Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

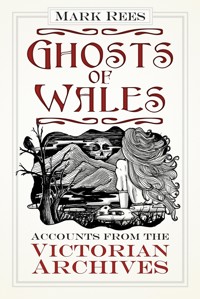

In the Victorian era, sensational ghost stories were headline news. Spine-chilling reports of two-headed phantoms, murdered knights and spectral locomotives filled the pages of the press. Spirits communicated with the living at dark séances, forced terrified families to flee their homes and caused superstitious workers to down their tools at the haunted mines. This book contains more than fifty hair-raising – and in some cases, comical – real life accounts from Wales, dating from 1837 to 1901. Unearthed from newspaper archives, they include chilling prophecies from beyond the grave, poltergeists terrorising the industrial communities, and more than a few ingenious hoaxes along the way.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 239

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

All illustrations © Sandra Evans except where otherwise noted.

(www.facebook.com/SandraEvansArt)

First published 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Mark Rees, 2017

The right of Mark Rees to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8607 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Introduction

One

Wild Wales

Two

Haunted Homes

Three

Talking with the Dead

Four

The Victorian Ghost Hunters

Five

Poltergeist Activity

Six

The Ghosts of Industry

Seven

Sacred Ground and Superstition

Eight

Paranormal Hoaxes

Nine

Weird Witticisms

Bibliography

References

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Rees has worked in the media in Wales for more than fifteen years as the What’s On editor and arts writer for the South Wales Evening Post, Carmarthen Journal and Llanelli Star newspapers, and Swansea Life and Cowbridge Life magazines.

During that time he has written and talked extensively on Halloween and paranormal subjects for the press, including conducting in-depth investigations into some of Wales’ most haunted places.

His first book, The Little Book of Welsh Culture, was published by The History Press in 2016.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing a book is a team effort, and Ghosts of Wales: Accounts from the Victorian Archives would not have been possible without the very kind assistance of everyone who helped along the way, starting with Nicola Guy and the wonderful team at The History Press who commissioned my investigation into the Welsh ghosts of the nineteenth century.

A huge diolch o’r galon goes to the amazing Sandra Evans, whose superb illustrations have made this book worth owning for the art alone. To see more of Sandra’s work, visit her Facebook page at: www.facebook.com/SandraEvansArt.

A collection of this nature would not have been possible without the invaluable service provided by those working hard in the newspaper archive industry, and my deepest thanks goes to everyone at The National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth and West Glamorgan Archive Service in Swansea.

I would also like to express my undying gratitude to my fantastic family for once again putting up with me during the writing and research of another book, and to everyone who has supported me on my publishing adventures to date, including: Jonathan Roberts and all at the South Wales Evening Post; Caroline Rees and all who made a success of The Little Party of Welsh Culture; Jane Simpson and all at Galerie Simpson; Kev Johns; Chris Carra; Owen Staton; Fifty One Productions; Rosie Davies; Mal Pope; Wyn Thomas; Pat Jones; the Heroes and Legends festival; Dan Turner and the Horror 31 gang; Simon Davies and all at The Comix Shoppe; Ian Parsons; Ronnie Kerswell-O’Hara; Swansea Fringe Festival; and Emma Hardy and Bolly the cat, who ensured that I always had enough pizza and wine to keep me going, and that I was always awake nice and early enough to get on with my research – even on my days off.

INTRODUCTION

Do you believe in ghosts?

Tell anyone that you’re writing a book called Ghosts of Wales: Accounts from the Victorian Archives, and that will be their number one question.

But it’s a question which I think is almost irrelevant when it comes to writing, or reading, a book of this nature. Regardless of our own personal beliefs – hard-nosed sceptic, true believer, or undecided and sitting on the fence – what makes the accounts contained in this volume so fascinating, and possibly terrifying, is that for the people who experienced them, seeing – as well as hearing, feeling, and in some cases smelling – really was believing.

Not that everything in this book is considered to be fact, of course – even if it was reported as such at the time. Some of the accounts were proven to be false, others are incredibly hard to take seriously, and there are those with no evidence to back up the claims besides the words of an untrustworthy witness.

But then there are those which are much more difficult to disprove.

There are accounts which were corroborated by multiple, reliable sources. There are some which were argued about in the courts of law. There are others which eerily forewarned of upcoming events which came to pass. And many of them are verifiable with dates and addresses, recorded testimonies, and hard-to-know details included.

I think a more appropriate question to ask, and one which is much easier to answer, would be ‘why the Victorian era?’

The Victorian era has been dubbed the ‘golden age’ for ghosts and spiritualism, in both fiction and the real world. During the nineteenth century, the likes of Charles Dickens and Edgar Allan Poe were sending shivers down readers’ spines with their tales of unspeakable horrors, while the Fox sisters kick-started an Atlantic-crossing craze for séances in America, and the Society for Psychical Research was established to investigate claims in a scientific manner.

Much has been written on these subjects already, but while the misers of London were being shown the errors of their ways by Christmastime spirits, and the great and the good were sitting around tables listening for knocks from beyond the grave, what I really wanted to know more about were the spooky happenings in my home country – while the world was going paranormal crazy, where were all the Welsh ghosts?

There was only one way to find out. I decided to roll up my sleeves and do some good old-fashioned research in the newspaper archives. And I was totally unprepared for what I would find.

Initially, I had hoped to uncover a few good reports. But the more I dug, the more I found. They just kept coming, and seemed to get better and better all the time. Before I knew it, an hour or two’s research to satisfy my curiosity become a day’s research, and then a week’s research, and then a month’s research, and then a year’s research.

What really excited me the most was that these were stories that I had never heard of before, and I was uncovering facts which might have gone unseen for more than a century. These weren’t the same old yarns which have been repeated endlessly, but new tales, to me at least, of dark séances in Swansea, a noisy White Lady on the streets of Cardiff, and mysterious premonitions ahead of horrific mining disasters.

It was then that I decided that, to do these stories justice, it would be a good idea to collate my research into a book. Fortunately, my publisher agreed, and I’m pleased to say the copy that you now hold in your hands is the result of that pleasant discovery one Halloween.

Rather than simply throwing a series of unconnected stories together, I have presented them in such a way as to form, I hope, a coherent narrative which will take the reader on a journey through the many aspects of supernatural activity and beliefs at the time. Because while this book might be a collection of ghost stories, it also serves as a tantalising glimpse back at Welsh society in the Victorian era, when the dragons and fairies from days gone by gave way to much more frightening things which went bump in the night.

As such, it has been divided into nine sections, which range from the more traditional ghost stories firmly rooted in the folk tales of old, to the more sinister accounts of violent poltergeist attacks on secluded farmlands. Some of the reports provoked heated debates in the letters pages, and others warranted multiple follow-ups, and where possible I have collected all of the available information together into a single article. I have also corrected any spelling and grammatical errors which might have been included in the original newspaper reports, and tried to remain consistent with the spelling of place names where appropriate – for example, Aberystwyth has been spelt in the Welsh way throughout, except when used in the title of a publication such as The Aberystwith Observer.

How many of the accounts in this book are true? I will leave it up to you, dear reader, to approach them all with an open mind, and to decide for yourself.

I hope you enjoy reading this book as much as I enjoyed researching it, and if any of the locations are familiar to you, who knows – maybe you could pop along and see if the ghosts still haunt to this day?

Mark Rees, 2017

1

WILD WALES

Do you believe in ghosts? Then attend to my story! But first draw round a good fire, and get company to keep your courage up. Laugh as we may at the idea of ghosts and witchery, people do believe in ghosts, and fear them.

The Victorian era was a time of unprecedented change, for the people living through such turbulent times, as well as for the popularity of ghost stories – in the world of fiction as well as in the real world.

During Queen Victoria’s reign, which ran from 1837 until her death in 1901, life was moving at a rapid pace. In Wales, the Industrial Revolution had seen communities transformed beyond recognition, with many leaving their traditional rural homes behind to find work in larger towns and cities. The country’s population boomed, and an influx of immigration brought with it new influences and ideas.

The Victorian era was seen as an age of rationality, scientific progress and innovation – the ever-expanding railways enabled people to travel far and wide, the telegraph and telephone allowed for communication like never before, and Charles Darwin published the world-changing On the Origin of Species in 1859.

But it did not do away with paranormal beliefs. Far from it, in fact. Much like Darwin’s theory they evolved and, if anything, became more popular than ever.

Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, considered to be one of the definitive ghost stories of the period, was published in 1843, and advances in the printed press saw a huge increase in demand for sensational spooky yarns to fill the periodicals. At the same time, stories which had previously been more of an oral tradition, such as the old Welsh folk tales of goblins and dragons, began to give way to modern explanations for unexplainable events – from now on, mysterious sounds heard at the dead of night were more likely to be attributed to the troubled spirit of a former occupant than a visit from the mischievous fairy folk, y tylwyth teg.

As we shall see in this book, interest in the paranormal was further bolstered by such factors as the rise of spiritualism, the conditions of living in crowded gas-lit homes, the new terrors which lurked deep underground in the mines, and more than a few practical jokers along the way, all of which played a part in keeping the supernatural firmly in the spotlight.

In this first chapter, we head out into the great outdoors to take a look at some of the strange occurrences which were reported in what are considered to be the more traditional haunted locations – the dark lonely forests, the dreamy romantic lakes, the grand old mansion houses, and the imposing mountains which combined to make up wild Wales.

The two-headed phantom

From Anne Boleyn to the Headless Horseman, spirits with severed heads have been a popular mainstay of ghost stories for centuries.

But in Abersychan in 1856, the opposite appeared to be true. The town’s unique ghost, which was said to be ‘haunting’ the vicinity of the Blue Boar public house, wasn’t missing his head – he had gained a second one.

The two-headed entity was described as having a ‘hideous appearance’, and had ‘stricken many of the inhabitants with great terror, especially those whom he has honoured with a visit, or thought worthy of a glimpse of its outline’, nearly driving one fearful local to an early deathbed.

In a newspaper report, multiple witnesses claimed that they could ‘minutely describe him’, and the believers in ‘ghostly mysteries’ put forward a theory as to his identity, as well as how he had managed to gain an extra head. As one resident explained:

It is the ghost of an old man who suddenly met his death by falling down stairs and splitting his skull. The old man, when living, was an apostate from the Roman Catholic faith, therefore, could not have rest in the other world; consequently, he is a wanderer upon the face of this one. The cause assigned for his appearing with two heads is, that his head being split when dying, could not again be reunited; therefore, they are not really two heads, but two separate halves of the once whole.

The sceptical journalist, unconvinced by this hypothesis, asks, ‘Is this the wisdom of the nineteenth century?!!’, adding somewhat disbelievingly that those living in the immediate locality are too scared to leave their homes after dark unless ‘some urgent necessity compels them’.

In the case of labourer Dan Harley, who is described as a ‘true believer in apparitions’, an urgent necessity did indeed compel him to stay out after dark one night and, as a result, he came face-to-face with the terrifying entity:

Being delayed from returning home until a late hour, he had no alternative but to pass the haunted spot, or to have a night’s parade in the chilly air. Not liking the latter, he determined to proceed despite his dread. He went on courageously until within a few yards of his lodging house, when he fancied he could see something – he paused, and lo! it was no less than the dreaded phantom. He could not speak: neither could he move backward nor forward – he remained transfixed to the spot for several seconds, but as soon as he thought the spectre was disappearing, he made a desperate effort, and reached the house, wherein he repeated undefinable prayers to his preserver. His feelings for the remainder of the night can be imagined better than described. It is certain that he did not enjoy much rest, for he says that he was ‘covered all over with fright’.

The next morning, Dan attempted to go to work as normal, but the event had proven to be too traumatic:

On his way he sat down in a fainting state, the fright all over him still. At that time his fellow workman Patrick King happened to come by the place and, seeing his fellow comrade in such a weak state, assisted him home. For several days poor Harley was in a very desponding state. For some time he thought he was going to die, and under that conviction he wished his friends to give to his friend Pat Ring, after his death, the portrait of Ellen, his old sweetheart, which he held in great veneration; also his big pipe and his backey pouch.

Fortunately, he soon recovered – and kept hold of his possessions for a little while longer – but remained convinced of what he had seen that night:

When he is spoken to now respecting his boasted courage, he says, very seriously, that he never was afraid, nor never will be afraid of all the ghosts of the earth or of the spirits of the air; but that such a two-headed monster was enough to put the dread on any man, and no man could help it, and ‘Be jabers, I hope it may be the last I may ever see of the lad.’

A wild night by the romantic lakes

The following recollection of a ghostly encounter published in 1895 is an interesting story in and of itself, but what makes it potentially even more interesting is the name attributed to it: W.G. Shrubsole.

While the article does not give any further details as to the author’s identity, the Victorian landscape painter William George Shrubsole was known to have been working in Wales during the period, having relocated to Bangor in the 1870s, and his choice of words, as this introduction illustrates, would perfectly fit that of somebody in search of inspiration from the rugged landscape:

I had been staying during the autumn of 188– at a cottage situated on the shores of one of the most romantic lakes in Wales. I grew so charmed with the place that I prolonged my stay until the beginning of December, and was amply rewarded by the wild beauty of effect which the scenery around ever presented.

Little did he realise that, by extending his stay, he would see not only more of the country’s wild beauty, but also something of a much more otherworldly nature. The following events, as recalled by the writer himself, took place towards the end of his visit:

On a moonlight night, I became the observer of what to me at the time seemed a strange, but by no means supernatural, manifestation. It was only by the light of what I afterwards heard that my experience assumed the complexion of the supernatural, and as at the time I was unexcited in mind, and not in expectation of any manifestation from another world, I am plunged in difficulties whenever I attempt to account for it by natural causes. Had my mind been in a state of highly wrought tension, I could easily account for the vision, by relegating it to that class of sensory illusions to which we well know mankind is susceptible, and of which I myself have had, on more than one occasion, very striking examples.

Well, then, one evening after supper, at the close of a very uneventful day, I took a walk as far as the end of the lake and back. This was a very ordinary thing for me to do, and on the occasion in question, I lit my pipe, and with a stout stick in my hand, wended my way along the side of the lake, my only companion being a large dog belonging to the house. It was blowing up for a wild night, and now and again a gust swept down from the hollows of the hills with a violence that made me pause in my walk to steady myself and caused the surface of the lake to be whipped into temporary commotion; the moon shone fitfully through the driving clouds and ever and again there came a soughing from the towering crags around, strangely wild and human, as if the spirit of the wind were mourning amongst them.

At last I reached the end of the lake, and giving a long look behind the dark dreary moorland, turned to retrace my steps towards the cottage. For some time I made rapid progress homeward, noting the wonderful way in which the patches of moonlight chased each other up the side of a steep mountain on the opposite side of the lake, until I was nearly half way back to the cottage. At this spot the road formerly went round a point of land jutting into the lake, covered with huge masses of rock piled high one above another. When I reached this place the moon became densely overcast with clouds, and it suddenly grew so dark that I could scarcely see the wall on each side of the road.

The dog was some few yards in advance, and I called him, intending to stop for a minute in order to fill and light my pipe, hoping, too, that the clouds would soon break again. But the dog, instead of returning to my call, gave a short howl, which, a few moments later, I heard him repeat at a greater distance. He was evidently making for home as fast as possible, and I concluded that he must have trodden on something and hurt or cut his foot. Leaning against the wall, I struck a match and shielding it with my body and hands from the wind, succeeded in lighting my pipe, and then again the moon began to break through the clouds, and I paused for a few seconds to watch the light stealing across the water.

Suddenly below me at a few yards distance I saw the figure of an old man, his hair flying in the wind as he stooped forward to lean upon the handle of a spade or mattock. I was startled, for the old fellow came so suddenly into view that it seemed as if he must have dropped there from the clouds. I hailed him with a shout of ‘A wild night this’ – he gave no reply, but slowly turned his face up towards mine. The moon gleamed out brightly for an instant, and I saw a pair of hollow, sunken eyes set in a face so full of a kind of weary despair – of a hungry disappointment – that I was shocked, and for a moment I had a slight feeling that there was something ‘uncanny’ in the appearance of this old man at such a time. What could he be doing there? But I had no time to lose; it was getting late, so with a ‘Good night’ shouted in the local vernacular I turned towards home once more. A few paces further on I looked back, but the old fellow was gone – had probably moved into the shadow of, or behind some of the rocks.

Putting my best foot foremost, I soon reached the cottage and found the kitchen tenanted by three or four people from neighbouring farms. ‘Dear me! Mr —,’ said the good woman, ‘We have been quite anxious about you, sir, since Tos came in without you. Something seemed to have frightened him.’

‘Oh! I am all right,’ I replied with a laugh. ‘By-the-bye, can you tell me who the old fellow is I saw along the shore of the lake with a spade?’

I shall not forget the effect of my simple query. Every eye turned on me with a ghastly stare, the men turned pale, and the woman sank into a chair. One of the men turned to another and in accents that seemed dry and forced said: ‘He has seen the digger of Fotty.’

Then their tongues were loosened and a Babel of Welsh arose. In vain I tried to understand what they were saying. I could only catch a word here and there. But they soon departed after many pitying glances at me and much ominous shaking of heads.

Then I learnt the cause of this commotion – I had seen a ghost! The figure of the old man was that of one who had died several years back. During his lifetime he had been remarkable for the penury of his habits, and was said to have on more than one occasion taken the most relentless advantage of people in monetary difficulties; his greedy and miserly habits became a monomania, and this, at last, assumed the form of a hallucination that there was a vast treasure buried at ‘Fotty’ – the place where I saw him. At all hours the old miser might be seen there digging in different places in spite of wind and weather, and he would often be heard muttering colloquies with someone he seemed to imagine was at his elbow, so it soon got reported that he was in league with the fiend, and he was avoided and detested by the neighbours more than ever in consequence.

At last, one stormy day, a fisherman found the old man’s dead body at ‘Fotty’ with his spade still grasped in his hand. The discoverer ran in alarm to the nearest farm-house to inform the people of the miser’s death, and a party of men soon made their way to the spot where the fisherman had left the body; but it was gone, spade and all, and never a trace of it was seen again. Sometime after, what was stated to be the handle of the old man’s spade was found in an almost inaccessible hollow of the neighbouring mountains, so it became accepted as Gospel truth that the fiend had carried away the miser’s body over the mountains and dropped the spade in the transit. After this a farmer returning home late one night was frightened almost to death by seeing what he took to be the spirit or the miser, spade in hand, at work on his favourite spot. The story got abroad, again and again it was verified, the ghost of the old miser from time to time appeared to several, and seemed to be, as a role, the portent of the direst calamity to each individual who saw it.

This was the story as I received it, and its truth was corroborated by many people living in the locality. Had it been told me before I saw the figure by the lake, I should have simply thought the apparition the figment of my imagination; but at the time I saw the old man, I knew nothing of him or his history, so I cannot account for the vision by any process of reasoning, and I am driven to the conclusion that as Shakespeare says: ‘There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in our philosophy.’

The haunted hiding place

Plas Mawr, Conwy by Arthur Baker (1888).

A room in Plas Mawr, ‘one of the most perfectly preserved specimens of Elizabethan manor houses now existing in this country’, made the headlines in 1893 following the report of a haunted room.

The recently formed Royal Cambrian Academy of Art, an institution for the visual arts in Wales, had based itself at the property in Conwy which contained ‘numerous low, oak-panelled, and oak-floored rooms, filled with an excellent collection of oil and water colours, of which the critics speak very highly’.

It drew many visitors to see the art and architecture, but after the publication of the following account, people were soon visiting to see another of its attractions – a ghost.

A member of the public got straight to the point when he brought the haunting to light in a letter to the press:

I wish to make public – for the first time, I believe – an attraction that one almost instinctively looks for in connection with such an old house as Plas Mawr, and that is ‘A Haunted Room!’ There can be no doubt about it, for I have the story from one who is both an eye and an ear-witness of the fact that one of the rooms in Plas Mawr is haunted.

He explained that the story had been related to him by one of the Royal Cambrian Academy of Art’s officials who, on finding the narrator and his companion exploring a particular part of the house, introduced himself with the enticing opening line, ‘Ah, you are studying the haunted room, are you?’

At first they laughed, but the official continued, relating his first-hand experiences at the premises:

‘Very few people know it,’ he said, ‘but it is a fact, and it is supposed to have some connection with the priest’s hiding place, which is just here,’ he added, tapping the wall between the door of the room and the huge fireplace.

We were delighted, and explained that we had not heard of the priest’s hiding place any more than we had of the haunted room, and begged of him to let us see the interesting secret recess in which, perhaps, some poor recusant had hidden himself in the stern times of Good Queen Bess.

‘Come this way,’ he said, and advancing to the corner of the room, he tapped the apparently solid wall. We expected to see the wall open, revealing a dark cavity, but nothing happened, and somewhat disappointed, we listened to our guide’s explanation that ‘the hiding place lay behind the wall.’

He led the pair through two rooms and up a flight of stairs where a ‘small worm-eaten door’ led to a low attic. They were warned to follow in the guide’s footsteps exactly, ‘otherwise you may crash through the ceiling of the room below,’ and he directed them towards the attic’s top right-hand corner: