Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

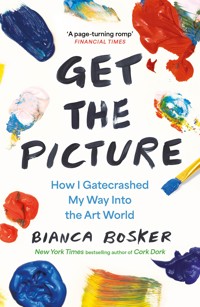

AN INSTANT NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER In Cork Dork, Bianca Bosker trained her insatiable curiosity, journalist's knack for infiltrating exclusive circles and eye for unforgettable characters on the wine world as she trained to become a sommelier. Now she brings her whip-smart yet accessible sensibility along for a ride through another subculture of elite obsessives. In Get the Picture, Bosker plunges deep inside the world of art and the people who live for it: gallerists, collectors, curators and, of course, artists themselves - the kind who work multiple jobs and let their paintings sleep soundly in the studio while they wake up covered in cat pee on a friend's couch. As she stretches canvases until her fingers blister, talks her way into A-list parties full of billionaire collectors, has her face sat on by a nearly naked performance artist and forces herself to stare at a single sculpture for an hour straight while working as a museum security guard, she discovers not only the inner workings of the art-canonization machine but also a more expansive way of living. Encompassing everything from colour theory to evolutionary biology, and from ancient cave paintings to Instagram as it attempts to discern art's role in our culture, our economy and our hearts, Get the Picture is a rollicking adventure that will change the way you see forever.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 587

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

GET THE PICTURE

Also by Bianca Bosker

Cork Dork

First published in Great Britain in 2024 by Allen & Unwin

First published in the United States in 2024 by Viking, an imprint of

Penguin Random House LLC

Copyright © 2024 by Bianca Bosker

The moral right of Bianca Bosker to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Some names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

Two-tone image on page 243 by Christoph Teufel.

Allen & Unwin

c/o Atlantic Books

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

Phone: 020 7269 1610

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com/uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Designed by Amanda Dewey

Hardback ISBN 978 1 91163 046 3

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 91163 047 0

E-book ISBN 978 1 76087 227 4

Printed in

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my parents

CONTENTS

THE HEADS

An Introduction

I.

THE MACHINE

II.

THE DANCE, DANCE, DANCE

III.

THE STUDIO

IV.

THE VACUUM

THE OPENING

A Beginning

Acknowledgments

Selected Bibliography

Index

The Heads

An Introduction

To be fair, everyone warned me it was a bad idea. What I wanted to do was not only impossible but vaguely dangerous, they intimated. They didn’t come right out and threaten my safety or anything. My reputation, well-being, and livelihood as a journalist—that, however, was another story.

It’s not like I was trying to expose CIA spies or anything. I was dead set on infiltrating what turns out to be a nearly as paranoid group: the art world.

I’d gotten obsessed with understanding why art matters, if it does, and whether quality time with a few smears of colored rock on stretched cloth—a “painting” as it’s more commonly known—can really transform our existence.

And how better to find out, I figured, than by handing myself over to the culture fiends who live for art: Artists who hyperventilate around their favorite colors. Up-and-coming gallery owners who max out their credit cards to show hunks of metal they think can change the world. I wanted to study the fanatics who fly their art with them on vacation and see if I could feel fireworks when I looked at art—instead of, as was often my experience, the urge to holler at the artist to just tell us what you mean.

Except as practically everyone in the art world saw it, what I wanted—this is where the warnings came in—was to stick my nose where it didn’t belong. “You’ll make some powerful enemies,” warned a seasoned art collector. “It’s not worth it for you living in New York.” Then an art dealer volunteered that he’d have no qualms trashing my reputation—personal, professional, and psychological—if I wrote anything he disagreed with. Nice career you’ve got there—be a shame if something happened to it.

IN RETROSPECT, I blame my grandmother’s carrots. I’d never have gone poking around the art scene if it wasn’t for them.

There I was: Early thirties, living in New York, with a nice career in journalism and a flawlessly optimized routine, albeit one that didn’t make room for art. And yet once upon a time, art had been my thing. Growing up in Oregon, I was a sun-starved little weirdo who painted obsessively, showed art in local shows, and flirted with applying to art school. I had it all planned out: I’d move to New York to squat in an East Village loft with my painter-lover-muse, who’d feed me cigarettes for breakfast and poetry for lunch.

Then serious Bianca grabbed the wheel. In college I took econ—never art history—with an eye toward the kind of career that would come with a dental plan. I graduated with a vague hope that I’d become an art appreciator if not an art maker, which lasted until I moved to New York and actually started seeing art on a regular basis. Whoa, was I out of my league. My first trip to galleries in Chelsea left me with the distinct impression I’d wandered into a private party by mistake. Pretension hung in the air like an unacknowledged fart, and at each show, I felt two tattoos and a master’s degree short of fitting in. I went to museums, which seemed friendlier, yet as I wandered through halls of oil-painted nobles and brooding marble statues, I felt overwhelmed by everything I didn’t know—the people, the periods, the -isms. Whatever love of art I’d felt shriveled in comparison to the bewildering feeling that I was woefully uninformed and thus doing it wrong. As the years passed, my visits to art shows became dutiful, and I let friends drag me along while I fidgeted awkwardly in front of exhibits I didn’t understand. Bit by bit, art and I became estranged. Eventually, we were no longer on speaking terms.

Then, a few years back, I was home in Oregon purging my mom’s basement when I yanked open a drawer of yellowed papers and my breath snagged in surprise. There, with their delicate black commas for feet and green whirling-dervish stems, were my grandmother’s dancing carrots.

My grandmother made a point of telling me the carrots’ origin story whenever I visited. My grandmother—this is my dad’s mom—was a twentysomething Jew in Warsaw when Hitler invaded Poland. By the time she was my age, she’d lost relatives to mass graves, narrowly avoided concentration camps, and been forced to labor in Soviet coal mines. She ended the war in a displaced-persons camp in Austria, where, though she was an economist with no children of her own and no artistic inclination that I know of, she started teaching art to the kids. Once, as a special occasion, she helped them organize a dance show, scrimping paper to make costumes, which had to be cheery but politically innocuous: She rejected apples (red could suggest Soviet sympathies) and birds (which could evoke bombers) in favor of carrots (which still got her interrogated by some overzealous official). She ended up in Illinois, where she worked long hours selling suitcases at a small shop in Chicago and spent her days off at the Art Institute collecting postcards of impressionist paintings she kept in old shoeboxes. In her eighties, after she retired, she picked up painting. One of her most treasured pieces was a watercolor she’d made of three skipping carrots that hung above her kitchen table until she died.

I’d forgotten all about those carrots, but now their prancing feet kicked loose a jumble of memories: afternoons with my grandmother sketching still lifes, our shared love for Seurat, a time when life felt limitless. I remembered sitting for hours in her kitchen studying the graceful swing of the carrots’ bodies while she described the art classes she’d taught in the camp, then proudly read aloud letters from her former students, who kept writing to her sixty years on. I never thought to ask her why she’d felt a pull toward art. The way she held forth on the carrots didn’t leave room for questions: Art simply wasn’t optional, or a luxury, but a necessary part of life. I felt a sharp stab of regret that I didn’t know the feeling.

I stuffed the carrots back into the drawer, but those sneaky vegetables followed me back to New York and trailed me around as I settled back into my routine. The carrots stomped their feet when I ate takeout at my desk. They crossed their arms when I texted from the toilet while listening to podcasts at 2x speed. Their wagging orange heads insisted that something was missing, that my life was dull dull dull compared to what I’d once imagined it could be. While I tried to answer emails, they danced my mind round and round the puzzle of why my grandmother had treated art, arguably the least essential thing, as essential—what she turned to when life turned itself inside out. I couldn’t shake the carrots. Worse, I couldn’t shake the sense that my predictable, ruthlessly optimized life had started to feel maddeningly claustrophobic. The carrots stirred up an idea: What if art could stop the walls from closing in?

MODERATION HAS NEVER been my strong point, and once I got the itch for art, I cannonballed in. I thought art might inject beauty into my blah routine—“wash away from the soul the dust of everyday life,” as Picasso supposedly said it could.

My awakening was rude.

I know I’m not supposed to admit this, but between you and me, a lot of the art I saw was barely recognizable as art. In the hushed halls of a renowned art museum, I beheld a giant stuffed bear with horns and a nose ring, and felt my heart go out to a mutilated chair. I spent a particularly disorienting evening at Bridget Donahue, a Lower East Side gallery my detective work had revealed to be the womb for all things cool. At the gallery’s opening, I squeezed past neckbeards and ironic tube socks to squint at a plasticky black seagull dangling ankle-height on a string. “Alcohol helps,” volunteered a guy next to me. (It didn’t.) I stayed long enough to catch a performance by the artist—a burly, middle-aged man who padded out into the gallery in a Snow White costume, climbed halfway up a metal ladder, and started mumbling into a microphone about an “animatronic goat trapped in an inflatable bush of cooked pubic hair.”

I don’t know what else to tell you about the art. It was there. I was there. I knew enough not to utter the two phrases guaranteed to brand me a lowbrow loser (“But is it art?” and “A five-year-old could do that”). But beyond that—I stared at it and got nothing but the familiar feeling that everyone got the punch line except me. I mean, was art just whatever people with expensive graduate degrees said it was? What made it good? Were those stupid questions? What did these geniuses nodding thoughtfully at the world’s worst Snow White impersonator know that I didn’t?

I stalked artists on Instagram, scoured art blogs, subscribed to every newsletter I could find, and forced myself to make small talk with strangers at art openings. I went to art talks, art shows, art museums, and art galleries (which is a fancier way of saying art stores). I hit up every remote acquaintance vaguely connected with art to catch up over coffee, then pelted them with questions. But all over town, the art refused to speak to me. It sat there, smug and withholding, whispering an inside joke to everyone but me.

Try a simpler hobby, I encouraged myself. Bake bread. Pickle. And it was tempting, really it was, only I couldn’t stop thinking I had to be missing out on something major because the art I was seeing inspired such extremes of devotion—on the part of not only viewers (who’d do things like hock a car to buy a painting) but also the artists themselves. I knew artists had a centuries-old reputation for being masochistic obsessives who’d sell a kidney for a tube of paint, but that looked relatively painless compared to what I was witnessing. I met artists who skipped meals, sleep, surgeries, having kids, seeing dying parents, and putting a roof over their heads in order to pour every last drop of themselves into making their work, with no end in sight except the art itself. “Our relationship ended because he was really concerned about the future of our finances and I was really concerned about the future of my paintings,” said one painter, who had uprooted her life in Georgia to move to New York—not for a lover or a job or friends but because, as she put it, she “wanted to be where all the paintings were.” Most artists I met were working at least two jobs, and their art lived better than they did, sleeping soundly in the studio while they woke up on a friend’s couch covered in cat pee. And for what? Beyond the handful of acquaintances they convinced to come to their studios, their art rarely got seen. They had to do mental math to decide if they could afford a bagel, and the advice they got was to “give up now.” Yet they kept giving everything they had to make objects that were supposed to show us something, communicate something, do something. And it drove me crazy that, despite a long relationship with art and a very expensive education, I couldn’t clearly discern what that was.

I’d never met a group of humans willing to sacrifice so much to create something of so little obvious practical value. With all due respect to my grandmother, I’d always thought of art as a luxury—I mean, it can’t clothe you, feed you, or be used to kill predators. But when I asked artists why they made art, they made it sound like I’d asked them why they eat food. “There’s, like, zero other choice.” Or: “It’s just natural, like how I have black hair.” And: “Because I feel like if I don’t pay attention to that, it will kill me.” Being an artist wasn’t a choice, it seemed. As a sculptor friend-of-a-friend told me over dinner one night, “The people who are canonized—it’s not because they’re great artists but because it’s life or fucking death for them.”

You might be thinking that all sounds a bit much, but then you, like me, might be surprised to learn that scientists are right there with artists in insisting art is fundamental to being human. Art is one of our oldest creations (humans invented paint long before the wheel), one of our earliest means of communication (we drew long, long, long before we could write), and one of our most universal urges (we all engage with art, whether preschoolers, Parisians, or paleolithic cave dwellers). I began to notice that art—or what scientists dispassionately call “human-made two- or three-dimensional structures that remain unchanged”—was everywhere: hung over the register at the hardware store, spray-painted on a bakery window, cockeyed in a dive-bar bathroom. As humans, we’ve filled our lives with art since practically forever. The earliest known painting keeps getting older, but the last time I checked, archaeologists had traced the oldest portrait to a cave in Indonesia where, around 45,500 years ago, artists put their finishing touches on a fat figure with purple testicles for a chin. In other words, before Neanderthals went extinct, before mammoths died out, before we figured out how to harvest food or heal bloody wounds, humans applied themselves to painting the portrait of a warty pig. “It is clear that the creation of beautiful and symbolic objects is a characteristic feature of the human way of life,” wrote the biologist J. Z. Young. “They are as necessary to us as food or sex.” I, for one, didn’t feel the necessity of art in the way I felt my stomach growl for a juicy burger. But reading that only made me more curious to experience whatever soul-rattling epiphany supposedly lurked in a sculpture of a dirty mattress.

I kept trekking to art shows, hoping to be moved, and while the art didn’t do it for me, the humans around it fascinated me. Like people who join cults or travel to space, art connoisseurs had the peculiar aura of the transformed. They’d seen things. Things that would blow your mind. Whatever it was had to be some heady stuff, because their reality bucked all the usual laws of nature. People held vicious grudges against the color blue or got breast implants and called it artwork. They got really excited about being really uncomfortable and took classes on pretending to be sequins. These artists frowned on my idea of beauty—there was beauty, one insisted, in a grotesque medley of chopped dildos glued to a canvas. More than that, they insisted my search for beauty was pitifully off base. “Beauty is my fucking nemesis,” spat a sculptor in one of many lectures I’d get on the evils of the b-word. They also had very different ideas about what was a valuable way to spend one’s time. “A big part of my practice at home,” said one, “is examining the garbage there and both being repulsed and inspired by it.”

It was thrilling. Or maybe it was bullshit? Either way, my life looked drained of color by comparison. My days were efficient. Theirs seemed expansive, like they’d accessed a trapdoor in their brains. Should I live that way? Could I?

Art connoisseurs insisted I couldn’t afford not to. They pitied me: They said I lacked “visual literacy,” which they swore was downright dangerous in a world so saturated with pictures. After all, there’s probably no time in history when we’ve been inundated with so many images. In the Middle Ages, we might have stared at the same pained portrait of Jesus on a church altar week after week, year after year, but now images crowd us when we check Instagram, throw themselves in our paths from billboards, and leer at us from packs of frozen peas—all hoping to exert influence. The people I was meeting worshipped the idea of an “Eye,” by which they didn’t mean the organ, but a painstakingly cultivated outlook that allegedly enables you to see lots that doesn’t meet the eye, like who’ll be the next Picasso or what’s transcendent about a middle-aged man climbing up a ladder to lecture about burnt pubes.

I hit the books. I read memoirs, investigations, biographies, and histories. I learned that art museums evolved out of aristocrats’ palaces and that Piero Manzoni canned his own shit for a sculpture. But what I didn’t learn was why. Why bother with art? Everything I read started from the assumption that Art Was Important, and if I didn’t know why, too bad. “One of the best things about art is that it doesn’t have to appeal to everyone,” said one art critic dismissively in an article that maintained the problem with art isn’t that it’s too elitist but that it’s not elitist enough.

I took some comfort in the fact that I wasn’t the only person I knew who could rub two brain cells together and yet was baffled by contemporary art—as in, art made by artists living right now. (Though technically the words modern and contemporary are synonymous, the term “modern art” counterintuitively refers to older art—generally made between the 1860s and 1970s—whereas “contemporary art” refers to everything that follows.) I started to think someone needed to get in there and ask some fundamental questions about how art works, then explain it to the rest of us. And I started to wonder if that someone could be me.

I fired off emails to artists, gallerists, curators, and collectors, hoping to get schooled and then swept up in their passion. I was hungry to learn how to engage more deeply with everything from Rembrandt paintings to The Ren & Stimpy Show. Eventually, I’d reach out to a wider cast of characters: conservators, psychologists, neurologists, the lucid-dreaming guide at an artists’ retreat I attended. But I was especially curious about the obsessives who control the nerve center of what’s called “fine art”—a distinction I’d learn is as solid as mud, but a label that’s nonetheless applied to painting, sculpture, and other kinds of visual art of the sort you see celebrated at museums, galleries, auction houses, and universities. These fine-art fiends intrigued me because they play such an outsized role in determining which artworks go from obscurity to the pantheon of illustrious cultural artifacts. These are the people—the “Heads,” I’d been told they called themselves—who shape art history and, while they’re at it, shape us: our idea of art, who makes it, and why we should bother to engage. I waited excitedly to hear from them.

The response I got back was unequivocal: Butt out. Lots of people didn’t bother to reply at all. There were a couple of gallerists who emailed saying they’d be happy to meet, then ignored all my followups, never to be heard from again. A few brave souls sat down with me, but only on the condition that everything they said was off the record. “Honestly, any little thing could just end me,” said the owner of a virtually unknown gallery, who asked me not to mention his name. An artist, barely out of grad school, said she was scared to talk to me—of what, I wasn’t sure. I’ve done reporting in China, where there is a deep distrust of foreign journalists, not least because talking to one could get you thrown in jail. I’d had an easier time sniffing out answers in Chengdu than Chelsea.

Every once in a while, my Deep Throats murmured warnings that I should get out before it was too late. “Things that pass for ethical in the art world would be criminal anywhere else,” said one art dealer. People who’d spent their careers in the art world described it as a “big con,” “fucking horror,” “quagmire of shit,” and “the world’s biggest high school.” Scratch that: A gallerist who’d taught at a high school assured me his colleagues were way worse than high schoolers—“Their ignorance is nowhere near as entrenched.”

A word to the wise: Nothing gets a journalist’s undivided attention like hinting something is rotten to its core, then clamming up. It’s like seeing your neighbor whistling “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” while he pats down freshly dug earth and incinerates a pile of clothes. Um, yes, I have a few questions. I realize that talking into a tape recorder while a reporter lobs questions isn’t most people’s idea of a relaxing afternoon. But I found the fear, the reticence, the cageyness that seemed to pervade the art world bizarre. And tantalizing. Artists broke out in hives if you asked them to explain their work. Gallerists hid the prices, then refused to sell you a piece, even if you could pay for it. Curators turned a sickly green when you mentioned the words “general public,” and critics often wrote about the art in code. (“Indexical marks of the artist’s body” would be “finger painting” to you and me.) What happened to art being a “characteristic feature of the human way of life”? Why keep people out? Why keep me out?

I couldn’t stop wondering what secrets lurked behind the gleaming white walls. Were these gatekeepers trying to protect the sanctity of a singular spiritual oasis? Or were they just trying to hide the fact that these turtleneck-wearing culture peddlers were carrying out the world’s most audacious con? The more I was told to stay away from the art world, the more determined I was to get inside it.

I began to develop a plan. A pushy, you-can’t-be-serious plan.

BEFORE YOU GO any further, I feel obliged to offer my own warnings. I didn’t heed the advice to stick to the party line. I didn’t discover the joy of impenetrable art theory. I also didn’t come around to the argument, which I heard a lot, that explaining art will deprive it of its magic.

What I did do, over a period of several years, is disown my normal life and discover just how messy “fine art” can be. I attached myself to brush nerds, color lovers, Eyes, Heads, and artist groupies, and learned what keeps them up at night. I bled over canvases, lost patches of skin to a sculpture, and let a nearly naked stranger sit on my face in the name of art. I worked as a museum guard protecting a pile of dust and learned why scientists call art a “biologically essential tool.” I got drugged, dared, shamed, shushed, and befriended by art obsessives who treat paintings like vital organs and know how to find beauty where we least expect it. In the process I discovered another existence, one where the act of looking is an adventure.

Part I

The Machine

CHAPTER ONE

My plan was this: I wanted to go work at a gallery, the snootier and more influential the better. I know, I know—who did I think I was? “A normie philistine” (my prospective employers’ words) can’t just show up at an art gallery demanding a job—especially not in New York City. But I’d tried cracking open books and quietly lurking in the corners of galleries, and I’d gotten nowhere. I wanted to see art, not just stare in its direction; I wanted to develop an Eye. I knew from past experience that there was no substitute for learning by doing, and the all-consuming passion of the compulsive lookers who signed their souls over to art had me convinced: To get at the truth about art, I also needed to understand the art world—the throbbing jumble of genius, money, and love that the artists I spoke with nicknamed “the machine.”

By my calculation working at a gallery was the ideal first step since gallerists saw all parts of the machine. They scoped out artists, schmoozed collectors, and buddied up to museums. Best of all, a friend of mine who knew the international gallery scene assured me I was supremely qualified for an entry-level gallery-attendant role. “You have,” he said approvingly, “an excellent resting bitch face.” And yet for months I hit only dead ends. I spent the summer chatting to as many art pros as would meet with me, and after emailing half the population of Brooklyn—the epicenter of the city’s artsy and avant-garde—I finally managed to unearth some gallerists who weren’t allergic to talking to an unfamiliar journalist. After peppering them with questions about art, I’d gently steer the conversation to all the reasons I was desperate to work for them. I offered to get their coffee, dry cleaning, anything to get inside.

It was going about as well as an FBI agent wearing his badge to a job interview with the mob. The word spy came up more than once. I tried applying to assistant jobs I found online, with the idea that I’d explain the whole “spy” situation once they met me, but that was before a gallerist broke the news that even a “no-name artist” looking for an unpaid studio assistant would get a hundred applications, and any opening at a gallery would get approximately three times that many. No wonder no one wrote me back.

Then, a glimmer of hope: A woman who ran a cool gallery in Chinatown loved the idea of letting me come shadow her. There was talk of after-parties and learning to suss out which customers wanted you to be a little mean to them and how, in the art biz, “you’re kinda always trying to extract information, but, like, with a martini in your hand.” I emailed her about setting up a date. I followed up about setting up a date. I never heard a peep from her again.

But I did get an email from someone named Jack Barrett, who ran a gallery called 315 in downtown Brooklyn. The woman who ran the cool Chinatown gallery had apparently mentioned me to Jack, and Jack asked if I’d like to speak. I would. Very much.

I’d never heard of 315 Gallery, which says more about me than Jack, but when I mentioned his name, people universally sang his praises. He was a rising star who “saw through the bullshit,” had a “cool program,” and was not only “really sweet and nice” but also “in it for the long haul.” His gallery, an out-of-the-way spot for the in-the-know, focused on “emerging” artists, a polite euphemism for up-and-coming artists who you probably don’t know and may never hear of. Jack gave lots of artists their first chance to show in the city, which immediately piqued my interest. I was more curious to witness the convulsions of art history being born than to hear the romanticized myths of the conquering heroes, and Jack was exactly the sort of person who helped the Andys and Jean-Michels of today become the War-hols and Basquiats of tomorrow. Plus, Jack possessed one extremely attractive quality that set him apart from nearly everyone I’d contacted thus far: He was interested in meeting me.

I WENT TO SEE Jack on the sort of suffocating August afternoon when even the air rubs its sweat on you. His gallery was up a steep flight of stairs on the second floor of a slouching building in downtown Brooklyn that shared a street with Global Praise and Deliverance Ministries, Foye Princess Hair Braiding, Sako Amy African Hair Braiding, Diallo Nene Hair Braiding, Nu-Expressions Hair Salon, Top Nail Design, and—two horsemen of the gentrification apocalypse—a natural wine boutique and an Edison-bulbed café that didn’t sell coffee but farm-fresh specialty third-wave Colombian pour-over coffee.

I found Jack at an angular white desk overlooking his one-room gallery, dwarfed behind a giant Mac computer. He had dirty-blond hair, fawn-like features, and, though he was just shy of thirty, I would have carded him before serving him booze. He wore a mock-turtleneck over boxy pink pants and purple sneakers that snaked up his ankle like an orthopedic brace. I’d been told he was the most fashionable male art dealer, but to my untrained eye, his look reminded me of a toddler dressed for a moon landing. Clearly I had a lot to learn.

Jack leapt up from his desk to take me on a tour of his current show: five works by three artists, including an animatronic drum set that bashed itself rhythmlessly and a wearable shrine made of antlers, cinderblocks, marshmallows, and soil (not dirt, I noted—“soil”). We paused to contemplate a pair of gold-and-black lines that shimmied and swerved along one whole wall. This was, in Jack’s words, the artist Guadalupe Maravilla’s “wall-based piece.”

I stared at the artworks and nodded politely. My mind was a gaping black hole, a blank void of nothingness. It was precisely the type of art I didn’t get but wanted to.

Jack settled himself at his desk while I wedged myself behind him on a low gray couch jammed between a filing cabinet and a minifridge. I hadn’t figured out how to comfortably balance my notebook on my knee before Jack launched into a primer on navigating the New York art scene. “I really don’t like the whole sort of like cold Chelsea vibe,” he announced. He’d interned at a Chelsea gallery in college, an experience that must not have sold him on the art world because, after graduating, he’d opted to get a master’s degree in psychology and counseling instead. After grad school he’d been in a slash career phase—working in fashion showrooms slash at a friend’s start-up slash doing freelance photography—when a friend persuaded him to split the lease on a space and start putting on art shows. The friend immediately bailed for a job at a swanky gallery uptown, and in the four years since, Jack had basically run 315 solo—because, he said, “I don’t make enough money to hire someone.”

For the next four hours, I scribbled in my notebook while Jack rattled off facts and survival tips. Installation art was harder to sell than photography, which was harder to sell than painting, and abstract painting (which doesn’t aim to depict the real world) could be harder to sell than figurative painting (which, like “representational painting,” does aim to depict something real). Galleries typically split each sale fifty-fifty with the artist, which still didn’t come out to enough that Jack could work at his gallery full time. Like a lot of young gallerists, he juggled a classifieds’ section worth of side jobs—hanging other galleries’ exhibits, photographing their shows—and his gallery was only open from 12:00 to 5:00 p.m., a holdover from when, until recently, he’d had to jump on his bike and book it to the dinner shift at a South African restaurant nearby. Not that Jack was in it for the money—“If I could turn my space into a nonprofit space and still do what I do, I would,” he said. 315 was about community. “That’s the meaning of this space: It’s able to be a space where people can come and gather. Talk. Converse. Enjoy each other’s company. Meet new friends. Be exposed to new ideas.” Oh, and—no big deal—Jack thought the art he showed could change the world. “I think art has the ability or power to move culture, which I think actually really changes peoples’ lives.” He hinted, obliquely, at grand aspirations to shape art history, even as he emphasized that “maybe one artist that I work with over the course of forty years will, like, ‘make it’ kinda thing.”

I had the distinct impression that Jack was going places. He spoke about art with a blasé intimacy that suggested he’d mastered the rules, mapped out the hierarchies, and—despite his nonchalance toward fame and fortune—was doing his damnedest to crack into an elite group of gallerists who didn’t just push boundaries but leapfrogged them. I was a little surprised someone this cool could be so down to earth, but more than anyone I’d talked to over the past few months, Jack overflowed with practical advice. He also prickled with passionate intensity, like a cattle prod masquerading as a teddy bear. I didn’t want to leave. I was convinced I’d found the perfect guide for my journey into the machine.

I was starving, close to peeing my pants, and horrifically late to another meeting by the time I reluctantly cut Jack off, just as he was telling me to make it my job to go to ten openings a week, plus dinners and after-parties and after-after-parties. He pulled out his phone to check that evening’s openings. “Out at the party is where things happen,” he told me. “So you have to do everything and go see everyone.”

I took all this as an invitation to ask, as I was stepping out the door, whether I could maybe join him at some openings sometime. I definitely needed to see him again.

Jack smiled thinly and shook his head. He couldn’t be seen coming with “the enemy,” he said, sounding a bit bored at having to explain such a known fact. The writer, he clarified, in case I was confused. The pariah, he added. He waved it away as a joke, but my stomach flopped as his first word kept ricocheting around my skull. Enemy. Me. The enemy.

Maybe I should have recognized this as a warning sign. But I was desperate to get inside a gallery, consumed with curiosity over what Jack’s Eye might reveal, and out of options. So when Jack emailed me again to suggest, enemy status notwithstanding, that I should come help out at his gallery, I didn’t hesitate. When do I start? He texted me instructions to report to 315 in clothes I didn’t mind getting dirty: “I’ll put you to work.”

CHAPTER TWO

I had no idea what “work” I’d be doing, but my plan was to do it so superbly that Jack would ask me back again. One day of assisting was no guarantee of a second, plus there was my reputation to consider. Everyone I met, including Jack, had offered the same pair of contradictory caveats: There are so many art worlds, and the art world is so small. I took this to mean that the art world was unknowable, but you were not, so you’d better watch yourself. “The art world is built on reputation. It’s all what people think of you,” said a gallerist, a piece of advice that came out sounding more like a threat. My gut told me if I messed things up with Jack, another door was unlikely to open.

The Monday we were set to meet, Jack texted up a storm, liveblogging me updates on his pit-bull rescue and their leisurely afternoon swimming at a pool in Princeton, New Jersey. I took his chattiness to mean he’d put the “enemy” stuff behind us and, later that afternoon, arrived at 315 antsy with excitement.

Jack informed me I’d be helping him prepare the gallery so he could hang a solo show of paintings by the artist Haley Josephs, which was set to open in ten days. Any opening is a big deal, but this was an opening in September. I’m sure I stared blankly. “I think of the year as basically September to June, because that’s basically when the art world functions,” Jack explained.

New York’s art scene operated according to a predictable rhythm: An artist represented by a gallery got a solo show every two years, a show lasted four to six weeks, an opening lasted from six to eight in the evening, and the whole shebang ran on Jet-set Standard Time, where business hours are convenient only for the idly rich and the seasons are not summer, fall, winter, and spring, but Hamptons, Chelsea, Palm Beach, and Gala. Come June, said Jack, “everything decamps to the Hamptons”—including collectors’ routing numbers—and galleries reacted accordingly. If you aren’t an everything that decamps to the Hamptons (a landing strip of compounds at the outer reaches of Long Island, where a dozen eggs can run twenty-four dollars), you’ll have noticed galleries’ default summer art shows tend to be, well, sleepier: probably a group show, meaning they exhibit a piece or two from a handful of different artists, many of whom the galleries are showing for the first time to test the waters. (A solo show, as the name implies, features a single artist.) Jack’s August show, with the drums and shrine, had been a group show. But September! Galleries saved the big names, the big prices, the big splash for September. September was “the first day of school,” Jack stressed. “There’s an energy. Everyone’s checking each other out.”

I inspected the gallery to assess how I could help. The room looked drunk: The walls slouched, the floor couldn’t follow a straight line, and the wheezy air conditioner looked ready to pass out. Josephs had dropped off five paintings, which leaned against a wall. I’d have said she made bright paintings of glassy-eyed young women, as if Lisa Frank illustrated Children of the Corn. Jack said, “She’s a figurative painter” who is “taking you into these deep intrapsychic conflicts going on in people’s minds.” The animatronic drums and the antlered shrine that I’d seen on my first visit to Jack’s gallery were gone, though the enormous black-and-gold mural—ahem, the “wall-based piece”—remained.

White walls, check. Art, check. The place looked pretty much ready to go. Sure, the gallery was a little banged up, but then Jack had let on that money was tight. Bigger galleries could divvy up tasks among a cast of characters that included directors (who pick and sell the art), preparators and art handlers (who muscle the art into the gallery), registrars (who track the art’s whereabouts), archivists (who file documents for posterity), and artist liaisons (who cater to artists’ whims). Jack did all of the above and then some. He picked which artists to show, schlepped work from their studios, bought beer for the openings, sold the art, and photographed his own shows (saving him $150 a pop, easy, he boasted). He also brought home the gallery’s garbage to avoid paying for trash hauling (saving $60 a month). “Every little thing adds up,” Jack told me. “I do everything. That’s why I’m always doing shit.” Rent—$2,200 a month—was one of his bigger expenses, but I wouldn’t find anyone paying less, he scoffed, unless it was a shoebox.

Given all that careful budgeting, I figured Jack would take a less-is-more approach to Josephs’s show. Prepping the space would take us, what, an hour?

Jack, however, saw nothing but problems. I hadn’t been there ninety minutes before he flopped down on the floor, stared up at the ceiling, and ticked through our to-do list as anxiety crept into his voice. One of Josephs’s pieces—a painting, nearly eight feet tall and six feet wide, of a woman scooping honey-ish goo out of her vagina—would need to be restretched: The wooden bars that held the canvas taut were cockeyed, so the painting sagged (imperceptibly, to me) on one end. Jack also wanted to spackle one wall, repaint another, and build an entirely new wall from scratch.

What he actually said was, “I want to construct an architectural element in the space.” He and Josephs had been “talking about the impression of time,” and he wanted a temporary wall that’d divide the room in two so he could hang the paintings of younger-looking figures in the front and older-looking figures in the back. “When you enter the space, it’s like a bit of a pocket,” Jack said. “Interpret that as a womb, interpret that as nothing.” Jack left the gallery and practiced walking in and out a few times, to imagine how the show would look to visitors at first glance. The wall would have the added benefit of blocking the windows: “People love natural light, but it’s hard to compete with the stimulus.” Also, Josephs wanted to show nine paintings, which Jack worried would look cluttered—the official, rather porny, term was overhung. “The only reason I’m willing to have a lot of work in here is because of the wall,” he told me. The wall would allow each piece to have “its own plane.”

The number of walls I’d built before this was a grand total of zero. Did I understand why Jack asked me to insert myself inside the wall, once we’d joined four fiberboard slabs to form a solid, freestanding rectangle in the middle of the gallery? I did not. Did I immediately squeeze my body through a nonexistent opening so that he could properly close up every side of the wall? I did. My status as Jack’s assistant was too tenuous to debate the point, so if Jack wanted me in a wall, I’d do my best pancake impression and slide on in. Faster than you can say “OSHA,” I was sealed into the architectural element.

From the outside, the wall had looked like an oversized white matchbox. That vision would be my last memory of the outside world, I realized. My new home had four brown walls that grazed my shoulders and barely enough room to turn around. I could see the ceiling—at least my loved ones could drop food in, I reassured myself—but otherwise, it was a spacious coffin.

Then the drilling started.

A screw shot through the wall, its silver fang nearly piercing my right hand.

“Watch your face. Watch your—everything,” Jack yelled from outside, just a few seconds later than would have been helpful and—SKREEEEE!— a new screw shrieked through the wood at my eyeball. The walls around me trembled with the force of the drill. I felt like a cavity being drilled out by a dentist.

Trying to sound nonchalant, I asked Jack if he could please maybe give me a heads-up before drilling again, but, you know, totally no big deal if not. By way of response, a screw lunged for my ribs.

“What if this is just a hazing ritual for you, and I wasn’t going to put a wall in the show,” Jack shouted as I strained to hear if he was loading fresh screw.

“Ha!” I said. I waited for him to clarify that he was joking, then darted sideways as he shot a screw at my thigh.

I involuntarily thought back to my first moments inside the wall. “Alright, Bianca,” Jack had called from somewhere above me, “this is where your life ends.”

He was right. And I was thrilled.

JACK INVITED ME back after my first day, then again, and before the week was up, I had basically no life outside 315. We’d meet at the gallery at 10:00 a.m. or 1:30 p.m. or 6:00 p.m., depending on whether Jack had a freelance gig that day. Dinner was takeout from the sparkling new mall down the street, which we’d eat on Jack’s couch, the garlicky smell of my Chinese food mingling with acetone from the nail salon downstairs and cigarette smoke from Jack’s neighbor down the hall—an underground gambling operation, he suspected. Jack tried not to eat mammals and got a pained expression when I took a plastic fork. “This. Is. So. Wasteful,” he said, staring me in the eye, after a café put a plastic lid on his smoothie. We’d work through eleven or midnight: spackling, sanding, vacuuming dust, blasting Travis Scott or Erik Satie while Jack cracked open a beer and I scrawled notes in my notebook. I’d given him the standard journalistic Miranda rights—you will be recorded for accuracy; you have the right to go off the record; if you are on the record, you may be quoted. “Starting the recording? Okay!” Jack would say in the morning, sly smile on his lips, before launching into his diagnosis of an exhibit he’d been to see since I saw him last. He wondered whether my husband minded that I was never home. Beats me. I hadn’t had time to ask him.

I blew off writing deadlines to fix Jack’s printer and stood up friends to help him restretch Josephs’s canvas. “You have to live it and breathe it” was the advice I got from a Whitney Museum curator I’d met through one of the gallerists who wouldn’t hire me, and I was determined to go as deep as Jack would let me. Also, a few days at 315 had convinced me that the best way to learn as much as possible was just to put myself at Jack’s beck and call, since there was no telling where each day would lead. A trip to Home Depot would turn into a studio visit with a painter would turn into us back at the gallery till 10:00 p.m. while I updated 315’s newsletter and Jack dished art gossip, like the artist he knew who would only let people buy her work if they bought two pieces and donated one to a museum. (“Buy one, give one,” it’s called, or just BOGO, and if you’re an in-demand artist, you can set those kinds of rules.) I felt like Jack was offering me a crash course in contemporary art and I needed to do whatever I could to stay underfoot. I never knew when he would swerve from railing against puppy mills to dissecting a “masterpiece” by the artist Danh Vo he’d seen at the Guggenheim.

We were futzing around with the architectural element one night when Jack practically dragged me over to his computer to show me Vo’s work. I hovered behind him, preparing to have my mind blown, and beheld the masterpiece: a boxy television set balanced on a white minifridge balanced on a washing machine.

“It’s one of the best pieces I’ve seen in a long time,” Jack breathed, eyes glued to the computer.

I leaned closer to the screen. I could see how it’d be pretty mind-blowing if you were, say, unfamiliar with modern appliances, but as it happened I’d been using washing machines for years now.

I knew better than to say that out loud. What I said was, “Why?”

“Becauuuuseee . . .” Jack said, struggling to find the right words to capture the magnitude of his experience of the work. “It sums up the most poignant experience of his life! Which is his family leaving their home and relocating to Europe and the experience of cultural assimilation. Like him and his grandmother arrived in—I think it was Denmark? Fleeing Vietnam, following the war. The refugees and the people immigrating there were given these objects—a washer-dryer, a refrigerator, and this TV—as, like, ‘You’re now a part of this culture.’ They were given as gifts to refugees to basically help make their lives easier, but it was simultaneously this way of like—” Jack exhaled deeply. “It’s cultural assimilation,” he said, a note of sadness in his voice. “Like, moving to the capitalist West and being told, This is what we value, this is how you should live your life.”

How were you supposed to get that without a working knowledge of Vo’s biography and Danish immigration policy circa 1970? I wondered. I envied the thoughtfulness with which Jack opined on art and how moved he was by the piece. But I was baffled by how I’d ever come close to doing or feeling the same. Looking at the art was apparently a necessary but insufficient condition for “getting” it.

Jack, who genuinely seemed to share my concern that I was an ignorant rube, took a keen interest in my development, and I gratefully handed myself over as a lump of clay to be molded. “I have homework for you,” he texted one Saturday evening, followed by a link to the trailer for The Square, a satirical movie about contemporary art. Another day, his jaw unhinged and crashed to the floor when he discovered I hadn’t read the art critic Clement Greenberg’s essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.” “Oh, you’ve got to read Greenberg,” Jack babbled excitedly, with the caveat that “a lot of people hate him now because it seems very last century” and “all the people he wrote about were men” and while there is Marxist theory in his work, “it’s a bullshit understanding of it.” Jack showed up one morning with a stack of art books for me: Clement Greenberg, Calvin Tomkins, Nicolas Bourriaud, Art Since 1960. “Do you know what object-oriented ontology is?” Jack asked. Negative. Again: jaw, floor. “If you don’t know about object-oriented ontology, I’m not sure you can have a conversation about contemporary art.” (Object-oriented ontology: The idea that any animal, vegetable, mineral, or lamppost can have its own private existence, independent of and unknown to humans.) Jack’s pleasure reading at that moment was Kenneth Clark’s The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, which The Guardian had ranked number twenty-seven on its list of the hundred best nonfiction books but Jack dubbed “just an old white guy talking about nude portraits of women by straight white guys.” He wouldn’t dare read it on the subway or bring it under his arm to a gallery. “I don’t want to set that bomb off. You get chastised a lot in the art world.”

Hold up—I’d never taken an art-history class? Jack’s eyes bulged. “Without education or training, you won’t be able to comprehend a lot.” I got the sense that to Jack, looking at art without studying art history was like doing surgery with a butter knife: You were dangerously unequipped and someone was going to get hurt. Jack suggested I pick up Janson’s History of Art (1,200 pages; nine pounds), even though “art history is just the history of the creative white male.” Still, he promised that knowing art history would help me judge quality. “There is objectively better work, but you have to place it in the timeline of art history,” said Jack, who’d studied both art history and fine art at New York University. “You can’t trust your instinct. It’s influenced by mass culture. Your gut falls back on the safety of what’s accepted by society.”

Oh! And memes. Was I familiar with art-world memes? No? Jesus. I started getting daily roundups of Jack’s favorite memes, and he’d sometimes hijack whatever we were doing to sit on the couch scrolling through memes. “Do you know this meme format?” he asked, holding up his phone to show me a cuddly, smiling Gremlin (“Artist’s opinions at the opening”) juxtaposed with a fanged Gremlin chewing a glass bottle (“Artist’s opinions once they leave”). “Do you know this meme format?” He gave a frustrated gurgle. “Ughhh! There’s so much beauty to memes if you just know how the format works!”

It was a steep learning curve, but Jack was a passionate teacher, and I tried to be a model student. I signed up to audit an art-history class at Barnard and slogged through Relational Art on the subway, taking comfort in Jack’s confidence that there were concrete steps I could take to develop an Eye.

One afternoon, I’d just arrived at the gallery when Jack crooked his finger at me to indicate I should join him at Guadalupe Maravilla’s wall-based piece. I obediently trotted over. The two of us contemplated Maravilla’s lines—one black, one gold—that squiggled the length of one whole wall, as far down as the electrical outlet and up nearly to the ceiling. From left to right, the lines zigzagged like spiky shark’s teeth, then swooped up into graceful humps, then settled into rectangular notches like the crenellations of a castle wall.

I eagerly waited for him to hold forth on Maravilla’s artwork—Shrine for the Undocumented Children, I’d seen it was called, and a particularly timely piece given that the Trump administration was in the midst of separating families at the nation’s southern border. According to Jack’s press release, Maravilla was an immigrant from El Salvador who’d “devoted his artistic practice to raising awareness around the struggles of undocumented immigrants and asylum seekers.” The wall-based piece at 315 was similar to one that Maravilla had up right this minute at—long whistle—the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Finally, Jack broke the silence. “I don’t know how many coats of paint this needs.”

Alarm bells jangled in my brain. Paint? This? Nooooo, he couldn’t possibly. Maravilla’s wall-based piece—hadn’t Jack himself written this?—was a “tribute to children who were lost while journeying to this country.” It was also, need I remind him, art. Granted, I was new here, but I felt solid on the point that painting over someone else’s artwork was frowned upon. Even, I’d go so far as to say, actively discouraged.

Maybe this was the hazing ritual. Maybe I was supposed to put up a fight. I tried not to panic. I stalled for time.

“Sooo,” I said, as Jack rummaged through his storage closet for a fuzzy purple paint roller and a tub of Ultra Pure White paint, “is that Maravilla piece something that someone could have purchased?” Maybe the idea hadn’t occurred to him.

“They could,” Jack conceded. Actually, someone was interested in buying Maravilla’s piece, he clarified. Good thing I checked. I got that Jack wanted to repaint his wall so he’d have a plain white surface on which to hang Josephs’s work, but still, he couldn’t possibly want me to paint over a piece of art that he was in the process of potentially selling.

I had a flicker of doubt: But what would the person be buying, exactly? I’d heard of an auction house selling a Banksy mural on a surgically excised slab of wall, only Jack didn’t seem prepared to saw into his gallery’s wall.

Eventually, he seemed to grasp my hesitation. A site-specific piece such as this—meaning an artwork made for a specific site—could be sold as a set of instructions so it could be remade without the artist ever touching it, Jack explained. “The whole point is that anyone can execute it.” In a museum, in a Miami condo, in a hundred years when the artist is dead. Owning one of the artist Sol Lewitt’s site-specific wall paintings means owning a piece of paper, signed by the artist, with directions for how the work should be made to look (i.e., “Straight lines about six inches long, touching and crossing, drawn at random using four colors, uniformly dispersed with maximum density, covering the entire surface of the wall”).

Hold up: Meaning the artwork was not, in fact, the swirling lines Jack wanted me to cover with paint? What was it, then? I burbled with questions.

“Don’t ask so many questions,” Jack interrupted, as he thumped down the paint bucket. “There are things it’s better you don’t know.”

That shut me up. I listened as Jack rattled off an endless list of instructions on how to properly paint a white wall white. Then, determined not to violate Jack’s so-many-questions ban, I gingerly dipped the roller into the bucket of paint and pressed it against a patch of spiky humps Maravilla had drawn near the center of the wall. White drips rolled down the wall over the artist’s lines, like blood from a wound. With each swipe of white, I silently apologized to Maravilla.

While I painted, Jack contrasted his gallery to the deli down the block, where we stocked up on bottled water to avoid drinking the rusty stuff that flowed from his tap. “It’s not a traditional business model,” Jack said of 315. “You’re literally selling an idea. A discussion. It’s so different.”

We weren’t screwing together walls and hanging paintings. We were mounting ideas.

“The difference between me and another emerging space? It all comes down to the decisions I make to showcase, display, certain artistic practices,” Jack said. “It’s an idea. It’s also a way of looking at the world. It’s a style.”

EXCUSE THE STONER SENTIMENT, but have you ever looked at a white wall? Like, really looked? That wall and I communed. Ever notice the raised scars of dried paint drips? Or how paint morphs before your eyes, so it’s thick and shiny when it goes on (and you think you’ve finally—finally— done your final coat) but then—whoa!—the stuff underneath shows up again? Do not believe what you’ve heard: Watching paint dry is an adventure.

This could be the paint fumes talking, but as I lost myself in the expanse of Jack’s wall, I started to wonder why nearly every art museum and gallery wore the exact same uniform. It was as though city code forbade showing art anywhere except in hushed white rooms with surgical-grade lighting and squeaky floors. Turns out, that formula has a nickname—“the white cube”—and for centuries, it didn’t exist.

Back in the 1800s, New York’s galleries and art museums looked less like operating rooms and more like hoarders’ dens. Paintings weren’t hung on white walls, in single rows, at eye level. Paintings crawled up the walls. They hung at knee height and overhead; in columns of four; on flowery wallpaper below gilded cherubs. For a time, the go-to wall color in Europe’s museums was a grayish olive (“the most neutral of all the decided colors,” per an 1828 decorating guide), which then gave way to a dark maroon. (The most popular color for German museums in 1890 was a rich burgundy called “Gallery Red.”) The impressionists baby-stepped toward current conventions by adopting a fashion of spacing out their art and hanging it in single or double rows (mimicking the look of their studios), and a few decades later modernists were pushing white as the new neutral. But it was the Nazis who helped perfect what we now think of as the white cube. The Nazis’ first foray into architecture-as-propaganda was building none other than an art museum, which opened in 1937 with tall ceilings, spotless white walls, gleaming floors, sparsely hung art, and bright overhead lighting—a design ethos that failed artist Adolf Hitler praised as a brick-and-mortar manifestation of his quest for “cultural purification.” From then on, the look became so popular that, historian Charlotte Klonk observes, “one is almost tempted to speak of the white cube as a Nazi invention.”

You’d think with friends like these the white cube would be verboten, and yet for ninety years, it’s stuck and spread—and not because the white cube has been scientifically proven to be the optimal way of experiencing art. “The white wall’s apparent neutrality is an illusion,” writes the art critic Brian O’Doherty, who coined the “white cube” term. “It stands for a community with common ideas and assumptions.” O’Doherty argues that the white cube is effectively a mechanism for ensuring art is considered art—one that’s so powerful it can cause us to confuse mere stuff for artistic treasures. Case in point, Jack and I were out touring art shows one day when, while thankfully out of Jack’s earshot, I complimented a wall-based sculpture of a small metal knob protruding from a square hole. “This is a piece of the wall,” the gallery’s owner gently corrected. “But I will sell it to you.”

I was beginning to pick up on the hidden logic of my new surroundings. No detail was too small for Jack to fuss over, and as we spent endless hours trekking to the hardware store for joint compound or mending plates, I reconciled myself to the fact that before I could learn to analyze a painting, there was a lot I needed to decode about the elaborate ritual of presenting art.