Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jentas Ehf

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

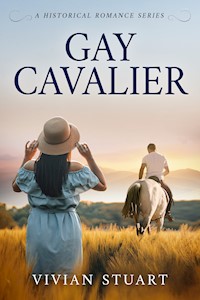

- Serie: Historical Romance

- Sprache: Englisch

INTRIGUE. TENSION. LOVE AFFAIRS: In The Historical Romance series, a set of stand-alone novels, Vivian Stuart builds her compelling narratives around the dramatic lives of sea captains, nurses, surgeons, and members of the aristocracy. Stuart takes us back to the societies of the 20th century, drawing on her own experience of places across Australia, India, East Asia, and the Middle East. It was hard on Deirdre that she should come to care for a man whom her dearly loved artist brother, Sean, hated so deeply and, as he believed, with such good cause. And Sean, too, had his troubles, loving a girl whose father disapproved of him. Their romances are linked with the fortunes of the Sheridan Stud in Berkshire, where hunter and steeplechasers are bred and schooled, and the book is full of the charm of fresh country air and springy turf.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 311

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Gay Cavalier

Gay Cavalier

© Vivian Stuart, 1955

© eBook in English: Jentas ehf. 2022

ISBN: 978-9979-64-470-5

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchase.

All contracts and agreements regarding the work, editing, and layout are owned by Jentas ehf.

CHAPTER ONE

DEIRDRE SHERIDAN saw her father’s horsebox turn into the yard and tore herself away from the excited little crowd of children on ponies which surrounded her, with a quick:

“Look, I simply must go — our horses are here.”

The children let her go reluctantly. As one of the instructors at their weekend Pony Club Camp, Deirdre was a figure of some importance — as “Hare” in the paperchase which was to highlight the end of the camp, she was vested, in their eyes, with the trappings of heroism. Besides, she was nineteen and therefore grown up.

But she made her escape at last and hurried into the yard. The horsebox was unmistakable, for it was new and very resplendently painted in maroon and grey — her father’s racing colours — with his name boldly emblazon cd in letters of gold across the board in front:

Captain Dennis Sheridan, The Sheridan Stud, Kings Martin, Berks,

Beneath it was the head of Merry Marcus, which Sean had designed as a sort of trademark, an exaggerated portrait, done in oils, which showed the old horse with nostrils distended and ears laid back, as if his invisible body were arched up beneath him in a frantic effort to thrust him past the post a neck ahead of his equally invisible rivals.

It was extremely effective, but, in fact, Sean had painted it from his imagination, with old Marcus eyeing him benevolently over the door of his loosebox. It was four yean since either of them had raced, six since Marcus’s totally unexpected triumph in the Grand National had made his name, for a brief space, one to conjure with.

Deirdre stood looking up at the board, a frown drawing her fine, dark brows together in a worried pucker. Her father, catching sight of her, called out with eager pride:

“It looks very grand, does it not?”

His strong brown hand caressed the gleaming paintwork of the horsebox, and Deirdre’s frown dissolved into the ghost of a smile. He was like a little boy with a new plaything, she thought affectionately, and hadn’t the heart to disillusion him. Although her interview with the Bank Manager yesterday, when she had gone to draw the wages cheque, had not been particularly reassuring.

“Miss Sheridan,” he had warned her, in his prim, flat voice, “if you have any influence with your father, try to make him see that matters cannot go on as they are. The Bank has been lenient with him, extremely lenient But his overdraft is now a long way above the agreed maximum . and he’s made no attempt to reduce it He’s spending money like water! That new horsebox, now — surely it wasn’t necessary?”

It depended, of course, on what you meant by necessary, Deirdre reflected wryly. Her father believed it was and, when she had tried to tackle him on the subject and on that of his overdraft he had flashed her his charming, boyish smile and used her arguments and the Bank Manager’s to reinforce his own.

“Sure now, if we can sell Moonbeam to this Carmichael fellow, Deirdre, for anything near what he’s worth—well, that would take care of the overdraft, wouldn’t it? And you can’t be asking top prices for your horses if you’re after carting them about in some broken-down old cattle truck, can you now? Be reasonable! Money breeds money—this horsebox is the finest advertisement I’ve ever had and, as such, it’s an investment It will pay for itself in no time at all, so it will. And if you’re really worrying about the overdraft—ach, sure, ’tis the simplest thing in the world to be ‘rid of it! Just ride Moonbeam in the paperchase tomorrow and sell him to Alan Carmichael—’tis all you have to do. He’s only to see the horse’s performance to want him, And he’s rich and can afford to pay a decent price. They say he’s Wanting to race and he can’t do that without good horses, can he? Tis fortunate that I’ve the animals to sell him, for his own sake. Isn’t it then?”

Put like that, it all sounded perfectly feasible and absurdly easy. Dennis Sheridan never recognized the faintest possibility of his plans going awry: it seldom occurred to him that they might.

But, Deirdre reminded herself uneasily, as her father led Moonbeam out of the box, Colonel Alan Carmichael was a newcomer to the district, a complete stranger to her, whom she had seen only once—a tall, fair-hawed man with a strangely forbidding expression—hurtling past her at the wheel of a powerful sports car.

Rumour, whilst crediting him with considerable wealth and a fine military record, also had it that he was unapproachable. People who had called on him at Manor Farm, which he had recently purchased, had met with a brusque welcome. He had stopped short of open incivility but he had not encouraged any friendly advances, nor offered more than the minimum hospitality which convention demanded.

It was said that he had only lately retired from the Army, having served in Korea where, like his brother Sean, he had been a prisoner in Chinese hands. The charitable excused his brusqueness on this account: the others were less tolerant.

Today, at Sir Henry Hollis’s invitation, he had come to judge the Pony Club’s Stable Management, but Deirdre, busy with her own classes, hadn’t seen him. Her father was taking a good deal for granted, she thought—his judging over, Colonel Carmichael might quite easily go home, instead of waiting to watch the paperchase and Moonbeam’s performance. And, in any case, whatever her father might say, Moonbeam wasn’t everybody’s horse.

Deirdre sighed as she watched Paddy, the Stud groom, tightening the horse’s girths. Moonbeam was a handsome,’ grey, beautifully bred and up to any amount of weight: a fine, bold jumper with a great heart But he was young and he needed riding: he was by no means the ideal horse for an amateur who just wanted to ride in a few point-to-point races. It would have been better to have offered him Snow-goose or even Rudolph, although, of course, neither could command Moonbeam’s price. And there was that wretched overdraft . . .

She would have to do her best to sell Moonbeam to Colonel Carmichael, but it wasn’t going to be easy, even supposing he stayed on for the paperchase. Deirdre knew that she need expect no introduction from any of the Hollises, whose guest he was today. The Hollises were snobs and disapproved of her only a little less than they disapproved of her father, because he bred horses for a living and wasn’t “county.” But Penelope Hollis at any rate could be relied on to point her out to the newcomer, if only in order to express her disapproval. Once identified as Dennis Sheridan’s daughter, all she would have to do would be to keep Moonbeam prominently in Colonel Carmichael’s sight and, if current gossip were correct and the colonel on the lookout for one or two horses, it was possible that he would approach her.

If he didn’t, of course, then she would have to make the first move herself—a prospect she did not view with any great relish, after the stories she had heard. But— her father would expect it of her. And Dennis Sheridan, for all his more Obvious faults, was the best and most indulgent of parents. Deirdre would have gone through fire and water for him, if at any time he had expected this of her. She adored her father. And selling his horses was her job.

“Well, child?” Dennis had come up behind her and she turned to smile at him, thinking, as she did so, what an attractive man he was, with his tanned skin and his gay blue eyes, his crisp fair hair and his slim, lithe body. He was in his middle forties but he didn’t look it, for he had an ageless charm and the light-hearted exuberance of a schoolboy.

Today, in his well-cut jodhpurs and yellow waistcoat, he looked both competent and elegant, and Deirdre regarded him proudly. “Well, Daddy?”

Her father returned her gaze with equal pride and an odd fleeting sadness. When he looked at her like that, Deirdre knew that it was because she reminded him of her mother, and her heart contracted. Not that she remembered her mother at all dearly: it had been twelve years Since she had left them and Only Domis still felt her loss. But for his sake Deirdre was sorry and, impulsively, she went to him and linked her arm in his.

He said gruffly: “Time to get up, child. Come on.”

He led her over to Moonbeam, his head on one side and his eyes narrowed as he studied fee grey. “He’s looking his best, is he not, Paddy?” he appealed to the old groom.

Paddy’s lined, nut-cracker face split into a grin. “Ach, sure, Captain sorr, there’s not a horse to touch him in the county, so there’s not!” The grin included Deirdre. “Nor a lady to ride the equal of Miss Deirdre, I’d stake me life on ut” He bent, a gnarled old hand extended, to give Deirdre a leg up. “Will I be getting Marigold out now, sorr?”

Dennis nodded absently and, as the old groom vanished into the horsebox, he continued to regard Moonbeam with a speculative but approving eye. He was so far away and so lost in his own thoughts that Deirdre said sharply: “Marigold, Daddy? I thought you were riding Rudolph?”

Dennis turned his gaze on her then. His blue eyes were innocent. “Oh,” he said, “so I was, child, so I was. But I changed me mind, for Rudolph was just the least bit feely on his off fore. ’Twill do Marigold no harm to have a little canter behind the children and maybe pop a fence ‘ or two, when Sir Henry has his back turned.”

“Yes, but——” Deirdre stared back at him suspiciously. “Daddy, what is this, what have you been up to? You promised you’d be Hare with me and Rudolph was perfectly all right yesterday. I don’t see——”

“Do you not then? Ach now, Deirdre!” Her father closed one eye in an elaborate wink. “I’ve unfortunately had to break me promise. But I’ve arranged for a substitute to take meplace.”

“Who?” Deirdre wanted to know and her heart sank as Demis answered: “Who but Colonel Carmichael then? Sir Henry’s lending him a horse. Twill give you the chance you need to sell him Moonbeam, will it not?”

“Well, yes, I suppose so. But——” This was worse than she had expected, much worse. It smacked of sharp practice, to use the Pony Club paperchase in order to thrust Moonbeam under the notice of a prospective purchaser, and Deirdre shrank from taking any part in it But her father added, his tone unusually grave:

“We must sell the horse, you know.”

“Yes, I know. Only——” it was so unlike Dennis Sheridan to display anxiety about anything that Deirdre asked, half teasing, half-serious: “Does the overdraft matter to you after all then?”

At that he laughed. “Ach, divil a bit! I’ve the assets to cover it twenty times over.” He patted Moonbeam’s impatiently arched neck. “This lad’s on his toes. I’d walk him round a little—you’re not due to start for half an hour or so, are you?”

Deirdre looked at her watch. “No. But I’d better collect the bags for the trail. Colonel Carmichael won’t know where they are.”

Her father nodded. “Sean has them in his car—he’s about somewhere. In the park, I think. Go down past the terrace and let Sir Henry see all he wants of the horse while you’re about it”

Deirdre concealed a smile. “All right, Daddy.” Her father was annoyed with Sir Henry because, less than a week ago, the Pony Club’s President had made what he considered an insulting offer for Moonbeam and this still rankled with Moonbeam’s breeder. “I’ll take him into the park.”

“Do that, then.” Dennis hesitated. “You know what Colonel Carmichael looks like?”

“Yes, I saw him the other day, in the village. He’s tall and fair. And awfully young to be a colonel—but rather fierce-looking, so I suppose he must have been one. I’m sure I’d know him again.”

“Indeed you should, from that description. But sure it fits him well enough.” Her. father chuckled but his eyes were still serious. “I’ve no doubt you’ll find Penelope Hollis in his pocket—her mother’s gone to enough trouble to get him here, and it wouldn’t be for anyone else’s benefit, of that you may be sure! Well, off you go—and the best of luck to you. I’ll be giving Marigold a little quiet schooling, where she’s out of the way of the children, for she’s only a baby herself and her manners aren’t as good as they might be in a crowd. But if you need me, you’ve only to send Paddy to fetch me along.” He sketched her a salute. “Ach, but you’re a sight to gladden any man’s heart, on that horse! Don’t forget to let Sir Henry feast his eyes on the two of you.”

“I won’t,” Deirdre promised. She wasn’t at all happy at the thought of what lay before her but there wasn’t really anything she could say. And, when all was said and done, her job was selling horses, not just enjoying herself at a Pony Club camp. She made her way slowly out of the yard to the front of Sir Henry Hollis’s imposing residence.

King’s Martin Manor was Georgian, a graceful terraced mansion, looking out over rolling parkland, where now the Pony Club’s variegated tents were pitched at a little distance from the house.

The Hollises were well off by present-day standards, for Sir Henry had made a very successful career in the City until his retirement two years ago, and he was a very generous patron of all local affairs, including the Pony Club. But even he was feeling the pinch now: the gardens were no longer kept up as they had been, the deer had vanished from the park, farms had been sold off, one by one, from the estate and the indoor staff reduced to a handful.

Nevertheless, on this occasion, hospitality was being dispensed in the traditional grand manner. A buffet had been set out on the terrace in front of the open french windows, and the pale golden sunlight was reflected in silver entrée dishes and great, shining tea urns, in preparation for the expected influx of parents and friends who would arrive during the afternoon. A few had already arrived and were being given hot soup and sandwiches by the butler and his underlings, but the children had had their meal, picnic-fashion, outside their tents and were now busy saddling their ponies for the paperchase.

As Deirdre rounded a comer of the drive, she saw that Sir Henry, very bluff and red of face, was standing on the terrace steps, talking to some of his guests, a cup of soup in his hand and a smile curving his full, cherubic lips. The smile faded as he recognized Deirdre. He bowed to her distantly and his small, shrewd dark eyes flickered over her, from boots to peaked velvet cap, before going to Moonbeam’s handsome head. Then, with visible reluctance, he dragged his gaze back to his companions, only to find that they, too, were looking at Moonbeam admiringly.

Deirdre rode on down to the end of the drive, keeping Moonbeam bunched up under her. The horse, as her father had said, was on his toes, treading delicately over the gravel and snorting as he caught sight of the tethered ponies. He attracted many interested glances before she turned him into the park.

Here she found Sean, beside his parked car at the rear of the stable tent, with—of all people—Penelope Hollis, not yet mounted, who was talking to him earnestly.

Sean’s blue eyes were as innocent as his father’s had been a few minutes ago, but he gave her an impish grin. Penelope flushed and turned away as Deirdre came up to them, murmuring an excuse about secretarial duties awaiting her in the Staff Tent

Her expression, Deirdre saw, was a curious mixture of guilt and defiance. She was a slim, dark-haired girl, whose natural good looks were off-set by a certain primness and whose mouth, in repose, took on a downward curve which was at once petulant and vaguely unhappy. A few years older than Deirdre herself, Pendope was not popular with the other girls in her set But—the only daughter of a rich and influential father—she held an unassailable social position, and on this account she was invited everywhere by everyone, her outspoken intolerance and her conceit excused and explained, or forgiven.

Sean, who was nearer her age had always professed his dislike of her and of all she stood for. He was casually liberal in his ideas, resenting few things save intolerance but that very bitterly, and Deirdre said, surprised: “I didn’t know that you and Peadope were on speaking terms, Sean! What’s come over you?”

Her brother shrugged: “Well, as you’ve seen, we are. The girl has unexpected depths—she’s interested in art. She ‘ came to the Exhibition and expressed approval of some of my pictures. When I’d recovered from my astonishment, we started talking. She bought a picture and I took her out to lunch, so”—he laughed, and put out a thin, long-fingered hand to pat Moonbeam, who was nuzzling him gently— “we’ve been exchanging the time of day quite pleasantly. And discreetly, until you butted in! I must say, Moonbeam does you credit—he’s a good looker. Move over a bit, Deirdre—I’ll include you in my sketch.”

Deirdre backed away and Sean reached into the car for his sketch book. “Over to the left a bit,” he suggested, pointing, “and don’t flap—you’ve plenty of time, none of foe small fry are even up yet . . . yes, that’s fine. Hold it like that, I’ll not be a minute.”

“I’m supposed to be looking for the other Hare,” Deirdre objected, but she held the pose, “and collecting foe bean sacks from you. You have got them, haven’t you?”

Sean grunted abstractedly and jerked his head in the ‘ direction of the Staff Tent “I gave ’em to Penelope. Stop agitating, I tell you, I’ll not be long.”

He worked busily with a pencil, leaning against foe side of his car for support Deirdre watched him, conscious— as she had been ever since his return—of a strange mixture of pity and pride and affection for this unpredictable brother of hers.

Sean had once been Ireland’s leading amateur steeple. chase rider, but a serious wound obtained in Korea—where he had done his National Service—had left him with a limp and a spinal injury which made it impossible for him to sit a horse. It had put an abrupt end to his promising career. He insisted that he did not regret this and, refusing his father’s offer to take him into partnership or set him up as a trainer on his own account, he was now building up a new career for himself as an equine artist, with varying success but every appearance of enjoyment

Deirdre, who had visited him several times in the cramped London studio he shared with two friends of his, knew that he was having a hard struggle. She was glad when he made one of his periodic visits to King’s Martin, for only at home, she felt sure, did he get enough to eat The car, with its specially adjusted controls, was provided by the Ministry of Pensions and was his one luxury. For toe rest he lived frugally, dressed shabbily and worked with concentration and at a speed and pressure which, whilst securing him recognition, seemed to her to be undermining his health.

Studying his absorbed face now, she thought, with a pang, how much he had changed and how thin and pale he looked. Sean had never been particularly robust but he had never looked ill until this last visit

He was a small man, only a few inches taller than herself, fine-boned and slim, with a puckish, unlined face and the bluest eyes Deirdre ever remembered seeing in her life. She wondered, looking down at him, if—in spite of his protests—returning here to this atmosphere of horses and racing hurt him more, perhaps, than either she or her father had imagined. They had moved to King’s Martin after the war but Sean had worked in Ireland. He had never gone back, even for a visit after his return from Korea, nor had he made any attempt to renew his friendships amongst toe Irish breeders and trainers with whom he had been so popular. And . . .

“Well”—Sean glanced up with disconcerting suddenness and met her gaze—“that’s it. Should make a very fetching design for a Christmas card. In fact, I’ve several for next Christmas. Would you like to be on a Christmas card, Deirdre?

“Sean!” Deirdre stared at him. “You’re not designing Christmas cards, are you? I thought——”

Sean gave her his engagingly mischievous smile. He said, curling his tongue round the brogue he sometimes affected: “I am, then. And calendars tool Sure, there’s a grand profit in it Would you be having me turn up me nose at commercial art?”

“Of course not. But——” She could not have explained her uneasiness. Sean had spoken of commissions for serious work but surely . . .

“Forget it,” her brother bade ter. He thrust the sketch book into one of the capacious pockets of his worn tweed jacket and limped over to ter. A hand on Moonbeam’s plaited mane, he said: “I thought himself was to be the other Hare? Why look for him? He’ll know you’re here.”

Deirdre made a little grimace. “He cried off at the last moment You see, he wants to sell Moonbeam and he’s got a prospective buyer fined up. So he’s arranged that the prospective buyer is to be toe other Hare. I don’t lite it much.”

Sean grinned. “Ach, you should know himself by this time! Tis just one of his brighter notions—he means no harm, he’s only trying to pave your way for you. And who is the prospective buyer? Anyone I know?”

Deidre shook her head. “I don’t think you know him—he hasn’t been here long. His name’s Carmichael, Colonel Carmichael, and he’s just bought Manor Farm.”

“Oh? What’s he like?” Sean’s tone was unexpectedly brusque.

“I don’t know, I’ve never met him either, only seen him al a distance.” Deirdre sighed. “They say he’s not awfully friendly and he certainly doesn’t look it But——” She hesitated. Sean never talked of his experiences in Korea and, as a rule, mention of toe word was enough to cause him to relapse into moody silence.

“Well,” Sean prompted, “and how does the colonel excuse his unfriendliness?”

“He was a prisoner in Korea.”

“Was he now?” Sean’s lips compressed. “Carmichael, you say? Do you know his regiment?”

“No. His Christian name’s Alan, I believe, if that’s any help. Did you ever meet him out there?”

From the Staff Tent, a bell sounded a lusty summons, and Moonbeam, startled, tossed his head, spinning this way and that in a restless, excited war dance. Deirdre had her hands too full for a moment to hear Sean’s reply to her question. She said breathlessly: “Goodness, that’s for me—I’d better go.”

“Perhaps you had, Deirdre,” Sean said. His voice was low and shaken and he was looking, Deirdre saw, at a tall, fair-haired man in jodhpurs and hacking jacket who, mounted on one of Sir Henry Hollis’s horses, was coming towards them. She noticed to her astonishment that her brother’s eyes were bright with an emotion she could not analyse. It could have been dismay or even anger but it was almost certainly recognition.

“That’s him,” she said, controlling Moonbeam with difficulty, “that’s Colonel Carmichael. Sean, you—do you know him?”

Sean’s expression went suddenly blank, as if he had pulled a mask over his face. “No,” he said flatly. His mouth was a tight, unsmiling line. “I don’t know him. When did I ever hobnob with colonels? I——”He managed a smile then. “Off you go, Deirdre, he’s looking for you to tell you ’tis time the Hares weren’t here. Do your stuff and sell him the horse. I’ll be keeping my fingers crossed for you!”

Abruptly, he turned his back on her and went limping across to his car.

Deirdre waited for a moment, looking after him uneasily. But he gave no sign that he knew she was there and Moonbeam was becoming harder to control, so, catching her breath on a sigh, she gave the grey his head and went, cantering over to meet Colonel Carmichael.

CHAPTER TWO

SEEN at close quarters, Colonel Alan Carmichael was younger even than Deirdre had thought him—thirty-three or four, perhaps—and not at all her idea of a retired Army colonel. He was neither red-faced nor blimpish but a very good-looking, rather grave young man, whose features were regular and strongly moulded, a trifle aquiline. His expression was as she remembered it from the glimpse she had caught of him in the car, austere and a little forbidding, and his eyes were a glacial, steely grey, but, as she came nearer to him, his mouth relaxed in a smile which banished the gravity and made him instantly more human and more approachable.

“Miss Sheridan?” He raised his cap. “I was told I’d find you over here. I gather it’s time we started.”

Acknowledging this greeting, Deirdre studied her new acquaintance, wondering why the sight of him should have upset Sean so much. For, despite his denials, she was convinced that Sean had been upset But there was no time to go into that now; the children were waiting in an eager, excited bunch, and they raised a cheer as the two Hares, the bean sacks slung loosely across their shoulders, cantered past

“We’ll give you ten minutes’ start!” the Pony Club Secretary called after them and sternly ordered his unruly pack of Hounds to turn their back so that the Hares might have their chance to slip off unobserved.

“Better put that copse between us, Miss Sheridan,” Deirdre’s partner suggested, “before we start laying a trait But”—he glanced at her over his shoulder—“I imagine you’ve got a course mapped out, haven’t you?”

Deirdre nodded. “Yes, I have. My father and I worked ft out together. We can start from the far side of the copse, though—that will delay them a little.”

From their temporary hiding place, she pointed out to him, roughly, the route they would take and Colonel Carmichael said approvingly: “Very sound. Some decent fences for the older children—and plenty of gates for the young idea. This is first-class training for them, but we don’t want any of them getting hurt, do we? Well, if you take the lead, PH look after the trail and be right behind you.”

“This way then,” Deirdre told him and touched Moonbeam with her heels.

For the next fifty minutes they made their way at a steady canter round the course she and her father had planned, stopping twice to give their horses a breather and once, at Colonel Carmichael’s suggestion, in order to lay a false trait

There was little opportunity to talk—once Deirdre called out a warning of wire and they halted, so as to set the trail safely away from it; on two occasions, as they jumped side by side, Colonel Carmichael complimented her on her horse’s performance. She knew that he was watching Moonbeam, approving of him: saw, too, that he was an accomplished horseman. Sir Henry Hollis’s chestnut wasn’t normally a spectacular jumper, but in such expert hands the old horse did all and more than was asked of him.

But after a while the pace began to tell and Deirdre saw her companion drop back, waving to her, quite cheerfully, to carry on done.

She did so, her light weight making little impression on the powerful Moonbeam, and with the ground rising steeply and the going deteriorating, she readied the end of her point and pulled up. Letting her reins fall on Moonbeam’s damp neck, Deirdre dismounted, to glimpse, from her vantage point, the first of her pursuers in a field two miles away. There was plenty of time she reflected, to give her horse a blow and wait for her companion to catch up with her before they set off on the shorter, homeward route back to the camp.

He was coming up the slope towards her, walking with long, easy strides and leading his tired chestnut, the reins looped over his arm. He smiled and pointed below to the little line of children on ponies, strung out along the false trail.

“We foxed them, Miss Sheridan! But by Jove, they’re going well — you can be proud of your pupils. Have we time for a smoke, d’you think?” He took out his cigarette . case and offered it, looking at Deirdre enquiringly.

She shook her head “I don’t, thank you. But you’ve got time for one, if you want it We can’t take the short cut back to the park until they’re past the spinney on the left there, or they’ll see us.”

“Right, I’ll keep them in sight — they’re heading for the spinney now.” Colonel Carmichael lit his cigarette, cupping the match between strong brown hands. Then his eyes went to Moonbeam. They were admiring, knowledgeable eyes. “That’s a grand young horse of yours, Miss Sheridan.”

“Yes.” Colour leapt to Deirdre’s cheeks. This was her cue but she hesitated, reluctant to play her accustomed part, with this man as protagonist, wishing herself anywhere but here. But what was the use of wishing? She was here and the supposedly unapproachable Colonel Carmichael was beside her, making overtures of friendship. She had done her job, given him a more than convincing demonstration of Moonbeam’s prowess as a jumper. Did it matter that her father had tricked him into coming with her? He was well off, he wanted a useful point-to-point horse — it would be madness to let slip this opportunity of acquainting him with the fact that Moonbeam was for sale. Her father was depending on her . . . and there was that dreadful overdraft.

She lifted her head and told him, stammering a little:

“Colonel Carmichael, I — if you’re looking for a horse, I mean — this one, Moonbeam, is for sale.”

Colonel Carmichael stiffened perceptibly. His smile faded and his tone was cold as he asked: “I see, but — tell me, do you always tout your father’s horses for him? Even on an occasion like this?”

“I” — indignation mingled with a sense of guilt put an edge to Deirdre’s voice — “I suppose you can call it that, if you wish to, Colonel Carmichael. I work for my father, whose business is breeding and training horses. And selling them. I’d heard you were likely to be interested, that was why I mentioned it. But if you’re not——”

“Oh, but I am interested, Miss Sheridan! Both in the horse and in your methods of salesmanship — they’re very effective. And, of course, I’ve heard of your father. I’ve heard a great deal about him.” The implication was deliberately offensive and Deirdre’s colour deepened. Before she could answer him he went on, his tone now brisk and businesslike: “I imagine it was his idea and not yours that I should take his place as Hare this afternoon? Oh, don’t trouble to deny it, it doesn’t matter. But I like the horse very much . . . so perhaps you’d better tell me what your father is asking for him?”

Controlling her temper, Deirdre told him.

“Oh!” His brows lifted. “That’s pretty steep, isn’t it?” He spoke curtly. Uncomfortably aware of her heightened colour, Deirdre returned, with equal curtness: “No, not for a horse like this. If you’re going to race at all, you——”

He interrupted her: “Miss Sheridan, I think you must have been listening to some of the exaggerated rumours about me. Most of them are untrue and I certainly don’t intend to be held to ransom on account of them! I’ve come here primarily in order to farm. If I do any racing, it’ll be for my own pleasure, and whilst I do intend to buy a horse or even a couple of horses, I’m not a rich man and I can’t afford to pay fancy prices for them. Er—perhaps you’d prefer it if we went on and finished our show for the children? I can haggle wth your father when we get back, can’t I? It scarcely seems the thing to indulge in acrimonious argument with a” — he bowed but he wasn’t smiling and his eyes were stern—“with a charming young lady to whom I’m indebted for an enjoyable afternoon and a most competent lead. So if you’ll forgive me . .

Deirdre was furious both with him and with herself, and anger almost always reduced her to speechlessness. What right had he to suggest that her father was—was——

She took a deep, uneven breath. “My father doesn’t ‘haggle,’ Colonel Carmichael Nor does he ask fancy prices. I don’t know what you’ve heard about him, but if you think he does, then you, too, must have been listening to exaggerated rumours! I’ve told you Moonbeam’s price. I’ve told you in case you should want him. You’ll find my father won’t reduce his price and I see no reason why he should — Moonbeam is worth every penny. I broke him in and I’ve hunted him, so I know he is!”

“You made a good job of him.” Colonel Carmichael conceded.

“Naturally,” Deirdre returned, with a flash of spirit, “I’d not ‘tout’ him if I hadn’t.”

The smile hovered again at the comers of his sternly set mouth. “My choice of words was perhaps unfortunate. I seem to have annoyed you, Miss Sheridan, and that wasn’t my intention, I assure you. If it’s any excuse, I was disappointed — having allowed myself to hope that you had sought my company this afternoon for its own sake — to learn that you had an ulterior motive for seeking it However, it’s possible that your father and I may be able to come to terms. I’ll call on him, if I may. But”—he pointed —“the children have reached the spinney. I’d better get up.” He swung himself expertly into the saddle and turned to look at Deirdre questioningly: “Shall we make our dash for it now?”

But Deirdre was not looking at him.

Paddy was galloping up the hill — an agitated Paddy, whose face was white and whose horse was lathered with sweat . . . Deirdre’s heart turned over.

Something must be wrong, dreadfully wrong, for Paddy to use a half-schooled four-year-old thus. . . .

“Paddy——” she cried. “Paddy, what is it?”

Paddy pulled up beside her, breathing hard. “Miss Deirdre thanks be to God that I’ve found ye!” There was panic in the old man’s faded eyes. He gripped Deirdre’s arm. “Tis the Captain, Miss Deirdre dear — ach, you must be brave, now! Marigold was after putting him down — ’tis a terrible bad fall that he’s had. Ye’d best come to him, I——”

“All right, Paddy, all right, PH come. But is he—Paddy, is he badly hurt?”

Paddy said, with a sob in his voice: “I don’t know. I don’t know, Miss Deirdre. I — I think he’s killed.”

Tears burned in Deirdre’s eyes, her throat contracted, so that she could not say a word. And then, from behind her, came Colonel Carmichael’s voice. It was very steady and reassuring.

“I’ll come with you. It may not be as bad as you think.”

Deirdre couldn’t speak but her eyes thanked him. With Paddy in the lead, they set off down the hill

A little crowd had collected in a comer of a wheat field, but none of the children was there and Deirdre was glad of this. Some farm hands who had been working near by had brought up a gate, removed bodily from its hinges. Deirdre could not see her father at first for the press of people about him, but she recognized Marigold, being led up and down by a boy in rough overalls. The filly was shivering, her glossy chestnut flanks covered with mud, her saddle awry and a leather broken. The boy spoke to her softly, but she was frightened and tugged at the reins he held, trying to get away.

Paddy swore beneath his breath. “Sure, she took that cut-and-laid at the roots, so she did — as if she didn’t see it”

He took her from the boy, and instantly she quietened. Paddy loved his horses, and even in that moment, when her brain was frozen and her blood turned to ice, Deirdre found herself approving of his concern for the little filly.