Table of Contents

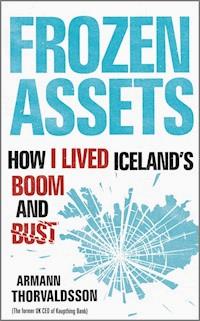

Title Page

Copyright Page

Preface

Chapter One - A Catalyst is Born

Chapter Two - The Financial Caterpillar

Chapter Three - Rattling the Cage

Chapter Four - The Grand Master Syndrome

Chapter Five - Empire-Building

Chapter Six - Where Does the Money Come From?!

Chapter Seven - London Calling

Chapter Eight - The Champagne Island

Chapter Nine - The Beginning of the End

Chapter Ten - The Perfect Storm

Monday 15 September 2008, London

Friday 26 September 2008, London

Monday 29 September 2008, London

Tuesday 30 September 2008, London

Thursday 2 October 2008, the FSA, Canary Wharf, London

Friday 3 October 2008, London

Sunday 5 October 2008, Reykjavik

Monday 6 October 2008, London

Monday 6 October 2008, Reykjavik

Tuesday 7 October 2008, London

Wednesday 8 October 2008, London

Chapter Eleven - The Hangover

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Index

This edition first published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd in 2009 © 2009 Armann Thorvaldsson

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ , United Kingdom

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-470-74954-8

Set in 10.5pt Janson by Sparks, Oxford – www.sparkspublishing.com

Preface

Wednesday 8 October 2008, 10 a.m., Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander, London

In the cafeteria, I was talking to one of the girls from the Treasury desk. Half-heartedly, I was trying to explain our survival chances. Then I noticed that she was looking past me, started to shake uncontrollably and I saw tears streaming down her face. When I turned around, I saw why. Blazoned across the Bloomberg TV screen was the screaming headline ‘Kaupthing collapses’. Shortly after, in a live broadcast from parliament, Alistair Darling, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, announced that he had sold the Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander deposits to ING Direct. He further said he had placed the bank into administration.

As the CEO of Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander (KSF), the news came as a slap in the face. Like everyone else, I knew there were difficulties, but had never been part of discussions with ING, or any other bank, about selling our deposits. The Treasury had invoked a law drafted in the aftermath of the collapse of Northern Rock in 2007, allowing them to remove the deposit base of any bank and replace it with a claim from the Treasury. I knew, though, that no law should have allowed Darling to place KSF in administration without my knowledge. In fact, we were still in discussions with the UK Financial Services Authority (FSA).

Glitnir, another leading Icelandic bank, had been clumsily nationalised a week earlier, precipitating a week of sleepless nights. Gradually but steadily, this had diminished confidence in the Icelandic banking sector – our funding base began to melt away. Over that weekend, we had worked hard on a detailed plan to shrink the business and generate the liquidity we so badly needed.

That Monday, we needed a decent market; a strong headwind. What we got was one of the worst days in the history of the London Stock Exchange. The FTSE index dropped by eight percent. We needed a signal of strong support from the Icelandic government. What we got was an address from the Icelandic Prime Minister announcing that an emergency law had been enacted, subordinating bondholders to depositors. The Prime Minister ended his address with ‘God Bless Iceland’. So much for strength.

With both Glitnir and Landsbanki (the other major Icelandic banks) under the administration of the Icelandic FSA, the UK government used anti-terror laws to freeze the assets of Landsbanki in the UK. A fight started to brew over Landsbanki’s Icesave deposit scheme, resulting in UK Icesave depositors being unable to access their funds. Icesave was the closest comparable product to our internet deposit accounts

– Kaupthing Edge. This was bad news. The media coverage talked constantly of ‘the Icelandic banks’ – tarring us all with the same brush.

Almost all counterparties cut their lines to KSF. Then, that most dreaded event – a run on the bank. In a week, close to £1 billion evaporated. Under pressure, we managed to sell some assets and draw on lines with the parent bank. Further money from Iceland was being discussed when the ING deal with the Treasury was announced that Wednesday morning.

As the news flashed across the Bloomberg screen, I called my contact at the FSA in Canary Wharf. She seemed surprised. A few minutes later, she called back to tell me this wasn’t right. If only the parent company back in Iceland could come up with £300 million more liquidity, we would still be a going concern. But the writing was on the wall. Darling’s announcement made sure that Iceland wouldn’t send any money, and that there would be an even greater run on the deposits. It was all over.

I sat alone at my desk, staring at the computer screen. I felt shattered. I had staggered on for a week, sleeping just a few hours each night, now I was running on empty. It was difficult to sort out the feelings. Years of work building up a business had come to an end. Hundreds of people would lose their jobs. People who had trusted us with their money would lose a part of it – how much I couldn’t tell at the time.

But then the failure of KSF in the UK was almost overshadowed by the fact that Kaupthing as a whole had fallen. I had spent even more time, almost 15 years, building it with my colleagues and friends. Still, the failure of one bank seemed minor, compared to the fact that my country was in ruins.

I started to think about how all this had all happened. How Iceland – a tiny nation in the Atlantic – rose to the heights of international finance; how I was involved; and how and where it all went wrong. We had built up a bank from a floor of an office block in Reykjavik to beautiful offices in the world’s financial capitals; from being worth less than $4 million to a market capitalisation of over $10 billion. We had travelled the world, changed the face of the high street and rubbed shoulders with celebrities.

I left the Kaupthing Singer & Friedlander building in Mayfair, and stepped into my chauffeur-driven car for the last time. I couldn’t help but think back to when it had all started, and how my entrance at Kaupthing contrasted with my exit.

Chapter One

A Catalyst is Born

I had just turned 26 years old when I first arrived at the Kaupthing building in my Russian Lada, in the bitter snows of Boxing Day 1994. It wasn’t a graceful entrance. My passenger door was held together by a piece of string, the temperature controls did the opposite of what you asked them and you had to switch the headlights on to get the windscreen wipers to work. I had bought it with money scraped together by organising a book market with a friend after six months of unemployment. I still remember the smell of the aftershave I was wearing as I walked through the doors of Kaupthing. It was probably because it was one of the first times I had actually worn aftershave. It was my first real job and I was seriously stressed. Although I had specialised in finance during my MBA, I had no practical experience. What I had learned in the United States applied to the biggest financial market in the world. How the tiny Icelandic financial market worked was a mystery to me.

I wasn’t born to be a banker. The neighbourhood I grew up in, Breidholt, was Reykjavik’s equivalent to Brixton in London. The son of two teachers, my ambition from an early age had been to follow in their footsteps. Initially I wanted to teach physical education because I loved sport. But though I could easily swing a racket, throw a handball or kick a football, it quickly became apparent that I hadn’t a clue how to explain these skills to someone else. At the age of 21 I decided that academic subjects would be better, and I began studying history at the University of Iceland, intending to be a history teacher. I did well, although I never felt completely at ease there. I suspect the professors mainly remember me because I finished my studies in two years, while the standard was three years. Some of them didn’t like the fact that I did it so quickly and one of them even admitted he had lowered my grade because of it. Evidently he didn’t believe I showed the subject enough respect by rushing through it.

At the time, if someone had told me that my future career would be in business and finance, I would have laughed in their face.

Ever since I was a child I had been known for either losing or giving away any money that came into my possession. The only business initiative I had shown in my early years was when, at the age of nine, I had set up a cinema in my parents’ garage and shown 8mm films to the neighbourhood kids. When my older brother saw the level of interest, he immediately took over the operation on the basis that he was the family’s first born and could easily beat me up. Considerably more business savvy, he charged admission (which I hadn’t thought of), bought popcorn and liquorice wholesale and sold it with a 100 percent margin to the appreciative and mostly illiterate audience. Under his management the garage cinema became an instant commercial success, not surprising given that he even charged me admission, although most of the films belonged to me.

During my college years I must have seemed like a bit of an introvert. I was shy, not particularly comfortable in my own skin. Most of my time was spent on sports, badminton in particular, which I played at an international level, and through which I met my wife, Thordis Edwald, who was the Icelandic champion. I didn’t socialise much in college. I didn’t drink until the age of 19 and without the confidence boost attached to drinking I wasn’t comfortable going to parties or school dances until my final year. I couldn’t even stand up in front of people without hyperventilating and sweating uncontrollably.

In my early twenties, however, all this rapidly changed. Over the next decade I gradually became the complete opposite of my college self. I socialised more and, boring as it sounds, I started to see myself working in an office. I didn’t really think about what kind of office, or what kind of business I would be doing there. It was just the thought of working in a room full of people that attracted me. I had taken a few classes on economic history, and reading Adam Smith, John Locke, Frederick Hayek and Milton Friedman had fuelled my interest in the economy and business in general. What I didn’t know was how to make the transition from history to business. If I were to commence business studies at the university from scratch, that would take another four years. That seemed a long time. When discussing this dilemma with a friend, he told me about the possibility of taking a Master’s degree in Business Administration (MBA), which would take two years. You couldn’t do that in Iceland at the time, but the degree was offered in various other countries. This was an ideal route for me to switch into business. I also fancied the idea of moving abroad, and quickly set my eyes on the United States of America, the Mecca of the business world. Thordis and I decided on Boston, based on the fact that it was closer to home than California. So in the summer of 1992 we and our newborn son, Bjarki, headed for Boston, where I was enrolled in the MBA programme at Boston University.

In Boston, we quickly felt the effect of being from a small country with a weak currency. My student loans were paid out in Icelandic krona, which meant that our financial status was very different in the first year compared to the second year. In the first year, the krona was very strong, so we were able to afford a good apartment in a nice neighbourhood close to Boston College. In our second year, however, the krona had devalued by more than 20 percent so we needed to move to Jamaica Plain, one of the worst areas of Boston, where we lived in a small bug infested apartment with a wolf parading outside our bedroom window. Despite that, we had fun in Boston. We made many friends, mainly international students and Icelanders studying in the area. A few of them would later join Kaupthing and others became clients when they moved back to Iceland. We had also made friends through playing badminton, which we mainly did to scrape together some money. Thordis did some coaching and we also travelled to tournaments, mainly to win prize money. Although it wasn’t huge amounts of money, it made a considerable difference if we could earn a couple of hundred dollars from a tournament. That also enabled us to travel a bit around the east coast, although most of the sights we saw were the insides of various sports halls.

Living in a foreign city when you are a student is obviously very different from living there when you have an income. When we came back to Boston with some friends a few years later, they were massively unimpressed by our knowledge of the city. We had no idea about where the restaurants, bars and cultural highlights were. The two years we lived there, we had no money so we never ate out, unless it involved waiting in line to order and cleaning up after yourself. With a young child, the few times we went out were really just drinks at a friend’s house. Much to my chagrin, I didn’t even manage to go to see the Boston Celtics or the Red Sox while we lived there.

I enjoyed the MBA hugely. I had decided to specialise in finance even before the programme began. I did that without knowing what finance exactly was. My reasoning was that because my undergraduate studies were in a fluffy subject like history, I needed to specialise in something analytical to be taken seriously when entering the job market. That ruled out marketing and human resources. Accounting sounded boring, so I picked finance. As it turned out, I actually enjoyed finance very much and it became my favourite subject anyway. I found applying the rules of the market to real life problems fascinating. I was also still uncomfortable speaking in front of people so I found some of the management and marketing classes, where participation in discussions was very important, more uncomfortable. Burying my head in a book with only a calculator for company was more up my street at the time. Despite the ‘fluffy’ background I did very well in the programme, graduating somewhere close to the top ten percent of my class. At the end of my studies I briefly considered whether to seek employment in the USA but decided against it in the end. Because I didn’t have any work experience before the MBA, which was unusual, it was difficult for me to find interesting work. Also I wanted to go back to Iceland. I’ve always been very attached to my home country, and at that stage, being abroad for two years felt like a long time.

Back in Iceland though, finding a job in finance, or in anything else for that matter, turned out to be a difficult task. The economy was not in great shape and my academic background wasn’t winning me any favours. Headhunters suggested that I might be more suited to journalism than business, whilst recruiters at Icelandic banks looked at my MBA with a mixture of distrust and suspicion. At 26, I was unemployed, debt-ridden, with a wife, a young son and a baby due.

Luckily, my father had been on the lookout. In November, he had bumped into a cousin in an art gallery and discovered that he was an executive at a small brokerage firm called Kaupthing. The cousin agreed to see me, and asked me to work on a temporary assignment between Christmas and New Year, helping the back office to settle an Initial Public Offering (IPO) for a recently privatised pharmaceutical business. Later, colleagues used to joke that he had forgotten about me, so didn’t ask me to leave until it was too late. But with only 28 employees working in Kaupthing at the time, that wasn’t too likely.

Kaupthing had been founded as an advisory and securities firm in 1982. In Icelandic, the name means an exchange or marketplace. Its eight founders were young, well-educated idealists, interested in developing a financial market in Iceland. At that time, there wasn’t even a stock market. In a tiny country with limited opportunities, survival depended on being a jack of all trades. A newspaper at the time described the operations of the new company as ‘any kind of advisory and research services in the areas of macroeconomics and management, IT consulting and services, sales and marketing consultancy, investment advice, bond and equity brokerage, asset sales, asset management, real estate brokerage, sale of companies, aircraft and ship sales, and any services related to these businesses.’ The business lines appeared to outnumber the staff.

Over the next decade the new company’s focus narrowed and it aborted its consulting practice and real estate agency activities, becoming a more specialised securities house. When a stock market was established in the mid-eighties, Kaupthing quickly became an active participant. Its ownership and management changed a few times over this period. In the early nineties two financial groups jointly owned Kaupthing. One of them was the savings banks group and the other was Bunadarbanki, the agricultural bank of Iceland, owned by the government. At the time there were three major banks in Iceland: two of them were government owned, Landsbanki and Bunadarbanki, while the third Islandsbanki (later Glitnir) was publicly listed. They were all of fairly similar size, although Bunadarbanki was the smallest by most measures. All had purely domestic operations. Landsbanki had the largest equity base, amounting to just over £50 million. To us this was a massive amount, but to anyone outside of Iceland it was tiny. There were only four brokerage houses of any meaningful size, including Kaupthing. At the time, the commercial banks all owned separate brokerage houses. The banks focused on lending, while their brokerage subsidiaries specialised in brokerage, asset management and corporate finance activities. Capital and balance sheets were for the most part safely separated from the brokerage and advisory business. Investment banks were unheard of.

In 1994, then, the company was small by any standards, even Icelandic ones. We didn’t have our own building, and rented one and a half floors, covering approximately 1000 square metres. There were only two divisions: asset management and what was called the securities division. The asset management division both operated mutual funds and managed money for private clients while the securities division did pretty much everything else. I joined the securities division in the beginning. We were involved in the broking and trading of both equities and bonds, but also corporate finance and foreign exchange and derivatives trading.

Chinese walls were as alien to us as, well, a wall from China would be in Iceland. That didn’t mean, however, that ethical standards were low; on the contrary people were well aware that they were often privy to sensitive information and would place big emphasis on confidentiality. Staff’s own trading was frowned upon and trading in unlisted shares was banned internally, although no such ban was forced upon us by the regulators. In a way, light regulation at that time probably made people take more ethical responsibility themselves.

As I walked through the office on my first day, I met the people who were to lead the company’s meteoric rise over the next 13 years. The CEO at the time was Gudmundur Hauksson, but he would shortly leave his post. The other key people who would stay on were mostly fresh out of college and had recently joined. When the generation above us left over the next few years, we were ready to move into management, with big ambitions and unshakeable confidence.

Of all these people, Sigurdur Einarsson would probably do the most to influence the events of the next decade, not only for Kaupthing but for the whole financial market in Iceland. Ten years older than me, his prior experience at Islandsbanki and Danske Bank gave him prestige in the company. His fluent Danish also gave us an advantage later, when we expanded into the Nordic countries. He started as head of the securities division, but less than three years later he would be CEO. Short and stockily built, squint-eyed, with an ever-receding hairline, Sigurdur resembled nothing so much as a young Winston Churchill. He was tough too, but he kept his friends close. As I used to joke, he was like Russian toilet paper, rough on the edges, but definitely better than nothing when you’re in need. Far from being a micro manager, he tended to give the younger people a lot of freedom and responsibility. Known to exaggerate numbers, he once famously answered the question ‘how many people live in Iceland?’ with ‘less than a million’ – the population was slightly more than 250,000 at the time. This bullish hyper-confidence set him apart from the rest of us – in the beginning, he was the only one of us who really did have a boundless imagination about what we could do.

Three other key players, Hreidar Sigurdsson, Magnus Gudmundsson and Ingolfur Helgason had also joined shortly before me. All were business graduates from the University of Iceland around my age, with little experience of the wider world.

Hreidar was an innovative thinker and fantastic dealmaker; he was behind some of the best-known deals we ever did. He was very thin with ears so big that we joked that his head looked like a trophy. As a child, an arrow had been shot into his right eye, partially blinding him and giving him a lazy eye. Every time a deal didn’t go right, he claimed that he’d looked at it with his bad eye. Naturally hyperactive, the invention of the BlackBerry led to him develop the attention span of a squirrel. Yet Hreidar was a top student, and fantastically analytical. He could read through financial reports at the speed of light, quickly spotting the necessary information. His creative mind was naturally entrepreneurial; he thought like many of the big players we met along the way. He started out in asset management, but by 1998 he had become the deputy CEO. Subsequently he became more involved in our corporate finance and proprietary trading activities.

Ingolfur was short with blond hair, though like Sigurdur’s his hair receded as Kaupthing grew. We had played badminton competitively together as children, making him the only one I knew before starting at Kaupthing. He became known as the ‘fashion police’ – he was such a neat dresser we always suspected him of ironing his jeans – he was relentless in advising the rest of us on what was and was not acceptable. But his down-to-earth common sense made him a vital asset with investors, who trusted him implicitly. He was crucial to our early attempts to raise capital in Iceland, for ourselves and our clients. In 2005, he was made CEO for Iceland.

What Ingolfur did for institutional clients, Magnus did for the private client business. Tall and athletic, he stood out in a crowd. He was a shrewd investor, always more at ease with numbers than languages. But he was also a great people person. He was chosen to spearhead our expansion overseas and moved to Luxembourg to set up our offshore banking services in 1998. He performed fantastically and customers loved him. One of his major clients even moved to his neighbourhood in Luxembourg to be near him. For some time, anyone with any money in Iceland banked with us in Luxembourg.

And me? In my first few years at Kaupthing, I moved around a lot, not quite settling in. Still quite shy at this point, I didn’t bond quickly with people. The girls in the back office later told me they thought I was slightly backward because I spoke so rarely. The first time I had to make a small presentation to the management, I only barely avoided fainting and perspired so heavily that I had to go home and change shirts afterwards. Worst of all, only three weeks into the job I managed to make a serious faux pas at the first office party. Nervous, and surrounded by people I didn’t really know, I drank quickly. When someone started to tell jokes late in the evening, I had enough Dutch courage to follow up with my own jokes. The first two went well, so I eagerly followed them up with a third, completely inappropriate one, involving a morgue and dubious sexual activities. Silence descended on the room. I was mortified and, out of the corner of my eye, I could see my cousin, who had recruited me, looking down at the floor in disgust. Permanent employment seemed highly unlikely. In the end, though, what seemed like a disaster turned out to be a blessing. Hreidar told me later that this was the first time he, or most other people, had noticed who I was.

I was involved in research, brokerage, foreign exchange, derivatives, and for a while I was responsible for the funding of the firm. Various activities that required contact with the world outside Iceland often found their way to my desk. The firm was small and it was helpful to be able to multitask. I was equally strong in languages and finance, which was probably the reason for the wide range of activities. As Kaupthing grew and became more specialised I eventually settled down as head of investment banking. That was the division that worked on mergers and acquisitions, arranged and underwrote equity offerings and IPOs. Success was based on building relationships with corporate clients and entrepreneurs, and over time I became quite good at it.

The culture that was formed in the early days was unique. We were young; we wanted to have fun, and that created a ‘work hard, play hard’ atmosphere that became Kaupthing’s trademark. Internal competition was fierce, not only in terms of profitability, but also in terms of what division created the best comedy act at the Christmas party or who organised the most intellectually stimulating morning meeting. We met up for drinks after work, organised karaoke competitions and went camping at the weekends. Hierarchy was almost non-existent and reflected Iceland’s classless society. It was common to see the janitor chatting to the CEO at an office party. Being part of a prominent family created no respect, unless it was accompanied by skill and intelligence. At Kaupthing it wasn’t important who you were, what mattered was what you were capable of. The culture was fairly male dominated, as tends to be the case at brokerage companies and investment banks. The split between men and women was equal in total numbers, but in the front office men outnumbered women greatly, and the opposite was true in the back office. Applications for brokerage jobs was heavily skewed towards men and that was reflected in the recruitment numbers. Of course we still had a good number of women in the front office and I don’t think anyone who worked there would have described the culture as sexist. Yet we still had the reputation for being a boys’ club and there was some truth to that.

Our sense of humour was quite hard-hitting – we loved nothing more than a practical joke. Sometimes it all got a bit out of hand. One member of staff who was celebrating his 30th birthday secretly hired an actor to attend the party and give a speech. The actor pretended to be a client of Kaupthing whose life had been ruined by investment advice given by the birthday boy. He became more and more foul-mouthed and aggressive during the speech until the guests were in a state of complete shock. When a fight erupted between the guest and the host, the ninety year old grandfather of the birthday boy, a former supreme court justice, started to shake uncontrollably and had to be carried away. By the time it was finally revealed that people had been witnessing an act, the atmosphere had been destroyed and the party dissolved.

The newer members of staff bore the brunt more often than not. When the King of Sweden was on a formal visit to Iceland, a broker who had recently joined was told that the King would be visiting the trading floor. A water pipe under the hard wood floor had recently burst, causing the surface of the floor to swell slightly. The broker was told that he would have to stand on top of the bulge so the King wouldn’t notice it. After half an hour later, with no sign of the King, the snickering on the trading floor became loud enough for the red faced broker to realise that he had been had. Unfortunately, the young broker took the ill-fated decision to get back at his tormentor. When an e-mail was sent round to all staff announcing drinks after work, the victim used a colleague’s computer, to reply to all with the sentence: ‘I will be there with a massive hard-on!’ Unluckily for him, this was a violation of both e-mail policy and sexual harassment policy; after only a few weeks at the bank, he found himself out of a job.

Even our more senior people were not spared. Shortly after a new head of legal joined, I placed the first major transaction on his desk. One of the large fishing companies, located in Akureyri in northern Iceland, was considering a major takeover of a company in Denmark and they wanted us to advise on the transaction. The first thing they needed was a letter of intent they wanted to sign with the seller. Our man got cracking and after some dialogue with the CFO of the fishing company, he flew to Akureyri to meet with the company and the Danish lawyer representing the seller on a Friday afternoon. The CFO introduced our lawyer to the Danish lawyer, who turned out to be a beautiful blonde in her thirties, then swiftly left the room. As they started running through the letter of intent, our man started to notice some peculiarities in the young lawyer. For one her Danish accent sounded awfully Swedish. Also, although the girl was wearing a typical business suit, he had never seen anyone in business wearing open high heel sandals with carefully varnished toe nails. When she began to complain about the high temperature and unbutton her shirt, his suspicion grew. His suspicions were confirmed when a group of his closest friends and colleagues jumped into the room at the same time as the ‘lawyer’ (who turned out to be a Swedish exotic dancer) ripped off her shirt. Our new employee was getting married a couple of weeks later and we had done all this to trick him into a stag do in Akureyri.

Clients came to love the corporate culture at Kaupthing. In the early days, client entertainment was heavily scrutinised and done quietly, on a small scale, so it wasn’t perceived as a sign of excess. It became clear though, that nothing was better for building up trust and relationships. We organised salmon fishing trips, invited clients on trips abroad to meet financial institutions, and set up seminars in Iceland. It wasn’t so much the nature of the events that made us successful, but rather the atmosphere we created. We didn’t spare them the wicked humour and the teasing that was a big part of the culture – and most took it in their stride. Of course, we sometimes overstepped the mark. On one fishing trip at a salmon river in Western Iceland, I noticed that one, very overweight, prospective client was sharing a tiny room with Sigurdur Einarsson, himself not a thin man. Looking at them and their bags, I innocently asked ‘where are you two going to keep the luggage?’ Not surprisingly, we didn’t get much business from the client after that.

But we matched all this with a work ethic more akin to that of an American investment bank than anything that had come before in Iceland. We worked evenings and most weekends. If we were competing we never gave up. Once, one of the pension funds in Iceland was selecting an asset manager to run their portfolio of assets and decided on another firm without considering us. When we learnt of this, we harassed all their board members until they agreed to allow us to submit a proposal. Unfortunately the board meeting was the following day and we had no presentation or proposal ready. We worked through the night and until midday the following day to finish the presentation. Even though the board had already made up their mind and was really only humouring us by allowing our presentation, they were hugely impressed with our proposal. So they decided to split the portfolio in two and gave half of it to us to manage. I left the office at lunchtime the second day, after working 30 hours without stopping, only to find that our HR manager took off a half day’s salary. She correctly pointed out that according to my agreement I didn’t get paid overtime, and if I left early a deduction would be made from my salary!

Looking back, the numbers and amounts we were dealing with at the time sound very modest. The biggest asset management clients had the equivalent of £2-300,000 under management. To us this was a huge amount of money; one could only dream of ever building up that kind of wealth. The amounts involved in securities trading were in proportion to this. In my first year we frequently had days in the stock market where no shares changed hands. The profits were modest too. In 1994 profits were around £200,000 and in 1995 profits actually declined to £175,000. Still, these were considered fairly decent in Iceland at the time.

Salaries and remuneration were in line with the size of the company, but also the prevailing views on income distribution. The CEOs of the biggest companies in the country received around £100,000 annual compensation, but unlike in the US and the UK, by that time, it was unheard or for bankers or brokers of any kind to receive anything close to that amount. When I started out my basic salary was £15,000 and I couldn’t believe how well I was getting paid. Two years after I started, Sigurdar put in place a long-term incentive plan. Previous attempts to allow employees to buy shares in the firm, or issue shares options to them, had come to nothing, blocked by the board. Increasingly, this was a problem, as Kaupthing grew and the staff became more and more sought after in the marketplace. Everyone liked working there so much that we practically never lost key personnel, but as increasing amounts were offered, the pressure mounted. Finally, Sigurdur came up with a long-term incentive plan. It was simple. Around ten of the key people in the business were promised a lump sum payment in three years, if they hadn’t left by then. The amount we were promised was to me an amazing amount of money, as much as one million dollars would have sounded to an American investment banker. It was one million kronur, the equivalent of £8,500. One of my colleagues declined to be part of the plan, as he didn’t want to be tied down for such a long time. When pointed out to him that of course he could leave at any time, even if he was part of the plan, it still didn’t change his mind. Being a bit of a bohemian, he didn’t want the prospect of such a huge amount of money clouding his mind. He ended up working for Kaupthing for another six years. Three years later, though, the amount looked puny, considering that in the intervening years, we had grown the value of the firm by approximately £50 million.

Beyond the numbers, Kaupthing was a small company. Shortly after I joined there was an uprising in the back office, due to what became known as the ‘Big Switchboard Scandal’. The switchboard was managed by one person only and she was obviously entitled to her lunch and coffee breaks. We had a system of replacement, where the girls in the back office were asked to take turns in managing the switchboard during coffee breaks and lunches. This wasn’t a popular task and one day the dissatisfaction erupted. The view of the back office workers’ ‘union’ was that answering the telephone wasn’t their job any more than it was the job of the brokers and traders. With the wisdom of Solomon, Gudmundur the CEO decided that all staff members, excluding himself, would now fill in on the switchboard.

Star traders sat sour-faced in reception with the headphones on while sniggering colleagues walked by. Naturally, the incoming calls were sometimes for the selfsame person who was on the switchboard at that time. More often than not that person would pretend to be someone else, calmly replying ‘I will see if he is in’, pressing mute and then unmute before answering as himself. A few weeks in, I became a victim. At my brother-in-law’s birthday party I had met our CEO’s lawyer. We had spoken quite a bit at the party and discussed my job at Kaupthing. With each drink, the importance of my role at Kaupthing grew. Only a few days later the lawyer came to the office to see the CEO. As luck would have it I was wearing the headphones in reception. In my head, I quickly calibrated the options of trying to explain the switch board system or pretend I had never seen him before. I opted for the second choice and sent him through to our CEO without flinching. After a few weeks and a number of similar incidents, the system was abandoned and a second receptionist was hired for the switchboard.

Around Christmas time each year, Icelanders flocked to buy shares before year end. Tax incentives at the time allowed people to deduct a proportion of the shares they had bought from income tax. Of course, people could buy shares anytime during the year, but in typical Icelandic fashion they tended not to do anything until the last minute. This meant that in the week between Christmas and New Year, the volume of share buying was several times the amount traded in a normal week. There was no way the brokers and asset management staff could handle the volumes. People were queuing up outside our office and everyone, no matter what their job description was, would be given a desk to sell shares. This was done either over the phone or in person. Even the CEO would turn into a broker. Some of the elderly clients, coming to buy £1000 worth in Kaupthing’s equity fund, almost had a heart attack when they were shown into the CEO’s office to close the transaction.

The markets weren’t that impressed by the changes at Kaupthing in 1994 and 1995. More experienced staff were leaving, and rumour had it that Kaupthing was in trouble. For a while, we did struggle a bit, but we soon learned the ropes. Although there was a mix of people, the culture that emerged reflected the things we all had in common.

Crucially, we were all outsiders in Icelandic business. None of us had any connections to the business establishment or political powers at the time. The sons of teachers, sailors and electricians, we had little regard for the establishment. It wasn’t that we were out to shake the balance of power, it’s simply that we didn’t care whether we did or not. We were fiercely ambitious, and that ambition was focused purely on building the business and making profits. Whether we ruffled some feathers along the way was of no consequence to us. We were so small in the beginning that no one particularly noticed what was brewing within the walls of Kaupthing. Important changes that were taking place in Iceland would, however, create a very exciting platform for us to grow from. We were about to take full advantage of that opportunity.

Chapter Two

The Financial Caterpillar

In the mid-nineties Iceland was hardly buzzing. It was probably the last place on earth you would expect an exciting business environment to brew. The country was at the tail end of a six-year economic downturn. A 20 percent reduction in purchasing power had left many in a tight spot. The economy was a one trick pony at the time, far too dependent on fishing, which accounted for close to 70 percent of exports. A collapse in the cod stock in the eighties, followed by a sharp reduction in fish prices in the nineties, had hit the economy hard.

Still, the country had come a long way. Sitting isolated in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, Iceland is barely habitable due to the rough terrain and unforgiving weather. It was settled mainly by Norwegians in the ninth and tenth centuries who fled their native land to escape heavy taxes, and regain autonomy from the Norwegian King, Harald Fairhair. Wind, rain and snowstorms were obviously preferable to the heavy duties that these tax-avoiding, freedom-seeking settlers were fleeing from. But over the course of a thousand years, the weather and volcanic activity regularly did their best to eliminate the population, and came close a few times. At the end of the eighteenth century the population was down to almost 30,000 people. Icelanders were nearly extinct.

In the early twentieth century the majority of the population still lived in mud huts. As late as at the beginning of World War II, Iceland was among the poorest nations in Europe. The country benefited financially from the war, however, and received Marshall Aid in the aftermath. In the second part of the twentieth century the position turned upside down. When I started working at Kaupthing, Iceland was already one of the richest nations in Europe by any measure.

How had this happened? Ironically, the wealth was created by leverage. Not by financial leverage – that would come later – but rather the leverage of vast natural resources compared to the size of the population. About one-and-a-half times the size of Ireland, Iceland has two important natural resources: generous fishing stocks and enormous energy, both geothermal and hydroelectric. Tourists also flock to see the spectacular volcanic landscape. Measured on a per capita basis, Iceland attracts more tourists than France. Like a Middle Eastern oil state, Iceland had a lot of resources for a small population, and started to use them efficiently.

Natural resources aside, Icelanders also like to work. Historically, unemployment has been almost non-existent. Over the last 30 years unemployment has typically ranged between 1 and 2 percent and the very highest rate was 5 percent – close to what many economists deem to be ‘natural unemployment’. Working the system was almost unheard of. In many cases, even when people are unemployed, benefits are so frowned on that they remain uncollected – they are only ever a very last resort. But benefits are also relatively low, in stark contrast to the social democratic paradise offered by other Nordic countries.

Despite increased prosperity, Iceland was not a very liberal society when I was growing up. It was a bit backwards in many respects and its peculiarities caused raised eyebrows amongst foreign visitors. Private ownership of radio and television was banned until the mid-eighties. Instead, there was one state-owned TV station, and one state-owned radio station. The radio spent only two hours a week on two shows that played pop music. One was called ‘Tunes for the teens’ and the other was, extraordinarily, called ‘Songs for the sick’, in which people in hospital sent in to request particular songs. Not surprisingly, these tended towards the sentimental, filling the airwaves with ‘I can’t smile without you’, ‘Yesterday’, and ‘Stand by your man’ The television was similarly conservative. To add insult to injury, the station did not broadcast on Thursdays or at all during July. Members of parliament even debated the need to broadcast television in colour.

Attitudes towards alcohol were also restrictive. For a long time people were not allowed to buy alcohol in restaurants and bars on Wednesdays, and beer wasn’t allowed at all. As a replacement, people would drink what was called ‘ersatz beer’, a horrific blend of low alcoholic pilsner and vodka. All alcohol beverages were only sold in special purpose wine stores, owned and run by the government.

In the late eighties, however, a wave of liberalism washed over the island. Both privately owned radio and television stations were allowed and beer was made freely available in March 1989. The government television station even went with the flow and started to broadcast on Thursdays and in July. On the back of this wave a man who would change the landscape of Icelandic politics, re-energise the economy and give freedom to the capital markets was climbing to power. His name was David Oddsson.

Oddsson was a member of the Icelandic Independence Party, the biggest and most powerful in the country. Unlike other Nordic countries, where social democrats tended to be in power, in Iceland the leading party for the majority of the last century was centre-right, somewhat similar to the British Conservative Party. After being one of the most popular mayors Reykjavik ever had, Oddsson launched what you might call a hostile takeover bid to become the leader of the Independence Party. In 1991 he formed a government with the Social Democrats and became the Prime Minister of Iceland at the age of 43. He would hold the position for a record 13 consecutive years.

A relatively short, chubby man, Oddsson wouldn’t catch your eye if it weren’t for his unusual Afro-like hair. But, behind the modest exterior there was a brilliant and very determined mind. He became a superman in Icelandic politics and, at his peak, he was undoubtedly one of the most powerful men the country had ever known. The source of his power was not just his position, but his intelligence, wit and ruthlessness. He was a phenomenal orator – whether in parliamentary debate or in private arguments, he could be pretty sure of winning. Yet he was also a fiercely aggressive man, and so intensely well-connected that he knew everything about everyone. People desperately tried to avoid making him an enemy.

It was under Oddsson’s leadership that Iceland went through such a massive change in the nineties and early 2000s. In 1994, Iceland joined the European Economic Area, resulting in the free flow of capital, goods, services and labour to and from the country. As international opportunities opened up, the younger generation began looking overseas with great excitement.

At the same time Iceland went from being probably the least marketoriented of the Nordic countries, to the most. Taxes were lowered to a level not seen in any other Western European country apart from Ireland. Government influence was diminished and, in a Thatcherite privatisation effort, state-owned companies were placed in the hand of private individuals. The disposal of the government-owned banks fuelled the rapid growth of the financial system. In less than a decade, Iceland became a capitalist heaven. The flipside of this coin, though, was that the power and influence of politicians over the economy declined. Those that took the most advantage of the liberalisation were not the established businesses, but rather the younger generation. Ironically, as that happened, the man responsible for the development didn’t like it at all.

The business environment was changing, and so were things at Kaupthing. The small business volumes in Iceland at the time meant that we would get involved in almost anything we could think of that generated revenues. This spurred innovative thinking and resourcefulness, which would become the hallmark of the firm. Indeed, many of the things we did genuinely broke new ground.

We created products that hadn’t existed before. People were encouraged to be innovative and they were given freedom and responsibility to develop new opportunities, in large part as a result of Sigurdur’s management style. I developed the first foreign exchange options on the Icelandic currency, the krona, in 1996. The options gave companies the opportunity to buy or sell krona at a fixed exchange in the future, making it possible for them to hedge against adverse currency movements. Sigurdur had been instrumental, while at Islandsbanki and before joining us, in making the first forward agreements on the krona, making a lot of money for Islandsbanki in the process. In early 1996 he mentioned to me that he thought there would be great demand for options on the krona if we could develop them. I had taken derivative classes during my MBA so I told him that I thought I could do it, much to his delight. When I started looking into it, I quickly found out that properly hedging any options would be a problem. We could partially hedge our exposures by trading in and out of the underlying currencies, but the only way to hedge against changes in volatility was to buy options and they didn’t exist. We were still so keen to be able to offer the product that we concluded that we should accept a greater risk by charging for it through higher pricing. Fortunately, the options had limited commercial success, due to the high premiums we had to charge to compensate for liquidity and volatility risk. I was quite relieved – not a natural risk junkie, I didn’t really fancy running a big option book that couldn’t be hedged properly.

The swap products we developed on the krona were much more successful. These enabled investors to receive high interest rates in krona while paying lower rates in foreign currencies, a transaction often referred to as ‘carry trades.’ The idea for the instruments came during my trip with Hreidar to New York in 1996 where we had been pitching to investors to buy Icelandic Treasury Notes. Interest rates in Iceland were considerably higher than in most other countries and American investors could pick up a yield difference of six percent between the krona and US dollar. An investor needed to accept the foreign exchange risk, as any devaluation of the krona would cause him losses. Investors found the market small and illiquid. Flying back we discussed whether we couldn’t somehow generate the yield difference between the krona and other currencies for Icelandic clients, who were willing to take the foreign exchange risk, and the idea for the krona currency swaps was born. What we intended to offer was a swap where they received high interest in krona and paid us in turn much lower interest rates in foreign currency. We wanted to offer a three-year trade with the sale pitch that if the exchange rate was at the same level at the end of the three years, the profits would be 20 percent of the nominal amount of the swap. The krona had been stable for a long period of time so we were pretty certain that there was investor appetite for the product. The problem we had was that there was no derivatives market available to hedge our exposure, which was the opposite of our investors.

What we did was to buy the underlying Treasury Notes, which paid the krona rate. We then borrowed the equivalent amount in a basket of currencies resembling the krona trade-weighted index from a German Landesbank by pledging the Treasury Notes to them. As we predicted, there was a big appetite among investors and we quickly sold swaps for £10 million, which was a very large amount at the time. The profit to us over the period of the swap was close to half a million pounds, a massive amount at the time. The trade was successful and at the end of the three-year period, investors reaped impressive profits. We felt like geniuses!

Innovation started to flow at Kaupthing. We were the first financial institution in Iceland to offer guaranteed products, securities that guarantee the investor repayment of the nominal amount they invested and additionally a percentage of the increase of, for instance, a stock exchange index. Early on we approached some of the foreign companies that had subsidiaries in Iceland and issued debt for them in Icelandic kronur to reduce their exposure to the krona.