Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pocket Essentials

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

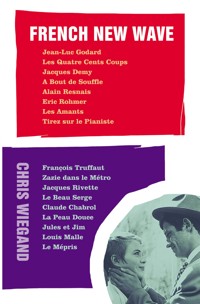

The directors of the French New Wave were the original film geeks - a collection of celluloid-crazed cinéphiles with a background in film criticism and a love for American auteurs. Having spent countless hours slumped in Parisian cinémathèques, they armed themselves with handheld cameras, rejected conventions, and successfully moved movies out of the studios and on to the streets at the end of the 1950s. By the mid-1960s, the likes of Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and Claude Chabrol had changed the rules of film-making forever, but the movement as such was over. During these key years, the New Wave directors employed experimental techniques to achieve a fresh and invigorating new style of cinema. Borrowing liberally from the varied traditions of film noir, musicals and science fiction, they released a string of innovative and influential pictures, including the classics Le Beau Serge, Jules et Jim and A Bout de Souffle. This Guide reviews and analyses all of the major films in the movement and offers profiles of its principal stars, such as Jean-Paul Belmondo, Anna Karina and Brigitte Bardot. An introductory essay, Making Waves, examines the social context of the movement in France as well as the directors' considerable influence on later generations of filmmakers across the globe. A handy multi-media reference guide at the end of the book points the way towards further NewWave resources.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 167

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The directors of the French New Wave were the original film geeks - a collection of celluloid-crazed cinéphiles with a background in film criticism and a love for American auteurs. Having spent countless hours slumped in Parisian cinémathèques, they armed themselves with handheld cameras, rejected conventions, and successfully moved movies out of the studios and on to the streets at the end of the 1950s. By the mid-1960s, the likes of Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and Claude Chabrol had changed the rules of film-making forever, but the movement as such was over.

During these key years, the New Wave directors employed experimental techniques to achieve a fresh and invigorating new style of cinema. Borrowing liberally from the varied traditions of film noir, musicals and science fiction, they released a string of innovative and influential pictures, including the classics Le Beau Serge, Jules et Jim and A Bout de Souffle.

This Guide reviews and analyses all of the major films in the movement and offers profiles of its principal stars, such as Jean-Paul Belmondo, Anna Karina and Brigitte Bardot. An introductory essay, Making Waves, examines the social context of the movement in France as well as the directors’ considerable influence on later generations of filmmakers across the globe. A handy multi-media reference guide at the end of the book points the way towards further New Wave resources.

Chris Wiegand writes for Boxoffice Magazine, Film Threat, Crime Time and bbc.co.uk.

He is also the author of Federico Fellini: The Complete Films (Taschen).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Paul Duncan for providing unlimited editorial guidance and enthusiasm. Further assistance came from Shannon Attaway, Mylene Bradfield, Louise Cooper, Julia Dance, Lisa DeBell, Alexis Durrant, Lizzie Frith, Maria Kilcoyne, Steve Lewis, Wade Major, Ion Mills, Luke Morris, Gary Naseby, Matt Price, Jill Reading, Jessica Simon, James Spackman and Claire Watts. Merci à tous!

1. Making Waves: An Introduction

Beautiful women. Suave leading men. Existential angst. Black and white figures in Parisian cafés. Cigarette smoke. Lots of it.

The world of French cinema conjures up a hundred often-parodied clichés for today’s viewer and the films of the New Wave era supply their own set of distinctive images. Jean Seberg walking down the Champs Elysées selling the New York Herald Tribune. The young Jean-Pierre Léaud running through the streets of Paris with a stolen typewriter. Charles Aznavour playing honky-tonk piano in a run-down café. Anna Karina and Jean-Claude Brialy brushing off their feet before going to sleep. Eddie Constantine, decked out in gumshoe hat and mac, arriving at the sinister town of Alphaville. Jean-Paul Belmondo wrapping dynamite around his painted face. Brigitte Bardot lying naked in a bedroom asking Michel Piccoli what he thinks of her rear. Jeanne Moreau, Oskar Werner and Henri Serre cycling through the countryside. The list is endless.

These images are some of the things that the New Wave means to me, yet decades after the term ‘Nouvelle Vague’ was coined in L’Express magazine, critics continue to argue over its precise meaning. Some confine the New Wave to a certain period of time, others to particular directors. Many believe that the filmmakers who wrote for the influential journal Cahiers du Cinéma are the only ones we can truly describe as belonging to the New Wave. Among the directors believed at one time or another to be related to the movement are: Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, Alain Resnais, Louis Malle, Roger Vadim, Jacques Demy, Agnès Varda, Chris Marker, Jean Rouch, Jacques Rozier, Jean Douchet, Alexandre Astruc, Pierre Kast, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Jean Eustache.

This book doesn’t set out to cover every film made by every filmmaker connected with the movement. Instead, it looks at the early years of the movement and follows roughly a decade of filmmaking, from the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s. This was a time when the New Wave had a certain sense of cohesion, if not in real life then often thematically and stylistically on the screen.

In choosing the films to be covered, I have primarily given space to those works that made their directors’ reputations during these years. As the temporal bias would have led to the exclusion of key critical and commercial successes, such as Truffaut’s Le Dernier Métro, Chabrol’s Le Boucher and Rivette’s La Belle Noiseuse, I have included a checklist of other New Wave-related films at the end of the book.

Everyone’s a Critic

Before examining their films, it is worth remembering that the principal New Wave directors started their careers as critics. Many continued to write criticism while filming their own works, seeing themselves as both critics and filmmakers. This is not to say they were mere movie reviewers. They essentially redesigned the role of the film critic, recognising the medium as on a par with the other arts and giving detailed analysis to directors who had never before been treated with much respect. The birth of this new form of criticism – and of the New Wave itself – owes much to two men: Henri Langlois and André Bazin.

Across Paris at the end of the 1940s there was a large number of cinema clubs, where audiences could view home-grown and foreign films, then discuss them to their heart’s content. One of the best was Henri Langlois’ Cinémathèque Française, which was co-founded with Georges Franju (who went on to direct Les Yeux Sans Visage) and opened its doors to cinéphiles in 1948. The Cinémathèque was a place for learning, not just watching. The cinema was small but Langlois had archived a wide range of films from around the world to screen to his eager audiences.

Many of the films shown in the cinema clubs at this time were American. During the Occupation, the import of Hollywood films to Europe had been banned by the Nazis so the French public had missed out on a period of particular fertility in US cinema. After the war, these missing films filtered through to France in rapid succession. This meant that between 1946 and 1947 the young French critics were given a crash course in roughly ten years of American cinema, including masterpieces by the likes of John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock.

It was at the Cinémathèque Française that the principal movers in the New Wave originally met. One of the key figures, François Truffaut, already had an especially intense and involved relationship with the cinema. He had turned to films at an early age, finding them a kind of refuge from his unhappy home life with his mother and stepfather. Truffaut’s teenage years were dogged by petty crime and a spell in a young offenders’ institute. The cinema managed to give his life some sort of focus.

Jean-Luc Godard had a similarly passionate relationship with the movies. Godard was born in Paris but spent his childhood in Switzerland. Returning to his native France, he studied ethnology at the Sorbonne but before long found himself studying cinema in a far more intensive fashion at the Cinémathèque. His passion was also linked to a form of escapism. In his introduction to a volume of François Truffaut’s letters, Godard described the cinema screen as ‘the wall we had to scale in order to escape from our lives.’ Rumours of the pair’s early viewing sessions have reached mythic status. At one point, Godard alone was said to be watching around 1,000 films a year. But the life of the average cinéphile involved more than just viewing films. Stills and posters were collected, credits were studied for familiar names, and lists were compiled of favourites from different countries. Everything was done to put the work on screen into some kind of perspective.

Godard was intent on setting up a film journal that he could write for. He did so with Jacques Rivette, a young man from Rouen, and Eric Rohmer, a former literature teacher from Nancy. Entitled La Gazette du Cinéma, this publication was to appear irregularly but, nevertheless, provided the critics with a suitable stamping ground to discuss the many films they were watching. Truffaut, Godard, Rohmer and Rivette, along with a young intellectual named Alain Resnais, were soon writing for a variety of magazines, including Arts and Les Amis du Cinéma.

The most important journal was Cahiers du Cinéma (formerly La Revue du Cinéma), which featured reviews and general discussions on cinema theory. The journal was founded in 1950 by André Bazin, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Lo Duca. The first issue hit the streets in April 1951. Rohmer, Godard and Rivette joined the journal in 1952. Rohmer went on to edit it from 1956 to 1963. At the time he joined, Cahiers was edited by Bazin, who had also run his own cinema club during the Occupation. At Cahiers, Bazin became something of a surrogate father to the young men and helped educate them in a manner similar to Langlois. He was to share a particularly close relationship with Truffaut who, after a brief meeting with the older man, had written to him from the young offenders’ institute begging for help.

Favourite Filmmakers

The caustic Cahiers critics styled themselves as a ‘band of outsiders’, to quote the title of one of Godard’s films. They were united by their disdain for the mainstream ‘tradition de qualité,’ which dominated the French film industry at the time. In a famous essay for Cahiers entitled Une Certaine Tendance du Cinéma Français, published on New Year’s Day in 1954, a 22-year-old Truffaut set out the New Wave’s argument against the restrictive uniformity of the ‘tradition de qualité’. Such filmmaking was confined to the studios and presented run-of-the-mill stories in an old-fashioned and unimaginative glossy style. These pictures were made with one eye firmly on the box office and they rarely challenged viewers. Singled out for criticism in Truffaut’s article was the dominating role played by the scriptwriter. This outdated brand of cinema simply wasn’t visual enough for the young critics, who quickly renamed it ‘cinéma de papa’ and took their inspiration from elsewhere.

They praised the French directors of an earlier era, such as the great social commentator Jean Renoir (La Grande Illusion) and the Poetic Realist Jean Vigo (L’Atalante), alongside contemporaries who had successfully made films outside the studio system, such as Jean-Pierre Melville (Le Silence de la Mer), who would become recognised as the godfather of the New Wave. The fact that Renoir and Melville not only directed, but also either wrote, produced or starred in many of their features particularly inspired the Cahiers crowd. Other French filmmakers admired by the critics included Henri-Georges Clouzot (Le Corbeau), Robert Bresson (Mouchette), René Clément (Jeux Interdits) and the collaborative works of Marcel Carné and Jacques Prévert (Les Visiteurs du Soir).

The critics looked outside France to find other directors who either refused to play the studio game or attempted to subvert it from within. Fritz Lang influenced them all. Godard would later cast Lang in his 1963 picture Le Mépris. Both Lang’s early German work and his American movies inspired the New Wave critics. A number of distinctive American directors were extremely influential. The critics were never hierarchical when it came to praising filmmakers and gave American B-movie directors such as Sam Fuller (Shock Corridor) and Jacques Tourneur (Cat People) a level of respect many found hard to understand at the time. These days, critical studies of Hitchcock dominate the film section of any bookshop, but Chabrol and Rohmer’s decision to write a book on Hitch was considered extraordinary in the 1950s.

Another European influence on the New Wave was Italy’s neorealism movement. Directors such as Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio de Sica showed that it was possible to make dramatic and incredibly moving films outside the studio, working on location and using non-professionals who often improvised their lines. Neorealist directors removed the heavy noise insulation from cameras, using them in a hand-held fashion and shooting without sound, which they post-synchronised later. The neorealists showed the financial advantages of such a style of filmmaking, as well as the liberating creative advantages.

La Politique des Auteurs

This personal approach to filmmaking appealed to the New Wave critics, who were by now recognising the importance of the director as an auteur. That is to say, they believed that of all the people involved in the making of a film, the director is the only real author of the end product. This is a theory that is pretty much taken for granted these days, as people will speak of going to see ‘the new Woody Allen film’ or ‘Spike Lee’s latest,’ but in the 1950s it was considered a radical new approach. Previously, films had been viewed as the product of a particular studio or producer and less respect had been given to the director.

Of course, this theory was not true for every film produced. As exponents of the auteur theory, the New Wave critics singled out Americans such as Nicholas Ray, Orson Welles, Howard Hawks and John Ford, whose works they had enjoyed at the Cinémathèque. They demonstrated convincingly, in essays for Cahiers, that the films of such directors consistently bore the unique mark of an individual, just as the collected novels of a certain author were commonly accepted as bearing similarities in terms of style, theme and subject matter. In the auteur fashion, films were equated with other works of art and were not considered – as had been commonly accepted – the product of a mass commercial operation. To look at films as the product of a sole imagination and not a faceless studio beast required that the cinema be viewed as more personal and intimate than ever before.

The critic Alexandre Astruc had put forward the notion of the ‘caméra-stylo’ or ‘camera-pen’ in an article in L’Ecran Français, in March 1948, and his manifesto had been quickly accepted by the Cahiers critics. In the essay, Astruc argued that the cinema could have its own ‘language’ just like the other arts. The Cahiers critics’ writings meant that cinema’s low-brow reputation and short history were reassessed. Suddenly, certain westerns and gangster movies were equated in terms of artistic merit to impressionist paintings and classic novels.

First Filmmaking Experiences

Not content with watching and writing about films, the Cahiers critics wanted to get to grips with the film industry from a variety of angles. Chabrol worked for a period as a publicist at 20th Century-Fox, where he was also able to secure a job for Godard as a press agent. Godard also worked for the Swiss national TV network, while Truffaut gained some experience in the film unit of the Ministry of Agriculture. Some were lucky enough to learn their craft alongside their cinematic idols. Truffaut cut his teeth with Max Ophüls and Roberto Rossellini. Jacques Rivette worked with Jean Renoir and his disciple Jacques Becker (Touchez Pas au Grisbi). Louis Malle collaborated with the explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau and with Jacques Tati and Robert Bresson.

By the early 1950s the Cahiers critics had started to make their first short films. Rohmer directed Journal d’un Scélérat and Charlotte et Son Steak while Chabrol wrote the screenplay for Rivette’s first short, LeCoup du Berger. Financial backing was sometimes hard to find for these first cinematic ventures and each of the young directors had to devise new ways to gain funding. Godard was perhaps the most successful among them. In 1952 he wrote, produced, directed and edited the 20-minute documentary Opération Béton, which concerned the building of the Grande Dixence dam in Switzerland. He made the film with the wages he had earned working as a labourer on the dam and, once it was completed, he sold the documentary to the company which had undertaken the work on the dam, thus providing the funds for his own first dramatic shorts.

A New Formula

When the Cahiers critics came to make feature films themselves, they knew that they would be made firmly in the auteur’s mould. But how would the opportunity come about? Filmmaking had always been an expensive business. It was extremely hard to make a film without the financial backing of a major studio. The equipment involved was costly and hard to come by. The explosion of the New Wave onto cinema screens across France and around the world came down partly to coincidence. As it happens, the critics were forming such notions of independent filmmaking at a time of great technological and social change, that would help them put their notions into practice. As the money-grabbing movie producer Battista comments, in Alberto Moravia’s novel Il Disprezzo (filmed by Godard as Le Mépris), ‘The after-the-war period is now over, and people are feeling the need of a new formula.’

After the war, the Gaullist government brought in film subsidies for new productions and filmmaking equipment itself also became cheaper, due partly to the rise of television. Developments in documentary filmmaking meant that lighter and cheaper hand-held cameras had become more widely available and affordable to young directors. Faster film stock that could be used in darker conditions (thus outside the studio) had also been successfully developed. Synchronous sound recorders and lighting equipment became equally affordable and portable. These breakthroughs meant directors no longer needed a studio to make a film, as real locations provided free, authentic backdrops. Crews became smaller and in general the critics were able to make their first films very cheaply. Suddenly, filmmakers had more choice over the kind of film that they wanted to make and who would appear in it.

The odds for the finished product were also changing. Before this time, anyone venturing to make their own film outside of help from the studios would see that film given an extremely limited release, mainly in the obscure arthouse cinemas. Because of the US government’s anti-trust legislation, which effectively ended the studios’ domination, smaller films successfully received more widespread distribution. For the first time they were screened at mainstream cinemas as well as arthouse venues. The New Wave reached the cinemas and audiences were unable to ignore it.

A Portrait of Today’s Youth

This collection of circumstances signalled record numbers of first-time filmmakers in France. Over 20 directors released their first films in 1959 and this number doubled in the following year. These figures were extraordinary for the time. In the 1950s most directors made their debut at around the age of 40, after serving a lengthy apprenticeship. Remarkably, not only were these youngsters making their own films, many were doing extremely well at the box office.

Filmmaking was suddenly a fresh and vibrant force, as new pictures were made by, for and starring young people. In the 1950s, this coincided with the American youth culture explosion created by rock and roll. When Roger Vadim’s Et Dieu…Créa la Femme was released in America in 1957 it was heralded as a female, French counterpart to the quintessential American youth movie Rebel Without a Cause. Many New Wave films spoke to young audiences about their lives. They were shot in the present day and applicable to modern issues, unlike the outdated costume dramas churned out by the ‘cinéma de papa’.

The playfulness, rebelliousness and inventiveness of the first New Wave films reveal the tender age of their directors. It is telling that the term ‘Nouvelle Vague’ was coined in a 1957 article in L’Express that was entitled ‘Report On Today’s Youth.’ The article, written by the journalist Françoise Giroud, dealt primarily with society, as did the book she published the following year, The New Wave: Portrait of Today’s Youth. The phrase ‘new wave’ was bandied about to represent a whole generation as well as a filmmaking movement. However, the term stuck to the cinematic works that kicked up a storm two years later at the Cannes Film Festival.

New Wave Style

So how can we define a New Wave film? A clue is offered by a character in Godard’s 1962 picture Vivre sa Vie