18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

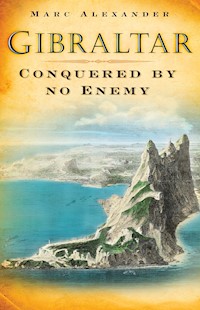

A history of Gibraltar.

Das E-Book Gibraltar wird angeboten von The History Press und wurde mit folgenden Begriffen kategorisiert:

gibraltar,history of gibraltar,british military history,chronicle,british overseas territory

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

For Olivia

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to express his gratitude to the following for encouragement and practical assistance in the preparation of this book:

Paul Abrahams, Mark Baker, Sophie Bradshaw, Fiona Dallas, Olivia Davies, José Guerrero, Peter Halbert, Jennifer Hassell, Joanna Howe, Sharon Jenner and David Pinder.

The Alexandra Park Library, London, The British Library, The Gibraltar Chronicle, the Gibraltar Museum, the Gibraltar Office, London, the Imperial War Museum and Luis Photos, Gibraltar.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1The Pillars of Hercules

2The Moors’ Gateway

3A Chapter of Sieges

4The ‘Catholic Kings’

5‘Most Loyal’

6Habsburg or Bourbon?

7Rooke Takes the Rock

8Enemies Within and Without

9The Treaty of Utrecht

10Pawn rather than Castle

11Alliances, Treaties and Secrets

12‘Imperious Cupidity’

13‘Britons Strike Home!’

14A Glorious Occasion

15The Junk Ships

16The Grand Attack

17‘We are all friends now’

18Peace and War

19Peace without Pride

20A Right Royal Governor

21Trafalgar

22Friends and Foes

23Crown Colony

24The Great Mystery

25‘Utterly Profitless’

26Changing Times

27The Panther’s Leap

28War and Peace

29Sanctuary on the Rock

30Preparations for War

31Bombs and Spies

32The Felix Threat

33Operation Torch

34From Colony to City

35The New Gibraltar

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

All photographs by the author unless otherwise stated.

Introduction

‘As safe as the Rock of Gibraltar’ is an expression understood in many areas of the world. Its meaning reflects both the appearance and the history of the Rock.

In prehistoric times its caverns sheltered Neolithic men and women, just as its natural defences sheltered its people from assault by their enemies in more modern times. For the last three centuries it has remained British despite siege, famine and fever. Thanks to the fortitude of its garrison and civil population in facing hardship and repelling attack it became a patriotic symbol, in latter days being dubbed ‘the Last Rock of Empire’. It is no longer part of an empire but links with Britain remain and what was once the world’s most famous fortress has evolved into a democratic community.

Officially designated a British Overseas Territory of the United Kingdom, Gibraltar is situated at the southern tip of Spain, overlooking the Strait named after it, which is the strategic gateway to the Mediterranean. Its area of 2½ square miles is inhabited by nearly 30,000 people. The population is truly multi-racial, its forebears coming from Britain, Genoa, India, Italy, Malta, Minorca, Morocco, Portugal, Sardinia and Spain. Yet if a person living on the Rock is asked about his or her nationality, the answer is most likely to be ‘I am Gibraltarian.’

While English is Gibraltar’s official language, most Gibraltarians speak Spanish as well. There is also a local patois known as Llanito, a blend of English and Spanish Andalusian together with words that echo from the Rock’s cosmopolitan past. The majority of Gibraltarians are Roman Catholics but a wide variety of other Christian and non-Christian faiths flourish. Apart from his local Church of England duties, the Bishop of Gibraltar is in charge of the Anglican Diocese of Europe.

One of the misconceptions about Gibraltar is that the British seized the Rock in 1704 in the name of Queen Anne for their own advantage. Anglo-Dutch troops did capture the Rock but it was during the War of the Spanish Succession and the action was carried out on behalf of the Austrian Archduke Charles, the Habsburg claimant to the throne. When the war ended with the Treaty of Utrecht and various European territories were reallocated, it was agreed that Britain should take over Gibraltar ‘with all manner of right for ever …’. What is not generally known is that there were times when the British government was eager to relinquish it.

Spain’s attempts to secure the return of the Rock to Spain have been an enduring matter of contention, at one point provoking the most famous siege in history after that of Troy. Sympathisers with the Spanish objective ask how would the people of Britain feel if three centuries ago a Spanish force invaded Portland Bill and the flag of Spain flew over it ever since. In reality the ‘Gibraltar question’ is far more complex as the following pages will show.

Gibraltar’s head of state is Queen Elizabeth II who is represented on the Rock by the Governor. Since Gibraltar won internal independence and has it own parliament, he no longer controls the administration of the city but remains responsible for defence, foreign relations and security. The Gibraltar Parliament, which convenes at the House of Assembly, has fifteen elected members and the equivalent of prime minister is referred to as the Chief Minister.

To explore Gibraltar is to take a walk through history, from the museum housed in Europe’s best preserved Moorish Baths to the Rock’s tunnels, which were one of the most notable feats of engineering in the Second World War. In the Trafalgar Cemetery lie men who died in the battle of that name and mounted at the Napier Battery is preserved the famous 100-ton gun, which had a range of 8 miles for its 2,000lb shells. Sites with more peaceful connotations include the Rock’s natural caverns, the most famous being St Michael’s Cave where ballet and musical events are produced in awesome surroundings. No reference to the traditional side of the Rock would be complete without mention of the famous apes, although they are not apes at all but tail-less monkeys known as Barbary Macaques, which are unique in Europe. According to legend the British will no longer hold the Rock if the apes die out but the fable is unlikely to be put to the test as there are between 200 and 300 of these mischievous creatures on the Upper Rock.

Among the attractions that help Gibraltar’s tourism industry is its wildlife, especially the mass migrations of various bird species from the Rock to Africa, which entice bird-watchers from near and far.

For the visitor Gibraltar retains its reputation of being a free port. Although it became a member of the European Union by virtue of the British Treaty of Accession in 1973, Gibraltar remains outside the Customs Union. This means that visitors from EU countries still have the advantage of purchasing duty-free goods, which is not permitted in the rest of the European Union.

Gibraltar has found its own voice and prospered yet the question of sovereignty remains unresolved. Spain wishes to regain this tiny but highly significant scrap of land against the wishes of the Gibraltarians whose ‘democratically expressed wishes’ are guaranteed by the British government. It remains an on-going stalemate.

It has been the aim of the author to present a factual history of the Rock without bias. As someone who has respect – and affection – for both the Rock and Spain, he was pleased that he was able to write in the final chapter how everyday co-operation between the Rock and its neighbour has recently progressed to the advantage of those on both sides of the frontier. May it continue.

1

The Pillars of Hercules

Mythological fable tells that the tenth labour of Hercules was to capture oxen belonging to the three-headed monster Geryones. After succeeding the task he arrived at the frontiers of Africa and Europe where he commemorated his feat by raising an immense monument at either end of the isthmus that joined the two continents. In the course of this he created an enormous trench through the land bridge, which allowed the Atlantic Ocean to flood a great valley to become the Mediterranean Sea. On the north shore of this channel, which we know as the Strait of Gibraltar, reared Mount Calpe, on the south Mount Abyla – as the Greeks and Romans called them – and these became famous as the Pillars of Hercules.

A theory linking the Rock with another legend from the realms of antiquity was investigated in 2003. Working on clues suggested in ancient writings, the Iberio-Marroqui Atlantic Expedition set out in search of a submerged island in the Atlantic side of the Strait of Gibraltar, which could have inspired the legendary story of Atlantis as described by Plato. Expedition divers seeking evidence of the lost land on the seabed were rewarded by the discovery of paving slabs, building blocks and other stone remains.

Myths often contain a glint of truth and it is a fact that Europe and Africa were once joined where the Strait of Gibraltar lies today. This is confirmed by fossilised bones of African animals, such as the rhinoceros and elephant, which have been discovered in some of Gibraltar’s caves, which number over 140.

The geological record shows that during the vast vistas of prehistory sea levels rose and fell exceedingly as ice ages were followed by global warmings when glaciers and polar ice melted. During one of these interglacial occurrences the sea level rose to such an extent that the isthmus linking the two continents was broached and, like the bursting of a dam, the water of the Atlantic cascaded into the lowland with its chain of lakes that lay between northern Africa and southern Europe. It gouged out a channel whose length east to west is 38 miles; its width varies between 15 and 25 miles and has an average depth of 1200ft. It is tempting to speculate as to whether it was some faint folk memory of this cataclysmic deluge that inspired ancient stories of the Flood such as is told in Chapter 7 of Genesis when ‘the waters prevailed exceedingly upon the earth …’. Alas for such imaginative speculation, the great period of world temperature change and interglacial ages was the Pleistocene Epoch, which commenced around 2 million years ago, and though hominids appeared in the latter part of that age it was not until c. 30,000 BC that modern man replaced earlier man-like forms.

It was in the Jurassic Age, the age of the great dinosaurs and which is reckoned at commencing 195 million years ago, that great layers of lime-stone began to form on the bed of the ocean, which then covered much of what Europe is today. As the earth cooled and shrank, sections of the surface were gradually ‘squeezed’ upwards to form mountain chains. Over an immense length of time, difficult for us human ‘newcomers’ to imagine, such an upthrust of limestone was sculpted by geological shifts and eroding weather into the Rock of Gibraltar.

At some time after the great inundation it is likely that Gibraltar was an island but it has long been joined to the Spanish mainland at La Linea by a short isthmus no more than 10ft above sea level, and which was transformed by the RAF into a runway that now serves the compact Gibraltar airport.

In 1856, there was a dramatic discovery of fossilised man-like remains near Düsseldorf in the Neanderthal ravine, which caused a wave of scientific excitement around the world. It was said to be the world’s oldest man-like relic, which gave the name Neanderthal Man to a race that had lived in Pleistocene Europe. Eight years earlier a woman’s skull of similar antiquity was found in Forbes’ Quarry at the base of the northern face of the Rock. It was kept in a cupboard after the Gibraltar Scientific Society had conferred over it without realising its importance. Had it been recognised for what it was we would now be referring to ‘Gibraltar Woman’ rather than Neanderthal Man. Today the skull is to be seen in the Gibraltar Museum.

The evidence that Gibraltar had inhabitants over 100,000 years ago was supported in 1928 when the damaged skull of a Neanderthal child was found at the Devil’s Tower, an old lookout tower on the isthmus that was demolished during the Second World War.

The first named dwellers of the area were the Tartessians whose ancestry went back to the Bronze Age. Then, nearly 3,000 years ago, the seafaring Phoenicians established a port they named Carteia where an oil refinery stands today at Algeciras. Protected from the eastern Levanter wind by the Rock, it was a safe haven for ships in what is now called the Bay of Gibraltar – or Algeciras Bay, depending upon your viewpoint.

In those days the Pillars of Hercules marked the end of the known world – the Non Plus Ultra. Beyond them was the River of Ocean, as the Atlantic was then called. Unimaginable terrors lurked in those uncharted waters and once out of sight of land a vessel might sail over the edge of the world. Mons Calpe itself was a place to beware of as it was believed that here, in its western rock face, was the entrance to the Kingdom of Hades, the underworld Realm of the Dead. It is thought that this sinister entrance was the spectacular St Michael’s Cave, which today is one of Gibraltar’s main tourist attractions.

If to sail out beyond The Pillars of Hercules was to court disaster, one wonders why the Phoenicians established Carteia so close to them. The answer was that these daring traders did risk sailing beyond them to follow the Spanish coastline north and on as far as the island of Britain in quest of what was the most valuable commodity of the age – tin. Then the metal used for weapons and armour was bronze, an alloy of copper and a small amount – usually around 4 per cent – of tin. There was no shortage of copper but tin was a different matter. Understandably the Phoenicians wished to keep the lucrative trade to themselves and no doubt exaggerated the terrors real and imaginary of the River of Ocean to deter competitors.

The first man recorded as sailing out through the Strait of Gibraltar was one Kaleus who braved going into the unknown in the seventh century BC. The Pillars of Hercules became part of history after the remarkable Necho II became the Pharaoh of Egypt. Apart from attempting to construct a canal to link the Nile to the Red Sea, he was responsible for one of the earliest voyages of discovery. In the fifth century BC the Greek historian Herodotus wrote:

The Egyptian king sent out a fleet manned by a Phoenician crew with orders to sail round Libya (Africa) and return to Egypt and the Mediterranean by way of the Pillars of Hercules.

The Phoenicians sailed from the Red Sea into the southern ocean, and every autumn put in where they were on the Libyan coast, sowed a patch of ground, and waited for the next year’s harvest. Then having reaped their grain, they put to sea again, and after two full years rounded the Pillars of Hercules in the course of the third, and returned to Egypt. These men made a statement which I do not myself believe, though others may, to the effect that as they sailed on a westerly course round the southern end of Libya, they had the sun on their right, to the northward.

In later centuries their statement on the changing position of the sun was proof that they had actually sailed in the southern hemisphere.

One can imagine the elation of the Phoenician sailors as the Rock of Gibraltar appeared on their horizon and that thanks to their courage and endurance ‘Libya was first discovered to be surrounded by sea,’ as Herodotus said.

In the course of time other people settled in the lands surrounding Gibraltar. Phoenician influence in the western Mediterranean waned when Tyre, the seaport city of Phoenicia (now Lebanon) and the great market place of the Mediterranean, endured a thirteen-year siege by Nebuchadrezzar II of Babylon. Carteia became a Carthaginian city and allied Greeks settled there. When the struggle between the two Mediterranean superpowers – Rome and Carthage – ended with the destruction of Carthage by Scipio in 146 BC, Carteia and the surrounding region came under Roman domination. It was to remain a Roman colony for nearly six centuries.

Other towns were established that have survived to the present times such as Portus Albus, situated on the west shore of the Bay of Gibraltar, and which is known today as Algeciras. Across the Strait Saepta Julia (now Ceuta) and Tingis (Tangier) were established. Twenty miles west-ward along the coast from Gibraltar Julia Traducta was built on the most southernmost tip of Spain and in due course became known as Tarifa. Later, when the Moors held Tarifa they levied fees on vessels entering the Mediterranean at that point, from which comes the word ‘tariff’.

Although there were settlements and towns in the Gibraltar region, the Rock itself was then regarded as too inhospitable for habitation or fortification.

The beginning of the fifth century saw the decline of the Roman Empire with the legions in Britain being withdrawn to protect Rome against the threat of Alaric’s Visigoths. At the same time Vandal hordes crossed the Pyrenees and moved west, sacking Carteia in 409 AD and establishing themselves in what they called Vandalucia – Andalucia today. They did not remain long for they were looking across the Strait to the rich Roman province of Mauritania, which covered what is Morocco and Algeria today. Nineteen years after the fall of Carteia the Vandal king Gaiseric led his subjects – one account gives their number as 80,000 – out of Vandalucia to invade Mauritania and within a decade establish an empire stretching across North Africa. The Vandals’ place in Spain was taken by the Visigoths whose Arian Christianity differed from Roman Christianity with the doctrine that Christ was not equal to God the Father.

The Christian Visigoth kingdom was to last for three centuries but it had an inherent weakness due to the fact that its kings did not inherit the throne through primogeniture but were elected. This resulted in political disunity, which ultimately weakened its defences against the next wave of invaders.

Around 625 the Prophet Muhammad began to dictate the Koran and such was the unifying effect of the new religion upon the Arabs they began what H.G. Wells described as ‘the most amazing story of conquest in the whole history of our race.’ Within eight decades the warriors of Islam, fervent to spread the new faith, had won an empire larger than that of Rome, stretching east to the borders of China and west to the Pillars of Hercules, which they reached in 681. Here they failed in an attempt to capture Saepta Julia (Ceuta), which was governed by the Christian Count Julian who was allied to Visigoth Spain through his marriage to the daughter of King Witiza. By-passing Saepta Julia, the Arabs and Berbers who they had converted to the new faith, and were collectively referred to as Moors by the Christians, took Tingis (Tangier), which they garrisoned with 10,000 troops.

A widely told version of events that led to the Arab invasion of Spain is that Count Julian’s beautiful daughter Florinda became a maid of honour to Queen Egilona at the court of King Roderick, who succeeded King Witiza after his death in 710. It was said that seeing her in a palace garden one evening, Roderick became so passionately attracted by her beauty that when he was alone with her he ‘violated the chastity of that lovely virgin’. When Count Julian learned of the rape he determined to avenge his daughter’s dishonour. There was also another reason for the Count’s anger against the King. Following the death of Witiza his eldest son Aquila had his hopes of succeeding his father dashed when the nobles elected Roderick to the throne. This led to a civil war between those who supported Aquila and those loyal to the new king who soon routed the rebels.

In desperation Aquila appealed to his brother-in-law Count Julian for support. With Saepta Julia in constant danger of attack by Moors in the surrounding territory, the Count was not in a position to become involved in a civil war but he devised a plan to overthrow his enemy. He made contact with Musa ibn Nasayr, the brilliant Arab general who had planted the banners of Islam across North Africa, and suggested that with his help the Moors could cross the Strait. There they would find support among those loyal to the memory of King Witiza and those whose dislike of Visigoth domination was greater than their fear of Islam. Musa agreed and obtained permission to make a reconnaissance raid across the Strait from his master the Caliph Al-Walid in Damascus.

Using ships provided by Count Julian, Musa sent a 500-strong force across the Strait in 710. It was led by one of his lieutenants, Tarif abu Zarah, who landed at Julia Traducta, which became known as Tarifa in his honour. After pillaging the area the raiders returned laden with loot, captives and stories of the wealth and fertility of the land they had ravaged. When this was supported by a further raid, the Caliph agreed to Musa mounting a full-scale invasion.

Commanded Tarik ibn Ziyad, an army of Arabs and Berbers, estimated by some historians at 12,000 fighting men, set sail from Tingis and, according to Arab historians, landed under the shadow of the Rock on 27 April 711. Following this, Mons Calpe – the name by which the Rock was known – was changed to Jebel el-Tarik (‘Mount Tarik’), which evolved into ‘Gibraltar’.

2

The Moors’ Gateway

It did not take long for Tarik to capture Algeciras from where he was to launch his campaign against the Visigoth king. In the July of 711 a decisive battle took place beside the Guadalete River that was said to have lasted nearly a week before Tarik was victorious. The defeat of King Roderick, reputed to have had great numerical superiority over Tarik’s army, was not entirely due to the invaders’ military skill but in some degree resulted from the discord that appears to have been customary among the Visigoths.

This was demonstrated by the defection to Count Julian by Don Oppas, the Archbishop of Seville, the brother of the late Witiza and uncle of the ravished Florinda, who was in command of a large number of Christian troops. The example of a Christian dignity aligning himself with invaders of a rival faith in order to see Roderick overthrown led to other significant defections and the triumph of Tarik. The fate of Roderick remained a mystery. Arab sources claim that Tarik slew him with a spear and sent his head to Musa. Some Christian legends tell that he was drowned while trying to cross the Guadalete, and others that he escaped and spent the remainder of his life in a monastery. Whatever his fate, it seems that the dishonoured Florinda was avenged.

Meanwhile the increasing ascendancy of the Crescent over the Cross was further secured when Tarik captured Cordoba and then the Visigoth capital of Toledo. Here Sephardim Jews, who had settled in Spain before the arrival of the Visigoths and who made up a large proportion of the population, opened the city gates to the conqueror preferring the authority of Islam to that of their previous Christian rulers.

Tarik not only ended the civil war in favour of the supporters of the Witiza family but opened the way for the Moors to occupy most of Spain for the next eight centuries.

In June 712, Musa entered Spain with a mostly Arab army of 18,000 men. He captured Seville and Mérida and after wintering at Toledo he and Tarik continued the advance of Islam across Visigoth Spain. It is said that with Tarik’s continuing success Musa became concerned that his lieutenant’s military reputation might eclipse his own. He therefore accused Tarik of exceeding his orders, claiming that he had been sent merely to spy out the region, not defeat the king of the Visigoths. For this act of disobedience he was humiliated with a whipping and imprisoned while Musa arrogated his fame and continued the conquest until the only surviving Christian states were in the Pyrenees and on the northern coast of Spain. Musa was now so confident of his position that he arranged for his son to marry King Roderick’s widow.

When the Caliph summoned him to Damascus he set out gladly in anticipation of a triumphal reception such as was accorded to victorious Roman generals. In order to play the role of the conquering hero he took with him several hundred noble captives, suitably chained, and cargoes of treasure looted from Spain. But instead of receiving honours he was given the decapitated head of his son, and instead of a life of ease he was reduced to beggary for the rest of his days. The Caliph had been enraged by Musa’s treatment of Tarik and a marriage between his son to the Visigoth queen suggested that the general aspired to a combined Moorish and Visigoth dynasty separate from the caliphate.

Yet despite his fall from favour Musa’s military achievements in North Africa passed into legend and the southern Pillar of Hercules, up to then Mons Abyla, became known as Jebel Musa.

Meanwhile the march of Islam continued across Al Andalus, as the Arabs called Spain, and on into central France until 732 when a Moorish army was decisively defeated by Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours.

Once the battles had been won there was little internal opposition to the new masters of Spain. Aristocratic Visigoth families who had supported Witiza and his sons retained extensive estates in return for the payment of tribute. Freed from the persecution they had suffered under Visigoth rule, the Jews welcomed the regime change, which also gave a degree of freedom to the serfs. Conversion to Islam became widespread and Spanish converts, known as muwallads, became a significant element in the Moorish communities. Those who remained unconverted had little to fear for remaining loyal to their traditional faith and, like the Jews, formed affluent groups in the Muslim-controlled cities.

The disunity that had been the bane of the Visigoths was inherited by their conquerors. In 740, a Berber revolt in Morocco was mirrored in rebellion and tribal feuding in Spain, and the next 200 years saw a number of such destructive conflicts.

In 755, the Omayyad prince Abd-al-Rahman survived a massacre of his royal relations in Syria and fled west across North Africa, earning the nickname of ‘the Wanderer’. His mother had been the Berber favourite in his father’s harem and in Morocco he found sanctuary with her tribe until a pro-Omayyad alliance urged him to cross the Strait of Gibraltar and become their leader. With his supporters he captured Cordoba and, breaking away from the domination of Damascus, he became Emir of al-Andalus and governed for the next three decades. Thus the Omayyad Dynasty began.

Throughout his reign Abd-al-Rahman strove to unify the disunited country. Under the Omayyads the country became prosperous and there was a flowering of Moorish culture exemplified in the building of the famed Great Mosque, ‘the glory of Cordoba’, which was said to surpass all the capital’s Moorish and Christian buildings. Yet during the Omayyads’ 173-year period there was often dissension and revolt so that by the eleventh century their power had lessened to the extent that there were ten independent states in Spain, Gibraltar becoming part of the Kingdom of Seville.

Coinciding with the twilight of the Omayyad era was the revitalisation of the Christian kingdoms in the north of the country – Aragon, Castile, Leon, Galicia and Navarre – with Aragon and Castile becoming foremost in the crusade to win back Spain – the Reconquista. While the contest was to continue until 1492, the same year that Columbus set out from Palos, it would be wrong to imagine that Christian overlords formed a wholehearted alliance to regain the mastery of Spain or that the Moors presented a united front against them. On the contrary, it was not unusual for Christian to fight rival Christian in civil war and for Moor to fight Moor, or for Christian and Moorish lords to forget their religious differences to form alliances in order to gain ascendancy over neighbours of either faith.

In the middle of the eleventh century a Berber military brotherhood, dedicated to a return of fundamental Islam, seized power in Morocco. Known in history as the Almoravids, they inspired unease in the Moors of southern Spain in case they should cross the Strait to enforce religious reformation with the sword. Although the Rock of Gibraltar overlooked the Moorish gateway into Spain, it had been considered to be too inhospitable for any form of settlement or stronghold. But in 1068, under the threat of the Almoravids, the governor of Algeciras was instructed ‘to build a fort on Jebel el-Tarik and to be on guard and watch events on the other side of the Strait.’

As events turned out the Almoravids did not need to invade Spain, they were invited. In 1085, the Spanish Moors were aghast when their foremost city Toledo fell to King Alfonso VI of Castile, which meant that his Reconquista army was now a threat to Moorish Seville and Cordoba. Setting aside their previous misgivings, the Moors appealed to Yusuf ibn Tashfin, the leader of the Moroccan Almoravids, to come to the aid of his brother Muslims. The Bay of Gibraltar was his point of entry and he marched north, enlarging his army with local Moors as he went. His target was Alfonso, who at that time was laying siege to Zaragosa. On learning of the approaching Almoravids’ army he left Zaragosa to confront this new enemy and the two sides met in Zallaka on 23 October.

Alfonso was defeated in the battle whose ferocity can be gauged by the number of Christian troops killed. According to Arab historians this was in the region of 24,000, their heads being piled up into towers by the victors. No doubt to the relief of the Spanish Moors, Yusuf returned to Morocco though he kept control of the area between Gibraltar and Algeciras. This he used as a bridgehead in 1090 when he returned with his army, won back much of the land that had been taken by King Alfonso, though not Toledo, and replaced the rule of the weakened Omayyads with that of the Almoravids.

This dynasty was destined to be short-lived due to circumstances similar to those that had brought it about. From the Atlas Mountains emerged a sect known as the Almohads whose vision of Islam was even more fundamental than that of the Almoravids. Inspired by religious fervour to cleanse the faith that they believed had deviated from the strictures of the Prophet, these zealots became the masters of Morocco by the middle of the twelfth century. They despised the Muslims across the Strait as unworthy followers of Islam and their reluctance to wage holy war against the Christian states. The fact was that the Almoravid dynasty was disintegrating just as that of the Omayyads had done.

History repeated itself when Alfonso VII of Castile, having taken advantage of the decline of the Almoravids, captured Cordoba, then the Moors’ capital, and attacked the emirates of Granada and Seville. In desperation the Moors again sought aid from North Africa and in 1146 an Almohads’ army began the third Islamic invasion of Spain. Within three years the territory and cities that had fallen to Alfonso had been won back, and the new Almohads’ dynasty established.

With Islamic Spain under their control, the Almohads concentrated on extending their rule across North Africa to Tunis under the leadership of the Emir Abdul al-Mumin. He was well aware of the strategic value of Gibraltar as the link between his two dominions. When he visited Spain in 1160 to hold court he named it Jebel-al-Fath, meaning ‘The Mount of Victory’. He then ordered the building of a fortress and a town on the Rock to be named Medina-al-Fath – the City of Victory. According to an Arab historian, Abdul ‘traced out the buildings with his own hands, and when, after remaining for some months there, and providing for the government of Al Andalus, he returned to his African dominions, appointing his son Abu Said, then Governor of Granada, to superintend the building …’.

The architect Ahman ibn Basu and the engineer Haji Ya’ysh were briefed that it should have a mosque, palaces and reservoirs with a defensive wall as befitted as the Almohads’ capital. Today hardly anything is known of their work though it is thought the site was likely to have been commenced where the later Moorish Castle now stands. Today its only possible relic is the remains of a time-eroded wall on the Upper Rock. Medina-al-Fath marked the beginning of Gibraltar’s role in history.

When Abdul died in 1163 his place was taken by his son Abu Ya’Kubibn. It was unlikely that he completed his father’s plan as he concentrated on making Seville his capital.

Despite bickering between the Christian kingdoms the Reconquista continued with victory and defeat on both sides. This was exemplified when Alfonso VIII of Castile made an audacious raid on Algeciras and Tarifa in 1194, then next year suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Alarcos. Fourteen years later Aragon, Castile, Leon and Navarre temporarily suspended their feuding to unite in the Christian cause and, led by Alfonso VIII, won the great battle of Navas de Tolsa that marked the beginning of the Almohads’ decline.

Yet again history was to repeat itself in the latter half of the thirteenth century with the fourth Moorish invasion of Spain. Across the Strait the Bini Merinids, another fundamentalist faction, came to power. Like their predecessors, they were intent on cleansing what they saw as a degenerate religion by force of arms. Fired by their religious militancy, they rebelled against the Almohads whom they overthrew when they captured Fez.

In 1275, Granada and Mercia were hard pressed by King Alfonso X of Castile and, despite the fate of the Almohads in Morocco, the governor of Granada welcomed the Merinid army, which came to the rescue. Algeciras, Gibraltar and Tarifa were given to these new allies of Moorish Spain, and from these bases they marched forth to halt the Christian offensive, recapture Seville and Cordoba and defeat and execute the Bishop of Toledo who had led an army against them.

Although the Christians were shaken by this new wave of Moorish invaders, Prince Sancho of Castile managed to hold back the Merinids’ advance, partly by the use of a burnt earth policy. And so the see-saw of the Reconquista was to continue with such anomalies as the Merinids backing King Alfonso while Granada supported Prince Sancho in a power struggle at one stage.

The year 1283 saw the Merinids return to Morocco with cargoes of treasure though they retained their territory in the area of Gibraltar which they had expanded to include Malaga. Nine years later Sancho, who by now had succeeded Alfonso X, managed to capture Tarifa and named its governor as Alonso Perez de Guzman who was destined to become a Spanish folk hero.

Soon afterwards a Christian prince arrived at Fez to the astonishment of the emir. He was John, the envious brother of King Sancho, who explained that he had a plan to recapture Tarifa with a Merinid force. To this end he was provided with an army of 5,000 and ships to take them across the Strait in 1294. When his attempt to seize the town failed, John sent a message to the city’s governor Alonso Guzman, whose only son had been placed in his service, threatening that unless Tarifa surrendered the boy would be put to death.

From the battlements Guzman shouted that there would be no surrender. As for his son’s fate he threw down a dagger to the enemy declaring that they could use it to kill him – he would rather see him sacrificed than ‘hand over the town which belonged to the King, his lord to whom he had sworn fealty.’ His words sealed the fate of his son who was killed in full view of Tarifa’s walls.

When John’s continued attempts to take the town failed, the Merinids withdrew in disgust after selling Algeciras and Gibraltar back to Granada. From then on Alonso was known as Guzman El Bueno – ‘Guzman the Good’.

Following King Sancho’s death in 1295 his brother, the traitor John, claimed the throne of Castile, which led to a civil war that dragged on until, with his coming of age, Sancho’s heir became Ferdinand IV fourteen years later. The new king devoted himself to the revival of the Reconquista and planned to capture Algeciras to close the African Moors’ traditional entrance to Spain. Thus, in the same year he gained his crown, Ferdinand besieged Algeciras and used his ships in the Bay of Gibraltar to prevent Moorish reinforcements arriving from Morocco. Supplies still reached Algeciras by means of small boats slipping in and out of Gibraltar.

To counter this blockade running Alonso de Guzman, the heroic governor of Tarifa, was ordered to take a small force and capture the walled town with a population estimated at 1,500 – royal Medina-al-Fath had never been completed. Thus in 1309 Gibraltar experienced the first of its many sieges. When frontal assault failed de Guzman positioned two siege catapults on the Rock to hurl boulders on to the buildings below. After a month the defenders capitulated on the promise of being ferried to Morocco, and so after six centuries of Moorish possession, Gibraltar belonged to Christian Spain.

3

A Chapter of Sieges

The defenders of Algeciras held out so successfully against Ferdinand IV’s forces that the King came to an agreement with the Moorish governor of Granada. In return for raising the siege he would receive two other towns that had been taken by the Moors and a large cash payment. Aware of the importance of sea power if the Moors were to be finally defeated, Ferdinand held on to Gibraltar where he planned a dockyard for his ships.

The Rock, not only barren in comparison with the surrounding countryside but dangerously poised between Moors of Granada and Morocco, held little attraction for a necessary Christian population. In order to attract an immigrant community exemption was granted from ‘tithes, toll, excise, cattle toll, watching, digging and castle service’. Sanctuary was another inducement – ‘swindlers, thieves, murderers or other evil-doers, or women escaped from their husbands, or in any other manner, shall be freed, or secured from punishment or death.’ Wrongdoers not welcome were traitors, breakers of the king’s peace and ‘one who shall have carried off his lord’s wife’.

To encourage the economy of the new settlement Gibraltar became a free port for the first – but far from the last – time. Also ships’ anchorage fees were to be retained by the port instead of going to the treasury in Castile, though ‘galleys and armed vessels that navigate in the service of God against enemies of the holy Faith’ were not to be charged.

Ferdinand IV died in 1312 leaving Castile to his year-old son Alfonso, under the regency of Prince Peter. Three years later Moors laid a brief and unsuccessful siege to Gibraltar before retreating at the appearance of a Christian force. Then in 1319 Prince Peter with his uncle Prince John marched against Granada. As they neared the city a Moorish army was waiting and they suffered a disastrous defeat in the Battle of Elvira.

Both Prince Peter and Prince John were slain, and Peter’s royal wife was taken prisoner. As a price for her freedom she offered her captors Gibraltar and Tarifa but this was rejected. Her husband’s body was hung as a trophy above Granada’s main gateway where it remained for a number of years, but due to his previous association with the Moors Prince John’s body was handed back in return for a large ransom.

In February 1333, Gibraltar suffered its third siege. Typical of the times Ferdinand’s son, now Alfonso XI of Castile, feared a rebellion and it was June before he was in a position to lead an army to relieve the beleaguered Rock. The defenders had been faced with such a shortage of food that they ate boiled leather. When the relief force reached the ill-omened Guadalete River news reached Alfonso that the governor had surrendered and sought sanctuary with his erstwhile enemies in Morocco in order to escape retribution for surrendering the Rock.

Determined to regain the Rock before the Moors could repair its defences, Alfonso launched the fourth siege by sea as well as land. Three siege catapults were hoisted up the north face of the Rock in order to bombard the castle. Meanwhile an army from Granada came to aid the beleaguered Moors but not in time to prevent Alfonso defending his rear by means of a great trench, which was dug across the low-lying isthmus that linked the Rock to the mainland. Thus the besiegers became besieged. Neither side could gain the advantage so that by winter a truce was agreed whereby Gibraltar would remain in Moorish hands for the next four years and its inhabitants would be allowed to buy food from the surrounding territory. In return Castile would receive an annual payment of 10,000 doubloons.

During the period of the truce Gibraltar’s defences were renewed, which included the rebuilding of the fortress known as the Moorish Castle whose imposing Tower of Homage, above which the Union flag flies today, remains the Rock’s most notable landmark.

After the truce ended in 1338 war recommenced when a marauding Moorish army that marched into Christian territory was defeated in the Sierra de Ronda with a loss of 10,000 men. This was followed by a second defeat near Jerez where 3,000 perished.

Enraged by these Christian successes, and mourning the death of his son in the Sierra de Ronda fighting, Abu l’Hassan, the Caliph of Fez, called for a holy war against the infidels. He ferried a great army across the Strait in a fleet of over 300 vessels before the Christian admiral Alfonso de Tenorio Jofre could intercept it.

Enemies of Jofre accused him of having accepted Moorish gold to allow their armada to enter the Bay of Gibraltar unopposed. Deeply wounded by these charges the admiral set out to prove them false by leading an inferior number of galleys and sailing ships into the Bay in a desperate attack on the caliph’s huge fleet. In the action many of the Christian vessels were destroyed or captured and Jofre met a hero’s death holding aloft the banner of Castile. When his headless corpse was hoisted to the top of a mast in sight of his sailors, galleys were abandoned by their unnerved crews who sought to escape in sailing craft.

Abu’s naval victory gave the Moors complete control of the Strait and Gibraltar, their point of entry to Spain. This sent a shockwave through the Christian world and not since the rule of the Visigoths had such a sense of solidarity infused the Christian kingdoms of Spain. This feeling of unity was emboldened by Portugal’s commitment to supply 1,000 knights for the inevitable Armageddon.

In September 1340, Tarifa, the only remaining Christian stronghold in the Gibraltar region, was attacked by the victorious Moors. They not only used siege catapults but what were described as ‘engines of thunder’, which hurled heavy iron balls against its ramparts. It was the first time cannons were used in Spain.

When the Christian contingents, under the leadership of Alfonso XI, neared Seville the Tarifa siege was raised so that troops who had been engaged in it could bolster the Moorish army. Battle was joined at the Salado River on 28 October and while the number of combatants involved is not known, the magnitude of the action can be gauged by the fact that Arab chroniclers stated that at the end of the day their dead numbered 60,000.

The fighting turned in favour of the Christians when soldiers who had been defending Tarifa appeared and attacked the Moorish army in the rear, giving King Alfonso one of the great victories of the Reconquista. A Te Deum of gratitude was sung in churches throughout Christendom by order of Pope Benedict XII. Meanwhile, the Christian companies returned to their respective kingdoms covered in glory and laden with captured treasure, the enjoyment of which eroded their dedication to the Reconquista.

With the Moors still occupying Gibraltar, King Alfonso, not content to rest on his laurels, set about mounting a new campaign that Pope Clement VI sanctioned as a crusade. As a result, adventurous – or loot-hungry – knights from all over Europe came to fight for the Cross.

English knights came under the leadership of the Earl of Derby – later the Duke of Lancaster – and the Earl of Salisbury, and proved their worth in a number of hard-fought actions. For two years the crusaders besieged Algeciras and when it was evident that Alfonso’s naval blockade would starve the defenders into submission a ten-year truce was agreed with the Moors of Morocco and Granada. The terms stipulated that the city would be surrendered and an annual tribute paid to Castile in return for safe conduct for the garrison and townsfolk to Morocco, while Gibraltar would remain a Moorish stronghold.

Alfonso was determined to reclaim the Rock when the truce ended but as it turned out he did not have to wait the full decade. Only four years had elapsed when Abu l’Hassan was deposed by his son Yusuf, the ruler of Granada. When Yusuf made an incursion into the Ronda region it justified Alfonso going to war again. So eager was the King to capture Gibraltar that he actually sold the royal jewels to finance the campaign. When his army reached the Rock he found that its fortifications had been rebuilt by command of Abu l’Hassan and its garrison strengthened by the Moors who had moved there after the surrender of Algeciras.

In the siege that followed, cannons were used for the first time to bombard Gibraltar’s walls – something that was to be repeated many times in the future. Indeed it can be argued that Gibraltar has received more shot and shells than any other fortress in history. Despite this introduction of early artillery the defenders showed no sign of weakening and Alfonso realised that hunger would be more effective than cannonballs. As autumn approached he had barracks constructed for his troops, sent for his mistress Leonora de Guzman and their children and waited for a winter of starvation to bring him victory.

The siege ended sooner than anyone expected when, in February 1350, the Black Death appeared in the Christian camp. Despite the demands of his nobles the King refused to raise the siege and evade this silent foe, vowing that he would continue the campaign until the Rock became a Christian stronghold once more. In fact, it was over a century before this came about as the plague ended his life on Good Friday of that year.

The Christian army departed and an Arab historian wrote: ‘King Alfonso was within reach of obtaining the whole Spanish peninsula yet as he besieged Gibraltar, Allah in his great wisdom favoured the Faithful in their extremity.’

When Alfonso XI died, enthusiasm for the Reconquista died with him, replaced by the usual intrigue and feuding that had bedevilled the Christian kingdoms for centuries. This time it was the hostility between the late King’s sons that ignited a civil war, which was to involve England and France. As well as having a son named Peter by his queen, Maria of Portugal, Alfonso had fathered Henry, Count of Trastamara, by Leonora de Guzman. When the legitimate heir became Peter I – known in history as ‘The Cruel’ – the resentment he harboured at the way his mother had been degraded by his father’s acknowledged parallel family found expression in revenge. He contrived to bring about the murder of Leonora, to the fury of his half-brother Count Henry and those who would have preferred him to have been their king.

In the civil conflict that followed, France supported Count Henry while England, under Edward III, endorsed Peter as the rightful king. An English force commanded by the Black Prince travelled to Spain where it defeated Count Henry’s army at the Battle of Najera in 1367. Once the victory was won King Peter showed no gratitude to the Black Prince and his men, leaving them without provisions or money to find their own way home.

The French came to Count Henry’s aid and with their help he routed Peter’s army at Montiel in 1369. It was arranged for Alfonso’s warring sons to parley. In a tent amid the litter of the battle Henry ended the family feud by murdering Peter with his dagger, after which he became King Henry II of Castile and Leon.

Previously – in one of those occasions when Christian and Muslim rulers forgot holy war for profitable alliances – King Peter had supported Mohammed V of Granada when he was deposed by an enemy who styled himself Mohammed VI. In 1362, Peter invited the usurper to Seville and then put him to death in the royal palace. Thus, when Henry slew Peter seven years later, the reinstated Mohammed V set out to avenge the man who restored him to his throne. In a surprise attack he captured Algeciras but Gibraltar was then held by hostile Moors owing allegiance to Fez.

Realising the danger of holding the city with a concentration of potential enemies based across the Bay, he razed it rather than let it fall into other hands. Yet such were the volatile politics that after this defiant gesture he made peace with his erstwhile enemy Henry II.

Gibraltar remained a colony of Fez until 1374 when rebellion broke out in Morocco and, in a reversal of past expeditions, the Moors of Spain went south across the Strait to help the caliph. In return for this aid Gibraltar was granted to Granada, but in 1410 the garrison rebelled and switched its loyalty back to Fez. The Rock’s sixth siege took place the following year when Granada won it back.

It was from Gibraltar that victorious Moors mounted raids against the powerful de Guzman family who held territory stretching from Tarifa to Cadiz. In 1436, Henry, Count Niebla, the grandson of Alonso de Guzman, who had refused to open the gates of Tarifa, raised a private army from his tenants to capture the Rock and put an end to these incursions. While half of the force, commanded by his son Juan Alonso, took up position on the isthmus, Count Henry’s vessels landed the other half on the Red Sands close to where the Ragged Staff Gate is today. What he did not realise until too late was that the Moors had built a wall between the sands and the Rock, which his men found impossible to scale while missiles rained down on them from the defenders.

The tide was rising fast behind them and soon the attackers found themselves trapped between the waves and the wall. Henry could only order his men to return to the boats that had brought them. He and a number of his knights were drowned when their boat was capsized by panic-stricken men struggling in the water. When his body was recovered by the Moors it was suspended as a grim trophy above Gibraltar’s city walls where it remained until the end of the Reconquista. Seeing the failure of the seaborne attack, Juan Alfonso withdrew and so the Rock’s seventh siege came to an ignominious end.

The eighth siege came in 1462 when Ali el Curro, a Moor living in Gibraltar, became a Christian convert. In order to be baptised into his new faith he went to Tarifa and was given the name Diego. While there he was introduced to Alonso de Arcos, the military governor of the city. No doubt wishing to prove he was no longer loyal to Islam, he informed the governor that Gibraltar was practically defenceless as a great number of its people, including the senior military officers, had gone to Malaga to pay homage to the new Emir of Granada. Here was an ideal opportunity to capture the Rock.

Governor de Arcos led a reconnaissance party and, with the newly christened Diego acting as a guide, ascended the North Face of the Rock from where the Moorish castle could be spied upon. Three Moorish soldiers were captured and they confirmed the traitor’s story. But de Arcos realised that while this was a unique opportunity to take the stronghold, once this was achieved he would not have enough men to hold it against the wrath of Granada. His solution was to obtain military support from the immensely powerful Ponce de Leon and de Guzman families, the head of the latter being Juan Alfonso who was not only the third Count Niebla but the first Duke of Medina Sidonia.

After two days of heavy fighting the Moors offered to open their gates to the Christians if they were guaranteed safe conduct to Granada with their possessions. The transfer of Gibraltar into Christian hands had the elements of a comic opera. Alonso de Arcos, being merely the governor of Tarifa, was not exalted enough to accept the Moors’ surrender – it had to be a noble, but which noble should have the honour? The Moors were willing to hand over the Rock to Rodrigo, the son of Count Juan, the head of the Ponce de Leon family. Rodrigo refused, explaining that his father and the Duke of Medina Sidonia, head of the de Guzman house, were on their way to Gibraltar and if they did not agree to the surrender terms they might prefer to take Gibraltar by force, thereby adding glory to the victory.

Knights from Jerez, who had taken part in the assault, now became impatient and privately persuaded the Moors to allow them through the gates. When word of this reached Rodrigo he summoned his cavalry and, in an unseemly race with the Jerez detachment, managed to enter the town first and raise the Ponce de Leon standard. At this sign of discord among the Christians, the Moors lost faith in the promised safe passage and fled to the castle above the town where they prepared to stand siege.