26,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

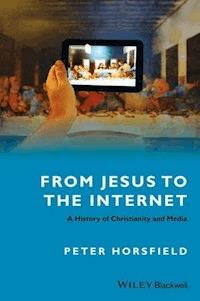

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

From Jesus to the Internet examines Christianity as a mediated phenomenon, paying particular attention to how various forms of media have influenced and developed the Christian tradition over the centuries. It is the first systematic survey of this topic and the author provides those studying or interested in the intersection of religion and media with a lively and engaging chronological narrative. With insights into some of Christianity's most hotly debated contemporary issues, this book provides a much-needed historical basis for this interdisciplinary field.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 683

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

From Jesus to the Internet

A History of Christianity and Media

Peter Horsfield

This edition first published 2015 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Registered OfficeJohn Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Peter Horsfield to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this title

Hardback: 9781118447376 Paperback: 9781118447383

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover image: © Eddie Gerald / Alamy

For Noah and Audrey

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

What’s this book about?

What do we mean by Christianity?

What do we mean by media?

Media and the historical development of Christianity

Notes

Chapter 1: In the Beginning

The social and media context

Jesus in his media context

Remaking Jesus in speech and performance

Notes

Chapter 2: Making Jesus Gentile

Context: the media world of the Roman Empire

Early Christian writing

Paul and letter writing

The end of the beginning

Notes

Chapter 3: The Gentile Christian Communities

The appeal of Christianity

Multimedia communities

Christian writings

The reception and circulation of Christian writings

Resistance to writing

Notes

Chapter 4: Men of Letters and Creation of “The Church”

The Catholic-Orthodox brand

Tertullian

Cyprian

Origen – the media magnate of Alexandria

Writing out women

Notes

Chapter 5: Christianity and Empire

Imperial patronage and imperial Christianity

Councils, creeds, and canons

Constructing time – Eusebius’

Ecclesiastical History

The scriptures as text and artifact

Notes

Chapter 6: The Latin Translation

Latin roots

After the fall

Monasteries and manuscripts

Written Latin and the consolidation of medieval Christendom

Notes

Chapter 7: Christianity in the East

The Church of the East

Islam

Writing the voice

Regulating the eyes

Notes

Chapter 8: Senses of the Middle Ages

The medieval context

Making time

Seeing space

Rituals and hearing

Nice touch: relics, saints, and pilgrimage

Notes

Chapter 9: The New Millennium

Marketing the Crusades

Scholasticism and universities

Cathedrals

Catholic reform

The Inquisition

Notes

Chapter 10: Reformation

Printing and its precursors

Martin Luther

John Calvin

Reworking the Bible

The changing sensory landscape

Catholic responses

Ignatius of Loyola

Notes

Chapter 11: The Modern World

The legacy of the Reformation

Catholic mission

The impact of print

Evangelical Revivalism

Protestant mission

Notes

Chapter 12: Electrifying Sight and Sound

The technologies of the audiovisual

Christianity and the twentieth-century media world

Mainline mediation

The Evangelical Coalition

Fundamentalism and Pentecostalism

Notes

Chapter 13: The Digital Era

The empire of digital capitalism

Digital practice

Global Pentecostalism

Media and Christian sexual abuse

Tradition and change

Notes

Conclusion

Afterword

Notes

References

Index

EULA

List of Illustrations

Chapter 6

Figure 6.1 The initial page of the Book of Genesis from an illuminated bible produced in the thirteenth century, possibly in Bologna, Italy. The sweeping letter “I” introduces the text “In the beginning,” and the images within it link the creation of Adam visually with the redemption of Christ. Source: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. 107, fol. 4. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Figure 6.2 Caroline miniscule script, developed during the time of Charlemagne, used here in an eleventh-century French manuscript for the first prayer for the second Mass of Christmas day. The legibility of the letters, layout of the text, and ease of reading made it the most common book script for centuries. Source: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig V 1, fol. 8v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Chapter 7

Figure 7.1 Russian icon,

Our Lady of the Great Panagia

, early thirteenth century, at the State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Source: By jimmyweee (Moscow Uploaded by russavia) [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Chapter 8

Figure 8.1 The Reliquary of Mary Magdalene, at the Basilica Church of St. Mary Magdalene, Vézelay, France. The reliquary is supported by a bishop, a king, two angels, a monk, and a queen. Source: By D. Villafruela (own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Chapter 9

Figure 9.1 Canterbury Cathedral, United Kingdom, twelfth century. Source: photo by Adam T. Shreve.

Figure 9.2 Francisco Rizi,

Auto de Fe en la Plaza Mayor de Madrid

, 1683. Source: © Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy.

Chapter 10

Figure 10.1

The Pope Is Adored as an Earthly God

, by Lucas Cranach the Elder, in the 1545 pamphlet of Luther’s

Depiction of the Papacy

. Source: © Germanisches Nationalmuseum. Photo by Monica Runge.

Chapter 11

Figure 11.1 J.G.G., wood engraver,

The Missionary

, wood engraving, 1854, from

The Family Christian Almanac for 1855

. New York: American Tract Society, 1854. Source: photo by David Morgan.

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

1

Pages

xi

xii

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

Acknowledgements

A work that covers more than two decades cannot help but be indebted to many people, not just for distinctive contributions but also for helpful conversations, numerous insights, and “things I should read” gained along the way. As Tennyson has astutely noted, “I am a part of all that I have met.” But there are a number of people who played key roles at key times I wish to acknowledge. Tom Boomershine kickstarted my thinking on the topic again in three days of stimulating conversation in the early 1990s. The women of Shivers gave me new insights and understanding into a side of the church and Christianity I had not fully appreciated before. John Rickard gave me a space to begin to flesh out some of the wider historical issues. I have been very fortunate to be involved in a distinctive international community of supportive scholarly colleagues working in, or building, the emerging field of media, religion, and culture. In particular, thanks to the small group of colleagues I worked with over nine years on the International Study Commission on Media Religion and Culture. A better group of colleagues one could not find, thanks to the individuals, the leadership of Adan Medrano and Stewart Hoover, and the visionary support of the Porticus Foundation in the Netherlands. When I moved to my current university position, Lauren Murray as my Head of School was very supportive of my research in what was then an unusual field for a university school of communication. Grant Roff helped immensely over a lunch one day by clarifying my audience at a key time of the writing. The three anonymous reviewers of the draft, organized by Wiley-Blackwell, provided very useful feedback that informed this final version – as did a number of friends and colleagues who graciously took the time to read the draft and provide valuable feedback and suggestions: Philip Lee, Vanessa Born, Lynn Schofield Clark, Noel Turnbull, and Marilyn Born. Thanks also to Rachael Horsfield for her work in compiling the index.

Sections of chapters 3 and 4 were used in a chapter in Knut Lundby (ed.), Religion across media: from Early Antiquity to Late Modernity (New York: Peter Lang, 2013).

Sections of chapter 6 were used in a chapter in Kennet Granholm, Marcus Moberg, and Sofia Sjö (eds.), Religion, media and social change (New York: Routledge, 2014).

Introduction

The documents and other survivals of the past are dead to us until we ask them a question, until we want to know something from them.

(Benedetto Croce, 1917)

What’s this book about?

Interest has grown in recent decades in how media and religion interact and are connected. This interest has been stimulated by two current phenomena: the global spread and rapid take-up of new media on the one hand, and the reemergence of religion into the public domain as a significant global and cultural force on the other. The concurrence of these two phenomena has prompted people to wonder about whether and how the two are connected.

The interactions between media and religion were studied to some extent through the twentieth century. These studies tended to use a narrow view of media as primarily instruments for carrying messages or information. They also tended to view religion primarily as what was happening in religious institutions. The primary focus therefore was on how religious leaders and institutions used media to communicate their messages.

More recent studies of media and religion have taken a different approach. Working from a more cultural perspective, they view media not as individual instruments of communication but as part of a conglomerate of technological and nontechnological social mediation by which people access and contribute to processes of making meaning in their lives.

This approach also sees religion in broader terms. Rather than focusing on religious institutions, this view sees religion as something that occurs as people work with symbolic resources provided by their culture to create meaning for their daily lives, to share experiences of awe and mystery, to explore new alternative realities, and to manage the anxieties and unfilled possibilities of life.

While significant work has been performed in recent years in studying media and religion from this more cultural perspective, most of the work has lacked a historical dimension as a way of relating what is happening now to what has happened in the past. As a result, a lot of thinking about media and religion sees what is happening today as a distinctly modern issue.

This book provides some of that historical perspective through a focused study of one of the world’s major religions, Christianity, examining the ways in which the processes of communication and technologies of media have conditioned how Christianity has developed historically. The intent is not to provide an encyclopedic description of all the ways in which Christianity has been mediated. It is, rather, to provide a historical survey, setting a framework within which specific instances may be examined in greater detail.

Doing so requires first clarifying some perspectives.

What do we mean by Christianity?

Christianity has its origins in the activities of Jesus, a Middle Eastern Jewish peasant who emerged as a charismatic religious reformer, preacher, teacher, faith healer, and miracle worker in the turbulent eastern Roman region of Galilee and Judea around the period 27–30 CE.

Today that Jewish peasant is revered as the founder and central figure of the global religion of Christianity, an immensely diverse religion whose adherents and followers make up around a third of the current world’s population. Its members include Nobel laureates and uneducated peasants, high-income urban professionals living in the richest cities of the world and poor rural workers in the poorest countries of the world, the literate and illiterate, lawmakers and lawbreakers. The name “Christian” has been applied equally to people living within the feudalism of the Dark Ages and people living in today’s globalized, technological world. Being Christian has been claimed by soldiers and pacifists, dominators and dominated, leaders who have sacrificed their lives for the defenseless and leaders who have slaughtered the defenseless.

Ask Christians what Christianity is, and you will get a multitude of definitions and opinions: someone who belongs to a church; someone who believes in particular doctrines such as the Trinity or salvation; someone who participates in Christian rites; someone who is kind, forgiving, or loving in nature; someone who has particular moral standards or behaviors, such as being honest or sexually “pure”; someone who lives in a Christian country; or someone who has had a particular emotional, spiritual, or psychic experience such as being born again or speaking in tongues. How do we chart our way through such a complex forest of opinion?

In a similar way, ask followers of Christianity for a coherent picture of who Jesus was, and you will find not one single historical account but an infinite mélange of opinions, based not only on the Bible but also on impressions gained through Christmas carols, cultural festivals, hymns, prayers, children’s storybooks, Sunday School lessons, sermons, theological books, popular devotional guides, statues, paintings, and the movies. While Jesus has been the inspiration for many to live self-sacrificial lives in service of others, he has also been the justification for others to commit mass murder or extensive sexual abuse of children. While he’s been the motivation for many to give away their wealth and possessions and live exemplary lives of voluntary poverty, he has also been the justification for Christians to take money from the poor to pay for excessive lifestyles or build opulent buildings. In my lifetime, Jesus has been presented variously as a first-century countercultural simple-living hippie, a radical social justice iconoclast, a gentle and caring religious teacher, a spiritual healer, a champion of the poor and outcast, an avenging and punishing lord of the universe, a self-sacrificing savior of the world, and the transcendent facilitator of modern capitalist prosperity and the urban lifestyle.

As if that wasn’t enough confusion, within and between each of these standpoints is immense diversity. Bitter arguments have broken out, and tens if not hundreds of thousands of Christians have been killed, in the process of Christian groups fighting with other Christian groups to have their views accepted as “the” exclusive truth about Christianity. The history of Christianity is a history of someone or some group using force and their power to draw a line on who is included in Christianity and who isn’t.

This diversity of opinions and perspectives points to the fact that Christianity is far more than just a repetition or reproduction of the message of Jesus. It has been a complex and expanding mediated phenomenon, a constant creative reproduction and rhetorical reworking of Jesus to match the conditions of an ever-expanding set of constantly changing circumstances. In the process, as Marianne Sawicki has noted also of the first century, the figure of Jesus has been conscripted to say and do things that likely would have astounded the Jew from Nazareth.1

In the religion of Christianity, Jesus the Middle Eastern peasant has been transformed into the most powerful and fecund reservoir of media resources the world has seen: snippets of history, biographies, stories, heroes, heroines, villains, personal testimony, libraries, cultural interpretations, philosophical speculations, artifacts, ritual practices, visual imagery, sensory experiences, nations, rule books, ethical systems, architectural constructions, and traditions of organizational structure and process. That reservoir of media resources makes Christianity capable of immense adaptability. Drawing from these historical media resources gives the appearance of continuity with the past while at the same time an immense capacity for regeneration and invention. It’s left to your judgment and your personal view to decide whether Jesus himself would have been happy with what has been done to him.

Because of this immense complexity in the concept of Christianity, in this study I take a deliberately broad view of what Christianity is. My working definition is:

Christianity is those activities, practices, ideas, artifacts, groups, and institutions that identify themselves, or may be identified with, the broad historical movement associated with the figure of Jesus.

I take such a broad view for a number of reasons that are important. One is that there have been continual struggles and conflicts to reduce the existing diversity to suit the needs and reinforce the power of particular groups over others. Understanding why such conflicts occurred and the factors that influenced them is more likely to be achieved by working with as broad a view of Christianity as possible.

A second is that media have often played an important part in these conflicts. Many of the fights in Christianity have either involved different uses of media or been about whether particular media are Christian or not. These sorts of media conflicts will be more identifiable if we follow as broad a view of Christianity as possible, rather than be restricted by a narrower definition established by the winners.

What do we mean by media?

The second critical issue to address is what is meant by “media.” How one thinks about media can prejudge our conclusions by forcing thinking in one direction and missing others. Two common preconceptions about media need to be discussed to undertake a historical study such as this.

One is the assumption that media are primarily modern technological forms of communication, such as radio, television, the internet, mobile phones, social media, and so on. Thinking about media in this way suggests that questions about the interaction of media and Christianity are recent questions only. From a historical perspective, however, what is happening today with “new media” is consistent with the way in which Christianity through the centuries has continually defined and redefined itself within the demands and opportunities of available cultural processes and technologies of mediation.

The second dominant preconception is that media are to be understood just as technological instruments for carrying information or messages. This modern view, commonly called the “instrumental view” of media, has a strong focus on studying how media technologies and techniques could be used to produce particular outcomes, particularly in areas like advertising and marketing, corporate communications, politics, and even evangelism. But it is too restricted a concept for understanding the interaction of personal, social, cultural, political, and technological factors that come into play when people interact with each other and with their environments to survive, progress, and make life meaningful.

The wider view being taken in this study is that social reality itself is a mediated phenomenon, a communication ecology in which individual and social exchanges take place within a social matrix that is already rich in communicative materials such as traditions, material practices, symbols, artifacts, technologies and techniques, institutional structures, and patterns of relationship. To understand media, then, one needs to look not simply at individual media technologies but also at the cultural contexts in which these have emerged and to which they contribute. This includes nontechnological and bodily aspects of communication and their cultural significance.

For that reason, this book addresses a wide variety of mediated communication: the numerous styles and uses of oral communication; written text such as scriptures, different genres of religious writing, correspondence, signage, and archival libraries; visual media such as painted images, statues, decorations, symbols, illustrations, photographs, and moving pictures; material forms of communication such as prayer beads, bread and wine, buildings, and landscapes; tactile forms of communication such as physical greetings, kissing, the use of water or smell, and the feel of artifacts; sounds such as chanting, singing, intoning, and bell ringing; as well as technologically based media such as print, television, radio, telephone, and computer-based digital technologies of communication.

To chart a course through this complexity, in this study I will draw on a number of perspectives on media to give some focus to the analysis.

Although all media are different, in practice they draw on and interact with each other. On the one hand, each medium has particular ways of operating, sometimes called “affordances” or “liberties of action,” that give them relative advantages for enabling or doing particular things more effectively than other media. It is these affordances and their relevance to the needs of a particular society that give a medium its social power and capital. On the other hand, both historically and today, people generally live in and move quite freely around layered media environments, integrating a variety of media and communication practices as they go about their daily lives. Media can also create their own layered environments within a marketplace, with different media performing particular functions that integrate in a complementary but continually changing way with others.

Along with the particular uses that are made of them, the technological and social characteristics of different media can be influential in shaping wider social perceptions, practices, and values. Walter Ong

2

proposes three particular characteristics of media that can be effective in this way. One is the different physical senses that are addressed and activated by a particular medium and the consequences these have for social perception and bodily participation. A second is how a medium facilitates the storage, retrieval, and reproduction of information, which has important consequences for how cultures form thought, analyze, and build systems of meaning. The third is how a particular medium sets people in relation to each other, and the influence that has on how relationships and patterns of authority are formed. The influences exerted by these technological, social, or sensory characteristics of a medium are generally subtle and subconscious, but they can also be profound and extensive. These will be explored further throughout the book.

Media exist as part of a wider structure of social, economic, and political orders, and these orders influence the shape that a medium takes and the social functions it performs. This is particularly noticeable in relation to media industries. Any medium of communication generally requires a range of supporting social structures and practices in order to function. These include shared language or literacy skills appropriate to the medium, educational systems to teach those language skills, the development of technical skills to use the medium to produce and receive content, social and economic infrastructure to supply the materials necessary for the medium to work, and legal regulations and policy structures to manage it. Even a simple medium like a written letter can’t be used if there are no pen, ink, and paper to write with, no way for the letter to be carried, and no people with the literacy skills to write the letter and read it when it gets there. Having the resources to access all of these requirements is a crucial factor in accessing the advantages and power that a medium brings. As will become apparent in this study, the abilities of particular Christian institutions or leaders to adapt their message or practices to available media industries and to establish their own media industries have been important factors in some of the major shifts that have taken place within Christianity since its earliest days.

Media are intimately connected with language, and a study of the interaction of media and Christianity cannot take place without also considering language. Because one of the only ways we can understand the world is through its representation to us in verbal or visual language, the constructs of language are important elements in the production of religious meaning. From this perspective, language is more than just an agreed, functional arrangement of grammar and vocabulary by which people talk to each other; it is a crucial arena in which struggles for power take place over such things as whose reality is represented in language and whose isn’t, how different languages construct reality differently, whose language practices are recognized as competent and authoritative and whose aren’t, who has the competency and legitimacy to speak and under what circumstances and who doesn’t, what hierarchies of communication and language practice and power exist and what practices reinforce those hierarchies, who has the ability to command attention and who doesn’t, and in what ways particular language practices reflect and constitute the patterns of social power within the wider culture.

3

Different media may contribute to this by giving preference to particular forms and uses of language and their language groups over others.

It is apparent, then, that media need to be approached and analyzed, not just from an atomistic way that looks at individual situations of communication but also as a holistic cultural matrix that forms around patterns of mediation, including groups and traditions of practice, patterns of production and consumption, protocols of power and authority, political associations, sources of identity, hierarchies of technical competencies, shared sensory expectations, and protocols of performance, experimentation, and change.4

Studying Christianity through the lens of cultural practices of media opens up a number of avenues for rethinking Christianity. Rather than accepting the hegemonic or so-called orthodox view that Christianity is a relatively coherent, structured, harmonious singular phenomenon, it suggests that Christianity needs to be looked at as a diversity of different cultural groups that are continually contending with each other in the process of making sense of and living out their particular religious identity. It also opens the scope to investigate how the different ways in which Christian groups communicate have shaped their Christian identity and informed their sense of difference.

Media and the historical development of Christianity

In line with the perspectives outlined in this Introduction, in this book Christianity will be looked at not just as an institution or religion that uses media, but also as a mediated phenomenon in itself: a phenomenon that has developed and been constructed in the processes of being communicated.

The following questions will be explored: How have all the mediational practices from within and outside Christianity interacted with each other and shaped what Christianity has become? How have the different practices of mediation used within Christianity supported, subverted, or negotiated with each other? In what ways have other traditions of communication been taken up and used to form different traditions within the religion? How have the groups associated with those different traditions and cultures cooperated or competed with each other?

As this book pursues these questions, a number of emphases will become apparent:

Media and Christianity will be studied not as separate domains but as symbiotic cultural phenomena that inform and are integral to each other. Christianity is a mediated phenomenon; there is no aspect of Christianity that can exist except as it is being communicated. At every step of the way, how it communicates itself becomes an indistinguishable part of what Christianity is, whether that communication be through oral speech and physical performance, silence, smells, writing, physical phenomena, visual artifacts, song and dance, printing, architecture, or electronic media.

The meanings of Christianity are to be found not just in what is presented in official texts and by official representatives or institutions, but also in the ideas and practices of common people, whether they agree or disagree with the official versions. The extent to which these common opinions can be accessed is precarious, as most of the resources that have been preserved reflect the viewpoints of those who had power to preserve their records and destroy others. But attempting to do so is important.

The truths of Christianity are not unconditioned revelations or disinterested receptions from God. Christian views of reality and concepts of truth and meaning, including statements about a transcendent God, are human constructions. They commonly emerge from the desire or need to build meaning into materialistic experiences and then identify those constructed meanings as being inherent in the experience. When the element of vested power is introduced into the analysis of Christianity, it challenges claims by particular groups that they alone represent or are concerned for the integrity of the religion.

This book seeks to take seriously the diversity of positions, practices, and phenomena that has characterized Christianity and media through the centuries, although not all of these, of course, can be dealt with. It is only by considering the widest diversity of phenomena possible that one can get a better idea of the forces and factors that have narrowed it down to particular emphases or orthodoxies, and the part that media have played in that narrowing (or broadening) process.

This book questions the idea that Christianity has a single defining essence. The diversity of Christianity, and the inescapable contradictions within it, means that coming to a conclusion about a core essence can only be done by one group of Christians denying legitimacy to the sincerely held beliefs of others. As noted in this Introduction, Christianity is perhaps best understood as a repository of beliefs, practices, and media resources accumulated through its history that living people and groups constantly draw on to remake their view of Christianity in a way that is relevant for constantly changing circumstances.

The risk in a study such as this is that it is attempting something so broad that it could founder on the discrepancies of particulars. Any study of media and Christianity is investigating two huge phenomena that in themselves encompass most of life and human experience. It is likely to be open at every page to criticism by specialists who know the specifics of particular areas more than I ever will, although if it stimulates such an exchange it would have achieved a good purpose.

Questions also may be raised about the appropriateness of applying a modern concept such as media retrospectively to historical events and phenomena that occurred when people didn’t even know the term. Can judgments be made about past phenomena on the basis of perspectives that are principally relevant today? I think they can. In fact, most historical studies choose specific topics, periods, or issues to investigate, not only because they are interesting in their own historical terms but also because looking back through the lens of the present can give us insights by which to better understand our own situations.

But the study has a particular context that justifies these risks. It arises at a historical point when, at the same time that there are major changes taking place in the global structures of media, there are also major changes taking place in the global structures and practices of Christianity. This book reflects a growing view that these significant changes in Christianity today are closely connected to changes taking place in new technologies, cultures, and global structures of media. However, it takes that connection further by proposing not only that media and Christianity are connected today, but also that they have always been connected. What we are seeing today is not just a late modern phenomenon, but another instance of a restructuring of Christianity on macro and micro levels, stimulated by and related significantly to major changes in the fundamental structures of socially mediated communication.

NOTES

1

Sawicki, 1994, pp. 85–86.

2

Ong, 1967, 1982.

3

For further insights on this, see Bourdieu, 1977; Lewis, 2005.

4

Couldry proposes a practice approach to the study of media that starts “not with media texts or media institutions but from media-related practice in all its looseness and openness. It asks quite simply:

what are people

(individuals, groups, institutions)

doing in relation to media

across a whole range of situations and contexts” (Couldry, 2012, p. 37).

1In the Beginning

Investigating who Jesus was and how Christianity began is a media phenomenon in itself. It is difficult now to distill the original figure of Jesus from the memories, recollections, accumulations, inventions, myths, and interpretations that have become part of the Christian mediation of him, even in its earliest documents.1 For some, getting a reasonable historical picture of Jesus is either not possible, not important, or not a question. But there’s value in attempting to do so, in order to get at least an approximation of what was there in the beginning, as a basis for understanding how and why it’s changed and which factors influenced the changes.

What has commonly been known about the history of Jesus and the beginning of Christianity comes from copies of copies of a relatively small number of written documents reproduced in what is now called the New Testament, comprising four Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, and a number of letters. But these texts have particular characteristics that need to be considered in building an accurate picture.

One is that they did not begin to be written or compiled until at least twenty years after Jesus had been killed and a post-Jesus movement was underway. Although significant weight is given by many scholars to the dependability of the preservation of the events of Jesus in a Christian oral tradition,2 much had happened in those intervening decades and there is evidence that some of those later events and the ideas that came out of them were taken up and included in the writing about Jesus as if they were part of Jesus’ own story.

A second is that these key documents in the New Testament are just a few of a much larger number of documents also written about the same events. This larger corpus of documents were culled over a period of several hundred years in an ideological process of selection to create an authorized version of the history (a canon) that reflected the interests of those in power at the time. Many of those other documents, which offered alternative viewpoints, were destroyed in what we would now call a process of media censorship and control.

A further consideration is that these few select documents are nothing like what we would call objective or balanced historical recording. They are partisan, creative, retrospective, interpreted reconstructions of something that happened several decades earlier by a passionate social minority group with a vested interest. Borg identifies them as testimony rather than what we understand as history, and they should be read therefore for their meaning and not primarily for their factuality.3

A final consideration is that the texts are a specific medium – writing. Although almost all of the earliest Christians were illiterate, the perspectives we have today on who Jesus was and what he did are the views of an unrepresentative group of literate Christians who made up less than 5% of the Christian community at the time.

There has been a significant scholarly interest from the start of the twentieth century to apply modern historical critical methods to these writings to try to separate out the more historical aspects of Jesus from later inventions and accumulations, in order to locate Jesus more accurately within the social, cultural, and religious milieus of his time. Some of the findings of this research have been controversial and in many cases contradict orthodox Christian beliefs. Many are still being debated.4 Rather than one conclusion, at best what has been reached are a number of possible options, with Jesus being portrayed variously as a peasant sage, a social revolutionary, a religious mystic, a prophet of the end time, a marginal Jew, or the true Messiah.5

It is beyond the scope of this work to try to resolve issues that are unresolved by highly qualified biblical scholars. However, this body of research offers valuable insights that can be useful in getting a clearer picture of what Jesus may have thought and what he was doing. As Borg notes, Jesus ceases to be a credible figure and loses his humanness if attributes properly belonging to his followers after his death are ascribed to him before his death – it is “neither good history nor good theology.”6 Since the field is still a hotly contested one, what follows is my educated reading of that recent thinking compiled to give us a framework for understanding Jesus’ thought and practice, and for reconsidering the development of thought and practice that followed him and the place of media in those developments.

The social and media context

Jesus was born and spent much of his life in the ancient Roman Middle Eastern region of Galilee. Because of its position on the trade routes between Asia Minor and Egypt, for more than a thousand years, the wider area of Palestine had negotiated its religious and political identity amid constant imperial occupations and cultural colonization. At the time of Jesus it was part of the Roman Empire, governed by rulers appointed by Rome according to Roman policy.

The Jewish society into which Jesus was born was diverse and highly stratified socially, economically, and religiously. Communication patterns and practices reflected and reinforced these class distinctions. The languages one spoke, the circumstances in which they were spoken, how they were spoken, whether one was literate in a particular language or another, and the extent of one’s literacy were all markers of a person’s or group’s identity and place within the local and imperial cultural hierarchies. Three languages in particular were important in social positioning and stratification. Greek was the dominant language used in urban areas in business, international politics, and secular culture. Hebrew was the language of Jewish scriptures, and it was used primarily in the Temple and Jewish religious literature and practice. Its restricted use and literacy had led to the development of a religious leadership class based primarily on their capacity and resources to read and speak Hebrew. Aramaic, which had a number of dialects, was the common and most widely used language in general discourse and village life.

Levels of literacy were low and generally restricted to the upper classes. While there is a variety of opinions about levels of literacy, the estimation is that from 95 to 97 percent of the population were illiterate,7 meaning that interactions of social and religious life, particularly in the towns and rural areas, were almost wholly oral in character.

Despite the general low levels of literacy, the religion of Jesus was a blended oral and literate religious culture. For hundreds of years, the Jews in Exile, in Israel, and in the Diaspora had been assembling and reproducing written scriptures and other texts. Protocols had been developed for how these written documents were to be integrated into worship, teaching, and wider oral practices of the religion. Different Jewish religious groups were marked not only by differences in their religious and cultural views, but also by different traditions of the integration of text into oral practice. These included the Sadducees, the hereditary priestly families and landholding aristocrats of Jerusalem; the Pharisees, a religious group marked by their piety born of struggles against secularizing trends a century earlier; the Scribes, a literate group who played a powerful role interpreting the written texts of the religion; and the Essenes, an apocalyptic sect and monastic community of Judaism.

For those living outside Jerusalem or without access to the Temple, the center of religious community was the local synagogue, a primarily lay-oriented community that stressed reading or recitation of the Hebrew scriptures, exposition of the scriptures when there was a person present who could do it, singing of hymns, and offering of prayers. Although illiterate, most heard the scriptures spoken sufficiently frequently to be able to recite significant portions of them from memory. Since most village people spoke Aramaic, a practice developed of providing oral Aramaic interpretations and applications of the Hebrew scripture readings, known as targums. When the Jerusalem Temple was destroyed in 70 CE, the synagogue form of worship with its combination of reading or reciting scriptures with oral commentary and debate became the common form of worship in reformed Rabbinic Judaism. In its early development, Christian communities drew significantly on this media model in the development of Christian worship practice.

A major issue in people’s daily lives was making enough not only to provide the basic necessities of life but also to meet the financial burden of taxation. The Romans imposed heavy taxes, tolls, and tributes on occupied populations to support their imperial activities, the military, and the ruling elite. Depending on occupation and location, these imperial tax obligations could range from 12% to 50%.8 Collection of taxes was leased out by the Romans to the local upper stratum, including religious leaders, who added to the imperial tax obligation their own costs and profits. These were ruthlessly collected, with military support provided to local tax collectors if needed. Jews were also obligated to pay religious tithes and taxes, specified in the Torah as part of the Covenant, for the support of the temple, its priests, and the poor. For farmers, the combined Jewish and Roman taxes were around 35 percent.9

For those living already at a marginal or subsistence level, meeting these obligatory taxes was crippling. In an empire that was dominantly agricultural, income and wealth were tied significantly to ownership of land. Those whose traditional or inherited land was not large or fruitful enough to support their family and meet their tax obligations eventually were driven into debt, were forced to sell their land to the upper classes, and became either a worker for others or even a slave in what Stegemann and Stegemann describe as “a regular process of pauperization.”10 Increasingly, the ownership of land and therefore wealth became concentrated and restricted to the upper classes.

Many coped by paying the Roman taxes, which were ruthlessly enforced, but not the religious ones, which lacked the same power of enforcement. In this situation, the only sanction the religious leaders could impose in the face of this loss of their income was to declare those who did not pay their religious dues to be ritually unclean and therefore excluded from religious participation until the taxes were paid.

This economic impact was felt particularly in the subsistence economy of the rural towns and small villages, and it led to a significant underclass – “a growing number of landless laborers, widespread emigration, and a social class of robbers and beggars.”11 The social disruption it caused produced numerous apocalyptic figures and movements – prophets, preachers, and messiahs – who traversed first-century Palestine proclaiming the day of God’s judgment and the end of the world.12

This was the world Jesus grew up in.

Jesus in his media context

According to the Christian written tradition, Jesus grew up in Nazareth, a village in Galilee less than four miles away from a large urban center, Sepphoris. Prior to his religious ministry, he is identified as a carpenter (tekto¯n) and son of a carpenter.

These rural roots and manual occupation are indicators of Jesus’ cultural and economic position. Geographically, coming from Nazareth associated him with an inconsequential part of the country. When it was recommended to the cultured and Greek-speaking Nathanael that he meet Jesus, Nathanael’s response was “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?”13

Jesus’ spoken language was a Galilean dialect of Aramaic, an identifiable accent and manner of speech that likewise were disdained by the religious elite and urban dwellers.14 As a carpenter servicing different customers, including possibly in the nearby city of Sepphoris, Jesus may have had some knowledge also of Greek, Latin, and Hebrew words.

His identified occupation as a carpenter also locates Jesus socially. Although some modern interpretations romanticize him as a skilled specialist tradesman, the term was an occupational designation of a construction worker who could be a “mason, carpenter, cartwright, and joiner all in one.”15 The term “carpenter” was also a derogatory cultural signifier for the illiterate lower classes.

His birthplace and occupation therefore locate Jesus within the lowest, most vulnerable stratum of society, associated with small farmers, tenants, traders, day laborers, fishermen, shepherds, widows, orphans, prostitutes, beggars, and bandits. His people and family were people who were relatively poor if not absolutely poor, living at a subsistence level and constantly struggling for the basic necessities needed for survival.16 This class stigmatization explains the reported response from people when Jesus began speaking publicly in his hometown: “‘Where did this man get this wisdom and these deeds of power? Is not this the carpenter’s son?’ … And they took offense at him.”17

Based on this background, it is also likely that, like others of his class, Jesus was illiterate. This likelihood goes against the largely unquestioned traditional Christian view that Jesus was naturally able to read and write. Unpacking this contradiction is important from a media perspective.

One of the grounds for the assumption that Jesus was able to read and write is a number of places in the Gospels where Jesus is referred to as reading and writing.18 Some scholars argue that a Jewish boy of Jesus’ time would have learned to read and write as part of his religious participation,19 or that Jesus could not have expressed many of the sayings he did without a detailed knowledge of the texts of “The Law and the Prophets.”20 Later theological construction of Jesus as the Son of God also cast him as capable of superior human qualities and therefore at least equal to the abilities of the social elite.

However, Crossan argues a strong case that in a situation where 95 to 97 percent of the Jewish state was illiterate and where Jesus was a member of the lowest class in the society, it must be presumed that Jesus was illiterate.21 Dunn likewise contends, “We have to assume, therefore, that the great majority of Jesus’ first disciples would have been functionally illiterate. That Jesus himself was literate cannot simply be assumed.”22 The reason why Jesus’ lower-class illiteracy was downplayed or changed in later writings about him has media relevance. Crossan suggests that Jesus’ illiteracy posed a problem to later educated and literate Gentile Christians who wanted to commend the Christian faith to the cultured members of their own class, and they did so by writing it out in the writing of their stories. The later written accounts of Jesus as a young man debating the learned teachers in the temple and personally reading and interpreting a passage from Isaiah in the Nazareth synagogue both come from Luke’s Gospel, the author of which was an educated physician living in Rome. Crossan sees them as later textual reworkings of Jesus to make him more culturally acceptable to the media culture of a different class. Accounts of Jesus reading and writing, he advocates, are “Lukan propaganda rephrasing Jesus’ oral challenge and charisma in terms of scribal literacy and exegesis.”23

Recognizing Jesus as illiterate does not contradict his frequent quoting of Jewish sayings and excerpts from scripture in his teachings, but locates them rather within the oral cultural practice of his time. It was a common and a significant skill of illiterate people to be able to recite significant passages of scripture from memory as a result of hearing them read frequently or being taught them. Through these oral practices, Jesus and most of his Jewish contemporaries would have known the foundational narratives, basic stories, and general expectations of his tradition and be able to use and quote them in communication and argument. How this was done, however, was distinctly oral in character and quite different from “the exact texts, precise citations, or intricate arguments of its scribal elites.”24

While not a critical issue, considering the likelihood that Jesus was probably illiterate is important for a number of reasons. It recovers significant class and political dimensions in his religious message that were subsequently written out. It embeds his highly skilled oral charisma in his lower-class background rather than as a developed skill of a cultural elite. It also gives an insight into one of the early transformations of Jesus by followers who inhabited a differently mediated culture and wanted to make Jesus relevant to that culture. In this process, however, the distinctive claim of the lower classes for Jesus to have been one of them was taken away by a minority group of Christian writers. This concern would reemerge later in challenges to Christian writing. Because of the permanence of writing and the censorship of alternative views, however, the Lukan view that Jesus was literate would become unquestionably embedded in the Christian tradition.

As an adult, Jesus became a follower of the itinerant prophet, John the Baptist, before becoming a charismatic teacher himself. He gathered around him an inner band of disciples and other men and women who joined him in his travels and supported and helped him in his healing and miracle work. It was to this group primarily that Jesus passed on verbally his religious and social vision and teachings. It is noteworthy that the people he chose as his inner band were primarily members of his own class and subject to the same bitter poverty to which Jesus’ religious message was addressed. Understanding this class reality gives a more realist insight into a number of incidents reported in the New Testament Gospels that are frequently spiritualized or allegorized. Jesus’ many references to the poor and hungry and promises that in the coming Kingdom of God they will be fed are frequently interpreted as spiritual hunger, rather than seen for what they literally are: a political manifesto to the poor and starving that, in the coming Kingdom of God, they will have food to eat.

The activities of Jesus as they are recorded reflect two identifiable religious communication genres from within the Jewish tradition that carried cultural meaning for his audiences. His effectiveness as a communicator lies in his skill in activating and challenging the nuances of these cultural literacies.

One was that of the oral prophet, a recognized figure combining oral traditions of speech as charismatic, dramatic, and demonstrative performance. The identification of Jesus with this cultural genre is indicated in questions asked of Jesus’ disciples on occasion if he was one of the revered Jewish prophets come back. Jewish prophets were largely rural-based critics that forthrightly addressed current public issues of political, social, and religious importance, particularly the oppressive effects of the urban religious government on the rural poor. Within the prophet’s message was an emphasis on God’s defense and vindication of the oppressed, a critique of the dominant systems of power and the power-holders causing the oppression, and the vision of a new age to come in which the present system of injustice is overcome, all of which can be seen in Jesus’ message. 25

The other communication genre reflected in Jesus’ communication was that of the sage or wise teacher within the rabbinic tradition. Like most rabbis, Jesus gathered around him a group of identified disciples who travelled with him and assisted him in his work, and to whom he directed and entrusted his teaching.26 On one occasion, Jesus sent out his disciples in pairs to proclaim more widely the good news he was bringing, something that Thiessen sees as an innovation among rabbis, and a means of mass communication of his message in an oral society, comparable to the coins and inscriptions of rulers.27 This sending out of his disciples became an important signifier in later Christianity and was an important element in concepts of Christian mission.

One of the enduring characteristics of Jesus from a media or communication perspective is his outstanding skill and reputation as an oral communicator and charismatic performer. As Crossan describes him, he was “an illiterate peasant, but with an oral brilliance that few of those trained in literate and scribal disciplines can ever attain.”28 The oral characteristics of his communication had political significance for his audiences. They affirmed the dispossessed, disenfranchised, and illiterate rural and peasant classes and the value of their religious experience and culture in ways they could readily identify with, feel enfranchised by, and respond to. The popular appeal of Jesus can be understood within this context: his identification with his audience, his audience’s identification of his shared cultural rootedness, and his outstanding skill in performing his message within the recognizable genres, relationships, responses, codes, tropes, and expectations of the highly developed oral culture from which he came and to which he spoke. Two genres of oral proclamation are particularly notable and have become emblematic of Jesus’ teaching style: his short sayings or aphorisms, and his parabolic stories.

Numerous examples can be given of the terseness, parallelism, and rhythm of his teaching sayings, characteristics that facilitate memory and oral repetition even to the present time:

Do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will bring worries of its own.

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

Ask, and it will be given you; search, and you will find; knock, and the door will be opened for you.29

The skillfully constructed, memorable, cryptic, and often subversive character of Jesus’ parabolic stories similarly explains their durability and generative power. Well-known parables such as The Lost Sheep, The Good Samaritan, and The Prodigal Son have a strong realism, are concise and economic in their narrative, have memorable and at times subversive characters, are dramatic in their reversals, and frequently have either a twist in the tail that upends audience expectations or a lack of closure that requires hearers to construct their own meaning. Bailey notes that they reflect characteristics still found in “Oriental storytelling”:

I discovered that the Oriental storyteller has a ‘grand piano’ on which he plays. The piano is built of the attitudes, relationships, responses and value judgments that are known and stylized in Middle Eastern peasant society. Everybody knows how everybody is expected to act in any given situation. The storyteller interrupts the established pattern of behavior to introduce his irony, his surprises, his humor, and his climaxes. If we are not attuned to those same attitudes, relationships, responses, and value judgments, we do not hear the music of the piano.30

These multiple layers, nuances, resonances, sharp provocations, and controversial advocacy that mark Jesus’ parables are largely lost to the modern audience, but would have engaged the minds and emotions of his audiences and stimulated discussion among hearers for days.31 Christian leaders, theologians, and preachers frequently try to shut down this polysemy of the parables by giving “definitive” interpretations of their meaning within their own constructed theological systems. Freed from that constraining orthodoxy, however, the parables of Jesus remain even today as questions inviting an answer, and as an encouragement to audiences to participate by generating their own new meaning in the story.

The ordered nature of the documentary records of Jesus’ teachings and stories does not give the full picture of how they were produced or received. Each of the Gospels tells the sayings and parables only once. The Gospel of Matthew, for example, groups together a large number of sayings in what is now a well-known section commonly called The Sermon on the Mount,32 as if all were given on the one occasion. Other Gospels reproduce the sayings in different narrative settings. Dunn suggests that this ordering may reflect the practices of the early Christian oral tradition of preserving the tradition in blocks and series to facilitate memory.33 In practice, though, as with other itinerant teachers, the sayings and stories would have been part of a repertoire of themes and topics that Jesus creatively retold in different settings in response to specific situations or questions.

In addition to his spoken words, he also performed his key messages. He gained some notoriety by assembling a questionable group of people into a new “kingdom community” that travelled with him. Against convention, he mixed with and shared hospitality with women and others designated as social outcasts, and included social nobodies and outcasts as protagonists and exemplars in his teachings and parabolic stories.