7,03 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Dolman Scott Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

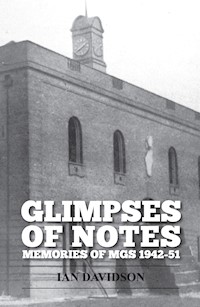

In Glimpses of Notes Ian Davidson describes in remarkable detail his education at Manchester Grammar School, beginning during the second half of World War Two. A native of Broughton-in-Furness, he brings his acute observational powers to bear on his upbringing in this great northern industrial city and his education at one of the world’s great schools. Starting in the Preparatory Department and leaving from the History Sixth Form, he produces wonderful sketches of his fellow pupils and teachers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 409

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Published by The Development Office of the Manchester Grammar School in 2016

Copyright ©The Development Office of the Manchester Grammar School

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner. Nor can it be circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without similar condition including this condition being imposed on a subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-1-911412-05-2

eBook Apple: 978-1-911412-06-9

eBook Kindle: 978-1-911412-07-6

The Development Office of the Manchester Grammar School is an imprint of

Dolman Scott Ltd

www.dolmanscott.com

Reactions to Glimpses of Notes by some other Old Mancunian authors

Ian Davidson is an excellent writer who has an astonishing memory for detail.

He paints a fascinating, vivid portrait both of his days as a schoolboy at MGS in the ‘40s and early ‘50s, but also of life amid the rationing and thick fogs of wartime and immediate post-war Manchester.

Although I went to MGS a generation later, his book brought back floods of fond memories.

Michael Crick

It’s an achingly familiar world conjured up by Ian Davidson: the seat politics of the school bus, the threat of a Saturday morning punishment, the ‘problem of women’ occupying the minds of pimply schoolboys. Reading this transports you back to Old Hall Lane - a vivid sensory experience of jostling in corridors, ink wells and raiding other classrooms.

Yet, just as you slip into warm familiarity, the book jolts you into historical reality; that this was taking place not in your own youth, but against the backdrop of World War Two. The blitz damage: the scarred Manchester when the author went to buy his uniform. The blackouts. And, most poignantly, the reaction of the Jewish boys at school once word of the Holocaust began to emerge; some took to wearing yellow stars in solidarity.

Rich in detail, this is a gripping piece of social history that captures a school-life straddling the War. From the momentous, to the fascinatingly mundane - the emergence of the nascent biro supplanting the fountain pen, local lasses inexplicably being drawn to the brash GIs who stayed on in England.

It is also the thoughtful and candid reminiscence of a man looking back at his formative years - without any rose-tinted lenses.

And one is left with a lingering sense of how soft we are these days. As the author notes, when he went back to visit the school, ‘Today’s generations seem composed and sedate, whereas we were rough and rowdy as we trooped from one classroom to another’.

A thought-provoking, highly-engaging and unique piece of work.

Tim Samuels

A lively, personal memoir of an important decade for the School. Ian Davidson writes with a glint of amusement in his eye and an admirable memory for the little details that make such accounts come alive.

Martin Sixsmith

I am younger than Ian by fifteen years and you might have thought the experience of my generation, in the first half of the sixties - ‘between the end of the Lady Chatterley ban and the Beatles’ first LP’ (when ‘Life was never Better’!) as Philip Larkin put it - was a long way from his: a childhood and schooling in the shadow of war, prep school in the Manchester Blitz. But not at all. Ian’s memoir is so poignant, affecting and extraordinarily evocative; but his Manchester was still ours in the early sixties. He has caught the temper of the time spot-on: the bomb-damaged city now in decline, the great age of Manchester over, or so it seemed; the breathless new age of the ‘original modern’ as the City rebranded itself not long ago, yet to be born.

But this was the moment when, after such a long and distinguished engagement with the community of Manchester, over 400 years after all, MGS rose to become the finest school in Britain, way ahead in academic results, topping Eton, Harrow, Winchester and all the rest; but the best in so many other ways too, it seems to me. It was a perfect conjunction of circumstances with a brilliant generation of teachers; some already in place, some to come under the charismatic Eric James, whose arrival and bedding-down period Ian vividly paints for us. All of my generation too can remember the presence of ‘the Chief’ by the touchline, or watching in the darkness at the back of the theatre at an after-school rehearsal: it seemed to me, in Middle School, like the proverbial emperor who never slept!

The book is full of fabulous detail: the texture of life in the post-war city, with the Manchester Guardian, the Hallé, and Lancashire Cricket; the texture of life before the age of Twitter and iPhone. We watch in intimate close-up the growth of a person’s consciousness; the teachers, the books and ideas that changed his life, from Shakespeare to Baudelaire, Rimbaud and Hesse. As Ian says, our teachers thought ‘our heads were bottomless buckets that would take whatever was poured into them.’ There are, too, the deftly and humorously sketched markers of growing up: Gitanes in Birchfields Park, the first fumblings of sex, and the hilarious portraits of the more eccentric teachers like the sadistic Billy Hulme; or Simpkins with his great line about learning to make bricks: ‘it’s a boring business, boys, but soon you’ll be able to build something, and that can be fun!” Fun it was, as I remember, too; as Ian says, ‘we learned without realising it.’

For me the book will take its place alongside Bryan Magee’s Clouds of Glory (the tale of a Hoxton childhood) or James Walvin’s recent memoir of his forties upbringing in Manchester, Different Times. Old Mancs will love it - but so will historians, too. It is about the making of a person, as well as the story of a school, and one hopes it might inaugurate a tradition where members of future generations who may also be gifted with Ian’s incredible recall might leave their memoirs to posterity too?

The biggest message I get from the book is this. As I get older I value more than anything else the great gift to us from the teachers who shaped us, guided us, and opened our minds, often to worlds we never even dreamed existed. Ian writes: ‘whatever I have of intellectual curiosity, benevolence, academic rigour, sociability, and good humour was fostered at MGS’. That is so true. And how important is that word benevolence. From now on, for me, the abiding memory, thanks to Ian, will be benevolence.

Michael Wood

Other books by Ian Davidson

Dynamiting Niagara

or Coming of Age in Broughton Mills

(2005)

A Hatful of Crows

Culture and Anarchy in Broughton Mills

(2007)

More Like London Every Day

or Being and Becoming in Broughton Mills

(2010)

Whisky with Mother

or The Uses of Literacy in Broughton Mills

(2015)

GLIMPSES OF NOTES MEMORIES OF MGS 1942-51

by IAN DAVIDSON

Forty years on when afar and asunder

Parted are those who are singing today,

When you look back and forgetfully wonder

What you were like in your work and your play;

Then it may be there will often come o’er you

Glimpses of notes like the catch of a song -

Visions of boyhood shall float them before you,

Echoes of dreamland shall bear them along.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

FOREWORD

PART I - THE PREP DEPARTMENT 1942-44

1. PRELUDE

2. BEGINNINGS

3. PREP 1 (a)

4. BOWKER’S BUS

5. PREP 1 (b)

6. THE CITY

7. PREP 2

8. THE WAR

9. WEEKENDS

10. MEMORIES

PART II - GROWING UP

1. THE MAIN SCHOOL

2. MR MORETON

3. THE WAR AGAIN

4. DISGRACE

5. CLOTHES

6. THE END OF THE WAR

7. Iα

8. MORNING BREAK

9. THE CHIEF

10. IIα AND SIMKINS

11. REPORTS

12. LUNCHTIMES

13. TRAVELLING

14. LANGUAGE

15. BILLY HULME

PART III - THE MIDDLE SCHOOL

1. PREAMBLE

2. EDUCATION: iiiα

3. ME AND GOD

4. JEWS AND CHRISTIANS

5. SUTTON

6. GLIMPSES OF THE WIDE WORLD

7. MUSIC

8. FAT FREEMAN

9. SPORT

10. SCHOLASTICS

11. AND SO TO Rα

12. LEARNING

13. LUNCHTIME PROMENADE CONCERTS

14. EXAMS

14. SCHOOL CERT.

PART IV - LIFE IN THE SIXTH

1. HISTORY SIXTH DIV III

2. SUNDAYS

3. HAUTE COUTURE

4. WORKADAY WORLD

5. THE CHIEF

6. GROWING UP

7. SUMMER OF 1950

8. FLIRTS

9. THE LAST DAY

EPILOGUE

PREFACE

We are delighted that Ian Davidson chose 2015, the 500th anniversary of the foundation of MGS, to complete his substantial memoir of his time at the school during World War 2. Remarkably, readers who have known the school since then or who know it today will find that much has not changed. Ian’s MGS lived out both the school’s motto, Sapere Aude (Dare to be Wise) and the inscription placed on the foundation stone of the buildings in Rusholme when the school moved there from central Manchester after 416 years: ‘The place changes, but the spirit remains the same’.

We are grateful to Ian for his excellent memory and his engaging narrative style. Moreover, he has generously donated the proceeds from this book to our Bursary Fund, so vital to preserving future access to MGS for clever boys from poorer backgrounds.

As High Master, I am particularly taken by Ian’s account of the circumstances in which my predecessor Eric James arranged for him to leave. I do not expect to have such a conversation with any of my pupils so, in some ways, times have changed.

Martin Boulton

FOREWORD

Most of us remember our schooldays – sometimes vividly - so it is curious how few memoirs of this crucial phase of our lives are written. Most biographies or autobiographies devote no more than a chapter to this period of life and many scamper over those formative years in a page or two. In the case of Old Mancunians there has until now been only one full-length book devoted to their time at school – Ernest Barker’s The Father of The Man (1948) – a wonderful evocation of the great scholar’s years at MGS in the late 1880s and early 1890s. Otherwise we have only a few scraps to reveal what the school was really like in the past.

The first OM to record his (unhappy) time at MGS was Thomas De Quincy but his hostility was balanced by Harrison Ainsworth, almost a contemporary of De Quincy in the early 19th century. In his novel Mervyn Clitheroe the school appears much more benign. And so it continued with various writers recording briefly their happy or unhappy memories of the place. The most recent memories come from the scientist and clinician Michael Lee (Stood On The Shoulders of Giants, 2003) and the art critic Michael Baxandall (Episode – A Memory Book, 2010). Both are revealing but lacking in detail.

Perhaps the most famous school memoir of all is Alec Waugh’s The Loom of Youth (1917) –a fictionalised account of his five years at Sherborne School. It caused a scandal at the time but seems rather tame stuff now.

Ian Davidson’s Glimpses of Notes is quite exceptional in that it combines the best elements of all previous attempts at recalling both the delights and horrors and also the numbing boredom of one’s time at school. Having entered the Prep Department of MGS aged nine in 1942 he spent almost a decade at Rusholme – an unusually lengthy stint. As the years passed he grew from a naïve youngster through the pains of adolescence to an independently minded young man. We follow his progress in astounding detail – his description of the school in all its aspects is vivid and revealing – the buildings, the daily routine of lessons and break times, the long journeys to and from home. His teachers and his fellow pupils are all recalled in an amused and unbiased style that is truly unusual. We learn of his friendships and occasional enmities, his growing love of learning, his occasional tussles with authority but above all of his observation of what was going on around him. No account of MGS life has ever matched his extraordinary powers of recall.

But Glimpses of Notes is far more than a school story. Whilst his life at MGS occupies centre-stage, it is set against the background of the Second World War and the period of austerity that followed. We see the impact of the war not only on the school but on his family and on Manchester itself. Written from a youngster’s point of view there are echoes of John Boorman’s brilliantly poignant film Hope And Glory (1987) as young Ian takes shelter from bombing raids, plays war games with his friends, samples the delights of a rationed diet or makes his way through the bombed-out suburbs of the great city. Here we have a social history of what growing up during the war was like. The snail pace of post-war improvement in living standards and opportunities is also brought to life as Ian discovers train spotting, cricket and the delights and perils of the opposite sex. And finally it should be noted that although a city dweller for most of his formative years, Ian was a country boy at heart. Born in Broughton Mills in the south Lakes where he spent his early years and with family still there, he always hankered for that most beautiful of landscapes and after a long career in various academic posts he has retired to the area that he loves the most.

Jeremy Ward

PART I -

THE PREP DEPARTMENT 1942-44

1. PRELUDE

I don’t visit Manchester much now, but when I do I make time to go to Rusholme. On the way there, I think not much has changed. The bare bomb sites along Upper Brook Street have been built on, but from Plymouth Grove it is much the same. However, Victoria Park is barely recognisable, the big houses with lawns and tennis courts have been turned into flats and their gardens built on. Dickenson Road and Birchfields are much as I remember them. Coming back to town along Wilmslow Road and Oxford Street things have changed almost beyond recognition, and once past Whitworth Park and the Art Gallery I am lost among new buildings and new roads that form part of the new city. Then, before I realise it I’m on the Mancunian Way and off to wherever I’m really going. But between these fleeting scenes, I contrive to be driven slowly along Old Hall Lane where I can take in a panorama of the school.

The main building is much as it was: solid, imposing, its clock tower rising above Hugh Oldham’s hatchment and the great archway leading to the main quad. Wings and annexes have extended the frontage and a fine pavilion faces the first team pitch. From the main gate, still guarded by owls, the drive has been turned into an avenue with a row of trees on either side. But it is still comfortingly much as I remember and the sight takes me back to the days when I was a small boy and wore a dark blue cap with light blue rings and a little metal owl on the front.

Although my antecedents are Scots and Cumbrian, and I was brought up in the South West corner of the Lake District, I have always known that I was part Mancunian. I was born in the city and most of my formative years were spent as a pupil at MGS. There my mind was filled with the knowledge and ideas that shape the developing life, and I guess that whatever I have of intellectual curiosity, benevolence, academic rigour, sociability, good humour was fostered, if not planted, in those early years. Then were laid foundations for an Oxford education and a modest career as a minor academic. On the other hand, that early training must in some way be also responsible for the garrulous, argumentative, bibulous, gregarious, old sod I think I’ve turned into – which is perhaps not really what the school intended. Whatever it did it couldn’t whip the old Adam out.

As I write about my time there, over sixty years ago, I wonder how much of what I remember actually happened. More and more I feel that what is recalled is partly wish-fulfilment and partly justification, and that the recherche du temps perdu is fundamentally a desire to give significance to the random effects of time and accident. I ask myself, ‘What did it all signify?’ And to hide my uncertainty, I construct a satisfactory story out of what I think I remember about what might have gone on, while accepting that someone else who shared that time and place with me would produce an entirely different tale. As Fichte said, imagination is not memory but a means of communication, the self-expression of the individual, the portrayal of a private world.

I remember my days at MGS with great affection. That’s not to say that every day was sunny, for there were black periods and unhappy times, but all in all I was glad to be there. I was barely nine years old when I began, a bewildered, bookish boy with a country upbringing. When I finished I was less bewildered, but also cocksure, strongly aware of my own individuality and not inclined to heed authority. I began in Prep 1 in September 1942, and left in June 1951, having been in Prep 1, Prep 2, iβ, iα, iiα, iiiα, Rα and History Sixth divisions (iii) and (ii). Few pupils, I guess, can have spent so long under the wings of Hugh Oldham and his Owl.

Of the beginnings, my memories are patchy and vague, the mists of time swirl round events and people, part revealing, part obscuring. Like family photographs of dimly remembered places and events, they must be enlivened with stories that give them continuity and a sense of being. Some older actor in the scene must say, ‘That was just before your father blew up the primus stove,’ or ‘You fell out of the boat after that.’ The figures need to be given speech and the facts need elaborating. At least that’s how it is with me: I need a story.

In the Oxford Schols I sat in 1952 I was asked: ‘Is the Historian a Novelist manqué?’ Until that time I’d never thought of history as literature, but as I balanced Stendhal and Thackeray against Wedgewood and Woodward, I saw immediately which kind I preferred. The novelists gave me a better idea of Waterloo than Gronow, who’d been there, or Creasy who’d read everything about it and discussed it with survivors. Wedgewood and Woodward were from another era and their dry analyses did nothing to inspire a vital understanding of the action. However, Julien Sorel and George Osborne were figures I could believe in: the account of the one’s bewildered wandering over the battlefield and the stark announcement of the other’s death provided me with a more satisfactory understanding of what went on than the lists of facts and figures provided by the historians.

I was much intrigued just then with Shakespeare’s line in “The Phoenix and the Turtle”: ‘Truth may seem, but cannot be’, which complemented Touchstone’s remark in As You Like It that ‘the greatest truth is the most feigning’. Both – one a solemn pronouncement, the other a throw-away remark – were sharp stabs at pinning down the Proteus I saw as Truth. They persuaded me that I had to make sense of truth from the inside, because it wasn’t out there. And so, I present these reminiscences as partial and inside views of the character that is me. They purport to record authentic times and places and actual events, but in the end they are only stories.

2. BEGINNINGS

It was on my father’s insistence that I became an Owl. He was a Scot by birth, a Geordie by upbringing and a Mancunian by adoption. Like me, he spent a particularly rich and rewarding period of his life there. He came in 1919 after service in the Flying Corps and spent six years in the Manchester University Medical School, going on to specialise in infectious diseases. Thus he stayed to work in the city’s isolation hospitals where his professional interests lay in managing, until he met my mother, to pass his winters with Hamilton Harty’s Hallé at the Free Trade Hall, his springs at the Opera House and his summers at Old Trafford watching Maclaren and Spooner. In between there were the Whitworth and the Mosley Street galleries to see and Miss Horniman’s theatre to attend.

After qualifying he was on the staff of Monsall isolation hospital in Collyhurst, where he met and married my Cumbrian mother. This, as she often told the family, ended a promising career in Nursing, where one with her undoubted managerial skills would certainly have succeeded. As I was growing up, I noticed that she was always ready to contradict or at least disagree with any medical opinion my father cared to offer. At length, he would demur when any of the family consulted him. ‘You’d better go and see the doctor,’ he would say, ‘she knows far more about these things than I do.’

I was born in the Manchester Royal Infirmary, over the weekend of the Roses Match in July 1933. My father was in constant attendance, mostly at Old Trafford. This rankled with my mother, and fifty years after the event she still enjoyed mentioning it. My father always felt absolutely justified in his absence. ‘Young Cyril Washbrook made his first century,’ he said. ‘And there was nothing I could have done for your mother even if I’d been there. Far better let them get on with it.’

In the troubled times leading up to the second world war my mother, together with the infant me, moved back north to care for her ailing sister and failing mother. It was what youngest daughters did in those days, whether they’d been trained as nurses or not. The family lived in Millom, a small town with an iron ore mine of prodigious richness and an iron works, just across the Duddon estuary from Barrow in Furness. Already people were fearful of the effects of bombing in cities, and those who could fled to the country. The shipyards at Barrow were sure to be a target, and along with them, the iron works at Millom, and so our family came to settle on the outskirts of Broughton in Furness, nine miles from where my mother was born. Here, in a closely connected community of relations and friends, was the centre of my childhood and it was from here, after a strange year at the beginning of the war at school in Dumfries among my father’s relations, that I was transported to MGS.

Moving to a city from the security of the countryside at a time when bombs were still falling might have seemed an act of madness. Manchester was recovering from its Blitz, Trafford Park was still a target for the enemy, and the region was still a dangerous place. Nevertheless, I was glad to leave my Scottish Prep School where the sum of my remembered learning was that the Scots beat the English at Bannockburn in 1314. My Scottish aunt with whom I stayed was rather cheerless, and my cousin John had an infuriatingly supercilious manner. I recognised it as such when I came across the word much later and saw in his behaviour its perfect definition. Despite being called Ian Scott Davidson and wearing a kilt in my clan’s tartan, I never felt Scots in any way, nor did my classmates let me forget that I was different. I was rarely happy in Dumfries and felt myself to be in a sort of limbo – another word that I was later able to fit to an experience I was glad to be delivered from.

The first inkling of the new life was when I was brought to MGS during the Easter holidays. I must have been told what was happening, but I was noted, even then, for being able to disassociate myself from what was going on. News of visiting relations or a shopping trip would send me off to the woods with a store of apples and a book. Notice of the Entrance Exam must have been kept from me until the actual event. It was sprung on me on a bright sunny day, when I was summarily brushed up and changed and whisked with my father to Manchester to stay with an old University friend. The following day I was taken to Rusholme and plunged into an echoing cavern of a building, bewildering with noise and people. The staircase was crowded with grown-ups coaxing, chivvying would-be owlets. It was a brave new world that impressed me by its order in confusion. Soon, I was settled in a desk where I did some sums and wrote a composition. I was good at compositions and bad at sums. From time to time I focused my attention on Miss Robins who was firmly in charge. I was also impressed by the manner of a boy I came to know as Rawley who said, cheerfully, ‘Blowed if I know,’ in answer to a sharp question from her. It appeared to fox her, for a moment.

Weeks afterwards, when I was told that the school would have me, I was alarmed by the thought. From time to time during the summer I was uneasy when people said, ‘At your new school…’ and I would shut my ears and run away, for it was something I didn’t want to think about. Towards the end of the holidays I had a taste of what was to come when we made another trip to Manchester to buy my school outfit. During this visit I was set to learn ‘Hugh of the Owl’ by one of my mother’s friends who had a son at the school. She said that knowing the school song was a necessary part of being a pupil and I ought to learn it before I became one. I was good at memorising poetry and learnt it so quickly she wouldn’t believe me until I recited it. ‘Tom doesn’t know it yet,’ she said, ‘and he’s going into the Main School. You’d better learn “Forty Years On”,’ which I did, thus earning Tom’s lasting enmity.

It was only when I was taken to buy my school uniform that I realised the full significance of what was happening, for in those war-time days buying clothes was a serious matter. It was a hot summer day and we walked from the station, through the canyons of Corporation Street to the rubble strewn wastes that stretched from the cathedral to Cross Street. It was explained to me that this was where the bombs had fallen. It was my first proper view of the horrors of war. Hitherto they had only been pictures in the papers and cinema. A sight of the real thing disturbed me: a house affected by a direct hit which had left the rooms exposed, sitting room, bed room, with all their belongings open to the weather and the world’s eyes. ‘What about the people?’ I imagined how it would be if my bedroom had been blown up and my things, my model aeroplanes, books, clothes, all scattered and spoiled. Nightmare thoughts troubled me in the quiet of St Anne’s Square, clashing with the primness and order of Henry Barrie’s Gentlemen’s Outfitters and Bespoke Tailors. That night I had troubling dreams and the scene of devastation haunted me for a long time. For years it remained a disturbing memory which I shied away from.

3. PREP 1 (a)

The Prep Department occupied the two rooms at the top of the main staircase. I was directed into Mrs Gaskill’s. In the other was Miss Robins. These rooms were in a little recess, with a radiator on one side, round which we huddled in winter, and when it wasn’t cold we would hang over the banisters, flying paper aeroplanes down the stair-well and cheeking our elders as they came up the stairs. Sometimes our activities would attract the attention of a master on his way into the Staff Room and he would terrify us by coming to the bottom of the stairs and glaring. I once proposed a slide down the bannister, which was spiked at intervals with brass studs. ‘Rip yer ballocks off,’ Williamson said. I still wasn’t quite sure what ‘ballocks’ were, and wouldn’t, then, have considered them as an impediment to a slide. It was the fear of the dizzying drop to the basement that put me off.

In the Prep we were MGS boys with a difference. Our caps had red rings on them rather than blue, and similarly red stripes on our ties. Our caps bore the little metal Owl of Athens – I still have one – which could be used to inflict a nasty scratch if the cap was folded in the right way. We wore grey shorts, with a grey pullover and grey shirt, stockings and black lace-up shoes.

My father took a commemorative photograph of me kitted out on my return from Henry Barrie’s – ‘I might never see you looking so respectable again, boy,’ he said. He always called me ‘boy’. A fortnight before he died at eighty-eight he said, ‘I’ve had enough, boy.’ – I look hesitant and uncomfortable, poised as if ready to take flight. My teeth show on the corner of my bottom lip and I’m not looking at the camera, but at the door.

Unlike Miss Robins who was red-haired and busy and had a taste for bright clothes, Mrs Gaskill was quiet and sedate. Grey hair and grey dress, with spectacles, I wondered whether our school uniform was modelled on hers or hers chosen to conform with ours. But her manner and teaching were far from grey. She could quell with a glance and control with a whisper, and had no trouble at all with Rawley, whose imperturbability was a model for us all. He was confident and affable with a shock of hair that seemed to burst out round his head like foliage – except it was yellow rather than green. Miss Robins, whom he’d briefly fazed, could put on a spectacular display of fireworks if he provoked her, but Mrs Gaskill was quietly firm. Her strongest expression of disapproval was a quiet sigh, which showed us that we had disappointed her. Her room had windows on two sides and it was often flooded with morning sunshine. At such times she would make us do deep-breathing exercises. ‘To keep you brisk,’ she said.

I remember little of the actual lessons. We learned without realising it. Knowledge, it seemed, was simply absorbed. Most of the time, I think we educated each other. Mrs Gaskill simply facilitated the process, largely by reading to us at the end of each day. Thus I was introduced to Ivanhoe and Bevis and Wind in the Willows and Cranford, which I took to be about her own life, because she’d told us she came from Knutsford and I wondered whether the lace collar she sometimes wore was the one the cat sicked up. She read us a lot of poetry too, from an anthology called The Poets’ Company which I still have, scuffed and tattered with ‘I Davidson. Prep One’ blottily written on the inside of the front cover. I loved the bouncing rhythms of The Pied Piper of Hamelin and soon had most of it by heart, though the rats biting the babies in their cradles made me squirm. In Morte d’Arthur, the ‘great water’ was one of the Lakes and even now, whenever I fish on misty mornings I expect an arm ‘clad in white samite’ to reach through the surface and catch a whirling sword. I didn’t much care for Wordsworth: no music, and his ballads weren’t like Sir Patrick Spens or The Wife of Usher’s Well. At home, under the tutelage of my mother and my aunt, much emphasis had been put on learning tables and spelling and poetry. Before I came into Prep I, I could recite the whole of The Lady of Shallot, most of the verses from Now We are Six and large chunks of Belloc’s Cautionary Tales. This gift won me favour with Mrs Gaskill and went some way to mitigate my ineptitude at maths.

My friends in Prep I were Williamson and Lewis, and I learned much from them. Lewis and I swapped things. I was interested in his stamps and he in my dinky toys – a battered collection handed down by my cousins, but very acceptable at a time when they were no longer being made. We traded covertly, often in class, by passing notes and agreeing deals, sometimes in cash, which we settled at break. He taught me how to do percentages and work out averages, passing me his exercise book showing how they were done. In return, I would prompt him when he got stuck with the poem we’d been set to learn. He was numerate and I was literate. After Prep II I’d nothing to do with him until we met in the Sixth – he in Maths and I in History. We had a short embarrassed reunion, then we went our own ways.

Williamson and I were at opposite sides of the room so we only communicated during breaks. At lunchtime, we would race away to Potts’ shop on the other side of Birchfields Road and look at things we might buy. Around Potts’, on the Meldon Road, there was a small shopping centre, which was somewhere to go out of school. It was always fairly crowded with boys wanting to escape from the atmosphere of order and restraint and get back to the real world. The wide pavements would be crowded with knots of boys, chatting and arguing. It was as if they felt the air was free-er here in the outside world. Behind the shops was a maze of paths and ways through a large housing estate which reached up to Stockport Road. Here would wander those in search of a quiet smoke.

On Birchfields Road itself there was a pie shop which always attracted a crowd at dinner time. Williamson and I both had to buy dinner tickets and seldom had cash to be customers there, but we would always pause to gaze through the window and watch enviously as those coming out of the shop tossed hot pasties from hand to hand to cool them down. A great tail of MGS boys stretched across the pavement waiting to get at the trays of tarts and cakes which vanished almost as soon as they appeared. Once, while the girl was fetching some more, a knave in the queue leaned over the counter and stole a tart. As he popped it into his mouth, there was a murmur of disapproval which grew as we watched his bulging cheeks grow less. When the girl came back the queue fell suddenly silent and she sensed something was amiss. No one peached, but she knew, and we knew, and the culprit knew. Ever after he was marked. In the sixth, I saw him in the library and someone said, ‘That’s the tart man.’

Williamson and I were close and confidential for a while. We stayed at each other’s houses and confessed our ambitions. He wanted to be a pilot and fly to the moon, I wanted to be a civil engineer and build bridges. ‘I wonder what it’ll be like in 2000?’ he mused one night. ‘Do you suppose we’ll be still around?’ ‘Doubt it,’ I said. ‘You’d be sixty-seven then. One of my uncles is sixty-seven and he’s as good as dead.’ I liked Williamson a lot because he had an inquiring mind and his conversation was full of ‘What ifs?’ rather than ‘I’ve got...’ or ‘I can...’ and ‘You can’t...’ He was a comforting complement to the friends I had travelling to school on Bowker’s bus.

Like Lewis he went into a different side in the Main School and I lost touch with him until we’d both left. Then we met at a dance in the MRI Nurses’ Home. It was quite a formal affair and attended, in the early stages at least, by the Matron, to whom the guests were introduced – to see if they were suitable, I presumed. I was at Oxford, and he was a Pilot Officer, so we were all right. By then all thoughts of building bridges and making roads had been dispelled by my developing ambition to write a successful verse drama in the manner of The Lady’s not for Burning. Williamson was learning to fly faster and faster planes. ‘What about the moon?’ I asked him. ‘Mm,’ he said, ‘we’re getting there. I guess these German rocket men’ll teach the Yanks how to do it. They’ve got the brains and the Yanks have the money. There’s some bastard cutting in on my girl. I only sat this one out so’s I could have a smoke.’

Despite Mrs Gaskill’s deep-breathing exercises, on sunny mornings I often found it difficult to stay awake. When the sleepiness became insuperable, I would ask to be excused and have a stroll down the cool corridor, listening to the teaching voices behind the closed doors. The smooth floor stretched empty into the distance between uniform grey doors on one side and windows on the other. Looking onto the side of the Memorial Hall and shielded from the morning sunshine by its bulk the vacant corridor reached into as yet unknown regions. Here were dens of ogres, lairs of tyrants whose names were heavy with ill omen – Chang Lund, Harry Plackett, Billy Hulme, Killer Maugham. Sometimes I would stray down the corridor and listen at the doors, trying to fit voices to the names I’d heard. On the way back I’d linger for a while in the toilets, making a perfunctory effort at a pee which I didn’t really need.

In the room directly opposite the toilets Johnny Lingard taught 3C, a notoriously difficult class. It included Catterall, famed for insubordination and slovenry. I knew him from Bowker’s where he often mentioned Johnny Lingard in an aggrieved and sceptical way. ‘He goes to bed at twelve and gets up at four,’ he said. ‘It’s so’s he can get the most out of life, he says. He’s barmy.’ Unlike the droning voices that came from most rooms, Johnny Lingard’s rose and fell in waves of impassioned sound. I would pause and listen for a while, in case he gave way to one of his famous dramatic outbursts. I knew him by sight as a wild figure rushing past the Prep Department, spectacles flashing, gown flying, as though he were pursued by the Furies – I’d read about them and heard my father say they were a set my mother belonged to.

Years later when I was in iiiα and a member of the Gramophone Society, I came to know and like him. He was the Society’s Staff Member and our weekly meetings were held in his room because that’s where the gramophone was. It was there I was introduced to the symphonies of Mahler and Sibelius which were the preferred listening of most members, though mostly I remember we listened to Beethoven. Johnny Lingard was an enthusiastic proselytiser for Baroque music, some of which he insisted on playing at every meeting. It was thus I first gave a serious hearing to Bach, which I never heard at home. Even now, the jingling harpsichord at the beginning of the fifth Brandenburger transports me to those times and in particular, a winter Thursday afternoon when the fading blue of the sky was etched with the darkening shape of the school clock tower. I sat, sprawling over the desk, half on the seat, half off, bemused by the mathematical certainties of the coda before its return to the main theme.

Lingard was a man of strong views, which he strenuously expressed. He had a disdain for Wagner – ‘Hunnish belching after sausages,’ he declared – and scorn for ballet music which he said was musical syrup, only played so dancing girls could titillate the Czar – a verb whose meaning I understood but whose derivation I mistook. These views perturbed me because I was fond of the Nutcracker Suite, and my father thought highly of Wagner, bits of which thrilled me to the core.

4. BOWKER’S BUS

As with most MGS boys who lived at a distance from the school, getting there was part of our education. Many travelled long distances every day. Charlie Dover came from Southport, and others from Northwich, Macclesfield, New Mills, Oldham, Rochdale, Bolton, Chorley. All the towns round Manchester sent a daily quota. For my first three years I came in from Worsley and travelled on Bowker’s bus which went from outside the Court House directly to school. Most other travellers had to make their way from the city stations to Albert Square or Piccadilly and there catch a tram to Rusholme. Being a Bowker’s boy put me in touch with many opinions about the school. Gossip about masters passed pretty freely amongst the travellers and in good time I learnt about the madness and the badness of the tyrants I would shortly be subject to. Thus, while they were still only names, I knew about Billy Hulme’s spoons, Killer Maugham’s run-up with his gymshoe from the other side of the corridor.

The only other Prep boys on the bus were Caddy and McElvie, both in Prep 2. They’d been warned about me as someone it was their duty to look after, but I became a protégé, then a friend, not only while we were creatures enduring a common bondage, but outside school as well. At first they looked after me in a paternal way, sharing their sweets, which were rationed, and ‘bringing me on’ with what they discovered about sex and football, as their minds were broadened. They referred to me as ‘Young un,’ which was a comforting change from the formal ‘Davidson’, used by everyone else. As the term went on we formed a small defensive group on the bus and became prepared to stick up for what we felt were our rights.

Bowker’s was an Institution and to go on it was an education in itself. Driven by the eponymous Mr Bowker, it was an ancient charabanc which seemed to have run boys to MGS ever since the Owl flew from the city’s heart to fairer, greener Rusholme. Starting from Worsley at half-past eight, Bowker’s wound its way through the south-western suburbs of Manchester, picking up boys as it went. It trudged through Monton and Eccles and Pendleton to Salford, by which time it was uncomfortably full, the seats occupied by disgruntled scholars and the aisle packed with small boys. The return journey, which was generally much more cheerful, started from Birch Hall Lane at ten to four.

Before I’d even started school, I was put in the care of my mother’s friend’s son, Tom. ‘Tom will look after you,’ the mothers said. But Tom was diffident about the relationship, and I never warmed to him. On my first journey he nodded to me as a distant acquaintance, and thenceforth left me alone. In the third row down, left-hand side sat Mr Tenen, who taught History, and was undoubtedly Master of the bus. Large and solid, behind his Manchester Guardian, he could be marked immediately by his trilby hat in a sea of caps. On my first journey I settled into a window seat thinking it was mine. Two miles down the road a wave of dark blue and light blue caps flooded in and I was washed out of my window seat by a thug, who gestured with his thumb. ‘Mine!’ he said. ‘Out!’ I looked in vain for help from my carer, but he was studiously busy and he’d already discouraged me from sitting next to him. I found somewhere else, only to be ejected at the next stop, and so it went, until the aisle between the seats was full of small, disconsolate boys. Apart from some seats, which were the subject of private disputes, every place in the bus might as well have been labelled and the only permanent unclaimed position was next to Authority. This was sooner or later uneasily occupied by one of the dispossessed, pushed into the aisle. Mr Tenen was affable but not inclined to chat, ‘What form are you in, boy?’ he would say as you edged into the place beside him. When you made your halting reply he would make some remark about your form master – like, ‘He’s a terror. You’ll have to watch yourself,’ – then return to his paper.

Memories of those morning journeys remain with me still: the jolting of the bus, the line of dark blue raincoats carefully buttoned up, each with its satchel on the back. Down the middle of the bus the file of small boys swayed and bumped as progress was interrupted by road junctions and traffic lights. With little to hold onto but the handles on the backs of the seats, we all fell over like a row of dominoes when the bus stopped suddenly, and the end of the file landed on the knees of those on the back seat, where the privileged sat. As I write, I feel again the chilling disdain with which our elder fellows treated us, and sense the utter desolation of being a small, helpless entity wholly subject to the will of others. The last stop to collect passengers was at Monton Green. After that, we settled down into readers and chatterers and late-homework-finishers. Some would be hunched over their schoolbags seemingly in a trance, others studiously conning homework, one scribbling lines as though his life depended upon it.

As our journey progressed, I found it a relief to get out of dingy Salford and into Manchester proper. After we crossed the Irwell and went up Quay Street it was clear we were into a different kind of place. The Opera House was a pale baroque wonder amongst the five-storey offices. The posters without proclaimed the wonders within. The Christmas before I’d joined Prep 1, I’d been taken there to see Peter Pan which I still remembered vividly. For two hours I was part of a world where horror and humour, dream and reality were mixed up in a story about fairies. Was it right that you only had to believe in something for it to be true? I wasn’t prepared to believe I could fly, but Captain Hook and the crocodile were as real as the alarm clock which tick-tocked at my bedside. Smee, the sly, punctilious Smee, who “stabbed without offence”, haunted my dreams along with visions of the bombed and the dispossessed.

Along Deansgate, where we dodged the trams, the bustle on the pavements and the tall buildings on either side produced an authentic sense of being in a real city. There was John Rylands library on one side, a different kind of Gothic from Pendleton Hospital, which itself was different from the angular glory of Manchester Town Hall. On the other side, beneath a formidable massif of offices, I was puzzled by a long arcade of ten or a dozen identical windows, each bearing the name HEYWOOD, with, ELECTRICAL WHOLESALER in smaller letters underneath. What, I wondered was a ‘wholesaler’ and what were ‘electrical goods’? Why did he need so many shops to sell them from? Then we were at Knott Lane and up to the Oxford Street traffic lights with the Palace Theatre almost opposite the Tatler Cinema, where, in times to come, I spent many afternoons watching Bugs Bunny and Flash Gordon.

The centre of Manchester was always interesting. The playbills at The Palace advertised comedians we knew from the radio: Rob Wilton, Charlie MacArthy, the ventriloquist’s dummy who strangely became famous on the air, and singers like Anne Ziegler and Webster Booth. The Christmas Pantomimes starred Hetty King in Puss in Boots or Frank Randle in Jack and the Beanstalk