Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

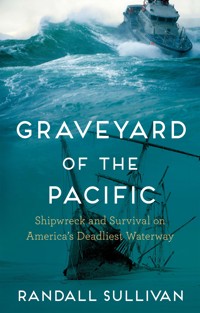

Off the coast of Oregon, the Columbia River flows into the Pacific Ocean and forms the Columbia River Bar: a watery collision so turbulent and deadly that it's nicknamed the Graveyard of the Pacific. Two thousand ships have been wrecked on the bar since the first European ship dared to try to cross it in the late 18th century. Since then, the commercial importance of the Columbia River has only grown, and the bar remains a site of shipwrecks and dramatic rescues as well as power struggles between small fishermen, powerful shipowners, local communities, the Coast Guard and the Columbia River Bar Pilots - a small group of highly skilled navigators. When Randall Sullivan and a friend set out to cross the bar in a two-man kayak, they're met with scepticism and concern. But on a clear day in July 2021, when the tides and weather seem right, they embark. As they plunge through the currents that have taken so many lives, Randall commemorates the brave sailors that made the crossing before him - including his own abusive father - and reflects on toxic masculinity, fatherhood and what drives men to extremes.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 400

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Randall Sullivan

Dead Wrong

The Curse of Oak Island

Untouchable

The Miracle Detective

LAbyrinth

The Price of Experience

First published in the United States of America in 2023 by Grove Atlantic

First published in Great Britain in 2023 by Grove Press UK,

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

Copyright © Randall Sullivan, 2023

Maps © Martin Lubikowski, ML Design, London

The moral right of Randall Sullivan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Photo credits are as follows: Photos 2.2, 4.2, 9.1: Wikimedia Commons; Photo 3.1: Greg Vaughn / Alamy Stock Photo; Photo 3.2: Wikimedia Commons via Clatsop County Historical Society; Photo 4.1: PD-US; Photos 5.1, 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 14.1: Courtesy of author; Photo 5.2: Courtesy of US Coast Guard Cape Disappointment; Photo 7.1: Courtesy of Nick Chipchase; Photos 8.1, 8.2: Washington State Digital Archives; Photo 9.2: Xander Fulton via Flickr; Photo 10.1: Photo Kiser Photo Co. photographs, 1901-1999; bulk: 1901-1927; Org. Lot 140; OrHi 56563, Photo 10.2: Flickr © 2011 Kay Gaensler; Photos 7.2, 11.1, 11.2, 12.2: Columbia River Maritime Museum; Photo 12.1: Columbia River Maritime Museum / Lawrence Barber; Photos 13.1, 13.2, 13.3, 13.4: Port of Portland YouTube @portofportland; Photos 15.1, 15.2, 16.1, 16.2: Courtesy of the US Coast Guard Auxiliary; Photos 13.5, 14.2: Columbia River Bar Pilots Association.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN 978 1 80471 036 4

E-book ISBN 978 1 80471 037 1

Printed in Great Britain

Grove Press UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

For Delores,

who calls me back to shore like no other.

Imagine an enormous row of waves breaking for a distance of three leagues from Cape Disappointment to Point Adams, and forming kind of a sandy crescent about 1500 meters long at the river’s mouth. The sea water, whipped in by the wind towards the river mouth, encountered the river water on this enormous sand bar, producing frightful impact; the noise is so loud that you can hear it several leagues away, and the mountainous waves—resulting from the meeting of two opposing currents—reach a height of sixty feet . . .

Expert English, American, and other navigators have asserted that there is no worse sea lane than this in the known world . . .

Its currents, its rip tides, its storms, its sudden wind changes make it exceptionally dangerous, and the enormous bar does nothing to lessen the danger, especially in bad weather.

Louis S. Rossi,

Six Years on the West Coast of America, 1856–1862

THE GREAT RIVER OF THE WEST was born from violence, from fire, and from ice. Fire came first. More than 250 million years ago, when most of the landmass of Earth was contained within the supercontinent Pangea, superheated liquefied rock, magma, burned a three-pronged rift through the crust and began the tectonic separation of North America, Europe, and Africa. As the new continents drifted apart, somewhere between one hundred million and ninety million years ago, the movement of plates floating atop a fiery mantle pushed long chains of active volcanoes hard against the upper left edge of North America, a scorching fusion that created what is now the Pacific Northwest.

The future basin of the Great River was surrounded then by the continuously bubbling, spewing, spreading eruptions of the young mountains that shaped the original configuration of a track flowing out of what is now Canada toward the Pacific Ocean. It was the molten lava that pulled the moisture out of the Earth’s interior and left water on the planet’s surface as it cooled. An ancestral version of the river was soon descending from a long, sunken fault line that would become the Rocky Mountain Trench.

The Rockies themselves rose as massive upwelling explosions between eighty and fifty-five million years ago, and off their western flanks sent huge flaming flows of basalt lava south to push out an inland sea and shape the path of the still-forming Great River beneath it. The Cascade Mountains are much younger than the Rockies—they did not uplift out of the Earth’s mantle until five to four million years ago—but they were also enormous fulminations that further seared and shifted the region’s topography, helping to define the outline of an immense waterway.

Then, about thirty-three thousand years ago, North America’s volcanic fires were overtaken by a rapid expansion of ice spreading south, caused, scientists believe, by a shift in the Earth’s orbit around the sun. Five thousand years later, much of North America was under two enormous ice sheets. The one to the west, the Cordilleran, covered at its maximum nearly two million square miles of land, stretching from Alaska to Montana, and may have reached as far south as the northeast corner of Oregon.

That ice is what put the finishing touches on the formation of the Great River. The gouging of glaciers moving south and west did a good bit of the work, but it was the melting of the ice that had the greater effect. Around nineteen thousand years ago, when the glaciers began to once again retreat, a gigantic frozen wall, an ice dam, embanked an enormous body of fresh water that geologists call Glacial Lake Missoula. The gargantuan pond was two thousand feet deep then and about the size of today’s Lake Ontario. On at least forty occasions between nineteen and thirteen thousand years ago, the ice dam that held back Lake Missoula failed. The resulting floods were epic on a scale that defies human imagination. Each one unleashed more water than was in all of the Earth’s rivers combined, scouring its way through mountain ranges to inundate an area of sixteen thousand square miles to a depth of up to several hundred feet. In the center of the flood path was what would become the bed of the Great River. When the waters receded, the ultimate course of that river, and of its connection to a vast system of tributaries, was left behind.

Where the river began then was where it does now, spilling out of the remnant of a smaller glacial lake that had been swept up into the Lake Missoula floods. Situated today in southwestern Canada, the lake bears the name of the river it has spawned, Columbia.

Given the underlying law of rivers—water runs downhill—it’s surprising that the headwaters of the Columbia River are at a modest elevation of 2,690 feet. The Columbia’s long descent to the ocean, though, is not only expanded but also hastened by the rivers, creeks, and streams pouring down into it from the mountains on both sides.

Curiously—one is tempted to say, perversely—a river that for most of its more than twelve-hundred-mile length flows south and west begins by heading north for 218 miles in a detour around the Selkirk Mountains, taking in, among other lesser tributaries, the icy Spillimacheen River that plunges down from the eastern edge of Glacier National Park, dropping nearly six thousand feet in elevation in fifty miles before pouring out of the rocks like a long waterfall into the Columbia. Then, at what has become known as the Big Bend, just above the northern reach of the Selkirk Range, the river makes a dramatic reversal of course, turning sharply almost due south as it drops through Canyon Hot Springs.

Soon after, sixty miles above what is now the United States border, and still headed south, the Columbia is joined by its first truly major tributary, the Kootenay River, 485 miles long and draining an area of more than 50,000 square miles, dropping 6,600 feet in elevation from its headwaters on the northeast side of the Beaverfoot Range before it merges with the greater river. Flowing through and alongside steep mountains, the Kootenay collects the waters of its own sizeable tributaries, including the 128-mile-long Duncan, before emptying them into the flow of the steadily swelling Columbia.

A thousand years ago, two large tribes lived in this area, on each side of what they called, in different tongues, Big River. To the west were the Sinixt, the Lake People, inhabitants of the region for ten thousand years, whose dwellings during the winter months were half-buried houses. East of the Columbia, the Kootenai nation used an “isolate language”—one that had no relation whatsoever to those spoken by neighboring tribes; some scholars contend that their ancestors migrated from what is today the Michigan side of Lake Superior. The Kootenai traveled the rivers in canoes as original as their language, made of dug-out cedar logs with pine bark on the bottom and birch bark at the gunwales, remarkable mainly for the way both ends were bent sharply inward, the same on one end as on the other, so that when spinning in rapids there was no definite front or back.

South of what is now the border between Canada and the United States, the Columbia is joined by the Pend Oreille and the Spokane, rivers that between them drain nearly 34,000 square miles stretching across Montana, Idaho, and Washington. The Big River continues west until its confluence with the 115-mile-long Okanogan River, then turns south again on a stark but achingly beautiful granite plateau where rattlesnakes live among sagebrush, prickly pear cactus, and tumbleweed.

Passing through the arid but fertile plain of central Washington State, the Columbia absorbs yet another large tributary, the 214-milelong Yakima River, one more part of the Big River’s system that bears the name of the people who lived there before the arrival of Europeans.

Nearly forty miles south of the Yakima, the Columbia’s largest tributary, the Snake, a great river in its own right, adds the waters it has collected from six US states and a drainage area of more than one hundred thousand square miles. The Snake is smooth and wide where it enters the Columbia in today’s southeastern Washington, but for most of the 1,078 miles behind it the river is as dramatic as any on the continent. Beginning at the confluence of three tiny streams in what is now the Wyoming section of Yellowstone National Park, flowing west and south into Jackson Hole, through the most spectacularly lovely mountain range in America, the Tetons, the Snake crosses plains and deserts as it turns up, then down, then up again across the entire width of Idaho before entering what is possibly the most impassable section of river on the planet, Hells Canyon, a 7,993-foot gorge (North America’s deepest) forming what is today the eastern border of Oregon, which separates it from Idaho and Washington.

The people most associated with the Snake River are the Nez Perce. Powerful in war and trade, the Nez Perce nation lived in seventy separate villages, inhabited a territory of seventeen million acres, and networked with other tribes all the way from the Pacific shores of present-day Oregon and Washington to the high plains of Montana to the Great Basin part of Nevada.

Nearly a mile wide by now, the Columbia moves more slowly west through the lava plateau on both sides of it, taking in, among other rivers, the 252-mile Deschutes and the 284-mile John Day. The Great River narrows and accelerates as it enters the gloriously lovely Columbia Gorge, a four-thousand-foot deep, eighty-mile-long canyon with what is now Oregon on the south shore and Washington on the north. As the gorge deepens, the river’s run passes from grasslands marked by widely spaced lodgepole and ponderosa pines into a thick rainforest of firs and maples that tower on the cliff face above. The deepest cut of the gorge is a wind tunnel that propagates howling snow and ice storms during winter months. Waterfalls abound on both sides of the river in the gorge, and one of them, Celilo, was not only a prime fish-catching spot but the main trading station between the upriver tribes that spoke the Sehaptian tongue and the peoples downriver that spoke the Chinookan language.

Passing through the gorge, the river is headed to where its truly great wealth lies. The Columbia’s size is of course part of what makes it a great river. Only the Missouri/Mississippi system exceeds it in annual runoff, and there are years when the Columbia’s flow is greater. Both of America’s major river systems work off the “tilt” of the Continental Divide, one running toward the Pacific Ocean off the divide’s western flank, the other running off the eastern flank into the Gulf of Mexico. The Columbia is unique among all rivers of the world, though, in the combination of its close proximity to the ocean and the tall mountain ranges that feed it all along the way there. Fifty miles west of the Columbia Gorge, the Big River’s second-largest tributary, the Willamette, each spring carries the snowmelt from the Cascade Range north through a valley where volcanoes and glacial floods deposited some of the richest soil on the planet, then pours it into the Columbia, also fed largely by snowmelt from the mountain ranges it has passed through and alongside. Thirty-two other tributaries feed the Big River with rainwater in the ninety miles between the Willamette and the Pacific Ocean, and by late May and early June the flow of the lower Columbia becomes truly stupendous, carrying up to 1.2 million cubic feet of water per second at its mouth, nearly five times its average discharge. Two hundred years ago, all of that free-flowing cold water in late spring provided the perfect spawning grounds for anadromous fish, those that live in the ocean but lay their eggs in fresh water.

Before fourteen dams were built on the river, the Columbia’s salmon runs exceeded any on Earth. Four million of the big fish would spawn in the river each spring. What became known as Chinook salmon grew to weigh more than one hundred pounds in those days, and the Columbia was so thick with them that in the nineteenth century more than one man would report being tempted to try to walk across the river on their backs. Not only delicious but immensely rich in protein and omega-3 fatty acids, they were a primary food source for the peoples who lived along the Columbia for hundreds of miles to the north and east. But on the lower Columbia the salmon runs were far beyond abundant, and they were a good part of what made the tribal villages there the richest, in nearly every material sense, on the planet. The plentitude of food they enjoyed was unimaginable to nearly everyone else on Earth. Apart from the staggering salmon runs, the Columbia was filled with uncountable sturgeon, steelhead, and shad. The evergreen forests alongside teemed with deer, bear, and elk. Blackberries, huckleberries, and salmonberries were profuse in late summer. The result of such an extravagant supply of sustenance was a settled people who lived not by the egalitarian principles of nomadic inland tribes like the Shoshone, Sioux, and Blackfoot, but who were nearly as hierarchical as Europeans.

Chiefs of Northwest Pacific Coast tribes dwelled in fur-upholstered cedar longhouses, elaborately carved, that could accommodate as many as seven hundred people. Tribal headmen regularly staged “potlatch” ceremonies, essentially giveaway competitions that ended only when one chief had no more lavish gifts to bestow upon another, and so surrendered his prestige. Some chiefs went so far as to destroy what they had been given, so as to demonstrate how little value they placed on such trifles. Common tribal members lived far better than the average citizen in London or Paris, and in each village most of the hard labor was done by slaves captured in battle.

The Chinookan tribe at the mouth of the Columbia, the Clatsop, enjoyed bounties beyond even those of the wealthy tribes upriver. Where it entered the ocean, the Big River’s bays and estuaries, along with the ocean beaches just beyond, provided endless crabs, mussels, and clams. Halibut were easily caught right outside the river’s mouth, while seals and whales could be taken within sight of land.

For thousands of years the Clatsop lived with a security that only island peoples knew so well. To the east and north were other Chinookan tribes that only infrequently contested the Clatsop’s territory. To the south, the Salish and Klamath nations were trading partners more than rivals. And the Clatsop certainly had nothing to fear from the west, where the mouth of what they called Wimahl (again “Big River”) drove its way into the ocean.

The Clatsop couldn’t know there was nothing equal to this encounter of current and tide on the continent—or on the entire planet, for that matter—only that there was nothing like it in the world where they lived. The collision of these two immense forces, the Pacific Ocean and the largest river of the Western Hemisphere that drains into it, created a spectacle that was stupendous even to a people that had been living next to it for a thousand years. On many days, the line of breakers where the river met the ocean stretched five miles across, and the roar was thunderous. During winter storms, the waves at the outside of the river’s mouth would reach the height of ten men. The Clatsop on occasion dared to cross out into the ocean from the river in immense, sixty-five-foot-long canoes that could carry more than fifty paddlers. This they did only when conditions were perfect, however, and only they knew when perfect conditions existed. The notion of some other tribe coming in off the ocean into the river through the maelstrom that would almost certainly greet them was unthinkable.

Until it happened.

The Clatsop passed down the story like this: An old woman living in the village closest to where the river entered the ocean, Ne-ahk-stow, was walking along the beach toward the giant sand spit at the end of the southern shore when she saw something strange and frightening approaching out of the sea. At first she thought it might be some kind of unknown whale, the story went, then saw that there were two trees growing out of it. The outside of the strange thing was covered with shiny metal, and ropes were tied all over the trees. As it came closer, the old woman saw that a creature that looked like a bear but had a human face, only one with hair covering most of it, was standing between the two trees. She hurried home in great fear and told the other villagers what she had seen. The warriors sprinted up the beach in the direction the old woman pointed, armed with bows and arrows, and found that the strange thing with trees growing out of it had come ashore. Now there were two of the bear-men standing between the trees. The warriors watched from the forest at the edge of the beach as the two bear-men carried a kettle ashore, lit a fire under it, and threw dried corn inside. The crackling, startling result so intrigued the warriors that they came out of the trees. The bear-men offered them some of the popped corn, then signaled that they themselves needed water. The village chief sent men to get them water while he studied the strange thing, which he decided was an enormous canoe that for some reason had two trees driven into it. The chief then inspected the hairy-faced creatures and, after examining their hands, decided that they were in fact men. While the bear-men slaked their thirst, a young warrior climbed up the side of the great canoe and looked down onto its deck, where he saw not only many boxes and strings of buttons nearly as long as the beach, but also, most excitingly, an abundance of metals: iron, copper, and brass. To take that metal, and to hold the bear-men captive, the chief ordered that the great canoe be burned.

Word of this event spread, and soon tribes from all over the region sent warriors to take a look at the “Thlehonnipts,” as they were called, “those who drifted ashore.” Groups of Quinaults, of Chehalis, of Willapas, of Cowlitz, even of the far-off Klickitat arrived, and all laid claim to the Thlehonnipts. It nearly came to war, until the Clatsop chief agreed to surrender one of the two Spanish sailors, but he insisted upon keeping the Thlehonnipt he most prized, the one who had shown he knew how to make knives and hatchets from pieces of iron. Konapee, or “Iron-Maker,” the Clatsop had named him.

Konapee became a highly valued member of the tribe and lived with them for the rest of his life. The Clatsop did not expect that other such men would be drifting ashore, and none did for many years. Then, though, they began to arrive one after the other. The forbidding barrier of breakers and shoals at the mouth of the river had frightened some away, and many who did try to pass through disappeared beneath the waves. But enough of the Thlehonnipts made it across to encourage others, and within a span of less than fifty years a Clatsop way of life that had gone on for century after century vanished forever.

No future apologies or reparations were going to change what had happened. The best that could be hoped for was that those who drifted ashore would have stories worth hearing.

CHAPTER ONE

Friday, July 16, 2021

AS WE LIFTED OUR BOATS off the trailer, the sky was low and gray all the way to the horizon, with only a faint spot of lightening in the south to suggest that the sun was there at all. The air was filled with drizzle and mist, precipitation and evaporation, falling and rising. Lowering my end of the main hull onto a damp patch of mossy grass, I felt a slightly claustrophobic sensation of not just the weather closing in around me but the whole world with it. The scene was so far from what I’d imagined, from the picture in my mind of luminous blue overhead and vivid white caps marking our distant goal, that for the first time I felt doubt slipping in through the cracks in my resolve, and wondered about continuing forward.

FOR MONTHS NOW, MY FRIEND Ray Thomas and I had been talking about the RIGHT DAY to cross the Columbia River Bar. The words had been in quotation marks the first few times we’d used them, but grew into all caps as the concept loomed larger and larger in our thoughts. The venture we had in mind would only make sense, we kept reminding each other, if we found the Right Day.

When I’d first spoken to Ray about “the right day” back in April, I’d been quoting Bruce Jones, who, along with occupying the office of mayor of Astoria, Oregon, served as deputy director of the Columbia River Maritime Museum. In the email in which he introduced himself and suggested we meet at the museum, Mayor Jones had attached a photograph of the astounding turbulence a person might encounter at the place where one of the world’s largest, most powerful, and fastest-moving watercourses spills into the Pacific Ocean. Actually, this intersection of river and sea is more of a slam than a spill—“like two giant hammers pounding into each other,” as the head of the Columbia River Bar Pilots Association described it to the New York Times back in 1988.

I studied the image Jones had sent—lashing towers of white water swamping the massive wall of mounded stones that formed the Columbia Bar’s North Jetty—and felt a contraction run through me from throat to sphincter. He had taken the photograph in “my previous life,” Jones explained in his email, while flying the Bar Pilots Association’s Seahawk helicopter, his primary job to drop pilots on inbound ships five miles outside the entrance to the bar.

The photograph, taken during a November squall, “doesn’t do justice to the violence of the seas and wind” he saw that day, Jones had written. Those words would have seemed even more ominous if I’d known when I read them what an understated man Bruce Jones is. There was one word in his brief email that gave me comfort, though, and it was “November.” While I realized it was impossible to ever be entirely certain about the weather on the Columbia Bar, because conditions were known to deteriorate dramatically in a span of minutes during any season of the year, I knew Ray and I weren’t going to be attempting any crossing of the bar in either water or air as cold as November’s.

Based on his email, and in particular on the photograph he’d attached, I had expected Jones to be somewhere between aghast and dismissive when I told him at the beginning of our meeting in the museum’s conference room that, as part of a book I was researching, my friend and I wanted to cross the Columbia Bar in what was essentially a sail kayak, a Hobie Adventure Island trimaran. Instead of scorning the idea, though, Jones sat silent for a few moments, considering, then told me it was “doable” if we chose the right day.

A little later, Jones asked if my friend was my age. He was, I answered. Jones knew from an article about me that had been published recently on the front page of the Daily Astorian that I would turn seventy on my next birthday, in December. Ray would turn seventy himself four days after I did. Jones saw, I think, that I was in good shape for a man my age. Ray was even more fit, if less strong. Jones made no comment about the advisability of senior citizens, no matter how fit or strong, challenging the Columbia Bar in a nonmotorized light craft, and I appreciated that.

Bruce was a sturdy but not imposing man with gentle eyes and a bookish manner. I would have more likely made him for a professor at a small private college who hit the gym several times a week than for a helicopter pilot who’d made a career of flying in terrifying conditions. Even after our meeting at the museum, I wouldn’t learn for another week what a truly formidable fellow he was, a man whose accomplishments included commanding all and performing many of the air rescues in New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina. I should have seen him more clearly, I think now. And also, I should have shown more gratitude when he offered me the museum’s resources, including its library, which, although operated by volunteers, houses by far the best-documented history that exists of the Columbia River in general and of the bar in particular.

At the end of our meeting, Jones permitted me to roam freely through the museum, where the most arresting display was a large illuminated map of the bar highlighting two hundred of the more than two thousand shipwrecks that have happened there during the past couple of centuries. An estimated twelve hundred people, nearly all men, have died in those wrecks, though this estimate is rough, given that some of the oldest records state simply that “the entire crew” was lost. THE GRAVEYARD OF THE PACIFIC, read the heading on the display; it was the sobriquet seamen had bestowed on the Columbia Bar more than a century earlier.

I had known since I was a boy that the Columbia River Bar was generally regarded as the most dangerous entrance to a commercial waterway on the planet. It has been described many times as the world’s most dangerous bar to cross, period. One of those who said this was my father, who was a merchant marine when I was born and had by age twenty-five traveled to virtually every corner of the earth. The single most frightening experience he ever had aboard a ship, my father said, came the first time he entered the Columbia River Bar. The freighter he was aboard was about to run aground on a hidden sandbar that had appeared suddenly out of the fog off the port side of the bow, he recalled. Only a brilliant maneuver by the captain that bounced the ship off a smaller sandbar on the starboard side and spun it slightly had saved him and the others aboard, he said. My father was a man who almost never showed fear, or any other emotion that betrayed vulnerability, but I could hear the resonance of panic in his voice then, describing an experience he’d had twenty years earlier.

NO ONE OUTSIDE THE BAR PILOTS’ association knew the perils of the Columbia River Bar better than Tom Molloy, the commanding officer at the United States Coast Guard’s National Motor Lifeboat Rescue School. The Coast Guard’s main high seas rescue academy was located at Cape Disappointment, on the Washington State side of the Columbia’s mouth, because, as Chief Warrant Officer 3 Molloy told me, “we figure that the best place to learn this stuff is in the most challenging environment in the country.”

I liked Molloy a lot within a few minutes of meeting him. The same word that had come into my mind while talking with Bruce Jones occurred to me while getting to know Tom: “solid.” Only in Molloy’s case this word had a more distinctly physical aspect. Molloy was not a tall man—five nine, I’d reckon—but with a pair of shoulders on him that easily would have filled out a size 48 suit jacket. He had been built up, I would learn, from a life spent largely on the water. Having grown up as a surfer on the Atlantic coast of Florida, Molloy had joined the Coast Guard mainly as a way to stay close to the sea. Even now he kept a private surf spot in a cove hidden by a spill of rocks on the west side of the rescue school and the adjacent Coast Guard base. “I go out whenever I get the opportunity,” he told me with a grin that made me love him. Molloy was in his early forties, but there was something of the sunburnt boy about him, perpetually at play in the fields of the Lord. Yet he must take his duties seriously, I thought, or otherwise he wouldn’t occupy the position that he did.

I knew that was true when I observed the respect Molloy commanded from the young men and women he was training, evident in their admiring eyes as they saluted him passing them while showing me around the rescue school. Along with a rank that made him one of the more versatile members of the US Armed Forces, Molloy had been awarded what is probably the most coveted title in the Coast Guard, the “Surfman Badge,” conferred only upon coxswains who have qualified to operate boats in the “heavy surf” that is encountered regularly on the Columbia Bar. The surfman’s motto was: “The book says you’ve got to go out, but it doesn’t say a word about coming back.”

Molloy had bright eyes and a broad, open face. Perhaps the most telling thing I learned about him during the time I spent with Tom was that the tattoo on the third finger of his left hand was a replacement for the wedding ring he’d lost during a Coast Guard operation. He’d had the image of that ring inked onto his finger, made it literally part of his flesh, not simply as a form of apology to his wife but in order to demonstrate to her that his commitment was absolute.

I was pretty sure that Tom Molloy was what my friend Ray would have described as “one tough boy,” but there was nothing cocky or pugnacious about him. The man had the same sort of quiet confidence that I had recognized in his friend Bruce Jones, and there was something uplifting about meeting the two of them back-to-back, a confirmation of what I wanted to believe about the quality of the men who held sway on the Columbia Bar. My father, whom I grew up hearing described by the longshoremen working under him as the toughest man on the West Coast waterfront, might have had that same quality, I felt, if he hadn’t been so tortured inside and so prone to meanness.

My confidence was buoyed when Molloy agreed with Bruce Jones that crossing the bar in a trimaran could be done. And just like Jones, he said it was all about choosing the right day. Actually, “the right day at the right time of day” was what Tom said. I recalled that Bruce Jones had told me that finding a day in the second half of July or the first half of August was advisable, because both the air and the water would be warmer than at other times of the year. Molloy again agreed, but added, “Even in August the weather on the bar can turn nasty in no time. Boats go down and people drown out there in the summertime, too.”

There were three awesome forces to contend with on the bar, Molloy reminded me: tide, current, and wind. All had to be accounted for in any calculation of the risk involved in being out there.

I had understood even before my meeting with Bruce Jones that Ray and I did not want to be out on the bar in an outgoing tide, because the greatest danger to us, in a nonmotorized craft, was being capsized and swept out to sea. Jones’s colleague Jeff Smith, the museum’s curator, had suggested setting out on a slack tide, in the interval between the ebb and flood tides. Molloy disagreed slightly: he believed it would be best for us to launch about an hour before low tide. “That last bit of ebb tide will help push you out into the river, you can get going during slack tide, then use the flood tide to hold you in until you get back on land,” Molloy said. We wanted to be sure we had as many hours of rising tide as possible to work with, he explained, “because you never know what kind of complications might come up. Believe me, if your boat capsizes you want to be in the water with the tide coming in. Much better chance of making it to shore, or being located and rescued should the need arise.”

RAY AND I HAD MANAGED to get together for three practice sessions in the trimaran, each several hours long. Our first was on the Willamette River, which is the arterial center of Portland, Oregon. Ray kept seven boats of various sizes—the largest being a Kenner Suwanee houseboat equipped with a working woodstove we’d enjoyed on a fair few winter evenings—at Portland’s gem of a downtown marina, Riverplace.

Ray had gotten rich about a dozen years earlier, when he’d finally collected his share of attorney fees from a lawsuit against the cigarette manufacturer Philip Morris that went all the way to the United States Supreme Court. I’d remarked several times that Ray was the only person I’d ever known who seemed to have been made happier by becoming wealthy, but I wasn’t sure I meant it. He did seem to be having more fun, though, and definitely owned more expensive toys to have fun with. Crossing the bar on his Honda jet skis would have been many times easier than in the trimaran, Ray had pointed out, but I didn’t want it to be easy, and he understood that.

When I’d first proposed this undertaking, I could see Ray calculating not only the factors of risk and reward but also just how much he trusted me. I’d explained to him that part of what the book I wanted to write would be about was the effects on us both of having grown up amid so much violence, a great deal of it inflicted on us by our fathers. I felt it had a lot to do with why we’d each been driven to do difficult and dangerous things, as a way of demonstrating our ability to cope with and even master those difficulties and dangers.

Ray’s enthusiasm appeared to waver. He was wary of any encapsulation of him I might attempt. “I’m not ever trying to prove anything to anyone,” he told me.

The right thing to do as his friend, I decided, was accept this. “Me neither,” I told Ray. “Except maybe to myself.”

“Not even to myself,” Ray said. “I do what I do because I want to, period.”

If you say so, Ray, I thought this time, but just nodded.

By the time we first sat down together in the trimaran, me in the front position, him in the rear, on a glimmering May afternoon, I had accepted that Ray felt a need to test me. I understood already that his trimaran was a unique vessel. A two-seat kayak, nineteen feet long by just a little more than two feet wide, was the centerpiece, but Hobie had equipped the boat with assorted special features, including a pair of collapsible outriggers (called by their Polynesian name, “amas”) that provided an extraordinary enhancement of stability on the water, even though each was only about six inches wide. In addition to paddles that were generally used only in shallow water or tight spaces, the trimaran provided two superior methods of moving across the water’s surface: a removable single mast and sail was one; the other was Hobie’s marvelous Mirage Drive system—two “kick-up fins” attached to pedals that can nearly double the boat’s speed even when the sail is full. What Ray wanted me to prove was that I could pedal in the trimaran for up to three hours at a stretch. The Mirage Drive might be our main form of propulsion out on the Columbia Bar, depending upon the wind, and especially given that we would be pushing against a flood tide for most of the trip.

Still, I felt Ray had reminded me one time too many that for more than twenty years he’d been leading a weekly bicycle ride into the steep hills above Northwest Portland in which the other participants were lawyers less than half his age. My only bike was a beach cruiser that I rode eight or nine times every summer. I needed to demonstrate that I could “keep up,” Ray said, for him to feel confident going forward.

In addition to testing me, Ray also wanted me to understand that he was our captain. It was his boat, one he’d sailed off both the East and West Coasts of the country (and on the Mississippi River as well), in a variety of challenging conditions. But the way he barked orders once we were out on the water began to bring back some unpleasant memories from my childhood, and finally I told him to dial it down. “You rebel against every form of authority,” Ray said. “That concerns me.”

I was able to laugh and keep on pedaling.

The Willamette is a major river, the largest “in” the state, given that the Snake and Columbia run along Oregon’s eastern and northern borders. Sailing the Willamette, though, was like boating on a small lake compared to how it would be on the Columbia Bar. When we returned to the boat launch at Willamette Park after a pleasant if exhausting excursion, Ray was cheery, telling our six-foot-nine-inch training advisor, Kenny Smith, who lived with his girlfriend, Candy, aboard the biggest boat on the Willamette, a sixty-eight-footer he’d bought from a professional hockey player and hauled down from Canada, that I had “performed excellently” and really surprised him by pedaling steadily for two and a half hours.

Positions, both literal and figurative, began to shift between Ray and me during our two practice sessions in the trimaran on the Columbia. We set off on the first of these from the boat launch in Hammond, a community spread along the westernmost reaches of Youngs Bay, a huge spread of choppy water created by the flow of the Youngs River into the Columbia close to the bigger river’s mouth. Hammond had been through several iterations. For centuries it was the village the Clatsop tribe called Ne-ahk-stow. Then, in 1899 it became New Astoria, a name I found pretty amusing when I first heard it. Astoria—“old Astoria,” so to speak—was less than six miles to the east. The “New” part made some sense, I supposed, given that Astoria itself is the oldest enduring American settlement west of the Rocky Mountains. Beginning with the winter of 1805–1806, when the Lewis and Clark Expedition waited in vain for a ship at a tiny log structure they called Fort Clatsop, just southwest of where the city stands today, Astoria has been one of the most storied towns in the entire United States. During the nineteenth century alone, Astoria transitioned from frontier trading outpost to crucial military installation to wide-open seaport, where tall ships crowded into its harbor while disembarked sailors swarmed the dozens of saloons, brothels, and card parlors ashore.

Hammond’s history is considerably more modest, even though its access to the mouth of the Columbia River had positioned it to be “the greatest harbor on the Pacific coast north of San Francisco,” according to an Oregonian article published in July of 1895. The name Hammond was given to the former New Astoria in 1903 by a man who promised to build a gigantic sawmill on the two thousand feet of waterfront he had purchased there. Instead, Andrew B. Hammond built his mill at Tongue Point, on the peninsula north of Astoria, and the town that bore his name languished. By 1991, Hammond had been absorbed into the town of Warrenton, but the community still identified as a distinct entity, and as good a place for a fisherman to live as existed on the West Coast.

Hammond’s most notable feature, for Ray and me, was its marina, which allowed one to put in off a launch that offered a remarkably close view of the Columbia River tumbling past in all its immense and astonishing power. The Hammond Boat Basin was not only literally the last place on the Oregon side where one could board a vessel before approaching the Columbia Bar, but the little marina’s channel was so short that even our trimaran passed out of it into the river after only a couple minutes of paddling and pedaling on the afternoon of May 21.

We knew already that the wind that day was steady at about twenty-two miles per hour, too intense for a bar crossing in a kayak, but neither of us was prepared for what that felt like on a span of the river where the Columbia’s mouth was only a little more than a mile to the west. The wind waves were three and four feet, not coming in sets at intervals of seven to nine seconds like on the ocean, but in an incessant and erratic chop that struck our boat from changing directions as current and tide thrashed against one another. I was in the front position again, and up there I felt more like a buckaroo than a sailor, being tossed not only from side to side but also fore and aft as we passed abruptly over peak and into trough and then onto peak again, and so forth, our heads soaked, gasping in awe. Our sail was full, and we were both pedaling, going at what was probably the trimaran’s max velocity, about seven miles per hour.

After a few moments of being shaken, I felt exhilaration rise in me, and I was grinning crazily, marveling at how well the Hobie absorbed the pounding it was taking, continuously oscillating back to equilibrium, no matter how tilted it was by the waves. We had headed out of the boat basin straight for the buoy that floated in the middle of the river, intent on crossing to the Washington side, a distance of nearly four miles. We got only as far as about a hundred yards from the buoy, though, when Ray, who had the rudder, turned us back to shore.

The wind and our front-to-back positions made explanation difficult, but when I turned to look at Ray, I was pretty certain I saw fear in his eyes. This was perfectly understandable under the circumstances, I knew, but I was disappointed that we hadn’t continued across the river. And I was surprised. I knew Ray as a risk-taker. He had long been unpopular among the wives of various friends and associates, mainly because they believed he was determined to put not only himself but also their husbands into life-threatening situations. It was a reputation that discomfited him even as he cultivated it.

Yet Ray had been circumspect from the first about the idea—my idea—of us crossing the bar in his trimaran, warning me more than once that it would have to be approached in stages that started with building trust that we could work as a team on the water, and then together studying the Columbia Bar in depth and at length before venturing onto it. That was fine. I was already committed to doing the research in order to write this book, and it seemed like an excellent idea for Ray and me to practice in the trimaran for some number of times before taking on the bar. To my growing concern, and even annoyance in a couple of cases, though, Ray had begun to remark that he wasn’t sure about this whole project, that he doubted I understood how dangerous it was, and that it didn’t mean nearly as much to him as it did to me.

That morning of our first practice session on the Columbia, Ray had equivocated again, informing me, “Grace told me this morning she doesn’t want to be planning my funeral in the near future.” Grace was Ray’s third ex-wife. They’d been divorced for more than twenty years but still traveled together. There had been a period of a few years when Ray had tried to convince himself, and me, among others, that he was capable of sustaining relationships with several women at once, all out in the open, on the up-and-up with each of them. I’d enjoyed more than a little acerbic humor at his expense as, one by one, they dumped his ass for such a delusional presumption. But he’d been in love with Grace all along. They were so cozy these days that they’d recently bought a house together. It was one of a number of houses owned by Grace, but Ray’s only real residence, other than the small apartment he maintained in the office building that housed his law practice.

Among our sorrowful bonds was that my life was at least as messy as Ray’s. I had three ex-wives also and was now married to my “fourth and final wife,” as I regularly described her. Like Ray’s relationship with Grace, this one was going to last, I knew, both because I loved Delores dearly and because I had run out of time and excuses. On our honeymoon in Ireland, my new wife took to telling the women she met in pubs that she had waited eighteen years to marry me. That was true, except for the eighteen months we spent apart when she got fed up with me and moved to North Carolina. The women in Ireland responded to whatever it was Delores told them about this with a depth of emotion that flabbergasted us both. Whole tables wept with joy. Irish women of all ages actually stood to cheer and applaud this tale of triumphant endurance, which in private Delores offered up to me as proof that she always got what she wanted, in the end.

Delores was no less apprehensive about the bar crossing than Grace, and had attempted to talk me out of it half a dozen times. She collected warnings from various neighbors in the small beach community where we lived, about fifteen miles south of Astoria, who wondered whether I had a death wish or was merely an idiot. When I told her there was no point, that I was determined to do this, that I needed