13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

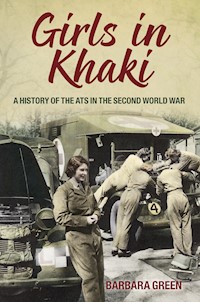

At the outbreak of the Second World War, Britain's manpower crisis forced them to turn to a previously untapped resource: women. For years it was thought women would be incapable of serving in uniform, but the ATS was to prove everyone wrong. Formed in 1938, the Women's Auxiliary Territorial Service was a remarkable legion of women; this is their story. They took over many roles, releasing servicemen for front-line duties. ATS members worked alongside anti-aircraft gunners as 'gunner-girls', maintained vehicles, drove supply trucks, operated as telephonists in France, re-fused live ammunition, provided logistical support in army supply depots and employed specialist skills from Bletchley to General Eisenhower's headquarters in Reims. They were even among the last military personnel to be evacuated from Dunkirk. They grasped their new-found opportunities for education, higher wages, skilled employment and a different future from the domestic role of their mothers. They earned the respect and admiration of their male counterparts and carved out a new future for women in Britain. They showed great skill and courage, with famous members including the young Princess Elizabeth (now about to celebrate her Diamond Jubilee as Britain's Queen) and Mary Churchill, Sir Winston's daughter. Girls in Khaki reveals their extraordinary achievements, romances, heartbreaks and determination through their own words and never-before published photographs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Acknowledgements

M y thanks go to all the ATS veterans who contributed so generously to this book with accounts of their wartime service, and to the WRAC Association Area and Branch secretaries who passed around word of the project.

I would also like to thank the following people who helped me in various ways on behalf of the organisations that they represent: Emma Lefley at the Picture Library, National Army Museum and Kate Swann and the team at the Templer Study Centre, National Army Museum who were both so helpful. Simon McCormack (House and Collections Manager) at the National Trust, Kedleston Hall for allowing me to quote from the National Trust book, Secrets and Soldiers, and Denise Young for help in obtaining the book. Jonathan Byrne, Roll of Honour Administrator at the Bletchley Park Trust for his advice and permission to quote from the Roll. Kerry Johnson and John Gallehawk for allowing me to quote from their book Figuring it out at Bletchley Park 1939–1945. Bianca Taubert of the Adjutant General’s Corps Museum for her help in obtaining ATS photos and searching out information about RAEC Formation Colleges. Steve Rogers of the War Graves Photographic Project for his advice and photographs of Heverlee Cemetery. Susan Sopala of Mostyn Estates Ltd, Llandudno. Captain S.C. Fenwick RE for all the information he provided about the HPC and especially for allowing me to see Postmen at War – an unpublished history of the Army Postal Services from the Middle Ages to 1945 by Colonel E.T. Vallance CBE ERD (late RE). The Daily Telegraph for pemission to quote from obituaries. Imperial War Museum Research Room for providing copies of two ATS War Office pamphlets.

To all those who are not mentioned, but were equally generous with their support and encouragement – thank you.

Contents

Title

Acknowledgements

Introduction

One

Organisation

Two

Recruitment and Basic Training

Three

Alongside the Royal Artillery

Four

Alongside the Corps of Royal Engineers

Five

Alongside the Royal Corps of Signals

Six

Alongside the Royal Army Ordnance Corps

Seven

The ATS on Wheels

Eight

The ATS Band (and Other Musical Talents)

Nine

A Miscellany of Vital Activities

Ten

On Location Overseas

Eleven

The ATS and Society

Epilogue

Select Bibliography

Copyright

Introduction

George R.I.

WHEREAS WE deem it expedient to provide an organization whereby certain non-combatant duties in connection with Our Military and Air Forces may from time to time be performed by women: OUR WILL AND PLEASURE is that there shall be formed an organization to be designated the Auxiliary Territorial Service. OUR FURTHER WILL AND PLEASURE is that women shall be enrolled in the Service under such conditions and subject to such qualifications as may be laid down by Our Army Council from time to time.

Given at Our Court of St. James’s this 9th day of September, 1938, in the 2nd year of Our Reign.

By His Majesty’s Command

LESLIE HORE-BELISHA

So there it was. The Royal Warrant that formally established the (Women’s) Auxiliary Territorial Service in 1938 as Britain faced the threat of war with Germany.

This is the story of those remarkable women who carried out duties, long thought to be beyond their feminine capabilities, with courage and determination. ATS girls grasped their new-found opportunities for further education, higher wages, skilled employment, management roles, and for a different future from the housebound duties of their mother and the low-paid domestic jobs that were abundant in earlier times.

Many common themes run through accounts of the wartime experiences that ex-ATS girls, or their families, relate in this book.

Training camps were set up all over the country; some recruits did their initial basic training within their home area, but others travelled long distances to areas that were unknown even to their parents. Many families had often visited only the nearest seaside resort for their annual holiday; to go from the south-east to the north of England, or from England to Scotland did come as a bit of a shock for some.

Historic houses and estates, many still owned by the original aristocratic families, were requisitioned or bought by the British government at the outbreak of war. They provided a common feature of service life. In fact, it’s not unusual to read accounts by ATS girls that mention ‘numerous huts built in the grounds to house military personnel’. Bletchley Park, which today has become one of the more famous locations, actually built its secretive structure around hut numbers only, without any description of what was going on inside them.

The most famous hut of all was probably the eponymous Nissen hut. ATS comments about these structures centre around the problems of keeping the coal-fired ‘central heating’ stove alight in the middle of the hut on a very meagre ration of coal – usually one bucket per day, not to be used until late afternoon– and around the initiative shown by the girls in obtaining additional supplies. Actually these huts were not just a feature of life in the army of the Second World War; their existence stretched for decades on either side of it. They had been designed in 1916 to house troops and were in use at least until the sixties. They were what we would now call a ‘flat-pack’ – but pre-fabricated from corrugated steel, with distinct curved walls. The hut could be adapted for use as accommodation, offices, storage or, occasionally, as a church. The next size up in the hut hierarchy was the Romney, which might be used for depot or unit storage, cookhouses and canteens or recreation rooms like those provided for ATS companies.

Ex-ATS members who describe themselves as having come from quiet, sheltered backgrounds could find the chaos and noise of their training camp disturbing. Strange uniforms, strange rules and regulations, so many other girls from so many different backgrounds, strange drill routines on a barrack square. Familiar feelings shared by anyone who has taken that first step out on to the drill square under the beady eye of a company sergeant major (CSM); or struggled to get uniform kit laid out on a bed to the exact spacing specified by higher authority; or ironed a uniform shirt to the required standard, which was especially difficult during summer months when jackets could be discarded and ‘shirt-sleeve order’ was permitted. To the uninitiated recruit this often translated as just ‘rolling shirt sleeves up above the elbow’. Not quite! The measurement above the elbow had to be exact, as had the depth of the resultant ‘cuff’ before the creases were pressed in.

One happier theme of the times was dancing. Wherever male units were located, nearby ATS groups would be invited to the dances that they arranged – in canteens, drill halls, civilian dance halls in a neighbouring town. ATS veterans remember going to dances, which offered an escape from hard and often dirty jobs, relaxation, entertainment and, not least, potential romance.

Another happy theme was the friendships that formed between girls sharing service life – the trials and tribulations, the jokes, the frustrations, the characters and antics of officers and senior NCOs. The girls enjoyed especially the off-duty gatherings for chats about possible postings, the different lives and boyfriends left behind, civilian jobs, family attitudes to their new life in uniform. Many of those friendships have survived into the twenty-first century and are probably familiar to all who have worn uniform, regardless of time and place. As one ATS veteran put it, ‘The comradeship was wonderful’.

A common experience for many ATS girls, especially those who were billeted in private houses or in properties that had been requisitioned for them in towns and villages, was the kindness of civilians. Despite all the shortages, there might be shared meals, or tea and sandwiches, even surprise birthday cakes. ATS members who volunteered for overseas service after D-Day also found friendship and generosity amongst the people of Belgium and Holland, even from those who had been left with virtually nothing themselves.

A comment that emerges only in hindsight (and perhaps with the aid of rose-tinted spectacles) is ‘I wish I’d stayed in after the war ended’. Service life was uncertain for women in 1946. There were so many men expecting to return, either in uniform or as civilians, to their old jobs, many of which had been done by the ATS during the war. Of course, many women left the service to set up home with men whom they’d married during the war, others to marry fiancés who were themselves being demobbed. Some just wanted to return to civilian life and jobs. A minority then missed service life so much that they re-enlisted.

Finally there is one rather trivial theme that deserves a mention – the supplies of hot tea that everybody remembers because they kept them going, especially when so many duties meant suffering from the cold or tiredness or both. Whether out of giant metal teapots or stainless steel buckets, drunk from mugs or jam jars or the best china in the homes of kind civilians – they seem to have a special place in the hearts of ATS girls.

It must never be forgotten, however, that while the ATS girls in khaki now recall memories of hard work and friendship, danger and laughter, they shared with the rest of the population at home that fear of the arrival of the telegram telling them that they were never again to see their father, brother, fiancé, husband or sister.

The ‘common theme’ of tea. The girls partake in tea from a lovely pot and small tea cups out in a garden or rural area. Eileen Sharp (née Horobin) is on the extreme left. Courtesy of P. Sharp.

Elsie Roberts (née Guinan) knew all about that. She was an ATS Ack-Ack (anti-aircraft) height-finder with 593 and 478 (M) HAA Batteries – and on duty at her command post when somebody relayed the message that her brother, a Royal Marine Commando, had been killed.

The skill and dedication of so many ATS members during the Second World War defined the future of women in army uniform. Despite the fact that the achievements of the ATS forestalled any return to pre-war attitudes about the place of women in the services, there was uncertainty about how their future structure should be organised.

To cover the period at the end of the war ATS members who wanted to remain in uniform were granted ‘extended service’ terms.

Discussions started about the incorporation of the service into the British Army as a regular corps. Yet it still took three years of hard bargaining before the plans were enacted. At last, on 1 February 1949, the Women’s Royal Army Corps took over from the ATS, whose remaining members were attested into the new corps. Different badges for sure, but they still wore khaki with pride.

One

Organisation

T he history of the Auxiliary Territorial Service – the ATS – really began in the middle of the First World War.

As early as 1916, in the face of heavy casualties on the French battlefields, the British government was forced to acknowledge that women were needed in the army to take over non-combatant roles from soldiers, who could then be released for front-line duties.

Consequently, in early 1917, a new voluntary service was formed – the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC). The corps received Royal Patronage in 1918, becoming Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAAC). The precedent was set.

Mrs Mona Chalmers Watson was appointed as head of the corps. Helen Gwynne-Vaughan was appointed Chief Controller WAAC (Overseas), responsible for the organisation and running of the corps’ operations in France and Belgium. She left for France on 19 March 1917. Twenty-one years later, as Dame Helen, she became the first Director of the ATS.

So who was this woman who twice took a lead in the establishment of a women’s section of the British Army?

Helen Gwynne-Vaughan GBE LLD DSc

First and foremost she was a Victorian, born as Helen Charlotte Isabella Fisher in 1879. This makes her achievements and her career even more remarkable, given the general status of women in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, when those who had the ability and the courage to do so struggled in all walks of life to achieve their potential and their ambitions.

To the horror of her parents, she took a science degree at King’s College London – a BSc in Botany. By 1909, she was head of the Department of Botany at Birkbeck College, London. After the war she was appointed Professor of Botany at London University, when Birkbeck College became part of that university. In 1911 she had married a fellow botanist, David Gwynne-Vaughan, who died in 1915.

The full story of Dame Helen’s many activities during the years leading up to the formation of the WAAC in 1917 is told in her autobiography Service with the Army, published in 1944.

Helen Gwynne-Vaughan’s work overseas in the QMAAC was so highly thought of that, in 1918, she was asked to become Commandant of the Women’s Royal Air Force to carry out a thorough restructuring of that organisation. She continued in this appointment until December 1919, when the demobilisation of the WRAF was almost complete. The QMAAC was disbanded in 1921.

Her work during these years brought the award of DBE in 1919, enhanced in the twenties to GBE (Dame Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire).

The Inter-War Years

Dame Helen returned to academia, concentrating on research in mycology, the branch of botany that specialises in the study of fungi. In 1922 Cambridge University Press published her book on this topic, the title of which has arguably only one word in it – fungi – that is either pronounceable or comprehensible for the lay reader. Interestingly, this is more than just an odd historical fact about Dame Helen’s career. In 2010 the Cambridge Library Collection (Life Sciences) republished this book for researchers and professionals as part of their scheme for reviving books of ‘enduring scholarly value’. Even in the twenty-first century she is still remembered as ‘an influential mycologist’, in which capacity she had been elected President of the British Mycological Society. Although she died in 1967, it is therefore possible to think of Dame Helen’s work as spanning three centuries.

Despite the demands of her academic career during the inter-war years, Dame Helen still found time to get involved with the Girl Guide movement at the request of Lady Baden-Powell. She progressed from the executive council to the vice-chairmanship in 1925 under Lord Baden-Powell and then to chairman in 1928. During her earlier career she had always set great store by the value of training and considered the systems of training and voluntary discipline in the Girl Guides to be ‘splendid’.

Dame Helen was also a woman who, in her own words, was ‘convinced that, in any future major war, women would sooner or later be employed with His Majesty’s Forces’. Her professorial status didn’t diminish her interest in military matters and strategy. In 1924 she became the Territorial Army Association’s representative on the Voluntary Aid Detachment Council and was also, until 1938, the chairman of the mobilisation committee. In addition she served on various departmental committees, unrelated to military matters but giving her varied and useful experience.

Discussions had been taking place since 1920 about the role of women in wartime and the need for some kind of peace-time corps of women who would be trained and ready to serve with defined ranks and military status. Progress was slow and decisions were delayed, partly through lack of funding for any new organisation. An anti-women attitude amongst all ranks of the male army probably played its part as well. Dame Helen kept in touch with discussions and developments at the War Office in relation to the employment of women in emergencies. From 1934 onwards such discussions began to take on a more formal character. As the threat of war grew ever more serious, plans for the formation of a single female corps intensified; she, however, had always argued strongly that each of the three services (army, air force, navy) should have their own women’s section, subject to military discipline.

Although the ATS was brought into existence by Royal Warrant on 9 September 1938, it was the evening of 27 September before this was made public in a broadcast by the BBC. Following a tradition of Royal Patronage, HRH Princess Mary, the Princess Royal, then accepted the position of Controller ATS in Yorkshire. In 1941 she officially became Controller Commandant ATS. Her subsequent interest in the ATS and its role within the British Army, together with her visits to ATS companies, did much to raise morale and establish the value of the service. Royalty was held in high regard at this time. Queen Elizabeth (later, the Queen Mother) was Commandant-in-Chief of the ATS from 1940 until 1949.

As the first Director of the ATS Dame Helen must have felt a degree of satisfaction in both having prophesied a formal role in the armed forces for women in any future major war and being selected, probably after some political lobbying and intrigue, to lead the female side of the army.

In her new role she was variously described as intelligent, formidable, intellectually sharp, severe, tactless, thrusting, overbearing, dowdy and an outstanding organiser who couldn’t tolerate fools gladly and made juniors very nervous. Later Dame Leslie Whateley, who became the third Director of the ATS, sought to mitigate this harsh opinion of Dame Helen after working on her staff. Dame Leslie attributed to her predecessor the foundations upon which the ATS was built over subsequent years.

Helen Gwynne-Vaughan inspecting ATS at Manorbier. Illustrates her looking ‘dowdy’ in her uniform and the ATS in the blue blazers and white skirts that they wore when attached to some RA units. Courtesy of the National Army Museum.

Yet Dame Helen’s own experiences had taught her that leading the ATS wasn’t going to be easy; she’d been exposed during the First World War, and afterwards, to the way in which many traditional males viewed any competent and determined women who wanted to invade their select circles. Indeed it wasn’t overwhelming admiration of female qualities that was the prime reason for the establishment of the women’s services and the eventual introduction of female conscription during the Second World War; and it certainly wasn’t any push from the then unknown ‘equality’ lobby. It was simply the need to release ever greater numbers of fighting troops for the front line amidst the continuing shortage of manpower.

Britain wasn’t the only country to recognise this requirement. Russia had to relinquish its traditional objection to women serving in the army because of the heavy losses suffered by its Red Army after the German invasion of 1941, known as Operation Barbarossa. American senior commanders had also had similar doubts about women serving in the armed forces, but any opposition was eventually overridden by General Eisenhower.

In addition to outside opposition to the idea of women in the armed services, Dame Helen was also aware that her age, and perhaps her old-fashioned views, might exacerbate existing difficulties. After all, she was 60 when the ATS was formed and at that time, although not today, that would be considered to be a fairly advanced age.

Subsequently she admitted that ‘the ATS got off to a bad start’. This view was confirmed by the Princess Royal in her capacity as Controller Commandant of the ATS. She wrote a preface to As Thoughts Survive, a personal account of the ATS in wartime by its third director, Dame Leslie Whateley. In HRH Princess Mary’s own words, ‘The ATS started with many disadvantages of inexperience, but with the great advantage of enthusiasm. From out of this there grew a solid regimental discipline and true military adaptability.’

In Dame Helen’s view the bad start could be attributed largely to the inadequate selection and training of the first officers; many were unsuited to the task of leadership and, conversely, those who might have been were fully occupied elsewhere. Early problems in general were often euphemistically described as ‘teething troubles’; but what did that mean?

The first factor that led to initial confusion was the existence of three women’s organisations involved in army functions in the thirties.

These were as follows. The Women’s Legion, a new successor to the Women’s Legion of the First World War. That original, private society had been formed by Lady Londonderry to provide cooks for army cookhouses that lacked sufficient staff. The girls were all volunteers but the Army Council did pay for those it hired through the Legion. It continued in existence into the thirties, by which time it had a Mechanical Transport Section. In 1934 Lady Londonderry was asked to set up a new organisation for women who might be trained in some way that would prove useful in any future emergency. She became president of this, assisted by Dame Helen as chairman, but, confusingly, they kept the title of Women’s Legion. After much discussion they decided to concentrate on anti-gas training (which only lasted for a couple of years) and officer training. In 1936, for various reasons this ‘new’ Women’s Legion was disbanded. The original Legion, still in existence, provided a Motor Transport Section.

The Emergency Service: this took over the work of training female officers under Dame Helen’s leadership. She had already set up a training school in Regent’s Park Barracks in London. Subsequently she was made responsible for setting up a more formal School of Instruction for Officers at the Duke of York’s headquarters in Chelsea.

The Women’s Transport Service – the FANY (First Aid Nursing Yeomanry): this service had been in existence since 1909 when its original purpose had been for female horse-riders to enter war zones to rescue and treat wounded soldiers. Horse riding was naturally superseded by vehicle driving so that by 1938 the FANY’s main role lay in producing motor driver companies.

Originally these three services were to form the basis of a joint army service that would be called the Women’s Auxiliary Defence Service – a title that changed on the realisation that WADS would not be a suitable acronym! The search for a title for the new women’s service proved to be difficult – either because the title could be abbreviated in an unsuitable way, such as WADS, or because the acronym was already in use if the ‘W’ was removed, leaving something like ADS – the Army Dental Service. It seemed to be a feature of military bureaucracy that whenever any new organisation was planned there would be arguments about names, titles and allocation of ranks before its actual purpose was defined. ‘Auxiliary Territorial Service’ eventually emerged as the chosen option. Unfortunately and unlike the other two women’s services, the omission of the ‘Women’ still led to some initial confusion; but as the war progressed ‘ATS’ became well known because of the contribution that its girls made to the war effort.

The second factor that led to problems, although it was thought initially to be the best option, was that the ATS was established as part of the Territorial Army (TA).This meant that it was organised, like the TA itself, on a county basis. Right from the start this caused chaos when women, hearing the calls for ATS volunteers, turned up as requested at their local TA headquarters or drill hall demanding to be enrolled. Some TA officers hadn’t even been warned about this possibility and didn’t know what to do with their new recruits. Sometimes they were told to turn up for only a couple of hours a week for basic training and to carry out secretarial and clerical duties. Disillusioned, many left at that point because they were volunteers and free to do so – exactly why Helen Gwynne-Vaughan wanted ATS recruits to be enlisted on a more formal basis.

Then there were the problems, already mentioned, with the appointment of officers. Helen Gwynne-Vaughan had always believed strongly in the need for leadership training for officers, that was why she had organised it in the Emergency Service. So what was the difficulty in the early months of the ATS? Again it related to the link with the TA. When they realised that there was a need for ATS officers they thought that the easiest source would lie in the county structure of titled ladies and wives of local dignitaries and landowners who, with many other ladies, were well known in the county for their voluntary and charitable work. In the TA’s predecessors – the Militia and the Yeomanry – this had been the method of appointing male officers for as long as those military formations had existed but this solution obviously had pros and cons for the ATS. None of the above criteria could guarantee leadership potential or any of the other qualities required for officers. So there was justifiable criticism of the competency and efficiency, or lack of it, amongst the officer community of the ATS. As one ATS veteran described it, ‘They were useless and only got an immediate commission because they were society girls’. However, there were many officers who quite rightly felt that generalisations like this were grossly unfair. Such comments were resented by the leaders of platoons and units that were well organised, active, smart and gave a good impression of the service in front of the general public. These officers probably had some kind of previous experience that could be developed into leadership with more specific training.

As the number of ATS recruits grew rapidly from the initial 17,000, the question of officer competency had to be tackled officially. Those who were plainly unsuited for the positions were discharged as quickly as possible, thereby making room for efficient junior ranks to be promoted; this also had a beneficial effect on morale. Confidential reports were instituted for all officer ranks. The number of ATS Officer Cadet Training Units (OCTU) was expanded to provide the hundreds of officers, both technical and regimental, who were needed. Reactions to the subject of ‘officers’ vary. Many ATS weren’t interested in the squabbles and politics of higher command; for them the most important event involving a senior officer would be a visit by the current director, especially if she was accompanied by royalty. Their platoon or unit officer would have the most influence in their day-to-day lives. Most of them were ‘quite nice’ or ‘very helpful’; but one obviously failed the test – after more than sixty years she was remembered by an ATS veteran as simply ‘a bitch’!

Equally important was the training of NCOs; one aspect of a first promotion to the single stripe of a lance corporal was how to cope with the move from being one of the crowd to having some authority, albeit slight, over that crowd, without alienating anyone. Another reason for the urgent need to recruit and train officers and senior NCOs was to enable the hundreds of ATS recruits to be trained by female instructors rather than by men.

On top of all the practical problems of organisation, administration and training there was the relationship between the long-established FANY and the newly formed ATS. This, inevitably, proved to be a very difficult situation, not helped by the deep personal animosity between the leaders of the two organisations. Mary Baxter-Ellis, Commandant of the FANY, and Helen Gwynne-Vaughan were both veterans of the First World War but despite that, or perhaps because of it, they now appeared to be sworn enemies.

In addition, members of the FANY thought themselves to be far superior to those girls who were joining the ATS. They wanted to remain independent of the ATS and continue to run their units as they always had done. Indeed, for a while they did do this while the ATS was trying to sort out its own problems. The FANY, with all its experience of motor transport, was training drivers within its own organisation virtually independently of the ATS. As if this wasn’t bad enough, the ATS was run according to military tradition and regulations, which meant a strict division between officers and ‘other ranks’; the FANY had no such restrictions, which absolutely infuriated Dame Helen. She brought certain beliefs with her into the new era but she had to fight hard for her ideas. She wanted enlistment for her women, not enrolment as volunteers. (This was one of the few areas in which she had the support of Miss Baxter Ellis of the FANY.) She also wanted payment, which she saw as an essential element of being able to impose discipline on those who were simply volunteers. It’s not too difficult to imagine all the squabbling that took place, even while the country remained under the threat of war.