius of Loyola (as a Catholic counter-proposal to Luther), Lutheranism and the "Counter-Reformation". Lutheran regional churches were pretty united, with princes and Protestant preachers working together ("Cuius regio, eius religio"). Then there were the Schmalkaldic wars against Catholic countries, the Huguenot wars in France, the Spanish-Dutch war, the Catholic monarchies getting stronger under Emperor Charles V and Philip II in Spain. Also, an English Anglican church was founded under the protection of a growing English kingdom that was, in principle, Protestant. And let's not forget the gold rush and the greed for power of the Spanish and Portuguese in their first colonies in Central and South America.

Around the turn of the century in 1599/1600, these civil wars in the fierce struggle for Christian sovereignty gradually and logically turned into a massive European war, namely the Thirty Years' War, which was triggered in 1618 by an almost ridiculous event, the Defenestration of Prague Castle, and was then largely fought on German territory - with the participation of all the major European powers with varying degrees of intensity.

Martin Luther had absolutely no idea of this. Nor did he ever want it that way. His political and historical understanding did not actually extend beyond his favorite topics, namely the High German translation of the Bible, the theological exploration of his own "conscience" and, at most, the creation of a magnificent, German standard and unified language. In doing so, he more or less unwillingly triggered an enormous popular uprising and mass education through the new printing press (Johannes Gutenberg).

But at first, the great and not at all Christian war fury still prevailed in Europe ("Superbia" and "Avariatia"). It was led by the then Swedish superpower under its king Gustav Adolf with the support of several northern German Protestant principalities and the mercenary leader Albrecht Wallenstein, who had been recruited and paid by the Catholic German Emperor Ferdinand. The early death of the Protestant Gustav Adolf at the Battle of Lützen in 1632 and then the subsequent rampant greed for power and money (deadly sins) of commander Wallenstein and the weakness of the Catholic emperor led to the atrocities and devastation in Germany that have become proverbial. With the "Peace of Westphalia" in Osnabrück and Münster, the great war finally ended more or less undecided. Overall, the German regional principalities had suffered the worst damage. France was able to continue and expand its rise under King Louis XIV, the "Sun King". From then on, Sweden had to struggle hard to maintain its claim to remain a major European power - also in rivalry with Russia and the new Tsar Peter the Great. The northern European centers of gravity, the Netherlands and England, both maritime powers, increasingly shifted their interest from Europe to the acquisition of colonial territories in the newly discovered world, i.e. "overseas".

So after around 250 years between 1500 and 1750, the religious schism in the modern era had no clear winner. Rather, after a long struggle, the European states had lost ground everywhere. All of the aforementioned "deadly sins" - carried over from the High Middle Ages - had caused negative effects. The countries of discovery since 1492, namely Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, England and France, also had to slow down their claims and hopes for the expansion of in the new continents, but were soon able to resume them. Here too, however, there were important decisions: France largely withdrew from North America at the end of the 18th century following the French Revolution. Spain and Portugal were pushed into Central and South America - also by the young and strengthened USA - or even into distant Asia (Goa). The Netherlands also eventually relinquished its claims more or less without a fight. When their foundation "New Amsterdam" on the east coast of North America was renamed "New York" by the English in 1664, it was clear that at the end of the 17th century only England was left as the shining victor of the old explorer countries, having already pushed Spain aside.

However, this victory was soon put into perspective by the flight of the English colonialists in North America and their quest for independence from the British crown and their home state. See below (see chapter 5).

c) The heliocentric world view: The realization that our earth is a spherical planet around the fixed sun did not excite many people at the time, but initially disturbed and outraged them. This is why the Catholic Church was able to hold on to the "flat disk" postulate for over a century (until Galileo and Kepler) in the 17th century. And there are some "lateral thinkers" who still believe this today in the 21st century (deadly sins of "anger and pride" and, of course, "error", which are even widespread among all climate deniers today, including Trump and his blinded followers). And just as Columbus had to defend himself throughout his life against stubborn popes (the deadly sin of "indolence"), circumnavigator Boris Herrmann from Oldenburg still sees the world-saving necessity of writing "Unite behind the Sciences" on the huge mainsail of his racing yacht. In other words: "Unite behind the truths of the natural sciences!" Scientific studies, geography, medicine, technology and sea navigation by satellite should never be silenced by politicians like Trump or Bolsonaro today. These politicians are still spreading their lies and denying the facts about climate change and the destruction of nature via social media and other formats " (and by no means "facts").

Fortunately, the heliocentric view of the world prevailed after about 200-300 years. But the fact that it took so long (mortal sin: "inertia") was not only due to the resistance of the church and the powerful, but also to the slowness and sluggishness of ordinary people (modern mortal sin to this day: "error"!). Some people simply did not and do not want to believe in the scientific evidence or do not understand it at all. Back around 1500, it was also pretty hard to change how people thought about the world and what it meant to be human. It was a real struggle to move away from seeing humans as a special creation of a god (like "subduing the earth") and more in tune with the fact that we're just a small part of this big nature world. Christianity, especially in the New Testament, talks about this a lot (like the idea that everyone is equal, being humble towards all living beings, and the commandment of peace in Jesus' Sermon on the Mount).

Every human being - and not just popes and kings - first had to realize that he/she was not the crowning glory of creation, but just a small part of the grand tapestry of life (Charles Darwin/Alexander von Humboldt: see chapter 9).

This was a pretty shocking and eye-opening realisation for people in the 16th century. I was just wondering if this could also be a psychological reason for the chaos of the time? How were people supposed to cope with that so quickly back then? We've had five hundred years to get used to it. And some still haven't managed to do so. And don't you think we're facing a similar situation with space exploration right now? I'm talking about going to the rocky Moon (which takes two weeks) or to dusty and icy Mars (which takes two years) or even outside of “our” Milky Way (which is only possible in millions of light years!).The captains of the explorer ships and their crews, as well as the Protestants around Luther and his followers, who were infatuated with their own spiritual certainty and "conscience", could at least dream of a great future. Only those who did not want to do so had to struggle to avoid devaluing their own human existence. Just as a large part of the new Jesuit order did during the Counter-Reformation, especially in Spanish and Portuguese South America.

The refusal to accept the heliocentric view of the world can therefore be described as the most understandable, indeed the most human, of all the deadly sins of the Middle Ages. However, one cannot derive a "human right to scientific error" from this, as seems to be the case today with some lateral thinkers against compulsory vaccination or with the denial of climate tipping points.

***

3. Fleeing to the colonies from war and absolutism in Europe

Since we want to concentrate here on the German view and perspective on North America and Canada, we have to neglect Central and South American colonial history with Spain and Portugal for the time being. Even at the beginning of the Thirty Years' War (see above) in the 17th century, England took a small but historically huge step forward in the conquest of its North American colonies on the coast north of today's Boston and Massachusetts. And unlike the Vikings (see above), they remained there for the next 250 years and gradually expanded their colonial acquisitions and conquests - albeit at the expense of the "Indian" (today: "indigenous") natives.

The two-master "Mayflower" set off from Plymouth on 6 September 1620, just like Sir Francis Drake had done 40 years earlier on his first complete circumnavigation of the globe. They landed after ten hard weeks of sailing on 21 November, just before winter, near the present-day village of Provincetown on Cape Cod, north of Boston. . On board were 102 passengers: men, women and children from a Protestant sect of "Pilgrims" who were persecuted in England and were seeking their freedom of faith and person in America. These English Protestant refugees - or more precisely: those expelled by the Anglican state church - went down in American founding history as the "Pilgrim Fathers". They came from central England and their descendants in the USA still enjoy the status of colonial aristocracy today. However, in the fall and winter of 1620 - the war fury was already raging in Germany and Europe - the Pilgrim Fathers and their families were also in a miserable state. Only with great effort and with the initial help of "indigenous people" were they able to build grass sod winter houses, which have been rebuilt there today for tourists. This was the only way the English refugees were able to survive the cold storms, ice and snow of the first winter. Nevertheless, many died of pneumonia or tuberculosis.

The "Pilgrim Fathers" were Calvinists or radical Puritans who had left their homeland in opposition to the "Church of England" (also a product of the "religious battles" in the 16th century, see above). They strove for absolute, equal congregational autonomy and believed that they were only directly subordinate to God and Jesus Christ. They even rejected the Christian sign of the cross and Christmas as an ancient pagan custom because they found no evidence of it in the Bible, despite intensive searching and no longer in Latin, but in their native English language.

They signed the Mayflower Treaty, in which they committed themselves to democratic principles in the sense of a self-governing, free community ("self-rule, self-government"). In a way, this was the "Rütli Oath" of the first European immigrants in North America and the later USA. The Pilgrim Fathers made a sacred promise to themselves that they would create "just and equal laws" for all people and live by them. This form of government would correspond solely to God's will for all people in equality and freedom.

These ideas, simple in principle, arose among the almost one hundred people fleeing oppression and feudal bondage in Europe. In 1621, they signed a peace treaty with the chief of the Wampanoag natives. For several decades, relatively harmonious relations with the natives developed with the arrival of other settlers from England. However, from 1637 onwards (Pequot War), tensions increased. The "King Philip's War" of 1675-76 is a name that's really got a lot of history behind it. It's a name that brings to mind a time when the indigenous people of the area we now know as Massachusetts were so weakened by the influx of immigrants that they never really recovered, with an estimated 3,000 of them losing their lives. The white settlers from England had triumphed in America with white "pride" or with merciless "anger"? Or even with a "greed", despite their naive, original Christian ideology from the old days of persecution of Christians in the Roman catacombs?

***

The same kind of thing happened in the areas of the English colonies around Virginia and Philadelphia further south. Some of these were even set up before the Mayflower even landed at Cape Cod. The Pilgrim Fathers' goal in 1620 had been the small English settlements further south, which were already there. However, they were unable to reach them due to adverse weather conditions.

Even further back in time, Sir Walter Raleigh made an expedition to the west coast on behalf of Queen Elizabeth I in 1584 and named his occupied territory "Virginia" ("Virgin Queen") in honor of the unmarried Elizabeth. Unlike his rival Francis Drake, Walter Raleigh was even more successful in winning the Queen's favor in the long term than the privateer captain and buccaneer Drake. However, you have to think far ahead, namely to the founding of the USA at the end of the 18th century. None of them could have foreseen this, neither Raleigh, Drake nor their Queen Elizabeth the First.

As early as 1607, a more or less private "Virginia Company" was formed, which built the small settlement of "Jamestown". As early as December 1606, it attracted a group of Protestant religious refugees from England with 144 men. However, only 38 of these were still alive in 1607, all the others having died of hunger and disease. Nevertheless, more refugees flocked to the New World. And when a certain John Rolfe discovered the tobacco plant as a favorable economic asset in North America in 1612 and harvested it for the first time, an economic upswing began. Tobacco grew well in Virginia's humid climate. Before that, though, "the whites" from England were still at war with the indigenous people. These were various tribes: the Powhatan, Iroquois, Nottaway, Meherrin, Sioux, Monacan and Cherokee.

More and more immigrants also came from Germany, most of them as Protestant religious refugees. People from the Siegerland region were the first to establish the "Colony Germana" (not Germania) in 1714. In regional history they became known as the 'good old Germans'.