Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

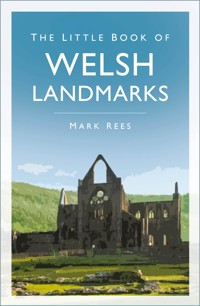

Did you know? - The Wales Coast Path is the only continuous footpath in the world that runs the entire length of a country's coastline, a staggering 870 miles. - Wales is home to the largest concentration of medieval castles in the UK, with four iconic castles – Caernarfon, Conwy, Harlech and Beaumaris – designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. - St Davids, home to an awe-inspiring cathedral surrounded by Pembrokeshire's rugged coastal beauty, is Britain's smallest city. - Laugharne, with its stunning views of the Tâf Estuary, inspired Dylan Thomas's Under Milk Wood, written in his iconic Boathouse and Writing Shed. From the towering peaks of Snowdon (Yr Wyddfa) to the stunning Wales Coast Path, this captivating guide takes you on a fact-filled journey through Wales's most iconic landmarks. Discover the country's rich history at breathtaking World Heritage Sites, the UK's first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, legendary castles and sacred cathedrals. Step into the world of Welsh folklore as you explore secluded beaches, mystical rivers, and ancient landscapes tied to the myths of King Arthur, the Mabinogion, and other timeless tales. Whether you're exploring Cymru for the first time or rediscovering its wonders, this handy book offers fascinating insights into its culture, heritage, and the secrets woven into its legends.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 241

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2018

This paperback edition published 2025

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Mark Rees, 2018, 2025

The right of Mark Rees to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 024 0

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

CONTENTS

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty

2 Wonders of the World

3 The Seven Wonders of Wales

4 Climbing the Highest Peaks

5 Getting Back to Nature

6 Coastal Treasures

7 A Land of Castles

8 Spectacular Spans

9 Living in Style

10 Religious Miracles

11 Forged by History

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

For more than fifteen years, Mark Rees has published articles about the arts and culture in some of Wales’ best-selling newspapers and magazines. His roles have included arts editor for the South Wales Evening Post, and what’s on editor for the Carmarthen Journal, Llanelli Star and Swansea Life. His other books for The History Press include The Little Book of Welsh Culture (2016), Ghosts of Wales: Accounts from the Victorian Archives (2017) and The A-Z of Curious Wales (2019).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank everyone who has helped me on my journey in search of Wales’s finest landmarks. In particular, a huge diolch o galon to my family for supporting me on yet another crazy writing adventure, and to Nicola Guy and everyone at The History Press for commissioning the book that you now hold in your hands.

A collection of this nature would not have been possible without some incredible photography, and all of the photographers have been individually credited throughout.

Several people suggested landmarks that I might have overlooked otherwise. Those whose favourites have been included are: Jason Evans, Laura Grove, Rory Castle Jones and Chris Peregrine.

Finally, in no particular order, my thanks go to: Emma Hardy and Bolly the cat; Kev Johns; Chris Carra; Owen Staton; Tim Batcup and all at Cover to Cover bookshop; Mal Pope; Wyn Thomas; Simon Davies and all at The Comix Shoppe; Ian Parsons; Peter Richards and all at Fluellen Theatre Company; Adrian White; and to my football-watching companions, Jean and Lindsay.

INTRODUCTION

When I first began to write a ‘little book’ of Wales’s greatest landmarks, it seemed like the easiest job in the world. I mean, anyone who lives in Cymru will know that all you have to do to find a landmark is walk out out of your front door, and there they are. Look up or down, left or right, and you’ll see towering mountains, glistening rivers, miraculous churches and prehistoric monuments strecthing for as far as the eye can see.

But therein lies the problem.

I discovered very early on that there are so many potential landmarks in God’s own country that whittling down the thousands on offer to just a measly few hundred would be a monumental task.

If I had included every landmark on my original longlist, this book would more resemble an encyclopaedia – and I’d still be writing it right now.

To put things into perspective, there are said to be around 600 castles in Wales alone, with around 100 of them still standing. That means I could have written about nothing but castles and still only covered around 50 per cent of them before hitting my word count.

The only way to put some kind of order on things was to decide upon a selection process. To begin with, I ticked off all of the ‘big hitters’ which are covered in the first two chapters – the world-class wonders that have, quite rightly, been declared UNESCO World Heritage Sites and Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

But with the likes of Snowdonia (Eryri), the Gower Peninsula and the Brecon Beacons (Bannau Brycheiniog) done and dusted, what next? It was important to include a wide selection of landmarks from all across Wales, and in order to strike a balance, I divided this book into eleven roughly equal-sized chapters, ranging from stately homes to neolithic megaliths.

Next, each of the places included had to have a uniqueness about them to elevate them above the crowd. This could be something simple, like an amazing view or an idyllic beauty spot, to something a bit more complex, like a convoluted history intertwined with wars, myths and legends.

This process worked well, but it did present me with one unique problem – many of the landmarks could quite easily have been included in multiple chapters. For example, eagle-eyed readers might notice that the beaches of Gower are strangely absent from the chapter about coastal landmarks; rather, they appear in the earlier chapter about Wales’s Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Or that The Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd are nowhere to be seen in the castles chapter; they can instead be found in the UNESCO World Heritage Sites section. While this isn’t ideal, the only alternative would have been to repeat information which, in a volume of this size, would have been something of a luxury.

Ultimately, this book does not claim or pretend to be a comprehensive guide to every landmark in Wales. Rather, it is intended to serve as a tantalising teaser to the treasures on offer, and one which will whet your appetite enough to inspire you to head off on a cultural adventure of your own.

I hope that you enjoy reading this collection as much as I enjoyed writing it, and even if some of the locations are already familiar to you, maybe you’ll learn something new and pick up some bits of trivia along the way.

If you are lucky enough to live in Wales, or are planning on visiting in the future, you can be certain of one thing: there are thousands of landmarks out there to explore, and many of them will be right on your doorstep.

Mark Rees, 2018

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

Most of the landmarks in this book are now commonly known by either their Welsh or English names. In some cases they might be known by both, or maybe an Anglicisation of the original Welsh name. I have used the most common place names and spelling throughout, and supplied Welsh and English translations where appropriate.

1

AREAS OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY

In 1956, the Gower Peninsula became the United Kingdom’s first Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Singled out for special conservation, it has since been joined by four others in Wales: Anglesey, the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley, the Llŷn Peninsula, and the Wye Valley, which partially crosses over the border into England.

Each beauty spot is unique; they were selected for a multitude of reasons, including the importance of their landscape, their ancient history, the surrounding area’s culture and heritage, their ecology and prominence of rare plants and animals, and in all five cases, their sheer good looks.

AONBs in Wales are designated by the Welsh government body Natural Resources Wales, which was formed in 2013 following the merger of the Countryside Council for Wales, Environment Agency Wales, and the Forestry Commission Wales. The areas are all protected by law, and the aim is to enhance, as well as preserve, their features.

These mountains and valleys, islands and lakes, cover about 5 per cent of the land. And as well as representing some of the best that the country has to offer, they are also filled with even more landmarks within landmarks.

South Stack Lighthouse. © Denis Egan (Wikimedia, CC BY 2.0)

ANGLESEY

Anglesey – Ynys Môn in Welsh – received its AONB status in 1967.

Sitting just off the north-west of the country, it is Wales’s largest island, covering 276 square miles of land. This makes it the largest island in the Irish Sea in terms of area, and second only to the Isle of Man in terms of population.

Its designated AONB area covers the vast majority of its coastline, approximately one third of the island. Its protected status not only preserves its existing treasures, but ensures that it won’t be damaged by any unsuitable developments in the future.

Anglesey is accessible from the mainland by two bridges: the Menai Suspension Bridge and the Britannia Bridge, which are landmarks in their own right and feature later in this book. The location makes it a popular destination for sailors, surfers and anglers, and the best way to explore it is along the 125-mile Isle of Anglesey Coastal Path. Starting at St Cybi’s Grade I listed medieval church in Holyhead, the county’s largest town, the route takes in its many beaches, which are backed by sand dunes and limestone cliffs.

When it comes to wildlife, there are many rare and threatened species on and around the island. Harbour porpoises can be seen in the water, the distinctive wings of the marsh fritillary butterflies in the air, while the rivers have seen the return of the otter.

The South Stack Cliffs, a Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) nature reserve, is home to up to 9,000 birds, including puffins and choughs. The rare South Stack fleawort plant is also endemic to the cliffs, but tread carefully – it is also home to an adder or two.

Inland, the Dingle Nature Reserve in Llangefni is 25 acres of ancient woodland divided in two by the Afon Cefni river. There are sculptures to be found along the wooden boardwalk, and its Welsh name, Nant y Pandy, is derived from an old wool mill that once stood in the valley.

Wales is home to the UK’s second-largest region of marshy fen area, which spans four nature reserves, three of which are in Anglesey. Collectively known as the Anglesey Fens, they are Cors Bodeilio, Cors Goch, and the largest of the trio, Cors Erddreiniog. The fourth, Cors Geirch, can be found in fellow AONB the Llŷn Peninsula.

There are three designated heritage coasts in Anglesey. Much like being designated an AONB, they are singled out for their importance by Natural Resources Wales for the benefit of the public who are free to explore and enjoy them.

North Anglesey is the island’s longest heritage coast, a 17-mile stretch of beaches that begins at Church Bay, a pebble and sand beach dotted with rockpools, and heads east towards Dulas Bay, a small beach with an eye-catching shipwreck.

Highlights along the route include Cemlyn Bay and Lagoon, which hosts an important colony of tern seabirds, and Amlwch, Wales’s most northerly town. Nearby Parys Mountain was home to Europe’s largest copper mine in the eighteenth century.

On the island’s south-west coast, the Aberffraw Bay heritage coast is a 4.5-mile trek around the giant sand dunes of Aberffraw Bay, some of which can reach as high as 10m. The walk starts in Aberffraw, which, in the Middle Ages, was the capital of the Kingdom of Gwynedd.

A spectacular landmark nearby is the Grade II* listed church of Saint Cwyfan, which is quite appropriately known as the ‘Church in the Sea’. Originally dating from the twelfth century, it stands on Cribinau, a tiny island cut off from the mainland following centuries of erosion, and is still used as a place of worship today in the summer months.

Other highlights include the fly-fishers’ favourite Llyn Coron, and the neolithic burial chamber Barclodiad y Gawres, between Aberffraw and the village of Rhosneigr.

Finally, Anglesey’s third heritage coast is an 8-mile route around Holy Island. It starts at Trearddur Bay, a popular bathing spot, taking in the must-visit South Stack as it winds its way towards the striking North Stack. There are numerous landmarks en route, from the island’s iconic lighthouse to its wealth of ancient stones.

Holy Island is home to Holyhead Mountain, which slopes down into the Irish Sea and hosts a large number of breeding birds. With an elevation of 220m, it is the highest mountain in the county. The highest mountain on the island of Anglesey, and the county’s second-highest mountain, is Mynydd Bodafon, with an elevation of 178m.

On a good day, the Emerald Isle can be seen across the waters from the peak of Holyhead Mountain, and the main route to Dublin by sea is from the port of Holyhead. The harbour’s Victorian breakwater at Soldier’s Point is the longest of its kind in the UK. Snaking its way 1.7 miles out to sea, you can wind your way along its promenade to reach the Holyhead Breakwater Lighthouse.

Did You Know …

Llanbadrig, the name of a village at the northern peak of Anglesey, translates as ‘the Church of St Patrick’. A church bearing the saint’s name can be found near the village of Cemaes, and, according to the legend, the Irish saint was shipwrecked there in AD 440 as he attempted to cross the waters. Seeking refuge in Ogof Badrig (Patrick’s Cave), he established a wooden church nearby, on the site of which the current church was built in the fourteenth century.

CLWYDIAN RANGE AND DEE VALLEY

The Clwydian Range and Dee Valley is the most recent addition to Wales’s list of AONBs.

Eglywseg Mountain. © Mattcymru2 (Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Designated in 1985, the heather-clad ‘gateway to north Wales’ covers miles of tranquil open land and forestry, tracing the route of the River Dee from the seaside town of Prestatyn to the hills of Llangollen.

The boundaries of the AONB were greatly expanded in 2011, heading southwards to take in the Dee Valley. It now covers 150 square miles of land, and newer additions include the castles Castell Dinas Brân and Chirk Castle, the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct World Heritage Site, and Valle Crucis Abbey. From its summits, you can enjoy views extending from the rugged peaks of north-west Wales to the Peak District National Park in central England. The AONB’s highest point is Moel y Gamelin hill, a Marilyn north of Llangollen, which stands 577m tall.

At the top of Moel Famau (554m), which straddles the border between the counties of Denbighshire and Flintshire, is the Jubilee Tower. This unfinished obelisk was started in 1810 to mark the golden jubilee of George III, but much of it was destroyed by strong winds in 1862.

The history of the area can be traced back 400 million years, with ancient finds scattered across the landscape. Foel Fenlli hill, which has an elevation of 511m, has an Iron Age hill fort at its peak, as does fellow Marilyn Penycloddiau. One of the largest in the country, it covers 64 acres, and a burial mound and stone tools are among the Bronze Age discoveries that have been made there.

There are also many legends associated with the area and strong links with Arthurian mythology. The Maen Huail in the Denbighshire town of Ruthin is a limestone block with a plaque which reads: ‘On this stone the legendary King Arthur beheaded Huail, brother of Gildas the historian, his rival in love and war.’ In the Mold village of Loggerheads, Carreg Carn March Arthur (The Stone of Arthur’s Steed) is said to bear the hoofprint of the legendary king’s mare Llamrai. According to the story, it was created as they jumped from a cliff while fleeing from the Saxons. It is now protected by an arched boundary stone bearing a plaque.

Rocks bearing names such as Craig Arthur (Arthur’s Rock) and Craig y Forwyn (Maiden’s Crag) can be found in the Eglwyseg Valley, home to a 4.5 mile limestone escarpment which is popular with rock climbers. With a high point of 513m at Mynydd Eglwyseg, the World’s End vale at the head of the valley offers panoramic views across the land.

The Horseshoe Pass mountain pass is a scenic route around the valley, which also leads to a unique landmark at its summit: the only cafe to be included in this book. The Ponderosa Cafe Complex is a remote place of sustenance, and an almost compulsory stop or meeting place for many people exploring the range.

Did You Know …

You can follow the Offa’s Dyke National Trail, which leads along the Welsh and English border, all the way from one AONB in the north of Wales, the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley, to another in the south of Wales, the Wye Valley?

LLŶN PENINSULA

The Llŷn Peninsula is Wales’s second-oldest AONB. Created in 1956, soon after the Gower Peninsula became the first in the UK, it spans around 62 square miles, covering about a quarter of the Gwynedd peninsula.

White Hall (centre) on Porthdinllaen Beach. © PangolinOne (Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Surrounded on either side by the Irish Sea and Cardigan Bay, with the ancient holy isle of Bardsey Island at its peak, the AONB takes in most of the area’s coast and hills. It is divided into two sections, north and south. The southern part begins at the small offshore island of Carreg y Defaid, curves around the coast before moving inland, and continues northward past the town of Nefyn following a break near Morfa Nefyn.

It is in the north where the peninsula’s highest peaks can be found, with the likes of Bwlch Mawr and Gyrn Ddu rising more than 500m. The tallest of them all is the three-peaked Yr Eifl, and its central summit, Garn Ganol, reaches 561m.

One of the best ways to explore the peninsula is by following the Llŷn Coastal Path, a 91-mile waymarked route which has been integrated into the Wales Coast Path. It starts at Caernarfon and passes many a landmark, as well as a few traditional kissing gates, as it leads the way to Porthmadog.

The beaches, such as seaside resort Abersoch, are very much classical golden sweeps of bay. A go-to destination for watersports aficionados, the peninsula was home to Wakestock for several years, said to be ‘Europe’s largest wakeboarding festival’.

There are several National Trust attractions in the peninsula, such as Llanbedrog, with its distinctive and brightly coloured beach huts. A more secluded gem is Porthdinllaen, a small fishing village within touching distance of the water.

When it comes to wildlife, grey seals and bottlenose dolphins can be seen off the coast, and there are many breeding spots for birds, such as the cove of Porth Meudwy, which is also a departure point to see countless more on Bardsey Island.

Pen Llŷn a’r Sarnau in Cardigan Bay is a huge protected Special Area of Conservation (SAC), and is home to many marine habitats, plants, animals and shallow reefs. Extending down towards Aberystwyth, the first half of its name, Pen Llŷn, refers to the Llŷn Peninsula, while the second half, Sarnau, is the Welsh word for causeway, relating to a trio of reefs.

Another SAC and Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) is Cors Geirch National Nature Reserve. In the spring, the marshy wetland between Nefyn and Pwllheli is awash with colour, coming alive with primroses and bluebells that attract winged insects such as the marsh fritillary butterfly, which can also be seen in Anglesey.

Did You Know …

Porthor, a secluded beach on the Llŷn Peninsula, is known as the ‘whistling sands’. It is one of the few beaches in the world were the sands do actually ‘whistle’, with the sound created when the grains rub together.

GOWER PENINSULA

The Gower Peninsula is the UK’s original AONB, and it’s easy to see why. Singled out for its natural beauty in 1956, the peninsula just west of Swansea is 70 square miles of golden sands, archaeological wonders, protected geology and countless curiosities, all of which can be explored along the 38-mile Wales Coast Path that circles from Mumbles to Crofty.

Gower, or Gŵyr in Welsh, is probably best known globally for its beaches, and arguably the most famous of them all is Rhossili Bay. The largest beach on the peninsula, its 3 miles of white sand has claimed many an award over the years, including ‘Best Beach in Europe’ from Suitcase magazine. It even ruffled a few feathers in the southern hemisphere when the magazine also named it as the ninth best beach in the world – edging out some of the more celebrated beaches Down Under in the process.

Rhossilli Worm’s Head. © tomyst (Wikimedia, CC BY 3.0)

Its most distinctive, and photographed, landmark is Worm’s Head, named by the Vikings for its resemblance to a dragon’s head, with wyrm being the Old English word for dragon. The rocky tidal island protrudes into the sea and is connected to the mainland by a causeway. It can be crossed along the ominously named Devil’s Bridge, a naturally formed bridge that leads towards the ‘serpent’s’ head.

There are twenty-five beaches along the coastline in total, and many others are also award winners, and regularly receive Blue Flag awards, the gold standard for high-quality beaches. While a detailed look at every beach in Gower is beyond the scope of this book, they include Oxwich Bay, Gower’s second-largest beach and a National Nature Reserve; the National Trust-owned Whiteford, with the vast Whiteford Sands; Port Eynon, which has a fascinating history of smugglers lurking in its caves, as do the more secluded areas like Brandy Cove and Pwll Du; Caswell Bay and Langland Bay, which are both surfing hotspots and popular tourist destinations, with the latter housing a long row of in-demand and well-known beach huts; and from a purely aesthetic point of view, the bay with the most picturesque panorama would probably be Three Cliffs Bay, a dramatic coastal landscape bordered by Pobbles Bay and Tor Bay.

Inland, the Gower offers cliffs, farmland, and more than eighty ancient scheduled monuments, many steeped in myths, legends and ghost stories. On the 5-mile-long Cefn Bryn ridge is the neolithic burial ground Maen Ceti (Arthur’s Stone). According to one variation of its origin, King Arthur himself was walking along the Carmarthenshire shore when he felt a pebble in his shoe. Removing it and hurling it across the estuary, it grew in size as it landed in its current spot opposite Reynoldston car park.

Another ancient landmark which is worth the extra effort to see, if not necessarily enter, is Paviland Cave. In the nineteenth century, an archaeological find of global significance was discovered by William Buckland, Professor of Geology at Oxford University, just inside the cave’s entrance. Named ‘The Red Lady of Paviland’, it was a skeleton covered in red ochre which had stained the bones, and which was mistakenly believed to be female, but was later confirmed to be male. Access to the cave, which is just 10m high and 7m wide, can be perilous and is often blocked by the tide.

Did You Know...

The Gower Peninsula is where the much-decorated composer Sir Karl Jenkins was born and raised. The first Welsh composer to receive a knighthood hails from the village of Penclawdd, which is also famous for its cockles.

WYE VALLEY

The Wye Valley, or Dyffryn Gwy in Welsh, has quite a claim to fame: it is credited with giving birth to British tourism in the eighteenth century. Tourists have flocked to its wild woodlands, limestone gorge and untamed waters for centuries, with some of the Romantic wanderers who paid a visit to draw inspiration for their words and works of art including Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Gilpin, Thomas Gray, Alexander Pope, William Makepeace Thackeray, J.M.W. Turner and William Wordsworth.

View from Devil’s Pulpit to Tintern Abbey. © Nessy-Pic (Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The only AONB to extend across both Wales and England, the Wye Valley was designated in 1971, and its 128 square miles contain SSSIs, SACs, Scheduled Monuments and National Nature Reserves.

Flowing through the valley is the River Wye, the first complete river to be named an SSSI in Britain. At 134-miles long it the fifth longest river in the UK, and runs along the border of England from Plynlimon, the Cambrian Mountains’ highest point, down to the Severn Estuary. It criss-crosses the English counties of Gloucestershire and Herefordshire along the way, before winding back into Wales to its mouth in the Monmouthshire town of Chepstow.

As well as being the Wye Valley’s centrepiece, the river also serves as a good route to follow when exploring some of the AONB’s many landmarks. There are launch points for canoeists and kayakers along the way, and the riverside can be followed on horseback, or by climbing the rocks of the limestone gorge.

The Wye Valley Walk is a 136-mile trek which takes around twelve days to complete. Broken down into eight more manageable walks, the longest starts at Chepstow Castle overlooking the Wye.

The woods that line the riverbanks are of international importance and can be seen on the first part of the walk from Chepstow to Monmouth, a 17-mile journey through sometimes dense forestry along the lower Wye gorge. The gorge’s widest point is approximately 2 miles across at Welsh Bicknor, which, despite the name, is actually in England, just south of the village of Goodrich in Herefordshire. After reaching Monmouth, the Wye Valley Walk heads northwards with routes to Ross-on-Wye, Hereford, Hay-on-Wye, Builth Wells and Rhayader before ending at Plynlimon.

Stand-out landmarks are the Gothic splendour of Tintern Abbey and Monmouth Castle, the birthplace of Henry V. A less obvious landmark, but one which offers panoramic views across the land, is Beacon Hill on Trellech Plateau near the village of Trellech. The heavily wooded area is full of wildlife, and if you keep your eyes and ears open as night falls in the summer you might hear the rare nocturnal nightjar bird.

Other rare species can be found at Croes Robert Wood nature reserve, an SSSI owned by Gwent Wildlife Trust. It is home to the endangered dormouse, along with rare trees, birds, butterflies and moths. For a glimpse back in time, Pentwyn Farm’s flowers and hay meadows have remained as they would have looked hundreds of years ago, while its farm barn has been restored as accurately as possible.

Did You Know …

When the Wye Valley inspired William Wordsworth to write ‘Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey’ in 1798, he claimed that the entire poem formed in his head while walking, before he even had time to sit down and put ink to paper.

2

WONDERS OF THE WORLD

When it comes to landmarks, they don’t come much more spectacular than those selected by UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

In its mission statement, UNESCO says that it aims to help countries protect their ‘natural and cultural heritage’, and some of the more famous places from around the world that have been chosen for safe keeping include the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, the ‘floating city’ of Venice in Italy, the Grand Canyon in America, and the Taj Mahal in India.

In Wales, four UNESCO World Heritage Sites stand proudly among the best in the world: Blaenavon Industrial Landscape, Pontcysyllte Aqueduct and Canal, The Castles and Town Walls of King Edward in Gwynedd, and The Slate Landscape of Northwest Wales.

BLAENAVON INDUSTRIAL LANDSCAPE

The scarred industrial landscape surrounding the town of Blaenavon, which is spelled Blaenafon in Welsh, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000. Said to be the best of its kind in the UK, the area, which covers 13 square miles, records a period in Welsh history when the Industrial Revolution forever changed the face of the country and the lives of those living through such turbulent times.

By the nineteenth century, Blaenavon led the way in coal and iron production. Tightly knit communities sprang up around the works, and their way of life up to 1914 has now been preserved for future generations.

View of the National Coal Museum. © Nessy-Pic (Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In 1984, Blaenavon’s town centre was awarded conservation status, which means that much of it has retained the charm of earlier centuries, from the well-preserved terraced houses to its cobbled streets. The town also produces its own food and drink, available for sampling in a traditional setting.

A natural starting point when exploring Blaenavon is the Blaenavon World Heritage Centre. Housed in what was St Peter’s church school, it was built in 1816 by Sarah Hopkins, the sister of ironworks’ manager Samuel Hopkins, to provide free learning to the children of the workers. It continues in an educational capacity today, with a replica of a Victorian classroom.